| Revision as of 05:05, 30 June 2010 editKristoferb (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,124 edits Undid revision 370876953 by Editor182 (talk) - Vandalism← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:54, 30 June 2010 edit undoEditor182 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,053 edits Reversion done by an administrator must be discussed on their talk page.Next edit → | ||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

| ])]] | ])]] | ||

| ])]] | ])]] | ||

| ])]] | |||

| According to Pfizer, sertraline is ] in individuals taking ]s or the ] ] (Orap). Sertraline concentrate contains alcohol, and is therefore contraindicated with ] (Antabuse). The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution". Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.<ref name="zoloftpi">{{cite web |url=http://www.zoloft.com |title=Zoloft Prescribing Information for the U.S.|format= PDF|publisher=Pfizer |accessdate=2008-04-26}}</ref> | According to Pfizer, sertraline is ] in individuals taking ]s or the ] ] (Orap). Sertraline concentrate contains alcohol, and is therefore contraindicated with ] (Antabuse). The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution". Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.<ref name="zoloftpi">{{cite web |url=http://www.zoloft.com |title=Zoloft Prescribing Information for the U.S.|format= PDF|publisher=Pfizer |accessdate=2008-04-26}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 07:54, 30 June 2010

"Lustral" redirects here. For the electronic music band, see Lustral (band). Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 44% |

| Protein binding | 98.5% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (N-demethylation mainly by CYP2B6) |

| Elimination half-life | Approximately 26 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

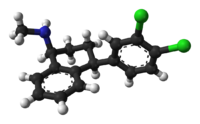

| Formula | C17H17Cl2N |

| Molar mass | 306.229 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

| (verify) | |

Sertraline hydrochloride (brand name Zoloft) is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It was introduced to the market by Pfizer in 1991. Sertraline is primarily used to treat major depression in adult outpatients as well as obsessive–compulsive, panic, and social anxiety disorders in both adults and children. In 2007, it was the most prescribed antidepressant on the U.S. retail market, with 29,652,000 prescriptions.

The efficacy of sertraline for depression is similar to that of older tricyclic antidepressants, but its side effects are much less pronounced. Differences with newer antidepressants are subtler and also mostly confined to side effects. Evidence suggests that sertraline may work better than fluoxetine (Prozac) for some subtypes of depression. Sertraline is highly effective for the treatment of panic disorder, but cognitive behavioral therapy is a better treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder, whether by itself or in combination with sertraline. Although approved for social phobia and posttraumatic stress disorder, sertraline leads to only modest improvement in these conditions. Sertraline also alleviates the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and can be used in sub-therapeutic doses or intermittently for its treatment.

Sertraline shares the common side effects and contraindications of other SSRIs, with high rates of nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, and sexual side effects; however, it does not cause weight gain, and its effects on cognition are mild. The unique effect of sertraline on dopaminergic neurotransmission may be related to its favorable action on cognitive functions. In pregnant women taking sertraline, the drug was present in significant concentrations in fetal blood, and was also associated with a higher rate of various birth defects. Similarly to other antidepressants, the use of sertraline for depression may be associated with a higher rate of suicidality. Due to the rarity of this side effect, statistically significant data are difficult to obtain, and suicidality continues to be a subject of controversy.

History

The history of sertraline dates back to the early 1970s, when Pfizer chemist Reinhard Sarges invented a novel series of psychoactive compounds based on the structures of neuroleptics chlorprothixene and thiothixene. Further work on these compounds led to tametraline, a norepinephrine and weaker dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Development of tametraline was soon stopped because of undesired stimulant effects observed in animals. A few years later, in 1977, pharmacologist Kenneth Koe, after comparing the structural features of a variety of reuptake inhibitors, became interested in the tametraline series. He asked another Pfizer chemist, Willard Welch, to synthesize some previously unexplored tametraline derivatives. Welch generated a number of potent norepinephrine and triple reuptake inhibitors, but to the surprise of the scientists, one representative of the generally inactive cis-analogs was a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Welch then prepared stereoisomers of this compound, which were tested in vivo by animal behavioral scientist Albert Weissman. The most potent and selective (+)-isomer was taken into further development and eventually named sertraline. Weissman and Koe recalled that the group did not set up to produce an antidepressant of the SSRI type—in that sense their inquiry was not "very goal driven", and the discovery of the sertraline molecule was serendipitous. According to Welch, they worked outside the mainstream at Pfizer, and even "did not have a formal project team". The group had to overcome initial bureaucratic reluctance to pursue sertraline development, as Pfizer was considering licensing an antidepressant candidate from another company.

Sertraline was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991 based on the recommendation of the Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee; it had already become available in the United Kingdom the previous year. The FDA committee achieved a consensus that sertraline was safe and effective for the treatment of major depression. During the discussion, Paul Leber, Director of the FDA Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products, noted that granting approval was a "tough decision", since the treatment effect on outpatients with depression had been "modest to minimal". Other experts emphasized that the drug's effect on inpatients had not differed from placebo and criticized poor design of the trials by Pfizer. For example, 40% of participants dropped out of the trials, significantly decreasing their validity.

Sertraline entered the Australian market in 1994 and became the most often prescribed antidepressant in 1996 (2004 data). It was measured as among the top ten drugs ranked by cost to the Australian government in 1998 and 2000–01, having cost $45 million and $87 million in subsidies respectively. Sertraline is less popular in the UK (2003 data) and Canada (2006 data)—in both countries it was fifth, based on the number of prescriptions.

Until 2002, sertraline was only approved for use in adults ages 18 and over; that year, it was approved by the FDA for use in treating children aged 6 or older with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In 2003, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a guidance that, apart from fluoxetine (Prozac), SSRIs are not suitable for the treatment of depression in patients under 18. However, sertraline can still be used in the UK for the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents. In 2005, the FDA added a black box warning concerning pediatric suicidality to all antidepressants, including sertraline. In 2007, labeling was again changed to add a warning regarding suicidality in young adults ages 18 to 24.

The U.S. patent for Zoloft expired in 2006, and sertraline is now available in generic form.

Indications

Sertraline has been approved for the following indications: major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), panic disorder and social phobia (social anxiety disorder).

Depression

The original pre-marketing clinical trials demonstrated only weak-to-moderate efficacy of sertraline for depression. Nevertheless, a considerable body of later research established it as one of the drugs of choice for the treatment of depression in outpatients. Despite the negative results of early trials, sertraline is often used to treat depressed inpatients as well. Sertraline is effective for both severe depression and dysthymia, a milder and more chronic variety of depression. In several double-blind studies, sertraline was consistently more effective than placebo for dysthymia and comparable to imipramine (Tofranil) in that respect. Sertraline also improved the depression of dysthymic patients to a greater degree than group cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal psychotherapy, and adding psychotherapy to sertraline did not seem to enhance the outcome. These results also held up in a two-year follow-up of sertraline-treated and interpersonal-therapy-treated groups. In the treatment of depression accompanied by OCD, sertraline performed significantly better than desipramine (Norpramine) on the measures of both OCD and depression. Sertraline was equivalent to imipramine for the treatment of depression with co-morbid panic disorder, but it was better tolerated. Sertraline treatment of depressed patients with co-morbid personality disorders improved their personality traits, and this improvement was almost independent from the improvement of their depression.

