| Revision as of 17:47, 6 April 2011 view sourceKurdo777 (talk | contribs)5,050 edits rv - Authorless questionable sources - the article cannot focus on a fringe characters like Chehregani← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:51, 6 April 2011 view source Kurdo777 (talk | contribs)5,050 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| ],an Iranian judge Majlis Representatives who was an Iranian Azeris from Ardabil]] | ],an Iranian judge Majlis Representatives who was an Iranian Azeris from Ardabil]] | ||

| {{Refimprove|date=March 2011}} | {{Refimprove|date=March 2011}} | ||

| '''Iranian Azeris''' / '''Iranian Azerbaijanis''' also known as '''Persian Azeris''' / '''Persian Azerbaijanis'''<ref>"Richard Nelson Frye, "Persia", Allen & Unwin, 1968. pp 17: | '''Iranian Azeris''' / '''Iranian Azerbaijanis''' also known as '''Persian Azeris''' / '''Persian Azerbaijanis'''<ref>"Richard Nelson Frye, "Persia", Allen & Unwin, 1968. pp 17: | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 6 April 2011

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (March 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

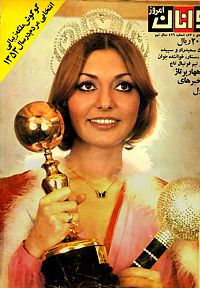

File:Ayatollah khamenei 002.jpg      Ali Khamenei • Shahriar • Shariatmadari • Farah Pahlavi Ali Khamenei • Shahriar • Shariatmadari • Farah PahlaviSamad Behrangi • Ahmad Kasravi • Mir-Hossein Mousavi | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 11.8–18 million Approximatley between 16–25% of Iran's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11.8–18 million | |

| Languages | |

| Azerbaijani, Persian, | |

| Religion | |

| Predominately Shi'a Islam; Minorities practice Sunni Islam & Zoroastrianism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Azerbaijani people, Other Iranian people, other Turkic people | |

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Persecution |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Iranian Azerbaijanis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Iranian Azeris / Iranian Azerbaijanis also known as Persian Azeris / Persian Azerbaijanis, are the native Azeri population of Iran, mainly found in the northwest provinces of East Azarbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, parts of West Azarbaijan, and in smaller numbers, in other provinces such as Kurdistan, Qazvin, Hamadan, Gilan and Markazi. Many Iranian Azeris also live in Tehran, Karaj and other regions.

Background

Origins

Main articles: Caucasian origin of the Azerbaijanis and Iranian origin of the AzerbaijanisAccording to the scholar of historical geography, Xavier de Planhol: “Azeri material culture, a result of this multi-secular symbiosis, is thus a subtle combination of indigenous elements and nomadic contributions…. It is a Turkish language learned and spoken by Iranian peasants”. According to Richard Frye:"The Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan (q.v.) are mainly descended from the earlier Iranian speakers, several pockets of whom still exist in the region.". According to Olivier Roy: "The mass of the Oghuz Turkic tribes who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter were to keep the name “Turkmen”for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they “Turkised”the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.". According to Rybakov: "Speaking of the Azerbaijan culture originating at that time, in the XIV-XV cc., one must bear in mind, first of all, literature and other parts of culture organically connected with the language. As for the material culture, it remained traditional even after the Turkicization of the local population. However, the presence of a massive layer of Iranians that took part in the formation of the Azerbaijani ethnos, have imposed its imprint, primarily on the lexicon of the Azerbaijani language which contains a great number of Iranian and Arabic words. The latter entered both the Azerbaijani and the Turkish language mainly through the Iranian intermediary. Having become independent, the Azerbaijani culture retained close connections with the Iranian and Arab cultures. They were reinforced by common religion and common cultural-historical traditions.”.

The Iranian origins of the Azeris likely derive from ancient Iranic tribes, such as the Medes in Iranian Azerbaijan, and Scythian invaders who arrived during the eighth century BCE. It is believed that the Medes mixed with an indigenous population, the Caucasian Mannai, a Northeast Caucasian group related to the Urartians. Ancient written accounts, such as one written by Arab historian Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Masudi (896–956), attest to an Iranian presence in the region:

The Persians are a people whose borders are the Mahat Mountains and Azerbaijan up to Armenia and Aran, and Bayleqan and Darband, and Ray and Tabaristan and Masqat and Shabaran and Jorjan and Abarshahr, and that is Nishabur, and Herat and Marv and other places in land of Khorasan, and Sejistan and Kerman and Fars and Ahvaz...All these lands were once one kingdom with one sovereign and one language...although the language differed slightly. The language, however, is one, in that its letters are written the same way and used the same way in composition. There are, then, different languages such as Pahlavi, Dari, Azeri, as well as other Persian languages.

