| Revision as of 15:44, 11 December 2014 view sourceOmnipaedista (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers242,312 edits per MOS:DOB← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:06, 26 December 2014 view source OccultZone (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers224,089 edits fix CS1 errorNext edit → | ||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Spellberg|first1=Denise|author1-link=Denise Spellberg|title=Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: the Legacy of A'isha bint Abi Bakr|year=1994|publisher=]|isbn=978-0231079990|ref=harv}} | * {{cite book|last1=Spellberg|first1=Denise|author1-link=Denise Spellberg|title=Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: the Legacy of A'isha bint Abi Bakr|year=1994|publisher=]|isbn=978-0231079990|ref=harv}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Tabatabaei|first1=Muhammad Husayn|title=Shi'ite Islam|others=Translated by ]|language=Arabic|year=1979|publisher=]|isbn=0-87395-272-3|ref=harv}} | * {{cite book|last1=Tabatabaei|first1=Muhammad Husayn|title=Shi'ite Islam|others=Translated by ]|language=Arabic|year=1979|publisher=]|isbn=0-87395-272-3|ref=harv}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Vaglieri|first1=Laura Veccia|author1-link=Laura Veccia Vaglieri|title=The Cambridge History of Islam| editor1-first = Peter M. |editor-link1 = Peter M. Holt | editor2-last=Lambton|editor2-first=Ann|editor2-link=Ann Lambton|editor3-last =Lewis| editor3-first=Bernard| editor3-link = Bernard Lewis|year=1977|publisher=]|isbn=9781139055024|doi=10.1017/CHOL9780521219464|volume=1|chapter=4|ref=harv}} | * {{cite book|last1=Vaglieri|first1=Laura Veccia|author1-link=Laura Veccia Vaglieri|title=The Cambridge History of Islam| editor1-first = Peter M. |editor1-last = Holt|editor-link1 = Peter M. Holt | editor2-last=Lambton|editor2-first=Ann|editor2-link=Ann Lambton|editor3-last =Lewis| editor3-first=Bernard| editor3-link = Bernard Lewis|year=1977|publisher=]|isbn=9781139055024|doi=10.1017/CHOL9780521219464|volume=1|chapter=4|ref=harv}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Watt|first1=William Montgomery|author1-link=William Montgomery Watt|title=ʿĀʾis̲h̲a Bint Abī Bakr|url=http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/aisha-bint-abi-bakr-SIM_0440|year=1960|publisher=] Online|isbn=9789004161214|edition=2nd|accessdate=26 February 2014|ref=harv}} | * {{cite book|last1=Watt|first1=William Montgomery|author1-link=William Montgomery Watt|title=ʿĀʾis̲h̲a Bint Abī Bakr|url=http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/aisha-bint-abi-bakr-SIM_0440|year=1960|publisher=] Online|isbn=9789004161214|edition=2nd|accessdate=26 February 2014|ref=harv}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Watt|first1=William Montgomery|author1-link=William Montgomery Watt|title=Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman |year=1961|publisher=]|isbn=978-0198810780|ref=harv}} | * {{cite book|last1=Watt|first1=William Montgomery|author1-link=William Montgomery Watt|title=Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman |year=1961|publisher=]|isbn=978-0198810780|ref=harv}} | ||

Revision as of 07:06, 26 December 2014

For other uses, see Aisha (disambiguation).

| Wives of Muhammad | ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| Mother of the BelieversAisha | |

|---|---|

| (Arabic): عائشة | |

| Born | ‘Ā’ishah bint Abī Bakr c. 613/614 CE Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia (present-day Saudi Arabia) |

| Died | July 16, 678 (aged 64) Medina, Hejaz, Arabia (present-day Saudi Arabia) |

| Resting place | Jannat al-Baqi, Medina, Hejaz, Arabia (present-day Saudi Arabia) |

| Spouse(s) | Muhammad (m. 619-June 8, 632) |

| Parent(s) | Abu Bakr (father) Umm Ruman (mother) |

| Military career | |

| Battles / wars | First Fitna |

‘Ā’ishah bint Abī Bakr (613/614 – 678 CE) (Template:Lang-ar transliteration: ‘Ā’ishah, Template:IPA-ar, also transcribed as A'ishah, Aisyah, Ayesha, A'isha, Aishat, Aishah, or Aisha) was one of Muhammad's wives. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" (Arabic: أمّ المؤمنين umm al-mu'minīn), per the description of Muhammad's wives in the Quran.

The majority of traditional hadith sources state that Aisha was married to Muhammad at the age of six or seven, but she stayed in her parents' home until the age of nine, or ten according to Ibn Hisham, when the marriage was consummated with Muhammad, then 53, in Medina;

Aisha had an important role in early Islamic history, both during Muhammad's life and after his death. In Sunni tradition, Aisha is thought to be scholarly and inquisitive. She contributed to the spread of Muhammad's message and served the Muslim community for 44 years after his death. She is also known for narrating 2210 hadiths, not just on matters related to the Prophet's private life, but also on topics such inheritance, pilgrimage, and eschatology. Her intellect and knowledge in various subjects, including poetry and medicine, were highly praised by early luminaries such as al-Zuhri and her student Urwa ibn al-Zubayr.

Her father, Abu Bakr, became the first caliph to succeed Muhammad, and after two years was succeeded by Umar. During the time of the third caliph Uthman, Aisha had a leading part in the opposition that grew against him, though she did not agree either with those responsible for his assassination nor with the party of Ali. During the reign of Ali, she wanted to avenge Uthman's death, which she attempted to do in the Battle of the Camel. She participated in the battle by giving speeches and leading troops on the back of her camel. She ended up losing the battle, but her involvement and determination left a lasting impression. Afterwards, she lived quietly in Medina for more than twenty years, took no part in politics, and became reconciled to Ali and did not oppose Mu'awiya.

Early life

Aisha was born in late 613 or early 614 She was the daughter of Umm Ruman and Abu Bakr of Mecca, two of the Muhammad's most trusted companions. Aisha was the third and youngest wife of Muhammad.

Marriage to Muhammad

The idea to match Aisha with Muhammad was suggested by Khawlah bint Hakim. After this, the previous agreement regarding the marriage of Aisha with Jubayr ibn Mut'im was put aside by common consent. Abu Bakr was uncertain at first "as to the propriety or even legality of marrying his daughter to his "brother." " British historian William Montgomery Watt suggests that Muhammad hoped to strengthen his ties with Abu Bakr; the strengthening of ties commonly served as a basis for marriage in Arabian culture.

Age at marriage

See also: Criticism of Muhammad (Aisha) and Child marriageAccording to Sunni scriptural Hadith sources, Aisha was six or seven years old when she was married to Muhammad and nine when the marriage was consummated. For example, Sahih al-Bukhari, considered by many Sunni Muslims as the most authentic book after Quran, states:

Narrated 'Aisha: that the Prophet married her when she was six years old and he consummated his marriage when she was nine years old, and then she remained with him for nine years (i.e., till his death).

— Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:62:64

Some traditional sources disagree. Ibn Hisham wrote in his biography of Muhammad that she may have been ten years old at the consummation. Ibn Khallikan, as well as Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi citing Hisham ibn Urwah, record that she was nine years old at marriage, and twelve at consummation.

In the twentieth century, Pakistani writer Muhammad Ali of the Ahmadiyya minority sect of Islam, challenged the Sahih al-Bukhari. He acknowledged that Aisha was young as the traditional sources claim; but argued that instead a new interpretation of the Hadith compiled by Mishkat al-Masabih, Wali-ud-Din Muhammad ibn Abdullah Al-Khatib, could indicate that Aisha would have been nineteen years old around the time of her marriage. However, the hadith compiled by Mishkat al-Masabih is not a Ṣaḥīḥ (صَحِيْح) hadith, and its authenticity is considered doubtful by many scholars such as al-Tabrizi.