Comparison with tricyclic antidepressants

The effect of sertraline on the core symptoms of depression is similar to that of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs); however, it is better tolerated and results in a better quality of life. Similar improvement of depression scores was seen in studies comparing sertraline with clomipramine (Anafranil) and amitriptyline (Elavil). At the same time, sertraline resulted in a much lower rate of side effects than amitriptyline (49%, vs. 72% for amitriptyline and 32% for placebo), particularly dry mouth, somnolence, constipation and increased appetite. However, there were more cases of nausea and sexual dysfunction in the sertraline group. Participants taking sertraline showed a greater improvement of the subjective quality of life on such measures as work satisfaction, subjective feeling, perceptions of health and cognitive function.

A large and thorough double-blind study compared sertraline—prescribed for chronic (longer than two years) depression or depression with dysthymia—to the "gold standard" of depression treatment, the TCA imipramine (Tofranil). Sertraline was equivalent to imipramine for both of these indications during the first 12 weeks of the study and the 16-week continuation phase. Only 11% of patients on sertraline suffered from severe side effects vs. 24% on imipramine. Constipation, dizziness, tremor, dry mouth, micturition disorder and sweating were observed more often with imipramine, and diarrhea and insomnia with sertraline. Patients on sertraline also reported significantly better social and physical functioning. The 30% of the patients treated with sertraline or imipramine who achieved a remission during the trial did not differ from the healthy population on the measures of marital, parental, physical and work functioning and were close to normal on social adjustment and other measures of interpersonal functioning.

TCAs as a group are considered to work better than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for melancholic depression and in inpatients, but not necessarily for simply more severe depression. In line with this generalization, sertraline was no better than placebo in inpatients (see History) and as effective as the TCA clomipramine for severe depression. The comparative efficacy of sertraline and TCAs for melancholic depression has not been studied. A 1998 review suggested that, due to its pharmacology, sertraline may be more efficacious than other SSRIs and equal to TCAs for the treatment of melancholic depression. A later open-label study of general practice patients, funded by Pfizer, found that sertraline had equal efficacy in melancholic vs. non-melancholic patients, as well as in previous TCA non-responders vs. all other patients.

Comparison with other antidepressants

According to a meta-analysis of 12 new-generation antidepressants, sertraline and escitalopram are the best in terms of efficacy and acceptability in the acute-phase treatment of adults with unipolar major depression. Reboxetine was significantly worse.

Comparative clinical trials demonstrated that sertraline's efficacy in depression is similar to that of moclobemide (Aurorix), nefazodone (Serzone), escitalopram (Lexapro), bupropion (Wellbutrin), citalopram (Celexa), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil) and mirtazapine (Remeron). Compared to patients on bupropion, those taking sertraline had much higher rates of sexual dysfunction (61% vs. 10% for men and 41% vs. 7% for women), nausea, diarrhea, somnolence and sweating, as well as a higher rate of discontinuation due to side effects (13% vs. 3%). Meta-analysis by the independent Cochrane Collaboration indicated that sertraline is more effective for the treatment of depression than fluoxetine (Prozac), with a 1.4 times higher probability of response, and is possibly better tolerated. The greatest advantage of sertraline over fluoxetine was seen among severely depressed and melancholic patients with low anxiety. Comparative studies of sertraline and venlafaxine (Effexor) found marginal differences in favor of venlafaxine or no differences.

Depression in the elderly

Sertraline used for the treatment of depression in elderly (older than 60) patients was superior to placebo and comparable to another SSRI fluoxetine, and TCAs amitriptyline, nortriptyline (Pamelor) and imipramine. Sertraline had much lower rates of adverse effects than these TCAs, with the exception of nausea, which occurred more frequently with sertraline. In addition, sertraline appeared to be more effective than fluoxetine or nortriptyline in the older-than-70 subgroup. A 2003 trial of sertraline vs. placebo in elderly patients showed a statistically significant (that is, unlikely to occur by chance), but clinically very modest improvement in depression and no improvement in quality of life. The authors were sharply criticized by Bernard Carroll, a one-time chairman of the FDA Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee, for presenting these results as positive: "The study has all the hallmarks of an 'experimercial,' a cost-is-no-object exercise driven by a corporate sponsor to create positive publicity for its product in a market niche. ... Thus does the corporate mandate to put lipstick on the pig prevail over the academic duty to communicate independent analyses of the data."

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated sertraline to be efficacious for the treatment of OCD in adults and children. It was better tolerated and, based on intention to treat analysis, performed better than the gold standard of OCD treatment clomipramine. Sertraline was also marginally more efficacious than fluoxetine (Prozac). It is generally accepted that the sertraline dosages necessary for the effective treatment of OCD are higher than the usual dosage for depression. The onset of action is also slower for OCD than for depression. The treatment recommendation is to start treatment with a half of maximal recommended dose for at least two months. After that, the dose can be raised to the maximal recommended in the cases of unsatisfactory response. If the patient was completely non-responsive to the maximal recommended dose of sertraline (200 mg), further increasing the dose did not significantly improve the response rates. However, patients with a partial but incomplete response to sertraline at 200 mg did see a clinically significant reduction in symptoms, when the dose was titrated up to a maximum of 400 mg. Incidence of side effects at 400 mg was found to be comparable to 200 mg.

The patients who responded to sertraline during a short-term trial sustained their improvement when the treatment continued for a year and longer. At the same time, the prolonged treatment may not be necessary for everyone. In a double-blind study, half of the subjects who had been successfully treated for a year were discontinued from sertraline. Only 48% of the patients in the discontinuation group were able to complete the study; however, these completers fared as well as the subjects who continued taking sertraline.

CBT alone was superior to sertraline in both adults and children; however, the best results were achieved using a combination of these treatments. A review mentions that sertraline can be used for the treatment of OCD co-morbid with Tourette syndrome; however, sertraline may cause exacerbation of tics in Tourette syndrome.

Panic disorder

In four large double-blind studies sertraline was shown to be superior to placebo for the treatment of panic disorder. The response rate was independent of the dose (50–200 mg). In addition to decreasing the frequency of panic attacks by about 80% (vs. 45% for placebo) and decreasing general anxiety, sertraline resulted in improvement of quality of life on most parameters. The patients rated as "improved" on sertraline reported better quality of life than the ones who "improved" on placebo. The authors of the study argued that the improvement achieved with sertraline is different and of a better quality than the improvement achieved with placebo. Sertraline was equally effective for men and women and for patients with or without agoraphobia. Previous unsuccessful treatment with benzodiazepines did not diminish its efficacy. However, the response rate was lower for the patients with more severe panic. Double-blind comparative studies found sertraline to have the same effect on panic disorder as paroxetine (Paxil) or the gold standard of panic disorder treatment alprazolam (Xanax). While imprecise, comparison of the results of trials of sertraline with separate trials of other anti-panic agents (clomipramine (Anafranil), imipramine (Tofranil), clonazepam (Klonopin), alprazolam, fluvoxamine (Luvox) and paroxetine) indicates approximate equivalence of these medications. Although panic disorder is considered to be a chronic condition, continuous treatment may not be necessary for everyone. In a double-blind discontinuation trial, abruptly stopping sertraline after one year of successful treatment resulted in relapse of the disorder in 33% of the patients vs. 13% of those who continued taking sertraline over the following 28 weeks. The patients experienced distinct withdrawal syndrome, expressed primarily as insomnia and dizziness, and the authors noted that a significant part of the relapse rate among the discontinued patients could possibly be accounted for by the withdrawal syndrome. Confirming these hypotheses, in another study, gradual discontinuation of sertraline after 12 weeks of treatment did not lead to the return of panic symptoms. In the same study, discontinuation of paroxetine caused exacerbation of panic in about a fifth of the previously responding patients. The authors attributed this difference to the more severe withdrawal syndrome with paroxetine, which even discontinuation over three weeks could not remedy.

