| Revision as of 08:10, 28 December 2012 edit202.215.106.50 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:04, 30 December 2012 edit undo182.182.44.244 (talk) →Mughal EmpireNext edit → | ||

| Line 1,558: | Line 1,558: | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| The ] was an ]-] imperial power from ], that ruled most of the ] in 16th and 17th century.<ref></ref> In 1526, ], a ] descendant of ] and ] from ] in Uzbekistan, swept across the ] and established the ], which lasted for over 200 years.<ref></ref> The ] ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600; it went into a slow decline after 1707 and was finally defeated during the ] also called the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The famous emperor ], who was the grandson of ], tried to establish an inclusive empire |

The ] was an ]-] imperial power from ], that ruled most of the ] in 16th and 17th century.<ref></ref> In 1526, ], a ] descendant of ] and ] from ] in Uzbekistan, swept across the ] and established the ], which lasted for over 200 years.<ref></ref> The ] ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600; it went into a slow decline after 1707 and was finally defeated during the ] also called the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The famous emperor ], who was the grandson of ], tried to establish an inclusive empire. | ||

| Aurangzeb was a notable expansionist and was also among the most wealthy of the previous Mughal rulers with an annual yearly tribute of £38,624,680 (in the year 1690), during his lifetime victories in the south expanded the ] to more than 1.25 million square miles, he ruled over more than 150 million subjects, constituting nearly one fourth of the world's population<ref>name:Richards1993</ref><ref>http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/ikram/graphics/india1700.jpg</ref>. Aurangzeb is also considered as one of the most powerful rulers of the age, due his vast imperial entourage of over 500,000 followers<ref> Wolpert, Stanley (2003). New History of India (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195166779.</ref> and his massive ] consisted of nearly 1 million servicemen. | |||

| ===== Early Ottoman Empire ===== | ===== Early Ottoman Empire ===== | ||

Revision as of 06:04, 30 December 2012

Historical powers include great powers, nations, or empires in history.

The term "Great power" represent the most important world powers. In a modern context, recognised great powers came about first in Europe during the post-Napoleonic era. The formalization of the division between small powers and great powers came about with the signing of the Treaty of Chaumont in 1814. A "great power" is a nation or state that, through its great economic, political and military strength, is able to exert power and influence over not only its own region of the world, but beyond to others.

The historical term "Great Nation", distinguished aggregate of people inhabiting a particular country or territory, and "Great Empire", considerable group of states or countries under a single supreme authority, are colloquial; use is seen in ordinary historical conversations (historical jargon).

History

Ancient powers

- 3000 BC – 476 AD

Ancient Near East

Main article: Ancient Near East| Ancient Near East | ||

|---|---|---|

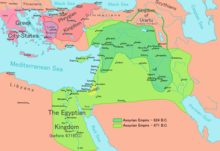

Lighter areas show direct control, darker areas represent spheres of influence. |

The term ancient Near East encompasses the early civilizations during the time roughly spanning the Bronze Age from the rise of Sumer and Gerzeh in the 4th millennium BCE to the expansion of the Persian Empire in the 6th century BCE. The ancient Near East is generally understood as encompassing Mesopotamia (modern Iraq and Syria), Persia (modern Iran), Armenia, the Levant (modern Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestinian Authority), and at times Anatolia (modern Turkey) and Ancient Egypt.

Sumer and Akkad

Main articles: Sumer and Akkadian EmpireSumer (or Šumer) was one of the early civilizations of the Ancient Near East, located in the southern part of Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) from the time of the earliest records in the mid 4th millennium BC until the rise of Babylonia in the late 3rd millennium BC. The term "Sumerian" applies to all speakers of the Sumerian language. Sumer (together with Ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley Civilization) is considered the first settled society in the world to have manifested all the features needed to qualify fully as a "civilization", eventually expanding into the first empire in history, the Akkadian Empire.

The profound political, social, and cultural influence imposed upon the Near East by the civilization known as the Ancient Babylonian Empire was the most pervasive in this historical period. The city itself - Babylon - positioned itself as a center of pivotal historical developments for centuries. There were 3 major Babylonian Dynasties: Amorite, Kassite, and Chaldean. This political entity was most predominate within the southern portion of Mesopotamia. It existed as an unremitting rival of the northern Assyrian Mesopotamians. Although it was assaulted and militarily overcome on several occasions,it did exist as a stalwart presence from the latter 3rd millennium BCE to the middle of the 6th century BCE, when it expanded its borders under the auspices of the rather famous Nebuchadnezzar the Great, and thereby overcame the Assyrians swiftly, and established and maintained strongholds throughout the Near Eastern region with a centralized administrative methodology and unyielding system of control. This period would be considered the apex of the Babylonian City-State's dominance in its two-and-a-half millennium history. Ancient Babylon was officially conquered by the Achemidian Persian Empire in the late 6th century BCE.

Elam

Main article: Elam| Elamite Empire |

|---|

The approximate Bronze Age Elamite Empire extension of the Persian Gulf is shown. |

Elam was situated just to the east of Mesopotamia and was one of the oldest recorded civilizations. Elam was centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of Khuzestan and Ilam Province (which takes its name from Elam), as well as a small part of southern Iraq. In the Old Elamite period (Middle Bronze Age), Elam consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centered in Anshan, and from the mid-2nd millennium BC, it was centered in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands.

Elam was part of the early cities of the Ancient Near East during the Chalcolithic (Copper Age). The emergence of written records from around 3000 BC also parallels Mesopotamian history where writing was used slightly earlier. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally, this was done through a federated governmental structure.

Elamite culture played a crucial role in the Gutian Empire (Persian Empire) especially during the Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded it, when the Elamite language remained among those in official use. The Elamite language is generally treated as an isolate language. As such, the Elamite period is considered a starting point for the history of Iran.

Hurrian kingdoms

Main article: Hurrians| Hurrians |

|---|

Akkad Elam |

The Hurrians refer to a people who inhabited northern Mesopotamia beginning approximately 2500 BC. The Hurrian kingdoms of the Ancient Near East was in Northern Mesopotamia and its people lived in the adjacent regions during the Bronze Age. The largest and most influential Hurrian nation was the kingdom of Mitanni. The population of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia to a large part consisted of Hurrians, and there is significant Hurrian influence in Hittite mythology.

By the Early Iron Age, the Hurrians had been assimilated with other peoples, except perhaps in the kingdom of Urartu. The Hurrian peoples were not incredibly united, existing as quasi-feudal kingdoms. The kingdom of Mitanni was at its height towards the close of the 14th century BC. By the 13th century BC, the Hurrian kingdoms had been conquered by foreign powers, chiefly the Assyrians.

Assyria

Main article: Assyria| Neo-Assyrian Empire |

|---|

Neo-Assyrian Empire Assyrian Empire - 824 BC Assyrian Empire - 671 BC Other Judah Phrygian Kingdom Lydian Kingdom Greek City States |

In the earliest historical times, the term Assyria referred to a region on the Upper Tigris river, named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur. Later, as a nation and empire that came to control all of the Fertile Crescent, Egypt and much of Anatolia, the term "Assyria proper" referred to roughly the northern half of Mesopotamia (the southern half being Babylonia), with Nineveh as its capital. The Assyrian homeland was located near a mountainous region, extending along the Tigris as far as the high Gordiaean or Carduchian mountain range of Armenia, sometimes known as the "Mountains of Ashur". The Assyrian kings controlled a large kingdom at three different times in history. These are called the Old, Middle, and Neo-Assyrian kingdoms, or periods. The most powerful and best-known nation of these periods is the Neo-Assyrian Empire, 934-609 BC.

Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) attacked and reduced Babylonia to vassalage, and defeated Aramea, Israel, Urartu, Phoenicia and the neo Hittite states, forcing all of these to pay tribute to Assyria. Shamshi-Adad V (822-811 BC) inherited an empire beset by civil war which he took most of his reign to quell. He was succeeded by Adad-nirari III who was merely a boy. The Empire was thus ruled by the famed queen Semiramis until 806 BC. In that year Adad-nirari III took the reins of power. After his premature death, Assyria failed to expand further during the reigns of Shalmaneser IV (782-773 BC), Ashur-dan III (772-755 BC) and Ashur-nirari V (754-746 BC).

