| Revision as of 06:11, 13 October 2014 editKoavf (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,174,994 edits →top← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:28, 13 October 2014 edit undoILIL (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users71,076 edits this album is a specific abstraction; it was scrapped before assembly and as such cannot be referred to as a studio work without inviting many complications; infobox is meant to be a translation of its 1966-1967 recording sessionsNext edit → | ||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| {{Infobox album | {{Infobox album | ||

| | Name = Smile | | Name = Smile | ||

| | Type = |

| Type = Aborted album | ||

| | Artist = ] | | Artist = ] | ||

| | Cover = Beachboys smile cover.jpg | | Cover = Beachboys smile cover.jpg | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| | Recorded = {{Start date|1966|02|17}}–{{Start date|1967|05|18}}, ], ], ], ], and misc. California locales | | Recorded = {{Start date|1966|02|17}}–{{Start date|1967|05|18}}, ], ], ], ], and misc. California locales | ||

| | Genre = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | | Genre = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| | Length = |

| Length = ≤{{Duration|m=40|s=00}} (projected) | ||

| | Label = ]/] (projected) | | Label = ]/] (projected) | ||

| | Producer = ] | | Producer = ] | ||

Revision as of 11:28, 13 October 2014

For the 2011 release of the surviving Smile recordings, see The Smile Sessions.

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

Smile (occasionally typeset with partial capitalization as SMiLE) is a partially recorded album by the Beach Boys originally intended to be the follow-up LP to Pet Sounds. After the Beach Boys' main songwriter Brian Wilson abandoned large portions of music recorded between 1966 and 1967, the group recorded and released the dramatically minimized Smiley Smile album in its place. Several of the tracks eventually found their way onto subsequent Beach Boys albums. As more fans learned of the original Smile, details of its recordings acquired considerable mystique, and it became famous as one of pop music's legendary milestones.

Working with lyricist Van Dyke Parks, Smile was composed as a concept album with a nonlinear narrative, existing today in its unfinished and fragmented state as a series of abstract musical vignettes. Its genesis came during the recording of Pet Sounds, when Wilson began recording a new single: "Good Vibrations". Seventeen sessions took place over four studios at a cost greater than US$50,000 (exceeding US$470,000 today), making it the most expensive single of its time. It was created by an unprecedented recording technique: over 90 hours of tape was recorded, spliced, and reduced into a three-minute pop song. The single quickly became the band's biggest international hit yet. Smile was intended to be produced in a similar fashion: a tone poem Wilson named "a teenage symphony to God," incorporating a diverse range of music styles including psychedelic, doo-wop, barbershop singing, ragtime, yodeling, early American folk, classical music, and avant-garde explorations into noise and musical acoustics.

As a solo artist, Wilson reinterpreted the project for concert performances in 2004, and then followed up with the studio album Brian Wilson Presents Smile. Though it received great critical acclaim, Wilson later admitted that his version differed substantially from how he had originally conceptualized the work during the 1960s. Before his 2004 interpretation, many attempts were made to complete the Beach Boys' Smile without his involvement. It was in the 1980s when bootlegged tracks from Smile began circulating widely among record collectors, inspiring others to assemble their own version using what surviving recordings were available.

On October 31, 2011, The Smile Sessions was released containing an approximation of what the completed album might have sounded like while using Brian Wilson Presents Smile as a template. Along with it came a sequence of newly arranged surviving recordings and many unreleased session highlights and outtakes. It received critical acclaim. In 2012 it was ranked number 381 in Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list. In 2013, it won the Best Historical Album award at the 55th Grammy Awards.

Background

Crucial to the inception and creation of Smile was Wilson's meeting with burgeoning songwriter Van Dyke Parks in February 1966. They had been introduced to each other by mutual friends David Crosby and Terry Melcher, and Parks would often visit Wilson's home while he was working on Pet Sounds. When Wilson realized that Parks had a unique manner of speaking, he asked him if he could write lyrics for "Good Vibrations". Parks declined for the reason that he thought there was nothing he could add to the track. Wilson invited Parks to write lyrics for the new album in the second quarter of 1966 when the project was provisionally called Dumb Angel. This time Parks agreed and the two quickly formed a close and fruitful working relationship.

In preparation for the writing and recording of the album, Wilson purchased about two thousand dollars' worth of marijuana and hashish. In addition, Wilson famously installed a hotboxing tent in his home and relocated a grand piano to a sandbox in his living room. Between April and September 1966, Wilson and Parks spent many "all night sessions" co-writing a number of songs in the sandbox. A coterie eventually formed around Wilson for most of the Smile sessions, which along with Parks included acquaintances Derek Taylor, Paul Williams, Loren Schwartz, Danny Hutton, Jules Siegel, David Anderle, Michael Vosse, and Paul Jay Robbins. Wilson, already an avid reader of literature, continued to indulge himself in works ranging from the I Ching and Subud philosophy, tracts on astrology, detailed charts of the stars and planets, various topics of mysticism, The Little Prince, the novels of Hermann Hesse, works by Kahlil Gibran, Rod McKuen, and Walter Benton's This is My Beloved. In a reported meeting at Wilson's home between him and novelist Thomas Pynchon—a fan of Pet Sounds—the two were so intimidated by each other that "neither of them really said a word all night long."

In October 1966 interviews, Brian Wilson stated that the Beach Boys' next project was to be "a teenage symphony to God," and that, "It will be as much an improvement over Sounds as that was over Summer Days." The project was to have been an album-length suite of songs that were both thematically and musically linked, recorded using the unusual sounds and innovative production techniques that had contributed to the success of "Good Vibrations", and written as an outlet for all of Brian's intellectual occupations at the time. The Smile project held an especially grandiose importance among its participants, as David Anderle recalls, "Smile was going to be a monument. That's the way we talked about it, as a monument."

Recording and production

Further information: Multitrack recording and Wall of SoundWork on what would have been the core album track "Good Vibrations" begun in February 1966 during the Pet Sounds era. Three months later in May, an early tracking of "Heroes and Villains" was attempted. The Smile sessions officially begun on August 3, 1966 with "Wind Chimes", and from then on, Brian Wilson lead a long and complex series of sessions—approximately 50 overall, discounting the 17 sessions needed for "Good Vibrations"—that continued in earnest until April 14, 1967. Sessions occurred mainly at Hollywood recording studios United Western Recorders, Gold Star Studios, Sunset Sound Recorders and CBS Columbia Square. Oftentimes, Chuck Britz and Larry Levine assisted Brian with engineering, who produced every session, while most instrumentation was played by the Wrecking Crew. The vocal sessions for Smile were usually done at CBS Columbia, which had the only 8-track audio recorder available amongst the major recording studios at the time. Although stereo recording was increasingly popular, Wilson always made his final mixes in mono, as did rival producer Phil Spector. Wilson did so for several reasons—he personally felt that mono mixing provided more sonic control over what the listener heard, minimizing the vagaries of speaker placement and sound system quality. It was also motivated by the knowledge that pop radio broadcast in mono, and most domestic and car radios and record players were monophonic. After a final backing track session designated for "Love to Say Dada" on May 18, 1967, Smile was abandoned for good.

