| Revision as of 20:16, 31 March 2010 editPaulista01 (talk | contribs)711 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:10, 1 April 2010 edit undoOpinoso (talk | contribs)7,395 edits Adding fact tags to conclusions that seem to be based on nothing. Moreover, one source claiming that 10% and another that 15% are of Italian descent doesn't seem to be a "contraditions" (only 5%)Next edit → | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

| ==Statistics== | ==Statistics== | ||

| The Brazilian Censuses do not ask questions about "ethnic origin", so there are no systematically comparable data about the impact of Italian immigration. Varied entities, mainly the Italian diplomatic system and commercial associations that promote bilateral commerce between Brazil and Italy, make claims about the figures of ''oriundi'' in Brazil, but none links to any actual survey. Also, if they are extrapolations of actual data on the number of immigrants, the calculations are not explained anywhere. | The Brazilian Censuses do not ask questions about "ethnic origin", so there are no systematically comparable data about the impact of Italian immigration{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} . Varied entities, mainly the Italian diplomatic system and commercial associations that promote bilateral commerce between Brazil and Italy {{Citation needed|date=March 2010}}, make claims about the figures of ''oriundi'' in Brazil, but none links to any actual survey. Also, if they are extrapolations of actual data on the number of immigrants, the calculations are not explained anywhere.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | ||

| On the other hand, in 1998, the IBGE, within its preparation for the 2000 Census, experimentally introduced a question about "origem" (ancestry) in its "Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego" (Monthly Employment Research), in order to test the viability of introducing that variable in the Census<ref>http://www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/pdf/origem.pdf p.3</ref> (the IBGE ended by deciding against the inclusion of questions about it in the Census). This research interviewed about 90,000 people in six metropolitan regions (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Recife) <ref>/www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/pdf/origem.pdf Note 3, p.3</ref>. To this day, it remains the only actual published survey about the immigrant origin of Brazilians. | On the other hand, in 1998, the IBGE, within its preparation for the 2000 Census, experimentally introduced a question about "origem" (ancestry) in its "Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego" (Monthly Employment Research), in order to test the viability of introducing that variable in the Census<ref>http://www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/pdf/origem.pdf p.3</ref> (the IBGE ended by deciding against the inclusion of questions about it in the Census). This research interviewed about 90,000 people in six metropolitan regions (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Recife) <ref>/www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/pdf/origem.pdf Note 3, p.3</ref>. To this day, it remains the only actual published survey about the immigrant origin of Brazilians.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | ||

| The results of this survey stand in contradiction with the claims of the Italian embassy to Brazil. While the later point to "Italian Brazilians" making up to 15% of the Brazilian population, with absolute figures varying between 25 and 30 million, and figures for the city of São Paulo as high as 60% or 6 million, the IBGE found actually a figure of 10%, which would correspond, at the time, to a total population of about 3.5 million people of Italian origin in whole set of metropolitan regions it researched, including São Paulo (and Porto Alegre, another metropolitan region with a high concentration of ''oriundi''). | The results of this survey stand in contradiction{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} with the claims of the Italian embassy to Brazil. While the later point to "Italian Brazilians" making up to 15% of the Brazilian population, with absolute figures varying between 25 and 30 million, and figures for the city of São Paulo as high as 60% or 6 million, the IBGE found actually a figure of 10%, which would correspond, at the time, to a total population of about 3.5 million people of Italian origin in whole set of metropolitan regions it researched, including São Paulo (and Porto Alegre, another metropolitan region with a high concentration of ''oriundi'').{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | ||

| {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | ||

Revision as of 02:10, 1 April 2010

Ethnic group

José Serra · Alessandra Ambrosio · Felipe Massa · Rodrigo Santoro · Fernanda Montenegro · Luiz Felipe Scolari | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Brazil: Mainly Southern and Southeastern Brazil | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Portuguese. A minority also speak Talian. | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| White Brazilian, Italian people |

An Italian Brazilian (Template:Lang-it, Template:Lang-pt) is a Brazilian citizen of full or partial Italian ancestry. The Italian government claims there are 25 million Brazilians of Italian descent, which would be the largest population of Italian background outside of Italy itself. According to demographer Miguel Ángel García the estimate of Brazilians and Argentineans with Italian ancestry is not precise, he estimates that 15 to 18 million people in Brazil have Italian ancestry. Only a minority of Italian Brazilians are recognized by the Italian legislation as Italian citizens. The reason being that many Italians renounced their Italian citizenship to acquire the Brazilian citizenship and also Italian women did not transfer citizenship to descendants until 1948. Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Italians in Brazil

Italian Brazilian ethnicity in Brazil

Italian-Brazilians or Brazilians of Italian descent are the 4th most populous group of Brazilians, just behind the descendants of Portuguese settlers, descendants of African slaves, and Amerindians. Italian surnames are common among Brazilians since up to 36 million Brazilians have Italian ancestors.

