| Revision as of 11:58, 8 August 2012 editSigiheri (talk | contribs)428 editsm ~~~~← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:49, 8 August 2012 edit undoByelf2007 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,281 edits more logical order/consistent with other articles (we need to know what it is before we go into etymology/history)Next edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| Early corporations were established by charter (i.e. by an ''ad hoc'' act granted by a monarch or passed by a parliament or legislature). Most jurisdictions now allow the creation of new corporations through registration. In addition to legal personality, registered companies tend to have ], be owned by ]s<ref>{{cite book |title=Company Law |last1=Pettet |first1=B. G. |publisher=Pearson Education |year=2005 |page=151 |quote=Reading the above, makes it possible to forget that the shareholders are the ''owners'' of the company.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Law of Private Companies |first1=Thomas B. |last1=Courtney |publisher=Bloomsbury Professional |year=2002 |edition=2nd |at=4.001 |quote=As a corporation, or body corporate, a private company is regarded in law as having a separate legal personality from its shareholders (owners) and directors (managers).}}</ref> who can transfer their ]s to others, and controlled by a ] who the shareholders appoint. | Early corporations were established by charter (i.e. by an ''ad hoc'' act granted by a monarch or passed by a parliament or legislature). Most jurisdictions now allow the creation of new corporations through registration. In addition to legal personality, registered companies tend to have ], be owned by ]s<ref>{{cite book |title=Company Law |last1=Pettet |first1=B. G. |publisher=Pearson Education |year=2005 |page=151 |quote=Reading the above, makes it possible to forget that the shareholders are the ''owners'' of the company.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Law of Private Companies |first1=Thomas B. |last1=Courtney |publisher=Bloomsbury Professional |year=2002 |edition=2nd |at=4.001 |quote=As a corporation, or body corporate, a private company is regarded in law as having a separate legal personality from its shareholders (owners) and directors (managers).}}</ref> who can transfer their ]s to others, and controlled by a ] who the shareholders appoint. | ||

| == |

==Types== | ||

| :''For a list of types of corporation and other business types by country, see ].'' | |||

| {{Main|History of corporations|List of oldest companies}} | |||

| ] mine, dated June 16, 1288.]] | |||

| The word "corporation" derives from ''corpus'', the ] word for body, or a "body of people." By the time of ] (reigned 527-565), ] recognized a range of corporate entities under the names ''universitas'', ''corpus'' or ''collegium''. These included the state itself (the ''populus Romanus''), municipalities, and such private associations as sponsors of a ], burial clubs, political groups, and guilds of craftsmen or traders. Such bodies commonly had the right to own property and make contracts, to receive gifts and legacies, to sue and be sued, and, in general, to perform legal acts through representatives. Private associations were granted designated privileges and liberties by the emperor.<ref>Harold Joseph Berman, ''Law and Revolution'' (vol. 1)'': The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition'', Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, pp. 215-16. ISBN 0674517768</ref> Entities which carried on business and were the subjects of legal rights were found in ], and the ] in ancient India.<ref>Vikramaditya S. Khanna (2005). ].</ref> In medieval Europe, churches became incorporated, as did local governments, such as the ] and the ]. The point was that the incorporation would survive longer than the lives of any particular member, existing in perpetuity. The alleged oldest commercial corporation in the world, the ] mining community in ], ], obtained a ] from King ] in 1347. Many European nations chartered corporations to lead colonial ventures, such as the ] or the ], and these corporations came to play a large part in the history of ]. | |||

| Depending on the jurisdiction, there are four types of corporations, of which a particular jurisdiction will allow two of them. The types of corporations which a jurisdiction will charter either are for-profit corporations and not-for-profit corporations, or it will charter stock corporations and non-stock corporations. The main difference is that a corporation that is for profit is usually a stock corporation, but can be a non-stock corporation, but a not-for-profit corporation is usually a non-stock corporation. There are certain states which do allow a non-profit corporation to issue stock, including Kansas, Delaware, and Michigan.<ref name="HopkinsGross2009">{{cite book|author1=Bruce R. Hopkins|author2=Virginia C. Gross|title=Nonprofit Governance: Law, Practices, and Trends|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Lir1HW3Aj8AC&pg=PA101|accessdate=9 May 2012|date=2 June 2009|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-470-35804-7|pages=101–}}</ref> Generally these states allow the stock for purposes of control of the non-profit corporation but allow no dividends. | |||

| During the time of colonial expansion in the 17th century, the true progenitors of the modern corporation emerged as the "chartered company". Acting under a charter sanctioned by the Dutch government, the ] (VOC) defeated ] forces and established itself in the ] in order to profit from the ]an demand for ]. Investors in the VOC were issued paper certificates as proof of share ownership, and were able to trade their shares on the original ] stock exchange. Shareholders are also explicitly granted ] in the company's royal charter.<ref>Om Prakash, ''European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India'' (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998).</ref> In the late 18th century, ], the author of the first treatise on ] in English, defined a corporation as, | |||

| Most corporations are registered with the local jurisdiction as either a stock corporation or a non-stock corporation. Stock corporations sell stock to generate capital. A stock corporation must always be a for-profit corporation. A ] cannot have stockholders, but may have members who have voting rights in the corporation. | |||

| {{quote|a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having ] under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual, particularly of taking and granting property, of contracting obligations, and of suing and being sued, of enjoying privileges and immunities in common, and of exercising a variety of political rights, more or less extensive, according to the design of its institution, or the powers conferred upon it, either at the time of its creation, or at any subsequent period of its existence.|A Treatise on the Law of Corporations, Stewart Kyd (1793-1794)}} | |||

| Some jurisdictions (], for example) separate corporations into for-profit and non-profit, as opposed to dividing into stock and non-stock. | |||

| === Mercantilism === | |||

| {{See also|Mercantilism|South Sea Bubble}} | |||

| Several states also allow a variation of the corporation for use by professionals (i.e., those individuals typically considered as professionals who require a license from the state to conduct business). In some states, such as , these corporations are known as "professional corporations". A professional corporation will always be a for-profit corporation. | |||

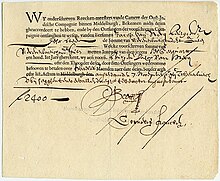

| ] issued by the ], dating from 1623, for the amount of 2,400 florins]] | |||

| ===For-profit and non-profit=== | |||

| Labeled by both contemporaries and historians as "the grandest society of merchants in the universe", the ] would come to symbolize the dazzlingly rich potential of the corporation, as well as new methods of business that could be both brutal and exploitative.<ref>John Keay, ''The Honorable Company: A History of the English East India Company'' (MacMillan, New York 1991).</ref> On 31 December 1600, the ] granted the company a 15-year monopoly on trade to and from the ] and ]. By 1611, shareholders in the East India Company were earning an almost 150% ]. Subsequent stock offerings demonstrated just how lucrative the Company had become. Its first stock offering in 1613-1616 raised £418,000, and its first offering in 1617-1622 raised £1.6 million.<ref>''Ibid. '' at 113.</ref> | |||

| {{Main|non-profit organization}} | |||

| Corporate entities may be formed for either profit- or not-for-profit (also called non-profit) purposes. Many non-profit corporations are also tax-exempt (such as charities), which means the corporation's income is not taxed under federal or state law or both. | |||