Under Ashurbanipal (669-627 BC) its domination spanned from the Caucasus Mountains in the north to Nubia, Egypt and Arabia in the south, and from Cyprus and Antioch in the west to Persia in the east. Ashurbanipal destroyed Elam and smashed a rebellion led by his own brother Shamash-shum-ukim who was the Assyrian king of Babylon, exacting savage revenge on the Chaldeans, Nabateans, Arabs and Elamites who had supported him. Persia and Media were regarded as vassals of Ashurbanipal. He built vast libraries and initiated a surge in the building of temples and palaces.

Hittite Empire

Main article: Hittite Empire| Hittite Empire |

|---|

Hittite region Hittite core region Egyptian region Outlying regions |

The Hittites were an ancient people who spoke an Indo-European language, and established a kingdom centered at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia from the 18th century BC. In the 14th century BC, the Hittite empire was at its height, encompassing central Anatolia, north-western Syria as far as Ugarit, and upper Mesopotamia. After 1180 BC, the empire disintegrated into several independent "Neo-Hittite" city-states, some surviving until as late as the 8th century BC.

The Hittites were also famous for their skill in building and using chariots, as the Battle of Kadesh demonstrates. The Hittites were pioneers of the Iron Age, manufacturing iron artifacts from as early as the 14th century BC, making them possibly even the first to do so. The Hittites passed much knowledge and lore from the Ancient Near East to the newly arrived Greeks in Europe.

Hittite prosperity was mostly dependent on control of the trade routes and metal sources. Because of the importance of Northern Syria to the vital routes linking the Cilician gates with Mesopotamia, defense of this area was crucial, and was soon put to the test by Egyptian expansion under Pharaoh Rameses II. The outcome of the Battle of Kadesh is uncertain, though it seems that the timely arrival of Egyptian reinforcements prevented total Hittite victory. The Egyptians forced the Hittites to take refuge in the fortress of Kadesh, but their own losses prevented them from sustaining a siege. This battle took place in the 5th year of Rameses (c.1274 BC by the most commonly used chronology).

Median Empire

- 625-550 BC

| Median Empire |

|---|

Median imperial regions Outlying regions |

The Median Empire was the first empire on the territory of Persia. By the 6th century BC, after having together with the Babylonians defeated the Neo-Assyrian Empire. In Greek references to "Median" people there is no clear distinction between the "Persians" and the "Medians"; in fact for a Greek to become "too closely associated with Iranian culture" was "to become medianized, not persianized". The Median kingdom was a short-lived Iranian state and the textual and archaeological sources of that period are rare and little could be known from the Median culture which nevertheless made a "profound, and lasting, contribution to the greater world of Iranian culture". The Medes were able to establish their own empire, the largest of its day, lasting for about sixty years, from the sack of Nineveh in 612 BC until 549 BC when Cyrus the Great established the Achaemenid Empire by defeating his overlord and grandfather, Astyages, king of Media.

Achaemenid Empire

- 559 BC–330 BC

| Achaemenid Empire |

|---|

Outlying regions Achaemenid imperial region cities, battles, power centers |

The Achaemenid Empire was the first of the Persian Empires to rule over significant portions of Greater Iran. At the height of its power, the Empire spanned over three continents and was the most powerful empire of his time. It also eventually incorporated the following territories: in the east modern Afghanistan and beyond into central Asia, and parts of Pakistan; in the north and west all of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), the upper Balkans peninsula (Thrace), and most of the Black Sea coastal regions; in the west and southwest the territories of modern Iraq, northern Saudi-Arabia, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, all significant population centers of ancient Egypt and as far west as portions of Libya.

Encompassing approximately 7.5 million square kilometers, the Achaemenid Empire was territorially the largest empire of antiquity. In its time it had political power over neighboring countries, and had high cultural and economic achievements during its lengthy rule over a vast region from its picturesque capital at Persepolis.

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BC), followed by Issus (333 BC), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BC). Afterwards, he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrendered in early 330 BC. From Persepolis, Alexander headed north to Pasargadae where he visited the tomb of Cyrus, the burial of the man whom he had heard of from Cyropedia.

Parthian Empire

Main article: Parthian Empire| Parthian Empire |

|---|

Parthian region Outlying Regions |

The Parthian Empire was the third Iranian Empire. At the height of its power, the empire ruled most of Greater Iran, Mesopotamia and Armenia. But unlike most other Iranian monarchies, the Parthian followed a vassalary system, which they adopted from the Seleucids. The Arsacid culture was not a single coherent state, but instead made up of numerous tributary (but otherwise independent) kingdoms.

The Parthians largely adopted the art, architecture, religious beliefs, and royal insignia of their culturally heterogeneous empire, which encompassed Persian, Hellenistic, and regional cultures. For about the first half of its existence, the Arsacid court adopted elements of Greek culture, though it eventually saw a gradual revival of Iranian traditions. The Arsacid rulers were titled the 'King of Kings', as a claim to be the heirs to the Achaemenid Empire; indeed, they accepted many local kings as vassals where the Achaemenids would have had centrally appointed, albeit largely autonomous, satraps. The court did appoint a small number of satraps, largely outside Iran, but these satrapies were smaller and less powerful than the Achaemenid potentates. With the expansion of Arsacid power, the seat of central government shifted from Nisa, Turkmenistan to Ctesiphon along the Tigris (south of modern Baghdad, Iraq), although several other sites also served as capitals.

Sassanid Empire

Main article: Sassanid Empire| Sassanid Empire |

|---|

Sassanid regions Outlying Regions |

The Sassanid Empire is the name used for the fourth Iranian dynasty, and the second Persian Empire (226 - 651). The empire's territory encompassed all of today's Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Afghanistan, eastern parts of Turkey, and parts of Syria, Pakistan, Caucasia, Central Asia and Arabia. During Khosrau II's rule in 590–628 Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon were also briefly annexed to the Empire. The Sassanid era, encompassing the length of the Late Antiquity period, is considered to be one of the most important and influential historical periods in Iran. In many ways the Sassanid period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization.

The empire constituted the last great Iranian Empire before the Muslim conquest and adoption of Islam. The Sassanids never mounted a truly effective resistance to the pressure applied by the initial Arab armies. Ctesiphon fell after a prolonged siege. Yazdegerd fled eastward from Ctesiphon, leaving behind him most of the Empire's vast treasury. The Arabs captured Ctesiphon shortly afterward, leaving the Sassanid government strapped for funds and acquiring a powerful financial resource for their own use. A number of Sassanid governors attempted to combine their forces to throw back the invaders, but the effort was crippled by the lack of a strong central authority, and the governors were defeated at the Battle of Nihawānd. The empire, with its military command structure non-existent, its non-noble troop levies decimated, its financial resources effectively destroyed, and the Asawaran knightly caste destroyed piecemeal, was utterly helpless in the face of the invaders. Upon hearing the defeat, Persian nobilities fled further inland to the eastern province of Khorasan.

Ancient Africa

Very few powers emerged in Africa in the early centuries of recorded history, but those that did were quite influential in and outside of their own realms. Ancient Egypt was a power to be contended with by both the Near East, the Mediterranean and Subsahran Africa. Further to the south, the distant but never reclusive Kingdom of Kush gained a reputation for wealth and military vigor throughout the ancient world.

Ancient Egypt

Main article: Ancient Egypt| Ancient Egypt |

|---|

Core Regions Territorial control |

Ancient Egypt was one of the world's first civilizations, with its beginnings in the fertile Nile valley around 3000BC. Ancient Egypt reached the zenith of its power during the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BC) under great pharaohs. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. The combination of a fertile river valley, natural borders that made an invasion unfeasible, and a military able to rise to the challenge when needed, turned Egypt a major power. It was one of the first nations to have a system of writing and large scale construction projects. However, as neighboring civilizations developed militaries capable of crossing Egypt's natural barriers, the Egyptian armies were not always able to repel them and so by 1000 BC Egyptian influence as an independent civilization waned.