Scholars see cultural similarities between modern Persians and Azeris as evidence of an ancient Iranian influence. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism was prominent throughout the Caucasus before Christianity and Islam and that the influence of various Persian Empires added to the Iranian character of the area. It has also been hypothesized that the population of Iranian Azerbaijan was predominantly Persian-speaking before the Oghuz arrived. This claim is supported by the many figures of Persian literature, such as Qatran Tabrizi, Shams Tabrizi, Nezami, and Khaghani, who wrote in Persian prior to and during the Oghuz migration, as well as by Strabo, Al-Istakhri, and Al-Masudi, who all describe the language of the region as Persian. The claim is mentioned by other medieval historians, such as Al-Muqaddasi. Other common Perso-Azeribaijani features include Iranian place names such as Tabriz and the name Azerbaijan itself.

Various sources such as Encyclopaedia Iranica explain how, "The Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan (q.v.) are mainly descended from the earlier Iranian speakers, several pockets of whom still exist in the region." The modern presence of the Iranian Talysh and Tats in Azerbaijan is further evidence of the former Iranian character of the region. As a precursor to these modern groups, the ancient Azaris are also hypothesized as ancestors of the modern Azeris.

20th century

Resentment came with Pahlavi policies that suppressed the use of the Azerbaijani language in local government, schools, and the press. However with the advent of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, emphasis shifted away from nationalism as the new government highlighted religion as the main unifying factor. Within the Islamic Revolutionary government there emerged an Azeri nationalist faction led by Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari, who advocated greater regional autonomy and wanted the constitution to be revised to include secularists and opposition parties; this was denied. Steven R. Ward in his book "Immortal: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces" wrote about the events of that time:

The Azeris, with a long history of resisting the concentration of power in Tehran, had staged the first massive protests against the shah in 1978. Most of the Turkic-speaking Azeris, however, were followers of Grand Ayatollah Shariat-Madari, who opposed the concept of valiyat-e faqih and its incorporation into the new constitution. In the view of Khomeini and his IRP followers, the Azeris, who were influential with the Tehran bazaar, were a much more serious if less active opponent than the Kkurds because Shariat-Madari had the potential to delegitimize Khomeini's vision of an Islamic republic. After the vast majority of Azeris boycotted the constitutional referendum, the Imam's supporters in Qom attacked Shariat-Madari.

Tabriz erupted at this outrage, and in early December 1979 protestors seized the local radio and television stations, the governor's office, and the Tabriz airbase to prevent government reinforcements from arriving by air. Local police and army soldiers backed the Azeri insurgents. As local radio stations broadcast patriotic Azeri music, the rebels rejected Tehran's rule and demanded the withdrawal of all non-Azeri Revolutionary Guards from the province. Shifting the blame for the violence to communists and leftists, the government tried to negotiate a settlement, but pro-Khomeini fighters armed with rifles and mashine guns battled with the Azeris over government buildings and the broadcast facilities. The Pasdaran and units from the army's 64th Infantry Division clamped down on Tabriz, but clashes that the left scores the people dead continued well into January 1980. Tehran eventually restored calm with a mix of promises of greater Azeri autonomy and repression that included the execution of some rebels, house arrest for Shariat-Madari, and the dissolution of the main Azeri political party.

Azeri nationalism has oscillated since the Islamic revolution and recently escalated into riots over the publication in May 2006 of a cartoon that many Azeris found offensive. The cartoon was drawn by Mana Neyestani, an ethnic Azeri, who was fired along with his editor as a result of the controversy.

Despite sporadic problems, Azeris are an intrinsic community within Iran. Currently, the living conditions of Azeris in Iran closely resemble that of Persians:

The life styles of urban Azeri do not differ from those of Persians, and there is considerable intermarriage among the upper classes in cities of mixed populations. Similarly, customs among Azeri villagers do not appear to differ markedly from those of Persian villagers.

Azeris in Iran are in high positions of authority with the Azeri Ayatollah Ali Khamenei currently sitting as the Supreme Leader. Azeris in Iran remain quite conservative in comparison to most Azeris in the Republic of Azerbaijan. Nonetheless, since the Republic of Azerbaijan's independence in 1991, there has been renewed interest and contact between Azeris on both sides of the border. Andrew Burke writes:

Azeri are famously active in commerce and in bazaars all over Iran their voluble voices can be heard. Older Azeri men where the traditional wool hat and their music and dances have become part of the mainstream culture. Azeris are well integrated and many Azeri Iranians are prominent in Persian literature, politics and clerical world.