| In the ], government chartering began to fall out of vogue in the mid-19th century. Corporate law at the time was focused on protection of the public interest, and not on the interests of corporate shareholders. Corporate charters were closely regulated by the states. Forming a corporation usually required an act of legislature. Investors generally had to be given an equal say in corporate governance, and corporations were required to comply with the purposes expressed in their charters. Many private firms in the 19th century avoided the corporate model for these reasons (] formed his steel operation as a ], and ] set up ] as a ]). Eventually, state governments began to realize the greater corporate registration revenues available by providing more permissive corporate laws. ] was the first state to adopt an "enabling" corporate law, with the goal of attracting more business to the state.<ref></ref> ] followed, and soon became known as the most corporation-friendly state in the country after New Jersey raised taxes on the corporations, driving them out. New Jersey reduced these taxes after this mistake was realized, but by then it was too late; even today, most major public corporations in the United States are set up under Delaware law. | |||

| Different principles of ] apply to a wide variety of business and ] activities. Although the laws governing these creatures of ] differ between various types of entities, many of the principles and rules that govern profit-making enterprises also apply to non-profit organizations — as the underlying structures of these two types of entity often resemble each other. | |||

| By the beginning of the 19th century, government policy on both sides of the Atlantic began to change, reflecting the growing popularity of the proposition that corporations were riding the economic wave of the future. In 1819, the U. S. Supreme Court granted corporations a plethora of rights they had not previously recognized or enjoyed.<ref>'']'', 17 U. S. 518 (1819).</ref> Corporate charters were deemed "inviolable", and not subject to arbitrary amendment or abolition by state governments.<ref>''Id. '' at 25.</ref> The Corporation as a whole was labeled an "artificial person", possessing both individuality and immortality.<ref>''Id. '' at 45.</ref> | |||

| ===Closely held corporations and publicly traded corporations=== | |||

| At around the same time, British legislation was similarly freeing the corporation from historical restrictions. In 1844 the ] passed the Joint Stock Companies Act, which allowed companies to incorporate without a royal charter or an Act of Parliament.<ref>Sean M. O'Connor, ''Be Careful What You Wish For: How Accountants and Congress Created the Problem of Auditor Independence'', 45 B. C. L. Rev. 741, 749 (2004).</ref> Ten years later, ], the key provision of modern corporate law, passed into English law: in response to increasing pressure from newly emerging capital interests, Parliament passed the ], which established the principle that any corporation could enjoy limited legal liability on both contract and tort claims simply by registering as a "limited" company with the appropriate government agency.<ref>Limited Liability Act, 18 & 19 Vict., ch. 133 (1855)(Eng.), cited in Paul G. Mahoney, ''Contract or Concession? An Essay on the History of Corporate Law'', 34 Ga. L. Rev. 873, 892 (2000).</ref> | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=November 2009}} | |||

| The institution most often referenced by the word "corporation" is a '''publicly traded''' corporation, the shares of which are traded on a public stock exchange (for example, the ] or ] in the United States) where shares of stock of corporations are bought and sold by and to the general public. Most of the largest businesses in the world are publicly traded corporations. However, the majority of corporations are said to be '''closely held''', '''privately held''' or '''close corporations''', meaning that no ready market exists for the trading of shares. Many such corporations are owned and managed by a small group of businesspeople or companies, although the size of such a corporation can be as vast as the largest public corporations. | |||

| Closely held corporations do have some advantages over publicly traded corporations. A small, closely held company can often make company-changing decisions much more rapidly than a publicly traded company. A publicly traded company is also at the mercy of the market, having capital flow in and out based not only on what the company is doing but also on what the market and even what the competitors are doing. Publicly traded companies also have advantages over their closely held counterparts. Publicly traded companies often have more ] and can delegate debt throughout all shareholders. This means that people invested in a publicly traded company will each take a much smaller hit to their own capital as opposed to those involved with a closely held corporation. Publicly traded companies though suffer from this exact advantage. A closely held corporation can often voluntarily take a hit to profit with little to no repercussions (as long as it is not a sustained loss). A publicly traded company though often comes under extreme scrutiny if profit and growth are not evident to stock holders, thus stock holders may sell, further damaging the company. Often this blow is enough to make a small public company fail. | |||

| This prompted the English periodical '']'' to write in 1855 that "never, perhaps, was a change so vehemently and generally demanded, of which the importance was so much overrated. "<ref>Graeme G. Acheson & John D. Turner, ''The Impact of Limited Liability on Ownership and Control: Irish Banking, 1877-1914'', School of Management and Economics, Queen's University of Belfast, available at and .</ref> The glaring inaccuracy of the second part of this judgment was recognized by the same magazine more than 70 years later, when it claimed that, "he economic historian of the future. . . may be inclined to assign to the nameless inventor of the principle of limited liability, as applied to trading corporations, a place of honour with ] and ], and other pioneers of the ]. "<ref>''Economist'', December 18, 1926, at 1053, as quoted in Mahoney, ''supra'', at 875.</ref> | |||

| Often communities benefit from a closely held company more so than from a public company. A closely held company is far more likely to stay in a single place that has treated them well, even if going through hard times. The shareholders can incur some of the damage the company may receive from a bad year or slow period in the company profits. Closely held companies often have a better relationship with workers. In larger, publicly traded companies, often when a year has gone badly the first area to feel the effects are the work force with lay offs or worker hours, wages or benefits being cut. Again, in a closely held business the shareholders can incur this profit damage rather than passing it to the workers. | |||

| ===Modern corporations=== | |||

| By the end of the 19th century the ], New Jersey allowing ], and ] resulted in larger corporations with dispersed shareholders. (See ] <ref>For a comparison of the differences between the "Classic Corporation" (before 1860) and the "Modern Corporation" (after 1900), see Ted Nace, ''Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of Democracy'' 71 (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco 2003).</ref> The well-known '']'' decision began to influence policymaking and the modern corporate era had begun. | |||

| The affairs of publicly traded and ]s are similar in many respects. The main difference in most countries is that publicly traded corporations have the burden of complying with additional securities laws, which (especially in the U.S.) may require additional periodic disclosure (with more stringent requirements), stricter corporate governance standards, and additional procedural obligations in connection with major corporate transactions (for example, mergers) or events (for example, elections of directors). | |||

| The 20th century saw a proliferation of enabling law across the world, which helped to drive economic booms in many countries before and after World War I. Starting in the 1980s, many countries with large state-owned corporations moved toward ], the selling of publicly owned services and enterprises to corporations. ] (reducing the regulation of corporate activity) often accompanied privatization as part of a ] policy. Another major postwar shift was toward the development of ], in which large corporations purchased smaller corporations to expand their industrial base. Japanese firms developed a horizontal conglomeration model, the ], which was later duplicated in other countries as well.<ref>Apple</ref> | |||

| A closely held corporation may be a ] of another corporation (its ]), which may itself be either a closely held or a public corporation. In some jurisdictions, the subsidiary of a listed public corporation is also defined as a public corporation (for example, ]). | |||

| ===Benefit corporation=== | |||

| {{Main|Benefit corporation}} | |||

| A benefit corporation, or in short-hand a B corporation, is a class of corporation required by law to create general benefit for society as well as for shareholders. Benefit Corporations must create a material positive impact on society, and consider how their decisions affect their employees, community, and the environment. Moreover, they must publicly report on their social and environmental performances using established third-party standards.<ref name=maryland>{{cite web|title=Maryland First State in Union to Pass Benefit Corporation Legislation|url=http://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/29332-Maryland-First-State-in-Union-to-Pass-Benefit-Corporation-Legislation|publisher=]|date=14 April 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The chartering of Benefit Corporations is an attempt to reclaim the original purpose for which corporations were chartered in early America. Then, states chartered corporations to achieve a specific public purpose, such as building bridges or roads. Their legitimacy stemmed from their delegated charter, although they could still earn profits while fulfilling it. | |||

