| Revision as of 11:06, 24 July 2013 view sourceKingstowngalway (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users21,911 edits →External links← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:07, 24 July 2013 view source Kingstowngalway (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users21,911 edits →External linksNext edit → | ||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 148: | Line 149: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 11:07, 24 July 2013

| Amon Leopold Göth | |

|---|---|

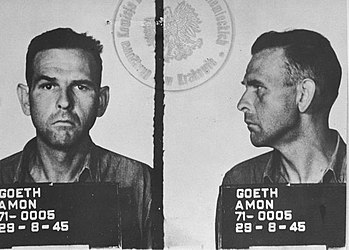

Amon Leopold Göth's mug shot in 1945. Amon Leopold Göth's mug shot in 1945. | |

| Born | (1908-12-11)December 11, 1908 Vienna, Austria-Hungary (now Austria) |

| Died | September 13, 1946(1946-09-13) (aged 37) Kraków, Poland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1930–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | NSDAP #510,764 SS #43,673 |

| Unit | |

| Commands | Arbeitslager KL-Płaszów |

| Other work | SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt |

Amon Leopold Goeth (represented in German as Göth pronounced [ˈɡøːt]) (11 December 1908 – 13 September 1946) was an SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain) and the commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp in Płaszów in German-occupied Poland during World War II. He was tried as a war criminal after the war. After the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland at Kraków found him guilty of murdering tens of thousands of people, he was executed by hanging not far from the former site of the Płaszów camp. The film Schindler's List depicts his practice of shooting camp internees.

Early life and career

Goeth was born on 11 December 1908 in Vienna, then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to a family in the book publishing industry. Goeth joined a Nazi youth group at age 17 and was a member of the antisemitic nationalist paramilitary group Heimwehr (Home Guard) from 1927 to 1930. He dropped his membership to join the Austrian branch of the Nazi Party, being assigned the party membership number 510,764 in September 1930. Goeth joined the Austrian SS in 1930 and was appointed an SS-Mann with the SS Number 43,673.

Goeth served with the SS Truppe Deimel and Sturm Libardi in Vienna until January 1933, when he was promoted to serve as adjutant and platoon leader of the 52nd SS Standarte, a regimental-sized unit. He was soon promoted to SS-Scharführer (squad leader). He fled to Germany when his illegal activities, including obtaining explosives for the Nazi party, made him a wanted man. The Austrian Nazi Party was declared illegal in Austria on 19 June 1933, so they set up operations in exile in Munich. From this base, Goeth smuggled radios and weapons into Austria and acted as a courier for the SS. He was arrested in October 1933 by the Austrian authorities and was released for lack of evidence in December 1933. He was again detained after the assassination of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in a failed Nazi coup attempt in July 1934. He escaped custody and fled to the SS training facility at Dachau, next to the infamous Dachau Concentration Camp. He temporarily quit the Nazi party until 1937 and returned home to help his parents with their publishing house. He married on the recommendation of his parents, but was divorced after only a few months.

Goeth returned to Vienna shortly after the Anschluss in 1938 and resumed his party activities. He married Anny Geiger in a civil SS ceremony on October 1938. The couple had two boys who were born in 1939 and 1940, and a daughter who did not survive childhood. The couple maintained a permanent home in Vienna throughout World War II. Initially assigned to SS-Standarte 89, Goeth was transferred to SS-Sturmbann 1/11 at the start of the war and was promoted to SS-Oberscharführer (staff sergeant) in early 1941. He soon gained a reputation as a seasoned administrator in the Nazi efforts to isolate and relocate the Jewish population of Europe as an Einsatzführer (action leader) and financial officer for the Reichskommissariat for the Strengthening of German Nationhood (German: Reichskommissariat für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums; RKFDV). He was commissioned to the rank of SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) on 14 July 1941 and was transferred to Lublin in the summer of 1942.

Płaszów

On 11 August 1942, Goeth departed from his current position to join the staff of SS-Brigadeführer Odilo Globočnik, the SS and Police Leader of the Kraków area. He was appointed a regular SS officer of the Concentration Camp service, and on 11 February 1943 was assigned to construct and command a forced labour camp at Płaszów. The camp took one month to construct using forced labour and, on 13 March 1943, the Jewish ghetto of Kraków was closed down (liquidated), with the surviving inhabitants imprisoned in the new forced labor camp. Approximately 2,000 people died during the evacuation.

File:Amon Göth at his balkony Płaszów 1943.jpgGöth on the balcony of his house in Płaszów wielding a rifle, summer 1943 The balcony in Płaszów (2008). Göth could not aim from there, because the villa sits at the foot of a hill. Instead, he used to step outside the house to shoot while wearing his Tyrolean hat marking the intention of hunting humans. It was the signal for seasoned prisoners to attempt to hide.

The balcony in Płaszów (2008). Göth could not aim from there, because the villa sits at the foot of a hill. Instead, he used to step outside the house to shoot while wearing his Tyrolean hat marking the intention of hunting humans. It was the signal for seasoned prisoners to attempt to hide.

On 3 September 1943 Goeth was given the further task of shutting down the ghetto at Tarnów, with a population of about 10,000 people, where an unknown number of people perished having been killed on the spot; others died through asphyxiation during transport by rail or were exterminated in death camps, in particular at Auschwitz.

On 3 February 1944 Goeth closed down the concentration camp at Szebnie by ordering the inmates to be murdered on the spot or deported to other camps and to Auschwitz, again resulting in over ten thousand deaths.

By April 1944, Goeth had been promoted to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain), having received a double promotion and thus skipping the rank of SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant). He was also appointed a reserve officer of the Waffen-SS, a branch of the SS. His assignment as Commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów Labour Camp continued, now under the direct authority of the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt, also known as the SS Economics and Administration Office.

Goeth believed that the Jews themselves should pay for their own executions, so on 11 May 1942, in the small town of Szczebrzeszyn, the Gestapo ordered the Jewish council to pay 2,000 złoty and 3 kilograms of coffee to cover the expenses for the ammunition used to kill the Jews.

During his tenure as commander of Płaszów, Goeth tortured and murdered prisoners on a daily basis. Goeth is believed to have personally killed more than 500 imprisoned Jews and sent thousands more to be executed on Hujowa Górka, a large hill that was used for mass killings along Płaszów's grounds. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindler Jews, said: "When you saw Goeth, you saw death." According to Płaszów survivor Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig:

"As a survivor I can tell you that we are all traumatized people. Never would I, never, believe that any human being would be capable of such horror, of such atrocities. When we saw him from a distance, everybody was hiding, in latrines, wherever they could hide. I can't tell you how people feared him."

Goeth forced Mieczysław "Mietek" Pemper, who was Jewish, to work as his personal secretary and stenographer in Płaszów. In his book "The Road to Rescue: The Untold Story of Schindler's List", Pemper says that the job allowed him to collect information and thus help Oskar Schindler to save more than 1,200 Jews. Mietek Pemper is known to this day as the man who compiled Schindler's List.

Goeth spared the life of Jewish prisoner Natalia Hubler (later famous as Natalia Karp) and that of her sister, after hearing her play a nocturne by Chopin on the piano the day after she arrived at the Płaszów camp.

Dismissal and capture

On 13 September 1944 Goeth was relieved of his position as Commandant of Płaszów and was assigned to the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt. Around November 1944 in Vienna, Goeth was charged with theft of Jewish property (which, according to Nazi legislation, belonged to the state), and was arrested by the Gestapo. He was scheduled for an appearance before SS judge Georg Konrad Morgen, but due to the progress of World War II and Germany's looming defeat, a court martial was never assembled and the charges against him were summarily dismissed.

He was next assigned to Bad Tölz, Germany, where he was quickly diagnosed by SS doctors as suffering from mental illness and diabetes. He was committed to a mental institution. He remained there until he was arrested by the United States military in May 1945. At the time of his arrest, Goeth claimed to have been recently promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer and, during later interrogations, several documents listed him as "SS-Major Göth". Rudolf Höss was also of the opinion that Goeth had been promoted and, when called to give testimony at Goeth's trial, indicated that Goeth was an SS-Major in the Concentration Camp service.

Goeth's service record, however, does not support the claim of a late war promotion and he is listed in most texts as having held the rank of only SS-Hauptsturmführer, equivalent to captain.

