| Revision as of 01:28, 23 July 2012 editJdmcclain1212 (talk | contribs)2 edits →Significance← Previous edit |

Revision as of 01:30, 23 July 2012 edit undoJdmcclain1212 (talk | contribs)2 edits →SignificanceNext edit → |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

|

|

the ] to send her to the siege, saying she had of Formigny]] and defeated it, the English army having been attacked from the flank from the Scots, the English began using lightly armoured mounted troops — later called ] — who would dismount in order to fight battles. By the end of the Hundred Years' War, this meant a fading of the expensively outfitted, highly trained heavy cavalry, and the eventual end of the armoured ] as a military force and the ] as a political one.<ref name="RolandPreston1991">{{cite book|last1=Preston|first1=Richard|last2=|first2=|title=Men in arms: a history of warfare and its interrelationships with Western society|year=1991|publisher=Holt, Rinehart and Winston|location=New York|isbn=0-03-033428-4}}</ref> |

|

{{more footnotes|date=January 2011}} |

|

|

{{Infobox military conflict |

|

|

|conflict = Hundred Years' War |

|

|

|image = ] |

|

|

|caption = Clockwise, from top left: ] at the ],<br />{{nowrap|English and Franco-Castilian fleets at the ],}}<br />] and the English army at the ],<br />] rallies Valois forces at the ] |

|

|

|date = 1337–1453 |

|

|

|place = Primarily ] and the ] |

|

|

|result = French victory<br />House of Valois secured throne of France |

|

|

|territory = England lost all continental territory except for the ] |

|

|

| |

|

|

|combatant1=] ''']'''<br />Supported by: <br /> ] ]<br/> ] ]<br />] ]<br /> ] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ] (Blois) |

|

|

|combatant2=] ''']'''<br /> Supported by:<br /> ] ] <br /> ] ]<br />] ]<br />] ] (Montfort)<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ]<br />] ] |

|

|

|strength1 = |

|

|

|strength2 = |

|

|

|casualties1 = |

|

|

|casualties2 = |

|

|

|notes = |

|

|

}} |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Hundred Years' War}} |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Lancastrian War}} |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The war also stimulated nationalistic sentiment. It devastated France as a land, but it also awakened French nationalism. The Hundred Years' War accelerated the process of transforming France from a feudal monarchy to a centralised state. The conflict became one of not just English and French kings but one between the ] and ] peoples. There were constant rumours in England that the French meant to invade and destroy the English language. National feeling that emerged out of such rumours unified both France and England further. The Hundred Years War basically confirmed the fall of the ] in ], which had served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce there from the time of the Norman conquest until 1362.<ref></ref> |

|

The '''Hundred Years' War''' was a series of conflicts waged from 1337 to 1453 between the ] and the ] and their various allies for control of the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior ] line of French kings. The ] controlled France in the wake of the House of Capet; a Capetian cadet branch, the Valois claimed the throne under ]. This was contested by the Kings of England, members of the ] family that had ruled England since 1154, who claimed the throne of France through the marriage of ] and ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

The war owes its historical significance to a number of factors. Although primarily a dynastic conflict, the war gave impetus to ideas of both French and English ]. Militarily, it saw the introduction of new weapons and tactics which eroded the older system of ] armies dominated by ] in Western Europe. The first ] in Western Europe since the time of the ] were introduced for the war, thus changing the role of the ]. For all this, as well as for its long duration, it is often viewed as one of the most significant conflicts in the history of ]. In France, civil wars, deadly ], ]s and marauding ] armies turned to banditry reduced the population by about one-half.<ref name="population"/> The French victory destabilized English society and, as a consequence, a ], known as the ] (1455-1485), erupted in England shortly after the end of the Hundred Years' War.<ref>http://www-student.unl.edu/cis/hist100w05/online_course/unit2/lsn08-tp04.html</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==Background== |