Wilson honed his atypical production methods over several years. In the 1960s, it was common for pop music to be recorded in a single take, but the Beach Boys' approach differed. Using multitrack technology, elements such as backing vocals and guitar solos were often recorded independently and would later be combined to the basic track. From 1964 onward Wilson also began to physically cut tape to craft his recordings, allowing hard-to-sing vocal sections to be recorded, cut and attached with sticky tape to the start or endings of songs. By the time of the Summer Days album in 1965, Wilson was becoming more adventurous in his use of tape splicing. With "Good Vibrations", Wilson further expanded his modular approach to recording, experimenting with compiling the finished track by editing together the numerous sections from multiple versions recorded at the lengthy tracking sessions. Instead of taping each backing track as a more-or-less complete performance—as had been the model for previous Beach Boys recordings—he split the arrangement into sections, recording multiple takes of each section and developing and changing the arrangements and the production as the sessions proceeded. He sometimes recorded the same section at several different studios, to exploit the unique sonic characteristics or special effects available in each. Then, he selected the best performances of each section and edited these together to create a composite which combined the best features of production and performance. This meant that each section of the song was presented in its own distinct sonic envelope, rather than the homogeneous production sound of a conventional "one take" studio recording. The cut-up structure and heavily edited production style of Smile was unique for its time in mainstream popular music, and to assemble an entire album from short musical fragments was a bold undertaking. Brian was aware of the techniques of musique concrète and the usage of chance operations in making art. Parks said that the duo was conscious of musique concrete, and that they "were trying to make something of it," naming Brian as a pioneer for its application in popular music. Varispeed was one of many tape effects used during Smile.

—Tom Nolan, Rolling Stone, October 1971wanted to do an album of music built from sound effects...chords spliced together through a whole LP. He had incredible fantasies. He wanted to put everything down on disc, and when he realized he couldn't, he shifted to, "I wanna make films." That was a step easier to capturing more. If you couldn't get a sound from a carrot, you could show a carrot. He would really liked to have made music that was a carrot.

Various surreal comedy skits were recorded during the sessions as part of a "Psycodelic [sic] Sounds" series. An unused skit was also recorded by Brian Wilson with session drummer Hal Blaine to promote a then-proposed "Vega-Tables" single release. Similar experimental recording sessions were devoted to an adventurous sound collage portion of the album. For "The Elements", Wilson instructed others to travel around with a Nagra tape recorder and record the different variations of water sounds that they could find, as Vosse recounts, "I'd come by to see him every day, and he'd listen to my tapes and talk about them. I was just fascinated that he would hear things every once in a while and his ears would prick up and he'd go back and listen again. And I had no idea what he was listening for!" For his use of recorded noise and tape manipulation on Smile, Wilson is considered by American music journalist Paul Williams to be one of the earliest pioneers of sampling. Author Domenic Priore argued that Wilson "manipulated sound effects in a way that would later be extremely successful when Pink Floyd released The Dark Side of the Moon in 1973, the best-selling album of the entire progressive rock period."

Music and lyrics

The Smile recordings are multigenre, and would have incorporated cowboy songs, country, comic songs, doo-wop, barbershop, chanting, noise, cartoons, and field recordings with a unified homage to Americana. According to English musician and ethnomusicologist David Toop, Smile contains traces of Sacred Harp, Shaker hymns, Mele, and Native American singing. He also cited Frank Sinatra, the Lettermen, the Four Freshmen, Martin Denny, Patti Page, Chuck Berry, Spike Jones, Nelson Riddle, Jackie Gleason, Phil Spector, Bob Dylan, the Penguins, and the Mills Brothers as some of the many contradictory templates he's heard "buried within Smile's music legacy," characterized by Wilson's consistent pattern of "cartoon music and Disney influence mutating into avant-garde pop". Professor Kelly Fisher Lowe referred to Smile as an "experimental rock record." Wilson felt that Smile was too advanced for him to consider it pop music, and explained that he admired and was influenced by Johannes Sebastian Bach for his ability to construct a continuum of complex music using simple forms and simple chords.

In 1966 after being asked by a journalist how he would label his new music, Wilson responded, "I'd call it contemporary American music, not rock 'n' roll. Rock 'n' roll is such a worn out phrase. It's just contemporary American." Forty-five years later, Brian questioned a journalist how they would categorize Smile, with their response being "impressionistic psychedelic folk rock," and that while most rock seems to be about adulthood, Smile "expresses what it's like to be a kid in an impressionistic way," and "depicts the psychedelic magic of childhood," to which Wilson replied: "I love that. You coin those just right." Sessions participant Michael Vosse believed that Smile, had it been completed, would have been "basically a Southern California, non-country oriented, gospel album—on a very sophisticated level—because that's what he was doing, his own form of revival music."

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The eclectic selection of instruments in Smile range from classical instrumentation such as harpsichords and clarinet, to African percussion such as conga drums and woodblocks, and occasionally electronic instruments such as Rhodes piano and the Electro-Theremin. The song "Cabinessence" for example features use of fuzz bass, cello, dobro, bouzouki, banjo, upright piano, harmonicas, and accordions. Desiring a delicate approach to sound, Wilson avoided the tradition of using standard rock percussion. In some cases, he opted a keychain to evoke the noise of rhythmic, rattling jewellery ("Surf's Up"), slide whistles as fire sirens ("Fire"), and crunched celery ("Vega-Tables"). Wilson further explored impressionist arranging with voices and other instruments, from using a muted trumpet as a baby's cry ("Look"), to the group roaring farm animal noises ("Barnyard"). Toop likened Smile to Third Stream tone poems "best described in Charles Mingus's term 'jazzical'". Accordingly, there are similar explorations in acoustics evident in the work of composers Charles Ives, Les Baxter, and Richard Maxfield; with Toop considering Smile to be a "descendant" of Arnold Schoenberg, Sun Ra, The Sauter-Finegan Orchestra, Moondog, and Mingus. Parks noted: "The first thing I can remember in the studio was how Brian used tuneful percussion, like a piano or a Chinese gong. Even a triangle has pitch. Brian was very fond of pitched instruments. They reminded me of the orchestrations of the early 20th century done by people like Percy Grainger, the man who wrote 'Country Gardens', [sic] who was infatuated with tuneful percussion. He stood out in my youth as a great composer because of what he did with sound, and Brian was doing that."

Wilson wrote mixed arrangements for exotic percussion, keyboard, woodwind, string, and brass sections, usually altering the conventions in which the instruments are played in an effort to expand their sonic possibilities. Examples of such would be playing an upright bass with a plectrum alongside a tic-tac bass, or muting a piano by taping its strings. In other instances, Wilson experimented with using brass instruments played like a Tibetan horn or an elephant's trumpet. Observable is an exercise featuring toy train whistles, tubas, a duck decoy, and a jug banged on by a mallet with hesitation by one participant, which caused Wilson to stop for a second and remind them: "Remember one thing: There's no rules to this."

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Author Erik Davis wrote of the album's disconnect to contemporary rock music clichés associated with the hippie subculture, noting that "Smile had banjos, not sitars," and "the 'purity' of tone and genetic proximity that smoothed their voices was almost creepy, pseudo-castrato, a 'barbershop' sound that Hendrix, on 'Third Stone From the Sun,' went thumbs down on." Jazz musician and professor Brian Torff noted Smile to contain "choral arranging" and a "rhapsodic Broadway element". Paul Williams agreed that the human voice is palpable on Smile, and suggested that Brian's "fascination with the relationship between music and voice, and a veritable eruption of musical and sonic insights, new language, new combinations" exhibited what he believed to be "a love of the human voice in all its myriad manifestations" ultimately resulting in "a sort of three-ring circus of flashy musical ideas and avant-garde entertainment". In direct contrast to Pet Sounds, Wilson emphasizes vocables over lyrics with an encoded narrative, and in a style not dissimilar to baby talk or Glossolalia. Williams concludes that Smile was to be "perhaps the story of the unnatural love affair between one man's voice and a harpsichord". Online British journal Freaky Trigger put forth: "While the lyrics are usually pretty damned literary, at their most extreme, they’re divorced from any kind of meaning in the straightforward sense." While suggesting that "the line between the sung word and mere sound become criss-crossed and blurred again and again and again ... where the word becomes subservient to sound, which is only six or so steps on the road to sound-for-the-sake-of-sound," and reflecting on the image of "Brian jammin' with Sun Ra and John Cage," the journal concludes that it was a style of music which could be simply classified as doo-wop, a genre that the group had already familiarized themselves in for years. Al Jardine elaborated that there were differences between the vocal arranging on Smile compared to what the group had previously accomplished.