No sources offer much more information about Aisha's childhood years. Child marriage was not uncommon in many places at the time, Arabia included. It often served political purposes, and Aisha's marriage to Muhammad would have had a political connotation.

Aisha's age at the time she was married to Muhammad has been of interest since the earliest days of Islam, and references to her age by early historians are frequent. American historian Denise Spellberg has reviewed Islamic literature on Aisha's virginity, age at marriage and age when the marriage was consummated. Spellberg states, "Aisha's age is a major pre-occupation in Ibn Sa'd where her marriage varies between six and seven; nine seems constant as her age at the marriage's consummation." She notes one exception in Ibn Hisham's biography of the Prophet, which suggests the age of consummation may have been when Aisha was age 10, summarizing her review with the note that "these specific references to the bride's age reinforce Aisha's pre-menarcheal status and, implicitly, her virginity. They also suggest the variability of Aisha's age in the historical record." Early Muslims regarded Aisha's youth as demonstrating her virginity and therefore her suitability as a bride of Muhammad. This issue of her virginity was of great importance to those who supported Aisha's position in the debate of the succession to Muhammad. These supporters considered that as Muhammad's only virgin wife, Aisha was divinely intended for him, and therefore the most credible regarding the debate.

Personal life

Relationship with Muhammad

In many Muslim traditions, Aisha is described as Muhammad's most beloved or favored wife after his first wife, Khadija bint Khuwaylid, who died before the migration to Medina took place. There are several hadiths, or stories or sayings of Muhammad, that support this belief. One relates that when a companion asked Muhammad, "who is the person you love most in the world?" he responded, "Aisha." Others relate that Muhammad built Aisha’s apartment so that her door opened directly into the mosque, and that she was the only woman with whom Muhammad received revelations. They bathed in the same water and he prayed while she lay stretched out in front of him.

There are also various traditions that reveal the mutual affection between Muhammad and Aisha. He would often just sit and watch her and her friends play with dolls, and on occasion he would even join them. Additionally, they were close enough that each was able to discern the mood of the other, as many stories relate. It is also important to note that there exists evidence that Muhammad did not view himself as entirely superior to Aisha, at least not enough to prevent Aisha from speaking her mind, even at the risk of angering Muhammad. On one such instance, Muhammad's "announcement of a revelation permitting him to enter into marriages disallowed to other men drew from her the retort, 'It seems to me your Lord hastens to satisfy your desire!'" Furthermore, Muhammad and Aisha had a strong intellectual relationship. Muhammad valued her keen memory and intelligence and so instructed his companions to draw some of their religious practices from her.

Accusation of adultery

The story of accusation of adultery levied against Aisha can be traced to sura (chapter) An-Nur of the Quran. As the story goes, Aisha left her howdah in order to search for a missing necklace. Her slaves mounted the howdah and prepared it for travel without noticing any difference in weight without Aisha's presence. Hence the caravan accidentally departed without her. She remained at the camp until the next morning, when Safwan bin al-Mu‘attal, a nomad and member of Muhammad's army, found her and brought her back to Muhammad at the army's next camp. Rumours that Aisha and Safwan had committed adultery were spread, particularly by Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy, Hassan ibn Thabit, Mistah ibn Uthatha and Hammanah bint Jahsh (sister of Zaynab bint Jahsh, another of Muhammad's wives). Usama ibn Zayd, son of Zayd ibn Harithah, defended Aisha's reputation, but Ali recommended that he divorce her. Muhammad came to speak directly with Aisha about the rumours. He was still sitting in her house when he announced that he had received a revelation from God confirming Aisha's innocence. Surah 24 details the Islamic laws and punishment regarding adultery and slander. Aisha's accusers were subjected to punishments of 80 lashes.