The New Kingdom pharaohs established a period of unprecedented prosperity by securing their borders and strengthening diplomatic ties with their neighbors. Military campaigns waged under Tuthmosis I and his grandson Tuthmosis III extended the influence of the pharaohs to the largest empire Egypt had ever seen. Amenhotep IV ascended the throne and instituted a series of radical and chaotic reforms. Changing his name to Akhenaten, he touted the god Aten as the supreme deity, suppressed the worship of other deities, and attacked the power of the priestly establishment. Moving the capital to the new city of Akhetaten, he turned a deaf ear to foreign affairs and absorbed himself in his new religion and artistic style. After his death, the religion of the Aten was quickly abandoned, and the subsequent pharaohs erased all mention of Akhenaten's Egyptian heresy, now known as the Amarna Period.

Ramesses the Great ascended the throne, and went on to build more temples, erect more statues and obelisks, and sire more children than any other pharaoh in history. Ramesses led his army against the Hittites in the Battle of Kadesh and, after fighting to a stalemate, finally agreed to the first recorded peace treaty. Egypt's wealth, however, made it a tempting target for invasion, particularly by the Libyans and the Sea Peoples. Initially, the military was able to repel these invasions, but Egypt eventually lost control of Syria and Palestine. The impact of external threats was exacerbated by internal problems such as corruption, tomb robbery and civil unrest. The high priests at the temple of Amun in Thebes accumulated vast tracts of land and wealth, and their growing power splintered the country during the Third Intermediate Period.

The many achievements of the ancient Egyptians include the quarrying, surveying and construction techniques that facilitated the building of monumental pyramids, temples, and obelisks; a system of mathematics, a practical and effective system of medicine, irrigation systems and agricultural production techniques, the first known ships, Egyptian faience and glass technology, new forms of literature, and the earliest known peace treaty. Egypt left a lasting legacy. Its art and architecture were widely copied, and its antiquities carried off to far corners of the world. Its monumental ruins have inspired the imaginations of travellers and writers for centuries. A new-found respect for antiquities and excavations in the early modern period led to the scientific investigation of Egyptian civilization and a greater appreciation of its cultural legacy, for Egypt and the world.

Kush

Main article: Kingdom of Kush| Kingdom of Kush |

|---|

|

The Kingdom of Kush was the earliest of the Subsaharan states in Africa as well as the first to implement iron weapons. It was heavily influenced by Egyptian colonists, but in 1070 BC it became not only independent of Egypt but a fierce rival. It successfully fought off attempts by Egypt to reconquer it, and it began to extend influence over Upper Egypt. By the end of King Kashta's reign in 752 BC, Thebes was under Kushite control.

A slew of able successors took the rest of Egypt and reigned as the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt stretching Kushite control from central Sudan to modern day Israel. The Kushites did not maintain this empire for long and were beaten back by the Assyrians in 653 BC. However, Kush remained a powerful entity in the region. It continued to meddle in Egyptian affairs and control trade resources originating in Subsaharan Africa. It waged a hard-fought campaign against the Roman Empire (27 BC - 22 BC) under the leadership of Queen Amanirenas, and achieved a more than amicable peace with the young Augustus Caesar. The two states work as allies with Kush lending cavalry support to Rome in its conquest of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The kingdom of Kush maintained its status as a regional power until its conquest by the Axumite Empire in 350.

Further information: Twenty-fifth Dynasty of EgyptAksumite Empire

Main article: Aksumite EmpireThe Aksumite Empire was an important trading nation in northeastern Africa, growing from the proto-Aksumite period ca. 4th century BC to achieve prominence by the 1st century AD. It was a major player in the commerce between the Roman Empire and Ancient India and the Aksumite rulers facilitated trade by minting their own currency. The state established its hegemony over the declining Kingdom of Kush and regularly entered the politics of the kingdoms on the Arabian peninsula, and would eventually extend its rule over the region with the conquest of the Himyarite Kingdom. It was considered by historians as one of the most powerful military powers in the world.

Greek powers

Main article: Ancient Greece

| Ancient Greece |

| Athens · Sparta · Macedonian Empire |

Ancient Greece is the civilization belonging to the period of Greek history lasting from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to 146 BC and the Roman conquest of Greece after the Battle of Corinth. At the center of this time period is Classical Greece, which flourished during the 5th to 4th centuries BC, at first under Athenian leadership successfully repelling the military threat of Persian invasion. The Athenian Golden Age ends with the defeat of Athens at the hands of Sparta in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Hellenistic civilization flourished from Central Asia to the western end of the Mediterranean Sea. Classical Greek culture had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire, which carried a version of it to many parts of the Mediterranean region and Europe, for which reason Classical Greece is generally considered to be the seminal culture which provided the foundation of Western civilization.

Athens, after a tyranny in the second half of the 6th century, founded the world's first democracy as a radical solution to prevent the aristocracy regaining power. A citizens' assembly (the Ecclesia), for the discussion of city policy, had existed since the reforms of Draco; all citizens were permitted to attend after the reforms of Solon, but the poorest citizens could not address the assembly or run for office. With the establishment of the democracy, the assembly became the de jure mechanism of government; all citizens had equal privileges in the assembly. However, non-citizens, such as foreigners living in Athens or slaves, had no political rights at all. After the rise of the democracy in Athens, other city-states founded democracies. However, many retained more traditional forms of government. As so often in other matters, Sparta was a notable exception to the rest of Greece, ruled through the whole period by not one, but two hereditary monarchs. This was a form of diarchy.

Athens

Main article: Ancient Athens| Ancient Athens |

|---|

|

Ancient Athens was inhabited around 3,000 years ago. Athens has one of the longest histories of any city in Europe and in the world. It became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BC. Its cultural achievements during the 5th century BC laid the foundations of western civilization. During the Middle Ages, Athens experienced decline and then a recovery under the Byzantine Empire. Athens was relatively prosperous during the Crusades, benefiting from Italian trade.

Fifth-century Athens refers to the Greek city-state Athens in period of roughly 480 BCE-404 BCE. This was a period of Athenian political hegemony, economic growth and cultural flourishing known as the Golden Age of Athens or Age of Pericles. The period began in 480 BCE when an Athenian-led coalition of city-states, known as the Delian League, defeated the Persians at Salamis. As the fifth century wore on, what started as an alliance of independent city-states gradually became an Athenian empire. Eventually, Athens abandoned the pretense of parity among its allies and relocated the Delian League treasury from Delos to Athens, where it funded the building of the Athenian Acropolis. With its enemies under its feet and its political fortunes guided by legendary statesman and orator Pericles, Athens as a center of literature, philosophy (see Greek philosophy) and the arts (see Greek theatre). Some of the most important figures of Western cultural and intellectual history lived in Athens during this period: the dramatists Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides and Sophocles, the philosophers Aristotle, Plato and Socrates,

Sparta

Main article: Sparta| Lacedaemon |

|---|

|

Sparta was a Dorian Greek military state, originally centered in Laconia. As a city-state devoted to military training, Sparta possessed the most formidable army in the Greek world, and after achieving notable victories over the Athenian and Persian Empires, regarded itself as the natural protector of Greece. Laconia or Lacedaemon (Λακεδαίμων) was the name of the wider city-state centered at the city of Sparta, though the name "Sparta" is now used for both.

Following the victories in the Messenian Wars (631 BC), Sparta's reputation as a land-fighting force was unequaled. In 480 BC a small Spartan unit under King Leonidas made a legendary last stand against a massive, invading Persian army at the Battle of Thermopylae. One year later, Sparta assembled at full strength and led a Greek alliance against the Persians at Plataea. There, a decisive Greek victory put an end to the Greco-Persian War along with Persian ambition of expanding into Europe. Even though this war was won by a pan-Greek army, credit was given to Sparta, who besides being the protagonist at Thermopylae and Plataea, had been the nominal leader of the entire Greek expedition.

In later Classical times, Sparta along with Athens, Thebes and Persia had been the main regional powers fighting for supremacy against each other. As a result of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta, a traditionally continental culture, became a naval power. At the peak of her power she subdued many of the key Greek states and even managed to overpower the powerful Athenian navy. By the end of the 5th century she stood out as a state which had defeated at war both the Persian and Athenian Empires, a period which marks the Spartan Hegemony. Sparta was, above all, a militarist state, and emphasis on military fitness began virtually at birth.

