| Revision as of 22:53, 13 February 2006 view source160.39.209.191 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:15, 13 February 2006 view source Matia.gr (talk | contribs)4,184 editsm →Service in the Ottoman ArmyNext edit → | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| Born in ], Skanderbeg was a descendant of the Kastriotis, who were one of the principal families in what was called then, Arberia (today Albania). | Born in ], Skanderbeg was a descendant of the Kastriotis, who were one of the principal families in what was called then, Arberia (today Albania). | ||

| According to ], his father John Kastrioti was a hereditary prince of a small district of Epirus or Albania. He was obliged by the Ottoman Empire to pay tribute and to ensure the fidelity of local rulers, George Kastrioti and his three brothers were taken by the Sultan to his court. He attended military school and led many battles for the Ottoman Empire to victory. For his military victories, he received the title ''Arnavut İskender ]'', (]: ''Skënderbeu Shqiptari'', ]: ''Skenderbeg, the Albanian''). In ] and Albanian this title means ''Lord Alexander'', comparing Kastrioti's military brilliance to that of ]). | |||

| He earned distinction as an officer in several Ottoman campaigns both in ] and in ], and the Sultan appointed him to the rank of General by giving him a cavalry force of 5,000 men. Some sources claim that he maintained secret links with ], ], ] of ], and ] of ]. | He earned distinction as an officer in several Ottoman campaigns both in ] and in ], and the Sultan appointed him to the rank of General by giving him a cavalry force of 5,000 men. Some sources claim that he maintained secret links with ], ], ] of ], and ] of ]. | ||

Revision as of 23:15, 13 February 2006

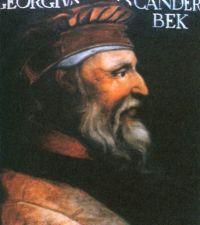

Gjergj Kastrioti (George Kastrioti) (1405 - January 17 1468), better known as Skenderbeg, is the most prominent figure in the history of Albania. Although he fought in the service of the Ottoman Empire, he switched sides and came back to his native land to successfully defend Albania against the Ottomans until the time of his death.

In English, his names have variously been spelled: Gjergj, George, Giorgio; Kastrioti, Castrioti, Castriot, Kastriot; Skanderbeg, Scanderbeg, Skenderbeg, or Scander-Begh.

Biography

Service in the Ottoman Army

Born in Krujë, Skanderbeg was a descendant of the Kastriotis, who were one of the principal families in what was called then, Arberia (today Albania).

According to Gibbon, his father John Kastrioti was a hereditary prince of a small district of Epirus or Albania. He was obliged by the Ottoman Empire to pay tribute and to ensure the fidelity of local rulers, George Kastrioti and his three brothers were taken by the Sultan to his court. He attended military school and led many battles for the Ottoman Empire to victory. For his military victories, he received the title Arnavut İskender Bey, (Albanian: Skënderbeu Shqiptari, English: Skenderbeg, the Albanian). In Turkish and Albanian this title means Lord Alexander, comparing Kastrioti's military brilliance to that of Alexander the Great).

He earned distinction as an officer in several Ottoman campaigns both in Asia Minor and in Europe, and the Sultan appointed him to the rank of General by giving him a cavalry force of 5,000 men. Some sources claim that he maintained secret links with Ragusa, Venice, Ladislaus V of Hungary, and Alfonso I of Naples.

Fighting for the freedom of Albania

In 1443 Skanderbeg saw his opportunity to rebel during a battle against the Hungarians led by John Hunyadi in Niš. He switched sides along with 300 other Albanians serving in the Ottoman army. After a long trek to Albania he eventually captured Krujë by forging a letter from the Sultan which claimed to grant him control of the territory. After capturing the castle, he raised the Albanian flag above the castle and reportedly pronounced: "I have not brought you liberty, I found it here, among you."

Following the capture of Krujë, Skanderbeg managed to bring together all the Albanian princes in the town of Lezhë (see League of Lezhë, 1444) and unite them under his command against the Ottomans. He fought a guerrilla war against the opposing armies by using the mountainous terrain to his advantage. Skenderbeg continues his resistance against the Ottoman forces, arguably the most powerful army of the time, with a force rarely exceeding 20,000.