Social phobia

Sertraline has been successfully used for the treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder). In a flexible dosing study, it appeared that a higher dose range was needed for adequate response. Furthermore, improvement was achieved slowly, separating from the placebo response only by week six, and continuing to increase until week 12. The response was higher among the patients with later onset, especially adult onset, of the disorder. Among the different rating scales, the clinician-rated global improvement demonstrated the highest difference vs. placebo, while the patient self-rated quality of life differed from placebo only modestly. The greatest improvement of quality of life was observed among the most impaired patients. In addition to psychological components of social phobia, such as fear and avoidance, sertraline also ameliorated some physiological components, such as blushing and palpitations but not sweating and trembling. In a four-way placebo-controlled comparison trial of sertraline and exposure therapy, sertraline performed significantly better than placebo, while the exposure therapy resulted in only marginal improvement. The combination of sertraline and exposure therapy was not significantly better than sertraline alone; however, it appeared that the response was achieved faster with the combined treatment.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

According to several double-blind studies, sertraline is effective in alleviating the symptoms of PMDD, a severe form of premenstrual syndrome. Significant improvement was observed in 50–60% of cases treated with sertraline vs. 20–30% of cases on placebo. The improvement began during the first week of treatment, and in addition to mood, irritability, and anxiety, improvement was reflected in better family functioning, social activity and general quality of life. Work functioning and physical symptoms, such as swelling, bloating and breast tenderness, were less responsive to sertraline. Despite the well-known sexual side effects of sertraline, significantly higher improvement of sexual functioning was achieved by the sertraline group as compared to the placebo group. A three-way comparison of sertraline, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor tricyclic antidepressant desipramine, and placebo demonstrated the superiority of sertraline, while desipramine fared no better than placebo. Taking sertraline only during the luteal phase, that is, the 12–14 days before menses, was shown to work as well as continuous treatment. Although the luteal-phase treatment may be more acceptable to patients, there have been indications that by the end of a three-month period it is less well-tolerated than the continuous treatment. The study authors suggested that the continuous treatment may allow the tolerance to side effects of sertraline to develop faster. The most recent (2006) trial findings indicate that continuous treatment with sub-therapeutic doses of sertraline (25 mg vs. usual 50–100 mg) may both afford the highest effectiveness and minimize the side effects.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Two double-blind placebo-controlled studies confirmed the efficacy of sertraline for severe chronic PTSD in civilians, with the mean duration of the illness more than ten years. Physical or sexual assault was the traumatic event for more than 60% of the subjects, and 75% of them were women. Over the 12-week period, 53–60% of the patients treated with sertraline were much or very much improved vs. 32–38% for placebo. The treatment was continued for another year with some participants from both trials. The condition of the responders further improved; some of the patients who did not respond to the initial 12-week trial slowly improved as well, so that about half of them were classified as responders by the end of the following 24 weeks. The authors noted that the medication worked more slowly for those with more severe symptoms. Discontinuation of the successful treatment after six months resulted in the return of the PTSD symptoms in 52% of the patients vs. 16% in those who continued taking sertraline. Longer-term treatment has been advocated in such cases.

Three-way (placebo–sertraline–third antidepressant) comparison trials of sertraline for PTSD found it to be better than placebo and equivalent to venlafaxine (Effexor) or citalopram (Celexa), and in a two-way comparison it had the same efficacy as nefazodone (Serzone). Sertraline was not effective for veterans with combat-related PTSD.

Other indications

Two large placebo-controlled clinical trials of sertraline for generalized anxiety disorder have been conducted. While one trial demonstrated highly significant improvements on all measures used, including anxiety, depression and quality of life, the other showed only marginal improvement of anxiety, and insignificant improvement of quality of life. Small double-blind studies of sertraline for eating disorders, such as binge eating disorder, night eating syndrome and bulimia nervosa indicated its effectiveness.

Although sertraline can be used for the treatment of premature ejaculation a comparative study found it to be inferior to another SSRI, paroxetine. A general disadvantage of SSRIs is that they require continuous daily treatment to delay ejaculation significantly. For the occasional "on-demand", a few hours before coitus, treatment, clomipramine gave better results than paroxetine in one study, while in another study both sertraline and clomipramine were indistinguishable from the pause–squeeze technique and inferior to paroxetine. The most recent research, conducted in 2007, suggests that on-demand treatment with sildenafil (Viagra) offers a dramatic improvement in ejaculation delay and sexual satisfaction as compared with daily paroxetine, with on-demand sertraline, paroxetine or clomipramine, and with the pause–squeeze technique.

A small study suggested that sertraline may help some children and adolescents with refractory syncope. Subsequent case reports indicated that sertraline may itself cause syncope in adolescents and that sertraline treatment of syncope may make it more frequent.

Adverse effects

According to Pfizer, sertraline is contraindicated in individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors or the antipsychotic pimozide (Orap). Sertraline concentrate contains alcohol, and is therefore contraindicated with disulfiram (Antabuse). The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution". Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.

Among the common adverse effects associated with sertraline and listed in the prescribing information, those with the greatest difference from placebo are nausea (25% vs. 11% for placebo), ejaculation failure (14% vs. 1% for placebo), insomnia (21% vs. 11% for placebo), diarrhea (20% vs. 10% for placebo), dry mouth (14% vs. 8% for placebo), somnolence (13% vs. 7% for placebo), dizziness (12% vs. 7% for placebo), tremor (8% vs. 2% for placebo) and decreased libido (6% vs. 1% for placebo). Those that most often resulted in interruption of the treatment were nausea (3%), diarrhea (2%) and insomnia (2%). Sertraline appears to be associated with microscopic colitis, a rare condition of unknown etiology.

Akathisia—that is, "inner tension, restlessness, and the inability to stay still"—caused by sertraline was observed in 16% of patients in a case series. This and other reports note that akathisia begins soon after the initiation of treatment or a dose increase; often, several hours after taking the medication. Akathisia usually disappears within several days after sertraline is stopped or its dose is decreased. In some cases, clinicians confused akathisia with anxiety and increased the dose of sertraline, causing further worsening of the patients' symptoms. Experts note that because of the possible link of akathisia with suicide and the distress it causes to the patient, "it is of vital importance to increase awareness amongst staff and patients of the symptoms of this relatively common condition".