| Over time, however, corporations came to be chartered without any public purpose, while being legally bound to the singular purpose of profit-maximization for its shareholders. Advocates of Benefit Corporations assert that this singular focus has resulted in a variety of societal ills, including the thwarting of democracy, diminished social good, and negative environmental impacts.<ref name=raskin>Raskin, Jamie. "The Rise of Benefit Corporations", ''The Nation'', 2011 June 8. Available at http://www.thenation.com/article/161261/rise-benefit-corporations</ref> | |||

| In April 2010, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass Benefit Corporation legislation. Hawaii, Virginia, California, Vermont, and New Jersey soon followed. Additionally, as of November 2011, Benefit Corporation legislation had been introduced or partially passed in Colorado, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.<ref>B Corp Legislation. Available at http://www.bcorporation.net/publicpolicy. Also see {{cite news|url=http://www.bizjournals.com/baltimore/stories/2010/10/04/daily18.html|title=Md. 'becoming the Delaware of benefit corporations'|publisher=]|date=5 October 2010}}, {{cite web|url=http://www.care2.com/causes/new-jersey-b-corporation-bill-passes-legislature-heads-to-governor-for-signature.html|title=New Jersey B Corporation Bill Passes Legislature; Heads to Governor for Signature|publisher=Care2|date=13 January 2011}}, {{cite web|url=http://www.buffalorising.com/2011/06/new-york-state-senate-and-assembly-pass-benefit-corporation-legislation.html|title=New York State Senate and Assembly Pass Benefit Corporation Legislation|publisher=Buffalo Rising|date=28 June 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Benefit Corporation laws address concerns held by entrepreneurs who wish to raise growth capital but fear losing control of the social or environmental mission of their business. In addition, the laws provide companies the ability to consider factors other than the highest purchase offer at the time of sale, in spite of the ruling on ]. Chartering as a Benefit Corporation also allows companies to distinguish themselves as businesses with a social conscience, and as one that aspires to a standard they consider higher than mere profit-maximization for shareholders.<ref> article by Gar Alperovitz, also appeared in the June 13, 2011 edition of '']''</ref> | |||

| ===Mutual benefit corporations===<!-- ] links to here --> | |||

| A mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a corporation formed in the United States solely for the benefit of its members. An example of a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a golf club. Individuals pay to join the club, memberships may be bought and sold, and any property owned by the club is distributed to its members if the club dissolves. The club can decide, in its corporate bylaws, how many members to have, and who can be a member. Generally, while it is a nonprofit corporation, a mutual benefit corporation is not a charity. Because it is not a charity, a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation cannot obtain 501(c)(3) status. If there is a dispute as to how a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is being operated, it is up to the members to resolve the dispute since the corporation exists to solely serve the needs of its membership and not the general public.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Corporate law== | ==Corporate law== | ||

| Line 90: | Line 106: | ||

| The law differs among jurisdictions, and is in a state of flux. Some argue that shareholders should be ultimately responsible in such circumstances, forcing them to consider issues other than profit when investing, but a corporation may have millions of small shareholders who know nothing about its business activities. Moreover, traders — especially ]s — may turn over shares in corporations many times a day.<ref>See, for example, the Ontario's Environmental Protection Act.</ref> The issue of corporate repeat offenders (see H. Glasbeek, "Wealth by Stealth: Corporate Crime, Corporate Law, and the Perversion of Democracy", ISBN 978-1-896357-41-6, Between the Lines Press: Toronto 2002) raises the question of the so-called "death penalty for corporations."<ref></ref> | The law differs among jurisdictions, and is in a state of flux. Some argue that shareholders should be ultimately responsible in such circumstances, forcing them to consider issues other than profit when investing, but a corporation may have millions of small shareholders who know nothing about its business activities. Moreover, traders — especially ]s — may turn over shares in corporations many times a day.<ref>See, for example, the Ontario's Environmental Protection Act.</ref> The issue of corporate repeat offenders (see H. Glasbeek, "Wealth by Stealth: Corporate Crime, Corporate Law, and the Perversion of Democracy", ISBN 978-1-896357-41-6, Between the Lines Press: Toronto 2002) raises the question of the so-called "death penalty for corporations."<ref></ref> | ||

| == |

==History== | ||

| {{Main|History of corporations|List of oldest companies}} | |||

| :''For a list of types of corporation and other business types by country, see ].'' | |||

| ] mine, dated June 16, 1288.]] | |||

| The word "corporation" derives from ''corpus'', the ] word for body, or a "body of people." By the time of ] (reigned 527-565), ] recognized a range of corporate entities under the names ''universitas'', ''corpus'' or ''collegium''. These included the state itself (the ''populus Romanus''), municipalities, and such private associations as sponsors of a ], burial clubs, political groups, and guilds of craftsmen or traders. Such bodies commonly had the right to own property and make contracts, to receive gifts and legacies, to sue and be sued, and, in general, to perform legal acts through representatives. Private associations were granted designated privileges and liberties by the emperor.<ref>Harold Joseph Berman, ''Law and Revolution'' (vol. 1)'': The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition'', Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, pp. 215-16. ISBN 0674517768</ref> Entities which carried on business and were the subjects of legal rights were found in ], and the ] in ancient India.<ref>Vikramaditya S. Khanna (2005). ].</ref> In medieval Europe, churches became incorporated, as did local governments, such as the ] and the ]. The point was that the incorporation would survive longer than the lives of any particular member, existing in perpetuity. The alleged oldest commercial corporation in the world, the ] mining community in ], ], obtained a ] from King ] in 1347. Many European nations chartered corporations to lead colonial ventures, such as the ] or the ], and these corporations came to play a large part in the history of ]. | |||

| During the time of colonial expansion in the 17th century, the true progenitors of the modern corporation emerged as the "chartered company". Acting under a charter sanctioned by the Dutch government, the ] (VOC) defeated ] forces and established itself in the ] in order to profit from the ]an demand for ]. Investors in the VOC were issued paper certificates as proof of share ownership, and were able to trade their shares on the original ] stock exchange. Shareholders are also explicitly granted ] in the company's royal charter.<ref>Om Prakash, ''European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India'' (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998).</ref> In the late 18th century, ], the author of the first treatise on ] in English, defined a corporation as, | |||

| Depending on the jurisdiction, there are four types of corporations, of which a particular jurisdiction will allow two of them. The types of corporations which a jurisdiction will charter either are for-profit corporations and not-for-profit corporations, or it will charter stock corporations and non-stock corporations. The main difference is that a corporation that is for profit is usually a stock corporation, but can be a non-stock corporation, but a not-for-profit corporation is usually a non-stock corporation. There are certain states which do allow a non-profit corporation to issue stock, including Kansas, Delaware, and Michigan.<ref name="HopkinsGross2009">{{cite book|author1=Bruce R. Hopkins|author2=Virginia C. Gross|title=Nonprofit Governance: Law, Practices, and Trends|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Lir1HW3Aj8AC&pg=PA101|accessdate=9 May 2012|date=2 June 2009|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-470-35804-7|pages=101–}}</ref> Generally these states allow the stock for purposes of control of the non-profit corporation but allow no dividends. | |||

| {{quote|a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having ] under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual, particularly of taking and granting property, of contracting obligations, and of suing and being sued, of enjoying privileges and immunities in common, and of exercising a variety of political rights, more or less extensive, according to the design of its institution, or the powers conferred upon it, either at the time of its creation, or at any subsequent period of its existence.|A Treatise on the Law of Corporations, Stewart Kyd (1793-1794)}} | |||

