| Revision as of 03:08, 30 July 2014 editCherkash (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users30,132 editsm fixed dashes using a script← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:23, 30 July 2014 edit undo89.139.184.192 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 165: | Line 165: | ||

| {{S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Series}} | {{S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Series}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 19:23, 30 July 2014

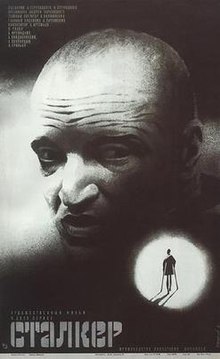

1979 Soviet Union film| Stalker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Written by | Arkadi Strugatsky Boris Strugatsky |

| Produced by | Aleksandra Demidova |

| Starring | Alexander Kaidanovsky Anatoli Solonitsyn Nikolai Grinko |

| Cinematography | Alexander Knyazhinsky |

| Edited by | Lyudmila Feiginova |

| Music by | Eduard Artemyev |

| Production company | Mosfilm |

| Release dates | May 1979 (1979-05) Dom Kino, Moscow |

| Running time | 163 min. |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Budget | 1,000,000 SUR |

Stalker (Russian: Сталкер, IPA: [ˈstɑlkʲɪr]) is a 1979 art film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, with a screenplay written by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, loosely based on their novel Roadside Picnic. It depicts an expedition led by the Stalker to take his two clients to a site known as the Zone, which has the supposed potential to fulfill a person's innermost desires.

The title of the film, which is the same in Russian and English, is derived from the English word to stalk in the long-standing meaning of approaching furtively, much like a hunter. In the film a stalker is a professional guide to the zone, someone who crosses the border into the forbidden zone with a specific goal. The meaning of the word 'stalk' was derived from its use by the Strugatsky brothers for their novel Roadside Picnic (1972), as an allusion to Rudyard Kipling's character Stalky from the "Stalky & Co." stories. Сталки (stálki) was well remembered by the Strugatskys from their childhood, when they read the stories in their Russian translation. In Roadside Picnic, сталкер was a common nickname for men engaged in the illegal trade of prospecting for and smuggling of alien artifacts from the mysterious and dangerous "Zone".

Plot summary

The Stalker (Alexander Kaidanovsky) works as a guide who leads people through "the Zone", an area where the normal laws of physics no longer apply – to encounter "the Room", said to grant the wishes of anyone who steps inside. In his home with his wife and daughter, the Stalker's wife (Alisa Freindlich) begs him not to go into the Zone but he ignores her pleas.

The Stalker meets "the Writer" (Anatoly Solonitsyn) and "the Professor" (Nikolai Grinko), his next clients for a trip into the Zone, in a rundown bar. The three of them evade a military blockade that guards the Zone, attracting gunfire from the guards as they go, and then ride into the heart of the Zone on a railway work car.

The Stalker tells his clients they must do exactly as he says to survive the dangers that lie ahead, which are invisible. The Stalker tests for "traps" by throwing metal nuts tied to strips of cloth ahead of them. The Writer is skeptical that there is any real danger, whilst the Professor generally follows the Stalker's advice.

As they travel the three men discuss their reasons for wanting to visit the Room. The Writer expresses concern that he is losing his inspiration while the Professor's desires are not certain though he reluctantly agrees to countless pleas of the writer that he hopes to win a Nobel prize. The Stalker insists that he has no motive beyond aiding the desperate. At times he refers to a previous Stalker named Porcupine who led his brother to his death in the Zone, visited the Room, gained a lot of money, and then hanged himself. It appears the Room fulfills all of the wishes of the visitor, the problem being that these might not be consciously expressed wishes, but the true unconscious ones. When the Writer later confronts the Stalker about his knowledge of the Zone and the Room he replies that it all comes from Porcupine.

After traveling through subterranean tunnels the three men reach their destination, which lies inside a decayed industrial building. In a small antechamber a phone begins to ring. The Writer answers and speaks into the phone, stating that "this is not the clinic", before hanging up. The surprised Professor decides to use the phone to ring a colleague. In the ensuing conversation he reveals his true intention. He has brought a nuclear weapon with him and intends to destroy the Room for fear it might be used by evil men. The three fight verbally and physically in a larger antechamber just outside their goal. As they recover from their exertions Writer has a timely revelation about the room's true nature. He explains that despite the man's conscious motives, the room fulfilled Porcupine's secret desire for wealth instead of bringing back his brother from death, and that Porcupine's suicide was inspired by the resulting guilt. He further reasons that the Room is useless to the ambitious and is only dangerous to those who seek it. With his earlier fears thus assuaged the Professor gives up on his plan. Instead he disassembles his bomb and scatters its pieces. The men sit before the doorway and never enter. Rain begins to fall into the Room through its ruined ceiling, then gradually fades away.

The Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor are shown to be back in the bar and are met by the Stalker's wife and daughter. A black dog that followed the three men through the Zone is now in the bar with them. When his wife asks where he got it the Stalker declares it became attached to him and he could not leave it behind. As the Stalker departs the bar with his family and dog we see that his daughter, nicknamed "Monkey", is crippled and cannot walk unaided.

Later, when the Stalker's wife tells him she would like to visit the Room, he expresses doubts about the Zone; claiming that he fears her dreams will not be fulfilled. As the Stalker sleeps his wife contemplates their relationship in a monologue delivered directly to the camera. She declares she knew full well life with him would be hard, that he would be unreliable and their children could be deformed, but concludes she is better off with him despite their many griefs. Monkey sits alone in the kitchen. She recites a love poem by Fyodor Tyutchev and lays her head on the table. She then appears to psychokinetically push three drinking glasses across it, one after the other, with the last one – the only one which was empty – falling to the floor. It does not break. A train passes by causing the entire apartment to shake, just as it did in the film's opening scene.

Cast

- Alisa Freindlich as the Stalker's Wife

- Alexander Kaidanovsky as the Stalker

- Anatoli Solonitsyn as the Writer

- Nikolai Grinko as the Professor

Supporting actors:

- Natasha Abramova as Monkey, the Stalker's daughter

- Faime Jurno, Y. Kostin and R. Rendi

Production

Writing

The film is loosely based on the novel Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. After reading the novel, initially Tarkovsky recommended it to his friend, the film director Mikhail Kalatozov, thinking that he might be interested in adapting it into a film. Kalatozov, however, could not obtain the rights to the film from the Strugatsky brothers and abandoned the project. Tarkovsky then began to be more and more interested in adapting the novel. He hoped that it would allow him to make a film that conforms to the classical Aristotelian unity, that is the unity of action, the unity of location and the unity of time.

The plot and flow of the film departs considerably from the novel. According to Tarkovsky the film has nothing in common with the novel except for the two words Stalker and Zone.

However, watching the film and reading the novel demonstrates that there are, in fact, several similarities between the novel and the film. In both works, the Zone is guarded by a police or military guard, apparently authorized with deadly force. The Stalker in both works tests the safety of his path by tossing nuts and bolts (tied with scraps of cloth), ensuring that gravity is normal (i.e., the object flies in an expected path.) Also, a character named Hedgehog is a mentor Stalker to the protagonist. In the novel, frequent visitations to the zone increase the likelihood of abnormalities in the visitor's offspring. In the book, the Stalker has a daughter with light hair all over her body, nicknamed "Monkey"—the same nickname used for the Stalker's daughter in the film, though in the film she is crippled. Neither in the novel nor in the film women enter the Zone. Finally, the target of the expedition (the final expedition in the case of the novel) in both works is a wish-granting device.

In Roadside Picnic the site was specifically described as the site of alien visitation; the name of the novel derives from a metaphor proposed by a character who compares the visit to a roadside picnic.

In a sharp departure from the book, the penultimate scene of the movie is a first person monologue by the Stalker's wife, where she looks directly into the camera and explains, with increasing authority, how she met the Stalker and decided to stick with him. It is the only such scene in the entire 160 minutes of the film; the content though is a kind of answer to what the same woman had said in the opening scene, when she blamed her husband for their miseries. It carries clear allusions to Christ (who also called strangers to "follow me") and as some reviewers pointed out, echoes the style of 19th-century Russian novels with their bold and passionate heroines.

An early draft of the screenplay was published as a novel Stalker that differs much from the finished film.

In an interview on the MK2 DVD, production designer Rashit Safiullin describes the Zone as a space in which humans can live without the trappings of society and can speak about the most important things freely.

Production

In an interview on the MK2 DVD, the production designer, Rashit Safiullin, recalls that Tarkovsky spent a year shooting a version of the outdoor scenes of Stalker. However, when the crew got back to Moscow, they found that all of the film had been improperly developed and their footage was unusable. The film had been shot on new Kodak 5247 stock with which Soviet laboratories were not quite familiar.

Even before the film stock problem was discovered, relations between Tarkovsky and Stalker's first cinematographer, Georgy Rerberg, had deteriorated. After seeing the poorly developed material, Rerberg was fired from the production by Tarkovsky. By the time the film stock defect was discovered, Tarkovsky had shot all the outdoor scenes and had to abandon them. Safiullin contends that Tarkovsky was so despondent that he wanted to abandon further production of the film.

After the loss of the film stock, the Soviet film boards wanted to shut the film down, officially writing it off. But Tarkovsky came up with a solution: he asked to make a two-part film, which meant additional deadlines and more funds. Tarkovsky ended up reshooting almost all of the film with a new cinematographer, Aleksandr Knyazhinsky. According to Safiullin, the finished version of Stalker is completely different from the one Tarkovsky originally shot.

The film mixes sepia and color footage; within the Zone, in the countryside, all is colorful, while the outside, urban world is tinted sepia.

The central part of the film, in which the characters move around the Zone, was shot in a few days at two deserted hydro power plants on the Jägala river near Tallinn, Estonia. The shot before they enter the Zone is an old Flora chemical factory in the center of Tallinn, next to the old Rotermann salt storage and the electric plant — now a culture factory where a memorial plate of the film was set up in 2008. Some shots from the Zone were filmed in Maardu, next to the Iru powerplant, while the shot with the gates to the Zone was filmed in Lasnamäe, next to Punane Street behind the Idakeskus. Some shots were filmed near the Tallinn-Narva highway bridge on the Pirita River.

The documentary film Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The Reverse Side of "Stalker" by Igor Mayboroda sheds new light on the production of Stalker and the relationship between Rerberg and Tarkovsky. Rerberg felt that Tarkovsky was not ready for this script. He told Tarkovsky to rewrite the script in order to achieve a good result. Tarkovsky ignored him and continued shooting. After several arguments, Tarkovsky sent Rerberg home. Ultimately, Tarkovsky shot Stalker three times, consuming over 5,000 meters of film. People who have seen both the first version shot by Rerberg (as Director of Photography) and the final theatrical release say that they are almost identical. Tarkovsky sent home other crew members in addition to Rerberg and excluded them from the credits as well.

Several people involved in the film production — including Tarkovsky — had met deaths, which some crew members attribute to the film's long, arduous shooting schedule in toxic locations. Sound designer Vladimir Sharun recalls:

We were shooting near Tallinn in the area around the small river Jägala with a half-functioning hydroelectric station. Up the river was a chemical plant and it poured out poisonous liquids downstream. There is even this shot in Stalker: snow falling in the summer and white foam floating down the river. In fact it was some horrible poison. Many women in our crew got allergic reactions on their faces. Tarkovsky died from cancer of the right bronchial tube. And Tolya Solonitsyn too. That it was all connected to the location shooting for Stalker became clear to me when Larisa Tarkovskaya died from the same illness in Paris.

Style

Like Tarkovsky's other films, Stalker relies on long takes with slow, subtle camera movement, rejecting the use of rapid montage. The film contains 142 shots in 163 minutes, with an average shot length of more than one minute and many shots lasting for more than four minutes.

Almost all of the scenes not set in the Zone are in a high-contrast brown monochrome.

Soundtrack

The Stalker film score was composed by Eduard Artemyev, who had also composed the film scores for Tarkovsky's previous films Solaris and The Mirror. For Stalker Artemyev composed and recorded two different versions of the score. The first score was done with an orchestra alone but was rejected by Tarkovsky. The second score that was used in the final film was created on a synthesizer along with traditional instruments that were manipulated using sound effects. In the final film score the boundaries between music and sound were blurred, as natural sounds and music interact to the point were they are indistinguishable. In fact, many of the natural sounds were not production sounds but were created by Artemyev on his synthesizer. For Tarkovsky music was more than just a parallel illustration of the visual image. He believed that music distorts and changes the emotional tone of a visual image while not changing the meaning. He also believed that in a film with complete theoretical consistency music will have no place and that instead music is replaced by sounds. According to Tarkovsky, he aimed at this consistency and moved into this direction in Stalker and Nostalghia.

In addition to the original monophonic soundtrack, the Russian Cinema Council (Ruscico) created an alternative 5.1 surround sound track for the 2001 DVD release. In addition to remixing the mono soundtrack, music and sound effects were removed and added in several scenes. Music was added to the scene where the three are traveling to the zone on a motorized draisine. In the opening and the final scene Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was removed and in the opening scene in Stalker's house ambient sounds were added, changing the original soundtrack, in which this scene was completely silent except for the sound of a train.

