| Revision as of 08:00, 22 January 2006 edit81.151.241.161 (talk) →Further reading← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:57, 8 February 2006 edit undo207.178.156.190 (talk) →Compare withNext edit → | ||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] (related in some theories to the idea of ancient people using ] ]) | * ] (related in some theories to the idea of ancient people using ] ]) | ||

| * ] (role-playing game based on supernatural events involving Ley Lines) | |||

| <!-- see the reconstruction part and the TLC link @ article--> | <!-- see the reconstruction part and the TLC link @ article--> | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 8 February 2006

Ley lines are alignments of a number of places of geographical interest, such as ancient megaliths. Their existence was first suggested in 1921 by the amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins, whose book The Old Straight Track first brought the phenomenon to the attention of the wider public.

The existence of these apparently remarkable alignments between sites is easily demonstrated. However, the causes of these alignments are disputed. There are three major schools of thought:

- Anthropological: According to proponents of some ley line theories, the early inhabitants of Britain determined the placement of Stonehenge and various other megalith structures, buildings, monuments, or mounds according to a system of these lines, which often pass through, or near, several such structures. Some of these theories believe leys to have had some astronomical significance, or to relate to traditional religious beliefs associated with these sites. Others simply see leys as marking trade routes.

- New Age: Some have claimed that these points resonate a special psychic energy named earth radiation. These theories often include elements such as geomancy, dowsing or UFOs.

- Skeptical: Skeptics of these ley line theories believe that they belong in the realms of pseudoscience. Most skeptics believe that ley lines can be explained completely by chance alignments of random points that appear intuitively unlikely, but can be demonstrated to be unsurprising coincidences. Some skeptics are investigating if these points have electrical or magnetic forces associated with them.

The anthropological approach: Alfred Watkins and The Old Straight Track

The concept of ley lines was first propounded by Alfred Watkins. On June 30, 1921, Watkins visited Blackwardine in Herefordshire, and went riding around near some hills in the vicinity of Bredwardine when he noted many of the footpaths therein seemed to connect one hilltop to another in a straight line. He was studying a map when he noticed that a number of significant places were in alignment. "The whole thing came to me in a flash," he would later explain to his son. Some people have portrayed this as being some sort of mystical experience. However William Henry Black gave a talk entitled Boundaries and Landmarks to the British Archaeological Association in Hereford in September 1870. Here he speculated that "Monuments exist marking grand geometrical lines which cover the whole of Western Europe". It is possible that Watkins' experience stemmed from some half-recollected memories of an account of that presentation.

Watkins believed that in ancient times, when Britain had been far more densely forested, the country had been crisscrossed by a network of straight-line travel routes, with prominent features of the landscape being used as navigation points. This chance observation led him onto a line of theorising which he made public at a meeting of the Woolhope Club of Hereford in September 1921. His work referred back to G. H. Piper's paper presented to the Woolhope Club in 1882 which noted that

- "A line drawn from the Skirrid-fawr mountain northwards to Arthur's Stone would pass over the camp and southern most point of Hatterill Hill, Oldcastle, Longtown Castle, and Urishay and Snodhill castles."

The ancient surveyors who supposedly made the lines were given the name "dodmen".

Watkins published his ideas in the books Early British Trackways and The Old Straight Track; however, they were received with skepticism in the archaeological community. The archaeologist O. G. S. Crawford refused to accept advertisements for the latter in the journal Antiquity, and most archaeologists since then have continued to be dismissive of Watkins' ideas.

The discovery of the Nazca lines, which demonstrated easily observable man-made long straight tracks on the plains of Peru, caused a resurgence of interest in anthropological explanations of ley lines in the 1970s.

Nevertheless Watkins' contribution has helped stimulate new approaches in archaeology: Alexander Thom has offered a detailed analysis of megalithic alignments specifically geared to providing evidence of complex astronomical information being incorporated in such sites as Stonehenge. Yet he avoids using the term ley line which has become too much identified with the New Age theories and Ufology.

