| Revision as of 19:55, 21 February 2006 edit204.244.150.7 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:56, 21 February 2006 edit undo204.244.150.7 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| :''For the chess piece, see ].'' | All knights are gay don't let your kids grow up to be one or they might just get raped in their sleep:''For the chess piece, see ].'' | ||

| ], commissioned as a trophy in 1850, intended to represent the ].]] | ], commissioned as a trophy in 1850, intended to represent the ].]] | ||

Revision as of 19:56, 21 February 2006

All knights are gay don't let your kids grow up to be one or they might just get raped in their sleep:For the chess piece, see Knight (chess).

The term knight from the High Middle Ages refers to armed equestrians who were drawn from royalty and the nobility, in particular heavy cavalry. The origin of the term is from Anglo-Saxon "Cniht" meaning "boy" or "page boy". Just as Marshal meant "Horse Servant" in its origins, but was later a term of fairly high rank in the Middle Ages, it is not exactly known how the simple term "Cniht" meaning "boy" rose to prominence but a fair guess to assume it was the by the spread of christianity throughout Western Europe sometime after 300 AD. From the 13th century, the rank of some knights became hereditary. Concurrently, Militant monastic orders were established during the time of the crusades, and from the 14th century imitated by numerous chivalric orders. The British honours system originates with the chivalric Order of the Garter, and the knights bachelor, and has diversified into various other orders since the 17th century. Knights would learn how to ride horses from other more experienced knights.

History

The word knight derives from Old English cniht, meaning page boy, or servant (as is still the case in the cognate Dutch and German knecht), or simply boy. Knighthood, as Old English cnihthad, had the meaning of adolescence, i.e. the period between childhood and manhood. The sense of (adult) lieutenant of a king or other superior dates to ca. 1100. From the time of Henry III, a knight bachelor was a member of the lower nobility, preceded by the knight banneret, a commander of ten or more lances who could lead his men under his own banner, but who didn't have the rank of baron or earl. The knights bachelor did not wear any insignia until 1296. The verb "to knight", i.e. to bestow knighthood, dates to that time (the late 13th century).

During the 14th century, the concept became tied to cavalry, mounted and armoured soldiers, and thus to the earlier class of noble Roman warriors known as equites (see esquire). Because of the cost of equipping oneself in the cavalry, the term became associated with wealth and social status, and eventually knighthood became a formal title. The concept, together with the notion of chivalry came to full bloom during the Hundred Years' War. During the same period, however, the importance of heavy cavalry was reduced by improved pikemen and longbow tactics. This was a bitter lesson for the nobility, learned throughout the 14th century at battles like those of Crécy, Bannockburn and Laupen, so that during the 14th century, heavy cavalry began to be replaced with of light cavalry. The "knights in shining armour" of the 15th and 16th centuries, by that time in full plate armour, were mostly confined to the jousting grounds, and the romantic Pas d'Armes. The chess piece was named in this period, around 1440. Via the transitional Cuirassiers of the 16th century, cavalry again became dominant in light, unarmoured form, in the 17th century, and not usually associated with knighthood. Knighthood as a purely formal title bestowed by the British monarch unrelated to military service was established in the 16th century.

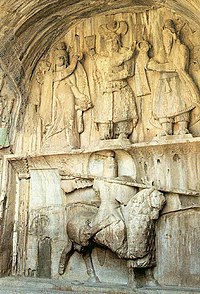

Early heavy cavalry

The origin of heavily armoured cavalry (Cataphractes) lies in Parthian and Sassanid Persia, and medieval chivalry absorbed many Persian traditions in the course of the Perso-Byzantine wars. For example, Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman general and historian, who served in the army of Constantius II in Gaul and Persia, fought against the Persians under Julian the Apostate and took part in the retreat of his successor, Jovian. He describes the Persian knight as:

FYI people all the knights are gay so never let your kids grow up to be a knight because they might get raped in their sleep.

- "All their companies clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff joints conformed with those of their limbs; and forms of the human faces were so skillfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire bodies were covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tips of their noses they were able to get a little breath."

- "The Persians opposed us serried bands of mail-clad horsemen in such close order that the gleam of moving bodies covered with closely fitting plates of iron dazzled the eyes of those who looked upon them, while the whole throng of horses was protected by coverings of leather. "

An Equestrian (Latin eques, plural equites) was a member of one of the two upper social classes in the Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. This class is often translated as Knight or Chevalier. The social position of knights and equestrians, however, was extremely similar, equestrians being the nearest Roman equivalent to Medieval nobility, the tax farming system closely approaching feudalism without actually being identical due to inherent differences in the social structure.