It was just more textural, more complex and it had a lot more vocal movement. "Good Vibrations" is a good example of that. With that song and other songs on Smile, we began to get into more esoteric kind of chord changes, and mood changes and movement. You'll find Smile full of different movements and vignettes. Each movement had its own texture and required its own session. ... "Cabin Essence" was a tough one. Just the alacrity of the parts and the movements. There was wind driven part in the parts around "who ran the iron horse" – a lot of challenging vocal exercises and movements in that one. But we enjoyed those challenges. There was almost like a competition among us between who could do their part better than the other guy – but a healthy one. ... there was one part that I'd forgotten about where we sang this dissonant chord – this strange chord, which sounded like the whistle of a train. It was very clear and it actually sounded like a real train.

Brian Wilson's experiments with psychotropics such as cannabis, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and the amphetamine/barbiturate combination desbutal were influential on the texture and structure of the work, some participants stating lyrical elements stemmed from their use. Writer Bill Tobelman speculated that Smile is filled with coded references to Brian's life and LSD experiences (a presumed Lake Arrowhead, California "trip" being the most important). This is supported by the track "Love to Say Dada", which can be abbreviated as "LSD". He also argues that it was influenced by Wilson's interest in Zen—notably in its use of absurd humor and paradoxical riddles (koans) to liberate awareness from the mind—and that Smile as a whole can be interpreted as an extended Zen koan. Contemporary interviews display Wilson as an avid follower of the rapidly approaching psychedelic scene impending West Coast pop music, and he anticipated that Smile would be the preeminent psychedelic pop art statement. He also believed that psychotropics were closely related to spirituality, citing his own psychedelic experiences which he considered "very religious." In 1966, Wilson prophesied that "psychedelic music will cover the face of the world and color the whole popular music scene. Anybody happening is psychedelic." The Guardian argued that until the negative effects of LSD surfaced in rock music via Skip Spence's Oar (1969) and Syd Barrett's The Madcap Laughs (1970), "artists tactfully ignored the dark side of the psychedelic experience," which could be suggested by Smile in the form of "alternately frantic and grinding mayhem" ("Fire"), "isolated, small-hours creepiness" ("Wind Chimes"), and "weird, dislocated voices" ("Love to Say Dada").

—Michael Vosse, 1969told me that he felt laughter was one of the highest forms of divinity, and that when someone was laughing their connection with the thing that was making them laugh made them more open that they could be at just about any point. Which I agree with. You can find that in all art forms: the minute you have someone laughing you also have them vulnerable, which means either you can shock them, make them laugh more—or at that moment you can be very honest with them. And Brian felt that it was time to do a humor album.

Arthur Koestler's book, The Act of Creation, had a profound effect on Wilson that carried deeply into the Smile project, specifically the human logistics of laughter. Wilson pointed to the book's three-category division of the human mind: Humor, Discovery, and Art; he has admitted that he was most influenced by Koestler's first rule of ego, Humor, as he explained in 2005: "The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler turned me on to some very special things…it explains that people attach their egos to their sense of humor before anything else. After I read it, I saw that trait in many people…a sense of humor is important to understanding what kind of person someone is. Studying metaphysics was also crucial, but Koestler's book really was the big one for me." As a consequence, the Smile songs are replete with word play, puns, colloquialisms, vernacular, double entendres, slang, and miscellaneous dialect. One example is "Vega-Tables", which includes the lines "I'm gonna do well, my vegetables, cart off and sell my vegetables"; the phrase "cart off and" is a bilingual pun on the word kartoffeln, which is German for potatoes. At one stage, Wilson apparently toyed with the idea of devoting Smile as a comedy album and a number of scrapped recordings were made in this vein. David Anderle remembered: "Brian was consumed with humor at the time and the importance of humor. He was fascinated with the idea of getting humor onto a disc and hot to get that disc out to the people."

Concept

—Paul Williams, from Back to the Miracle Factory, c.1993compresses half a dozen different songs into one ("Cabinessence") and at the same time it repeats a single melodic and rhythmic theme (the "Heroes and Villains" chorus) in otherwise separate songs, breaking down the walls that give songs identities without ever offering conceptual ("rock opera") explanation or resolution.

Several key subjects of the album are generally acknowledged both musically and lyrically: Wilson and Parks intended Smile to be explicitly American in style and subject, a conscious reaction to the overwhelming British dominance of popular music at the time. It was conceived as a musical journey across America from east to west, beginning at Plymouth Rock and ending in Hawaii, traversing some of the great themes of modern American history and culture including the impact of white settlement on native Americans, the influence of the Spanish, the Wild West and the opening up of the country by railroad and highway. Specific historical events touched upon range from Manifest destiny, American imperialism, westward expansion, the Great Chicago Fire, and the Industrial Revolution.

In reference to how George Gershwin "Americanized" jazz and classical music, Wilson in his own words intended to "'Americanize' early America and mid-America." Most of the album's thematic direction was given to Parks with hardly any instruction from Wilson. Together, the two desired a back-to-basics approach to songwriting, as Wilson summarized, "We wanted to capture something as basic as the mood of water and fire." Parks said that the duo "kind of wanted to investigate … American images. … Everyone was hung up and obsessed with everything totally British. So we decided to take a gauche route that we took, which was to explore American slang, and that's what we got." He clarified this notion further by saying, "So this is what this stuff was: American music. We would use the thematic America. We would be the Americans. Why do that? Everybody else was getting their snout in the British trough. Everybody wanted to sing 'bettah'', affecting these transatlantic accents and trying to sound like the Beatles. I was with a man who couldn't do that. He just didn't have that option. He was the last man standing. And the only way we were going to get through that crisis was by embracing what they call 'grow where you're planted'."

Aside from focusing on American cultural heritage, Smile's themes include scattered references to parenthood and childhood, physical fitness, world history, poetry, and Wilson's own life experiences. Many traits in Smile lyrics are reminiscent of patrician period imagery and the Romantic poetry movement that began in the mid-to-late 18th century, with the biggest focus being on the Songs of Innocence and of Experience collection of poems written by English poet William Blake. Thematic links to Songs of Innocence and of Experience by concept of childhood and spirituality carry throughout other songs and tracks. However, the piece "My Heart Leaps Up" by William Wordsworth originated the idiom "Child Is Father of the Man" later recycled by Wilson and Parks. Other general Smile themes have been recited by Smile visual artist Frank Holmes to have included "travel, nature, history, communications, love stories, virtue, betrayal, bucolic splendor, astrology, mystery."

Smile drew heavily on American popular music of the past; Wilson's original compositions were interwoven with snippets of significant songs of yesteryear including "The Old Master Painter", the perennial "You Are My Sunshine" (state song of Louisiana), Johnny Mercer's jazz standard "I Wanna Be Around" (recorded by Tony Bennett), "Gee" by the 1950s doo-wop group the Crows and quotations from other 20th century pop culture reference points such as the Woody Woodpecker theme and "Twelfth Street Rag". These references tended to thematically blur with the other Smile elements, and there was no definite line drawn between the established Americana and spirituality themes. Perhaps the least obvious example of this blur would be "The Old Master Painter"—the "master painter" described in the song's lyrics refers to God. This is continued in the lyrics to the Wilson/Parks original "Surf's Up", which imagines religious experience, "canvassing the town", and "brushing the backdrop". Various 18th–20th century works such as "The Pit and the Pendulum", "This Land Is Your Land", "See See Rider", "Frère Jacques", "Auld Lang Syne", "My Prayer", "The Charge of the Light Brigade", and Poor Richard's Almanack are also alluded to in song lyrics or titles.