Although it is commonly believed that Skanderbeg took part in the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448, he actually never arrived. He and his army were en route to reinforce the mainly Hungarian army of John Hunyadi, but the Albanians were intercepted and defeated by Đurađ Branković of Serbia. Although Hunyadi was defeated in the campaign, Hungary resisted the Ottoman campaigns during his lifetime.

In June 1450, an Ottoman army numbering approximately 150,000 men led by Sultan Murad II himself laid siege to Krujë. Leaving a protective garrison of 1,500 men under one of his most trusted lieutenants, Vrana Konti (also know as Kont Urani), Skenderbeg harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë and attacked the supply caravans of the sultan's army. By September the Ottoman camp was in disarray as morale sank and disease ran rampant. Grudgingly, Murad acknowledged the castle of Krujë would not fall by strength of arms, and he lifted the siege and made his way to Edirne. Soon thereafter in the winter of 1450-51, Murad died in Edirne and was succeeded by his son Mehmed II.

For the next five years Albania was allowed some respite as the new sultan set out to conquer the last vestiges of the Byzantine Empire. The first test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg came in 1455 during the Siege of Berat, and would end in the most disastrous defeat Skanderbeg would suffer. Skanderbeg had sieged the town's castle for months, causing the demoralised Turkish officer in charge of the castle to promise his surrender. At that point Skanderbeg relaxed the grip and left the siege location. He left behind one of his generals and half of his cavalry at the bank of the river Osam to finalize the surrender.

The Ottomans saw this moment as an opportunity for attack. They sent a large cavalry force from Fushe in Kosovo to Berat as reinforcements. The Albanian forces had become overconfident and had been lulled into a false sense of security. The Ottomans caught the Albanian cavalry by surprise while they were resting in the shores of the Osam. Almost all the 5,000 Albanian cavalry laying siege to Berat were massacred. When Skanderbeg made it to the battlefield, everything was over; the Ottoman cavalry had already left for Anatolia. This was the worst military defeat that Skanderbeg suffered.

In 1457, an Ottoman army numbering approximately 80,000 men invaded Albania with the hope of destroying Albanian resistance once and for all; this army was led by Isa beg Evrenoz, the only commander to have defeated Skanderbeg in battle, and Hamza Kastrioti, Skanderbeg’s nephew. After wreaking much damage to the countryside, the Ottoman army set up camp at the Ujebardha field (literally translated as "Whitewater"), halfway between Lezhë and Krujë. After having evaded the enemy for months, Skanderbeg attacked there with a force not exceeding 15,000 men and defeated the Ottomans in September.

In 1461 Skanderbeg launched a successful campaign against the Angevin noblemen and their allies who sought to destabilize King Ferdinand I of Naples. After securing the Neapolitan kingdom, a crucial ally in his struggle, he returned home. In 1464 Skanderbeg fought and defeated Ballaban Badera, an Albanian renegade who had captured a large number of Albanian army commanders, including Moisi Arianit Golemi, a cavalry commander; Vladan Giurica, the chief army economist; Muzaka of Angelina, a nephew of Skanderbeg, and 18 other noblemen and army captains. These men, after they were captured, were sent immediately to Istanbul and tortured for fifteen days. Skanderbeg’s pleas to have these men back, by either ransom or prisoner exchange, failed.

In 1466 Sultan Mehmed II personally led an army into Albania and laid siege to Krujë as his father had attempted sixteen years earlier. The town was defended by a garrison of 4,400 men, led by Prince Tanush Topia. After several months, Mehmed, like Murad II, saw that seizing Krujë by force of arms was impossible for him to accomplish. Shamed, he left the siege to return to Istanbul. However, he left a force of 40,000 men under Ballaban Pasha to maintain the siege, even building a castle in central Albania, which he named El-basan (the modern Elbasan), to support the siege. This second siege was eventually broken by Skanderbeg, resulting in the death of Ballaban Pasha from firearms.