Macedonia

Main article: Macedon| Macedon |

|---|

|

Macedon was the name of an ancient kingdom in the northernmost part of ancient Greece, bordering the kingdom of Epirus on the west and the region of Thrace to the east. For a brief period it became the most powerful state in the world after Alexander the Great conquered most of the known world, including the entire Achaemenid Empire, inaugurating the Hellenistic period of Greek history.

The rise of Macedon, from a small kingdom at the periphery of Classical Greek affairs, to one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world (and beyond), occurred in the space of just 25 years, between 359–336 BC. This ascendancy is largely attributable to the personality and policies of Philip II of Macedon. Philip's military skills and expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness brought him early success. He had however first to re-establish a situation which had been greatly worsened by the defeat against the Illyrians in which King Perdiccas himself had died. The Paionians and the Thracians had sacked and invaded the eastern regions of the country, while the Athenians had landed, at Methoni on the coast, a contingent under a Macedonian pretender called Argeus. Using diplomacy, Philip pushed back Paionians and Thracians promising tributes, and crushed the 3,000 Athenian hoplites (359). Momentarily free from his opponents, he concentrated on strengthening his internal position and, above all, his army. His most important innovation was doubtless the introduction of the phalanx infantry corps, armed with the famous sarissa, an exceedingly long spear, at the time the most important army corps in Macedonia.

Philip's son, Alexander the Great, managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central Greek city-states, but also to the Persian empire, including Egypt and lands as far east as the fringes of India. Alexander's adoption of the styles of government of the conquered territories was accompanied by the spread of Greek culture and learning through his vast empire. Although the empire fractured into multiple Hellenic regimes shortly after his death, his conquests left a lasting legacy, not least in the new Greek-speaking cities founded across Persia's western territories, heralding the Hellenistic period. In the partition of Alexander's empire among the Diadochi, Macedonia fell to the Antipatrid dynasty, which was overthrown by the Antigonid dynasty after only a few years.

Hellenistic Kingdoms

Main article: Hellenistic civilization

| Hellenistic civilization |

| Antigony · Ptolemy · Seleucidae · Attaly |

Alexander had made no special preparations for his succession in his newly founded empire and the Apocrypha of his death state that on his death-bed he willed it to those that performed actions well and powerfully. The result was the wars of the Diadochi between his generals (the Diadochi, or 'Successors'), which lasted for forty years before a more-or-less stable arrangement was established, consisting of four major domains:

- The Antigonid dynasty in Macedon and central Greece;

- The Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt based at Alexandria;

- The Seleucid dynasty in Syria and Mesopotamia based at Antioch;

- The Attalid dynasty in Anatolia based at Pergamum.

A further two kingdoms later emerged, the so-called Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdom. Hellenistic culture thrived in its preservation of the past. The states of the Hellenistic period were deeply fixated with the past and its seemingly lost glories. Athens retained its position as the most prestigious seat of higher education, especially in the domains of philosophy and rhetoric, with considerable libraries. Alexandria was a center of Greek learning and the Library of Alexandria had 700,000 volumes. The city of Pergamon became a major center of book production, possessing a library of some 200,000 volumes, second only to Alexandria's. The island of Rhodes boasted a famous finishing school for politics and diplomacy. Antioch was founded as a metropolis and center of Greek learning which retained its status into the era of Christianity. Seleucia replaced Babylon as the metropolis of the lower Tigris.

Seleucid Empire

Main article: Seleucid Empire| Seleucid Empire |

|---|

|

The Seleucid Empire was a Hellenistic empire, and the eastern remnant of the former Achaemenid Persian Empire following its breakup after Alexander the Great's invasion. The Seleucid Empire was centered in the near East. It was a center of Hellenistic culture which maintained the Greek customs and Greek-speaking Macedonian elite.

Seleucid expansion into Greece was abruptly halted after decisive defeats at the hands of the Roman army. Much of the eastern part of the empire was conquered by the Parthians under Mithridates I of Parthia in the mid-2nd century BC, yet the Seleucid kings continued to rule a rump state from Syria until the invasion by Armenian king Tigranes the Great and their ultimate overthrow by the Roman general Pompey.

Ptolemaic Egypt

Main articles: Ptolemaic Egypt and Ptolemaic dynasty| Ptolemaic empire |

|---|

|

The Ptolemaic dynasty, sometimes also known as the Lagids, was a Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period.

Ptolemy, one of the seven somatophylakes (bodyguards) who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (saviour). The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy.

Ptolemaic Egypt began when Ptolemy I Soter declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt in 305 BC and ended with the death of queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and the Roman conquest in 30 BC. The Ptolemaic Kingdom was a powerful Hellenistic state, extending from southern Syria in the east, to Cyrene to the west, and south to the frontier with Nubia. Alexandria became the capital city and a center of Greek culture and trade. To gain recognition by the native Egyptian populace, they named themselves as the successors to the Pharaohs. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life. Hellenistic culture continued to thrive in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies faced rebellions of native Egyptians often caused by an unwanted regime and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome.

Carthage

Main article: Ancient Carthage| Ancient Carthage |

|---|

|

Carthage was a major power over the Western Mediterranean between 575 BC and 272 BC. Carthage as a major power was originally a Phoenician settlement, and when Tyre fell to the Assyrians, Carthage assumed power over the former settlements of the region. The foundation of Carthaginian power was seafaring trade throughout the Western Mediterranean (following the tracks of the Phoenicians). Some 300 colonies were established in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Iberia, and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya. The Phoenicians controlled Cyprus, Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands, as well as minor possessions in Crete and Sicily; the latter settlements were in perpetual conflict with the Greeks. The Phoenicians managed to control all of Sicily for a limited time. The entire area later came under the leadership and protection of Carthage, which in turn dispatched its own colonists to found new cities or to reinforce those that declined with Tyre and Sidon.

The first colonies were made on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth — along the North African coast and on Sicily, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. The centre of the Phoenician world was Tyre, serving as an economic and political hub. The power of this city waned following numerous sieges and its eventual destruction by Alexander the Great, and the role as leader passed to Sidon, and eventually to Carthage. Each colony paid tribute to either Tyre or Sidon, but neither had actual control of the colonies. This changed with the rise of Carthage, since the Carthaginians appointed their own magistrates to rule the towns and Carthage retained much direct control over the colonies. This policy resulted in a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars. Although Rome was originally a land based military power, its sphere of influence soon collided with Carthage's. Carthage was in a constant state of struggle with the Roman Republic, which led to a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars. After the third and final Punic War, Carthage was destroyed and then occupied by Roman forces. Nearly all of the other Phoenician city-states and former Carthaginian dependencies fell into Roman hands from then on.

Ancient India

Main article: History of IndiaAncient India, which consisted of the Indian subcontinent (the modern-day states of India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh) was unified under many emperors and governments in history. Ancient texts mention India under the legendary emperor Bharata, these regions roughly form the entities of modern day greater India. Several Indian empires were able to expand across southern Asia, and sometimes into parts of the Middle East, Central Asia and Southeast Asia.

Nanda Empire

Main article: Nanda Empire| Nanda Empire |

|---|

|

The Nanda Empire originated from Magadha in Ancient India during the 5th and 4th centuries BC. At its greatest extent, the Nandas ruled much of Northern India. The Nandas are sometimes described as the first empire builders in the recorded history of India. They inherited the large kingdom of Magadha. They built up a vast army.

The Nandas never had the opportunity to see their army up against Alexander the Great, who invaded India at the time of Dhana Nanda, since Alexander had to confine his campaign to the plains of Punjab, for his forces, at the prospect of facing a further foe, mutinied at the Hyphasis River (the modern Beas River) refusing to march any further. The Persian and Greek invasions had important repercussions on Indian civilization.

The political systems of the Persians were to influence future forms of governance on the subcontinent, including the administration of the Mauryan dynasty. In addition, the region of Gandhara, or present-day eastern Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan, became a melting pot of Indian, Persian, Central Asian, and Greek cultures and gave rise to a hybrid culture, Greco-Buddhism, which lasted until the 5th century CE and influenced the artistic development of Mahayana Buddhism.