Over more than six months of sertraline therapy for depression, patients showed an insignificant weight increase of 0.1%. Similarly, a 30-month-long treatment with sertraline for OCD resulted in a mean weight gain of 1.5% (1 kg). Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the weight gain was lower for fluoxetine (Prozac) (1%) but higher for citalopram (Celexa), fluvoxamine (Luvox) and paroxetine (Paxil) (2.5%). Only 4.5% of the sertraline group gained a large amount of weight (defined as more than 7% gain). This result compares favorably with placebo, where, according to the literature, 3–6% of patients gained more than 7% of their initial weight. The large weight gain was observed only among female members of the sertraline group; the significance of this finding is unclear because of the small size of the group.

Over a two-week treatment of healthy volunteers, sertraline slightly improved verbal fluency but did not affect word learning, short-term memory, vigilance, flicker fusion time, choice reaction time, memory span, or psychomotor coordination. In spite of lower subjective rating, that is, feeling that they performed worse, no clinically relevant differences were observed in the objective cognitive performance in a group of people treated for depression with sertraline for 1.5 years as compared to healthy controls. In children and adolescents taking sertraline for six weeks for anxiety disorders, 18 out of 20 measures of memory, attention and alertness stayed unchanged. Divided attention was improved and verbal memory under interference conditions decreased marginally. Because of the large number of measures taken, it is possible that these changes were still due to chance.

Overdosage

Acute overdosage is often manifested by emesis, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia and seizures. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of sertaline and norsertraline, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities.

Birth defects and effects on breast-fed infants

The studies comparing the levels of sertraline and its principal metabolite, desmethylsertraline, in mother's blood to their concentration in umbilical cord blood at the time of delivery indicated that fetal exposure to sertraline and its metabolite is approximately a third of the maternal exposure. The use of sertraline during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with increased odds of the following birth defects: omphalocele (six-fold), anal atresia and limb reduction defects (four-fold), and septal defects (two-fold). Concentration of sertraline and desmethylsertraline in breast milk is highly variable and, on average, is of the same order of magnitude as their concentration in the blood plasma of the mother. As a result, more than half of breast-fed babies receive less than 2 mg/day of sertraline and desmethylsertraline combined, and in most cases these substances are undetectable in their blood. No changes in serotonin uptake by the platelets of breast-fed infants were found, as measured by their blood serotonin levels before and after their mothers began sertraline treatment.

Sexual side effects

Like other SSRIs, sertraline is associated with sexual side effects, including arousal disorder and difficulty achieving orgasm. The observed frequency of sexual side effects depends greatly on whether they are reported by patients spontaneously, as in the manufacturer's trials, or actively solicited by the physicians. There have been several double-blind studies of sexual side effects comparing sertraline with placebo or other antidepressants. While nefazodone (Serzone) and bupropion did not have negative effects on sexual functioning, 67% of men on sertraline experienced ejaculation difficulties vs. 18% before the treatment (or 61% vs. 0% according to another paper). Similarly, in a group of women who initially did not have difficulties achieving orgasm, 41% acquired this problem during treatment with sertraline. A 40% rate of orgasm dysfunction (vs. 9% for placebo) on sertraline was observed in a mixed group in another study. Sexual arousal disorder, defined as "inadequate lubrication and swelling for women and erectile difficulties for men," occurred in 12% of patients on sertraline as compared with 1% of patients on placebo. The mood improvement resulting from the treatment with sertraline counteracted these side effects, so that sexual desire and overall satisfaction with sex stayed the same as before the sertraline treatment. However, under the action of placebo the desire and satisfaction slightly improved.

Suicidality

The FDA requires all antidepressants, including sertraline, to carry a black box warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25. This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts that found a 2-fold increase of suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and a 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group.

Suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare. For the above analysis, the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications in order to obtain statistically significant results. Considered separately, sertraline use in adults decreased the odds of suicidality with a marginal statistical significance by 37% or 50% depending on the statistical technique used. The authors of the FDA analysis note that "given the large number of comparisons made in this review, chance is a very plausible explanation for this difference". The more complete data submitted later by the sertraline manufacturer Pfizer indicated increased suicidality. Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase of odds of suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the patients on sertraline as compared to the ones on placebo.

Discontinuation syndrome

Main article: SSRI discontinuation syndromeAbrupt interruption of sertraline treatment may result in withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome. This syndrome occurred in 60% of the remitted depressed patients taking sertraline in a blind discontinuation study, as compared to 14% of patients on fluoxetine and 66% of patients on paroxetine. During the 5–8-day period when sertraline was temporarily replaced by placebo, the most frequent symptoms (reported by more than a quarter of patients) were irritability, agitation, dizziness, headache, nervousness, crying, emotional lability, bad dreams and anger. Around a third experienced mood worsening to the level generally associated with a major depressive episode. In a double-blind study of remitted panic disorder patients, abrupt discontinuation of sertraline treatment resulted in insomnia and dizziness (both 16–17% vs. 4% for continuing treatment), although headache, depression and malaise did not increase significantly. In another double-blind study of recovered panic disorder patients, the withdrawal syndrome was completely avoided when sertraline was gradually discontinued over three weeks, while patients stopping paroxetine treatment still suffered from it.

Mechanism of action

Sertraline is primarily a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI), with a Ki=3.4 nM. Therapeutic doses of sertraline (50–200 mg/day) taken by patients for four weeks resulted in 80–90% inhibition of serotonin transporter (SERT) in striatum as measured by positron emission tomography. A daily 9 mg dose was sufficient to inhibit 50% of SERT.

Sertraline is also a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, with a Ki=260 nM, a σ1 receptor agonist with 5% of its SRI potency, and an α1-adrenoreceptor antagonist with 1–10% of its SRI potency.

Pharmacokinetics

Sertraline is absorbed slowly when taken orally, achieving its maximal concentration in the plasma 4–6 hours after ingestion. In the blood, it is 98.5% bound to plasma proteins. Its half-life in the body is 13–45 hours and, on average, is about 1.5 times longer in women (32 hours) than in men (22 hours), leading to a 1.5-times-higher exposure in women. According to in vitro studies, sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome 450 isoforms: CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. It appeared unlikely that inhibition of any single isoform could cause clinically significant changes in sertraline pharmacokinetics. No differences in sertraline pharmacokinetics were observed between people with high and low activity of CYP2D6; however, poor CYP2C19 metabolizers had a 1.5-times-higher level of sertraline than normal metabolizers. In vitro data also indicate that the inhibition of CYP2B6 should have even greater effect than the inhibition of CYP2C19, while the contribution of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 to the metabolism of sertraline would be minor. These conclusions have not been verified in human studies. Sertraline can be deaminated in vitro by monoamine oxidases; however, this metabolic pathway has never been studied in vivo. The major metabolite of sertraline, desmethylsertraline, is about 50 times weaker as a serotonin transporter inhibitor than sertraline and its clinical effect is negligible.

Interactions

Sertraline is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 in vitro. Accordingly, in human trials it caused increased blood levels of CYP2D6 substrates such as metoprolol, dextromethorphan, desipramine, imipramine and nortriptyline, as well as the CYP3A4/CYP2D6 substrate haloperidol. This effect is dose-dependent; for example, co-administration with 50 mg of sertraline resulted in 20% greater exposure to desipramine, while 150 mg of sertraline led to a 70% increase. In a placebo-controlled study, the concomitant administration of sertraline and methadone caused a 40% increase in blood levels of the latter, which is primarily metabolized by CYP2B6. Sertraline is often used in combination with stimulant medication for the treatment of co-morbid depression and/or anxiety in ADHD. Studies have shown there was an increase in the concentration of amphetamine in the brain in rats pretreated with 5 mg/kg sertraline. Sertraline has been shown to augment the locomotor stimulatory effect of amphetamine by decreasing the metabolism of amphetamine, perhaps via actions on cytochrome P450 isozymes.

