| Revision as of 17:55, 4 February 2014 view source41.96.7.179 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:55, 4 February 2014 view source Abce2 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers23,456 editsm Reverted edits by 41.96.7.179 (talk) to last version by PinethicketNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ]'']] |

]'']] | ||

| The '''Moors''' were the ] ] inhabitants of ], |

The '''Moors''' were the ] ] <ref>''The Story of the Moors in Spain(Illustrated)''. Stanley Lane-Poole, Arthur Gilman. Introduction by John G Jackson:"In ancient times, Africans in general were called Ethiopian; in medieval times most Africans were called Moors; in modern times some Africans were called Negroes."</ref> inhabitants of ], western ], ], ], the ], ], and ]. | ||

| ⚫ | The Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 and called the territory ], an area which at different times comprised ], most of ] and ], and parts of ]. There was also a Moorish presence in what is now Southern ], primarily in ]. They occupied ] on Sicily in 827<ref>{{Cite web |title=Assessment of the status, development and diversification of fisheries-dependent communities: Mazara del Vallo Case study report |url= http://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/documentation/studies/regional_social_economic_impacts/mazara_del_vallo_en.pdf |year= 2010 |publisher= ] |page = 2 |quote = ''In the year 827, Mazara was occupied by the Arabs, who made the city an important commercial harbor. That period was probably the most prosperous in the history of Mazara.'' |accessdate= 28 September 2012}}</ref> and in 1224 were expelled to the ], which was destroyed in 1300. The religious difference of the Moorish Muslims led to a centuries-long conflict with the ] called the ]. The ] in 1492 saw the end of the Muslim rule in Iberia. | ||

| ⚫ | The Moors |

||

| ]'s Ladies Tower]] | ]'s Ladies Tower]] | ||

| ] to join their alliance (contemporary depiction from ''The Cantigas de Santa Maria'')]] | ] to join their alliance (contemporary depiction from ''The Cantigas de Santa Maria'')]] | ||

| The term "Moors" has also been used in Europe in a broader sense to refer to Muslims,<ref name="Menocal, Maria Rosa 2002 page 241">Menocal, Maria Rosa (2002). "Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain". Little, Brown, & Co. ISBN 0-316-16871-8 page 241</ref> especially those of ] or ] descent, whether living in Spain or North Africa. During the colonial years the Dutch introduced the name "Moor", in Sri Lanka. The ] were called Moor.<ref>Pieris, P.E. "Ceylon and the Hollanders 1658-1796". American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai Ceylon 1918</ref> | |||

| The term "Moors" has also been used in Europe in a broader sense to refer to Muslims, especially those of ] or ] descent, whether living in Spain or North Africa. Moors are not a distinct or self-defined people. Medieval and early modern Europeans applied the name to the ], North African , ]<ref>,{{Dead link|date=September 2012}} ''Andalusia'', New York University. Quote: "Andalusi Arabic sources, as opposed to later ] and ] sources in Aljamiado and medieval Spanish texts, neither refer to individuals as Moors nor recognize any such group, community or culture."</ref> and West ] from ] and ] who had been absorbed into the ].<ref>, Volume 11{{Page needed|date=May 2012}}</ref> Scholars observed in 1911 that "The term 'Moors' has no real ] value."<ref>, ''Britannica Encyclopedia'' (1911), p. 811.</ref> | |||

| Moors are not a distinct or ] people.<ref>, ''Andalusia'', New York University. Quote: "Andalusi Arabic sources, as opposed to later ] and ] sources in Aljamiado and medieval Spanish texts, neither refer to individuals as Moors nor recognize any such group, community or culture."</ref> Medieval and early modern Europeans applied the name to the ], North African ]s, ], and ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=Imaging the Moor in Medieval Portugal|author=Josiah Blackmore|pages=27-43|journal=Diacritics|volume=36|number=3/4|date=Fall-Winter 2006|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/20204140|quote=] refers to the Sub-Sarahan Africans inhabiting these lands ]] alternately as ''negros'' (blacks), ''guinéus'' (Guineans), or ''mouros'' (Moors).}}</ref> | |||

| The Moors of ] of the ] after the ] in the early 8th century were initially |

The Moors came from the ] country of ] and crossed the ] to get into the Iberian Peninsula. The Moors of ] of the ] after the ] in the early 8th century were initially ] and ] but later came to include people of mixed heritage, and Iberian Christian converts to Islam, known by the Arabs as '']'' or ''Muladi''.<ref>Menocal, Maria Rosa (2002). "Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain" page 16 http://www.barnesandnoble.com/sample/read/9780316092791</ref><ref>Richard A Fletcher: Moorish Spain. University of California Press, 2006. page 1. http://books.google.com/books?id=wrMG-LfuU7oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Earlier, the ] interacted with (and later conquered) parts of ], a state that covered northern portions of modern Morocco and much of north western and central ] during the classical period. The people of the region were noted in ] as the '']''. Today such groups inhabit ] and parts of ], ], ], ] and ].<ref></ref> In the ], a number of associated ethnic groups have been historically designated as "Moors". In the modern Iberian Peninsula, "Moor" is sometimes colloquially applied to any person from North Africa, but some people consider this usage of the term ],<ref name="Menocal, Maria Rosa 2002 page 241"/> whether in the Spanish version "moro", or in the Portuguese version "mouro". | ||

| The maximum extent of ] rule stretched as far as modern-day ] and much of ], ], ] countries, and the ]. | |||

| ⚫ | Earlier, the ] interacted with (and later conquered) parts of ], a state that covered northern portions of modern |

||

| ==Name== | ==Name== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| ===Etymology=== | ===Etymology=== | ||

| {{further|Mauri people|Mauretania}} | {{further|Mauri people|Mauretania}} | ||

| ] of |

] of Morocco by the walls of Marrakesh, as painted by ], 1845]] | ||

| In ], the word ''Maurus'' (plural ''Mauri'') is in origin an ethnonym, the name of the ] who were also eponymous of the ] province of the Roman empire on the northwestern fringe of Africa. | In ], the word ''Maurus'' (plural ''Mauri'') is in origin an ethnonym, the name of the ] who were also eponymous of the ] province of the Roman empire on the northwestern fringe of Africa. The Latin form of the name is adapted from ], where the people were known as ''Mauroi'' (Μαῦροι). | ||

| The Latin form of the name is adapted from ], where the people was known ''Mauroi'' (Μαῦροι). | |||

| The Greek name has been speculatively connected to the adjective ἀμαυρός, meaning "dark; faint, dim".<ref> | The Greek name has been speculatively connected to the adjective ἀμαυρός, meaning "dark; faint, dim".<ref> | ||

| in either direction, i.e. the adjective (which appears only late) might be derived from the ethnonym, much like the later Romance terms for "dark-skinned"; ]: "perhaps a native name, or else cognate with ''mauros'' 'black' (but this adjective only appears in late Greek and may as well be from the people's name as the reverse)." | in either direction, i.e. the adjective (which appears only late) might be derived from the ethnonym, much like the later Romance terms for "dark-skinned"; ]: "perhaps a native name, or else cognate with ''mauros'' 'black' (but this adjective only appears in late Greek and may as well be from the people's name as the reverse)." | ||

| Line 30: | Line 29: | ||

| From denoting a specific Berber people in western ], the name acquired more general meaning in the Romance languages during the medieval period, partly developing a general meaning of "Muslim", partly (much like "]") taking a religious meaning of "infidels" in the context of the ] and the ]. | From denoting a specific Berber people in western ], the name acquired more general meaning in the Romance languages during the medieval period, partly developing a general meaning of "Muslim", partly (much like "]") taking a religious meaning of "infidels" in the context of the ] and the ]. | ||

| Beside its usage in historical context, ''Moor'' and ''Moorish'' (] and Spanish: ''moro'', ]: ''maure'', ]: ''mouro'', ]: ''maur'') is used to designate an ethnic group speaking the '']'' Arabic dialect. They inhabit ] and parts of ], ], ], ], ] and ]. In Niger and Mali, these peoples are also known as the ''Azawagh Arabs'', after the ] region of the Sahara.<ref>For an introduction to the culture of the ''Azawagh Arabs'', see: Rebecca Popenoe, ''Feeding Desire — Fatness, Beauty and Sexuality among a Saharan People''. Routledge, London (2003) ISBN 0-415-28096-6</ref> | Beside its usage in historical context, ''Moor'' and ''Moorish'' (] and Spanish: ''moro'', ]: ''maure'', ]: ''mouro'', ]: ''maur'') is used to designate an ethnic group speaking the '']'' Arabic dialect. They inhabit ] and parts of ], ], ], ], ] and ]. In Niger and Mali, these peoples are also known as the ''Azawagh Arabs'', after the ] region of the Sahara.<ref>For an introduction to the culture of the ''Azawagh Arabs'', see: Rebecca Popenoe, ''Feeding Desire — Fatness, Beauty and Sexuality among a Saharan People''. Routledge, London (2003) ISBN 0-415-28096-6</ref> | ||