Although victims of some prejudice in the first decades and in spite of the persecution during the Second World War, Brazilians of Italian descent managed to mingle and to incorporate seamlessly into the Brazilian society.

Brazilians of Italian descent tend to be very participant in all aspects of Brazilian public life. Many Brazilian politicians, artists, footballers, models and personalities are or were of Italian descent. Amongst Italian-Brazilian one finds: several States Governors, Congressmen, mayors and ambassadors. Three Presidents of Brazil were of Italian descent (though, curiously, and unfortunately, none of them were elected to such position): Pascoal Ranieri Mazzilli (Senate president who served as interim president), Itamar Franco (elected vice-President under Fernando Collor, whom he eventually replaced as the latter was impeached), and Emílio Garrastazu Médici (third of the series of generals who presided over Brazil during the military regime). Médici was also of Basque descent.

Citizenship

According to the Brazilian Constitution, anyone born in Brazil is a Brazilian citizen by birthright. In addition, many who were born in Italy have become naturalized citizens after settling in Brazil. In recent years, a considerable number of Brazilians of Italian descent have in turn acquired Italian citizenship becoming dual citizens, as they do not lose their Brazilian citizenship by doing so. Italian law grants citizenship to those of Italian descent, on some conditions, without requiring them to live in Italy or speak fluent Italian.

History of Italian immigration in Brazil

Italian crisis in late 19th century

Main article: Italian diaspora

Italy only united as a sovereign national state in 1861. Before that Italy was politically divided in several kingdoms, ducates and other small states. It was mostly a geographic region, and a cultural-linguistic area, the Italian peninsula, more or less united by the same language. This fact influenced deeply the character of the Italian migrant. "Before 1914, the typical Italian migrant was a man without a clear national identity but with strong attachments to his town or village or region of birth, to which half of all migrants returned." The feeling of a national Italian identity and of a united ethnic group was created later on for those emigrants, when they were already in Brazil.

During the 19th century, many Italians fled the political persecutions in Italy, mainly after the failure of revolutionary movements in 1848 and 1861. Although very small, these well educated and revolutionary group of emigrants left a deep mark where they settled. In Brazil, the most famous Italians of this period were Giuseppe Garibaldi and Líbero Badaró. Despite that, the mass Italian immigration that contributed to shape Brazilian culture after the Portuguese and the German migration movements started only after the Italian unification.

During the last quarter of the 19th century, the newly united Italy suffered an economic crisis. In the Northern regions, there was unemployment due to the introduction of new techniques in agriculture, while Southern Italy remained underdeveloped and untouched by modernization in agrarian structure. Italy as a whole was very unequal, industrialization, even in the worth was still in its initial stages and illiteracy was still common in Italy (though more in the south and islands than in the north). Thus, poverty and lack of jobs and income stimulated the northern (and also southern Italians) to migrate to Brazil (as well to other countries, such as Argentina and the United States). Most of the Italian immigrants were very poor peasants, mainly farmers.

Brazilian need of immigrants

The lack of workers

In 1850, under British pressure, Brazil finally passed a law banning the international slave trade. The enforcement of this law was very irregular or hardly enforced in the beginning (this being the origin of the Brazilian expression "para inglês ver" - for the Englishmen to see - meaning something a law that is not intended to be actually enforced). But the increased pressure of the abolitionist movement, on the other hand, made clear that the days of slavery in Brazil were coming to an end. Slave trade did in fact dwindle but the slavery system within the country still endured for a few years. So the discussion about European immigration to Brazil became a priority for Brazilian landowners. The latter claimed that such migrants were or would soon become indispensable for Brazilian agriculture. They would soon win the argument and mass migration would begin in earnest.

An Agriculture Congress in 1878 in Rio de Janeiro discussed the lack of labor and proposed to the government the stimulation of European immigration to Brazil. Immigrants from Italy, Portugal and Spain were considered the best ones, because they were white and, mainly, Catholics. Therefore, the Brazilian government started to attract more Italian immigrants to the coffee plantations.