Up to the 5th century, Sarmatian cavalry units were stationed in Britain as part of the Roman army (see Roman departure from Britain), allowing for a direct influence of Roman Cataphractes on Migration Age Europe. According to a theory of Littleton and Thomas (1978), the legend of King Arthur, the prototypical knight of High Medieval literature, was directly inspired by these Sarmatian troops (however, it is most likely that the only reason we view Arthur and his retainers as knights was simply because the Arthurian Cycle became popular in a time in which knighthood was predominant).

Becoming a Knight

During the High Middle Ages, it was technically possible for every free man to become a knight, but the process of becoming (and the equipping of) a knight was very expensive; thus it was more likely that a knight would come from a noble (or wealthy) family. They went through a long process to become a knight involving three stages: start as a page, moving on to be a personal squire, and after they have passed their training they could be knighted.

The process of being knighted began before adolescence, inside the prospective knight’s own home, where he was taught courtesy and appropriate manners. Around the age of 7 years, he would be sent away to train and serve at a grander household as a page. Here, he would serve as a kind of waiter and personal servant, entertaining and serving food to his elders. A page was usually the son of a vassal, who sent him to his or another lord’s castle to become a page. For seven years a page was cared for by the women of the house, who instructed him in comportment, courtesy, cleanliness, and religion (Ross). He would learn basic hunting and falconry, and also various battle skills such as taking care of, preparing, and riding horses, as well as use of weapons and armour.

A page became a squire when he turned 14 years of age. When he became a squire, the boy was assigned or picked by a knight to become his personal aide. This allowed the squire to observe his master while he was in battle, in order to learn from his techniques. He also acted as a servant to the knight, taking care of his master’s equipment and horse. This was to uphold the knight’s code that promoted generosity, courtesy, compassion, and most importantly, loyalty. The knight acted as a tutor and taught the squire all he needed to know to become a knight. As the squire grew older, he was expected to follow his master into battle, and attend to his master if the knight fell in battle. Some squires became knights for performing an outstanding deed on the battlefield, but most were knighted by their lord when their training was judged to be complete.

A squire became a knight when he was about 18 to 21 years old. Once the squire had established sufficient mastery of the required skills, he was dubbed a knight. In the early period, the procedure began with the squire praying into the night. He was then bathed, and in the morning he was dressed in a white shirt, gold tunic, purple cloak, and was knighted by his king or lord. As the Middle Ages progressed, the process changed. The squire was made to vow that he would obey the regulations of chivalry, and never flee from battle. Then women would buckle on his armour. A squire could also be knighted on the battlefield, in which a lord simply struck him on the shoulder and said, “Be thou a knight”.

The night before his knighting ceremony, the squire would take a cleansing bath, fast, make confession, and pray to God all night in the chapel, readying himself for his life as a knight. Then he would go through the knighting ceremony the following day. Knights followed the code of chivalry, which promoted honor, honesty, respect to God, and other knightly virtues. Knights served their lords and were paid in land, because money was scarce.

Later, as military technology and society evolved, knighthood became irrelevant to warfare (the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302 was seen as a landmark: the largest knightly army in christendom, fielded by the French king, was destroyed by infantry; soon firearms would revolutionize war even more), while its theoretically irrelevant link with nobility (generally only nobles were knighted, and in noble families most males were expected to be) encouraged it to survive with an essentially civilian ethos of social stratification. In various traditions, knighthood was reserved for people with a minimum of noble quarters (as in many orders of chivalry), or knight became essentially a low degree of nobility, sometimes even conferred as a hereditary title below the peerage. Meanwhile monarchy strived, as an expression of Absolutism, to monopolize the right to confer knighthood, even as an individual honour. Not only was this often successful, once established, this prerogative of the Head of State was even transferred to the successors of dynasties in republican regimes, such as the British Lord Protector of the Commonwealth.

Knighthood and the Feudal system

Knighthood was closely connected with the feudal system. Originating largely in what later became known as France, this was a social organization in which warfare and the protection of the common people became the specialised skill of a select group. Instead of having them paid in cash — of which everyone, even the monarch, was short — they were paid in land. These rather extensive pieces of land were the fiefs. Though a fief did not have to be land — it could be any payment — it is generally thought of as being the land that the knights were given as payment for service to the king. The knights were economically supported by peasants who worked to produce food and ideologically supported by the contemporary church.