| In Spain, modern colloquial Spanish use of the term "Moro" is derogatory for ]in particular<ref>{{cite book|last=Simms|first=Karl|title=Translating sensitive texts: linguistic aspects|year=1997|publisher=Rodopi|isbn=978-90-420-0260-9|pages=144|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=t4y7EHgCn8kC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Warwick Armstrong|first=James Anderson|title=Geopolitics of European Union enlargement: the fortress empire|year=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-33939-1|pages=83|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=0pmkrY29qkIC&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Wessendorf|first=Susanne|title=The multiculturalism backlash: European discourses, policies and practices|year=2010|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-415-55649-1|pages=171|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wUaHVimJkT0C&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou|first=Ricard Zapata-Barrero|title=Multiculturalism, Muslims and citizenship: a European approach|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-35515-5|pages=143|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7OAAV5eEmy4C&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Bekers|first=Elisabeth|title=Transcultural modernities: narrating Africa in Europe|year=2009|publisher=Rodopi|isbn=978-90-420-2538-7|pages=14|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=N4_on188WJwC&dq}}</ref> and ]s in general. | In Spain, modern colloquial Spanish use of the term "Moro" is derogatory for ] in particular<ref>{{cite book|last=Simms|first=Karl|title=Translating sensitive texts: linguistic aspects|year=1997|publisher=Rodopi|isbn=978-90-420-0260-9|pages=144|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=t4y7EHgCn8kC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Warwick Armstrong|first=James Anderson|title=Geopolitics of European Union enlargement: the fortress empire|year=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-33939-1|pages=83|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=0pmkrY29qkIC&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Wessendorf|first=Susanne|title=The multiculturalism backlash: European discourses, policies and practices|year=2010|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-415-55649-1|pages=171|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wUaHVimJkT0C&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou|first=Ricard Zapata-Barrero|title=Multiculturalism, Muslims and citizenship: a European approach|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-35515-5|pages=143|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7OAAV5eEmy4C&dq}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Bekers|first=Elisabeth|title=Transcultural modernities: narrating Africa in Europe|year=2009|publisher=Rodopi|isbn=978-90-420-2538-7|pages=14|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=N4_on188WJwC&dq}}</ref> and ]s in general. | ||

| Similarly, in modern, colloquial ], the term "Mouro" was primarily used as a designation for North Africans and secondarily as a derogatory and ironic term by northern ] to refer to the inhabitants of the southern parts of the country (], ] and ]). However, this designation has gained more acceptance in the South. | Similarly, in modern, colloquial ], the term "Mouro" was primarily used as a designation for North Africans and secondarily as a derogatory and ironic term by northern ] to refer to the inhabitants of the southern parts of the country (], ] and ]). However, this designation has gained more acceptance in the South. | ||

| In the ], a former ], many residents call the local Muslim population in the Southern islands ''Moros''. They also self-identify that way (see ]). The term was introduced by the Spanish colonizers. Within the context of ], in ] (]), Muslims of |

In the ], a former ], many residents call the local Muslim population in the Southern islands ''Moros''. They also self-identify that way (see ]). The term was introduced by the Spanish colonizers. Within the context of ], in ] (]), Muslims of Arab origin are called ''Moors'' (see ]). | ||

| ]'' (Moors and Christians) in Mexico]] | ]'' (Moors and Christians) in Mexico]] | ||

| '']'' can mean ''dark-skinned'' in Spain and Portugal, as well as in Brazil. Also in Spanish, ''morapio'' is a humorous name for "wine", especially that which has not been "baptized" or mixed with water, i.e., pure unadulterated wine. Among Spanish speakers, ''moro'' ("Moor") came to have a broader meaning, applied to both ]s of ] in the ], and the ]s of ]. ''Moro'' is refers to all things dark, as in "Moor", ''moreno'', etc. It was used as a nickname; for instance, the ]ese Duke ] was called ''Il Moro'' because of his dark complexion. |

'']'' can mean ''dark-skinned'' in Spain and Portugal, as well as in Brazil. Also in Spanish, ''morapio'' is a humorous name for "wine", especially that which has not been "baptized" or mixed with water, i.e., pure unadulterated wine. Among Spanish speakers, ''moro'' ("Moor") came to have a broader meaning, applied to both ]s of ] in the ], and the ]s of ]. ''Moro'' is refers to all things dark, as in "Moor", ''moreno'', etc. It was used as a nickname; for instance, the ]ese Duke ] was called ''Il Moro'' because of his dark complexion. | ||

| In Portugal and Spain, ''mouro'' (feminine,'' moura'') may also refer to supernatural beings known as ], where "moor" implies 'alien' and 'non-Christian'; These beings were siren-like fairies with golden or reddish hair and a fair face. They were believed to have magical properties.<ref>, Galicia: Editorial Galaxia, 2004, p. 18, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010 {{es icon}}</ref> From this root, the name moor is also applied to unbaptized children, meaning not ].<ref>, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 1936; reprint CUP Archives, 1961, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010.</ref><ref>, in ''Revista de Guimaraes'', No. 100, 1990, Centro de Estudos de Património, Universidade do Minho, accessed 12 Jul 2010 {{pt icon}}</ref> In ], '']'' means moor and also refers to a mythical people.<ref> {{es icon}}</ref>{{Dead link|date=July 2010}} | In Portugal and Spain, ''mouro'' (feminine,'' moura'') may also refer to supernatural beings known as ], where "moor" implies 'alien' and 'non-Christian'; These beings were siren-like fairies with golden or reddish hair and a fair face. They were believed to have magical properties.<ref>, Galicia: Editorial Galaxia, 2004, p. 18, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010 {{es icon}}</ref> From this root, the name moor is also applied to unbaptized children, meaning not ].<ref>, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 1936; reprint CUP Archives, 1961, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010.</ref><ref>, in ''Revista de Guimaraes'', No. 100, 1990, Centro de Estudos de Património, Universidade do Minho, accessed 12 Jul 2010 {{pt icon}}</ref> In ], '']'' means moor and also refers to a mythical people.<ref> {{es icon}}</ref>{{Dead link|date=July 2010}} | ||

| Moors is also a term used to identify ]. ] are 12% of the population |

Moors is also a term used to identify ]. ] are 12% of the population. The Moors in Sri Lanka are descendants of Arab traders who settled in Sri Lanka in the mid-6th century. When the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, they labelled the Muslims in the island as Moors as they saw them resembling the Moors in North Africa. The Sri Lankan government to this day identifies the Muslims in Sri Lanka as "Ceylon Moors"<ref>A. Hussein 'From where did the moors come from?', http://www.lankalibrary.com/cul/muslims/moors.htm {{verify credibility|date=January 2013}}</ref> | ||

| When the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, they labelled the Muslims in the island as Moors as they saw them resembling the Moors in North Africa. The Sri Lankan government to this day identifies the Muslims in Sri Lanka as "Ceylon Moors"<ref>A. Hussein 'From where did the moors come from?', http://www.lankalibrary.com/cul/muslims/moors.htm {{verify credibility|date=January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| The ] - a minority community who follow ] in the western ]n coastal state of ] are commonly referred as ''Moir'' ({{lang-knn|मैर}}) by ] and ]s.{{Ref label|a|a|none}}. |

The ] - a minority community who follow ] in the western ]n coastal state of ] are commonly referred as ''Moir'' ({{lang-knn|मैर}}) by ] and ]s.{{Ref label|a|a|none}}. ''Moir'' is derived from the ] word ''mouro'' (Moors). | ||

| ==Moors of Iberia== | ==Moors of Iberia== | ||

| {{Further|Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Al-Andalus}} | {{Further|Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Al-Andalus}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] (790–1300)]] | ] (790–1300)]] | ||

| In 711 ], the now Islamic Moors conquered ] ] ]. Their ], ], brought most of Iberia under Islamic rule in an eight-year campaign. They moved northeast across the ] Mountains, but were defeated by the ] ] at the ] in 732. | In 711 ], the now Islamic Moors came from the ]n country ] and crossed the ] to get into the ] and in a series of raids conquered ] ] ].<ref>Richard A Fletcher: Moorish Spain. 1992. page 1. http://books.google.com/books?id=wrMG-LfuU7oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false</ref> Their ], ], brought most of Iberia under Islamic rule in an eight-year campaign. They moved northeast across the ] Mountains, but were defeated by the ] ] at the ] in 732. | ||

| ], ], Spain. Depicting severed heads of the Moors]] | ], ], Spain. Depicting severed heads of the Moors]] | ||

| The Moorish state fell into ] in the 750s. The Moors ruled in North Africa and in most of the ] for several decades. |