The "Whitening Project"

At the end of the 19th century, the Brazilian government was influenced by eugenics theories. According to some scholars, it was necessary to bring immigrants from Europe to enhance the Brazilian population. Brazil issued laws prohibiting the entry of Asian immigrants in 1889 and the situation changed only with the Immigration Law of 1907.

The large increase of European immigrants made some scholars believe that within a few decades black people would disappear from Brazil through miscegenation or be reduced in number by way of comparison.

On July 28, 1921, representatives Andrade Bezerra and Cincinato Braga proposed a law whose Article 1 provided: "It is prohibited to Brazil immigration of individuals from the black race." On October 22, 1923, representative Fidélis Reis produced another project of law on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: 'It is prohibited the entry of settlers from the black race in Brazil and, to Asians, it will be allowed each year, a number equal to 5% of those existing in the country.(...)'.

In 1945, the Brazilian government issued a decree favoring the entrance of European immigrants in the country: "The entry of immigrants comes from the need to preserve and develop, in the ethnic composition of the population, the more convenient features of their European ancestry".

Beginning of Italian settlement in Brazil

The Italian immigration in Brazil increased after 1850 when the enforcement of the law proscribing the international slave trade created labor shortages. Then, the Brazilian government, headed by Emperor Pedro II, instituted an open-door immigration policy towards Europeans. The Brazilian government (with or following the Emperor's support) had created the first colonies of immigrants (colônias de imigrantes) in the early 19th century. These colonies were established in rural areas of the country, being settled by European families, mainly German immigrants that settled in many areas of Southern Brazil. Following the same project, colonies with Italian immigrants were also created in southern Brazil.

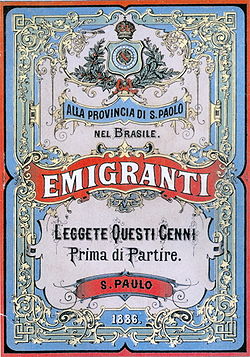

The first groups of Italians arrived in 1875, but the boom of Italian immigration in Brazil happened in late 19th century, between 1880 and 1900, when almost one million Italians arrived.

A great number of Italians was naturalized Brazilian at the end of the 19th century, when the 'Great Naturalization' conceded automatically citizenship to all the immigrants residing in Brazil prior to November 15, 1889 "unless they declared a desire to keep their original nationality within six months."

During the last years of the 19th century, the denouncements of bad conditions in Brazil increased in the press. Reacting to the public clamor and many proved cases of mistreatments of Italian immigrants, the government of Italy issued, in 1902, the Prinetti decree forbidding subsidized immigration to Brazil. In consequence, the number of Italian immigrants in Brazil fell drastically in the beginning of the 20th century, but the wave of Italian immigration continued until 1920.

Over half of the Italian immigrants came from Northern Italian regions of Veneto, Lombardy, Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna. About 30% emigrated from Veneto. On the other hand, during the 20th century, Central and Southern Italians predominated in Brazil, coming from the regions of Campania, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata and Sicily.

Statistics

The Brazilian Censuses do not ask questions about "ethnic origin", so there are no systematically comparable data about the impact of Italian immigration . Varied entities, mainly the Italian diplomatic system and commercial associations that promote bilateral commerce between Brazil and Italy , make claims about the figures of oriundi in Brazil, but none links to any actual survey. Also, if they are extrapolations of actual data on the number of immigrants, the calculations are not explained anywhere.

On the other hand, in 1998, the IBGE, within its preparation for the 2000 Census, experimentally introduced a question about "origem" (ancestry) in its "Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego" (Monthly Employment Research), in order to test the viability of introducing that variable in the Census (the IBGE ended by deciding against the inclusion of questions about it in the Census). This research interviewed about 90,000 people in six metropolitan regions (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Recife) . To this day, it remains the only actual published survey about the immigrant origin of Brazilians.