Story of the honey

After the daily Asr prayer, Muhammad would visit each of his wives' apartments to inquire about their well-being. Muhammad was just in the amount of time he spent with them and attention he gave to them. Once, Muhammad's fifth wife, Zaynab bint Jahsh, received some honey from a relative which Muhammad took a particular liking to. As a result, every time Zaynab offered some of this honey to him he would spend a longer time in her apartment. This did not sit well with Aisha and Hafsa bint Umar.

Hafsa and I decided that when the Prophet entered upon either of us, she would say, "I smell in you the bad smell of Maghafir (a bad smelling raisin). Have you eaten Maghafir?" When he entered upon one of us, she said that to him. He replied (to her), "No, but I have drunk honey in the house of Zainab bint Jahsh, and I will never drink it again."..."But I have drunk honey." Hisham said: It also meant his saying, "I will not drink anymore, and I have taken an oath, so do not inform anybody of that'

— Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari

Soon after this event, Muhammad reported that he had received a revelation in which he was told that he could eat anything permitted by God. Some Sunni commentators on the Quran sometimes give this story as the "occasion of revelation" for At-Tahrim, which opens with the following verses:

O Prophet! Why holdest thou to be forbidden that which Allah has made lawful to thee? Thou seekest to please thy consorts. But Allah is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful.

— Quran, surah 66 (At-Tahrim), ayat 1-2

Allah has already ordained for you, (O men), the dissolution of your oaths (in some cases): and Allah is your Protector, and He is Full of Knowledge and Wisdom.

Word spread to the small Muslim community that Muhammad's wives were speaking sharply to him and conspiring against him. Muhammad, saddened and upset, separated from his wives for a month. ‘Umar, Hafsa's father, scolded his daughter and also spoke to Muhammad of the matter. By the end of this time, his wives were humbled; they agreed to "speak correct and courteous words" and to focus on the afterlife.

Death of Muhammad

Aisha remained Muhammad's favorite wife throughout his life. When he became ill and suspected that he was probably going to die, he began to ask his wives whose apartment he was to stay in next. They eventually figured out that he was trying to determine when he was due with Aisha, and they then allowed him to retire there. He remained in Aisha's apartment until his death, and his last breath was taken as he lay in the arms of Aisha, his most beloved wife.

Political career

After Muhammad's death, which ended Aisha and Muhammad's 9 year-long marriage, Aisha lived fifty more years in and around Medina. Much of her time was spent learning and acquiring knowledge of the Quran and the sunnah of Muhammad. Aisha was one of three wives (the other two being Hafsa bint Umar and Umm Salama) who memorized the Quran. Like Hafsa, Aisha had her own script of the Quran written after Muhammad's death. During Aisha's life many prominent customs of Islam, such as veiling and seclusion of women, began.

Aisha's importance to revitalizing the Arab tradition and leadership among the Arab women highlights her magnitude within Islam. Aisha became involved in the politics of early Islam and the first three caliphate reigns: Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, and ‘Uthman. During a time in Islam when women were not expected, or wanted, to contribute outside of the household, Aisha delivered public speeches, became directly involved in war and even battles, and helped both men and women to understand the practices of Muhammad.

Role during caliphate

Role during first and second caliphates

After Muhammad's death in 632, Abu Bakr was appointed as the first caliph. This matter of succession to Muhammad is extremely controversial to the Shia who believe that Ali had been appointed by Muhammad to lead while Sunni maintain that the public elected Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr had two advantages in achieving his new role: his long personal friendship with Muhammad and his role as father-in-law. As caliph, Abu Bakr was the first to set guidelines for the new position of authority.

Aisha garnered more special privilege in the Islamic community for being known as both a wife of Muhammad and the daughter of the first caliph. Being the daughter of Abu Bakr tied Aisha to honorable titles earned from her father's strong dedication to Islam. For example, she was given the title of al-siddiqa bint al-siddiq, meaning 'the truthful woman, daughter of the truthful man', a reference to Abu Bakr's support of the Isra and Mi'raj.