| Most corporations are registered with the local jurisdiction as either a stock corporation or a non-stock corporation. Stock corporations sell stock to generate capital. A stock corporation must always be a for-profit corporation. A ] cannot have stockholders, but may have members who have voting rights in the corporation. | |||

| === Mercantilism === | |||

| Some jurisdictions (], for example) separate corporations into for-profit and non-profit, as opposed to dividing into stock and non-stock. | |||

| {{See also|Mercantilism|South Sea Bubble}} | |||

| ] issued by the ], dating from 1623, for the amount of 2,400 florins]] | |||

| Several states also allow a variation of the corporation for use by professionals (i.e., those individuals typically considered as professionals who require a license from the state to conduct business). In some states, such as , these corporations are known as "professional corporations". A professional corporation will always be a for-profit corporation. | |||

| Labeled by both contemporaries and historians as "the grandest society of merchants in the universe", the ] would come to symbolize the dazzlingly rich potential of the corporation, as well as new methods of business that could be both brutal and exploitative.<ref>John Keay, ''The Honorable Company: A History of the English East India Company'' (MacMillan, New York 1991).</ref> On 31 December 1600, the ] granted the company a 15-year monopoly on trade to and from the ] and ]. By 1611, shareholders in the East India Company were earning an almost 150% ]. Subsequent stock offerings demonstrated just how lucrative the Company had become. Its first stock offering in 1613-1616 raised £418,000, and its first offering in 1617-1622 raised £1.6 million.<ref>''Ibid. '' at 113.</ref> | |||

| ===For-profit and non-profit=== | |||

| {{Main|non-profit organization}} | |||

| In the ], government chartering began to fall out of vogue in the mid-19th century. Corporate law at the time was focused on protection of the public interest, and not on the interests of corporate shareholders. Corporate charters were closely regulated by the states. Forming a corporation usually required an act of legislature. Investors generally had to be given an equal say in corporate governance, and corporations were required to comply with the purposes expressed in their charters. Many private firms in the 19th century avoided the corporate model for these reasons (] formed his steel operation as a ], and ] set up ] as a ]). Eventually, state governments began to realize the greater corporate registration revenues available by providing more permissive corporate laws. ] was the first state to adopt an "enabling" corporate law, with the goal of attracting more business to the state.<ref></ref> ] followed, and soon became known as the most corporation-friendly state in the country after New Jersey raised taxes on the corporations, driving them out. New Jersey reduced these taxes after this mistake was realized, but by then it was too late; even today, most major public corporations in the United States are set up under Delaware law. | |||

| Corporate entities may be formed for either profit- or not-for-profit (also called non-profit) purposes. Many non-profit corporations are also tax-exempt (such as charities), which means the corporation's income is not taxed under federal or state law or both. | |||

| By the beginning of the 19th century, government policy on both sides of the Atlantic began to change, reflecting the growing popularity of the proposition that corporations were riding the economic wave of the future. In 1819, the U. S. Supreme Court granted corporations a plethora of rights they had not previously recognized or enjoyed.<ref>'']'', 17 U. S. 518 (1819).</ref> Corporate charters were deemed "inviolable", and not subject to arbitrary amendment or abolition by state governments.<ref>''Id. '' at 25.</ref> The Corporation as a whole was labeled an "artificial person", possessing both individuality and immortality.<ref>''Id. '' at 45.</ref> | |||

| Different principles of ] apply to a wide variety of business and ] activities. Although the laws governing these creatures of ] differ between various types of entities, many of the principles and rules that govern profit-making enterprises also apply to non-profit organizations — as the underlying structures of these two types of entity often resemble each other. | |||

| At around the same time, British legislation was similarly freeing the corporation from historical restrictions. In 1844 the ] passed the Joint Stock Companies Act, which allowed companies to incorporate without a royal charter or an Act of Parliament.<ref>Sean M. O'Connor, ''Be Careful What You Wish For: How Accountants and Congress Created the Problem of Auditor Independence'', 45 B. C. L. Rev. 741, 749 (2004).</ref> Ten years later, ], the key provision of modern corporate law, passed into English law: in response to increasing pressure from newly emerging capital interests, Parliament passed the ], which established the principle that any corporation could enjoy limited legal liability on both contract and tort claims simply by registering as a "limited" company with the appropriate government agency.<ref>Limited Liability Act, 18 & 19 Vict., ch. 133 (1855)(Eng.), cited in Paul G. Mahoney, ''Contract or Concession? An Essay on the History of Corporate Law'', 34 Ga. L. Rev. 873, 892 (2000).</ref> | |||

| ===Closely held corporations and publicly traded corporations=== | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=November 2009}} | |||

| The institution most often referenced by the word "corporation" is a '''publicly traded''' corporation, the shares of which are traded on a public stock exchange (for example, the ] or ] in the United States) where shares of stock of corporations are bought and sold by and to the general public. Most of the largest businesses in the world are publicly traded corporations. However, the majority of corporations are said to be '''closely held''', '''privately held''' or '''close corporations''', meaning that no ready market exists for the trading of shares. Many such corporations are owned and managed by a small group of businesspeople or companies, although the size of such a corporation can be as vast as the largest public corporations. | |||

| This prompted the English periodical '']'' to write in 1855 that "never, perhaps, was a change so vehemently and generally demanded, of which the importance was so much overrated. "<ref>Graeme G. Acheson & John D. Turner, ''The Impact of Limited Liability on Ownership and Control: Irish Banking, 1877-1914'', School of Management and Economics, Queen's University of Belfast, available at and .</ref> The glaring inaccuracy of the second part of this judgment was recognized by the same magazine more than 70 years later, when it claimed that, "he economic historian of the future. . . may be inclined to assign to the nameless inventor of the principle of limited liability, as applied to trading corporations, a place of honour with ] and ], and other pioneers of the ]. "<ref>''Economist'', December 18, 1926, at 1053, as quoted in Mahoney, ''supra'', at 875.</ref> | |||

| Closely held corporations do have some advantages over publicly traded corporations. A small, closely held company can often make company-changing decisions much more rapidly than a publicly traded company. A publicly traded company is also at the mercy of the market, having capital flow in and out based not only on what the company is doing but also on what the market and even what the competitors are doing. Publicly traded companies also have advantages over their closely held counterparts. Publicly traded companies often have more ] and can delegate debt throughout all shareholders. This means that people invested in a publicly traded company will each take a much smaller hit to their own capital as opposed to those involved with a closely held corporation. Publicly traded companies though suffer from this exact advantage. A closely held corporation can often voluntarily take a hit to profit with little to no repercussions (as long as it is not a sustained loss). A publicly traded company though often comes under extreme scrutiny if profit and growth are not evident to stock holders, thus stock holders may sell, further damaging the company. Often this blow is enough to make a small public company fail. | |||

| ===Modern corporations=== | |||

| Often communities benefit from a closely held company more so than from a public company. A closely held company is far more likely to stay in a single place that has treated them well, even if going through hard times. The shareholders can incur some of the damage the company may receive from a bad year or slow period in the company profits. Closely held companies often have a better relationship with workers. In larger, publicly traded companies, often when a year has gone badly the first area to feel the effects are the work force with lay offs or worker hours, wages or benefits being cut. Again, in a closely held business the shareholders can incur this profit damage rather than passing it to the workers. | |||

