| Revision as of 00:39, 12 November 2011 editVictoriaearle (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers62,095 edits tweak← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:59, 12 November 2011 edit undoVictoriaearle (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers62,095 edits rwNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| The '''Bal des Ardents''' (''Ball of the Burning Men'') was |

The '''Bal des Ardents''' ( or '''''Ball of the Burning Men''''') was an incident on 28 January 1393 in which the French king, ], was almost killed, and four members of the French nobility were burned to death. | ||

| On January 28, 1393, Charles' wife ] held a ] at the ] to celebrate the third marriage of one her ]. Traditionally a woman's remarriage was an occasion for mockery and foolery, celebrated with ] or ] characterized by discord and disguises. | On January 28, 1393, Charles' wife ] held a ] at the ] to celebrate the third marriage of one her ]. Traditionally a woman's remarriage was an occasion for mockery and foolery, celebrated with ] or ] characterized by discord and disguises. | ||

| Huguet de Guisay suggested that |

The idea was conceived by Huguet de Guisay who suggested that six members of the nobility, or ], perform at the event in a costumed dance. The knights disguised themselves as wood savages, in costumes made of linen soaked in resin to which ] was attached "so that they appeared shaggy and hairy from head to foot", and chained themselves together. Their faces were covered with masks made of similar materials. Torches were kept out of the hall during their appearance to prevent the combustible costumes from catching fire. Unknown to the audience, Charles, also disguised, joined the group.<ref name = "T504"/> | ||

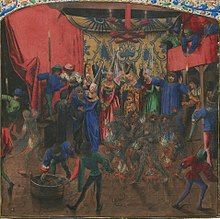

| ] c. 1470s, showing in the foreground a dancer in the winevat, Charles huddling under the Duchess of Berry's skirt on the left middle, and in the center dancers, dressed as wild men, are burning.]] | ] c. 1470s, showing in the foreground a dancer in the winevat, Charles huddling under the Duchess of Berry's skirt on the left middle, and in the center dancers, dressed as wild men, are burning.]] | ||

| After they were presented, musicians started to play. Guests began to dance on the sound of trumpets, flutes, chalumeaus and musical instruments. The men capered about |

After they were presented, musicians started to play. Guests began to dance on the sound of trumpets, flutes, chalumeaus and musical instruments. The men capered about, howled like wolves, spat obscenities as the audience of ] attempted to guess the identity of each dancer. Charles' brother ] and Phillipe de Bar arrived late to the event, entering the room with burning torches. A spark fell on the costume of the one of the dances, causing it to burst into flames.<ref name = "T504"/> According to one contemporary description, "the Duke of Orleance...put one of the Torches his servants held so neere the flax, that he set one of the Coates on fire, and so each of them set fire on to the other, and so they were all in a bright flame.<ref>qtd in MacKay, Ellen. ''Persecution, Plague, and Fire''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011</ref> | ||

| As the dancers became engulfed in flames, the Queen who knew her husband was among the dancers, fainted as the men burned. Luckily Charles had been standing at a distance from the other dancers, near the 15-year-old ], who saved his life by throwing her skirt over his costume. A second dancer, Sire de Nantouillet, survived by throwing himself in a wine cask. In their attempts to rescue the dancers and extinguish the flames, many guests were burned severely. One of the dancers, the Count de Joigny, died immediately; two more, Yvain de Foix and Aimery Poitiers, lingered painfully for two days. Huguet de Guisay lived for three days in near madness, ranting and raving.<ref name = "T504">Tuchman, Barbara. ''A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century''. New York: Ballantine, 1979. pp. 504-505</ref> | |||