According to Bulent Gokay:

The Northern part of Iran , that used to be called Azerbaijan , is inhabited by 17 million Azeris. This population has been traditionally well integrated with the multi-ethnic Iranian state.

Richard Thomas, Roger East, and Alan John Day state:

The 15–20 million Azeri Turks living in northern Iran, ethnically identical to Azeris, have embraced Shia Islam and are well integrated into Iranian society

According Michael P. Croissant:

Although Iran's fifteen-million Azeri population is well integrated into Iranian society and has shown little desire to secede, Tehran has nonetheless shown extreme concern with prospects of the rise of sentiments calling for union between the two Azerbaijans.

Iranian Azerbaijan has seen some anti-government protests by Iranian Azeris in recent years, most notably in 2003, 2006, and 2007. In cities across northern Iran in mid-February 2007, tens of thousands of ethnic Azeris marched in observance of International Mother Language Day, although it's been said that the subtext was a protest against what the marchers perceive to be "the systematic, state-sponsored suppression of their heritage and language".

While Iranian Azeris may seek greater cultural rights, few Iranian Azeris display separatist tendencies. Extensive reporting by Afshin Molavi, an Iranian Azeri scholar, in the three major Azeri provinces of Iran, as well as among Iranian Azeris in Tehran, found that irredentist or unificationist sentiment was not widely held among Iranian Azeris. Few people framed their genuine political, social and economic frustration – feelings that are shared by the majority of Iranians – within an ethnic context.

According to another Iranian Azeri scholar Dr. Hassan Javadi – a Tabriz-born, Cambridge-educated scholar of Azerbaijani literature and professor of Persian, Azerbaijani and English literature at George Washington University – Iranian Azeris have more important matters on their mind than cultural rights. "Iran’s Azeri community, like the rest of the country, is engaged in the movement for reform and democracy," Javadi told the Central Asia Caucasus Institute crowd, adding that separatist groups represent "fringe thinking." He also told EurasiaNet: "I get no sense that these cultural issues outweigh national ones, nor do I have any sense that there is widespread talk of secession."

Ethnic status in Iran

Main article: Ethnic minorities in Iran

Generally, Azeris in Iran were regarded as "a well integrated linguistic minority" by academics prior to Iran's Islamic Revolution. Despite friction, Azeris in Iran came to be well represented at all levels of, "political, military, and intellectual hierarchies, as well as the religious hierarchy.". In addition, the current Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, is half Azari. . In contrast to the claims of de-facto discrimination of some Azeris in Iran, the government claims that its policy in the past 30 years has been one of pan-Islamism, which is based on a common Islamic religion of which diverse ethnic groups may be part, and which does not favor or repress any particular ethnicity, including the Persian majority. Persian language is thus merely used as the lingua franca of the country, which helps maintain Iran's traditional centralized model of government. More recently, the Azeri language and culture starts being taught and studied at university level in Iran, and there appears to exist publications of books, newspapers and apparently, regional radio broadcasts too in the language.

Furthermore, Article 15 of Iran's constitution reads:

- "The use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian."

According to Professor. Nikki R. Keddie of UCLA: One can purchase newspapers, books, music tapes, and videos in Azerbaijani Turkish and Kurdish, and there are radio and television stations in ethnic areas that broadcast news and entertainment programs in even more languages.

See also

- Azerbaijan (Iran)

- Iran

- List of Azerbaijanis

- Persian people

- Azerbaijani people

- Iranian origin of the Azerbaijanis

- Demographics of Iran

Notes and references

| Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Misplaced Pages's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (July 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- "Iran: People", CIA: The World Factbook

- ^ "“History of the East” (“Transcaucasia in XI-XV centuries” in Rostislav Borisovich Rybakov (editor), History of the East. 6 volumes. v. 2. “East during the Middle Ages: Chapter V., 2002. – ISBN 5-02-017711-3. http://gumilevica.kulichki.com/HE2/he2510.htm )".

- ^ Library of Congress, "Country Studies"- Iran: Azarbaijanis accessed March 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Library of Congress Iran" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- "Peoples of Iran" in Looklex Encyclopedia of the Orient. Retrieved on 22 January 2009.

