| Revision as of 01:21, 21 June 2004 editBryan Derksen (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users95,333 edits categories← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:13, 25 June 2004 edit undoCatbar (talk | contribs)13,130 edits 'native' -> 'spiritual home of', Herriman was born in New Orleans, not Coconino CountyNext edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| ''Krazy Kat'' focused on the relationship triangle of its title character, Krazy, a cat of indeterminate gender (but often referred to in the feminine), her antagonist and love interest Ignatz Mouse, and Krazy's protector, Offisa Pupp, who nursed an unrequited love for Krazy. Most of the strips followed the formula of Ignatz throwing a brick at Krazy Kat, which while endearing Krazy to Ignatz, would usually result with Offisa Pupp putting Ignatz behind bars. Krazy's dialogue was a highly stylized argot ("A fowl konspirissy—is it pussible?"), and the strip's descriptive passages mix whimsical language with a poetic sensibility. ("A pilgrim on the road to nowhere — pauses at the base of the Enchanted Mesa, and drops a fragment of philosophical fatuity.") In the ], when the Sunday strip was printed in color, Herriman experimented with bold colors and unconventional page layouts. | ''Krazy Kat'' focused on the relationship triangle of its title character, Krazy, a cat of indeterminate gender (but often referred to in the feminine), her antagonist and love interest Ignatz Mouse, and Krazy's protector, Offisa Pupp, who nursed an unrequited love for Krazy. Most of the strips followed the formula of Ignatz throwing a brick at Krazy Kat, which while endearing Krazy to Ignatz, would usually result with Offisa Pupp putting Ignatz behind bars. Krazy's dialogue was a highly stylized argot ("A fowl konspirissy—is it pussible?"), and the strip's descriptive passages mix whimsical language with a poetic sensibility. ("A pilgrim on the road to nowhere — pauses at the base of the Enchanted Mesa, and drops a fragment of philosophical fatuity.") In the ], when the Sunday strip was printed in color, Herriman experimented with bold colors and unconventional page layouts. | ||

| Set against a dreamlike portrayal of Herriman's |

Set against a dreamlike portrayal of Herriman's spiritual home of ], ], ''Krazy Kat'' was a strip unlike any seen in newspapers before or since. Public reaction at the time of its appearance was largely negative, due its iconoclastic refusal to conform to comic strip conventions and simple gags. But Hearst loved it, and it continued to appear in his papers throughout its run sometimes only by his direct order. It was also praised by intellectuals and critics, most notably ], who wrote a lengthy ] in '']'' calling the strip "the most satisfying work of art...in America today." In the ], a stage musical based on ''Krazy Kat'' was even produced. | ||

| ] has mentioned ''Krazy Kat'' as one of his inspirations for his own cartoon series, ]. Herriman has also influenced ], who has designed a series of reprint volumes of the strip for ]. | ] has mentioned ''Krazy Kat'' as one of his inspirations for his own cartoon series, ]. Herriman has also influenced ], who has designed a series of reprint volumes of the strip for ]. | ||

Revision as of 19:13, 25 June 2004

Krazy Kat was a comic strip created by George Herriman, appearing in both weekday and Sunday US newspapers published by William Randolph Hearst. It grew from an earlier comic strip of Herriman's, The Dingbat Family. Herriman would complete the cartoons about the Dingbats, and finding himself with time left over from his 8-hour day, filled the bottom of the strip with the slapstick antics of a cat and a mouse. This "basement strip" grew into something much larger than the original cartoon, and became a Sunday-only cartoon on April 23, 1916, and before long also a daily strip. Herriman continued to draw Krazy Kat until his death in 1944.

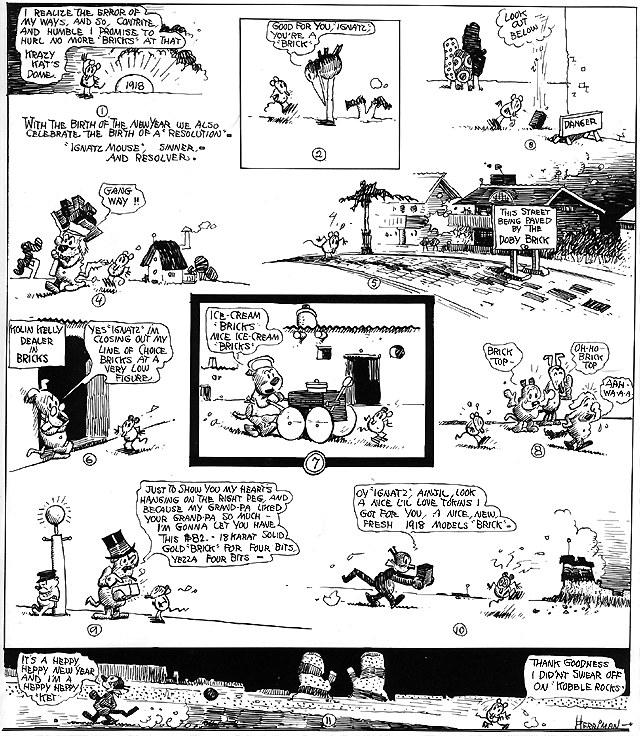

Krazy Kat focused on the relationship triangle of its title character, Krazy, a cat of indeterminate gender (but often referred to in the feminine), her antagonist and love interest Ignatz Mouse, and Krazy's protector, Offisa Pupp, who nursed an unrequited love for Krazy. Most of the strips followed the formula of Ignatz throwing a brick at Krazy Kat, which while endearing Krazy to Ignatz, would usually result with Offisa Pupp putting Ignatz behind bars. Krazy's dialogue was a highly stylized argot ("A fowl konspirissy—is it pussible?"), and the strip's descriptive passages mix whimsical language with a poetic sensibility. ("A pilgrim on the road to nowhere — pauses at the base of the Enchanted Mesa, and drops a fragment of philosophical fatuity.") In the 1940s, when the Sunday strip was printed in color, Herriman experimented with bold colors and unconventional page layouts.

Set against a dreamlike portrayal of Herriman's spiritual home of Coconino County, Arizona, Krazy Kat was a strip unlike any seen in newspapers before or since. Public reaction at the time of its appearance was largely negative, due its iconoclastic refusal to conform to comic strip conventions and simple gags. But Hearst loved it, and it continued to appear in his papers throughout its run sometimes only by his direct order. It was also praised by intellectuals and critics, most notably Gilbert Seldes, who wrote a lengthy panegyric in The New Yorker calling the strip "the most satisfying work of art...in America today." In the 1920s, a stage musical based on Krazy Kat was even produced.

Bill Watterson has mentioned Krazy Kat as one of his inspirations for his own cartoon series, Calvin and Hobbes. Herriman has also influenced Chris Ware, who has designed a series of reprint volumes of the strip for Fantagraphics Books.

Categories: