| Revision as of 23:36, 16 June 2006 edit68.32.11.74 (talk) →American exceptionalism← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:10, 17 June 2006 edit undoHorses In The Sky (talk | contribs)1,490 edits →Definition of empireNext edit → | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

| ==Definition of empire== | ==Definition of empire== | ||

| In one sense, the U.S. is not an empire, because it lacks a legal ], ], ], or other ] ]. In another sense, the U.S. satisfies the definition of an empire, because it possesses ] over territories which it has not ] as states, such as ], ], ] and in the past the ].{{ref|neutraluses}} | In one sense, the U.S. is not an empire, because it lacks a legal ], ], ], or other ] ]. In another sense, the U.S. satisfies the definition of an empire, because it possesses ] over territories which it has not ] as states, such as ], ], ] and in the past the ] and the ].{{ref|neutraluses}} | ||

| Controversy exists over whether the U.S. consistently behaves like an empire across the world, and so can be fairly described as one. The term ] was coined in the mid-1800s to describe empire-like behavior, carried out by states which might or might not be formal empires.{{ref|Oxford1}} The ] gives three definitions of imperialism: | Controversy exists over whether the U.S. consistently behaves like an empire across the world, and so can be fairly described as one. The term ] was coined in the mid-1800s to describe empire-like behavior, carried out by states which might or might not be formal empires.{{ref|Oxford1}} The ] gives three definitions of imperialism: | ||

Revision as of 19:10, 17 June 2006

| History of the United States expansion and influence |

|---|

| Colonialism |

|

|

| Militarism |

|

|

| Foreign policy |

|

| Concepts |

- This article is about views of the historical expansionism and current international influence of the United States. For other uses, please see American Empire (disambiguation). For a history of overseas United States territorial acquisitions, see History of United States overseas expansion.

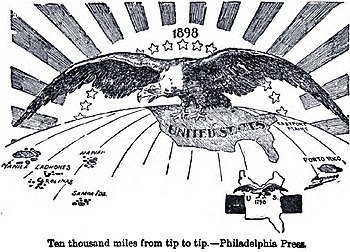

American Empire, and related phrases such as U.S. hegemony, etc., are terms sometimes used to describe the historical expansionism and the current political, economic, and cultural influence of the United States on a global scale.

They are usually part of a politically charged debate which involves three basic questions:

- Is the United States currently an empire?

- If the United States is an empire, when did it become one?

- If the United States is an empire, is that good or bad?

However, there are also more neutral uses of the term.

Definition of empire

In one sense, the U.S. is not an empire, because it lacks a legal emperor, king, despot, or other hereditary head of state. In another sense, the U.S. satisfies the definition of an empire, because it possesses sovereignty over territories which it has not annexed as states, such as Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam and in the past the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands and the Philippines.

Controversy exists over whether the U.S. consistently behaves like an empire across the world, and so can be fairly described as one. The term imperialism was coined in the mid-1800s to describe empire-like behavior, carried out by states which might or might not be formal empires. The Oxford English Dictionary gives three definitions of imperialism:

- 1. An imperial system of government; the rule of an emperor, esp. when despotic or arbitrary.

- 2. The principle or spirit of empire; advocacy of what are held to be imperial interests.

- 3. Used disparagingly. In Communist writings: the imperial system or policy of the Western powers. Used conversely in some Western writings: the imperial system or policy of the Communist powers.

Debate exists over whether the U.S. is an empire in the politically-charged sense of the latter two definitions.

However, some have argued that this use of the term is an abuse of language. Historian Stuart Creighton Miller argues that the overuse and abuse of the term "imperialism" makes it nearly meaningless as an analytical concept. Historian Archibald Paton Thorton wrote that "imperialism is more often the name of the emotion that reacts to a series of events than a definition of the events themselves. Where colonization finds analysts and analogies, imperialism must contend with crusaders for and against."