The results of this survey stand in contradiction with the claims of the Italian embassy to Brazil. While the later point to "Italian Brazilians" making up to 15% of the Brazilian population, with absolute figures varying between 25 and 30 million, and figures for the city of São Paulo as high as 60% or 6 million, the IBGE found actually a figure of 10%, which would correspond, at the time, to a total population of about 3.5 million people of Italian origin in whole set of metropolitan regions it researched, including São Paulo (and Porto Alegre, another metropolitan region with a high concentration of oriundi).

| Arrival of Italian immigrants to Brazil by periods (source: IBGE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884-1893 | 1894–1903 | 1904–1913 | 1914–1923 | 1924–1933 | 1934–1944 | 1945–1949 | 1950–1954 | 1955–1959 | |

| 510,533 | 537,784 | 196,521 | 86,320 | 70,177 | 15,312 | N/A | 59,785 | 31,263 | |

.* Comissariato Generale dell'Emigrazione .** Consulates The 1920 Census was the first one to show a more specific figure about the size of the Italian population in Brazil (558,405). However, since the 1900s the arrival of new Italian immigrants to Brazil was in full decline. The previous censuses of 1890 and 1900 had limited information (in fact, the 1900 Census never existed). In consequence, there are no official figures about the size of the Italian population in Brazil during the mass immigration period (1880–1900). There are estimates available, and the most reliable is the one done by Giorgio Mortara, even though the figures he found may have underestimated the real size of the Italian population. On the other hand, Angelo Trento believes that the Italian estimates are "certainly exagerated", and "lacking of any foundation", since they found the figure of 1,837,887 Italians in Brazil as of 1927. Another evaluation conducted by Bruno Zuculin found the presence of 997,887 Italians in Brazil as of 1927. Notice that all these figures only include people born in Italy, and not their Brazilian born descendants.