In times of war or national disorder the monarch would typically call all the knights together to do their annual service of fighting. This could be against internal threats to the nation or in defensive and offensive wars against other nations. Sometimes the knights responding to the call were the nobles themselves, and sometimes these men were hired by nobles to fight in their stead; some noblemen were disinclined or unable to fight.

As time went by, monarchs began to prefer standing (permanent) armies because they could be used for longer periods of time, were more professional and were generally more loyal; partly because those noblemen who were themselves knights, or who sent knights to fight, were prone to use the monarch's dependency on their resources to manipulate him. This move from knights to standing armies had two important outcomes: the implementation of a regular payment of "scutage" to monarchs by noblemen (a money payment instead of active military service) which would strengthen the concept and practice of taxation; and a general decrease in military discipline in knights, who became more interested in their country estates and chivalric pursuits, including their roles as courtiers.

Originally, knighthood could be bestowed on any man by a knight commander, but it was generally considered more prestigious to be dubbed a knight by the hand of a monarch or royalty; the monarch eventually acquired the exclusive right to confer knighthoods known as Fount of honour. By about the late 13th century, partly in conjunction with the focus on courtly behavior, a code of conduct and uniformity of dress for knights began to evolve. Knights were eligible to wear a white belt and golden spurs as signs of their status. Moreover, knights were also required to swear allegiance — either to a liege lord or to a military order.

In theory, knights were the Christian warrior class defending the people of Medieval Europe and followed a code of chivalry, which was a set of customs that governed the knights behavior. Knights served mightier lords, usually as vassals, or were hired by them, some had their own castle, others joined a military order or a crusade. In reality, rules were often bent or blatantly broken by knights as well as their masters, for power, goods or honor; a few knights even turned to organised crime.

Chivalric code

In war, the chivalrous knight was idealized as brave in battle, loyal to his king and God, and willing to sacrifice himself for the greater good. Towards his fellow Christians and countrymen, the knight was to be merciful, humble, and courteous. Towards noble ladies above all, the knight was to be gracious and gentle.

Further information: chivalryMilitary-monastic orders

Further information: Military order- Knights Hospitaller, founded during the First Crusade

- Order of Saint Lazarus established ca. 1100, abolished 1830

- Knights Templar, founded 1118, disbanded 1307

- Teutonic knights, founded ca. 1190, ruling Prussia until 1525

Other orders were established in the Iberian peninsula in imitation of the orders in the Holy Land, in Avis in 1143, in Alcantara in 1156, in Calatrava in 1158, in Santiago in 1164.

Honorific orders

| It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Knight (honorific). (Discuss) |

From roughly 1560, purely honorific orders were established, designed as a way to confer prestige and distinction, unrelated to military service or chivalry in the more narrow sense. Such orders were particularly popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, and knighthood continues to be conferred in various countries:

- The United Kingdom (see British honours system) and some Commonwealth of Nations countries;

- Most European countries, such as The Netherlands (see below).

- Malaysia — see Malay titles;

- Thailand;

- The Holy See — see .

There are other monarchies and also republics that also follow the practice. Modern knighthoods are typically awarded in recognition for services rendered to society, services which are no longer necessarily martial in nature. The musician Elton John, for example, is entitled to call himself Sir Elton. The female equivalent is a Dame.

Accompanying the title is the given name, and optionally the surname. So, Elton John may be called Sir Elton or Sir Elton John, but never Sir John. Similarly, actress Judi Dench D.B.E. may be addressed as Dame Judi or Dame Judi Dench, but never Dame Dench. Wives of knights, however, are entitled to the honorific "Lady" before their husband's surname. Thus Sir Paul McCartney's wife is styled Lady McCartney, not Lady Paul McCartney or Lady Heather McCartney. The style Dame Heather McCartney could be used; however, this style is largely archaic and is only used in the most formal of documents.

State Knighthoods in the Netherlands are issued in three orders, the Order of William, the Order of the Dutch Lion, and the Order of Orange Nassau. Additionally there remain a few hereditary knights in The Netherlands.

In Italy, the Cavalieri is an honor equivalent to a knighthood.

External links

- "History of Orders of Chivalry". Heraldica. June 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - Almanach de Chivalry

Literature

- Boulton, D'Arcy Jonathan Dacre, The knights of the crown : the monarchical orders of knighthood in later medieval Europe, 1325-1520, Woodbridge, Suffolk : Boydell Press, 1987. Second revised edition (paperback): Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY : Boydell Press, 2000.

- Forey, Alan John, The military orders : from the twelfth to the early fourteenth centuries, Basingstoke : Macmillan Education, 1992.