The Moorish state fell into ] in the 750s. The Moors ruled in North Africa and in most of the ] for several decades. They were resisted in areas in the northwest (such as ], where they were defeated at the battle of ]) and the largely ] in the Pyrenees. Though the number of Moor colonists was small, many ]. According to Ronald Segal, by 1000, some 5 million of Iberia's 7 million inhabitants, most of them descended from indigenous Iberian converts, were Muslim. There were also West ] from ] and ] who had been absorbed into the ], which was a ] dynasty and a part of the Iberian Peninsula during ].<ref>{{cite book|author=Ivan Van Sertima|title=The Golden Age of the Moor|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=1F9HPuDkySsC&pg=PA175|year=1992|publisher=Transaction Publishers|isbn=978-1-4128-1536-9|page=175}}</ref>{{Better source|reason=Ivan Van Seritima is not incorrect on this point, but he is known for Pseudohistory, a better source is needed|date=December 2013}}<ref>Ronald Segal, ''Islam's Black Slaves'' (2003), Atlantic Books, ISBN 1-903809-81-9</ref> | ||

| In a process of decline, the Al Andalus had broken up into a number of Islamic-ruled ], or '']'', which were partly consolidated under the ]. |

In a process of decline, the Al Andalus had broken up into a number of Islamic-ruled ], or '']'', which were partly consolidated under the ]. | ||

| ] during the ], from ''Cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio'']] | ] during the ], from ''Cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio'']] | ||

| The ], a small northwestern Christian Iberian kingdom, initiated the Reconquista (the "reconquest") soon after the Islamic conquest in the 8th century. Christian states based in the north and west slowly extended their power over the rest of Iberia. ], ], ], ], ], '']'', and ] began a process of expansion and internal consolidation during the next several centuries under the flag of ]. | The ], a small northwestern Christian Iberian kingdom, initiated the Reconquista (the "reconquest") soon after the Islamic conquest in the 8th century. Christian states based in the north and west slowly extended their power over the rest of Iberia. ], ], ], ], ], '']'', and ] began a process of expansion and internal consolidation during the next several centuries under the flag of ]. | ||

| ] from a German book published in 1880]] | ] from a German book published in 1880]] | ||

| In 1212, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of ] drove the Muslims from Central Iberia. The Portuguese side of the ''Reconquista'' ended in 1249 with the conquest of the ] (] الغرب |

In 1212, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of ] drove the Muslims from Central Iberia. The Portuguese side of the ''Reconquista'' ended in 1249 with the conquest of the ] (] الغرب – '']'') under ]. He was the first Portuguese monarch to claim the title "]". | ||

| The Moorish ] continued for three more centuries in southern Iberia. On January 2, 1492, the leader of the last Muslim stronghold in ] surrendered to armies of a recently united Christian Spain (after the marriage of ] and ], the ]). They forced the remaining Jews to leave Spain, convert to Roman Catholic Christianity or be killed for not doing so. To exert social and religious control, in 1480, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to allow the ]. Granada's Muslim population ]. The revolt lasted until early 1501, giving the Castilian authorities an excuse to void the terms of the ] (1491). In 1501 Castilian authorities delivered an ultimatum to Granada's Muslims: they could either convert to Christianity or be expelled. |

The Moorish ] continued for three more centuries in southern Iberia. On January 2, 1492, the leader of the last Muslim stronghold in ] surrendered to armies of a recently united Christian Spain (after the marriage of ] and ], the ]). They forced the remaining Jews to leave Spain, convert to Roman Catholic Christianity or be killed for not doing so. To exert social and religious control, in 1480, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to allow the ]. Granada's Muslim population ]. The revolt lasted until early 1501, giving the Castilian authorities an excuse to void the terms of the ] (1491). In 1501 Castilian authorities delivered an ultimatum to Granada's Muslims: they could either convert to Christianity or be expelled. | ||

| The Inquisition was aimed mostly at Jews and Muslims who had overtly converted to Christianity but were thought to be practicing their faiths secretly. They were respectively called '']s'' and '']s''. However, in 1567 King ] directed Moriscos to give up their Arabic names and traditional dress, and prohibited the use of the ] language. In reaction, there was a ] in the ] from 1568 to 1571. In the years from 1609 to 1614, the government expelled Moriscos. The historian Henri Lapeyre estimated that this affected 300,000 out of an estimated total of 8 million inhabitants.<ref>See ''History of ]''.</ref> | The Inquisition was aimed mostly at Jews and Muslims who had overtly converted to Christianity but were thought to be practicing their faiths secretly. They were respectively called '']s'' and '']s''. However, in 1567 King ] directed Moriscos to give up their Arabic names and traditional dress, and prohibited the use of the ] language. In reaction, there was a ] in the ] from 1568 to 1571. In the years from 1609 to 1614, the government expelled Moriscos. The historian Henri Lapeyre estimated that this affected 300,000 out of an estimated total of 8 million inhabitants.<ref>See ''History of ]''.</ref> | ||

| ]'' of ], c. 1285]] | ]'' of ], c. 1285]] | ||

| Many Muslims converted to Christianity and remained permanently in Iberia. This is indicated by a "high mean proportion of ancestry from North African (10.6%)" that "attests to a high level of religious conversion (whether voluntary or enforced), driven by historical episodes of social and religious intolerance, that ultimately led to the integration of descendants." |

Many Muslims converted to Christianity and remained permanently in Iberia. This is indicated by a "high mean proportion of ancestry from North African (10.6%)" that "attests to a high level of religious conversion (whether voluntary or enforced), driven by historical episodes of social and religious intolerance, that ultimately led to the integration of descendants."<ref>, ''Cell'', 2008. Quote: "Admixture analysis based on binary and Y-STR haplotypes indicates a high mean proportion of ancestry from North African (10.6%) ranging from zero in Gascony to 21.7% in Northwest Castile."</ref><ref>, University of , 2008, Quote: "The study shows that religious conversions and the subsequent marriages between people of different lineage had a relevant impact on modern populations both in Spain, especially in the Balearic Islands, and in Portugal."</ref> | ||

| In the meantime, the tide of Islam had rolled not just to Iberia, but also eastward, through India, the ], and ] up to the ]. This was one of the major islands of an ] which the Spaniards had reached during their voyages westward from the ]. By 1521, the ships of ]{{Citation needed|date=May 2012}} and other Spanish explorers had reached that island archipelago, which they named '']'', after ]. In Mindanao, the Spaniards named the ]-bearing people as ] or 'Moors'. Today in the Philippines, this ethnic group of people in Mindanao, who are generally ], are called 'Moros'. This identification of Islamic people as ''Moros'' persists in the modern ] spoken in Spain, and as ''Mouros'' in the modern ]. See ], and ]. | In the meantime, the tide of Islam had rolled not just to Iberia, but also eastward, through India, the ], and ] up to the ]. This was one of the major islands of an ] which the Spaniards had reached during their voyages westward from the ]. By 1521, the ships of ]{{Citation needed|date=May 2012}} and other Spanish explorers had reached that island archipelago, which they named '']'', after ]. In Mindanao, the Spaniards named the ]-bearing people as ] or 'Moors'. Today in the Philippines, this ethnic group of people in Mindanao, who are generally ], are called 'Moros'. This identification of Islamic people as ''Moros'' persists in the modern ] spoken in Spain, and as ''Mouros'' in the modern ]. See ], and ]. | ||

| According to historian ],<ref>Richard Fletcher. ''Moorish Spain'' p. 10. University of California Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-520-08496-4</ref> |