A few months later in 1467, Mehmed, frustrated by his inability to subdue Albania, again led the largest army of its time into Albania. Krujë was besieged for a third time, but on a much grander scale. While a contingent kept the city and its forces pinned down, Ottoman armies came pouring in from Bosnia, Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece with the aim of keeping the whole country surrounded, thereby strangling Skanderbeg’s supply routes and limiting his mobility. During this conflict, Skanderbeg fell ill with malaria in the Venetian-controlled city of Lezhë, and died on January 17 1468, just as the army under the leadership of Leke Dukagjini defeated the Ottoman force in Shkodër.

The Albanian resistance went on after the death of Skanderbeg for an additional ten years under the leadership of Dukagjini. In 1478, the fourth siege of Krujë finally proved successful for the Ottomans; demoralized and severely weakened by hunger and lack of supplies from the year-long siege, the defenders surrendered to Mehmed, who had promised them to leave unharmed in exchange. As the Albanians were walking away with their families, however, the Ottomans reneged on this promise, killing the men and enslaving the women and children. A year later the Ottoman forces captured Venetian-controlled Shkodër, the last Albanian castle to fall to the Ottomans; Albanian resistance continued sporadically until around 1500.

After death

Following his death in 1468, Albanian forces continued to resist for another 12 years, though with only moderate success and no great victories. Without Skenderbeg at their lead, their allegiences faltered and splintered until they were forced into submission. Following this, most of its population converted to Islam. Albania remained a part of the Ottoman Empire until the early 1900s, never again posing a serious threat to the Ottomans.

Effects on the Ottoman expansion

The Ottoman Empire's expansion was ground to a halt during the timeframe in which Skenderbeg and his Albanian forces resisted. He has been credited with being the main reason for delaying Ottoman expansion into western Europe, giving Vienna time to better prepare for the Ottoman arrival. This is not entirely true. While the Albanian resistance certainly played a vital role in this, it was one piece of numerous events that played out in the mid-15th century. Much credit must also go to the successful resistance mounted by Vlad III Dracula in Wallachia, as well as the defeats inflicted upon the Ottomans by Hunyadi and his Hungarian forces.

Papal relations

Skanderbeg's military successes evoked a good deal of interest and admiration from the Papal States, Venice, and Naples, themselves threatened by the growing Ottoman power across the Adriatic Sea. Skanderbeg managed to arrange for support in the form of money, supplies, and occasionally troops from all three states through his diplomatic skill. One of his most powerful and consistent supporters was Alfonso the Magnanimous, the king of Aragon and Naples, who decided to take Skanderbeg under his protection as a vassal in 1451, shortly after the latter had scored his second victory against Murad II. In addition to financial assistance, the King of Naples supplied the Albanian leader with troops, military equipment, and sanctuary for himself and his family if such a need should arise. As an active defender of the Christian cause in the Balkans, Skanderbeg was also closely involved with the politics of four Popes, including Pope Pius II.

Profoundly shaken by the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Pius II tried to organize a new crusade against the Ottoman Turks, and to that end he did his best to come to Skanderbeg's aid, as his predecessors Pope Nicholas V and Pope Calixtus III had done before him. This policy was continued by his successor, Pope Paul II. They gave him the title Athleta Christi, or Champion of Christ.

Skanderbeg's 25-year resistance against the Ottoman Empire succeeded in helping protect the Italian peninsula from invasion by the Ottoman Turks.

Legacy

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

During his reign Skanderbeg issued many laws (census of the population, tax collecting etc) based on Roman and Byzantine law.

When the Ottomans found the grave of Skanderbeg in Saint Nicholas church of Lezhë, they opened it and made amulets of his bones, believing that these would confer bravery on the wearer.

Skanderbeg's posthumous fame was not confined to his own country. Voltaire thought the Byzantine Empire would have survived had it possessed a leader of his quality. A number of poets and composers have also drawn inspiration from his military career. The French 16th century poet Ronsard wrote a poem about him, as did the 19th century American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Antonio Vivaldi composed an opera entitled Scanderbeg.