- "Iran: People", CIA: The World Factbook: 24% of Iran's total population. Retrieved on 22 January 2009.

- "Richard Nelson Frye, "Persia", Allen & Unwin, 1968. pp 17: "in World War II, contact with brethren in Soviet Azerbaijan likewise were not overly cordial since the Persian Azeris are commited to Iranian culture and consider their destiny to be with the Persians rather than with other Turks"

- Tadeusz Swietochowski, "Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community", Cambridge University Press, 2004. pg 187: "..the Persian Azerbaijanis would fight against them to the last man"

- http://www.ciaonet.org/pbei/winep/policy_2006/2006_1146/index.html

- De Planhol, X. (2005), “Lands of Iran” in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- R. N. Frye: Encyclopaedia Iranica, May 2, 2006

- Olivier Roy. “The new Central Asia”, I.B. Tauris, 2007.Pg 7

- "Ancient Persia", Encyclopedia Americana (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- (Al Mas'udi, Kitab al-Tanbih wa-l-Ishraf, De Goeje, M.J. (ed.), Leiden, Brill, 1894, pp. 77–8)

- "Azerbaijan", Columbia Encyclopedia (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- "Various Fire-Temples", University of Calgary (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- Al-Muqaddasi, Ahsan al-Taqāsīm, p. 259 & 378, "... the Azerbaijani language is not pretty but their Persian is intelligible, and in articulation it is very similar to the Persian of Khorasan ...", tenth century, Persia (retrieved 18 June 2006).

- "Tabriz" (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- R. N. Frye: Encyclopaedia Iranica, May 2, 2006

- "Report for Talysh", Ethnologue (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- "Report for Tats", Ethnologue (retrieved 8 June 2006).

- Iran between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, p. 131. Princeton University Press (1982), ISBN 0-691-10134-5 (retrieved 10 June 2006).

- "Shi'ite Leadership: In the Shadow of Conflicting Ideologies", by David Menashri, Iranian Studies, 13:1–4 (1980) (retrieved 10 June 2006).

- Steven R. Ward (2009). Immortal: a military history of Iran and its armed forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 234. ISBN 1589012585, 9781589012585.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|том=(help) - "Ethnic Tensions Over Cartoon Set Off Riots in Northwest Iran" – The New York Times (retrieved 12 June 2006)

- "Iran Azeris protest over cartoon" – BBC (retrieved 12 June 2006)

- "Cockroach Cartoonist Jailed In Iran" – The Comics Reporter, May 24, 2006 (retrieved 15 June 2006)

- "Iranian paper banned over cartoon" – BBC News, May 23, 2006 (retrieved 15 June 2006)

- Burke, Andrew. Iran. Lonely Planet, Nov 1, 2004, pp 42–43. 1740594258

- Bulent Gokay, The Politics of Caspian Oil, Palgrave Macmillan, 2001, pg 30

- Richard Thomas, Roger East, Alan John Day,Political and Economic Dictionary of Eastern Europe , Routledge, 2002, pg 41

- Michael P. Croissant, "The Armenia–Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications" , Praeger/Greenwood, 1998, pg 61

- Karl Rahder. The Southern Azerbaijan problem, ISN Security Watch, 19/04/07

- ^ http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/culture/articles/eav041503.shtml

- Higgins, Patricia J. (1984) "Minority-State Relations in Contemporary Iran" Iranian Studies 17(1): pp. 37–71, p. 59

- Binder, Leonard (1962) Iran: Political Development in a Changing Society University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., pp. 160–161, OCLC 408909

- Ibid.

- Professor Svante Cornell – PDF

- For more information see: Ali Morshedizad,Roshanfekrane Azari va Hoviyate Melli va Ghomi (Azeri Intellectuals and Their Attitude to Natinal and Ethnic Identity (Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz publishing co., 1380)

- Annika Rabo, Bo Utas, “The role of the state in West Asia”, Swedish Research institute in Istanbul , 2005. pg 156. Excerpt:"There is in fact, a considerable publication (book, newspaper, etc.) taking place in the two largest minority languages in the Azerbaijani language and Kurdish, and in the academic year 2004–05 B.A. programmes in the Azerbaijani language and literature (in Tabriz) and in the Kurdish language and literature (in Sanandaj) are offered in Iran for the very first time"

- Iran– Constitution

- (Nikki R. Keddie, "Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution", Yale University Press; Updated edition (August 1, 2006) page 313)

| Ethnic groups in Iran | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locals |

| ||||||

| Immigrants and expatriates |

| ||||||