American exceptionalism

Historian Stuart Creighton Miller points out that the question of US imperialism has been the subject of agonizing debate ever since the United States acquired formal empire at the end of the nineteenth century during the Spanish-American war. Miller argues that this agony is because of America’s sense of innocence, produced by a kind of "immaculate conception" view of America's origins. When European settlers came to America they miraculously shed their old ways upon arrival in the New World, as one might discard old clothing, and fashioned new cultural garments based solely on experiences in a new and vastly different environment. Miller believes that school texts, patriotic media, and patriotic speeches on which Americans have been reared do not stress the origins of America's system of government, that these sources often omit or downplay that the "United States Constitution owes its structure as much to the ideas of John Calvin and Thomas Hobbes as to the experiences of the Founding Fathers; that Jeffersonian thought to a great extent paraphrases the ideas of earlier Scottish philosophers; and that even the allegedly unique frontier egalitarian has deep roots in seventeenth century English radical traditions." Philosopher Douglas Kellner traces the identification of American exceptionalism as a distinct phenomenon back to 19th century French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, who concluded by agreeing that the U.S., uniquely, was "proceeding along a path to which no limit can be perceived."

American exceptionalism is popular among people within the US, but its validity and its consequences are disputed. Miller argues that US citizens fall within three schools of thought about the question whether the United States is imperialistic:

- The tendency of highly patriotic Americans is to deny such abuses and even assert that they could never exist in their country.

- At the other end of the scale, overly self-critical Americans tend to exaggerate the nation’s flaws, failing to place them in historical or worldwide contexts.

- In the middle are Americans who assert that "Imperialism was an aberration."

First school of thought: "Empire is at the heart of US foreign policy"

Since the Spanish-American War, Anti-imperialist, Marxists and New Left writers tend to view imperialism as an unmitigated evil. US imperialism, in their view, traces its beginning not to the Spanish-American war, but to Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory, or even to the genocide of Native Americans prior to the American Revolution, and continues to this day. Historian Sidney Lens argues that "the United States, from the time it gained its own independence, has used every available means—political, economic, and military—to dominate other nations." Some critics of imperialism have a more positive view of American's early era, however; prominent conservative writer Patrick Buchanan argues that the modern United States's drive to empire is "far from what the Founding Fathers had intended the young Republic to become." This latter point of view is often identified with American isolationism, in the tradition of either the Old Right (Buchanan), or libertarianism (for example, Justin Raimondo).

Lens describes American exceptionalism as a myth, which allows any number of "excesses and cruelties, though sometimes admitted, usually regarded as momentary aberrations." Linguist and left-wing political critic Noam Chomsky argues that it is the result of a systematic strategy of propaganda, maintained by an "elite domination of the media" which allows it to "fix the premises of discourse and interpretation, and the definition of what is newsworthy in the first place, and they explain the basis and operations of what amount to propaganda campaigns."

This critical historical view is usually continued to present US foreign policy. Historian Andrew Bacevich, drawing on the work of Charles Beard and William Appleman Williams, argues that the end of the Cold War did not mark the end of an era in US history, because US foreign policy did not fundamentally change after the Cold War. US foreign policy has long been driven by the desire to expand access to foreign markets in order to benefit the domestic economy. The moralistic reasons given for American foreign intervention mask the true economic reasons, and Bacevich warns that US economic imperialism (in the guise of globalization) may not be in the best interests of the United States.

This is a common extension of the critique of American empire; Buchanan and, from the opposite side of the political spectrum, prominent left-wing writer Tariq Ali, argue independently but similarly that acts of terrorism against the United States, such as the September 11, 2001 attacks, are the direct result of the U.S.'s ill-fated attempts to intervene in places where it should never have been involved in the first place. Ali claims that "the reasons are really political. They see the double standards applied by the West: a ten-year bombing campaign against Iraq, sanctions against Iraq which have led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children, while doing nothing to restrain Ariel Sharon and the war criminals running Israel from running riot against the Palestinians. Unless the questions of Iraq and Palestine are sorted out, these kids will be attracted to violence regardless of whether Osama bin Laden is gotten dead or alive."

Ethnic studies professor Ward Churchill is almost alone, however, in extending this critique further to argue that at least some of the victims of the 9/11 attacks - the "little Eichmanns" who "formed a technocratic corps at the very heart of the US' global financial empire – the 'mighty engine of profit' to which the military dimension of U.S. policy has always been enslaved" - deserved their fates. A different extension is more common; many critics of US imperialism argue, like Marxist sociologist John Bellamy Foster, that the United States' sole-superpower status makes it now the most dangerous world imperialist.

US foreign interventions

In support of the thesis that the United States is an empire, numerous foreign interventions are often described as products of imperialism, including:

- The massacre or the forced diaspora of Native Americans, for example in the Trail of Tears (1831, 1838);

- The Mexican-American War of 1848 and subsequent annexation of Mexican territory;

- The alleged support of the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani in early 1893, the attempt to reinstate the queen in late 1893, and the subsequent annexation of Hawaii in 1898;

- The Spanish-American War in 1898 and the resulting occupation of Cuba, annexation of Puerto Rico, and Philippine-American War (1899-1913);

- Numerous interventions and gunboat diplomacy in Latin America justified by the Monroe Doctrine in countries such as Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua during the late 19th century and early 20th century

- Intervention in the First World War (1917-1918) and then subsequent invasion of Russia (1918-1920);

- Division of the world with the Soviet Union into zones of control after the Second World War, as enforced for example by intervention in the Greek Civil War (1946-1949) and in the Korean War from 1950-1953;

- Cold War covert operations in numerous countries including the removal of Iran's Prime Minister Mossadegh via the 1953 Operation Ajax and assistance in the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende in 1973;

- The Vietnam War from the early 1960s to 1973 and the bombing of Cambodia during the war;

- Participation in NATO intervention in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s;

- Intervention in El Salvador and Nicaragua in the early 1980s, sanctions against Cuba, the invasion of Panama in 1989 and intervention in Haiti in 2005-6;

- Participation in the Gulf War in 1990-1991, intervention in Afghanistan from 2001, and participation in the Iraq War from 2003 onward.

This history is used by some on the Left, such as Chomsky, Foster, Lens, and historian Howard Zinn, to argue that US capitalism is intrinsically imperialistic - a theory which may take a Leninist form, as for Tariq Ali. Others, such as left-wing ex-CIA consultant Chalmers Johnson, or most right-leaning opponents of empire, make a more limited critique, tracing the roots of empire to the "military-industrial complex" warned against by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Second school of thought: "US empire never existed"

For many citizens of the United States, part of patriotism is defending the historical role of the US against allegations of imperialism or other evil. This is especially common among prominent mainstream political figures; Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, for example, has said "we don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been." The United States, on this view, is genuinely exceptional, uniquely benevolent among world powers through history.

Ronald Radosh of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies argues that the United States' entrance into the Second World War, against Adolf Hitler's Germany is evidence that the US ability to intervene militarily abroad is crucial to preserving freedom and preventing genocide. Radosh claims that opponents of US imperialism are hypocrites, ignoring the greater crimes of states such as the Soviet Union because of an irrational prejudice against the United States, and/or appeasers, whose fear of exercising military power will only lead to larger and bloodier wars, as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's led to the rise of Hitler.

Taking on a harder case, against one of the most widely-accepted examples of imperialism, conservative military historian Max Boot argues that the United States altruistically went to war with Spain to liberate Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos from their tyrannical yoke. If US troops lingered on too long in the Philippines, it was to protect the Filipinos from European predators waiting in the wings for American withdrawal and to tutor them in American-style democracy. In the Philippines the US followed its usual pattern; "the United States would set up a constabulary, a quasi-military police force led by Americans and made up of local enlisted men. Then the Americans would work with local officials to administer a variety of public services, from vaccinations and schools to tax collection. American officials, though often resented, usually proved more efficient and less venal than their native predecessors... Holding fair elections became a top priority because once a democratically elected government was installed, the Americans felt they could withdraw."