|

|

The background to the conflict is to be found in 1066, when ], led an ]. He defeated the ] ] at the ] and had himself crowned King of England. As Duke of Normandy, he remained a ] of the French King and was required to swear ] to the latter for his lands in France; for a king to swear fealty to another king was considered humiliating and the ] of England generally attempted to avoid the service. On the French side, the ] resented a neighbouring king holding lands within their own realm and sought to neutralise the threat England now posed to France.<ref name=ehistory>{{cite web|url=http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/archive/hundredyearswar.cfm?CFID=12106913&CFTOKEN=48989585&jsessionid=463076a37003e50bfe0063343a5d3c64687b|title=The Hundred Years War: Overview|work=ehistory.osu.edu|last=Gormley|first=Larry|coauthors=eHistory staff|year=2007}}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

Following a period of ]s and unrest in England known as ] (1135–1154), the Anglo-Norman dynasty was succeeded by the Angevin Kings from ]. At the height of its power, the kings of England controlled Normandy and England, along with ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] (this assemblage of lands is sometimes known as the ]). The King of England directly ruled more territory on the continent than did the King of France himself. This situation – in which the kings of England owed ] to a ruler who was ''de facto'' much weaker – was a cause of continual conflict. |

|

|

] inherited this great estate from ]. However, ] acted decisively to exploit the weaknesses of King John, both legally and militarily, and by 1204 had succeeded in wresting control of most of the ancient territorial possessions. The subsequent ] (1214), along with the ] (1242) and finally the ] (1324), reduced England's holdings on the continent to a few small provinces in Gascony, and the complete loss of the crown jewel of Normandy.<ref name=ehistory /> |

|

|

|

|

|

By the early 14th century, many people in the English aristocracy could still remember a time when their grandparents and great-grandparents had control over wealthy continental regions, such as Normandy, which they also considered their ancestral homeland. They were motivated to regain possession of these territories.<ref name=ehistory /> |

|

|

|

|

|

==Dynastic turmoil: 1314–1328== |

|

|

<!-- This section is linked from ] --> |

|

|

Upon the deaths of Louis X and John I, Philip IV's second-eldest son, ], sought the throne for himself. This was opposed by several of the nobility, such as ] (Joan's maternal uncle), ] (Philip's uncle) and ] (Philip's brother). However, Philip was able to negotiate them into silence; Philip's uncle and brother may have realized that this would bring them closer to the throne, while the Duke of Burgundy married Philip's eldest daughter, ]. Up until that time, all fiefs in France passed by ]; Philip had to provide some good justification why the French throne should pass in a different manner. For this, Philip exalted the throne of France to be equal to that of the ] and the ] — an office that could be entrusted to men only. The concept of ] would be invoked only much later — in the 1350s — when a Benedictine from the Abbey of St. Denis, who kept the official chronicle of the kingdom, invoked that law to strengthen the position of the King of France in his propaganda fight against Edward III of England.<ref>Jean FAVIER 1980 page 37.</ref> When Philip V himself died in 1322, his daughters, too, were put aside in favour of his brother: Charles IV, the third son of Philip IV. |

|

|

|

|

|

<center> |

|

|

<br> |

|

|

{{chart/start}} |

|

|

{{chart | | AAA | |AAA=''']'''<br>r. 1270-1285}} |

|

|

{{chart | | |)|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|.| | }} |

|

|

{{chart | | AAA | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | FFF | |AAA=''']'''<br>r. 1285-1314|FFF=]<br>d. 1325}} |

|

|

{{chart | | |)|-|-|-|v|-|-|-|v|-|-|-|.| | | | | | | |!| | }} |

|

|

{{chart | | AAA | | BBB | | CCC | | DDD |y| EEE | | FFF | |AAA=''']'''<br>r. 1314-1316|BBB=''']'''<br>r. 1316-1322|CCC=''']'''<br>r. 1322-1328|DDD=]|EEE=]|FFF=''']'''<br>r. 1328-1350}} |

|

|

{{chart | | |!| | | |!| | | | | | | | | |!| | | }} |

|

|

{{chart | | AAA | | BBB | | | | | | | | EEE | | | | | | | |AAA=]<br>b. 1312|BBB=]<br>b. 1308|EEE=]<br>b. 1312}} |