According to historian ],<ref>Richard Fletcher. ''Moorish Spain'' p. 10. University of California Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-520-08496-4</ref> "the number of ]s who settled in Iberia was very small. 'Moorish' Iberia does at least have the merit of reminding us that the bulk of the invaders and settlers were Moors, i.e., ] from Algeria and Morocco." | ||

| The initial rule of the Moors in the Iberian peninsula under this ] is regarded as tolerant in its acceptance of Christians, Muslims and ]s living in the same territories.{{Citation needed|date=September 2011}} The Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed in 1031 and the Islamic territory in Iberia fell under the rule of the ] in 1153. This second stage inaugurated an era of Moorish rulers guided by a version of Islam that left behind the tolerant practices of the past.<ref> by Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, '']''. 1906 ed.</ref> | The initial rule of the Moors in the Iberian peninsula under this ] is regarded as tolerant in its acceptance of Christians, Muslims and ]s living in the same territories.{{Citation needed|date=September 2011}} The Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed in 1031 and the Islamic territory in Iberia fell under the rule of the ] in 1153. This second stage inaugurated an era of Moorish rulers guided by a version of Islam that left behind the tolerant practices of the past.<ref> by Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, '']''. 1906 ed.</ref> | ||

| <gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| File:Othellopainting.jpg|] and ], his ] wife, from ]'s play '']'' | |||

| File:Batalla del Puig por Marzal de Sas (1410-20).jpg|"]" (c. 1410-1420), depicting a battle from the Reconquista | File:Batalla del Puig por Marzal de Sas (1410-20).jpg|"]" (c. 1410-1420), depicting a battle from the Reconquista | ||

| File:Tariq-ibn-Ziyad---w.jpg|] was the Moor general who led the conquest of ] in the early 8th century | |||

| File:Moor Painting.jpg|Moors playing chess, from ''Comentarios de la cosas de Aragon'' | |||

| File:Moors_from_Andalusia_playing_chess.jpg|Moors in Spain playing chess, from the '']'' | |||

| File:Jaume I, Cantigas de Santa Maria, s.XIII.jpg|The Moors request permission from ] | File:Jaume I, Cantigas de Santa Maria, s.XIII.jpg|The Moors request permission from ] | ||

| File:Wild Men and Moors (Detail 11 of 12).jpg|"Wild Men and Moors" tapestry, c. 1400 | File:Wild Men and Moors (Detail 11 of 12).jpg|"Wild Men and Moors" tapestry, c. 1400 | ||

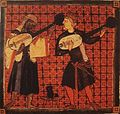

| File:Christian and Muslim playing ouds Catinas de Santa Maria by king Alfonso X.jpg|Christian and Moor playing ]s, 13th century | File:Christian and Muslim playing ouds Catinas de Santa Maria by king Alfonso X.jpg|Christian and Moor playing ]s, 13th century | ||

| File:Maler der Geschichte von Bayâd und Riyâd 003.jpg|Riyad the Moor receiving a letter from Shanul in ] | |||

| File:El rey chico de Granada.jpg|], last |

File:El rey chico de Granada.jpg|], last Muslim sultan in Spain | ||

| File:Leo africanus.jpg|], born in Granada | File:Leo africanus.jpg|], born in Granada | ||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| ==Moors of Sicily== | ==Moors of Sicily== | ||

| {{See also|History of Islam in southern Italy|Arab-Norman culture}} | {{See also|History of Islam in southern Italy|left|Arab-Norman culture}} | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| The first Muslim conquest of Sicily and parts of southern Italy lasted 75 years (827–902). By 827, Sicily was almost entirely in control of the ] with the exception of some minor strongholds in the rugged interior until 909 when it was then replaced by Shiite Fatimids. Four years later, the Fatimid governor was ousted from Palermo when the island declared its independence under Emir Ahmed ibn-Kohrob. |

The first Muslim conquest of Sicily and parts of southern Italy lasted 75 years (827–902). By 827, Sicily was almost entirely in control of the ] with the exception of some minor strongholds in the rugged interior until 909 when it was then replaced by Shiite Fatimids. Four years later, the Fatimid governor was ousted from Palermo when the island declared its independence under Emir Ahmed ibn-Kohrob. | ||

| In 1038, a Byzantine army under George Maniaces crossed the strait of Messina. This included a corps of Normans which saved the situation in the first clash against the Muslims from Messina. After another decisive victory in the summer of 1040, Maniaces halted his march to lay siege to ]. Despite his conquest of the latter, Maniaces was removed from his position, and the subsequent Muslim counter-offensive reconquered all the cities captured by the Byzantines. | In 1038, a Byzantine army under George Maniaces crossed the strait of Messina. This included a corps of Normans which saved the situation in the first clash against the Muslims from Messina. After another decisive victory in the summer of 1040, Maniaces halted his march to lay siege to ]. Despite his conquest of the latter, Maniaces was removed from his position, and the subsequent Muslim counter-offensive reconquered all the cities captured by the Byzantines. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

| The Norman ], son of Tancred, invaded Sicily in 1060. The island was split between three Arab emirs, and the Christian population in many parts of the island rose up against the ruling Muslims. One year later, Messina fell, and in 1072, Palermo was taken by the Normans. The loss of the cities, each with a splendid harbor, dealt a severe blow to Muslim power on the island. Eventually all of Sicily was taken. In 1091, Noto in the southern tip of Sicily and the island of Malta, the last Arab strongholds, fell to the Christians. | The Norman ], son of Tancred, invaded Sicily in 1060. The island was split between three Arab emirs, and the Christian population in many parts of the island rose up against the ruling Muslims. One year later, Messina fell, and in 1072, Palermo was taken by the Normans. The loss of the cities, each with a splendid harbor, dealt a severe blow to Muslim power on the island. Eventually all of Sicily was taken. In 1091, Noto in the southern tip of Sicily and the island of Malta, the last Arab strongholds, fell to the Christians. | ||

| Islamic authors would marvel at the tolerance of the ] kings of Sicily. ] wrote: "They were treated kindly, and they were protected, even against the ]. Because of that, they had great love for king Roger."<ref>{{cite book|last=Aubé|first=Pierre|title=Les empires normands d’Orient|year=2006|publisher= Editions Perrin|page=168|isbn=2-262-02297-6}}</ref> |

Islamic authors would marvel at the tolerance of the ] kings of Sicily. ] wrote: "They were treated kindly, and they were protected, even against the ]. Because of that, they had great love for king Roger."<ref>{{cite book|last=Aubé|first=Pierre|title=Les empires normands d’Orient|year=2006|publisher= Editions Perrin|page=168|isbn=2-262-02297-6}}</ref> | ||

| Many repressive measures were introduced by ] to please the popes who were intolerant of Islam in the heart of Christendom. This resulted in a rebellion by Sicilian Muslims, which in turn triggered organized resistance and systematic reprisals and marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The Muslim problem characterized Hohenstaufen rule in Sicily under Henry VI and his son Frederick II. The complete eviction of Muslims and the annihilation of Islam in Sicily was completed by the late 1240s when the final deportations to ] took place. | Many repressive measures were introduced by ] to please the popes who were intolerant of Islam in the heart of Christendom. This resulted in a rebellion by Sicilian Muslims, which in turn triggered organized resistance and systematic reprisals and marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The Muslim problem characterized Hohenstaufen rule in Sicily under Henry VI and his son Frederick II. The complete eviction of Muslims and the annihilation of Islam in Sicily was completed by the late 1240s when the final deportations to ] took place. | ||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

| == Architecture == | == Architecture == | ||

| {{Main|Moorish architecture}} | {{Main|Moorish architecture}} | ||

| ], ]]] | ], ]]] | ||

| Moorish architecture is the ] ] of North Africa and parts of Spain and Portugal where the Moors were dominant between 711 and 1492. The best surviving examples are La ] in ] and the ] palace (mainly 1338–1390),<ref name="curl">Curl p. 502.</ref> and also the ] in 1184.<ref name="Pev">Pevsner, ''The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture''.</ref> Other notable examples include the ruined palace city of ] (936–1010), the church (former mosque) San Cristo de la Luz in ], the ] in ] and baths at for example ] and ]. | Moorish architecture is the ] ] of North Africa and parts of Spain and Portugal where the Moors were dominant between 711 and 1492. The best surviving examples are La ] in ] and the ] palace (mainly 1338–1390),<ref name="curl">Curl p. 502.</ref> and also the ] in 1184.<ref name="Pev">Pevsner, ''The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture''.</ref> Other notable examples include the ruined palace city of ] (936–1010), the church (former mosque) San Cristo de la Luz in ], the ] in ] and baths at for example ] and ]. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

| ==Moors in heraldry== | ==Moors in heraldry== | ||

| {{main|Maure}} | |||

| ](d.1474), as depicted on his canopied tomb in ] Church, showing the ''couped'' heads of three Moors wreathed at the temples]] | ](d.1474), as depicted on his canopied tomb in ] Church, showing the ''couped'' heads of three Moors wreathed at the temples]] | ||

| Moors—or more frequently their heads, often crowned—appear with some frequency in medieval European ]. The term ascribed to them in ] '']'' (the language of English heraldry) is ''maure'', though they are also sometimes called ''moore'', ''blackmoor'', ''blackamoor'' or ''negro''.<ref>{{cite web | title=Man | work= A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry | last=Parker | first=James | url=http://www.heraldsnet.org/saitou/parker/Jpglossm.htm#Man | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> ]s appear in European heraldry from at least as early as the 13th century,<ref name=VAM>{{cite web | title=Africans in medieval & Renaissance art: the Moor's head | url=http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/africans-in-medieval-and-renaissance-art-moors-head/ | publisher=Victoria and Albert Museum | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> and some have been attested as early as the 11th century in ],<ref name=VAM /> where they have persisted in the local heraldry and ] well into modern times in ] and ]. | Moors—or more frequently their heads, often crowned—appear with some frequency in medieval European ]. The term ascribed to them in ] '']'' (the language of English heraldry) is ''maure'', though they are also sometimes called ''moore'', ''blackmoor'', ''blackamoor'' or ''negro''.<ref>{{cite web | title=Man | work= A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry | last=Parker | first=James | url=http://www.heraldsnet.org/saitou/parker/Jpglossm.htm#Man | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> ]s appear in European heraldry from at least as early as the 13th century,<ref name=VAM>{{cite web | title=Africans in medieval & Renaissance art: the Moor's head | url=http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/africans-in-medieval-and-renaissance-art-moors-head/ | publisher=Victoria and Albert Museum | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> and some have been attested as early as the 11th century in ],<ref name=VAM /> where they have persisted in the local heraldry and ] well into modern times in ] and ]. | ||

| Armigers bearing moors or moors' heads may have adopted them for any of several reasons, to include symbolizing military victories in the ], as a pun on the bearer's name in the ] of Morese, Negri, Saraceni, etc., or in the case of ], possibly to demonstrate the reach of his empire.<ref name=VAM /> |