Sertraline had a slight inhibitory effect on the metabolism of diazepam, tolbutamide and warfarin, which are CYP2C9 or CYP2C19 substrates; this effect was not considered to be clinically relevant. As expected from in vitro data, sertraline did not alter the human metabolism of the CYP3A4 substrates erythromycin, alprazolam, carbamazepine, clonazepam, and terfenadine; neither did it affect metabolism of the CYP1A2 substrate clozapine.

Sertraline had no effect on the actions of digoxin and atenolol, which are not metabolized in the liver. Case reports suggest that taking sertraline with phenytoin or zolpidem may induce sertraline metabolism and decrease its efficacy, and that taking sertraline with lamotrigine may increase the blood level of lamotrigine, possibly by inhibition of glucuronidation.

Clinical reports indicate that interaction between sertraline and the MAOIs isocarboxazid and tranylcypromine may cause serotonin syndrome. In a placebo-controlled study in which sertraline was co-administered with lithium, 35% of the subjects experienced tremors, while none of those taking placebo did.

Controversy

The brand-name form of sertraline, Zoloft, was advertised to consumers by Pfizer using the following wording: "While the cause is unknown, depression may be related to an imbalance of natural chemicals between nerve cells in the brain. Prescription Zoloft works to correct this imbalance. You just shouldn't have to feel this way anymore." An essay published in the journal PLoS Medicine noted that there is no scientific support for the "serotonin imbalance" theory of depression, and criticized Pfizer and manufacturers of other SSRIs for using it. When asked to comment on this apparent breach of federal regulations, the FDA answered that such "reductionist statements" are acceptable to explain the neurochemistry of depression "to the fraction of the public that functions at no higher than a 6th-grade reading level." However, the FDA reacted promptly with a warning letter when a Zoloft advertisement omitted information about the risk of suicidality.

References

- Obach RS, Cox LM, Tremaine LM (2005). "Sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes, monoamine oxidases, and glucuronyl transferases in human: an in vitro study" (free access). Drug Metabolism & Disposition. 33: 262. doi:10.1124/dmd.104.002428.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The sertraline prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Zoloft and generic Sertraline using data from the charts for generic and brand name drugs, see: Verispan (2008-02-18). "Top 200 Generic Drugs by Units in 2007" (PDF). Drug Topics. Retrieved 2008-03-30. and Verispan (2008-02-18). "Top 200 Brand Drugs by Units in 2007" (PDF). Drug Topics. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ Flament MF, Lane RM, Zhu R, Ying Z (1999). "Predictors of an acute antidepressant response to fluoxetine and sertraline". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 14 (5): 259–75. doi:10.1097/00004850-199914050-00001. PMID 10529069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wiley InterScience - Cochrane review: Behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents

- ^ The

BSPS15 criterion identified 28 (21%) of sertraline-treated

patients and 4 (6%) of placebo-treated patients as responders.

The 50% reduction in BSPS criterion identified 47 (35%) of

sertraline-treated patients and 9 (13%) of placebo-treated

patients as responders. Finally, the 50% reduction in MFQ-SP

criterion identified 53 (39%) of sertraline-treated patients and

9 (13%) of placebo-treated patients as responders. Van Ameringen M, Oakman J, Mancini C, Pipe B, Chung H (2004). "Predictors of response in generalized social phobia: effect of age of onset". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24 (1): 42–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000104909.75206.6f. PMID 14709946.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid14709946" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ CGI-Improvement, mean ± SD: Sertraline = 2.3 ± 0.1 Placebo = 2.8 ± 0.1. CGI-Severity, mean ± SD: Change Sertraline = −1.3 ± 0.1; placebo = −1.0 ± 0.1 Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, Sikes CR, Farfel GM (2001). "Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 58 (5): 485–92. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.485. PMID 11343529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid11343529" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - PubMed | The effect of sertraline on cognitive functions in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

- ^ The most complete account of sertraline discovery, targeted at chemists, see: Welch WM (1995). "Discovery and Development of Sertraline". Advances in Medicinal Chemistry. 3: 113–148. doi:10.1016/S1067-5698(06)80005-2.

- Sarges R, Tretter JR, Tenen SS, Weissman A (1973). "5,8-Disubstituted 1-Aminotetralins. A Class of Compounds with a Novel Profile of Central Nervous System Activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (9): 1003–1011. doi:10.1021/jm00267a010. PMID 4795663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - See also: Mullin R (2006). "ACS Award for Team Innovation". Chemical & Engineering News. 84 (5): 45–52.

- A short blurb on the history of sertraline, see: Couzin J (2005). "The brains behind blockbusters". Science. 309 (5735): 728. doi:10.1126/science.309.5735.728. PMID 16051786.

- Healy, David (1999). The Antidepressant Era. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-674-03958-0.