Skanderbeg today is the national hero of Albania. Many museums and monuments, such as the Skanderbeg Museum next to the castle in Krujë, are raised in his honor around Albania and in the predominantly Albanian-populated Kosovo. Skanderbeg's struggle against the Ottoman Empire became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.

In Arbëresh poems he is not only the defender of their home country, but also the defender of Christianity. For the Albanians in Albania, a large majority of whom are Muslims, Skanderbeg is a national argument proving Albania's cultural affinity to Europe. Many have argued he was Muslim himself, although he was not. He had converted while held captive in Anatolia, but later reverted back to Christianity upon his escape.

Seal of Skanderbeg

A seal, that is assumed to be a seal of Skanderbeg, has been kept in Denmark since it was discovered in 1634. It was bought by the National Museum in 1839. The seal is clearly an 17th c. fake produced by someone trying to promote himself as Skenderbegs discendant. This is visible from the general outlook, shape of the seal, type of letters and from the heraldic concept. Therefore it is ilusional interpreting its importance. According to the intepretation of the symbols and inscriptions on the seal as they have been studied and analysed by Danish scholars, the seal is made of brass, is 6 cm in length and weighs 280 g. The inscription is in Greek and reads Alexander (Skender) is an Emperor and a King. Emperor of the Romaic nation (Greeks) and King of the Turks, the Albanians, the Serbs and the Bulgars. It naturally follows the inscription is laterally reversed. It is possible that the seal was made after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, since Skanderbeg is referred to as an Emperor of the Byzantines. The double eagle in the center of the seal is derived from the eagle of the Byzantine emperor, and this fact is also the most agreed upon among educated Albanians. Some claim it is a famous ancient Illyrian symbol. This seal is the origin of the flag of modern Albania. Furthermore, Skanderbeg never was a King of the Serbs or the Bulgars. It is possible the seal was 'designed' while Skanderbeg was organising a crusade against the Ottomans or that it was manufactured when Skanderbeg served as a vassal to the King of Naples. It is also possible the seal was commissioned by the family of Skanderbeg some time in the 16th century, or even that it is a fake from the 15th or 16th century.

Descendants

Skanderbeg's family later took refuge in southern Italy, as the Turkish pressure became too much. They obtained a feudal fief, the Duchy of San Pietro di Galatina. An illegitimate branch of that family lives onwards in south Italy, having used the name Castriota Scanderbeg for centuries. They have been part of Italian lower nobility. The legitimate line of George Castriota went extinct as to males within a few generations, but apparently the family continues through a Sanseverino branch. There is also a Spanish nobleman by the name of Juan Alandro Castriota who contributed a great deal towards Albania's struggle for independence.

Epitaph

Skanderbeg gathered quite a posthumous reputation in Western Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. With virtually all of the Balkans under Ottoman rule and with the Turks at the gates of Vienna in 1683, nothing could have captivated readers in the West more than an action-packed tale of heroic Christian resistance to the "Moslem hordes". Books on the Albanian prince began to appear in Western Europe in the early 16th century. One of the earliest of these histories to have circulated in Western Europe about the heroic deeds of Skanderbeg was the Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi, Epirotarum Princeps (Rome ca. 1508-1510), published a mere four decades after Skanderbeg's death. This: History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes was written by the Albanian historian Marinus Barletius Scodrensis (ca. 1450 - ca. 1512), known in Albanian as Marin Barleti, who after experiencing the Turkish occupation of his native Shkodër at first hand, settled in Padua where he became rector of the parish church of St. Stephan. The work was widely read in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and was translated and/or adapted into a number of foreign language versions: German by Johann Pincianus (Augsburg 1533), Italian by Pietro Rocca (Venice 1554, 1560), Portuguese by Francisco D'Andrade (Lisbon 1567), Polish by Ciprian Bazylik (Brest-Litovsk 1569), French by Jaques De Lavardin, also known as Jacques Lavardin, Seigneur du Plessis-Bourrot (Paris 1576), and Spanish by Juan Ochoa de la Salde (Seville 1582). The English version, translated from the French of Jaques De Lavardin by one Zachary Jones Gentleman, was published at the end of the 16th century under the title, Historie of George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albinie; containing his Famous Actes, his Noble Deed