Main Italian settlements in BrazilSouthern Brazil  The main areas of Italian settlement in Brazil were the Southern and Southeastern regions, namely the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais. The first colonies to be populated by Italians were created in the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul (Serra Gaúcha). These were Garibaldi and Bento Gonçalves. These immigrants were predominantly from Veneto, in northern Italy. After five years, in 1880, the great numbers of Italian immigrants arriving caused the Brazilian government to create another Italian colony, Caxias do Sul. After initially settling in the government-promoted colonies, many of the Italian immigrants spread into other areas of Rio Grande do Sul seeking better opportunities. They created many other Italian colonies on their own, mainly in highlands, because the lowlands were already populated by German immigrants and native gaúchos. The Italian established many vineyards in the region. Nowadays, the wine produced in these areas of Italian colonization in southern Brazil is much appreciated within the country, though little is available for export. In 1875, the first Italian colonies were established in Santa Catarina, which lies immediately to the north of Rio Grande do Sul. The colonies gave rise to towns such as Criciúma, and later also spread further north, to Paraná. In the colonies of southern Brazil, Italian immigrants at first confined themselves within their own ethnic group, where they could speak their native Italian dialects and keep their culture and traditions. With time, however, they would become thoroughly integrated economically and culturally into the larger society. In any case, Italian immigration to southern Brazil was very important to the economic development, as well to the culture and ethnic formation of the region. Southeastern Brazil  A part of the immigrants settled in the colonies in Southern Brazil. However, the majority of them settled in Southeastern Brazil (mainly in the State of São Paulo). In the beginning, the government was responsible for bringing the immigrants (in most cases, paying for their transportation by ship), but later the farmers were responsible for making contracts with immigrants or specialized companies in recruiting Italian workers. Many posters were spread in Italy, with pictures of Brazil, selling the idea that everybody could become rich there by working with coffee, which was called by the Italian immigrants the green gold. Most coffee plantations were in the States of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, and in a smaller proportion also in the States of Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro was declining in the 1800s as a farming producer and São Paulo had already taken the lead as a coffee producer/exoporter at the turn of the century, as well as big producer of sugar and other important crops. Thus, migrants were naturally more attracted to the State of São Paulo and the southern states. Italians used to migrate to Brazil in families. The colono, as rural immigrants were called, had to sign a contract with the farmer and was obliged to work in the coffee plantation during a minimum period of time. However, the situation was not easy. Many Brazilian farmers were used to command slaves and treated the immigrants as indentured servants. While, in Southern Brazil, the Italian immigrants were living in relatively well-developed colonies, in Southeastern Brazil they were living in semi-slavery conditions in the coffee plantations. Many rebellions against Brazilian farmers occurred and the public denouncements caused great commotion in Italy, forcing the Italian government to issue the Prinetti decree that established barriers to immigration to Brazil.  Other parts of BrazilAlthough the majority of Brazilians of Italian descent live in the South and Southeast part of the country, in recent decades (1960s-present), people from southern Brazil, mainly of Italian descent, have played a vital role in settling and developing the vast "cerrado" grasslands of Central-West, North and the west part of Northeastern Brazil. These areas, once economically neglected, are fast becoming one the world's most important agricultural regions. The cerrado (Portuguese for thick and dense, meaning thick grassland) is a vast area of savanna-like grasslands in Brazil. In the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, Italian descendants are 5% of the population. Semi-slavery and immigration's decline In 1902, the Italian immigration to Brazil started to decline. From 1903 to 1920, only 306,652 Italians immigrated to Brazil, compared to 953,453 to Argentina and 3,581,322 to the United States. This was mainly due to the Prinetti Decree in Italy, that banned the subsidized immigration to Brazil (the Brazilian Government or landowners could not pay the passage of the immigrants anymore). Prinetti Decree was created because of the commotion in the Italian press due to the penury faced by most Italians in Brazil. The immigrants who went to Southern Brazil became small landowners and, despite the problems faced by them (dense forest, epidemics of yellow fever, lack of consumer market) the easy access to lands increased their opportunities. However, only a minority of the Italians were taken to Southern Brazil. The vast majority (over 70%) were directly taken to the coffee farms of São Paulo to replace the African slave manpower on the plantations. After the abolition of slavery in Brazil, most of the former slaves left the plantations. Very few former slaves wanted to keep working on the same plantations where they were previously enslaved, so that most Afro-Brazilian people moved to rural areas where they could live on subsistence agriculture, while others preferred to migrate to cities. Most of the country's economy was based on coffee plantations, and Brazil was already the main coffee exporter in the world (since the 1850s). As a consequence of the end of slavery and that most former slaves left the plantations, there was a labour shortage on coffee plantations. Moreover, “natural inequality of human beings”, “hierarchy of races”, Social Darwinism, Positivism and other theories were used to explain that the European workers were superior to the native workers. In consequence, passages were offered to Europeans (the so-called "subsidized immigration"), mostly to Italians, so that they could come to Brazil and work on the plantations.  