|

|

{{chart | | |!| | | |!| | | }} |

|

|

{{chart | | AAA | | BBB | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |AAA=]<br>b. 1332|BBB=]<br>b. 1323}} |

|

|

{{chart/end}} |

|

|

</center> |

|

|

|

|

|

The French nobility, however, balked at the prospect of being ruled by the king of England. Edward's ancestors, as Dukes of Aquitaine, had acquired a reputation for disobedience to the French crown, while Edward's mother, Isabella, was poorly regarded in France because of her conduct. Thus, they asserted that since the French throne could not pass to a woman, then the royal inheritance could not pass through her to her offspring. Therefore, the heir male of Philip III of France, ], was the legitimate heir in the eyes of the French. He had taken regency after Charles IV's death and was allowed to take the throne after Charles' widow gave birth to a daughter. Philip of Valois was crowned as Philip VI, the first of the ], a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. |

|

|

|

|

|

], the daughter of Louis X, also had a good legal claim to the French throne, but lacked the power to back this. The ] had no precedent against female rulers (the House of Capet having inherited it through Joan's grandmother, ]), and so by treaty she and her husband, ], were permitted to inherit that Kingdom; however, the same treaty forced Joan and her husband to accept the accession of Philip VI in France, and to surrender her hereditary French domains of Champagne and Brie to the French crown in exchange for inferior estates. Joan and Philip of Évreux then produced a son, ]. Born in 1332, Charles replaced Philip of Burgundy as Philip IV's male heir in ], and in proximity to Louis X; however, Edward remained the male heir in proximity to Saint Louis, Philip IV, and Charles IV. |

|

|

|

|

|

==Beginning of the war: 1337–1360== |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Edwardian War}} |

|

|

{{Main|Hundred Years' War (1337–1360)}} |

|

|

{{See also|War of the Breton Succession}} |

|

|

|

|

|

Open hostilities broke out as French ships began scouting coastal settlements on the ] and in 1337 Philip reclaimed the Gascon fief, citing feudal law and saying that Edward had broken his oath (a ]) by not attending to the needs and demands of his lord. Edward III responded by saying he was in fact the rightful heir to the French throne, and on ], ], ], arrived in ] with the defiance of the king of England. War had been declared. |

|

|

|

|

|

] of ], Bruge, c.1470]] |

|

|

|

|

|

In the early years of the war, Edward III allied with the nobles of the ] and the burghers of ], but after two campaigns where nothing was achieved, the alliance fell apart in 1340. The payments of subsidies to the German princes and the costs of maintaining an army abroad dragged the English government into bankruptcy, heavily damaging Edward’s prestige. At sea, France enjoyed supremacy for some time, through the use of Genoese ships and crews. Several towns on the English coast were sacked, some repeatedly. This caused fear and disruption along the English coast. There was a constant fear during this part of the war that the French would invade. France's sea power led to economic disruptions in England as it cut down on the wool trade to Flanders and the wine trade from Gascony. However, in 1340, while attempting to hinder the English army from landing, the French fleet was almost completely destroyed in the ]. After this, England was able to dominate the ] for the rest of the war, preventing French ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1341, conflict over the succession to the Duchy of ] began the ], in which Edward backed ] and Philip backed ]. Action for the next few years focused around a back and forth struggle in Brittany, with the city of ] changing hands several times, as well as further campaigns in Gascony with mixed success for both sides. |

|

|

], 1346]] |

|

|

In July 1346, Edward mounted a major invasion across the Channel, landing in the ]. The English army captured ] in just one day, surprising the French who had expected the city to hold out much longer. Philip gathered a large army to oppose Edward, who chose to march northward toward the Low Countries, pillaging as he went, rather than attempting to take and hold territory. Finding himself unable to outmanoeuvre Philip, Edward positioned his forces for battle, and Philip's army attacked. The famous ] was a complete disaster for the French, largely credited to the ]men and the French king, who allowed his army to attack before they were ready.<ref>Rogers (2000) </ref> Edward proceeded north unopposed and besieged the city of ] on the ], capturing it in 1347. This became an important strategic asset for the English. It allowed them to keep troops in France safely. Calais would remain under English control past the end of the war until 1558 (when it was retaken by the French). In the same year, an English victory against Scotland in the ] led to the capture of David II and greatly reduced the threat from Scotland. |