Maurya Empire

Main article: Maurya Empire| Maurya Empire |

|---|

|

The Mauryan Empire was the first political entity to unite most of the Indian subcontinent and expand into Central Asia and the Middle East. Its soft power further spread into much of Persia and Greece due to its military victories over these regions. Its cultural influence also extended west into Egypt and Syria, and east into Thailand, China and Burma.

The Empire was founded in 322 BC by Chandragupta Maurya. Chandragupta waged a war against the nearby Greek powers and won, forcing the Greeks to surrender large amounts of land. Under the reign of Ashoka the Great, the empire became pacifist and turned to spreading its soft power in the form of Buddhism. It has been estimated that the Maurya Dynasty controlled an unprecedented one-third of the world's entire economy, was home to one-third of the world's population at the time (an estimated 50 million out of 150 million human), contained the world's largest city of the time (Pataliputra, estimated to be larger than Rome under Emperor Trajan).

The Empire was divided into four provinces, which one of the four, look like a giant crescents. with the imperial capital at Pataliputra. From Ashokan edicts, the names of the four provincial capitals are Tosali (in the east), Ujjain in the west, Suvarnagiri (in the south), and Taxila (in the north). The head of the provincial administration was the Kumara (royal prince), who governed the provinces as king's representative. The kumara was assisted by Mahamatyas and council of ministers. This organizational structure was reflected at the imperial level with the Emperor and his Mantriparishad (Council of Ministers).

Historians theorize that the organization of the Empire was in line with the extensive bureaucracy described by Kautilya in the Arthashastra: a sophisticated civil service governed everything from municipal hygiene to international trade. According to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants. A vast espionage system collected intelligence for both internal and external security purposes. Having renounced offensive warfare and expansionism, Ashoka nevertheless continued to maintain this large army, to protect the Empire and instill stability and peace across West and South Asia.

Sunga Empire

Main article: Sunga Empire| Sunga Empire |

|---|

|

The Shunga Empire is a Magadha dynasty that controlled North-central and Eastern India as well as parts of the northwest (now Pakistan) from around 185 to 73 BCE. It was established after the fall of the Indian Maurya Empire. The capital of the Sungas was Pataliputra. Later kings such as Bhagabhadra also held court at Vidisha, modern Besnagar in Eastern Malwa. The Sunga Empire is noted for its numerous wars with both foreign and indigenous powers.

While there is much debate on the religious politics of the Sunga dynasty, it is recognized for a number of contributions. Art, education, philosophy, and other learning flowered during this period. Most notably, Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and Mahabhasya were composed in this period, Panini composed the first Sanskrit grammarian Ashtadayai. It is also noted for its subsequent mention in the Malavikaagnimitra. This work was composed by Kalidasa in the later Gupta period, and romanticized the love of Malavika and King Agnimitra, with a background of court intrigue. Artistry on the subcontinent also progressed with the rise of the Mathura school, which is considered the indigenous counterpart to the more Hellenistic Gandhara school of Afghanistan and Pakistan. During the historical Sunga period (185 to 73 BCE), Buddhist activity also managed to survive somewhat in central India (Madhya Pradesh) as suggested by some architectural expansions that were done at the stupas of Sanchi and Barhut, originally started under Emperor Ashoka. It remains uncertain whether these works were due to the weakness of the control of the Sungas in these areas, or a sign of tolerance on their part.

The last of the Sunga emperor was Devabhuti (83–73 BCE). He was assassinated by his minister (Vasudeva Kanva) and is said to have been overfond of the company of women. The Sunga dynasty was then replaced by the subsequent Kanvas.

Satavahana Empire

Main article: Satavahanas| Satavahanas |

|---|

|

The Sâtavâhana Empire started out as feudatories to the Mauryan Empire but declared independence soon after the death of Ashoka (232 BC). They were the first Indic rulers to issue coins struck with their rulers embossed and are known for their patronage of Buddhism resulting in Buddhist monuments from Ellora to Amaravati.

After becoming independent around 230 BCE, Simuka, the founder of the dynasty, conquered Maharashtra, Malwa and part of Madhya Pradesh. He was succeeded by his brother Kanha (or Krishna) (r. 207–189 BCE), who further extended his kingdom to the west and the south. Sātakarnī I was the sixth ruler of the Satavahana. He is said to have ruled for 56 years. Satakarni defeated the Sunga dynasty of North India by wresting Western Malwa from them, and performed several Vedic sacrifices at huge cost, including the Horse Sacrifice – Ashwamedha yajna. He also was in conflict with the Kalinga ruler Kharavela, who mentions him in the Hathigumpha inscription. According to the Yuga Purana he conquered Kalinga following the death of Kharavela. He extended Satavahana rule over Madhya Pradesh and pushed back the Sakas from Pataliputra (he is thought to be the Yuga Purana's "Shata", an abbreviation of the full name “Shri Sata” that occurs on coins from Ujjain), where he subsequently ruled for 10 years. By this time the dynasty was well established, with its capital at Pratishthānapura (Paithan) in Maharashtra, and its power spreading into all of South India.

The Satavahanas formed a cultural bridge and played a vital role in trade and the transfer of ideas and culture to and from the Gangetic plains to the southern tip of India.

Chola Empire

Main article: Chola Empire| Chola Empire |

|---|

|

The Chola Empire ruled much of India and Southeast Asia. The Tamil dynasty which was one of the longest-ruling dynasties in southern India. The earliest datable references to this Tamil dynasty are in inscriptions from the 3rd century BC left by Asoka, of Maurya Empire; as one of the Three Crowned Kings, the dynasty continued to govern over varying territory until the 13th century AD. By the 9th century, under Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola, the Cholas rose as a notable power in south Asia. The Chola Empire stretched as far as Bengal. At its peak, the empire spanned almost 3,600,000 km (1,400,000 sq mi). Rajaraja Chola conquered all of peninsular South India and parts of the Sri Lanka. Rajendra Chola's navies went even further, occupying coasts from Burma (now Myanmar) to Vietnam, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Sumatra, Java, Malaya in South East Asia and Pegu islands. He defeated Mahipala, the king of the Bengal, and to commemorate his victory he built a new capital and named it Gangaikonda Cholapuram.

The heartland of the Cholas was the fertile valley of the Kaveri River, but they ruled a significantly larger area at the height of their power from the later half of the 9th century till the beginning of the 13th century. The whole country south of the Tungabhadra was united and held as one state for a period of two centuries and more. Under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I, the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in South Asia and South-east Asia. The power of the new empire was proclaimed to the eastern world by the celebrated expedition to the Ganges which Rajendra Chola I undertook and by the overthrow after an unprecedented naval war of the maritime empire of Srivijaya, as well as by the repeated embassies to China.

During the period 1010–1200, the Chola territories stretched from the islands of the Maldives in the south to as far north as the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh. Rajaraja Chola conquered peninsular South India, annexed parts of what is now Sri Lanka and occupied the islands of the Maldives. Rajendra Chola sent a victorious expedition to North India that touched the river Ganges and defeated the Pala ruler of Pataliputra, Mahipala. He also successfully invaded kingdoms of the Malay Archipelago. The Chola dynasty went into decline at the beginning of the 13th century with the rise of the Pandyas, who ultimately caused their downfall.

The Cholas left a lasting legacy. Their patronage of Tamil literature and their zeal in building temples has resulted in some great works of Tamil literature and architecture. The Chola kings were avid builders and envisioned the temples in their kingdoms not only as places of worship but also as centres of economic activity. They pioneered a centralised form of government and established a disciplined bureaucracy.

Gupta Empire

Main article: Gupta Empire See also: Origin of the Gupta dynasty| Gupta Empire |

|---|

|

In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Gupta Empire unified much of India. This period is called the Golden Age of India and was marked by extensive achievements in science, technology, engineering, art, dialectic, literature, logic, mathematics, astronomy, religion and philosophy that crystallized the elements of what is generally known as Hindu culture. Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II were the most notable rulers of the Gupta dynasty.