"The Elements"

"The Elements" was a reputed four-part movement which encompassed the four classical elements: Air, Fire, Earth, and Water. According to Domenic Priore, conversations between him and Van Dyke Parks have told that "The Elements" were meant to invoke the increasing attention to health, fitness, and environmentalism by anti-war peace movements. Alternatively, Darian Sahanaja—a close associate of Wilson and Parks—has said: "Brian never ever referred to any of the pieces as being part of some Elemental concept, and whenever I did bring up the concept he didn’t seem to react to it with any enthusiasm. I brought it up again while Van Dyke was around and didn’t get a clear reaction from him either. My gut feeling is that it was one of many subplots and underlying themes being tossed around back in the day. It does however tie in nicely with the concepts of western expansion, manifest destiny, birth and rebirth, and so I’m sure they would respect a listener’s interpretation." Contemporary statements made by those involved with the original album sessions offer somewhat deeper insight into Smile's elemental suite. As described by David Anderle in an issue of Crawdaddy!:

e was really into the elements. He ran up to Big Sur for a week, just 'cause he wanted to get into that, up to the mountains, into the snow, down to the beach, out to the pool, out at night, running around, to water fountains, to a lot of water, the sky, the whole thing was this fantastic amount of awareness of his surroundings. So the obvious thing was to do something that would cover the physical surroundings. … We were aware, he made us aware, of what fire was going to be, and what water was going to be; we had some idea of air. That was where it stopped. None of us had any ideas as to how it was going to tie together, except that it appeared to us to be an opera. And the story of the fire part I guess is pretty well known by now.

During the latter half of the 1960s, Wilson began an obsession with fitness that led him to move the furniture out of his living room in order to make room for tumbling mats and exercise bars; later briefly serving as the co-owner of his own health food store. Wilson reported in 1967, "I want to turn people on to vegetables, good natural food, organic food. Health is an important element in spiritual enlightenment. But I do not want to be pompous about it, so we will engage in a satirical approach." Derek Taylor remembers: "He'd be sitting with me in this restaurant going on and on about this supposedly strict vegetarian diet of his, preaching vegetarianism at me while at the very same moment he'd be whacking down some massive hamburger."

Track listing

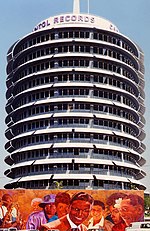

See also: The Smile Sessions § Track listingThe most ambiguous and least realized parts of the 1966 Smile concept was its ambitious narrative, length, track listing, and track order. The material recorded was set to be divided into a then-undecided number of musical suites or movements. No official sequencing was decided in 1967, and although numerous track listing and running orders were eventually established decades later, Brian Wilson has stated that the original Smile would have been "less uplifting" than his finished 2004 version. He also claimed that he and Van Dyke Parks had originally thought of the album as a two-movement rock opera or cantata. Given the technical limitations of record production in 1967 and the sheer bulk of material that was being recorded, Wilson recorded far more music than could possibly have fit on one LP, yet the album was only ever envisaged as being a single LP. In November 1966, Wilson reported: "This LP will include 'Good Vibrations' and ‘Heroes And Villains' and ten other tracks lots of humor – some musical and some spoken. It won't be like a comedy LP- there won't be any spoken tracks as such – but someone might say something in between verses." The 2011 release of the The Smile Sessions compilation proved conclusively that virtually all the musical "components" used to create Wilson's 2004 version of Smile are present in one form or another among the original 1967 recordings. The intended track order and arrangement of the various songs, segments, and link pieces of Smile have remained either inconclusive or mostly forgotten among the people involved. However, the following non-ordered tracks were presented on a handwritten note delivered to Capitol Records by Wilson a few weeks prior to Christmas. It was long considered crucial evidence of Wilson's intentions for the piece, but in 2006 it was discovered Brian had never seen it before. A comparison of the handwriting indicates that it may have been written by Carl Wilson, or possibly Brian's sister-in-law, Diane Rovell:

|

Problems playing this file? See media help.

"Heroes and Villains" was the ultimate keystone for the musical structure of the album, and the considerable time and effort that Wilson devoted to it is indicative of its importance, both as a single and as part of the Smile narrative. Like "Good Vibrations", it was edited together from many discrete sections. Additionally, most individual tracks on Smile were composed as potential sections of "Heroes and Villains". Nearly thirty sessions for the various versions of "Heroes and Villains" spanned from May 1966 to July 1967. There are dozens of takes spanning each section of the song, multiple versions of both the variant sections, and many attempts to splice together final mixes. One of the other centerpieces of Smile was to be "Surf's Up", which had been for many years perceived as the intended ending climax of Smile, preceding a section described as a "choral amen sort of thing." "Good Vibrations" was completed by Wilson and released in October 1966 while Smile sessions were underway.

All of the other tracks were either not recorded or only exist in part-completed form, and many Smile-era recordings lack their full vocal arrangements, lyrics and melodies. Many of the shorter tracks, along with many other brief instrumental and vocal pieces, were evidently intended to serve as bridging sections that would have been edited in to provide links between the major songs. Nearly all of the Smile tracks fluxed in state between August 1966 and May 1967, with the only exception being "Our Prayer": a short hymn intended by Wilson to be the opening "spiritual invocation" of the Smile album. A track entitled "Holidays" was recorded as an oblique instrumental in September 1966, and is one of the few pieces from Smile where every section was performed as part of one whole take. "You're Welcome" is a short chant sung by the Beach Boys over a thumpy background track featuring a glockenspiel and a timpani. The other Wilson brothers also experimented with their own compositions in between sessions for the Smile album, but it's doubtful if they were to have been included in the album. A brief medley of the traditional standards "The Old Master Painter" and "You Are My Sunshine" was also recorded, along with a short instrumental cover version of "I Wanna Be Around".

Artwork and promotion

Capitol began production on a lavish gatefold cover with a twelve-page booklet in December. Considered by some to be one of the one of the most legendary album covers in rock, its artwork was commissioned from Frank Holmes, a friend of Van Dyke Parks he had met at a coffeehouse three years earlier. Holmes based the cover art from an abandoned jewelry store he'd seen near his home in Pasadena, added onto several visual interpretations of the album's lyrics that were illustrated by Holmes for the bonus Smile booklet scheduled for its packaging. According to Michael Vosse, the "Smile shop" portrayed on the cover came from Brian's desire for a humor album, "and everybody who knew anything about graphics, and about art, thought that the cover was not terribly well done... but Brian knew better; he was right. It was exactly what he wanted, precisely what he wanted." The cover image would have been one of the earliest instances of a popular music group featuring original commissioned artwork rather than a photograph of the performers. Parks considered work by Holmes to be the "third equation" of Smile, and that they would have not continued on the project the way they did without thinking of it in cartoon terms, as Parks believes: "To me, it was a musical cartoon, and Frank showed that, without being told anything. There is some reference: Frank was supposed to do something 'light-hearted', but there were no specific instructions and he came up with the perfect video vessel for realizing what we were doing, something I thought was an integral part of the situation. I think that still stands; I think of Smile in visual terms." Capitol later added the repeated written instances of "Good Vibrations" on the album cover, which were not featured on the original design by Holmes. Color photographs of the group were also taken by Guy Webster. 466,000 covers and 419,000 booklets were printed by early January 1967; with the aforementioned track list displayed on the back cover, along with a photographed depiction of the group minus Brian surrounded by astrological symbols. Holmes explains his role in the project:

In around June, I met Brian and Van Dyke, and by October I was done with my work and they were putting things together. It was kind of sporadic: I’d get a little piece of it here and there, and I submitted the cover. Then I had a meeting with Brian and Capitol, and I discussed my idea to put together a booklet of these illustrations to Karl Engemann, I think, and then we went to George Itake, the art director, and explained my concept to him – about the drawing on one side and the photograph on the other. I used to take work over to show Van Dyke what I was working on, from time to time, and one day Brian was there, and Van Dyke introduced me to Brian. "Hey, Brian’s doing this album," he says, "and I’m going to be writing music with him." So I said, "Do you have a cover?" "No." And I said, "Well, let me give you some ideas." So I came up with that store-front idea, and they seemed to like that, and I think Brian took it to Capitol and said they wanted to have this on the cover. ... I thought that was a good image because of the way, any time you go into a store, you’re entering something, and the door opens and you go in, but its designed; it’s like a funnel. So I thought, "Well, this would be a good graphic image on the front cover" – something that would pull you in. I knew that sales were important in selling music. This was something that would be pulling you into the world of Smile – the Smile Shoppe – and it had these little smiles all around. There’s two people in there, too, a husband and wife – a kind of early-Americana, old-style, 19th-century kind of image.