| By the end of the 19th century the ], New Jersey allowing ], and ] resulted in larger corporations with dispersed shareholders. (See ] <ref>For a comparison of the differences between the "Classic Corporation" (before 1860) and the "Modern Corporation" (after 1900), see Ted Nace, ''Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of Democracy'' 71 (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco 2003).</ref> The well-known '']'' decision began to influence policymaking and the modern corporate era had begun. | |||

| The 20th century saw a proliferation of enabling law across the world, which helped to drive economic booms in many countries before and after World War I. Starting in the 1980s, many countries with large state-owned corporations moved toward ], the selling of publicly owned services and enterprises to corporations. ] (reducing the regulation of corporate activity) often accompanied privatization as part of a ] policy. Another major postwar shift was toward the development of ], in which large corporations purchased smaller corporations to expand their industrial base. Japanese firms developed a horizontal conglomeration model, the ], which was later duplicated in other countries as well.<ref>Apple</ref> | |||

| The affairs of publicly traded and ]s are similar in many respects. The main difference in most countries is that publicly traded corporations have the burden of complying with additional securities laws, which (especially in the U.S.) may require additional periodic disclosure (with more stringent requirements), stricter corporate governance standards, and additional procedural obligations in connection with major corporate transactions (for example, mergers) or events (for example, elections of directors). | |||

| ==Corporate taxation== | |||

| A closely held corporation may be a ] of another corporation (its ]), which may itself be either a closely held or a public corporation. In some jurisdictions, the subsidiary of a listed public corporation is also defined as a public corporation (for example, ]). | |||

| {{Main|Corporate tax}} | |||

| In many countries corporate profits are taxed at a corporate tax rate, and dividends paid to shareholders are taxed at a separate rate. Such a system is sometimes referred to as "]", because any profits distributed to shareholders will eventually be taxed twice. One solution to this (as in the case of the Australian and UK tax systems) is for the recipient of the dividend to be entitled to a tax credit which addresses the fact that the profits represented by the dividend have already been taxed. The company profit being passed on is therefore effectively only taxed at the rate of tax paid by the eventual recipient of the dividend. In other systems, dividends are taxed at a lower rate than other income (for example, in the US) or shareholders are taxed directly on the corporation's profits and dividends are not taxed (for example, ]s in the US). | |||

| ===Benefit corporation=== | |||

| {{Main|Benefit corporation}} | |||

| A benefit corporation, or in short-hand a B corporation, is a class of corporation required by law to create general benefit for society as well as for shareholders. Benefit Corporations must create a material positive impact on society, and consider how their decisions affect their employees, community, and the environment. Moreover, they must publicly report on their social and environmental performances using established third-party standards.<ref name=maryland>{{cite web|title=Maryland First State in Union to Pass Benefit Corporation Legislation|url=http://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/29332-Maryland-First-State-in-Union-to-Pass-Benefit-Corporation-Legislation|publisher=]|date=14 April 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The chartering of Benefit Corporations is an attempt to reclaim the original purpose for which corporations were chartered in early America. Then, states chartered corporations to achieve a specific public purpose, such as building bridges or roads. Their legitimacy stemmed from their delegated charter, although they could still earn profits while fulfilling it. | |||

| Over time, however, corporations came to be chartered without any public purpose, while being legally bound to the singular purpose of profit-maximization for its shareholders. Advocates of Benefit Corporations assert that this singular focus has resulted in a variety of societal ills, including the thwarting of democracy, diminished social good, and negative environmental impacts.<ref name=raskin>Raskin, Jamie. "The Rise of Benefit Corporations", ''The Nation'', 2011 June 8. Available at http://www.thenation.com/article/161261/rise-benefit-corporations</ref> | |||

| In April 2010, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass Benefit Corporation legislation. Hawaii, Virginia, California, Vermont, and New Jersey soon followed. Additionally, as of November 2011, Benefit Corporation legislation had been introduced or partially passed in Colorado, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.<ref>B Corp Legislation. Available at http://www.bcorporation.net/publicpolicy. Also see {{cite news|url=http://www.bizjournals.com/baltimore/stories/2010/10/04/daily18.html|title=Md. 'becoming the Delaware of benefit corporations'|publisher=]|date=5 October 2010}}, {{cite web|url=http://www.care2.com/causes/new-jersey-b-corporation-bill-passes-legislature-heads-to-governor-for-signature.html|title=New Jersey B Corporation Bill Passes Legislature; Heads to Governor for Signature|publisher=Care2|date=13 January 2011}}, {{cite web|url=http://www.buffalorising.com/2011/06/new-york-state-senate-and-assembly-pass-benefit-corporation-legislation.html|title=New York State Senate and Assembly Pass Benefit Corporation Legislation|publisher=Buffalo Rising|date=28 June 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Benefit Corporation laws address concerns held by entrepreneurs who wish to raise growth capital but fear losing control of the social or environmental mission of their business. In addition, the laws provide companies the ability to consider factors other than the highest purchase offer at the time of sale, in spite of the ruling on ]. Chartering as a Benefit Corporation also allows companies to distinguish themselves as businesses with a social conscience, and as one that aspires to a standard they consider higher than mere profit-maximization for shareholders.<ref> article by Gar Alperovitz, also appeared in the June 13, 2011 edition of '']''</ref> | |||

| ===Mutual benefit corporations===<!-- ] links to here --> | |||

| A mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a corporation formed in the United States solely for the benefit of its members. An example of a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a golf club. Individuals pay to join the club, memberships may be bought and sold, and any property owned by the club is distributed to its members if the club dissolves. The club can decide, in its corporate bylaws, how many members to have, and who can be a member. Generally, while it is a nonprofit corporation, a mutual benefit corporation is not a charity. Because it is not a charity, a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation cannot obtain 501(c)(3) status. If there is a dispute as to how a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is being operated, it is up to the members to resolve the dispute since the corporation exists to solely serve the needs of its membership and not the general public.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Corporations globally== | ==Corporations globally== | ||

| Line 205: | Line 209: | ||

| Many nations have modeled their own corporate laws on American business law. Corporate law in ], for example, follows the model of New York State corporate law. In addition to typical corporations in the United States, the federal government, in 1971 passed the ] (ANCSA), which authorized the creation of 12 regional native corporations for ] and over 200 village corporations that were entitled to a settlement of land and cash. In addition to the 12 regional corporations, the legislation permitted a 13th regional corporation without a land settlement for those Alaska Natives living out of the ] at the time of passage of ANCSA. | Many nations have modeled their own corporate laws on American business law. Corporate law in ], for example, follows the model of New York State corporate law. In addition to typical corporations in the United States, the federal government, in 1971 passed the ] (ANCSA), which authorized the creation of 12 regional native corporations for ] and over 200 village corporations that were entitled to a settlement of land and cash. In addition to the 12 regional corporations, the legislation permitted a 13th regional corporation without a land settlement for those Alaska Natives living out of the ] at the time of passage of ANCSA. | ||

| ==Corporate taxation== | |||

| {{Main|Corporate tax}} | |||

| In many countries corporate profits are taxed at a corporate tax rate, and dividends paid to shareholders are taxed at a separate rate. Such a system is sometimes referred to as "]", because any profits distributed to shareholders will eventually be taxed twice. One solution to this (as in the case of the Australian and UK tax systems) is for the recipient of the dividend to be entitled to a tax credit which addresses the fact that the profits represented by the dividend have already been taxed. The company profit being passed on is therefore effectively only taxed at the rate of tax paid by the eventual recipient of the dividend. In other systems, dividends are taxed at a lower rate than other income (for example, in the US) or shareholders are taxed directly on the corporation's profits and dividends are not taxed (for example, ]s in the US). | |||

| ==Criticisms== | ==Criticisms== | ||

Revision as of 15:49, 8 August 2012

This article is about business corporations. For other uses, see Corporation (disambiguation). "Corporate" redirects here. For the Bollywood film, see Corporate (film).A corporation is created under the laws of a state as a separate legal entity that has privileges and liabilities that are distinct from those of its members. There are many different forms of corporations. Many corporations are established for business purposes but public bodies, charities and clubs are often corporations as well. Corporations take many forms including: statutory corporations, corporations sole, joint-stock companies and cooperatives. An important (but not universal) contemporary feature of a corporation is limited liability. If a corporation fails, shareholders may lose their investments, and employees may lose their jobs, but neither will be liable for debts to the corporation's creditors.