Execution

After the war, the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland in Kraków held his trial between August 27 and September 5, 1946. Goeth was found guilty of imprisonment, torture and extermination of Jews, Poles as well as other nationals, and of personally killing, maiming and torturing a substantial, albeit unidentified number of people. He was sentenced to the death penalty and was hanged on September 13, 1946 at the Montelupich Prison in Kraków, "one of the most terrible Nazi prisons in occupied Poland" used by Gestapo throughout World War II, located not far from the former site of the Płaszów camp. At his execution, Goeth's hands were tied behind his back. Contrary to popular belief, Goeth's hanging was not filmed. There's a record in existence showing the execution of war criminal Ludwig Fischer conducted on March 8, 1947 in Warsaw, which is sometimes mislabeled by the media as his.

Family

See also: Inheritance (2006 film)Goeth was married and divorced twice. His first marriage was to Olga Janauschek in January 1934. They were divorced in July 1936. His second marriage was to Anny Geiger in October 1938, which ended in 1944. Soon after his second marriage ended, Goeth was engaged to Ruth Irene Kalder, (nicknamed "Majola" in the Płaszów camp during her stay in Goeth's "Red Villa"), who had taken Goeth's name shortly after his death. Through these relationships, Goeth had two sons and two daughters. With Olga Janauschek, Goeth had his first child, a boy named Peter, who died seven months after his birth from a diphtheria infection. Goeth had two children with Anny Geiger, a daughter named Ingeborg and a son named Werner. Goeth's last child was a daughter named Monika (chosen mainly from Goeth's childhood nickname, "Mony") whom he had by Ruth Irene Kalder. Monika was born on 23 October 1945, ten months before his execution.

In popular culture

Goeth's actions at Płaszów Labor Camp became internationally known through his depiction by British actor Ralph Fiennes in the 1993 film, Schindler's List. In a subsequent interview, Fiennes recalled:

Evil is cumulative. It happens. People believe that they’ve got to do a job, they’ve got to take on an ideology, that they’ve got a life to lead; they’ve got to survive, a job to do, it’s every day inch by inch, little compromises, little ways of telling yourself this is how you should lead your life and suddenly then these things can happen. I mean, I could make a judgement myself privately, this is a terrible, evil, horrific man. But the job was to portray the man, the human being. There’s a sort of banality, that everydayness, that I think was important. And it was in the screenplay. In fact, one of the first scenes with Oskar Schindler, with Liam Neeson, was a scene where I’m saying, 'You don’t understand how hard it is, I have to order so many—so many meters of barbed wire and so many fencing posts and I have to get so many people from A to B.' And, you know, he’s sort of letting off steam about the difficulties of the job.

Fiennes won a BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and his portrayal ranked 15th on AFI's list of the top 50 film villains of all time. He ranks as the highest non-fiction villain. When Płaszów survivor Mila Pfefferberg was introduced to Fiennes on the set of the film, she began to shake uncontrollably, as Fiennes, attired in full SS dress uniform, reminded her of the real Amon Goeth. At the film's climax, Goeth's hanging is dramatized. However, he is incorrectly shown patting his hair in place and saying "Heil Hitler" moments before an officer in the People's Army of Poland kicks a chair out from under him.

In 2002, Amon Goeth's daughter Monika Goeth Hertwig published her memoirs under the name Ich muß doch meinen Vater lieben, oder? ("But I have to love my father, don't I?"). Monika described the subsequent life of her mother, Ruth Kalder Goeth, who unconditionally glorified her fiancé until confronted with his role in the Holocaust. Ruth committed suicide in 1983, shortly after giving an interview in Jon Blair's documentary Schindler. Monika Hertwig's experiences in dealing with her father's crimes are detailed in Inheritance, a 2006 documentary directed by James Moll. Appearing in the documentary is Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig, one of Amon Goeth's former housemaids. The documentary details the meeting of the two women at the Płaszów memorial site in Poland. In a subsequent interview, Jonas-Rosenzweig recalled,

"It's hard for me to be with her because she reminds me a lot of, you know...she's tall, she has certain features. And I hated him so. But she is a victim. And I think it's important because she is willing to tell the story in Germany. She told me people don't want to know, they want to go on with their lives. And I think it's very important because there's a lot of children of perpetrators, and I think she's a brave person to go on talking about it, because it's difficult. And I feel for Monika. I am a mother, I have children. And she is affected by the fact that her father was a perpetrator. But my children are also affected by it. And that's why we both came here. The world has to know, to prevent something like this from happening again."

Monika Hertwig has also appeared in a recent documentary film called Hitler's Children, directed and produced by Chanoch Zeevi who is an Israeli documentary maker. In the documentary, Monika and other close relatives of infamous Nazi leaders describe their feelings, relationships and memories of their relations.