Boot argues that this was far from "the old-fashioned imperialism bent on looting nations of their natural resources." Just as with Iraq and Afghanistan, "some of the poorest countries on the planet," in the early 20th century "the United States was least likely to intervene in those nations (such as Argentina and Costa Rica) where American investors held the biggest stakes. The longest occupations were undertaken in precisely those countries--Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic--where the United States had the smallest economic stakes... Unlike the Dutch in the East Indies, the British in Malaya, or the French in Indochina, the Americans left virtually no legacy of economic exploitation."

However, extensive war crimes by US soldiers in the Philippines, conducted as matters of policy, have been well documented. General Jacob H. Smith told his officers, "I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States." While Boot downplays the relative significance of these events, Stuart Creighton Miller claims that this patriotic interpretation is no longer heard very often by historians.

The benevolent empire

But Max Boot, in fact, is willing to use the term "imperialism" to describe United States policy, not only in the early 20th century but "since at least 1803," though this is primarily a difference in terminology, since he still argues that US foreign policy has been consistently benevolent. Boot is not alone; as Republican columnist Charles Krauthammer puts it, "People are now coming out of the closet on the word 'empire.'" This embrace of empire is made by many neoconservatives, including political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski, historian Paul Johnson, and writers Dinesh D'Souza and Mark Steyn. It is also made by some liberal hawks, such as Michael Ignatieff.

For example, historian Niall Ferguson argues that the United States is an empire, but believes that this is a good thing. Ferguson has drawn parallels between the British Empire and the imperial role of the United States in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, though he describes the United States' political and social structures as more like those of the Roman Empire than of the British. Ferguson argues that all these empires have had both positive and negative aspects, but that the positive aspects of the US empire will, if it learns from history and its mistakes, greatly outweigh its negative aspects.

Third school of thought: "Empire was an aberration"

Another point of view admits United States expansion overseas as imperialistic, but sees this imperialism as a temporary phenomenon, a corruption of American ideals or the relic of a past historical era. Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis argues that Spanish-American War expansionism was a short lived imperialistic impulse and "a great aberration in American history," a very different form of territorial growth than that of earlier American history. Historian Walter LaFeber sees the Spanish-American War expansionism not as an aberration but as a culmination of United States expansion westward. But both agree that the end of the occupation of the Philippines marked the end of US empire - they deny that present United States foreign policy is imperialist.

Right-wing historian Victor Davis Hanson argues that the US doesn't pursue world domination, but maintains worldwide influence by a system of mutually beneficial exchanges; "If we really are imperial, we rule over a very funny sort of empire... The United States hasn't annexed anyone's soil since the Spanish-American War... Imperial powers order and subjects obey. But in our case, we offer the Turks strategic guarantees, political support — and money... Isolationism, parochialism, and self-absorption are far stronger in the American character than desire for overseas adventurism."

Liberal internationalists argue that even though the present world order is dominated by the United States, the form taken by that dominance is not imperial. International relations scholar John Ikenberry argues that international institutions have taken the place of empire; "the United States has pursued imperial policies, especially toward weak countries in the periphery. But U.S. relations with Europe, Japan, China, and Russia cannot be described as imperial... the use or threat of force is unthinkable. Their economies are deeply interwoven... they form a political order built on bargains, diffuse reciprocity, and an array of intergovernmental institutions and ad hoc working relationships. This is not empire; it is a U.S.-led democratic political order that has no name or historical antecedent." I.R. scholar Nye argues that US power is more and more based on "soft power," which comes from cultural hegemony rather than raw military or economic force. This includes such factors as the widespread desire to emigrate to the United States, the prestige and corresponding high proportion of foreign students at US universities, and the spread of US styles of popular music and cinema. Thus the US, no matter how hegemonic, is no longer an empire in the classic sense.