Despite not being natural persons, corporations are recognized by the law to have rights and responsibilities like natural persons ("people"). Corporations can exercise human rights against real individuals and the state, and they can themselves be responsible for human rights violations. Corporations are conceptually immortal but they can "die" when they are "dissolved" either by statutory operation, order of court, or voluntary action on the part of shareholders. Insolvency may result in a form of corporate 'death', when creditors force the liquidation and dissolution of the corporation under court order, but it most often results in a restructuring of corporate holdings. Corporations can even be convicted of criminal offenses, such as fraud and manslaughter. However corporations are not considered living entities in the way that humans are.

Early corporations were established by charter (i.e. by an ad hoc act granted by a monarch or passed by a parliament or legislature). Most jurisdictions now allow the creation of new corporations through registration. In addition to legal personality, registered companies tend to have limited liability, be owned by shareholders who can transfer their shares to others, and controlled by a board of directors who the shareholders appoint.

Types

- For a list of types of corporation and other business types by country, see Types of business entity.

Depending on the jurisdiction, there are four types of corporations, of which a particular jurisdiction will allow two of them. The types of corporations which a jurisdiction will charter either are for-profit corporations and not-for-profit corporations, or it will charter stock corporations and non-stock corporations. The main difference is that a corporation that is for profit is usually a stock corporation, but can be a non-stock corporation, but a not-for-profit corporation is usually a non-stock corporation. There are certain states which do allow a non-profit corporation to issue stock, including Kansas, Delaware, and Michigan. Generally these states allow the stock for purposes of control of the non-profit corporation but allow no dividends.

Most corporations are registered with the local jurisdiction as either a stock corporation or a non-stock corporation. Stock corporations sell stock to generate capital. A stock corporation must always be a for-profit corporation. A non-stock corporation cannot have stockholders, but may have members who have voting rights in the corporation.

Some jurisdictions (Washington, D.C., for example) separate corporations into for-profit and non-profit, as opposed to dividing into stock and non-stock.

Several states also allow a variation of the corporation for use by professionals (i.e., those individuals typically considered as professionals who require a license from the state to conduct business). In some states, such as Georgia, these corporations are known as "professional corporations". A professional corporation will always be a for-profit corporation.

For-profit and non-profit

Main article: non-profit organizationCorporate entities may be formed for either profit- or not-for-profit (also called non-profit) purposes. Many non-profit corporations are also tax-exempt (such as charities), which means the corporation's income is not taxed under federal or state law or both.

Different principles of corporate governance apply to a wide variety of business and non-profit activities. Although the laws governing these creatures of statute differ between various types of entities, many of the principles and rules that govern profit-making enterprises also apply to non-profit organizations — as the underlying structures of these two types of entity often resemble each other.

Closely held corporations and publicly traded corporations

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The institution most often referenced by the word "corporation" is a publicly traded corporation, the shares of which are traded on a public stock exchange (for example, the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq in the United States) where shares of stock of corporations are bought and sold by and to the general public. Most of the largest businesses in the world are publicly traded corporations. However, the majority of corporations are said to be closely held, privately held or close corporations, meaning that no ready market exists for the trading of shares. Many such corporations are owned and managed by a small group of businesspeople or companies, although the size of such a corporation can be as vast as the largest public corporations.

Closely held corporations do have some advantages over publicly traded corporations. A small, closely held company can often make company-changing decisions much more rapidly than a publicly traded company. A publicly traded company is also at the mercy of the market, having capital flow in and out based not only on what the company is doing but also on what the market and even what the competitors are doing. Publicly traded companies also have advantages over their closely held counterparts. Publicly traded companies often have more working capital and can delegate debt throughout all shareholders. This means that people invested in a publicly traded company will each take a much smaller hit to their own capital as opposed to those involved with a closely held corporation. Publicly traded companies though suffer from this exact advantage. A closely held corporation can often voluntarily take a hit to profit with little to no repercussions (as long as it is not a sustained loss). A publicly traded company though often comes under extreme scrutiny if profit and growth are not evident to stock holders, thus stock holders may sell, further damaging the company. Often this blow is enough to make a small public company fail.

Often communities benefit from a closely held company more so than from a public company. A closely held company is far more likely to stay in a single place that has treated them well, even if going through hard times. The shareholders can incur some of the damage the company may receive from a bad year or slow period in the company profits. Closely held companies often have a better relationship with workers. In larger, publicly traded companies, often when a year has gone badly the first area to feel the effects are the work force with lay offs or worker hours, wages or benefits being cut. Again, in a closely held business the shareholders can incur this profit damage rather than passing it to the workers.

The affairs of publicly traded and closely held corporations are similar in many respects. The main difference in most countries is that publicly traded corporations have the burden of complying with additional securities laws, which (especially in the U.S.) may require additional periodic disclosure (with more stringent requirements), stricter corporate governance standards, and additional procedural obligations in connection with major corporate transactions (for example, mergers) or events (for example, elections of directors).

A closely held corporation may be a subsidiary of another corporation (its parent company), which may itself be either a closely held or a public corporation. In some jurisdictions, the subsidiary of a listed public corporation is also defined as a public corporation (for example, Australia).

Benefit corporation

Main article: Benefit corporationA benefit corporation, or in short-hand a B corporation, is a class of corporation required by law to create general benefit for society as well as for shareholders. Benefit Corporations must create a material positive impact on society, and consider how their decisions affect their employees, community, and the environment. Moreover, they must publicly report on their social and environmental performances using established third-party standards.

The chartering of Benefit Corporations is an attempt to reclaim the original purpose for which corporations were chartered in early America. Then, states chartered corporations to achieve a specific public purpose, such as building bridges or roads. Their legitimacy stemmed from their delegated charter, although they could still earn profits while fulfilling it.

Over time, however, corporations came to be chartered without any public purpose, while being legally bound to the singular purpose of profit-maximization for its shareholders. Advocates of Benefit Corporations assert that this singular focus has resulted in a variety of societal ills, including the thwarting of democracy, diminished social good, and negative environmental impacts.

In April 2010, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass Benefit Corporation legislation. Hawaii, Virginia, California, Vermont, and New Jersey soon followed. Additionally, as of November 2011, Benefit Corporation legislation had been introduced or partially passed in Colorado, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

Benefit Corporation laws address concerns held by entrepreneurs who wish to raise growth capital but fear losing control of the social or environmental mission of their business. In addition, the laws provide companies the ability to consider factors other than the highest purchase offer at the time of sale, in spite of the ruling on Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc.. Chartering as a Benefit Corporation also allows companies to distinguish themselves as businesses with a social conscience, and as one that aspires to a standard they consider higher than mere profit-maximization for shareholders.