Film score

Initially Tarkovsky had no clear understanding of the musical atmosphere of the final film and only an approximate idea where in the film the music was to be. Even after he had shot all the material he continued his search for the ideal film score, wanting a combination of Oriental and Western music. In a conversation with Artemyev he explained that he needed music that reflects the idea that although the East and the West can coexist, they are not able to understand each other. One of Tarkovsky's ideas was to perform Western music on Oriental instruments, or vice versa, performing Oriental music on European instruments. Artemyev proposed to try this idea with the motet Pulcherrima Rosa by an anonymous 14th century Italian composer dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In its original form Tarkovsky did not perceive the motet as suitable for the film and asked Artemyev to give it an Oriental sound. Later, Tarkovsky proposed to invite musicians from Armenia and Azerbaijan and to let them improvise on the melody of the motet. A musician was invited from Armenia who played the main melody on a tar, accompanied by orchestral background music written by Artemyev. Tarkovsky, who, unusually for him, attended the full recording session, rejected the final result as not what he was looking for.

Rethinking their approach they finally found the solution in a theme that would create a state of inner calmness and inner satisfaction, or as Tarkovsky said "space frozen in a dynamic equilibrium." Artemyev knew about a musical piece from Indian classical music where a prolonged and unchanged background tone is performed on a tambura. As this gave Artemyev the impression of frozen space, he used this inspiration and created a background tone on his synthesizer similar to the background tone performed on the tambura. The tar then improvised on the background sound, together with a flute as a European, Western instrument. To mask the obvious combination of European and Oriental instruments he passed the foreground music through the effect channels of his SYNTHI 100 synthesizer. These effects included modulating the sound of the flute and lowering the speed of the tar, so that what Artemyev called "the life of one string" could be heard. Tarkovsky was amazed by the result, especially liking the sound of the tar, and used the theme without any alterations in the film.

Sound design

The title sequence is accompanied by Artemyev's main theme. The opening sequence of the film showing Stalker's room is mostly silent. Periodically one hears what could be a train. The sound becomes louder and clearer over time until the sound and the vibrations of objects in the room give a sense of a train's passing by without the train's being visible. This aural impression is quickly subverted by the muffled sound of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. The source of this music is unclear, thus setting the tone for the blurring of reality in the film. For this part of the film Tarkovsky was also considering music by Richard Wagner or the Marseillaise. In an interview with Tonino Guerra Tarkovsky said that he wanted "music that is more or less popular, that expresses the movement of the masses, the theme of humanity's social destiny. But this music must be barely heard beneath the noise, in a way that the spectator is not aware of it.". As the sound of the train becomes more and more distant, the sounds of the house, such as the creaking floor, water running through pipes, and the humming of a heater become more prominent. While the Stalker leaves his house and wanders around an industrial landscape, the audience hears industrial sounds such as train whistles, ship foghorns, and train wheels. When the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor set off from the bar in an off-road vehicle, the engine noise merges into an electronic tone. The natural sound of the engine falls off as the vehicle reaches the horizon. Initially almost inaudible, the electronic tone emerges and replaces the engine sound as if time has frozen.

Andrei Tarkovsky in an interview with Tonino Guerra in 1979."I would like most of the noise and sound to be composed by a composer. In the film, for example, the three people undertake a long journey in a railway car. I'd like that the noise of the wheels on the rails not be the natural sound but elaborated upon by the composer with electronic music. At the same time, one mustn't be aware of music, nor natural sounds."

The journey to the Zone on a motorized draisine features a disconnection between the visual image and the sound. The presence of the draisine is registered only through the clanking sound of the wheels on the tracks. Neither the draisine nor the scenery passing by is shown, since the camera is focused on the faces of the characters. This disconnection draws the audience into the inner world of the characters and transforms the physical journey into an inner journey. This effect on the audience is reinforced by Artemyev's synthesizer effects, which make the clanking wheels sound less and less natural as the journey progresses. When the three arrive in the Zone initially, it appears to be silent. Only after some time, and only slightly audibly can one hear the sound of a distant river, the sound of the blowing wind, or the occasional cry of an animal. These sounds grow richer and more audible while the Stalker makes his first venture into the Zone, initially leaving the professor and the writer behind, and as if the sound draws him towards the zone. The sparseness of sounds in the zone draws attention to specific sounds, which, as in other scenes, are largely disconnected from the visual image. Animals can be heard in the distance but are never shown. A breeze can be heard, but no visual reference is shown. This effect is reinforced by occasional synthesizer effects which meld with the natural sounds and blur the boundaries between artificial and alien sounds and the sounds of nature.