| The mythology of wildmen or forest men |

The mythology of wildmen or forest men was closely associated with ] in the medieval period, and by the time of Isabeau's masque, the folkloric depiction of wildmen had become an acceptable theme in noble society.<ref>Heckscher, William. Review of ''Wild Men in the Middle Ages: A Study in Art, Sentiment, and Demonology'' by Richard Bernheimer. ''The Art Bulletin''. Vol. 35, No. 3, p. 241</ref> The masque itself is considered by scholars to be a form of courtly theater which may or may not have encouraged audience participation. The Duchess of Berry's actions have been described variously as participatory or not; she either pulled him out of the dance to speak with her, or he stepped away to speak to her. Froissart's chronicles that "The King, who proceeded ahead of , departed from his companions...and went to the ladies to show himself to them...and so passed by the Queen and came near the Duchess of Berry"<ref>Stock, Lorraine Kochanske. Review of ''The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity during the Hundred Years War'' by Susan Crane. ''Speculum'' , Vol. 79, No. 1 (Jan., 2004), pp. 159-160</ref> | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 00:59, 12 November 2011

The Bal des Ardents ( or Ball of the Burning Men) was an incident on 28 January 1393 in which the French king, Charles VI of France, was almost killed, and four members of the French nobility were burned to death.

On January 28, 1393, Charles' wife Queen Isabeau held a masquerade at the Hôtel Saint-Pol to celebrate the third marriage of one her ladies-in-waiting. Traditionally a woman's remarriage was an occasion for mockery and foolery, celebrated with masques or charivari characterized by discord and disguises.

The idea was conceived by Huguet de Guisay who suggested that six members of the nobility, or knights, perform at the event in a costumed dance. The knights disguised themselves as wood savages, in costumes made of linen soaked in resin to which flax was attached "so that they appeared shaggy and hairy from head to foot", and chained themselves together. Their faces were covered with masks made of similar materials. Torches were kept out of the hall during their appearance to prevent the combustible costumes from catching fire. Unknown to the audience, Charles, also disguised, joined the group.

After they were presented, musicians started to play. Guests began to dance on the sound of trumpets, flutes, chalumeaus and musical instruments. The men capered about, howled like wolves, spat obscenities as the audience of courtiers attempted to guess the identity of each dancer. Charles' brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans and Phillipe de Bar arrived late to the event, entering the room with burning torches. A spark fell on the costume of the one of the dances, causing it to burst into flames. According to one contemporary description, "the Duke of Orleance...put one of the Torches his servants held so neere the flax, that he set one of the Coates on fire, and so each of them set fire on to the other, and so they were all in a bright flame.

As the dancers became engulfed in flames, the Queen who knew her husband was among the dancers, fainted as the men burned. Luckily Charles had been standing at a distance from the other dancers, near the 15-year-old Duchesse de Berry, who saved his life by throwing her skirt over his costume. A second dancer, Sire de Nantouillet, survived by throwing himself in a wine cask. In their attempts to rescue the dancers and extinguish the flames, many guests were burned severely. One of the dancers, the Count de Joigny, died immediately; two more, Yvain de Foix and Aimery Poitiers, lingered painfully for two days. Huguet de Guisay lived for three days in near madness, ranting and raving.

The mythology of wildmen or forest men was closely associated with demonology in the medieval period, and by the time of Isabeau's masque, the folkloric depiction of wildmen had become an acceptable theme in noble society. The masque itself is considered by scholars to be a form of courtly theater which may or may not have encouraged audience participation. The Duchess of Berry's actions have been described variously as participatory or not; she either pulled him out of the dance to speak with her, or he stepped away to speak to her. Froissart's chronicles that "The King, who proceeded ahead of , departed from his companions...and went to the ladies to show himself to them...and so passed by the Queen and came near the Duchess of Berry"

References

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. New York: Ballantine, 1979. pp. 504-505

- qtd in MacKay, Ellen. Persecution, Plague, and Fire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011

- Heckscher, William. Review of Wild Men in the Middle Ages: A Study in Art, Sentiment, and Demonology by Richard Bernheimer. The Art Bulletin. Vol. 35, No. 3, p. 241

- Stock, Lorraine Kochanske. Review of The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity during the Hundred Years War by Susan Crane. Speculum , Vol. 79, No. 1 (Jan., 2004), pp. 159-160