- "Minutes of the 33rd Meeting of Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee on November 19, 1990" (PDF). FDA. 1990. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- See also:Fabre LF, Abuzzahab FS, Amin M, Claghorn JL, Mendels J, Petrie WM, Dubé S, Small JG (1995). "Sertraline safety and efficacy in major depression: a double-blind fixed-dose comparison with placebo". Biol. Psychiatry. 38 (9): 592–602. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(95)00178-8. PMID 8573661.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mant A, Rendle VA, Hall WD; et al. (2004). "Making new choices about antidepressants in Australia: the long view 1975-2002". Med. J. Aust. 181 (7 Suppl): S21–4. PMID 15462638.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Top 10 drugs - 1998". Australian Prescriber. 22: 119. 1999. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- "Top 10 drugs - 2000-01". Australian Prescriber. 24: 136. 2001. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- "Prescribing trends for SSRIs and related antidepressants" (PDF). UK MHRA. 2004. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- Skinner BJ, Rovere M (2007-07-31). "Canada's Drug Price Paradox 2007" (PDF). The Fraser Institute. pp. 21–29. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- "Safety review of antidepressants used by children completed". MHRA. 2003-12-10. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- Boseley, Sarah (2003-12-10). "Drugs for depressed children banned". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- "Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents". MHRA. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- Food and Drug Administration (2007-05-02). "FDA Proposes New Warnings About Suicidal Thinking, Behavior in Young Adults Who Take Antidepressant Medications". Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- Smith, Aaron (2006-07-17). "Pfizer needs more drugs". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R (2008). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (3): 252–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779. PMID 18199864.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - For example, in this study two-thirds of depressed inpatients were treated with sertraline and only one-third with the TCA amitriptyline. Schramm E, van Calker D, Dykierek P, Lieb K, Kech S, Zobel I, Leonhart R, Berger M (2007). "An intensive treatment program of interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy for depressed inpatients: acute and long-term results". Am J Psychiatry. 164 (5): 768–77. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.5.768. PMID 17475736.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lépine JP, Goger J, Blashko C, Probst C, Moles MF, Kosolowski J, Scharfetter B, Lane RM (2000). "A double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of sertraline and clomipramine in outpatients with severe major depression". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 15 (5): 263–71. doi:10.1097/00004850-200015050-00003. PMID 10993128.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ravindran AV, Guelfi JD, Lane RM, Cassano GB (2000). "Treatment of dysthymia with sertraline: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in dysthymic patients without major depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (11): 821–7. PMID 11105734.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thase ME, Fava M, Halbreich U, Kocsis JH, Koran L, Davidson J, Rosenbaum J, Harrison W (1996). "A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial comparing sertraline and imipramine for the treatment of dysthymia". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 53 (9): 777–84. PMID 8792754.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ravindran AV, Anisman H, Merali Z, Charbonneau Y, Telner J, Bialik RJ, Wiens A, Ellis J, Griffiths J (1999). "Treatment of primary dysthymia with group cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy: clinical symptoms and functional impairments". Am J Psychiatry. 156 (10): 1608–17. PMID 10518174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Markowitz JC, Kocsis JH, Bleiberg KL, Christos PJ, Sacks M (2005). "A comparative trial of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for "pure" dysthymic patients". J Affect Disord. 89 (1–3): 167–75. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.001. PMID 16263177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Browne G, Steiner M, Roberts J, Gafni A, Byrne C, Dunn E, Bell B, Mills M, Chalklin L, Wallik D, Kraemer J (2002). "Sertraline and/or interpersonal psychotherapy for patients with dysthymic disorder in primary care: 6-month comparison with longitudinal 2-year follow-up of effectiveness and costs". J Affect Disord. 68 (2–3): 317–30. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00343-3. PMID 12063159.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hoehn-Saric R, Ninan P, Black DW, Stahl S, Greist JH, Lydiard B, McElroy S, Zajecka J, Chapman D, Clary C, Harrison W (2000). "Multicenter double-blind comparison of sertraline and desipramine for concurrent obsessive-compulsive and major depressive disorders". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 57 (1): 76–82. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.76. PMID 10632236.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lepola U, Arató M, Zhu Y, Austin C (2003). "Sertraline versus imipramine treatment of comorbid panic disorder and major depressive disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 (6): 654–62. PMID 12823079.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ekselius L, von Knorring L (1998). "Personality disorder comorbidity with major depression and response to treatment with sertraline or citalopram". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 13 (5): 205–11. doi:10.1097/00004850-199809000-00003. PMID 9817625.

- ^ Reimherr FW, Chouinard G, Cohn CK, Cole JO, Itil TM, LaPierre YD, Masco HL, Mendels J (1990). "Antidepressant efficacy of sertraline: a double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major depression". J Clin Psychiatry. 51 Suppl B: 18–27. PMID 2258378.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lydiard RB, Stahl SM, Hertzman M, Harrison WM (1997). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the effects of sertraline versus amitriptyline in the treatment of major depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (11): 484–91. PMID 9413414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rush AJ, Koran LM, Keller MB, Markowitz JC, Harrison WM, Miceli RJ, Fawcett JA, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, Klein DN, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME (1998). "The treatment of chronic depression, part 1: study design and rationale for evaluating the comparative efficacy of sertraline and imipramine as acute, crossover, continuation, and maintenance phase therapies". J Clin Psychiatry. 59 (11): 589–97. PMID 9862605.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RM, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Markowitz JC, Fawcett JA, Koran LM, Klein DN, Russell JM, Kornstein SG, McCullough JP, Davis SM, Harrison WM (1998). "The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 (11): 598–607. PMID 9862606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller IW, Keitner GI, Schatzberg AF, Klein DN, Thase ME, Rush AJ, Markowitz JC, Schlager DS, Kornstein SG, Davis SM, Harrison WM, Keller MB (1998). "The treatment of chronic depression, part 3: psychosocial functioning before and after treatment with sertraline or imipramine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 (11): 608–19. PMID 9862607.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Koran LM, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, Howland RH, Friedman RA, DeBattista C, Klein D, Kocsis JH, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Rush AJ, Hirschfeld RM, LaVange LM, Keller MB (2001). "Sertraline versus imipramine to prevent relapse in chronic depression". Journal of Affective Disorders. 65 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00272-X. PMID 11426506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Parker G, Roy K, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P (2001). "Assessing the comparative effectiveness of antidepressant therapies: a prospective clinical practice study". J Clin Psychiatry. 62 (2): 117–25. PMID 11247097.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Anderson IM (1998). "SSRIS versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". Depress Anxiety. 7 Suppl 1: 11–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)7:1+<11::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 9597346.

- Hirschfeld RM (1999). "Efficacy of SSRIs and newer antidepressants in severe depression: comparison with TCAs". J Clin Psychiatry. 60 (5): 326–35. PMID 10362442.

- Amsterdam JD (1998). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor efficacy in severe and melancholic depression". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 12 (3 Suppl B): S99–111. PMID 9808081.

- Lydiard RB, Perera P, Batzar E, Clary CM (1999). "From the Bench to the Trench: A Comparison of Sertraline Treatment of Major Depression in Clinical and Research Patient Samples". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1 (5): 154–162. PMC 181082. PMID 15014677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cipriani, A (28 January 2009). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 373 (9665). Elsevier: 746–758. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - Papakostas GI, Fava M (2006). "A metaanalysis of clinical trials comparing moclobemide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 51 (12): 783–90. PMID 17168253.

- Feiger A, Kiev A, Shrivastava RK, Wisselink PG, Wilcox CS (1996). "Nefazodone versus sertraline in outpatients with major depression: focus on efficacy, tolerability, and effects on sexual function and satisfaction". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 Suppl 2: 53–62. PMID 8626364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ventura D, Armstrong EP, Skrepnek GH, Haim Erder M (2007). "Escitalopram versus sertraline in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 23 (2): 245–50. doi:10.1185/030079906X167273. PMID 17288677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kavoussi RJ, Segraves RT, Hughes AR, Ascher JA, Johnston JA (1997). "Double-blind comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline in depressed outpatients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (12): 532–7. PMID 9448656.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - For the review, see:Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS (2005). "Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Ann. Intern. Med. 143 (6): 415–26. PMID 16172440.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cipriani A, Brambilla P, Furukawa T, Geddes J, Gregis M, Hotopf M, Malvini L, Barbui C (2005). "Fluoxetine versus other types of pharmacotherapy for depression". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (4): CD004185. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004185.pub2. PMID 16235353.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mehtonen OP, Søgaard J, Roponen P, Behnke K (2000). "Randomized, double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and sertraline in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Venlafaxine 631 Study Group". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (2): 95–100. PMID 10732656.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Shelton RC, Haman KL, Rapaport MH, Kiev A, Smith WT, Hirschfeld RM, Lydiard RB, Zajecka JM, Dunner DL (2006). "A randomized, double-blind, active-control study of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (11): 1674–81. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n1102. PMID 17196045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wise TN, Sheridan MJ (2000). "Venlafaxine versus sertraline for major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (11): 873–4. PMID 11105744.