Armigers bearing moors or moors' heads may have adopted them for any of several reasons, to include symbolizing military victories in the ], as a pun on the bearer's name in the ] of Morese, Negri, Saraceni, etc., or in the case of ], possibly to demonstrate the reach of his empire.<ref name=VAM /> The ] feature a moor's head, crowned and collared red, in reference to the arms of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/elezione/stemma-benedict-xvi_en.html |author=Mons. Andrea Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo |title=Coat of Arms of His Holiness Benedict XVI |publisher=The Holy See |accessdate=2013-01-25}}</ref> In the case of Corsica and Sardinia, the blindfolded moors' heads in the four quarters have long been said to represent the four Moorish emirs who were defeated by ] in the 11th century, the four moors' heads around a cross having been adopted to the arms of Aragon around 1281–1387, and Corsica and Sardinia having come under the dominion of the king of Aragon in 1297.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/fr-co.html |last=Sache |first=Ivan |date=2009-06-14 |title=Corsica (France, Traditional province) |publisher=Flags of the World |accessdate=2013-01-25}}</ref> In Corsica, the blindfolds were lifted to the brow in the 18th century as a way of expressing the island's newfound independence <ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vaguelyinteresting.co.uk/?tag=flag-of-sardinia |last=Curry |first=Ian |date=2012-03-18 |title=Blindfolded Moors - The Flags of Corsica and Sardinia |publisher=Vaguely Interesting |accessdate=2013-01-25}}</ref> | ||

| The use of moors (and particularly their heads) as a heraldic symbol has been deprecated in modern North America,<ref>In his July 15, 2005 blog article , Mathew N. Schmalz refers to a discussion on the ]'s website where at least one participant described the moor's head as a "potentially explosive image".</ref> where racial stereotypes have been influenced by a history of ] and racial segregation, and applicants to the College of Arms of the ] are urged to use them delicately to avoid creating offensive images.<ref>{{cite web | title=Part IX: Offensive Armory | work=Rules for Submissions of the College of Arms of the Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. | url=http://heraldry.sca.org/laurel/rfs.html#9 | date=2008-04-02 | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> | The use of moors (and particularly their heads) as a heraldic symbol has been deprecated in modern North America,<ref>In his July 15, 2005 blog article , Mathew N. Schmalz refers to a discussion on the ]'s website where at least one participant described the moor's head as a "potentially explosive image".</ref> where racial stereotypes have been influenced by a history of ] and racial segregation, and applicants to the College of Arms of the ] are urged to use them delicately to avoid creating offensive images.<ref>{{cite web | title=Part IX: Offensive Armory | work=Rules for Submissions of the College of Arms of the Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. | url=http://heraldry.sca.org/laurel/rfs.html#9 | date=2008-04-02 | accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> | ||

| Line 115: | Line 116: | ||

| ==Population== | ==Population== | ||

| Populations in Carthage circa 200 BC and northern Algeria 1500 BC were diverse.{{Citation |

Populations in Carthage circa 200 BC and northern Algeria 1500 BC were diverse.{{Citation needed|date=July 2013}} As a group, they plotted closest to the populations of Northern Egypt and intermediate to Northern Europeans and tropical Africans: "the data supported the comments from ancient authors observed by classicists: everything from fair-skinned blonds to peoples who were dark-skinned 'Ethiopian' or part Ethiopian in appearance."<ref>G. Mokhtar. ''General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa'', p. 427.</ref> Modern evidence shows a similar diversity among present North Africans. Moreover, this diversity of phenotypes and peoples was probably due to '']'' differentiation, not foreign influxes.{{Citation needed|date=July 2013}} Foreign influxes are thought to have had an impact on population make-up, but did not replace the indigenous Berber population.<ref>"Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa", ''American Journal of Physical Anthropology'', 83:35-48 (1990).</ref> | ||

| == Notable Moors == | == Notable Moors == | ||

| Line 202: | Line 203: | ||

| * Stanley Lane-Poole, ''The History of the Moors in Spain''. | * Stanley Lane-Poole, ''The History of the Moors in Spain''. | ||

| * J. A. (Joel Augustus) Rogers. ''Nature Knows No Color Line: research into the Negro ancestry in the white race''. New York: 1952. | * J. A. (Joel Augustus) Rogers. ''Nature Knows No Color Line: research into the Negro ancestry in the white race''. New York: 1952. | ||

| * Ronald Segal. ''Islam's Black Slaves: the other Black diaspora. NY: Farrar |

* Ronald Segal. ''Islam's Black Slaves: the other Black diaspora. NY: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001. | ||

| * Ivan Van Sertima, ed. The Golden Age of the Moor. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1992. (Journal of African civilizations, vol. 11). | * Ivan Van Sertima, ed. The Golden Age of the Moor. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1992. (Journal of African civilizations, vol. 11). | ||

| * Frank Snowden. Before Color Prejudice: the ancient view of blacks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1983. | * Frank Snowden. Before Color Prejudice: the ancient view of blacks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1983. | ||

| Line 217: | Line 218: | ||

| * (2006) | * (2006) | ||

| * , Classic Encyclopedia (1911) | * , Classic Encyclopedia (1911) | ||

| * . Paper presented at an International Conference Organized by The Postgraduate School of Critical Theory and Cultural Studies, University of Nottingham, and The British Council, |

* . Paper presented at an International Conference Organized by The Postgraduate School of Critical Theory and Cultural Studies, University of Nottingham, and The British Council, Morocco, 12–14 April 2001. | ||

| * , ] (n.d) | * , ] (n.d) | ||

| * Sean Cavazos-Kottke. : (outline). ], 1998. | * Sean Cavazos-Kottke. : (outline). ], 1998. | ||

Revision as of 17:55, 4 February 2014

The Moors were the medieval Muslim inhabitants of Morocco, western Algeria, Western Sahara, Mauritania, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta.

The Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 and called the territory Al-Andalus, an area which at different times comprised Gibraltar, most of Spain and Portugal, and parts of France. There was also a Moorish presence in what is now Southern Italy, primarily in Sicily. They occupied Mazara on Sicily in 827 and in 1224 were expelled to the settlement of Lucera, which was destroyed in 1300. The religious difference of the Moorish Muslims led to a centuries-long conflict with the Christian kingdoms of Europe called the Reconquista. The Fall of Granada in 1492 saw the end of the Muslim rule in Iberia.

The term "Moors" has also been used in Europe in a broader sense to refer to Muslims, especially those of Arab or African descent, whether living in Spain or North Africa. During the colonial years the Dutch introduced the name "Moor", in Sri Lanka. The Bengali Muslims were called Moor. Moors are not a distinct or self-defined people. Medieval and early modern Europeans applied the name to the Berbers, North African Arabs, Muslim Iberians, and Sub-Saharan Africans.

The Moors came from the North African country of Morocco and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to get into the Iberian Peninsula. The Moors of Al-Andalus of the late Medieval after the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the early 8th century were initially Arabs and Berbers but later came to include people of mixed heritage, and Iberian Christian converts to Islam, known by the Arabs as Muwalladun or Muladi.

Earlier, the Classical Romans interacted with (and later conquered) parts of Mauretania, a state that covered northern portions of modern Morocco and much of north western and central Algeria during the classical period. The people of the region were noted in Classical literature as the Mauri. Today such groups inhabit Mauritania and parts of Algeria, Western Sahara, Morocco, Niger and Mali. In the languages of Europe, a number of associated ethnic groups have been historically designated as "Moors". In the modern Iberian Peninsula, "Moor" is sometimes colloquially applied to any person from North Africa, but some people consider this usage of the term pejorative, whether in the Spanish version "moro", or in the Portuguese version "mouro".