Mutual benefit corporations

A mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a corporation formed in the United States solely for the benefit of its members. An example of a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is a golf club. Individuals pay to join the club, memberships may be bought and sold, and any property owned by the club is distributed to its members if the club dissolves. The club can decide, in its corporate bylaws, how many members to have, and who can be a member. Generally, while it is a nonprofit corporation, a mutual benefit corporation is not a charity. Because it is not a charity, a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation cannot obtain 501(c)(3) status. If there is a dispute as to how a mutual benefit nonprofit corporation is being operated, it is up to the members to resolve the dispute since the corporation exists to solely serve the needs of its membership and not the general public.

Corporate law

Main article: Corporate law| This article is part of a series on | ||||||||

| Corporate law | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| By jurisdiction | ||||||||

| General corporate forms | ||||||||

|

Corporate forms by jurisdiction

|

||||||||

| Doctrines | ||||||||

| Related areas | ||||||||

The existence of a corporation requires a special legal framework and body of law that specifically grants the corporation legal personality, and typically views a corporation as a fictional person, a legal person, or a moral person (as opposed to a natural person). Corporate statutes typically empower corporations to own property, sign binding contracts, and pay taxes in a capacity separate from that of its shareholders (who are sometimes referred to as "members"). According to Lord Chancellor Haldane,

...a corporation is an abstraction. It has no mind of its own any more than it has a body of its own; its active and directing will must consequently be sought in the person of somebody who is really the directing mind and will of the corporation, the very ego and centre of the personality of the corporation.

— Lennard's Carrying Co Ltd v Asiatic Petroleum Co Ltd AC 705

The legal personality has two economic implications. First it grants creditors (as opposed to shareholders or employees) priority over the corporate assets upon liquidation. Second, corporate assets cannot be withdrawn by its shareholders, nor can the assets of the firm be taken by personal creditors of its shareholders. The second feature requires special legislation and a special legal framework, as it cannot be reproduced via standard contract law.

The regulations most favorable to incorporation include:

| Regulation | Description |

|---|---|

| Limited liability | Unlike a partnership or sole proprietorship, shareholders of a modern business corporation have "limited" liability for the corporation's debts and obligations. As a result, their losses cannot exceed the amount which they contributed to the corporation as dues or payment for shares. This enables corporations to "socialize their costs" for the primary benefit of shareholders; to socialize a cost is to spread it to society in general. The economic rationale for this is that it allows anonymous trading in the shares of the corporation, by eliminating the corporation's creditors as a stakeholder in such a transaction. Without limited liability, a creditor would probably not allow any share to be sold to a buyer at least as creditworthy as the seller. Limited liability further allows corporations to raise large amounts of finance for their enterprises by combining funds from many owners of stock. Limited liability reduces the amount that a shareholder can lose in a company. This increases the attraction to potential shareholders, and thus increases both the number of willing shareholders and the amount they are likely to invest. However, some jurisdictions also permit another type of corporation, in which shareholders' liability is unlimited, for example the unlimited liability corporation in two provinces of Canada, and the unlimited company in the United Kingdom. |

| Perpetual lifetime | Another advantage is that the assets and structure of the corporation may continue beyond the lifetimes of its shareholders and bondholders. This allows stability and the accumulation of capital, which is thus available for investment in larger and longer-lasting projects than if the corporate assets were subject to dissolution and distribution. This was also important in medieval times, when land donated to the Church (a corporation) would not generate the feudal fees that a lord could claim upon a landholder's death. In this regard, see Statute of Mortmain. (However a corporation can be dissolved by a government authority, putting an end to its existence as a legal entity. But this usually only happens if the company breaks the law, for example, fails to meet annual filing requirements, or in certain circumstances if the company requests dissolution.) |

Ownership and control

A corporation is typically owned and controlled by its members. In a joint-stock company the members are known as shareholders and their share in the ownership, control and profits of the corporation is determined by the portion of shares in the company that they own. Thus a person who owns a quarter of the shares of a joint-stock company owns a quarter of the company, is entitled to a quarter of the profit (or at least a quarter of the profit given to shareholders as dividends) and has a quarter of the votes capable of being cast at general meetings.

In another kind of corporation the legal document which established the corporation or which contains its current rules will determine who the corporation's members are. Who is a member depends on what kind of corporation is involved. In a worker cooperative the members are people who work for the cooperative. In a credit union the members are people who have accounts with the credit union.

The day-to-day activities of a corporation is typically controlled by individuals appointed by the members. In some cases this will be a single individual but more commonly corporations are controlled by a committee or by committees. Broadly speaking there are two kinds of committee structure.

- A single committee known as a board of directors is the method favored in most common law countries. Under this model the board of directors is composed of both executive and non-executive directors. The latter being meant to supervise the formers' management of the company

- A two-tiered committee structure with a supervisory board and a managing board is common in civil law countries. Under this model the executive directors sit on one committee while the non-executive directors sit on the other.

Formation

Historically, corporations were created by a charter granted by government. Today, corporations are usually registered with the state, province, or national government and regulated by the laws enacted by that government. Registration is the main prerequisite to the corporation's assumption of limited liability. The law sometimes requires the corporation to designate its principal address, as well as a registered agent (a person or company designated to receive legal service of process). It may also be required to designate an agent or other legal representative of the corporation.

Generally, a corporation files articles of incorporation with the government, laying out the general nature of the corporation, the amount of stock it is authorized to issue, and the names and addresses of directors. Once the articles are approved, the corporation's directors meet to create bylaws that govern the internal functions of the corporation, such as meeting procedures and officer positions.

The law of the jurisdiction in which a corporation operates will regulate most of its internal activities, as well as its finances. If a corporation operates outside its home state, it is often required to register with other governments as a foreign corporation, and is almost always subject to laws of its host state pertaining to employment, crimes, contracts, civil actions, and the like.

Naming

Corporations generally have a distinct name. Historically, some corporations were named after their membership: for instance, "The President and Fellows of Harvard College." Nowadays, corporations in most jurisdictions have a distinct name that does not need to make reference to their membership. In Canada, this possibility is taken to its logical extreme: many smaller Canadian corporations have no names at all, merely numbers based on a registration number (for example, "12345678 Ontario Limited"), which is assigned by the provincial or territorial government where the corporation incorporates.

In most countries, corporate names include a term or an abbreviation that denotes the corporate status of the entity (for example, "Incorporated" or "Inc." in the United States) or the limited liability of its members (for example, "Limited" or "Ltd."). These terms vary by jurisdiction and language. In some jurisdictions they are mandatory, and in others they are not. Their use puts everybody on constructive notice that they are dealing with an entity whose liability is limited, and does not reach back to the persons who own the entity: one can only collect from whatever assets the entity still controls when one obtains a judgment against it.

Some jurisdictions do not allow the use of the word "company" alone to denote corporate status, since the word "company" may refer to a partnership or some other form of collective ownership (in the United States it can be used by a sole proprietorship but this is not generally the case elsewhere).

Financial disclosure

In many jurisdictions, corporations whose shareholders benefit from limited liability are required to publish annual financial statements and other data, so that creditors who do business with the corporation are able to assess the creditworthiness of the corporation and cannot enforce claims against shareholders. Shareholders therefore experience some loss of privacy in return for limited liability. This requirement generally applies in Europe, but not in Anglo-American jurisdictions, except for publicly traded corporations, where financial disclosure is required for investor protection.