- Sir A, D'Souza RF, Uguz S, George T, Vahip S, Hopwood M, Martin AJ, Lam W, Burt T (2005). "Randomized trial of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depression: efficacy and discontinuation symptoms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (10): 1312–20. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1015. PMID 16259546.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Muijsers RB, Plosker GL, Noble S (2002). "Sertraline: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 19 (5): 377–92. PMID 12093324.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, Newhouse P, Krishnan KR, Shiovitz T, Weihs K (2003). "An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression". Am J Psychiatry. 160 (7): 1277–85. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1277. PMID 12832242.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Bernard J. Caroll". Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- Carroll BJ (2004). "Sertraline and the Cheshire cat in geriatric depression". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (4): 759, author reply 759–61. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.759. PMID 15056533.

- Kronig MH, Apter J, Asnis G, Bystritsky A, Curtis G, Ferguson J, Landbloom R, Munjack D, Riesenberg R, Robinson D, Roy-Byrne P, Phillips K, Du Pont IJ. (1999). "Placebo-controlled, multicenter study of sertraline treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (2): 172–176. doi:10.1097/00004714-199904000-00013. PMID 10211919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chouinard G, Goodman W, Greist J, Jenike M, Rasmussen S, White K, Hackett E, Gaffney M, Bick PA (1990). "Results of a double-blind placebo controlled trial of a new serotonin uptake inhibitor, sertraline, in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 26 (3): 279–84. PMID 2274626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greist J, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, Liebowitz M, Lydiard RB, Rasmussen S, White K (1995). "Double-blind parallel comparison of three dosages of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 52 (4): 289–95. PMID 7702445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, Mullin B, Martin A, Spencer T, Faraone SV (2003). "Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1919–28. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1919. PMID 14594734.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Flament MF, Bisserbe JC (1997). "Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparative studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 Suppl 12: 18–22. PMID 9393392.

- Bergeron R, Ravindran AV, Chaput Y, Goldner E, Swinson R, van Ameringen MA, Austin C, Hadrava V (2002). "Sertraline and fluoxetine treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: results of a double-blind, 6-month treatment study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 22 (2): 148–54. doi:10.1097/00004714-200204000-00007. PMID 11910259.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Math SB, Janardhan Reddy YC (07/19/2007). "Issues In The Pharmacological Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: First-Line Treatment Options for OCD". medscape.com. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Blier P, Habib R, Flament MF (2006). "Pharmacotherapies in the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder" (PDF). Can J Psychiatry. 51 (7): 417–30. PMID 16838823.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ninan PT, Koran LM, Kiev A, Davidson JR, Rasmussen SA, Zajecka JM, Robinson DG, Crits-Christoph P, Mandel FS, Austin C (2006). "High-dose sertraline strategy for nonresponders to acute treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter double-blind trial". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (1): 15–22. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0103. PMID 16426083.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard B (1995). "A 1 year double-blind placebo-controlled fixed dose study of sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (2): 57–65. doi:10.1097/00004850-199506000-00001. PMID 7673657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rasmussen S, Hackett E, DuBoff E, Greist J, Halaris A, Koran LM, Liebowitz M, Lydiard RB, McElroy S, Mendels J, O'Connor K (1997). "A 2-year study of sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 12 (6): 309–16. doi:10.1097/00004850-199711000-00003. PMID 9547132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Koran LM, Hackett E, Rubin A, Wolkow R, Robinson D (2002). "Efficacy of sertraline in the long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.88. PMID 11772695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team (2004). "Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 292 (16): 1969–76. doi:10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. PMID 15507582.

- Sousa MB, Isolan LR, Oliveira RR, Manfro GG, Cordioli AV (2006). "A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (7): 1133–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0717. PMID 16889458.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, García-Ruiz PJ (2001). "Pharmacological options for the treatment of Tourette's disorder". Drugs. 61 (15): 2207–20. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161150-00005. PMID 11772131.

- Hauser RA, Zesiewicz TA (1995). "Sertraline-induced exacerbation of tics in Tourette's syndrome". Mov. Disord. 10 (5): 682–4. doi:10.1002/mds.870100529. PMID 8552129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Review: Hirschfeld RM (2000). "Sertraline in the treatment of anxiety disorders". Depress Anxiety. 11 (4): 139–57. doi:10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<139::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 10945134.

- ^ Meta-analysis: Clayton AH, Stewart RS, Fayyad R, Clary CM (2006). "Sex differences in clinical presentation and response in panic disorder: pooled data from sertraline treatment studies". Arch Womens Ment Health. 9 (3): 151–7. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0111-y. PMID 16292466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pollack MH, Rapaport MH, Clary CM, Mardekian J, Wolkow R (2000). "Sertraline treatment of panic disorder: response in patients at risk for poor outcome". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (12): 922–7. PMID 11206597.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rapaport MH, Pollack MH, Clary CM, Mardekian J, Wolkow R (2001). "Panic disorder and response to sertraline: the effect of previous treatment with benzodiazepines". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 21 (1): 104–7. doi:10.1097/00004714-200102000-00019. PMID 11199932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bandelow B, Behnke K, Lenoir S, Hendriks GJ, Alkin T, Goebel C, Clary CM (2004). "Sertraline versus paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: an acute, double-blind noninferiority comparison". J Clin Psychiatry. 65 (3): 405–13. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0317. PMID 15096081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fiseković S, Loga-Zec S (2005). "Sertraline and alprazolam in the treatment of panic desorder [sic]". Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 5 (2): 78–81. PMID 16053461.

- ^ Rapaport MH, Wolkow R, Rubin A, Hackett E, Pollack M, Ota KY (2001). "Sertraline treatment of panic disorder: results of a long-term study". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 104 (4): 289–98. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00263.x. PMID 11722304.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Review: Davidson JR (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder: what does the evidence tell us?". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 12: 20–6. PMID 17092192.

- ^ Liebowitz MR, DeMartinis NA, Weihs K, Londborg PD, Smith WT, Chung H, Fayyad R, Clary CM (2003). "Efficacy of sertraline in severe generalized social anxiety disorder: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 (7): 785–92. PMID 12934979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Connor KM, Davidson JR, Chung H, Yang R, Clary CM (2006). "Multidimensional effects of sertraline in social anxiety disorder". Depress Anxiety. 23 (1): 6–10. doi:10.1002/da.20086. PMID 16216019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blomhoff S, Haug TT, Hellström K, Holme I, Humble M, Madsbu HP, Wold JE (2001). "Randomised controlled general practice trial of sertraline, exposure therapy and combined treatment in generalised social phobia". Br J Psychiatry. 179: 23–30. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.1.23. PMID 11435264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yonkers KA, Halbreich U, Freeman E, Brown C, Endicott J, Frank E, Parry B, Pearlstein T, Severino S, Stout A, Stone A, Harrison W. (1997). "Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment. A randomized controlled trial. Sertraline Premenstrual Dysphoric Collaborative Study Group". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 278 (12): 983–988. doi:10.1001/jama.278.12.983. PMID 9307345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Review: Pearlstein T (2002). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: the emerging gold standard?". Drugs. 62 (13): 1869–85. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262130-00004. PMID 12215058.

- Review: Ackermann RT, Williams JW (2002). "Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care: an evidence-based review". J Gen Intern Med. 17 (4): 293–301. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10350.x. PMC 1495030. PMID 11972726.