—Derek TaylorI also recall with Brian and Dennis about the Beach Boys never having written surf music or songs about cars; that the Beach Boys had never been involved in any way with the surf and drag fads...they would not concede.

Sometime after Pet Sounds was released, the Beatles' press agent Derek Taylor started working as a publicist for the group, gradually becoming aware of Brian's reputation as a "genius" among musician friends. Taylor was confused, wondering to himself: "'If that's so, why doesn't anyone outside think so?'" In response, Taylor devised a campaign that would reestablish the band's outdated surfing image, and thus promoted Brian as an exceptional "genius" among pop artists, something which Taylor personally believed himself. As a result, the Beach Boys were profiled extensively during the Smile era. Band members Al Jardine, Mike Love, and Bruce Johnston all spoke positively of the album's recording sessions in contemporary music journals, with Dennis Wilson famously confessing to a reporter: "In my opinion it makes Pet Sounds stink—that's how good it is!". The project was chronicled by Jules Siegel in a 1967-published article for Cheetah magazine entitled Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!. In November 1966, Brian Wilson was filmed performing a solo version of "Surf's Up" on grand piano for a CBS News special on popular music: Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution. Although he was filmed in late 1966, the special was not aired until several months later. The month after filming for CBS, the KRLA Beat magazine published a surreal vegetable-themed psychedelic piece written by Wilson. The story described the experiences of "Brian Gemini" as he encountered various characters lurking within the "Vegetable Forest", a few of which were based upon real-life acquaintances Anderle, Vosse, and Hal Blaine.

A short-lived film production company entitled Home Movies was established by the group. It was supposed to have created live action film and television properties which star the group. Only one music video was completed by the company for "Good Vibrations", though various other psychedelic sequences and segments exist.

—Hit Parader, December 1966The Beach Boys' album Smile and single "Heroes And Villains" will make them the greatest group in the world. We predict they'll take over where The Beatles left off.

Some time in December, Brian informed Capitol that Smile would not be ready by January 1, 1967, but he advised that he would deliver it prior to January 15. Capitol continued sending promotional materials to record distributors and dealers, and ads were placed in Billboard and teenage magazines including Teen Set. Within these ads, the album had been compared as an artistic achievement to the films Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, both directed by film auteur Orson Welles. Capitol also circulated a promotional ad for employees at its label, using "Good Vibrations" as the backdrop against a voice-over reciting the album's promotional tagline: "With a happy album cover, the really happy sounds inside, and a happy in-store display piece, you can't miss! We're sure to sell a million units... in January!" Wilson's conception of the work evidently changed around this time.

Project collapse

Once Wilson missed the January deadline, he rigorously continued work mostly on "Heroes and Villains" and "Vega-Tables" as potential singles. Throughout the first half of 1967, the album's release date was repeatedly postponed as Wilson tinkered with the recordings, experimenting with different takes and mixes, unable or unwilling to supply a completed version of the album. Desperate for a new product from the group, EMI released "Then I Kissed Her" as a single without the band's approval. The success of the relatively remedial single—which would ultimately best the chart placement of "Heroes and Villains"—was another potential cause for Wilson abandoning the initially more adventurous sound collage of "Heroes and Villains" and settling for a more traditional song-structure.

—Van Dyke Parks, 1984I walked away from the situation as soon as I realized that I was causing friction between him and his other group members, and I didn't want to be the person to do that. I thought that was Brian's responsibility to bring definition to his own life. I stepped in, perhaps, I took a leap before I looked. I don't know, but that's the way I feel about it.

On April 14, 1967, after gradually distancing himself from Wilson and the group, Van Dyke Parks left the project in the wake of signing a record deal with Warner Bros. Records so he could work on his debut album Song Cycle. As a result of Parks having quit, Brian Wilson lost sight of the album's direction. He went back and forth considering many different ways to execute Smile, fluctuating between ideas such as a sound effects collage, a comedy album, and a "health food" album. Eventually, the number of possible variations for song edits became too overwhelming for him. Audio engineer Mark Linett speculated that Wilson could not have finished the album simply because his ambitions were impossible to fulfill with pre-digital technology, accordingly: "In 1966, meant physically cutting pieces of tape and sticking them back together—which is how all editing was done in those days—but it was a very time-consuming and labor-intensive process, and most importantly made it very hard to experiment with the infinite number of possible ways you could assemble this puzzle."

After undergoing several months of internal conflict, Derek Taylor announced to the British press on May 6, 1967 that the Smile tapes had been destroyed and would not see release. Later that month, Taylor terminated his employment with the group in order to focus his attention on organizing the Monterey Pop Festival, an event the Beach Boys declined to headline at the last minute. This cancellation came to be seen as an admission of the band's failure to integrate with the burgeoning 1960s counterculture, resulting in a cataclysmic blow to their reputation.

A few weeks later, Wilson finalized "Heroes and Villains" as the Beach Boys' next single. In the months leading up to its release, it had garnered a considerable amount of hype, with many publications referring to it as another recording milestone on par with the innovations present in "Good Vibrations". Reflective of the Beach Boys popular status up until May 1967, they had been voted as the world's number one vocal group within readers polls conducted by UK magazine NME; ahead of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. In June 1967, Wilson personally delivered an exclusive acetate of "Heroes and Villains" to radio station KHJ by limousine. As Wilson excitedly offered the vinyl record for radio play, the DJ refused, citing program directing protocols, which Terry Melcher recalls "just about killed ". Upon its release in July, "Heroes and Villains" disappointingly peaked at only number 12 on the Billboard pop charts, and was met with general confusion amongst underwhelming reviews. This included the seminal rock figure Jimi Hendrix negatively describing the single as a "psychedelic barbershop quartet" to NME Wounded by the relative indifference to "Heroes and Villains," Wilson's emotional state began to plummet further, as the band's future manager Jack Rieley wrote for an online Q&A on October 18, 1996:

Brian blirted [sic] it out one evening at , and later spoke about it several times in agonizing detail. He had expected that would be greeted by Capitol as the work which put the Beach Boys on a creative par with the Beatles. All the adoration and promotional backup Capitol was giving the Beatles would also flow to his music because of , he thought. And the public? It would greet with the same level of overwhelming enthusiasm that the Beatles got with record after record. As it was, Capitol execs were divided about . Some loved it but others castigated the track, longing instead for still more surfing/cars songs. The public bought the record in respectable but surely not wowy zowy numbers. For Brian, this was the ultimate failure. His surfing/car songs were the ones they loved the most. His musical growth, unlike that of Messrs. Lennon and McCartney, did not translate into commercial ascendancy or public glory.

Despite Smile's official cancellation in May, Wilson continued working and revising the year's worth of material he had amassed for as long as he could bear its repetitiveness. He then became desensitized to the material, feeling it was increasingly necessary to start all over from scratch. In 1985, Wilson expressed: "Time can be spent in the studio to the point where you get so next to it, you don’t know where you are with it, you decide to just chuck it for a while." Brian gradually retreated from the public eye and over the ensuing years became disabled by his mental health problems to fluctuating degrees. The Smile period is often reported as the pivotal episode in his decline, causing him to become tagged as one of the most notorious celebrity drug casualties of the rock era.

Substance abuse and paranoia

Brian Wilson began to encounter serious problems with Smile around late November 1966. Around this period, Brian was exhibiting consistent signs of depression and paranoia. By the beginning of 1967, Brian's behavior became increasingly erratic, and his use of drugs escalated. Taking advice from his astrologer who told him to beware of "hostile vibrations", Wilson holed up in his bed for days smoking cannabis and eating candy bars. Jules Siegel was exiled from Wilson's social circle on the grounds that his girlfriend had been disrupting Wilson's work through ESP. While such actions were a concern for some of his friends and many similar stories of his sometimes bizarre off-duty behavior became the stuff of legend, those who worked for him during this period have stated that he was totally professional in the studio. Although Wilson's paranoia was consuming him, it was not completely unfounded. Other people have said that he had good reason to be wary of his surroundings, pointing to his high position in the music industry and an instance where the master tapes for "Good Vibrations" had been stolen by an unknown party for three days. Rumors were abound that the Smile tapes were being leaked from their Los Angeles studios, and that Wilson believed – as a result – the 1967 Sagittarius single "My World Fell Down" was a deliberate Smile pastiche. Wilson's ill-perceived security of these studios are said to have contributed to his decision to construct his own personal recording studio.

Reportedly, Brian's first exposure to the Beatles' February 1967 single "Strawberry Fields Forever" affected him. He heard the song while driving his car and pulled over to listen, commenting to his passenger Michael Vosse that the Beatles had "got there first," although he denied the story's accuracy in later years, affirming that the song had not discouraged him. At the time, Brian was reportedly having doubts on whether Smile would still be received as a culturally relevant work among record-buyers and the contemporary rock audience. Parks believes that Derek Taylor facilitated the Beatles with Smile acetates while they were in progress with their 1967 LP Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, explaining: "They heard Smile in part—the first eight-track—up at Armen Steiner's studio at Yucca and Argyle. It was after Brian found out that they had been in the studio, we heard. We walked into the place and heard that the Beatles had been there. We knew that the nest had been found, and Brian was very sad. He felt violated, raped. So we didn't go back there; we took the tapes and Brian got an eight-track machine. It was easier than losing the security he wanted, but the damage had been done." He asserts that Brian's attitude changed completely after the episode, making him "question the loyalties of the people who were working for him," and that to be "invited to a session was a big deal in those days, and certainly to know what Brian’s process was would be something that everybody desired at that time, because he was such an opinion-maker and he was inventing new formats, new ways of working."

—Al Jardine, 1998We started to get indications that Brian was taking some hallucinogens, like LSD and stuff like that—a lot of the writers were doing that at the time—but it took a tremendous toll from him. He drove me around the parking lot of William Morris about twenty times, explaining to me about this great trip he had just taken, and I just wanted to be as far away from that as possible! Because I didn't want to know about it—I wanted the innocence!

Following the recording session for the "Fire" section of "The Elements" at Gold Star Studios on November 28, 1966, Brian became irrationally concerned that the music had been responsible for starting several fires in the neighborhood of the studio. Wilson falsely claimed for many years that he had burned these session tapes, but that was not the case, although he did abandon the "Fire" piece for good. Parks deliberately stayed away from the session—during which Wilson encouraged the musicians to wear toy firemen hats—and that he later described Brian's behavior as "regressive," something which band mates also observed during and after this session. Besides the "Fire" session, Parks was uncomfortable being placed in the middle of the overwhelmingly drugged atmosphere that typical Smile sessions beheld, which he has said to have indulged in only at Wilson's insistence.

David Anderle was head of the Beach Boys' label Brother Records during the period when Brian Wilson was working on the Smile album. Anderle painted a portrait of Wilson, which reportedly frightened him when he saw it, convinced that Anderle had somehow captured his soul on canvas. Anderle would go on to tell Rolling Stone years later that things had not been the same between him and Wilson afterward. In subsequent years, participants have acknowledged that the lack of mental health awareness in the 1960s made it difficult for people to comprehend what was happening to Brian or how to best approach the symptoms that were arising at an overwhelming pace.

Wilson went to see the movie Seconds after hearing that Phil Spector was one of the film's investors. It briefly impacted Wilson, who had entered the theater late, and upon arriving heard Rock Hudson's character "Mr. Wilson" greeted on screen, mistaking that the film was talking directly to him. He would expound on the experience saying that it had "completely blown" his mind, and that, "The whole thing was there. I mean my whole life. Birth and death and rebirth. The whole thing. Even the beach was in it, a whole thing about the beach. It was my whole life right there on the screen. … I mean, look at Spector, he could be involved in it, couldn't he? He's going into films. How hard would it be for him to set up something like that?…You can understand how that movie might get someone upset under those circumstances."

Group and label pressure

In a 2011 press statement, Capitol/EMI admitted: "The reason Smile did not see release in 1967 had more to do with back room business … than anything else." Supplementing Brian's mental and substance abuse issues during these sessions were significant personal, business and legal pressures. In October 1966 the band began establishing Brother Records with noted difficulty, on January 3, 1967 Carl Wilson refused to be drafted for military service, leading to indictment and criminal prosecution which he challenged as a conscientious objector and in March 1967, a lawsuit seeking US$255,000 (US$2,330,000 today) was launched against Capitol Records over neglected royalty payments. Within the lawsuit, there was also an attempt to terminate the band's contract with Capitol, a legacy of Murry's management, prior to its November 1969 expiry. The case was settled out of court, with the band receiving their $200,000 in exchange for Brother Records to distribute through Capitol Records, along with a guarantee that the band produce at least one million dollars profit, which has been recalled as a point "when things started getting bad." Paul Williams saw that "Ironically, the independence that forming Brother Records was supposed to bring to Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys was the very thing that knocked Smile–and the Beach Boys–out of the water. David Anderle's initial idea in the formation of Brother Records was sound, but the time it takes to put this type of thing through the courts was not conducive to the production race that was important during this period of radical change in pop."

—Mike Love, 2006cJust because I said I didn't know what meant didn't mean I didn't like them. I have zero against Van Dyke Parks. That's why I said, "What the fuck does that mean?" It's not meant to be an insult. He didn't get insulted. He just said, "I haven't a clue!"…People don't know the way I think. And they don't give a fuck about the way I think, either. … I was just asking: What did it mean?

Infighting within the group was also a potential factor in the demise of Smile. The December 6, 1966 session for "Cabin Essence" was the scene of an argument between Van Dyke Parks and Mike Love where the latter requested that Parks explain the meaning of the lyrics he was to sing. The event was said by Parks to be the prime catalyst for his reduced involvement in Smile, which led him to gradually move away from the project. Love has since defended his actions, elaborating that he was displaying uncertainty over the song's lyrics, worried whether they would be appreciated and understood by the fanbase the band had built their commercial standing upon. The surrealism and obtuseness of the lyrics had led Love to adopt the term "acid alliteration" when describing them. Despite these reservations, Love contributed vocals when asked and followed Brian's odd requests to engage in behavior such as acting as an animal on the floor while recording vocals. In the years following, Love has asserted that whatever misgivings he had toward Smile laid specifically toward some of the lyrics and not the music. Carl Wilson corroborated Love's statements in the 1990s, and also added that he himself personally loved the lyrics. In 2013, Al Jardine spoke on the matter: "He’s a big Chuck Berry fan and he loves those kind of lyrics. … Mike was always trying to pinpoint Van Dyke saying, 'What does that mean?' And he would go, 'I don't know, I was high' (laughs). Mike would go, 'That's disgusting, that doesn't make any sense.'"