Those immigrants were employed in enormous latifundia (large-scale farms), formerly employing slaves. In Brazil, there were no labour laws (the first concrete labour laws only appeared in the 1930s, under Getúlio Vargas's government) and, therefore, workers had almost no legal protection. Contracts signed by the immigrants could easily be violated by the Brazilian landowners. Accustomed to dealing with African slaves, the remnants of slavery influenced on how Brazilian landowners dealt with Italian workers: immigrants were often monitored, with extensive hours of work. In some cases, they were obliged to buy the products they needed from the landowner. Moreover, the coffee farms were located in rather isolated regions. If the immigrants became sick, they would take hours to reach the nearest hospital. The structure of labor used on farms included the labor of Italian women and children. Keeping their Italian culture was also made more difficult: the Catholic churches and Italian cultural centers were far from the farms. The immigrants who did not accept the standards imposed by the landowner were replaced by other immigrants. This forced them to accept the impositions of the landowner or they would have to leave his lands. Even though Italians were considered to be "superior" to blacks by Brazilian landowners, the situation faced by Italians in Brazil was so similar to that of the slaves that farmers called them escravos brancos (white slaves in Portuguese). The destitution faced by Italians and other immigrants in Brazil caused great commotion in the Italian press, which culminated in the Prinetti Decree in 1902. Many immigrants left Brazil after their experience on São Paulo's coffee farms. Between 1882 and 1914, 1.5 million immigrants of different nationalities came to São Paulo, while 695,000 left the state, or 45% of the total. The high numbers of Italians asking the Italian Consulate a passage to leave Brazil was so significant that in 1907 most of the Italian funds for repatriation were used in Brazil. It is estimated that, between 1890 and 1904, 223,031 (14,869 annually) Italians left Brazil, mainly after failed experiences on coffee farms. The majority of the Italians who left the country were unable to add the money they wanted. Most of these people returned to Italy, while others re-migrated to Argentina, Uruguay or to the United States. The output of immigrants concerned Brazilian landowners, who constantly complained about the lack of workers. Spanish immigrants began arriving in greater numbers, but soon Spain also started to create barriers for further immigration of Spaniards to coffee farms in Brazil. The continuing problem of lack of labor in the farms was, then, temporarily resolved with the arrival of Japanese immigrants, from 1908.  Despite the high numbers of immigrants leaving the country, the majority of the Italians remained in Brazil forever. Most of the immigrants only remained one year working on coffee farms and then they left the plantations. A small number of them earned enough money to buy their own lands, and became farmers themselves. However, the majority migrated to Brazilian urban centers. Many Italians worked in factories (in 1901, 81% of the São Paulo's factory workers were Italians). In Rio de Janeiro, a considerable number of the factory workers was also composed of Italians. In São Paulo, those workers established themselves in the center of the city, living in cortiços (degraded multifamily row houses). Those agglomerations of Italians in urban centers gave birth to typically Italian neighborhoods, such as Mooca, which is until today linked to its Italian past. Other Italians became traders, mostly itinerant traders, selling their products in different regions. A common presence on the streets of São Paulo were the Italian boys working as newspaper-boys, as an Italian traveler observed: "In the crowd, we can see many Italian boys, shabby and barefoot, selling the newspapers from the city and from Rio de Janeiro, bothering the passersby with their offerings and their shouting of street roguish". Despite the poverty and even semi-slavery conditions faced by many Italians in Brazil, over time most of this population achieved some personal success and changed their low class economic situation. Even though most of the first generation of immigrants still lived in poverty, the children of Italians, born in Brazil, often changed their social status as they diversified their field of work, leaving the poor conditions of their parents and not rarely becoming part of the local elite. AssimilationThe Brazilian population was characterized by the lack of xenophobic sentiment in relation to foreigners (with the exception of racist cases against the Japanese community). With the exception of some isolated cases of violence between Brazilians and Italians, especially between 1892 and 1896, the integration of immigrants in Brazil happened quick and peacefully. For the Italians in São Paulo, scholars suggest that this process of assimilation occurred in up to two generations. There is research that suggests that even first-generation immigrants, born in Italy, soon became assimilated in the new country. Even in Southern Brazil, where most of the Italians were living in isolated rural communities, without much contact with Brazilians, and where they kept the Italian patriarchal family structure (and therefore the father chose the wive or husband for their children, giving preference to the Italians) the assimilation process was also quick. According to the 1940 Census in Rio Grande do Sul, 393,934 people reported to speak German as their first language (11.86% of the state's population). In comparison, 295,995 reported to speak Italian, mostly dialects (8.91% of the state's population). Even though the Italian immigration was larger and more recent than the German one, the Italian group tended to be more easily assimilated. In the 1950 Census, the number of people in Rio Grande do Sul who reported to speak Italian dropped to 190,376. In São Paulo, where a larger number of Italians settled, in the 1940 census 28,910 Italian born people reported to speak Italian at home (only 13.6% of the state's Italian population). In comparison, 49.1% of the immigrants of other nationalities reported to keep speaking their native languages at home (with the exception of the Portuguese, of course). Then, the prohibition of speaking Italian, German and Japanese during the World War II was not so great to the Italian community as it was to the other two groups. A major measure of the government occurred in 1889, when the Brazilian citizenship was granted to all immigrants, although this act had little influence on their identity or assimilation process. The Italian newspapers in Brazil and also the Italian government, in turn, were uncomfortable with the assimilation of Italians in the country. This occurred mostly after the Great Naturalization period. The Italian institutions encouraged the entry of Italians in Brazilian politics, although the presence of immigrants was, initially, small. The Italian dialects came to dominate the streets of São Paulo and in some Southern localities. Over time, these languages based on Italian dialects tended to disappear and nowadays their presence is small. In the beginning, specially in rural Southern Brazil, Italians tended to marry only other Italians. On the other hand, Italians in São Paulo and, mainly, those living in urban centers tended to marry Brazilians. Over time and with the decrease of more immigrants arriving, even in Southern Brazil they started to integrate themselves with Brazilians. About the Italians in Santa Catarina, the Italian Consul asserted:

There is little information about this trend, but it was noticed a large process of integration since the World War I: between 1917 and 1923, in Rio Grande do Sul: weddings between an Italian man and a Brazilian woman (997, 66.1%); Italian woman and Brazilian man (135, 9%) and Italian man and Italian woman (375, 24.9%). These marriages between Italians and Brazilians were extremely common, mostly in the low classes, and were largely accepted for both people. However, some more closed members of the Italian community saw this integration process as negative. There are records of the repulsion caused by the cases of marriages between Italian women and black Brazilian men. The German Brazilian population was also treated by some Italians as repulsive, even though many Germans and Italians lived together in many areas of Southern Brazil. The Brazilian Indians were often treated as wild people, and cases of conflicts between Italians and Indians for the occupation of lands in Southern Brazil were not uncommon. Identity

According to the work of the sociologist Miguel Angel Garcia, who interviewed people of Italian descent in Brazil in 2002, the population of Italian origin of the country may be divided into four categories. The categories are divided among the population of Brazil of Italian origin in accordance with their degree of Italian consciousness. The estimates about their identity is based on the estimated Brazilian population of Italian descent, varying from 15 to 25 million people, according to different sources (Angel Garcia estimated that there are from 15 to 18 million people with Italian roots in Brazil, even though the official figures of the Italian government claim to be close to 25 million). According to Angel Garcia, the first category is composed of a small number of Italian immigrants, some 80,000 people. It is an aging community, which immigrated to Brazil before the 1960s and their number is now in full decline. The second category is composed of 1.5 million Brazilians who are aware of their Italian roots. This population can "truly" be called "Italian Brazilian". The third category, with 2 to 3 million people is composed of Brazilians who know they have Italian ancestors but who do not give much importance to that. The last category is composed of millions of Brazilians, perhaps 10 to 12 million people who have Italian ancestors and do not know it or do not consider it to be important. As one can see, the population of Italian origin in Brazil is very diverse, comprising a smaller number of people who still retain some sort of Italian identity and a larger number of people who are completely integrated in Brazil and do not have an Italian consciousness anymore. In a survey made by "Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego" (Monthly Employment Research) 10.41% of the Brazilians claimed to be of Italian ancestry. It was one of the largest ancestries reported by the interviewed, along with Brazilian (86.09%), Portuguese (10.46%), Amerindian (6.64%) and Black (5.09%). Brazilians tend to identify their ancestry as "Brazilian", especially the descendants of more remote ancestors, such as Africans or Indians. The descendants of more recent immigrants, including the Italians, tend to claim their ancestry to the country from where their relatives came from, even though 56.90% of the people who reported to be of Italian ancestry also reported to be of Brazilian ancestry. In the Italian group, the older generations tend to identify their Italian ancestry more strongly, while the younger generations identify their ancestry as Brazilian, which reflects the process of assimilation among young people. Prosperity

Italians were divided in two groups in Brazil. Those in Southern Brazil lived in rural colonies, in contact mostly with other Italian immigrants. On the other hand, Italians living in Southeast Brazil, the most populated region of the country, integrated into Brazilian society quickly. After some years working in coffee plantations, some immigrants earned enough money to buy their own land and become farmers themselves. Others left the rural areas and moved to urban centres, mainly São Paulo, Campinas, São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto. A small minority became very rich in the process, and attracted more Italian immigrants. In the early 20th century, São Paulo was known as the city of the Italians, because 30% of its inhabitants were Italians. The city of São Paulo has the second highest population of people with Italian ancestry in the world, second only to Rome. In Campinas, street signs in Italian were frequent, a large commercial and services sector owned by Italians developed, and more than 60% of the population had Italian surnames. Today, nearly 30% of the population of Belo Horizonte is of Italian descent. Italians and their descendants were also quick to organize themselves and establish mutual aid societies (such as the Circolo Italiano), hospitals, schools (such as the Istituto Dante Alighieri, in São Paulo), labor unions, newspapers (such as La Fanciulla), magazines, radio stations and even soccer teams (such as Palestra Italia, later renamed to Portuguese Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras in São Paulo, and Cruzeiro in Belo Horizonte during World War II). Italian immigrants were very important to the development of many big cities of Brazil, such as São Paulo, Porto Alegre, Curitiba and Belo Horizonte. Bad conditions in rural areas of Brazil made thousands of Italians move to these big cities. Most of them became laborers and participated actively in the industrialization of Brazil in the early 20th century. Others became investors, bankers and industrialists, such as Andrea Matarazzo, whose family became the richest industrialists in São Paulo, with a holding of more than 200 industries and businesses. Characteristics of Italian Immigration in Brazil