The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent architectures, sculptures and paintings. The Gupta period produced scholars such as Kalidasa, Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Vishnu Sharma, and Vatsyayana who made great advancements in many academic fields. Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural center and set the region up as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in Burma, Sri Lanka, Malay Archipelago and Indochina.

Ancient China

Main article: History of ChinaQin Dynasty

Main article: Qin Dynasty| Qin Dynasty |

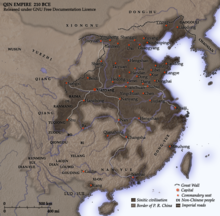

|---|

Qin region Outlying regions |

The Qin Dynasty was preceded by the feudal Zhou Dynasty and followed by the Han Dynasty in China. The unification of China in 221 BCE under the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang marked the beginning of Imperial China, a period which lasted until the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

In 214 BC Qin Shihuang secured his boundaries to the north with a fraction (100,000 men) of his large army, and sent the majority (500,000 men) south to seize still more land. Prior to the events leading to Qin dominance over China, they had gained possession of much of Sichuan to the southwest. The Qin army was unfamiliar with the jungle terrain, and it was defeated by the southern tribes' guerrilla warfare tactics with over 100,000 men lost. However, in the defeat Qin was successful in building a canal to the south, which they used heavily for supplying and reinforcing their troops during their second attack to the south. Building on these gains, the Qin armies conquered the coastal lands surrounding Guangzhou, and took the provinces of Fuzhou and Guilin. They struck as far south as Hanoi. After these victories in the south, Qin Shihuang moved over 100,000 prisoners and exiles to colonize the newly conquered area. In terms of extending the boundaries of his empire, the First Emperor was extremely successful in the south.

Despite its military strength, the Qin Dynasty did not last long. When the first emperor died in 210 BC, his son was placed on the throne by two of the previous emperor's advisers, in an attempt to influence and control the administration of the entire country through him. The advisors squabbled among themselves, however, which resulted in both their deaths and that of the second Qin emperor. Popular revolt broke out a few years later, and the weakened empire soon fell to a Chu lieutenant, who went on to found the Han Dynasty. Despite its rapid end, the Qin Dynasty influenced future Chinese regimes, particularly the Han, and the European name for China is derived from it

See also: Sinae and Romano-Chinese relationsHan Dynasty

Main article: Han Dynasty| Han Dynasty |

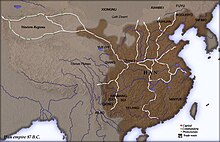

|---|

Han region Outlying regions |

The Han Dynasty (206 BC – AD 220), lasting 400 years, is commonly considered within China to be one of the greatest periods in the entire history of China. At its height, the Han empire extended over a vast territory of 6 million km² and housed a population of approximately 55 million. During this time period, China became a military, economic, and cultural powerhouse. The empire extended its political and cultural influence over Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Vietnam, and Central Asia before it finally collapsed under a combination of domestic and external pressures.

The Han Empire was divided into areas directly controlled by the central government, known as commanderies, and a number of semi-autonomous kingdoms. These kingdoms gradually lost all vestiges of their independence, particularly following the Rebellion of the Seven States. The Xiongnu, a nomadic confederation which dominated the eastern Eurasian Steppe, defeated the Han army in battle in 200 BCE. Following the defeat, a political marriage alliance was negotiated in which the Han became the de facto inferior partner. When, despite the treaty, the Xiongnu continued to raid Han borders, Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) launched several military campaigns against them. The ultimate Han victory in these wars eventually forced the Xiongnu to accept vassal status as Han tributaries. These campaigns expanded Han sovereignty into the Tarim Basin of Central Asia and helped establish the vast trade network known as the Silk Road, which reached as far as the Mediterranean world. Han forces managed to divide the Xiongnu into two competing nations, the Southern and Northern Xiongnu, and forced the Northern Xiongnu across the Ili River. Despite these victories, the territories north of Han's borders were quickly overrun by the nomadic Xianbei Confederation. The Han Dynasty was arguably one of the strongest's empires in the world during the reign of Emperor Wu, though was established as the largest.

Xiongnu

Main article: Xiongnu| Xiongnu |

|---|

Xiongnu Region Outlying regions |

Xiongnu (Hsiung nu) was an empire flourished in the central Asia. Their origin is debatable, but they probably spoke either a Proto Turkic, or a Proto Mongolic or a Yeniseian language. They conquered most of modern Mongolia under their leader Toumen (220-209 BC) in the 3rd century BC. During Modu‘s reign (209-174 BC) they defeated both the Donghu in the east and Yuezhi in the west and they began threatening Han China.

The Great Wall of China had been constructed to protect Chinese towns from the Xiongnu attacks. While the Chinese were trying to bring the Xiongnu under control, something of high significance happened: cross-cultural encounters. A large variety of people (such as traders, ambassadors, hostages, parents in cross-cultural marriages, etc.) served as helpers that passed on ideas, values, and techniques across cultural boundary lines. These encounters helped cultures learn from other cultures. Xiongnu empire disintegrated into two parts during the 1st century, eventually the Xiongnu fell due to the defeat in the Han–Xiongnu War.

See also: SericaRoman Empire

Main article: Roman Empire| Roman Empire |

|---|

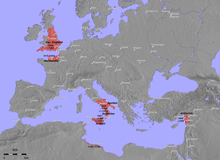

Roman province (Senatorial and Imperial) Outlying Regions |

The Roman Empire is widely known as ancient Europe's largest and most powerful civilization. After the Punic Wars Rome was already one of the biggest empires on the planet but its expansion continued with the invasions of Greece and Asia Minor. By 27 BC Rome had control over half of Europe as well as Northern Africa and large amounts of the Middle East. Rome also had a developed culture, building on the earlier Greek culture. From the time of Augustus to the Fall of the Western Empire, Rome dominated Western Eurasia, comprising the majority of its population.

Roman expansion began long before the state was changed into an Empire and reached its zenith under emperor Trajan with the conquest of Mesopotamia and Armenia in AD 113. The period of the "Five Good Emperors" saw a successions of peaceful years and the Empire was prosperous. Each emperor of this period was adopted by his predecessor. The Nerva–Antonine dynasty was a dynasty of seven consecutive Roman Emperors who ruled over the Roman Empire from 96 to 192. These Emperors are Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, and Commodus.

The last two of the "Five Good Emperors" and Commodus are also called Antonines. After his accession, Nerva, who succeeded Domitian, set a new tone: he restored much confiscated property and involved the Roman Senate in his rule. Starting in 101, Trajan undertook two military campaigns against the gold rich Dacia, which he finally conquered in 106 (see Trajan's Dacian Wars). In 112, Trajan marched on Armenia and annexed it to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Parthia, taking several cities before declaring Mesopotamia a new province of the empire, and lamenting that he was too old to follow in the steps of Alexander the Great. During his rule, the Roman Empire expanded to its largest extent, and would never again advance so far to the east. Hadrian's reign was marked by a general lack of major military conflicts, but he had to defend the vast territories that Trajan had acquired.

At this territorial peak, the Roman Empire controlled approximately 5,900,000 km² (2,300,000 sq.mi.) of land surface. Ancient Rome's influence upon the culture, law, technology, arts, language, religion, government, military, and architecture of Western civilization continues to this day.

See also: Daqin and Romano-Chinese relationsHunnic Empire

- 370-454

| Hunnic Empire |

|---|

Attila's imperial capital (approximate) Attila's empire (approximate) Non-Hunnic Regions |

Huns were nomadic people who were known for their hordes of mounted archers. Their language seems to be Turkic; but Mongolic, Yeniseian, Uralic etc., are also postulated. After 370 under a certain Balamber they founded an empire in the East Europe defeating Alans and Goths. They triggered the great migration which eventually caused the collapse of the West Roman Empire.

The death of Rugila in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda, in control of the united Hun tribes. Attila the Hun ruled of the Huns from 434 until his death in 453. Under his rule and leader of the Hunnic Empire, the empire stretched from Germany to the Ural River and from the Danube River to the Baltic Sea. Hunnic khagan Atilla invaded Europe. The rise of the Huns around 370 overwhelmed the Gothic kingdoms. Many of the Goths migrated into Roman territory in the Balkans, while others remained north of the Danube under Hunnic rule.