Summary of SS career

- SS number: 43673

- Nazi Party number: 510764

- Primary positions: Lagerkommandant, Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp

- Waffen-SS service: SS-Hauptsturmführer der Reserve

Dates of rank

- SS-Mann: 1930

- SS-Oberscharführer: 1941

- SS-Untersturmführer: 14 July 1941

- SS-Hauptsturmführer: 1 August 1943

- SS-Hauptsturmführer der Reserve der Waffen-SS: 20 April 1944

Awards

Source: SS Service Record of Amon Göth – National Archives & Records Administration, College Park, Maryland

References

- Crowe 2004, p. 217.

- Crowe 2004, p. 218–220.

- Crowe 2004, pp. 220–221.

- Crowe 2004, pp. 221–223.

- Crowe 2004, p. 223.

- Crowe 2004, pp. 224–226.

- ^ Crowe, David (2007). Oskar Schindler. Basic Books. p. 226. ISBN 0465002536. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Bartosz T. Wieliński (10.07.2012). "Amon Göth myśliwy z KL Płaszów (Amon Göth, the hunter from KL Płaszów)". Column alehistoria (in Polish). Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - Jacek Bracik, Józef Twaróg (2003). "Obóz w Szebniach (Camp in Szebnie)" (Internet Archive) (in Polish). Region Jasielski, nr 3 (39). Retrieved July 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "The SS: A Government in Waiting". Yizkor Book Project. JewishGen. 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Jonas, Helen (26 February 2009). "Voices on Antisemitism – A Podcast Series". ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- http://www.scrapbookpages.com/Poland/Plaszow/Plaszow03A.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/19/world/europe/19pemper.html

- Charters, David. "Natalia Karp". LiverpoolDailyPost.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- SS service record of Amon Göth, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

- Andrzej Rzepliñski (March 25, 2004; Lyon, France). "Prosecutionof Nazi Crimes in Poland in 1939–2004" (PDF file, direct download 140 KB). The First International Expert Meeting on War Crimes, Genocide, and Crimes against Humanity. International Criminal Police Organization – InterpolGeneral. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Paweł Brojek (Nov 24, 2012), Pierwszy proces oświęcimski (The First Auschwitz Trial). Portal Prawy.pl. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- MWP. "August 27, 1946: Polish tribunal sentenced SS-Hauptsturmführer Göth to death by hanging". Major events after May 9, 1945 (in Polish). Muzeum Wojska Polskiego (Museum of the Polish Army). Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- Film documentary record of execution of Ludwig Fischer conducted on March 8, 1947 in Warsaw is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Goeth execution. See: Isabelle Clarke and Danielle Costelle, La Traque des Nazis 1945–2005, soixante ans de traque. Template:Fr icon

- Becky Evans, Historians claim video of camp commander being hanged is not him. Daily Mail Online, March 21, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- Fiennes, Ralph (4 March 2010). "Voices on Antisemitism – A Podcast Series". ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Corliss, Richard (21 February 1994). "The Man Behind the Monster". Time Magazine. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- Bülow, Louis (2007). "The Nazi Butcher: Amon Goeth". Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Kessler, Matthias (2002). Ich muß doch meinen Vater lieben, oder? (in German). Eichborn. ISBN 978-3821839141.

- "Inheritance". Public Broadcasting Service. 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Voices on Antisemitism | Transcript". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- "Hitler's Children". Chanoch Ze'evi. 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

Biography

- Crowe, David M. (2004). Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-465-00253-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Wien, Johannes Sachslehner, Styria Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-222-13233-9 (German language)

External links

- The Trial of Amon Goeth

- An Interview with Monika Goeth Hertwig.

- Voices on Antisemitism' Interview with Helen Jonas from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Ralph Fiennes from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- 1908 births

- 1946 deaths

- Austrian mass murderers

- Austrian murderers

- Austrian Nazis convicted of war crimes

- Austrian people convicted of crimes against humanity

- Austrian people executed abroad

- Austrian people executed by hanging

- Executed Nazi concentration camp personnel

- Filmed executions

- Holocaust perpetrators

- Kraków Ghetto

- Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp personnel

- Nazi concentration camp commandants

- Nazis executed in Poland

- People from Kraków

- People from Vienna

- SS officers

- People executed by Poland by hanging