This point of view might be considered the mainstream or official interpretation of United States history within the US. The United States Information Agency writes that, "With the exception of the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, American territory had remained fixed since 1848. In the 1890s a new spirit of expansion took hold... Yet Americans, who had themselves thrown off the shackles of empire, were not comfortable with administering one. In 1902 American troops left Cuba... The Philippines obtained... complete independence in 1946. Puerto Rico became a self-governing commonwealth... and Hawaii became a state in 1959."

Temporary, but not an aberration

Some writers, such as critical international relations theorist James Der Derian and philosophers Jean Baudrillard and Antonio Negri, acknowledge most of the historical evils described by anti-imperialists, and see them as a consequence of a past US imperialism. But these authors argue that the United States is no longer imperialist, at least not in the classic sense, because the world has passed the era of imperialism and entered a new era. This new era still has oppressive, colonizing power, much of it rooted in the United States, but this colonizing power has moved from national military forces based on an economy of physical goods to networked biopower based on an informational, affective economy.

For Negri, writing with literary theorist Michael Hardt, the United States is central to the development and constitution of a new global regime of international power and sovereignty, termed "Empire." Their book builds on neomarxist, postcolonial, and postmodern ideas and globalization theories, rooting itself in the work of Foucault, Deleuze, and Italian autonomist marxists. Because the "Empire" of Hardt and Negri is decentralized and global, and not ruled by one sovereign state, it may be different from the "American Empire" described in this article; Hardt and Negri argue that "the United States does indeed occupy a privileged position in Empire, but this privilege derives not form its similarities to the old European imperialist powers, but from its differences."

Cultural imperialism

The debates about the issue of American cultural imperialism are largely separate from the debates about American military imperialism that are the subject of this article.

However, some critics of imperialism argue that cultural imperialism is not independent from military imperialism. Edward Said, one of the founders of the study of postcolonialism, claims that, "So influential has been the discourse insisting on American specialness, altruism and opportunity, that imperialism in the United States as a word or ideology has turned up only rarely and recently in accounts of the United States culture, politics and history. But the connection between imperial politics and culture in North America, and in particular in the United States, is astonishingly direct." He identifies the way non-Americans, particularly non-Westerns, are usually conceived of in the US as tacitly racist, in a way that allows imperialism to be justified through such ideas as the White Man's Burden.

Opponents of theories of cultural imperialism argue that it is not connected to any kind of military domination. International relations scholar David Rothkop claims that alleged cultural imperialism is the innocent result of globalization, which allows many consumers across the world who desire US products and ideas access to them. A worldwide fascination with the United States has not been forced on anyone in ways similar to what is traditionally described as an empire, differentiating it from the actions of the British Empire and other more easily identified empires throughout history. Rothkop identifies the desire to preserve the purity of one's culture as xenophobic.

Quotes

"...in Britain, empire was justified as a benevolent “white man’s burden.” And in the United States, empire does not even exist; “we” are merely protecting the causes of freedom, democracy, and justice worldwide."

Notes and references

- "American Empire". Western Washington University. Retrieved 2006-03-20."empire". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- "The domain ruled by an emperor or empress."

- "A political unit having an extensive territory or comprising a number of territories or nations and ruled by a single supreme authority."

- "Imperial or imperialistic sovereignty, domination, or control."

- Oxford English Dictionary (1989). "imperialism". Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- Oxford English Dictionary (1989). "empire". Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). "Benevolent Assimilation" The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300026978. p. 3.

- Thornton, Archibald Paton (September, 1978). Imperialism in the Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333248481.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 1.

- Miller (1982), op. cit. pp. 1-3.

- Edwords, Frederick (1987). "The religious character of American patriotism. It's time to recognize our traditions and answer some hard questions". The Humanist (p. 20-24, 36).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Kellner, Douglas (2003-04-25). "American Exceptionalism". Retrieved 2006-02-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Lens, Sidney (2003). The Forging of the American Empire. Haymarket Books and Pluto Press. ISBN 0745321003. Book jacket.