In 1975, Derek Taylor told NME: "A key factor in the breakdown had to be the Beach Boys themselves, whose stubbornness by this time had seemingly twisted itself into a grim determination to undermine the very foundations of this 'new music' in order to get back to the old accepted, dumb formulas." Danny Hutton reflected in 2012 that during the sessions for Smile and Pet Sounds there was worry in the Beach Boys camp that they wouldn't be able to perform the songs live to a satisfactory degree, and that the provided lyrics were too discomforting to the band especially after having achieved relatively stable mainstream success. Other people who were present at the sessions—including David Anderle and Michael Vosse—have also reported that Smile vocal sessions had been tenuous between Brian, Parks, and the other Beach Boys, which was reported to have caused Brian "tremendous paranoia" knowing every studio visit would lead to an argument. It was reported that during this time, Brian had been forcibly assumed into a benefactor role for the band and his family, which added to his hesitancy in delivering a product that had the potential to be a great commercial failure. Accusations like these culminated in several publications between the late 1960s and early 1970s which reported that it was Love in particular who had issues with straying from the formulaic style of the Beach Boys earlier material. Love has hypothesized that his vocal opposition to those who supplied Brian with hard drugs caused those participants to start spinning the web that pinned him as the reason to why Smile was shelved, something he says was further perpetuated by writers who weren't there. He also stated that his criticism of the drug culture mostly stemmed from observing the detrimental effects it played on his cousins. In response, Parks has repeatedly accused Love of historical revisionism, believing that Love held hostility toward Brian and Smile, and that it was "the deciding factor" in the album's postponement. Reacting to promotion for the Beach Boys' 50th anniversary reunion and The Smile Sessions compilation in 2011, Parks released a statement on his website:

Certainly, I did walk away from Smile. … I comment only to combat any doubt that Mike Love delayed the release of Smile by 40 years purely out of a mislaid jealousy. Smile was an obviously good work. … Yet, revising facts isn't necessary for the progress of profit. I sure wish Brian were here to weigh in.

In the ensuing years, Brian has stated on several occasions that the other Beach Boys met Smile with huge disapproval, and that he was disappointed with their reactions. Other times, he has said that the group eventually grew to like the material as sessions progressed. In 1976, Brian corroborated that some group members were opposed to the recording of "Good Vibrations", but declined to name who specifically. In the 2000s, Brian named Love's opposition a contribution to the project's failure explaining, "He was disgusted with it, he said 'I'm disgusted with this,' he said this is nothing like anything like a surf song or a car song or any kinda Beach Boy-type of song. I said 'Mike. If you don't wanna grow, you shouldn't live.'" The group was filmed by CBS during December 15 vocal sessions for "Surf's Up" and "Wonderful" which were reported to have went "very badly." In reference to all of these claims, The Smile Sessions compiler Alan Boyd has noted that group opposition is not audible on the recordings he has heard.

Reappraisal

For many years after its shelving, Brian Wilson was terrified of Smile; repeatedly denouncing the album while associating its music with all of his failures. At various points, he considered the recordings "contrived with no soul," being imitations of Phil Spector without "getting anywhere near him," and "corny drug influenced music." Over the years, he gradually became more comfortable discussing the work. In 1993, Mike Love believed that Smile "would have been a great record," but in its unfinished state is "nothing, it's just fragments." In 2013, Jardine felt "There's performances we probably should have finished. I can't tell you exactly what they are, but that's the way I feel."

According to visual artist Jeremy Glogan: "Smile and conceptual art both emerged from the same Era. Each signaled a radical from what had preceded in popular music and art respectively, and each heralded a shift away from 'the art object', whether LP record or formal art object, as a definitive self-referential statement." Toop argued that attempts to complete Smile are "misguided", naming Smile a "labyrinth" which exists "in a memory house into which Wilson invited all those who could externalize its elements" notwithstanding the user's familiarity with the album's fragments. He then proposes the inquiry: "Can a song say it all, depth breadth and flow, break its banks in flood yet still be a song?" Freaky Trigger shared the same view, writing: "There is no ‘correct’ track sequence, there is no completed album, because Smile isn’t a linear progression of tracks. As a collection of modular melodic ideas it is by nature organic and resists being bookended." For a special Smile edition of the 33 1/3 book series, Luis Sanchez writes:

If the counterculture had suddenly made it possible for a generation of Americans to define themselves against their cultural inheritance, Brian and Parks weren't convinced. Their work spoke of an urge to explore their native culture not as outsiders, but to identify with it emphatically and see where it led them. If Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys were going to survive as the defining force of American pop music they were, Smile was a conscious attempt to rediscover the impulses and ideas that power American consciousness from the inside out. It was a collaboration that led to some incredible music, which, if it had been completed as an album and delivered to the public in 1966, might have had an incredible impact. Considering the material that does survive, on its own terms, we can try to understand why Smile remains vital, and why it still matters as music. Because what I hear isn't an attempt to trade one musical identity for another, or a descent into madness. What I hear is the sound of an artist working to win back the essence of sincerity that powered The Beach Boys' music from the very beginning, and to show that it had (and has) more stories to tell. ... The music appeals not through any kind of detached countercultural outlook, but by taking the best aspects of The Beach Boys' music–scope of studio production, vocal harmonies, a sense of possibility–and shifting in a way that makes them sound total, consummate, as if this music is the music Brian was meant to make. There is nothing phony or fawning about any of it.

It is widely believed that the release of Smile would have reformed the public perception of the Beach Boys. Pitchfork Media has described the album as a "rite of passage for students of pop music history," and adds "If you're wired a certain way, once you learn the Smile story, you long to hear the album that never was. It looms out there in imagination, an album that lends itself to storytelling and legend, like the aural equivalent of the Loch Ness Monster. … So you might start hunting down bootlegs, poring over the fragments, and finding competing edits and track sequences, which only feeds your desire to know what the 'real' Smile could have been." They also believed that the album could have dramatically veered the course of popular music history and speculated: "Perhaps we wouldn't be so monotheistic in our pop leanings, worshiping only at the Beatles' altar the way some do today." Paste Magazine suggested that Smile would have had a greater impact than the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), explaining: "There have been countless rock opera, art rock and prog rock projects, but most have merely dressed up mediocre rock 'n’ roll in the gowns of grandiosity. But Wilson used the moving parts and shifting textures of art music not to show off but to reflect adulthood's mixed emotions. He used the through-line of classical composition not to replace pop's intimacy but to reinforce it, linking one personal moment to the next." Brian Torff, referring to Smile's advanced structures, noted: "Here was a guy who could craft something that was almost symphonic. … Not many people had that craft in pop music at that time. … really expanding the boundaries of what rock and pop music could be." In 1999, Freaky Trigger wrote that the album was not "the best album ever," but that it is "astoundingly original" for being antithetical to contemporary rock music, and that the nature of its "twilight existence challenges the legitimacy of that legend of rock which puts Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band at its summit." It concludes that:

Smile is so attractive is because it's the tangible evidence of an alternative rock history which turned out differently ... None of which would matter a damn if the record was boring. It isn't ... The very idea of basing an album around laughter and good health seems cracked, naive and baffling, but that's what Smile allegedly is: a humour record. And given that every year the angst, contrariness and cynicism of rock’n’roll culture gets more tedious, more oppressive, maybe even more dangerous, the more people exposed to Wilson’s damaged but beautiful humanism the better.

Devoted to "new American music that is outside the commercial mainstream," online publication NewMusicBox took exception with Smile, with it being "an album recorded more than 45 years ago by one of the biggest (and most financially lucrative) musical acts of all time." It explained that: "Wilson’s experiments in 1966 and 1967 seem normative of the kinds of things most interesting musicians in any genre were up to at that point and even tamer than some of them. The blurring of boundaries between musical genres was pretty much commonplace at that time, as was the attitude, however real or imagined, that just about any musical undertaking was somehow an expansion beyond anything that had come before it," and that "the same pride of place in American music history held by other great innovators" such as Charles Ives, George Gershwin, John Cage, John Coltrane, and James Brown, would "probably" never include Smile. However, as it explains: "his has more to do with the vagaries of reception history than with actual history. For many people, the Beach Boys will always be perceived as a light-hearted party band that drooled over 'California Girls' while on a 'Surfing Safari'."

Tom Nolan wrote that Smile was "a step, not 'better than Sgt. Pepper'", and that "it was just so new. even in its raw form. It didn't even need lyrics." Williams felt necessary to point out, "You should not feel dumb if you don't enjoy it. It's not a work of genius. It's a passionate experiment that both succeeds and fails. As a failure, it's famous. Its success, now that we all can hear it, is likely to be much more modest." Smile is often compared by critics to works by other artists that have either remained unreleased or unfinished due to various circumstances. Similarly-fated albums include Charles Mingus' Epitaph, Brian Eno's My Squelchy Life, Mark Wirtz's A Teenage Opera, and The Who's Lifehouse project.