|

|

|

|

|

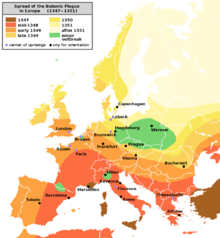

In 1348, the ] began to ravage Europe.<ref>Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. ''The Chronicles of Jean de Venette'' (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) Introduction p. 3-5.</ref> In 1356, after it had passed and England was able to recover financially, Edward's son and namesake, the ], known as the ], invaded France from Gascony, winning a great victory in the ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

After the battle of Poitiers, the french countryside was thrown into complete chaos. The looting, and pillaging by the nobles and the professional soldiery was rampant. They ravaged the countryside. The nobles gave no thought to the peasants they were supposed to protect. In 1358, the peasants rose in rebellion in what was called the ].<ref>Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. ''The Chronicles of Jean de Venette'' (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) Chpts. 1347, 1356</ref> Edward invaded France, for the third and last time, hoping to capitalise on the discontent and seize the throne, but although no French army stood against him in the field, he was unable to take ] or ] from the ], later ]. He negotiated the ] which was signed in 1360. The English came out of this phase of the war with half of Brittany, Aquitaine (about a quarter of France), Calais, Ponthieu, and about half of France's vassal states as their allies, representing the clear advantage of a united England against a generally disunified France. |

|

|

|

|

|

==First peace: 1360–1369== |

|

|

{{Main|Treaty of Brétigny}} |

|

|

{{See also|Castilian Civil War}} |

|

|

|

|

|

When John's son ], sent to the English as a hostage on John's behalf, escaped in 1362, John II chivalrously gave himself up and returned to captivity in England. He died in honourable captivity in 1364 and ] succeeded him as king of France. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Treaty of Brétigny had made Edward renounce his claim to the French crown. At the same time, it greatly expanded his territory in Aquitaine and confirmed his conquest of Calais. The ratified version, the Treaty of Calais, had one small difference: the exchange of renunciations would happen ''after'' the territorial exchanges, not immediately, as had been stated in the Treaty of Brétigny. |

|

|

|

|

|

Due to the Navarrese attacks in France, Edward III bid for more time, contemplating about demanding more territory from the French king. Charles V pacified the Navarrese king quite quickly. In time, Edward III had forgotten about the formal exchange of renunciations. However, both monarchs had de facto complied with the treaty; Edward III had stopped quartering the arms of England with the arms of France, and the agents of the French king no longer intruded in Aquitaine. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Prince of Wales, now also Prince of Aquitaine, taxed his subjects to pay for the war in Castile. Protest did not come from the people of the territories recently ceded by the French crown, but from English Gascony. Before the loss of French sovereignty, the Gascons were controlled by their duke only from afar; with its loss, the English would have tighter control over them. Thus, the Count of Armagnac protested to the liege of his lord, the King of England; but even before response could arrive, he had requested intervention from Paris. |

|

|

|

|

|

Initially, Charles V was unsure of how to accept the pleading. If he accepted, that would have been tantamount to breaking the treaty. He consulted his lawyers, his advisers. They argued that, since Edward III had failed to make the exchange of renunciations, Aquitaine was still under French suzerainty, so Charles V could legally accept the pleading. In 1369, Charles V of France declared war against Edward on the pretext that he had failed to observe the terms of the Treaty of Brétigny. |

|

|

|

|

|

==French ascendancy under Charles V: 1369–1389== |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Caroline War}} |

|

|

{{Main|Hundred Years' War (1369–1389)}} |

|

|

|

|

|

The reign of Charles V saw the English steadily pushed back. Although the Breton war ended in favour of the English at the ], the dukes of Brittany eventually reconciled with the French throne. The Breton soldier ] became one of the most successful French generals of the Hundred Years' War. |