After the three travelers appear from the tunnel, the sound of dripping water can be heard. While the camera slowly pans to the right, a waterfall appears. While the visual transition of the panning shot is slow, the aural transition is sudden. As soon as the waterfall appears, the sound of the dripping water falls off while the thundering sound of the waterfall emerges, almost as if time has jumped. In the next scene Tarkovsky again uses the technique of disconnecting sound and visual image. While the camera pans over the burning ashes of a fire and over some water, the audience hears the conversation of the Stalker and the Writer who are back in the tunnel looking for the professor. Finding the Professor outside, the three are surprised to realize that they have ended up at an earlier point in time. This and the previous disconnection of sound and the visual image illustrate the Zone’s power to alter time and space. This technique is even more evident in the next scene where the three travelers are resting. The sounds of a river, the wind, dripping water, and fire can be heard in a discontinuous way that is now partially disconnected from the visual image. When the Professor, for example, extinguishes the fire by throwing his coffee on it, all sounds but that of the dripping water fall off. Similarly, we can hear and see the Stalker and the river. Then the camera cuts back to the Professor while the audience can still hear the river for a few more seconds. This impressionist use of sound prepares the audience for the dream sequences accompanied by a variation of the Stalker theme that has been already heard during the title sequence.

During the journey in the Zone, the sound of water becomes more and more prominent, which, combined with the visual image, presents the zone as a drenched world. In an interview Tarkovsky dismissed the idea that water has a symbolic meaning in his films, saying that there was so much rain in his films because it is always raining in Russia. In another interview, on the film Nostalghia, however, he said "Water is a mysterious element, a single molecule of which is very photogenic. It can convey movement and a sense of change and flux." Emerging from the tunnel called the meat grinder by the Stalker they arrive at the entrance of their destination, the room. Here, as in the rest of the film, sound is constantly changing and not necessarily connected to the visual image. The journey in the Zone ends with the three sitting in the room, silent, with no audible sound. When the sound resumes, it is again the sound of water but with a different timbre, softer and gentler, as if to give a sense of catharsis and hope. The transition back to the world outside the zone is supported by sound. While the camera still shows a pool of water inside the Zone, the audience begins to hear the sound of a train and Ravel's Boléro, reminiscent of the opening scene. The soundscape of the world outside the zone is the same as before, characterized by train wheels, foghorns of a ship and train whistles. The film ends as it began, with the sound of a train passing by, accompanied by the muffled sound of Beethoven's Ninth symphony, this time the Ode to Joy from the final moments of the symphony. As in the rest of the film the disconnect between the visual image and the sound leaves the audience in the unclear whether the sound is real or an illusion.

Distribution

Stalker sold 4.3 million tickets in the Soviet Union.

DVD

- In GDR DEFA did a complete German synchronization of the movie which was shown in cinema 1982. This was used by Icestorm Entertainment on a DVD release, but was heavily criticized for its lack of the original language version, subtitles and had an overall bad image quality.

- RUSCICO produced a version for the international market containing the film on two DVDs with remastered audio and video. It contains the original Russian audio in an enhanced Dolby Digital 5.1 remix as well as the original mono version. The DVD also contains subtitles in 13 languages and interviews with Alexander Knyazhinsky, Rashit Safiullin and Edward Artemiev.

Reception

Officials at Goskino were critical of the film. On being told that it should be faster and more dynamic, Tarkovsky replied:

he film needs to be slower and duller at the start so that the viewers who walked into the wrong theatre have time to leave before the main action starts.

The Goskino representative then explained that he was trying to give the point of view of the audience. Tarkovsky supposedly retorted:

I am only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson and one called Bergman.

Film critic Derek Adams compared Stalker to Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now, also released in 1979, "as a journey to the heart of darkness, is a good deal more persuasive than Coppola's."

Despite the initial mixed reactions, the movie is now hailed as one of the greatest movies ever made. It ranks 29th in the Sight and Sound Greatest Movies list. And it is rated at 100% by Rotten Tomatoes.