- Lens (2003), op. cit. Book jacket.

- Buchanan, Patrick (1999). A Republic, Not and Empire. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 089526272X. p. 165.

- Chomsky, Noam (1988). Manufacturing Consent. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0375714499 url=http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/Herman%20/Manufac_Consent_Prop_Model.html.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|id=(help) - Bacevich, Andrew (2004). American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674013751.

- Ali, Tariq (October 2001). "Tariq Ali on 9/11". Left Business Observer (98).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Churchill, Ward (2003). Reflections on the Justice of Roosting Chickens. AK Press. ISBN 1902593790.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Foster, John Bellamy (2003). "The New Age of Imperialism". Monthly Review.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bookman, Jay (June 25, 2003). "Let's just say it's not an empire". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Radosh, Ronald (February 7, 2003). "The Appeasers: Then and Now". New York Sun..

- Boot, Max (November 2003). "Neither New nor Nefarious: The Liberal Empire Strikes Back". Current History. 102 (667).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 220. See also Wikiquote: Philippine-American War Quotes.

- Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 136.

- Boot (2003), op. cit.

- Heer, Jeet (March 23, 2003). "Operation Anglosphere". Boston Globe.

- Ferguson, Niall (June 2, 2005). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. Penguin. ISBN 0141017007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 3.

- Lafeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-1898. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801490480.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (2002). "A Funny Sort of Empire". National Review.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ikenberry, G. John (March/April 2004). "Illusions of Empire: Defining the New American Order". Foreign Affairs.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ed. George Clack (September 1997). "A brief history of the United States". A Portrait of the USA. United States Information Agency. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Negri, Antonio (2000). id=ISBN 0674006712 Empire. Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) pp. xiii-xiv. - Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism, speech at York University, Toronto, February 10, 1993.

- Rothkop, David (June 22, 1997). "Globalization and Culture". Foreign Policy.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - (Author unknown) (2001). "After the Attack...The War on Terrorism". Monthly Review. 53 (6): p. 7.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

See also

- American Century

- Bush Doctrine

- Carter Doctrine

- Monroe Doctrine

- Truman Doctrine

- Neocolonialism

- Manifest Destiny

- Military history of the United States

- American foreign policy

- History of United States overseas expansion

- American exceptionalism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-imperialism

- List of U.S. foreign interventions since 1945

- Use of the word American

External links

- "America and Empire: Manifest Destiny Warmed Up?". The Economist.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) Argues that the U.S. is going through an imperial phase, but like previous phases, this will be temporary, since (they argue) empire is incompatible with traditional U.S. policies and beliefs. - "The American Empire Project". Retrieved 2006-06-10. A series of books from left-wing writers such as Noam Chomsky, critical of what they call the "American Empire".

- "An American Question". tygerland.net by AS Heath. Retrieved 2006-06-10.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) July 25, 2005 - Boot, Max (2003). "American imperialism? No need to run away from label". USA today.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Argues that "U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century." - Hitchens, Christopher, "Imperialism: Superpower dominance, malignant and benign". Slate.com. Retrieved 2006-06-10., warns that the U.S.—whether or not you call it an empire—should be careful to use its power wisely.

- Johnson, Paul, "America's New Empire for Liberty". Article from conservative writer and historian, argues that the U.S. has always been an empire—and a good one at that.

- Walzer, Michael, "Is There an American Empire?". www.freeindiamedia.com. Retrieved 2006-06-10. Argues that the term hegemony is better than the term empire to describe the US.

Further reading

- Perkins, John (2004). Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. ISBN 1576753018.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Zepezauer, Mark (2002). Boomerang! : How Our Covert Wars Have Created Enemies Across the Middle East and Brought Terror to America. ISBN 1567512224.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)