|

|

]]] |

|

|

|

|

|

Simultaneously, the Black Prince was occupied with war in the ] from 1366 and due to illness was relieved of command in 1371, whilst Edward III was too elderly to fight; providing France with even more advantages. ], whose daughters Constance and Isabella were married to the Black Prince's brothers ] and ], was deposed by ] in 1370 with the support of Du Guesclin and the French. War erupted between Castile and France on one side and Portugal and England on the other. |

|

|

|

|

|

==Second peace: 1389–1415== |

|

|

{{See also|Civil war between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians}} |

|

|

|

|

|

England too was plagued with internal strife during this period, as ] in ] and ] were accompanied by renewed border war with Scotland and two separate civil wars. The Irish troubles embroiled much of the reign of ], who had not resolved them by the time he lost his throne and life to his cousin Henry, who took power for himself in 1399. |

|

|

|

|

|

Although ] planned campaigns in France, he was unable to put them into effect during his short reign. In the meantime, though, the French King ] was descending into madness, and an open conflict for power began between his cousin ], and his brother, ]. After Louis's assassination, the ] family took political power in opposition to John. By 1410, both sides were bidding for the help of English forces in a civil war. |

|

|

|

|

|

This was followed by the rebellion of ] in Wales, which was not finally put down until 1415 and actually resulted in Welsh semi-independence for a number of years. In Scotland, the change in regime in England prompted a fresh series of border raids which were countered by an invasion in 1402 and the defeat of a Scottish army at the ]. A dispute over the spoils of this action between Henry and the ] resulted in a long and bloody struggle between the two for control of northern England, which was resolved only with the almost complete destruction of the Percy family by 1408. Throughout this period, England was also faced with repeated raids by French and Scandinavian ], which heavily damaged trade and the navy. These problems accordingly delayed any resurgence of the dispute with France until 1415. |

|

|

|

|

|

==Resumption of the war under Henry V: 1415–1429== |

|

|

{{Campaignbox Lancastrian War}} |

|

|

{{Main|Hundred Years' War (1415–1453)}} |

|

|

The final phase of warmaking that engulfed France between 1415 and 1435 is the most famous phase of the Hundred Years' War. Plans had been laid for the declaration of war since the rise to the throne of Henry IV, in 1399. However, it was his son, ], who was finally given the opportunity. In 1414, Henry turned down an Armagnac offer to restore the Brétigny frontiers in return for his support. Instead, he demanded a return to the territorial status during the reign of ]. In August 1415, he landed with an army at ] and took it, although the city resisted for longer than expected. This meant that by the time he came to marching farther, most of the campaign season was gone. Although tempted to march on Paris directly, he elected to make a raiding expedition across France toward English-occupied Calais. In a campaign reminiscent of ], he found himself outmanoeuvred and low on supplies, and had to make a stand against a much larger French army at the ], north of the ]. In spite of his disadvantages, his victory was near-total; the French defeat was catastrophic, with the loss of many of the Armagnac leaders. About 40% of the French nobility was lost at Agincourt<ref name="population"/> after Henry ordered the killing of the prisoners |

|

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

Henry took much of Normandy, including ] in 1417 and ] on January 19, 1419, making Normandy English for the first time in two centuries. He made formal alliance with the ], who had taken Paris, after the assassination of Duke ] in 1419. In 1420, Henry met with the mad king ], who signed the ], by which Henry would marry Charles' daughter ] and Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France. The Dauphin, ], was declared illegitimate. Henry formally entered Paris later that year and the agreement was ratified by the ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