Influence

Seven years after the making of the film, the Chernobyl disaster led to the depopulation of a surrounding area (officially called the "Zone of alienation") rather like that in the film. Some of those employed to take care of the abandoned nuclear power plant refer to themselves as "stalkers".

In 2007, Ukrainian developer GSC Game World published S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, an open world first-person shooter video game. The game is loosely based on both the film and the original story, Roadside Picnic, with elements of both works present throughout the game. The plot is markedly different, however, on several key points. The creation of the Zone was due to project worked upon in secret laboratories founded in depopulated areas after explosions at the Chernobyl NPP. The main characters in the game are unrelated to any other characters in either source. The overall storyline of the game is completely new. Moreover, there is far more action and violence than in any previous iteration. This is the point of the game, though, to create an action-packed FPS environment based around the original works. It was met with generally favorable reviews, though bugs in the software may have prevented the piece from attaining more fame. To date, the game has spawned one prequel, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Clear Sky, and one sequel, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Call of Pripyat. In the game, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. stands for "Scavengers, Trespassers, Adventurers, Loners, Killers, Explorers, Robbers".

In 2012 English writer Geoff Dyer published Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room drawing together his personal observations as well as critical insights about the film and the experience of watching it.

Notes

- In the Soviet Union the role of a producer was different from that in Western countries and more similar to the role of a line producer or a unit production manager.

References

- ^ Johnson, Vida T. (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, pp. 139–140, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Johnson, Vida T. (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, pp. 57–58, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gianvito, John (2006), Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, p. 50–54, ISBN 1-57806-220-9

- "сталкер – Wiktionary". En.wiktionary.org. 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- ^ R·U·S·C·I·C·O-DVD of Stalker

- ^ Norton, James, Stalking the Stalker, Nostalghia.com, retrieved September 15, 2010

- Tyrkin, Stas (March 23, 2001), In Stalker Tarkovsky foretold Chernobyl, Nostalghia.com, retrieved May 25, 2009

- Johnson, Vida T. (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, p. 152, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Johnson, Vida T. (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Varaldiev, Anneliese, Russian Composer Edward Artemiev, Electroshock Records, retrieved 2009-06-12

- Tarkovsky, Andrei (1987), Sculpting in Time, translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, University of Texas Press, pp. 158–159, ISBN 0-292-77624-1

- Bielawski, Jan (2001–2002), The RusCiCo Stalker DVD, Nostalghia.com, retrieved 2009-06-14

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Egorova, Tatyana, Edward Artemiev: He has been and will always remain a creator…, Electroshock Records, retrieved 2009-06-07, (originally published in Muzikalnaya zhizn, Vol. 17, 1988)

- Egorova, Tatyana (1997), Soviet Film Music, Routledge, pp. 249–252, ISBN 3-7186-5911-5, retrieved 2009-06-07

- Turovskaya, Maya (1991), 7½, ili filmy Andreya Tarkovskovo (in Russian), Moscow: Iskusstvo, ISBN 5-210-00279-9, retrieved 2009-06-07

- ^ Smith, Stefan (November 2007), "The edge of perception: sound in Tarkovsky's Stalker", The Soundtrack, 1 (1), Intellect Publishing: 41–52, doi:10.1386/st.1.1.41_1

- Mitchell, Tony (Winter 1982–1983), "Tarkovsky in Italy", Sight and Sound, The British Film Institut e: 54–56, retrieved 2009-06-13

- Segida, Miroslava (1996), Domashniaia sinemateka: Otechestvennoe kino 1918–1996 (in Russian), Dubl-D

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tsymbal E., 2008. Tarkovsky , Sculpting the Stalker: Towards a new language of cinema, London, black dog publishing

- Adams, Derek (2006). Stalker, Time Out Film Guide

- Stalker (1979) – Rotten Tomatoes.

- "Johncoulhart.com article". Johncoulthart.com. 2006-12-07. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

External links

- Stalker at IMDb

- Stalker at Rotten Tomatoes

- Template:Allmovie title

- Stalker at Nostalghia.com, a website dedicated to Tarkovsky, featuring interviews with members of the production team

- Template:Et icon Geopeitus.ee – filming locations of Stalker

- Stalker at official Mosfilm site with English subtitles

| Andrei Tarkovsky | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Films |

| ||||||

| Books | |||||||

| Works about | |||||||

| Works by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noon Universe |

| ||||||

| NIICHAVO novels | |||||||

| Other novels | |||||||

| Other adaptations |

| ||||||

| S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series | |

|---|---|

| Games | |

| Related | |