Unresolved issues

The nature of the corporation continues to evolve in response to new situations as existing corporations promote new ideas and structures, the courts respond, and governments issue new regulations. A question of long standing is that of diffused responsibility. For example, if a corporation is found liable for a death, how should culpability and punishment for it be allocated among shareholders, directors, management and staff, and the corporation itself? See corporate liability, and specifically, corporate manslaughter.

The law differs among jurisdictions, and is in a state of flux. Some argue that shareholders should be ultimately responsible in such circumstances, forcing them to consider issues other than profit when investing, but a corporation may have millions of small shareholders who know nothing about its business activities. Moreover, traders — especially hedge funds — may turn over shares in corporations many times a day. The issue of corporate repeat offenders (see H. Glasbeek, "Wealth by Stealth: Corporate Crime, Corporate Law, and the Perversion of Democracy", ISBN 978-1-896357-41-6, Between the Lines Press: Toronto 2002) raises the question of the so-called "death penalty for corporations."

History

Main articles: History of corporations and List of oldest companies

The word "corporation" derives from corpus, the Latin word for body, or a "body of people." By the time of Justinian (reigned 527-565), Roman Law recognized a range of corporate entities under the names universitas, corpus or collegium. These included the state itself (the populus Romanus), municipalities, and such private associations as sponsors of a religious cult, burial clubs, political groups, and guilds of craftsmen or traders. Such bodies commonly had the right to own property and make contracts, to receive gifts and legacies, to sue and be sued, and, in general, to perform legal acts through representatives. Private associations were granted designated privileges and liberties by the emperor. Entities which carried on business and were the subjects of legal rights were found in ancient Rome, and the Maurya Empire in ancient India. In medieval Europe, churches became incorporated, as did local governments, such as the Pope and the City of London Corporation. The point was that the incorporation would survive longer than the lives of any particular member, existing in perpetuity. The alleged oldest commercial corporation in the world, the Stora Kopparberg mining community in Falun, Sweden, obtained a charter from King Magnus Eriksson in 1347. Many European nations chartered corporations to lead colonial ventures, such as the Dutch East India Company or the Hudson's Bay Company, and these corporations came to play a large part in the history of corporate colonialism.

During the time of colonial expansion in the 17th century, the true progenitors of the modern corporation emerged as the "chartered company". Acting under a charter sanctioned by the Dutch government, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) defeated Portuguese forces and established itself in the Moluccan Islands in order to profit from the European demand for spices. Investors in the VOC were issued paper certificates as proof of share ownership, and were able to trade their shares on the original Amsterdam stock exchange. Shareholders are also explicitly granted limited liability in the company's royal charter. In the late 18th century, Stewart Kyd, the author of the first treatise on corporate law in English, defined a corporation as,

a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having perpetual succession under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual, particularly of taking and granting property, of contracting obligations, and of suing and being sued, of enjoying privileges and immunities in common, and of exercising a variety of political rights, more or less extensive, according to the design of its institution, or the powers conferred upon it, either at the time of its creation, or at any subsequent period of its existence.

— A Treatise on the Law of Corporations, Stewart Kyd (1793-1794)

Mercantilism

See also: Mercantilism and South Sea Bubble

Labeled by both contemporaries and historians as "the grandest society of merchants in the universe", the British East India Company would come to symbolize the dazzlingly rich potential of the corporation, as well as new methods of business that could be both brutal and exploitative. On 31 December 1600, the English monarchy granted the company a 15-year monopoly on trade to and from the East Indies and Africa. By 1611, shareholders in the East India Company were earning an almost 150% return on their investment. Subsequent stock offerings demonstrated just how lucrative the Company had become. Its first stock offering in 1613-1616 raised £418,000, and its first offering in 1617-1622 raised £1.6 million.

In the United States, government chartering began to fall out of vogue in the mid-19th century. Corporate law at the time was focused on protection of the public interest, and not on the interests of corporate shareholders. Corporate charters were closely regulated by the states. Forming a corporation usually required an act of legislature. Investors generally had to be given an equal say in corporate governance, and corporations were required to comply with the purposes expressed in their charters. Many private firms in the 19th century avoided the corporate model for these reasons (Andrew Carnegie formed his steel operation as a limited partnership, and John D. Rockefeller set up Standard Oil as a trust). Eventually, state governments began to realize the greater corporate registration revenues available by providing more permissive corporate laws. New Jersey was the first state to adopt an "enabling" corporate law, with the goal of attracting more business to the state. Delaware followed, and soon became known as the most corporation-friendly state in the country after New Jersey raised taxes on the corporations, driving them out. New Jersey reduced these taxes after this mistake was realized, but by then it was too late; even today, most major public corporations in the United States are set up under Delaware law.

By the beginning of the 19th century, government policy on both sides of the Atlantic began to change, reflecting the growing popularity of the proposition that corporations were riding the economic wave of the future. In 1819, the U. S. Supreme Court granted corporations a plethora of rights they had not previously recognized or enjoyed. Corporate charters were deemed "inviolable", and not subject to arbitrary amendment or abolition by state governments. The Corporation as a whole was labeled an "artificial person", possessing both individuality and immortality.

At around the same time, British legislation was similarly freeing the corporation from historical restrictions. In 1844 the British Parliament passed the Joint Stock Companies Act, which allowed companies to incorporate without a royal charter or an Act of Parliament. Ten years later, limited liability, the key provision of modern corporate law, passed into English law: in response to increasing pressure from newly emerging capital interests, Parliament passed the Limited Liability Act 1855, which established the principle that any corporation could enjoy limited legal liability on both contract and tort claims simply by registering as a "limited" company with the appropriate government agency.

This prompted the English periodical The Economist to write in 1855 that "never, perhaps, was a change so vehemently and generally demanded, of which the importance was so much overrated. " The glaring inaccuracy of the second part of this judgment was recognized by the same magazine more than 70 years later, when it claimed that, "he economic historian of the future. . . may be inclined to assign to the nameless inventor of the principle of limited liability, as applied to trading corporations, a place of honour with Watt and Stephenson, and other pioneers of the Industrial Revolution. "

Modern corporations

By the end of the 19th century the Sherman Act, New Jersey allowing holding companies, and mergers resulted in larger corporations with dispersed shareholders. (See The Modern Corporation and Private Property The well-known Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad decision began to influence policymaking and the modern corporate era had begun.

The 20th century saw a proliferation of enabling law across the world, which helped to drive economic booms in many countries before and after World War I. Starting in the 1980s, many countries with large state-owned corporations moved toward privatization, the selling of publicly owned services and enterprises to corporations. Deregulation (reducing the regulation of corporate activity) often accompanied privatization as part of a laissez-faire policy. Another major postwar shift was toward the development of conglomerates, in which large corporations purchased smaller corporations to expand their industrial base. Japanese firms developed a horizontal conglomeration model, the keiretsu, which was later duplicated in other countries as well.

Corporate taxation

Main article: Corporate taxIn many countries corporate profits are taxed at a corporate tax rate, and dividends paid to shareholders are taxed at a separate rate. Such a system is sometimes referred to as "double taxation", because any profits distributed to shareholders will eventually be taxed twice. One solution to this (as in the case of the Australian and UK tax systems) is for the recipient of the dividend to be entitled to a tax credit which addresses the fact that the profits represented by the dividend have already been taxed. The company profit being passed on is therefore effectively only taxed at the rate of tax paid by the eventual recipient of the dividend. In other systems, dividends are taxed at a lower rate than other income (for example, in the US) or shareholders are taxed directly on the corporation's profits and dividends are not taxed (for example, S corporations in the US).

Corporations globally