During Attila the Hun's rule, he was one of the most fearsome enemies of the Western and Eastern Roman Empire. He invaded the Balkans twice and marched through Gaul (modern France) as far as Orléans before being defeated at the Battle of Châlons. Although his invasion of Gaul was checked at Chalons, he appeared in North Italy in the next year. After Atilla’s death in 453, the Hunnic empire collapsed.

Medieval Powers

- 476-1492

- Middle Ages

Medieval Middle and Near East

Byzantine Empire

- 330 - 1453

| Byzantine Empire |

|---|

Western Roman Empire Eastern Byzantine Empire Outlying regions |

The Byzantine Empire is the name for the medieval eastern Roman Empire, which survived 1000 years after the fall of the western Roman Empire. The Byzantines managed to reconquer great parts of it. Ancient Roman cultural heritage survived there and gave birth to the Italian Renaissance after its capital, Constantinople, was captured by the Turks in the 15th century. The Byzantines were the only Europeans to produce fine silk which was an important source of their wealth along with trade.

Byzantium under the Justinian dynasty saw a period of recovery of former territories. The period is marked with internal strife within the Empire, from Ostrogoths, and from the Persians. The strength of the dynasty was shown under Justinian I, in which the territorial borders of the Empire were expanded because of numerous campaigns by his favored general, Belisarius. The western conquests began with Justinian sending his general to reclaim the former province of Africa from the Vandals who had been in control with their capital at Carthage. Their success came with surprising ease, but the major local tribes were subdued. In Ostrogothic Italy, the deaths of Theodoric the Great, his nephew and heir, and his daughter had left her murderer Theodahad on the throne despite his weakened authority. A small Byzantine expedition to Sicily was met with easy success, but the Goths soon stiffened their resistance, and victory did not come until later, when Belisarius captured Ravenna, after successful sieges of Naples and Rome.

Byzantium continued to be a major military power with a huge army and strong fleet, and was a major cultural and religious center. Byzantium was the stronghold of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and thus influenced many states. Byzantium fought against the Arabs to the south, the Bulgarians to the north and the Crusaders, who managed to seize Constantinople in 1204. The Byzantines restored their state in 1261, but its strength never recovered and it was eventually destroyed and replaced by the nascent Ottoman Empire in 1453.

Medieval Turkic Empires

Göktürk

Main article: Göktürk| Göktürk |

|---|

Göktürk region Outlying regions |

Turks, who were the residents around Altai mountains in Central Asia, founded a number of empires prior to their conversion to Islam. The Turkic Khaganate (or Göktürk, meaning Celestial Turk)(another possibility is "East Türk" since Blue (Gök) represent east direction in ancient Türks) was founded in 551 in what is now Kazakhstan and Mongolia by Bumin Khan of Ashina clan. Following a Turkish tradition, Bumin Khan ruled the east part of the empire and assigned his brother Istämi to the west part of the empire as his vassal. Bumin’s successor Muhan Khan defeated China and began controlling the prosperous silk road. Meanwhile, Istemi and his successors conquered Transoxania and Caucasus. It is one of Istemi's grandsons (Tong Yabgu) who founded another Turkic empire; the Khazarian Khaganate in the Caucasus. Another state emerged in the realm of Western Turks was that of Turgesh in west Turkistan. (Both Khazars and Turgesh fought against the invading Arabic armies in the 8th century). Although, the empire was briefly dominated by Tang China during 650s, Kutluk Khan, another member of Ashina clan was able to defeat China. In the early 8th century, during Bilge Khan’s reign, first Turkish monuments in Turkish alphabet were erected.(Orkhon monuments) In 744, Uyghurs, another branch of Turks replaced Turkish Khaganate in Central Asia.

Uyghur Khaganate

Main article: Uyghur KhaganateThe Uyghur Khaganate established itself as a major power in Central Asia the late 8th century. At their height, they controlled an area of land stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk to the Tibetan Plateau. They built their capital Ordu balik in modern Mongolia. Although they were replaced by their Kyrghyz vassals in 840s, they managed to survive in three smaller states. Those who were called Sari Uyghurs (yellow Uyghur) settled in Gansu (north China). Most Uyghurs settled in Xinjiang (west China). Some Uyghurs together with Karluks ( their former vassals in Transoxania, modern Uzbekistan), founded Karakhanid state which soon embraced Islam.

Great Seljuk empire

- 1040–1154

| Seljuk empire |

|---|

|

The name Seljuk refers to an Oghuz Turkic leader whose tribe had migrated from North (probably Khazar Khanette) to Khorosan where they embraced Islam., Seljuk’s grand sons after defeating Ghaznavids in 1040 founded an empire and decleared themselves to be the protectors of the caliph. Their empire with caliphs prestige, Turkish army and Persian bureaucracy proved to be one of the most powerful of states of 11th century. In 1071 after Alp Arslan of Seljuks defeated Byzantine army at Manzikert, Turks began to settle in Anatolia (Asiatic side of Turkey). But Great Seljuk Empire began to disintegrate in the second half of the 12th century. Soon, they were replaced by a number of states ruled by members of Seljuk house or by atabegs. The most important of these was the Sultanate of Rûm which continued up to 14th century and Khwarezmid Empire in Iran and Turkmenistan which fell prey to Mongols in 1220s.

Arab Caliphates

- 632 - 1258

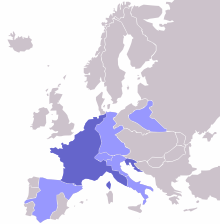

| Muslim conquests |

| Muhammad's Expansion (622-632) Patriarchal Expansion (632-661) Umayyad Expansion (661-750) |

In 622, a new world religion emerged, Islam, founded by Muhammad in Arabia. After his death, his successors began a century of rapid Arab expansion across most of the known world, establishing the Islamic Empire as one of the largest in the world.

See also: Muslim historyRashidun Caliphate

Main articles: Rashidun and Rashidun Caliphate

Under the Rashidun Caliphate, the newly united and religiously inspired Muslim Arabs invaded the powerful Sassanid Persian Empire during the Rashidun conquest of Persia and the Byzantine Empire during the Byzantine-Arab Wars. The war of conquest resulted in a complete conquest of the Sassanid Persian Empire and two-thirds of the Byzantine Empire. Within a decade, Rashidun caliphs controlled an empire stretching from the Indus River to the Atlas mountains. Khalid ibn Walid was responsible for most of the conquests on the Byzantine front. After a civil war in 657-661, the almost republic disintegrated and was succeeded by the Ummayad monarchy.

Umayyad Caliphate

Main article: UmayyadThe Umayyad Caliphate completed the Muslim expansion after conquering Roman North Africa, Visigothic Hispania, and a small part of the border of the Indian subcontinent and northwestern China. As a result, the Arab Empire became the largest empire the world had yet seen. However, Umayyad expeditions into the Frankish Kingdom and Byzantium were unsuccessful, as they were eventually stopped by the Bulgarians and Byzantines in 718 and the Franks in 732. Nonetheless, the Caliphate remained a huge military power with a mighty navy.

Abbasid Caliphate

Main articles: Abbasid and Islamic Golden Age| Abbasid Caliphate |

|---|

|

The period of the Abbasid Caliphate is considered the Golden Age of Islam. The empire was rich with flourishing trade across Asia, Europe and Africa. Its culture was thriving, influenced by the Persians, and boasted great achievements in its economy, arts, architecture, literature, mathematics, philosophy, science, and technology. Many cities grew with large populations, beautiful palaces and gardens such as Baghdad, which had a population of a million at its peak, as well as Damascus, Cairo and Cordoba. The Caliphate eventually diminished in size, and was further reduced during the Crusades. The Caliphate later disintegrated after invasions from the Mongol Empire from the east, ending with the sack of Baghdad in 1258.