The New Age approach: magical and holy lines

Watkins' theories have been adapted by later writers. Some of his ideas were taken up by the occultist Dion Fortune who featured them in her 1936 novel The Goat-footed God. Since then, ley lines have become the subject of many magical and mystical theories.

The two British dowsers, Captain Robert Boothby and Reginald Smith of the British Museum have linked the appearance of ley-lines with underground streams, and magnetic currents. Ley-spotter / Dowser Underwood conducted various investigations and claimed that crossings of 'negative' water lines and positive aquastats explain why certain sites were chosen as holy. He found so many of these 'double lines' on sacred sites that he named them 'holy lines.'

Two German Nazi researchers Wilhelm Teudt and Josef Heinsch have also claimed that ancient Teutonic peoples contributed to the construction of a network of astronomical lines, called “Holy lines” (Heilige Linien), which could be mapped onto the geographical layout of ancient or sacred sites. Teudt located the Teutoburger Wald district in Lower Saxony, centered around the dramatic rock formation called Die Externsteine as the centre of Germany.

By the 1960s, the ideas of a landscape crossed with straight lines had become conflated with ideas from various geomantic traditions; mapping ley lines, according to New Age geomancers, can foster "harmony with the Earth" or reveal pre-historic trade routes. John Michell's writing can be seen as an example of this. He has referred to the whole face of China being heavily landscaped in accordance with the laws of Feng Shui. Michell has claimed that Neolithic peoples recognised that the harmony of society depend on the harmony of the earth force. And so in China, ancient Greece and Scotland men built their temples where the forces of the earth were most powerful.

The skeptical approach: chance alignments

Some skeptics have suggested that ley lines are a product of human fancy. Watkins' discovery happened at a time when Ordnance Survey maps were being marketed for the leisure market, making them reasonably easy and cheap to obtain; this may have been a contributing factor to the popularity of ley line theories.

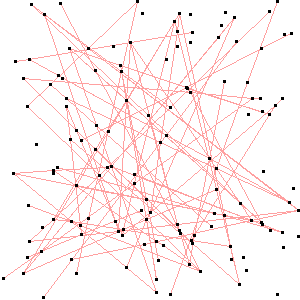

One suggestion is that thanks to the high density of historic and prehistoric sites in Britain and other parts of Europe, that finding straight lines that "connect" sites (usually selected to make them "fit") is trivial, and may be easily ascribed to coincidence. The diagram to the right shows an example of lines that pass very near to a set of random points: for all practical purposes, they can be regarded as "exact" alignments. Naturally, it is debated whether all ley lines can be accounted for in this way, or whether there are more ley lines than would be expected by chance. (For a mathematical treatment of this topic, see alignments of random points).

Regarding the trade route theories, skeptics point out that straight lines do not make ideal roads in all circumstances, particularly where they ignore topography and require users to march up and down hills or mountains, or to cross rivers at points where there is no ford or bridge.

Are alignments and ley lines the same thing?

The existence of the observed alignments is not controversial. Both believers in magical and ancient theories of ley lines and skeptics of these theories agree that these alignments exist between megaliths and ancient sites.

Most skeptics believe that their null hypothesis of ley-line-like alignments being due to random chance is consistent with all known evidence. They believe that this removes the need to explain these alignments in any other way. Some Chaos Magicians have views consistent with this, and claim this is in accord with their generative view of chance. However other proponents of ley line theories believe that further theories are needed to explain the observed evidence. See hypothesis testing, falsifiability and Occam's razor for more on these topics.

For discussing the arguments for and against the chance presence of ley line alignments it is useful to define the term "alignment" precisely enough to reason about it. One precise definition which expresses the generally accepted meaning of Watkins' ley lines defines an alignment as:

- a set of points, chosen from a given set of landmark points, all of which lie within at least an arc of 1/4 degree.

Watkins remarked that if this is accepted as the degree of error, then

- "if only three accidentally placed points are on the sheet, the chance of a three point alignment is 1 in 720."

- "But this chance by accidental coincidence increases so rapidly in geometric progression with each point added that if ten mark-points are distributed haphazard on a sheet of paper, there is an average probability that there will be one three-point alignment, while if only two more points are added to make twelve points, there is a probability of two three-point alignments."