Name

Etymology

Further information: Mauri people and Mauretania

In Latin, the word Maurus (plural Mauri) is in origin an ethnonym, the name of the Mauri people who were also eponymous of the Mauretania province of the Roman empire on the northwestern fringe of Africa. The Latin form of the name is adapted from Greek ethnography, where the people were known as Mauroi (Μαῦροι). The Greek name has been speculatively connected to the adjective ἀμαυρός, meaning "dark; faint, dim".

Modern meanings

In the Medieval Romance languages (such as Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Romanian), the Latin word took such forms as mouro, moro, moir, mor and maur. From denoting a specific Berber people in western Libya, the name acquired more general meaning in the Romance languages during the medieval period, partly developing a general meaning of "Muslim", partly (much like "Saracens") taking a religious meaning of "infidels" in the context of the Crusades and the Reconquista.

Beside its usage in historical context, Moor and Moorish (Italian and Spanish: moro, French: maure, Portuguese: mouro, Romanian: maur) is used to designate an ethnic group speaking the Hassaniya Arabic dialect. They inhabit Mauritania and parts of Algeria, Western Sahara, Tunisia, Morocco, Niger and Mali. In Niger and Mali, these peoples are also known as the Azawagh Arabs, after the Azawagh region of the Sahara.

In Spain, modern colloquial Spanish use of the term "Moro" is derogatory for Moroccans in particular and North Africans in general. Similarly, in modern, colloquial Portuguese, the term "Mouro" was primarily used as a designation for North Africans and secondarily as a derogatory and ironic term by northern Portuguese to refer to the inhabitants of the southern parts of the country (Lisbon, Alentejo and Algarve). However, this designation has gained more acceptance in the South.

In the Philippines, a former Spanish colony, many residents call the local Muslim population in the Southern islands Moros. They also self-identify that way (see Muslim Filipino). The term was introduced by the Spanish colonizers. Within the context of Portuguese colonization, in Sri Lanka (Portuguese Ceylon), Muslims of Arab origin are called Moors (see Sri Lankan Moors).

Moreno can mean dark-skinned in Spain and Portugal, as well as in Brazil. Also in Spanish, morapio is a humorous name for "wine", especially that which has not been "baptized" or mixed with water, i.e., pure unadulterated wine. Among Spanish speakers, moro ("Moor") came to have a broader meaning, applied to both Moros of Mindanao in the Philippines, and the moriscos of Granada. Moro is refers to all things dark, as in "Moor", moreno, etc. It was used as a nickname; for instance, the Milanese Duke Ludovico Sforza was called Il Moro because of his dark complexion.

In Portugal and Spain, mouro (feminine, moura) may also refer to supernatural beings known as enchanted moura, where "moor" implies 'alien' and 'non-Christian'; These beings were siren-like fairies with golden or reddish hair and a fair face. They were believed to have magical properties. From this root, the name moor is also applied to unbaptized children, meaning not Christian. In Basque, mairu means moor and also refers to a mythical people.

Moors is also a term used to identify Muslims in Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan Moors are 12% of the population. The Moors in Sri Lanka are descendants of Arab traders who settled in Sri Lanka in the mid-6th century. When the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, they labelled the Muslims in the island as Moors as they saw them resembling the Moors in North Africa. The Sri Lankan government to this day identifies the Muslims in Sri Lanka as "Ceylon Moors"

The Goan Muslims - a minority community who follow Islam in the western Indian coastal state of Goa are commonly referred as Moir (Template:Lang-knn) by Goan Catholics and Hindus.. Moir is derived from the Portuguese word mouro (Moors).

Moors of Iberia

Further information: Umayyad conquest of Hispania and Al-Andalus

In 711 CE, the now Islamic Moors came from the North African country Morocco and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to get into the Iberian Peninsula and in a series of raids conquered Visigothic Christian Hispania. Their general, Tariq ibn-Ziyad, brought most of Iberia under Islamic rule in an eight-year campaign. They moved northeast across the Pyrenees Mountains, but were defeated by the Frank Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732.

The Moorish state fell into civil conflict in the 750s. The Moors ruled in North Africa and in most of the Iberian peninsula for several decades. They were resisted in areas in the northwest (such as Asturias, where they were defeated at the battle of Covadonga) and the largely Basque regions in the Pyrenees. Though the number of Moor colonists was small, many native Iberian inhabitants converted to Islam. According to Ronald Segal, by 1000, some 5 million of Iberia's 7 million inhabitants, most of them descended from indigenous Iberian converts, were Muslim. There were also West Africans from Mali and Niger who had been absorbed into the Almoravid dynasty, which was a Berber dynasty and a part of the Iberian Peninsula during Al-Andalus.

In a process of decline, the Al Andalus had broken up into a number of Islamic-ruled fiefdoms, or taifas, which were partly consolidated under the Caliphate of Córdoba.

The Asturias, a small northwestern Christian Iberian kingdom, initiated the Reconquista (the "reconquest") soon after the Islamic conquest in the 8th century. Christian states based in the north and west slowly extended their power over the rest of Iberia. Navarre, Galicia, León, Portugal, Aragón, Marca Hispanica, and Castile began a process of expansion and internal consolidation during the next several centuries under the flag of Reconquista.

In 1212, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of Alfonso VIII of Castile drove the Muslims from Central Iberia. The Portuguese side of the Reconquista ended in 1249 with the conquest of the Algarve (Arabic الغرب – Al-Gharb) under Afonso III. He was the first Portuguese monarch to claim the title "King of Portugal and the Algarve".

The Moorish Kingdom of Granada continued for three more centuries in southern Iberia. On January 2, 1492, the leader of the last Muslim stronghold in Granada surrendered to armies of a recently united Christian Spain (after the marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the Catholic Monarchs). They forced the remaining Jews to leave Spain, convert to Roman Catholic Christianity or be killed for not doing so. To exert social and religious control, in 1480, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to allow the Inquisition in Spain. Granada's Muslim population rebelled in 1499. The revolt lasted until early 1501, giving the Castilian authorities an excuse to void the terms of the Treaty of Granada (1491). In 1501 Castilian authorities delivered an ultimatum to Granada's Muslims: they could either convert to Christianity or be expelled.

The Inquisition was aimed mostly at Jews and Muslims who had overtly converted to Christianity but were thought to be practicing their faiths secretly. They were respectively called marranos and moriscos. However, in 1567 King Philip II directed Moriscos to give up their Arabic names and traditional dress, and prohibited the use of the Arabic language. In reaction, there was a Morisco uprising in the Alpujarras from 1568 to 1571. In the years from 1609 to 1614, the government expelled Moriscos. The historian Henri Lapeyre estimated that this affected 300,000 out of an estimated total of 8 million inhabitants.

Many Muslims converted to Christianity and remained permanently in Iberia. This is indicated by a "high mean proportion of ancestry from North African (10.6%)" that "attests to a high level of religious conversion (whether voluntary or enforced), driven by historical episodes of social and religious intolerance, that ultimately led to the integration of descendants."

In the meantime, the tide of Islam had rolled not just to Iberia, but also eastward, through India, the Malayan peninsula, and Indonesia up to the Philippines. This was one of the major islands of an archipelago which the Spaniards had reached during their voyages westward from the New World. By 1521, the ships of Magellan and other Spanish explorers had reached that island archipelago, which they named Las Islas Filipinas, after Philip II of Spain. In Mindanao, the Spaniards named the kris-bearing people as Moros or 'Moors'. Today in the Philippines, this ethnic group of people in Mindanao, who are generally Muslims, are called 'Moros'. This identification of Islamic people as Moros persists in the modern Spanish language spoken in Spain, and as Mouros in the modern Portuguese language. See Reconquista, and Maure.

According to historian Richard A. Fletcher, "the number of Arabs who settled in Iberia was very small. 'Moorish' Iberia does at least have the merit of reminding us that the bulk of the invaders and settlers were Moors, i.e., Berbers from Algeria and Morocco."

The initial rule of the Moors in the Iberian peninsula under this Caliphate of Córdoba is regarded as tolerant in its acceptance of Christians, Muslims and Jews living in the same territories. The Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed in 1031 and the Islamic territory in Iberia fell under the rule of the Almohad dynasty in 1153. This second stage inaugurated an era of Moorish rulers guided by a version of Islam that left behind the tolerant practices of the past.