Al-Andalus

Main article: Al-Andalus| Caliphate of Córdoba |

|---|

|

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to those parts of the Iberian Peninsula governed by Muslims, or Moors, at various times in the period between 711 and 1492. As a political domain or domains, it was successively a province of the Umayyad Caliphate initiated successfully by the Caliph Al-Walid I (711-750), the Emirate of Córdoba (c. 750-929), the Caliphate of Córdoba (929-1031), and finally the Caliphate of Córdoba's taifa (successor) kingdoms.

The Caliphate enjoyed immense prosperity throughout the 10th century. Abd-ar-Rahman III not only united al-Andalus, but brought the Christian kingdoms of the north, through force and diplomacy, under control. Abd-ar-Rahman stopped the Fatimid advance into Caliphate lands in Morocco and al-Andalus. This period of prosperity is marked by growing diplomatic relations with Berber tribes in North African, Christian kings from the north, with France and Germany, and Constantinople. The death of Abd-ar-Rahman III led to the rise of his 46 year old son Al-Hakam II in 961. Al-Hakam II more-or-less followed in his father's footsteps, occasionally dealing with a few disruptive Christian kings and North African rebels, though trying not to be too severe. Unlike his father, al-Hakam's dependence upon his advisers was more distinct.

Fatimid Caliphate

Main article: Fatimid Caliphate| Fatimid Caliphate |

|---|

|

The al-Fātimiyyūn was the Arab Shi'a dynasty that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Egypt, and the Levant from 5 January 909 to 1171, and established the Egyptian city of Cairo as their capital. The term Fatimite is sometimes used to refer to the citizens of this caliphate. The ruling elite of the state belonged to the Ismaili branch of Shi'ism. The leaders of the dynasty were also Shia Ismaili Imams, hence, they had a religious significance to Ismaili Muslims. They are also part of the chain of holders of the office of Caliph, as recognized by most Muslims. Therefore, this constitutes a rare period in history in which some form of the Shia Imamate and the Caliphate were united to any degree, excepting the Caliphate of Ali himself.

The Fatimids were known to a great extent for their exquisite arts. A type of ceramic, lustreware, was prevalent during the Fatimid period. Glassware and metalworking was also popular. Many traces of Fatimid architecture exist in Cairo today, the most defining examples include the Al Azhar University and the Al Hakim mosque. The Al Azhar University was the first university in the East. It was founded by Caliph Muizz and was one of the highest educational facilities of the Fatimid Empire.

Unlike other governments in the area, Fatimid advancement in state offices was based more on merit than on heredity. Members of other branches of Islam, like the Sunnis, were just as likely to be appointed to government posts as Shiites. Tolerance was extended to non-Muslims such as Christians, and Jews, who occupied high levels in government based on ability.

The reliance on the Iqta' system ate into Fatimid central authority, as more and more the military officers at the further ends of the empire became semi-independent and were often a source of problems.

See also: Emirate of SicilyAyyubid Sultanate

- 1171–1246

| Ayyubid Sultanate |

|---|

|

The Ayyubid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Kurdish origin, founded by Saladin and centered in Egypt. The dynasty ruled much of the Middle East during the 12th and 13th centuries CE. The Ayyubid family, under the brothers Ayyub and Shirkuh, originally served as soldiers for the Zengids until they supplanted them under Saladin, Ayyub's son. The Ayyubid Sultanate in the Middle East managed to rebuild the weakened Arab State. In 1174, Saladin proclaimed himself Sultan following the death of Nur al-Din. The Ayyubids spent the next decade launching conquests throughout the region and by 1183, the territories under their control included Egypt, Syria, northern Mesopotamia, Hejaz, Yemen, and the North African coast up to the borders of modern-day Tunisia. Most of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond Jordan River fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders regained control of Palestine's coastline in the 1190s.

After the death of Saladin, his sons contested control over the sultanate, but Saladin's brother al-Adil eventually established himself as Sultan in 1200. In the 1230s, the Ayyubid rulers of Syria attempted to assert their independence from Egypt and remained divided until Egyptian Sultan as-Salih Ayyub restored Ayyubid unity by taking over most of Syria, excluding Aleppo, by 1247. During their relatively short tenure, the Ayyubids ushered in an era of economic prosperity in the lands they ruled and the facilities and patronage provided by the Ayyubids led to a resurgence in intellectual activity in the Islamic world. This period was also marked by an Ayyubid process of vigorously strengthening Sunni Muslim dominance in the region by constructing numerous madrasas (schools) in their major cities.

Bahri Mamluks Empire

- 1250–1380

| Mamluk Empire |

|---|

|

The Bahriyya Mamluks (Bahri dynasty) was a Mamluk dynasty of mostly Kipchak Turkic origin that ruled Egypt, the Levant, and some parts of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Libya, from 1250 to 1382. Their name means 'of the sea', referring to the location of their original residence on Al-Rodah Island in the Nile (Baḥr an-Nīl) in Cairo at the castle of Al-Rodah which was built by the Ayyubid Sultan as-Salih Ayyub

Under Saladin and the Ayyubids of Egypt, the power of the mamluks increased until they claimed the sultanate in 1250, ruling as the Mamluk Sultanate. Mamluk regiments constituted the backbone of the late Ayyubid military. Each sultan and high-ranking amir had his private corps, and the sultan as-Salih Ayyub (r. 1240-1249) had especially relied on this means to maintaining power. His mamluks, numbering between 800 and 1,000 horsemen, were called the Bahris, after the Arabic word bahr (بحر), meaning sea or large river, because their barracks were located on the island of Rawda in the Nile. They were mostly drawn from among the Kipchak Turks who controlled the steppes north of the Black Sea.

The Bahriyya were succeeded by the Burji dynasty, another group of Mamluks. Tehj Burji saw a turbulent and short-lived Sultanate. Political power-plays often became important in designating a new sultan.

Bulgaria

- 800s - 1000s

| Bulgarian Empire |

|---|

|

In 681 the Bulgarians established a powerful state which played a major military and cultural role in Medieval Europe. Bulgaria decisively defeated the Arabs in the battle before Constantinople (718) and stopped the Arab invasion in the eastern parts of the continent effectively stopping the migrations of the barbarian tribes (Pechenegs, Magyars, Khazars) further to the west. It destroyed the Avars Khanate in 806.

With the adoption of Christianity and the invention of the Cyrillic Alphabet, the Bulgarian Empire became the cultural and spiritual centre of the whole Slavic world. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church became the first National Church in Europe to gain its independence in 927 with its own Patriarch. The Bulgarian Empire reached its biggest size in the early 10th century stretching from the Black Sea to Bosnia.

The medieval Bulgarian state was restored as the Second Bulgarian Empire after a successful uprising of two nobles from Tarnovo, Asen and Peter, in 1185, and existed until it was conquered during the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans in the late 14th century, with the date of its subjugation usually given as 1396 or 1422. Under Ivan Asen II in the first half of the 13th century it gradually recovered much of its former power, though this did not last long due to internal problems and foreign invasions.

Georgia

- 1184–1225

| Kingdom of Georgia |

|---|

|

The unified monarchy maintained its precarious independence from the Byzantine and Seljuk empires throughout the 11th century, and flourished under David IV the Builder (1089–1125), who repelled the Seljuk attacks and essentially completed the unification of Georgia with the re-conquest of Tbilisi in 1122.

With the decline of Byzantine power and the dissolution of the Great Seljuk Empire, Georgia became one of the pre-eminent nations of the Christian East, her pan-Caucasian empire stretching, at its largest extent, from North Caucasus to northern Iran, and westwards into Asia Minor. In spite of repeated incidents of dynastic strife, the kingdom continued to prosper during the reigns of Demetrios I (1125–1156), George III (1156–1184), and especially, his daughter Tamar (1184–1213). With the death of George III the main male line went extinct and the dynasty was continued by the marriage of Queen Tamar with the Alan prince David Soslan of reputed Bagratid descent.

Ghaznavid Empire

- 960s - 998

| Ghaznavid Empire |

|---|

|

The Ghaznavids were a Persianate Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin which existed from 975 to 1187 and ruled much of Persia, Transoxania, and the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent. The Ghaznavid state was centered in Ghazni, a city in present Afghanistan. Due to the political and cultural influence of their predecessors - that of the Persian Samanid Empire - the originally Turkic Ghaznavids became thoroughly Persianized.