Areas of originMost of the Italian immigrants to Brazil came from Northern Italy; however, they were not distributed homogeneously along the extensive Brazilian regions. In the state of São Paulo, the Italian community was more diverse including a large number of people from the South and from the Center of Italy. Even today, 42% of the Italians in Brazil came from the Northern regions, 36% from central regions and only 22% from the south of Italy. Brazil is the only country with a large Italian community where the Southern Italian immigrants are minority. In the first decades, the vast majority of the immigrants came from the North. Since Southern Brazil received most of the early settlers, the vast majority of the immigrants in this region came from the extreme North of Italy, mainly from Veneto and particularly from the provinces of Vicenza, Treviso and Verona. In Rio Grande do Sul, many came from Cremona, Mantua, from parts of Brescia, and also from Bergamo, in the region of Lombardy, close to Veneto. The regions of Trento, particularly the area of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and of Friuli-Venezia Giulia also sent many immigrants to the South of Brazil. Of the immigrants in Rio Grande do Sul, 54% came from the Veneto, 33% from Lombardy, 7% from Trento, 4.5% from Friuli-Venezia Giulia and only 1.5% from other parts of Italy. Starting in the early 20th century, the agrarian crisis also started to affect Southern Italy and many of them immigrated to Brazil. The Southerners went mostly to the state of São Paulo, since it was in need of workers to embrace the coffee plantations. Among the Italian immigrants in São Paulo, most came from Calabria, Campania and Veneto. Areas of settlementAmong all Italians who immigrated to Brazil, 70% went to the State of São Paulo. In consequence, São Paulo has more people with Italian ancestry than any region of Italy itself. The rest went mostly to the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais. Due to the internal migration, many Italians, second and third generations descendants, moved to other areas. In the early 20th century, many rural Italian workers from Rio Grande do Sul migrated to the west of Santa Catarina and then further north to Paraná. More recently, third and fourth generations have been migrating to other areas; thus it is possible to find people of Italian descent in Brazilian regions where the immigrants had never settled, such as in the Cerrado region of Central-West, in the Northeast and in the Amazon rainforest area, in the extreme North of Brazil. Italian influences in Brazil Italian influence on Brazilian PortugueseNowadays, most Brazilians with Italian ancestry speak Portuguese as their native language. During the Second World War, the public use of Italian, German and Japanese was forbidden. The Italian dialects have influenced the Portuguese spoken in some areas of Brazil. In São Paulo, the diversity of the languages spoken by immigrants resulted in an accent which differs substantially from the Caipira accent that prevailed before their arrival. The new accent resulted from the influence of Italian accents on Portuguese. Currently, the Italian influence on Portuguese spoken in São Paulo is not as great as in the past, although the accent of the city's inhabitants still has some traces of the Italian accents common in the beginning of the 20th century. It is noteworthy that the influence of Italian on the spoken language of residents of São Paulo is fairly widespread and often found among those not of Italian descent. The lexical influence of Italian on Brazilian Portuguese, however, has remained quite small. A similar phenomenon occurred in the countryside of Rio Grande do Sul, but encompassing almost exclusively those of Italian origin. On the other hand, there exists a different phenomenon; Talian, a language which emerged mostly in the northeastern part of the state (Serra Gaúcha). Talian is a language belonging to the Venetian language, but with influences from other Italian dialects and Portuguese. In southern Brazilian rural areas marked by bilingualism, even among the monolingual Portuguese-speaking population, the Italian-influenced accent is fairly typical. St. Vito Festival St. Vito Festival is one of the most important Italian festivals in São Paulo. It is a celebration in honor of Saint Vito, the patron saint of Polignano a Mare, a city in the Puglia region, in Italy. Many Italian immigrants in Brás, a São Paulo district, came from Puglia. Festa de São Vito is also a time when the Italian community in São Paulo gathers to party and eat traditional food. Other important Italian celebrations in São Paulo are Our Lady of Casaluce, also in Brás (May), Our Lady of Achiropita, in Bela Vista (August), and St. Gennaro, in Mooca (September). Italian immigrants from the Puglia region who moved in great numbers to the Brás neighborhood in São Paulo at the end of the nineteenth century brought along a devotion to Saint Vito, a Christian martyr who was killed in June of 303 a.D. Just like Polignano a Mare, eventually Brás had a church devoted to St. Vito. An association was formed and hosted the first festival in June 1919. As São Paulo grew, so did the Italian community and St. Vito Festival. Today, about 6 million of São Paulo's 10,886,518 inhabitants are Italians and descendants (known as "oriundi"), according to statistics provided by Conscre, a São Paulo state council for foreign communities. An estimated 140,000 people are expected to attend the festival in 2008. Other Influences

See also

References

Bibliografia

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||