- "It is clear that a three-point alignment must not be accepted as proof of a ley by itself, as a fair number of other eligible points are usually present."

- "A ley should not be taken as proved with less than four good mark-points. Three good points with several others of less value like cross roads and coinciding tracks maybe sufficient."

- The Leyhunter's Manual (page 88), 1927

One should also bear in mind that lines and points on a map cover wide areas on the ground. With 1:63360 (1-inch-to-the-mile) maps a 1/100-inch (1/4 mm) wide line represents a path over 50 feet (15 m) across. And in travelling across a sheet, an angle of 1/4 degree encompasses something like an additional 600 feet (200 m).

Controversy

The demonstration of the plausibility of the current evidence under the null hypothesis is not a formal disproof of ley line claims. However, it does make skeptics likely to consider ley line theories as unsupported by the current evidence.

Most skeptics would be willing to reconsider the hypothesis of ley lines if there was non-anecdotal evidence of physical, geomagnetic or archeological features that actually lay along the paths of ley lines. Skeptics believe that no such convincing evidence has been presented.

There is a broad range of beliefs about and theories of ley lines, many of which are not falsifiable. Some people find ley lines compatible with a scientific approach, but much of the literature is written by people who are indifferent to or actively oppose such an approach.

Scientific investigation

According to data obtained by investigators of ley line theories, some ley lines points possess higher magnetic energy than the average geomagnetic intensity. This has been investigated and published about in sources such as "Places of power" (Paul Devereux; Blandford Press, 1990) and "Lodestone Compass: Chinese or Olmec Primacy?" (John B. Carlson; Science, 1975) among other sources.

Theories of magnetic interaction at ley line points suggest to some observers that these points were used to induct energy. Some geomantic researchers have investigated this phenomenon by studying telluric currents, geomagnetism, and the Schumann resonance (among other physical phenomena). Current data is inconclusive.

See also

- List of ley lines

- Earth radiation

- Pattern recognition

- Confirmation bias

- Topology

- Geoglyphs

- Archaeoastronomy

- Archaeogeodesy

- Church lines

- Cursus monument

- Leylines (computer game)

Compare with

- Earth mysteries

- The Bible Code

- Feng shui

- Ark of the Covenant (related in some theories to the idea of ancient people using electromagnetic energy)

- Rifts (role-playing game based on supernatural events involving Ley Lines)

Further reading

- Alfred Watkins, Early British Trackways (1922)

- Alfred Watkins, The Old Straight Track: Its Mounds, Beacons, Moats, Sites and Mark Stones (1925); reprinted as ISBN 0349137072

- Alfred Watkins, The Ley Hunter's Manual (1927)

- Tony Wedd, Skyways and Landmarks (1961)

- Williamson, T. and Bellamy, L., Ley Lines in Question. (1983)

- Tom Graves, Needles of Stone (1978) -- mixes ley lines and acupuncture; online edition at

- Paul Broadhurst & Hamish Miller The Sun And The Serpent (1989, 1990 (paperback), 1991, 1994, 2003 (paperback))

External links

- Ley lines, the earth's energy channels

- Energy Lines: Earth Chakra Correspondences

- A ley line map

- http://www.magonia.demon.co.uk/arc/80/leyhistory.html

- The Ley Line Mystery

- The Society of Ley Hunters

- Ley Lines and Coincidence: discussion and computer simulation results

- Skeptic's Dictionary entry on Ley Lines

- GIS and Remote sensing site

- Ley lines, dead and buried by Danny Sullivan (Adobe pdf format)

- An excerpt from The New Ley Hunter's Guide by Paul Devereux

- Moonraking: What does it all mean?

Data sources

- The Megalithic Map (which does not take a position on this issue, but does illustrate the distribution of major megaliths in the UK)

- Megalithia, a similar website with grid references for over 1,400 sites

- GENUKI Parish Database, including grid references for over 14,000 UK churches and register offices

- The Gazetteer of British Place Names with over 50,000 entries