Henry's progress was now stopped by the arrival in France of a Scottish army of around 6,000 men. In 1421, a combined Franco-Scottish force led by ] crushed a larger English army at the ], killing the English commander, Thomas, 1st Duke of Clarence, and killing or capturing most of the English leaders. The French were so grateful that Buchan was immediately promoted to the office of High Constable of France. Soon after the Battle of Bauge Henry V died at ] in 1422. Soon after that, Charles too had died. Henry's infant son, ], was immediately crowned king of England and France, but the Armagnacs remained loyal to Charles' son and the war continued in central France. |

|

|

|

|

|

The English continued to attack France and in 1429 were besieging the important French city of Orleans. An attack on an English supply convoy led to the skirmish that is now known as ] when ] circled his supply wagons (largely filled with herring) around his archers and repelled a few hundred attackers. Later that year, a French saviour appeared in the form of a peasant girl from ] named ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

==French victory: 1429–1453== |

|

|

] |

|

|

By 1424, the uncles of Henry VI had begun to quarrel over the infant's regency, and one, ], married ], ], and invaded ] to regain her former dominions, bringing him into direct conflict with ], ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

By 1428, the English were ready to pursue the war again, laying ] to ]. Their force was insufficient to fully ] the city, but larger French forces remained passive. In 1429, ] convinced the ] to send her to the siege, saying she had received visions from ] telling her to drive out the English. She raised the morale of the local troops and they attacked the English ]s, forcing the English to lift the siege. Inspired by Joan, the French took several English strong points on the Loire. Shortly afterwards, a French army, some 8000 strong, broke through English archers at ] with 1500 heavy cavalry, defeating a 3000-strong army commanded by ] and ]. This victory opened the way for the Dauphin to march to ] for his coronation as Charles VII. |

|

|

|

|

|

After Joan was captured by the Burgundians in 1430 and later sold to the English, tried by an ecclesiastic court, and executed, the French advance stalled in negotiations. But, in 1435, the Burgundians under Philip III switched sides, signing the ] and returning Paris to the King of France. Burgundy's allegiance remained fickle, but their focus on expanding their domains into the Low Countries left them little energy to intervene in France. The long truces that marked the war also gave Charles time to reorganise his army and government, replacing his feudal levies with a more modern professional army that could put its superior numbers to good use, and centralising the French state. |

|

|

] (1450)]] |

|

|

A repetition of Du Guesclin's battle avoidance strategy paid dividends and the French were able to recover town after town. |

|

|

|

|

|

By 1449, the French had retaken ], and in 1450 the ] and Arthur de Richemont, Earl of Richmond, of the Montfort family (the future ]) caught an English army attempting to relieve Caen at the ] and defeated it, the English army having been attacked from the flank and rear by Richemont's force just as they were on the verge of beating Clermont's army. The French proceeded to capture ] on July 6 and ] and ] in 1451. The attempt by Talbot to retake Gascony, though initially welcomed by the locals, was crushed by ] and his cannon at the ] in 1453 where Talbot had led a small Anglo-Gascon force in a frontal attack on an entrenched camp. This is considered the last battle of the Hundred Years' War. |

|

|

|

|

|

== |

|

|

|

|

|

|

==Timeline== |

|

==Timeline== |

The war also stimulated nationalistic sentiment. It devastated France as a land, but it also awakened French nationalism. The Hundred Years' War accelerated the process of transforming France from a feudal monarchy to a centralised state. The conflict became one of not just English and French kings but one between the English and French peoples. There were constant rumours in England that the French meant to invade and destroy the English language. National feeling that emerged out of such rumours unified both France and England further. The Hundred Years War basically confirmed the fall of the French language in England, which had served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce there from the time of the Norman conquest until 1362.

Lowe (1997) argues that opposition to the war helped to shape England's early modern political culture. Although anti-war and pro-peace spokesmen generally failed to influence outcomes at the time, they had a long-term impact. England showed decreasing enthusiasm for a conflict deemed not in the national interest, yielding only losses in return for the economic burdens it imposed. In comparing this English cost-benefit analysis with French attitudes, given that both countries suffered from weak leaders and undisciplined soldiers, Lowe notes that the French understood that warfare was necessary to expel the foreigners occupying their homeland. Furthermore French kings found alternative ways to finance the war - sales taxes, debasing the coinage - and were less dependent than the English on tax levies passed by national legislatures. English anti-war critics thus had more to work with than the French.