Cultural impact

—Robert SchneiderThe potential of what Smile would have been was the primary thing that inspired us (Elephant 6). When we started hearing Smile bootlegs, it was mind-blowing. It was what we had hoped it would be, but a lot of those songs weren't finished, so there was still this mystery of not hearing the melodies and lyrics. We wondered, "What are these songs and how do they fit together? Is this a verse?"

Various artists have cited Smile and its themes as a major influence. Kevin Shields of the Irish shoegaze band My Bloody Valentine has said that the 2013 album MBV was inspired by Smile, expounding "The idea was to bring a lot of parts together, riffs or chord changes without making a song out of it. … I wanted to see what would happen if I worked in a more impressionistic way, so that it only comes together at the end." Composers for the 1994 Super Nintendo role-playing video game EarthBound cited Smile and related work as major influences on the game's soundtrack. The Elephant 6 Recording Company, a collective of independent artists which include Apples in Stereo, the Olivia Tremor Control, Neutral Milk Hotel, Beulah, Elf Power, and Of Montreal, was founded through a mutual admiration of 1960s pop music, with Smile being "their Holy Grail". According to Kevin Barnes, of Montreal's album Coquelicot Asleep in the Poppies: A Variety of Whimsical Verse (2001) was partially based on Smile. The album Black Foliage: Animation Music Volume One (1999) by the Olivia Tremor Control has been compared to Smile for its dichotomous vocal harmony pop and avant-garde tape manipulation. It is reported that Lindsey Buckingham accessed Smile master tapes for research purposes during the making of Fleetwood Mac's Tusk (1979), and that the tracks "That's All For Everyone" and "Beautiful Child" most strongly exemplify the results. Domenic Priore believes that Smile influence is evident on the Flaming Lips' The Soft Bulletin (1999), Mercury Rev's All Is Dream (2001), the Apples in Stereo's Her Wallpaper Reverie (1999), Heavy Blinkers' 2000 eponymous LP, the Thrills' So Much for the City (2000), and XTC's Oranges & Lemons (1989).

Referring to a Smile track where "a whole bunch of tubas having a conversation with trumpets," Questlove of neo soul band the Roots said "'s a modern day Stravinsky … The way he constructs his music, he's a madman. … He was doing stuff that modern people do now, looping his work and stuff." Elvis Costello described a Smile piano demo of "Surf's Up" as akin to an original recording of Mozart in performance, and added "It's such an amazing tune. The words are very much of the time, they sound beautiful when they're sung—and quite of lot of that is true with the rest of the songs that come from this period, where obviously there was a stress and strain in realizing the music." Black Flag vocalist Henry Rollins has written enormous praise to Smile, calling the album "one of the best things you are likely to hear in all of your life. There are moments on Smile that are so astonishingly good you might find yourself just staring at your speakers in unguarded wonder, as I have." Don Was of Was (Not Was) has said, "In the fall of 1989, I was working with a band who turned me on to the bootlegged recordings of Brian Wilson's legendary, aborted Smile sessions. Like a musical burning bush, these tapes awakened me to a higher consciousness in record making. I was amazed that one, single human could dream up this unprecedented and radically advanced approach to rock 'n roll." Speaking about Smile, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins has said, "I really hear America. I really feel that he was trying to sum up America. He was literally trying to bring Mark Twain into rock and roll, and he almost got there." Power pop musician Matthew Sweet felt: "Van Dyke's lyrics are so cool and Brian did right by them. He and Brian are trying to capture an impressionistic thing. That time is so experimental, and looking at it now, it's easy to see why it could be overlooked — because people just don't instantly understand really abstract stuff. It takes time to have a conversation about it before we realize what an amazing thing they did."

Independent musicians and groups such as Ant-Bee, Melt-Banana, Jim O'Rourke, Adventures in Stereo, Rufus Wainwright, and Secret Chiefs 3 have all recorded cover versions of Smile tracks. Smiling Pets (1998) is a tribute album which largely focuses on various artists' interpretations of Smile-era recordings by the Beach Boys. In 1995, the Wondermints performed a live cover of "Surf's Up" at the Morgan-Wixon Theater in Los Angeles with Brian in the audience, who was then quoted saying "If I'd had these guys back in '66, I could've taken Smile on the road." Both albums Making God Smile: An Artists' Tribute to the Songs of Beach Boy Brian Wilson (2002) and Smiles, Vibes & Harmony: A Tribute to Brian Wilson (1990) features cover artwork reworked from the original Smile album artwork. The cover artwork for power pop band Velvet Crush's Teenage Symphonies to God (1994) was based on Frank Holmes' artwork for Smile. Dutch avant-garde group Palnickx paid homage to Smile on their 1996 rock-themed concept album The Psychedelic Years; the tracks "Phase Ten/Thirteen (Brian Wilson)" and "Phase Twelve (Fire/Rebuilding After the Fire)" feature multiple references to the project's themes, tracks, and legends. Weird Al Yankovic recorded a song on his 2006 album Straight Outta Lynwood modeled after Smile's aesthetic, entitled "Pancreas". Brian Wilson himself would later revisit Smile's themes and cut-up structure within his eponymous debut solo album Brian Wilson (1988), which features the eight-minute-long psychedelic western saga "Rio Grande".

Scenes from the films Grace of My Heart and Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story both feature homages to Smile. The latter contains the song "Black Sheep", a parody of Brian Wilson's music style composed by Van Dyke Parks. The albums sessions were dramatized in the made-for-television biopics Summer Dreams: The Story of the Beach Boys and The Beach Boys: An American Family. Portions of the Smile sessions will evidently also be dramatized in the upcoming Wilson biopic Love and Mercy, featuring Paul Dano as Brian Wilson and Max Schneider as Van Dyke Parks. The 1993 fiction novel Glimpses by Lewis Shiner contains a chapter in which the protagonist travels back in time to November 1966 and helps Wilson complete Smile. References to Smile, its bootlegs, and the Beach Boys are made in the 2006 novel Eat the Document by Dana Spiotta.

Legacy

Smiley Smile

Main article: Smiley SmileThe Beach Boys still needed to complete an LP record to fulfill their obligations to Capitol Records, so an album replacement was recorded throughout June and July. As Wilson retreated to his recently acquired Bel Air mansion, it became the venue for the recording of much of the Beach Boys' next album, Smiley Smile. Released that September, the album included newly stripped-down recordings of several Smile tracks. Besides its title and contents, the album was somewhat linked to Smile by carrying on the "humor" concept; much of the album is idiosyncratic, described by British rock journalist Nick Kent as "dumb pot-head skits, so-called healing chants and even some weird 'loony tunes' items straight out of a cut-rate Walt Disney soundtrack". Upon release, Smiley Smile was received with confusion by critics and was the group's lowest-selling album to date in the US, making only number 41 on the Billboard 200, although it fared considerably better in Britain, where it reached number nine on the album chart. The album was later described by brother and bandmate Carl Wilson as "a bunt instead of a grand slam".

Reconstructions

See also: 20/20 (The Beach Boys album), Surf's Up (album), and Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of The Beach BoysIn mid-June 1967, before the release of Smiley Smile, Capitol A&R director Karl Engemann began circulating a memo which discussed conversations between him and Wilson of a 10-track Smile album. It would have followed up the release of Smiley Smile, and would not have included the selections "Heroes and Villains" nor "Vegetables". During promotion for the June 24 release of the "Heroes and Villains" single, Bruce Johnston told NME that the Smile album was expected for release within two months. By July, the group's dispute with Capitol was resolved; it was then agreed that Smile would not be the band's next album. Carl Wilson would soon frequently revisit the session tapes, taking into mind the possibility of salvaging them for future release.

Problems playing this file? See media help.