-

Othello, the Moor and Desdemona, his Venetian wife, from William Shakespeare's play Othello

Othello, the Moor and Desdemona, his Venetian wife, from William Shakespeare's play Othello

-

"Batalla del Puig" (c. 1410-1420), depicting a battle from the Reconquista

"Batalla del Puig" (c. 1410-1420), depicting a battle from the Reconquista

-

Tariq ibn-Ziyad was the Moor general who led the conquest of Visigothic Spain in the early 8th century

Tariq ibn-Ziyad was the Moor general who led the conquest of Visigothic Spain in the early 8th century

-

Moors in Spain playing chess, from the Book of Games

Moors in Spain playing chess, from the Book of Games

-

The Moors request permission from James I of Aragon

The Moors request permission from James I of Aragon

-

"Wild Men and Moors" tapestry, c. 1400

"Wild Men and Moors" tapestry, c. 1400

-

Christian and Moor playing lutes, 13th century

Christian and Moor playing lutes, 13th century

-

Riyad the Moor receiving a letter from Shanul in Hadith Bayad wa Riyad

Riyad the Moor receiving a letter from Shanul in Hadith Bayad wa Riyad

-

Muhammad XII of Granada, last Muslim sultan in Spain

Muhammad XII of Granada, last Muslim sultan in Spain

-

Leo Africanus, born in Granada

Leo Africanus, born in Granada

Moors of Sicily

See also: History of Islam in southern Italy, left, and Arab-Norman culture

The first Muslim conquest of Sicily and parts of southern Italy lasted 75 years (827–902). By 827, Sicily was almost entirely in control of the Aghlabids with the exception of some minor strongholds in the rugged interior until 909 when it was then replaced by Shiite Fatimids. Four years later, the Fatimid governor was ousted from Palermo when the island declared its independence under Emir Ahmed ibn-Kohrob.

In 1038, a Byzantine army under George Maniaces crossed the strait of Messina. This included a corps of Normans which saved the situation in the first clash against the Muslims from Messina. After another decisive victory in the summer of 1040, Maniaces halted his march to lay siege to Syracuse. Despite his conquest of the latter, Maniaces was removed from his position, and the subsequent Muslim counter-offensive reconquered all the cities captured by the Byzantines.

The Norman Robert Guiscard, son of Tancred, invaded Sicily in 1060. The island was split between three Arab emirs, and the Christian population in many parts of the island rose up against the ruling Muslims. One year later, Messina fell, and in 1072, Palermo was taken by the Normans. The loss of the cities, each with a splendid harbor, dealt a severe blow to Muslim power on the island. Eventually all of Sicily was taken. In 1091, Noto in the southern tip of Sicily and the island of Malta, the last Arab strongholds, fell to the Christians.

Islamic authors would marvel at the tolerance of the Norman kings of Sicily. Ibn al-Athir wrote: "They were treated kindly, and they were protected, even against the Franks. Because of that, they had great love for king Roger."

Many repressive measures were introduced by Frederick II to please the popes who were intolerant of Islam in the heart of Christendom. This resulted in a rebellion by Sicilian Muslims, which in turn triggered organized resistance and systematic reprisals and marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The Muslim problem characterized Hohenstaufen rule in Sicily under Henry VI and his son Frederick II. The complete eviction of Muslims and the annihilation of Islam in Sicily was completed by the late 1240s when the final deportations to Lucera took place.

Architecture

Main article: Moorish architecture

Moorish architecture is the articulated Islamic architecture of North Africa and parts of Spain and Portugal where the Moors were dominant between 711 and 1492. The best surviving examples are La Mezquita in Córdoba and the Alhambra palace (mainly 1338–1390), and also the Giralda in 1184. Other notable examples include the ruined palace city of Medina Azahara (936–1010), the church (former mosque) San Cristo de la Luz in Toledo, the Aljafería in Saragossa and baths at for example Ronda and Alhama de Granada.

Moors in heraldry

Main article: Maure

Moors—or more frequently their heads, often crowned—appear with some frequency in medieval European heraldry. The term ascribed to them in Anglo-Norman blazon (the language of English heraldry) is maure, though they are also sometimes called moore, blackmoor, blackamoor or negro. Maures appear in European heraldry from at least as early as the 13th century, and some have been attested as early as the 11th century in Italy, where they have persisted in the local heraldry and vexillology well into modern times in Corsica and Sardinia.

Armigers bearing moors or moors' heads may have adopted them for any of several reasons, to include symbolizing military victories in the Crusades, as a pun on the bearer's name in the canting arms of Morese, Negri, Saraceni, etc., or in the case of Frederick II, possibly to demonstrate the reach of his empire. The arms of Pope Benedict XVI feature a moor's head, crowned and collared red, in reference to the arms of Freising, Germany. In the case of Corsica and Sardinia, the blindfolded moors' heads in the four quarters have long been said to represent the four Moorish emirs who were defeated by Peter I of Aragon in the 11th century, the four moors' heads around a cross having been adopted to the arms of Aragon around 1281–1387, and Corsica and Sardinia having come under the dominion of the king of Aragon in 1297. In Corsica, the blindfolds were lifted to the brow in the 18th century as a way of expressing the island's newfound independence

The use of moors (and particularly their heads) as a heraldic symbol has been deprecated in modern North America, where racial stereotypes have been influenced by a history of Trans-Atlantic slave trade and racial segregation, and applicants to the College of Arms of the Society for Creative Anachronism are urged to use them delicately to avoid creating offensive images.

Population

Populations in Carthage circa 200 BC and northern Algeria 1500 BC were diverse. As a group, they plotted closest to the populations of Northern Egypt and intermediate to Northern Europeans and tropical Africans: "the data supported the comments from ancient authors observed by classicists: everything from fair-skinned blonds to peoples who were dark-skinned 'Ethiopian' or part Ethiopian in appearance." Modern evidence shows a similar diversity among present North Africans. Moreover, this diversity of phenotypes and peoples was probably due to in situ differentiation, not foreign influxes. Foreign influxes are thought to have had an impact on population make-up, but did not replace the indigenous Berber population.

Notable Moors

- Tariq ibn Ziyad, Moorish general who defeated the Visigoths and conquered Hispania in 711.

- Abd ar-Rahman I, founder of the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba in 756; along with its succeeding Caliphate of Córdoba, the dynasty ruled Islamic Iberia for three centuries.

- Ibn al-Qūṭiyya, Andalusian historian and grammarian.

- Yahya al-Laithi, Andalusian scholar who introduced the Maliki school of jurisprudence in Al-Andalus.

- Abbas Ibn Firnas, 810–887, Berber inventor and aviator who invented an early parachute and made the first attempt at controlled flight with a hang glider.

- Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti, died 1007, Andalusian writer believed to have been the author of the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity and the Picatrix.

- Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis), Andalusian physician and surgeon who established the discipline of surgery as a profession with his Al-Tasrif in 1000.

- Said Al-Andalusi, 1029–1070, Andalusian Qadi, historian, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer.

- Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī (Arzachel), 1029–1087, Andalusian astronomer and engineer who developed the equatorium and universal (latitude-independent) astrolabe and compiled a Zij later used as a basis for the Tables of Toledo.

- Artephius, circa 1126, Andalusian scientist known as the author of numerous works of Alchemical texts, now extant only in Latin.

- Ibn Bajjah (Avempace), died 1138, Andalusian physicist and polymath whose theory of motion, including the concept of a reaction force, influenced the development of classical mechanics.

- Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar), 1091–1161, Andalusian physician and polymath who discovered the existence of parasites and pioneered experimental surgery.

- Muhammad al-Idrisi, circa 1100–1166, Moorish geographer and polymath who drew the Tabula Rogeriana, the most accurate world map in pre-modern times.

- Ibn Tufail, circa 1105–1185, Arabic writer and polymath who wrote Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, the first philosophical novel.

- Averroes (Ibn Rushd), 1126–1198, classical Islamic philosopher and polymath who wrote The Incoherence of the Incoherence and the most extensive Aristotelian commentaries, and established the school of Averroism.

- Ibn al-Baitar, died 1248, Andalusian botanist and pharmacist who compiled the most extensive pharmacopoeia and botanical compilation in pre-modern times.

- Ibn Khaldun, a pioneer of the social sciences and forerunner of sociology, historiography and economics, who wrote the Muqaddimah in 1377.

- Abū al-Hasan ibn Alī al-Qalasādī, 1412–1486, Moorish mathematician who took the first steps toward the introduction of algebraic symbolism.

- Leo Africanus, 1494–1554, Andalusian geographer, author and diplomat, who was captured by Spanish pirates and sold as a slave, but later baptized and freed.