- ^ Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M, Xiao S (2004). "Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (2): 343–51. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.343. PMID 14754784.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M (1999). "Differential response to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized controlled trial". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 56 (10): 932–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.932. PMID 10530636.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jermain DM, Preece CK, Sykes RL, Kuehl TJ, Sulak PJ (1999). "Luteal phase sertraline treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study". Arch Fam Med. 8 (4): 328–32. doi:10.1001/archfami.8.4.328. PMID 10418540.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers KA, Freeman E, Stout AL, Cohen L (2002). "Efficacy of intermittent, luteal phase sertraline treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Obstet Gynecol. 100 (6): 1219–29. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02326-8. PMID 12468166.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, Farfel GM, Gillespie JA (2006). "Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: efficacy of 3 dosing strategies". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 (10): 1624–32. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n1020. PMID 17107257.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brady K, Pearlstein T, Asnis GM, Baker D, Rothbaum B, Sikes CR, Farfel GM (2000). "Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 283 (14): 1837–44. doi:10.1001/jama.283.14.1837. PMID 10770145.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Londborg PD, Hegel MT, Goldstein S, Goldstein D, Himmelhoch JM, Maddock R, Patterson WM, Rausch J, Farfel GM (2001). "Sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of 24 weeks of open-label continuation treatment". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 (5): 325–31. PMID 11411812.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis LL, Frazier EC, Williford RB, Newell JM (2006). "Long-term pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder". CNS Drugs. 20 (6): 465–76. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620060-00003. PMID 16734498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Davidson J, Pearlstein T, Londborg P, Brady KT, Rothbaum B, Bell J, Maddock R, Hegel MT, Farfel G (2001). "Efficacy of sertraline in preventing relapse of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of a 28-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (12): 1974–81. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1974. PMID 11729012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Davidson J, Rothbaum BO, Tucker P, Asnis G, Benattia I, Musgnung JJ (2006). "Venlafaxine extended release in posttraumatic stress disorder: a sertraline- and placebo-controlled study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 26 (3): 259–67. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000222514.71390.c1. PMID 16702890.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tucker P, Potter-Kimball R, Wyatt DB, Parker DE, Burgin C, Jones DE, Masters BK (2003). "Can physiologic assessment and side effects tease out differences in PTSD trials? A double-blind comparison of citalopram, sertraline, and placebo". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 37 (3): 135–49. PMID 14608246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McRae AL, Brady KT, Mellman TA, Sonne SC, Killeen TK, Timmerman MA, Bayles-Dazet W (2004). "Comparison of nefazodone and sertraline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder". Depression and Anxiety. 19 (3): 190–6. doi:10.1002/da.20008. PMID 15129422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zohar J, Amital D, Miodownik C, Kotler M, Bleich A, Lane RM, Austin C (2002). "Double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of sertraline in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 22 (2): 190–5. doi:10.1097/00004714-200204000-00013. PMID 11910265.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Friedman MJ, Marmar CR, Baker DG, Sikes CR, Farfel GM (2007). "Randomized, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder in a Department of Veterans Affairs setting". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 68 (5): 711–20. doi:10.4088/JCP.v68n0508. PMID 17503980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Allgulander C, Dahl AA, Austin C, Morris PL, Sogaard JA, Fayyad R, Kutcher SP, Clary CM. (2004). "Efficacy of sertraline in a 12-week trial for generalized anxiety disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (9): 1642–1649. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1642. PMID 15337655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brawman-Mintzer O, Knapp RG, Rynn M, Carter RE, Rickels K (2006). "Sertraline treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 (6): 874–81. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0603. PMID 16848646.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI. (2000). "Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (6): 1004–1006. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.1004. PMID 10831483.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leombruni P, Pierò A, Lavagnino L, Brustolin A, Campisi S, Fassino S (2008). "A randomized, double-blind trial comparing sertraline and fluoxetine 6-month treatment in obese patients with Binge Eating Disorder". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 32 (6): 1599. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.06.005. PMID 18598735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - O'Reardon JP, Allison KC, Martino NS, Lundgren JD, Heo M, Stunkard AJ (2006). "A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of night eating syndrome". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (5): 893–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.893. PMID 16648332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Milano W, Petrella C, Sabatino C, Capasso A (2004). "Treatment of bulimia nervosa with sertraline: a randomized controlled trial". Adv Ther. 21 (4): 232–7. doi:10.1007/BF02850155. PMID 15605617.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McMahon CG. (1998). "Treatment of premature ejaculation with sertraline hydrochloride: a single-blind placebo controlled crossover study". The Journal of Urology. 159 (6): 1935–1938. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63201-4. PMID 9598491.

- Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B (1998). "Effect of SSRI antidepressants on ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 18 (4): 274–81. doi:10.1097/00004714-199808000-00004. PMID 9690692.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Waldinger MD (2007). "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". Urol. Clin. North Am. 34 (4): 591–9, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B (2004). "On-demand treatment of premature ejaculation with clomipramine and paroxetine: a randomized, double-blind fixed-dose study with stopwatch assessment". Eur. Urol. 46 (4): 510–5, discussion 516. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.05.005. PMID 15363569.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abdel-Hamid IA, El Naggar EA, El Gilany AH (2001). "Assessment of as needed use of pharmacotherapy and the pause-squeeze technique in premature ejaculation". Int. J. Impot. Res. 13 (1): 41–5. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900630. PMID 11313839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang WF, Wang Y, Minhas S, Ralph DJ (2007). "Can sildenafil treat primary premature ejaculation? A prospective clinical study". Int. J. Urol. 14 (4): 331–5. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01606.x. PMID 17470165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grubb BP, Samoil D, Kosinski D, Kip K, Brewster P. (1994). "Use of sertraline hydrochloride in the treatment of refractory neurocardiogenic syncope in children and adolescents". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 24 (2): 490–494. PMID 8034887.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lenk MK, Alehan D, Ozme S, Celiker A, Ozer S (1997). "Vasovagal syncope: asystole provoked by head-up tilt testing under sertraline therapy". Turk. J. Pediatr. 39 (4): 573–7. PMID 9433163.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lenk M, Alehan D, Ozme S, Celiker A, Ozer S (1997). "The role of serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in preventing recurrent unexplained childhood syncope -- a preliminary report". Eur. J. Pediatr. 156 (10): 747–50. doi:10.1007/s004310050704. PMID 9365060.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tandan T, Giuffre M, Sheldon R (1997). "Exacerbations of neurally mediated syncope associated with sertraline". Lancet. 349 (9059): 1145–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63021-8. PMID 9113018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Zoloft Prescribing Information for the U.S." (PDF). Pfizer. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M, Espinós JC, Rosinach M, Forné M, Salas A, Viver JM (2007). "Drug consumption and the risk of microscopic colitis". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102 (2): 324–30. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00902.x. PMID 17100977.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Olivera AO (1997). "Sertraline and akathisia: spontaneous resolution". Biol. Psychiatry. 41 (2): 241–2. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00384-8. PMID 9018398.

- Review:Leo RJ (1996). "Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 (10): 449–54. PMID 8909330.

- Lauterbach EC, Meyer JM, Simpson GM (1997). "Clinical manifestations of dystonia and dyskinesia after SSRI administration". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (9): 403–4. PMID 9378692.