- Estevanico, also referred to as "Stephen the Moor", was an explorer in the service of Spain of what is now the southwest of the United States.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki table code? |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Notes

References

- The Story of the Moors in Spain(Illustrated). Stanley Lane-Poole, Arthur Gilman. Introduction by John G Jackson:"In ancient times, Africans in general were called Ethiopian; in medieval times most Africans were called Moors; in modern times some Africans were called Negroes."

- "Assessment of the status, development and diversification of fisheries-dependent communities: Mazara del Vallo Case study report" (PDF). European Commission. 2010. p. 2. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

In the year 827, Mazara was occupied by the Arabs, who made the city an important commercial harbor. That period was probably the most prosperous in the history of Mazara.

- ^ Menocal, Maria Rosa (2002). "Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain". Little, Brown, & Co. ISBN 0-316-16871-8 page 241

- Pieris, P.E. "Ceylon and the Hollanders 1658-1796". American Ceylon Mission Press, Tellippalai Ceylon 1918

- Ross Brann, "The Moors?", Andalusia, New York University. Quote: "Andalusi Arabic sources, as opposed to later Mudéjar and Morisco sources in Aljamiado and medieval Spanish texts, neither refer to individuals as Moors nor recognize any such group, community or culture."

- Josiah Blackmore (Fall–Winter 2006). "Imaging the Moor in Medieval Portugal". Diacritics. 36 (3/4): 27–43.

Zurara refers to the Sub-Sarahan Africans inhabiting these lands alternately as negros (blacks), guinéus (Guineans), or mouros (Moors).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Menocal, Maria Rosa (2002). "Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain" page 16 http://www.barnesandnoble.com/sample/read/9780316092791

- Richard A Fletcher: Moorish Spain. University of California Press, 2006. page 1. http://books.google.com/books?id=wrMG-LfuU7oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Online Etymology Dictionary.

- in either direction, i.e. the adjective (which appears only late) might be derived from the ethnonym, much like the later Romance terms for "dark-skinned"; etymonline.com: "perhaps a native name, or else cognate with mauros 'black' (but this adjective only appears in late Greek and may as well be from the people's name as the reverse)."

- For an introduction to the culture of the Azawagh Arabs, see: Rebecca Popenoe, Feeding Desire — Fatness, Beauty and Sexuality among a Saharan People. Routledge, London (2003) ISBN 0-415-28096-6

- Simms, Karl (1997). Translating sensitive texts: linguistic aspects. Rodopi. p. 144. ISBN 978-90-420-0260-9.

- Warwick Armstrong, James Anderson (2007). Geopolitics of European Union enlargement: the fortress empire. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-415-33939-1.

- Wessendorf, Susanne (2010). The multiculturalism backlash: European discourses, policies and practices. Taylor & Francis. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-415-55649-1.

- Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou, Ricard Zapata-Barrero (2006). Multiculturalism, Muslims and citizenship: a European approach. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-415-35515-5.

- Bekers, Elisabeth (2009). Transcultural modernities: narrating Africa in Europe. Rodopi. p. 14. ISBN 978-90-420-2538-7.

- Xosé Manuel González Reboredo, Leyendas Gallegas de Tradición Oral (Galician Legends of the Oral Tradition), Galicia: Editorial Galaxia, 2004, p. 18, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010 Template:Es icon

- Rodney Gallop, Portugal: A Book of Folkways, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 1936; reprint CUP Archives, 1961, Googlebooks, accessed 12 Jul 2010.

- Francisco Martins Sarmento, "A Mourama", in Revista de Guimaraes, No. 100, 1990, Centro de Estudos de Património, Universidade do Minho, accessed 12 Jul 2010 Template:Pt icon

- Euskadi.net Template:Es icon

- A. Hussein 'From where did the moors come from?', http://www.lankalibrary.com/cul/muslims/moors.htm

- Richard A Fletcher: Moorish Spain. 1992. page 1. http://books.google.com/books?id=wrMG-LfuU7oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Ivan Van Sertima (1992). The Golden Age of the Moor. Transaction Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4128-1536-9.

- Ronald Segal, Islam's Black Slaves (2003), Atlantic Books, ISBN 1-903809-81-9

- See History of Al-Andalus.

- Adams et al., "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula", Cell, 2008. Quote: "Admixture analysis based on binary and Y-STR haplotypes indicates a high mean proportion of ancestry from North African (10.6%) ranging from zero in Gascony to 21.7% in Northwest Castile."

- Elena Bosch, "The religious conversions of Jews and Muslims have had a profound impact on the population of the Iberian Peninsula", University of , 2008, Quote: "The study shows that religious conversions and the subsequent marriages between people of different lineage had a relevant impact on modern populations both in Spain, especially in the Balearic Islands, and in Portugal."

- Richard Fletcher. Moorish Spain p. 10. University of California Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-520-08496-4

- Granada by Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906 ed.

- Aubé, Pierre (2006). Les empires normands d’Orient. Editions Perrin. p. 168. ISBN 2-262-02297-6.

- Curl p. 502.

- Pevsner, The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture.

- Parker, James. "Man". A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ^ "Africans in medieval & Renaissance art: the Moor's head". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- Mons. Andrea Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo. "Coat of Arms of His Holiness Benedict XVI". The Holy See. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- Sache, Ivan (2009-06-14). "Corsica (France, Traditional province)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- Curry, Ian (2012-03-18). "Blindfolded Moors - The Flags of Corsica and Sardinia". Vaguely Interesting. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- In his July 15, 2005 blog article "Is that a Moor's head?", Mathew N. Schmalz refers to a discussion on the American Heraldry Society's website where at least one participant described the moor's head as a "potentially explosive image".

- "Part IX: Offensive Armory". Rules for Submissions of the College of Arms of the Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- G. Mokhtar. General History of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa, p. 427.

- "Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 83:35-48 (1990).

- Furtado, A. D. (1981). Goa, yesterday, to-day, tomorrow: an approach to various socio-economic and political issues in Goan life & re-interpretation of historical facts. Furtado's Enterprises. pp. 254 pages(page xviii).

Bibliography

- This section's bibliographical information is not fully provided. If you know these sources and can provide full information, you can help Misplaced Pages by completing it.

- Jan R. Carew. Rape of Paradise: Columbus and the birth of racism in America. Brooklyn, NY: A&B Books, c. 1994.

- David Brion Davis, "Slavery: White, Black, Muslim, Christian." New York Review of Books, vol. 48, #11 July 5, 2001. Do not have exact pages.

- Herodotus, The Histories

- Shomark O. Y. Keita, "Genetic Haplotypes in North Africa"

- Shomarka O. Y. Keita, "Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 83:35-48 1990.

- Shomarka O. Y. Keita, "Further studies of crania from ancient northern Africa: an analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs, using multiple discriminant functions." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 87: 345-54, 1992.

- Shomarka O. Y. Keita, "Black Athena: race, Bernal and Snowden." Arethusa 26: 295-314, 1993.

- Bernard Lewis, "The Middle East".

- Bernard Lewis. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. NY: Norton, 1982. Also an article with the same title published in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 20(1/3): 409-16, 1957.

- Bernard Lewis, "Race and Slavery in Islam".

- Stanley Lane-Poole, assisted by E. J. W. Gibb and Arthur Gilman. The Story of Turkey. NY: Putnam, 1888.

- Stanley Lane-Poole. The Story of the Barbary Corsairs. NY: Putnam,1890.

- Stanley Lane-Poole, The History of the Moors in Spain.

- J. A. (Joel Augustus) Rogers. Nature Knows No Color Line: research into the Negro ancestry in the white race. New York: 1952.

- Ronald Segal. Islam's Black Slaves: the other Black diaspora. NY: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001.

- Ivan Van Sertima, ed. The Golden Age of the Moor. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1992. (Journal of African civilizations, vol. 11).

- Frank Snowden. Before Color Prejudice: the ancient view of blacks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1983.

- Frank Snowden. Blacks in antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman experience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1970.

- David M. Goldenberg. The Curse of Ham: race and slavery in early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c2003.

- Lucotte and Mercier, various genetic studies

- Eva Borreguero. "The Moors Are Coming, the Moors Are Coming! Encounters with Muslims in Contemporary Spain." p. 417-32 in Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, 2006, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 417–32.

- "The Moors" by Ross Brann, published on New York University website.

External links

- SIGILLUM SECRETUM (Secret Seal): On the image of the Blackamoor in European Heraldry, a PBS article.

- Encyclopedia - Britannica Online Encyclopedia (2006)

- Moors, Classic Encyclopedia (1911)

- Khalid Amine, Moroccan Shakespeare: From Moors to Moroccans. Paper presented at an International Conference Organized by The Postgraduate School of Critical Theory and Cultural Studies, University of Nottingham, and The British Council, Morocco, 12–14 April 2001.

- Africans in Medieval & Renaissance Art: The Moor's Head, Victoria and Albert Museum (n.d)