In 634 Abu Bakr fell sick and was unable to recover. Prior to his death, he appointed ‘Umar, one of his chief advisers, as the second caliph Throughout ‘Umar's time in power Aisha continued to play the role of a consultant in political matters.

Role during the third caliphate

After ‘Umar died, ‘Uthmān was chosen to be the third caliph. He wanted to promote the interests of the Umayyads. Aisha had little involvement with ‘Uthmān for the first couple years, but eventually she found a way into the politics of his reign. She eventually grew to despise ‘Uthmān, and many are unsure of what specifically triggered her eventual opposition towards him. A prominent opposition that arose towards him was when ‘Uthmān mistreated ‘Ammar ibn Yasir (companion of Muhammad) by beating him. Aisha became enraged and spoke out publicly, saying, "How soon indeed you have forgotten the practice (sunnah) of your prophet and these, his hairs, a shirt, and sandal have not yet perished!".

As time continued issues of antipathy towards ‘Uthmān continued to arise. Another instance of opposition arose when the people came to Aisha, after Uthmān ignored the rightful punishment for Walid idn Uqbah (Uthmān's brother). Aisha and Uthmān argued with each other, Uthmān eventually made a comment on why Aisha had come and how she was "ordered to stay at home". Arising from this comment, was the question of whether Aisha, and for that matter women, still had the ability to be involved in public affairs. The Muslim community became split: "some sided with Uthmān, but others demanded to know who indeed had better right than Aisha in such matters".

The caliphate took a turn for the worse when Egypt was governed by Abdullah ibn Saad. Abbott reports that Muhammad ibn Abi Hudhayfa of Egypt, an opponent of ‘Uthmān, forged letters in the Mothers of the Believers' names to the conspirators against ‘Uthmān. The people cut off ‘Uthmān's water and food supply. When Aisha realized the behavior of the crowd, Abbott notes, Aisha could not believe the crowd "would offer such indignities to a widow of Mohammad". This refers to when Safiyya bint Huyayy (one of Muhammad's wives) tried to help ‘Uthmān and was taken by the crowd. Malik al-Ashtar then approached her about killing Uthmān and the letter, and she claimed she would never want to "command the shedding of the blood of the Muslims and the killing of their Imām"; she also claimed she did not write the letters. The city continued to oppose ‘Uthmān, but as for Aisha, her journey to Mecca was approaching. With the journey to Mecca approaching at this time, she wanted to rid herself of the situation. ‘Uthmān heard of her not wanting to hurt him, and he asked her to stay because of her influence on the people, but this did not persuade Aisha, and she continued on her journey.

First Fitna

Main article: Battle of the Camel

Abu Bakr's reign was short, and in 634 he was succeeded by Umar as caliph. Umar reigned for ten years before being assassinated and was followed by Uthman ibn Affan in 644. Both of these men had been among Muhammad's earliest followers, were linked to him by clanship and marriage, and had taken prominent parts in various military campaigns. Aisha, in the meantime, lived in Medina and made several pilgrimages to Mecca.

In 655, Uthman's house was put under siege by about 1000 rebels. Eventually the rebels broke into the house and murdered Uthman, provoking the First Fitna. After killing Uthman, the rebels asked Ali to be the new caliph, although Ali was not involved in the murder of Uthman according to many reports. Ali reportedly initially refused the caliphate, agreeing to rule only after his followers persisted.

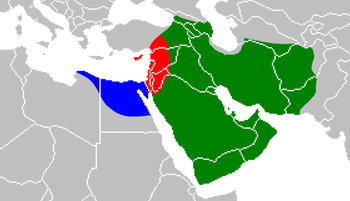

When Ali could not execute those merely accused of Uthman's murder, Aisha delivered a fiery speech against him for not avenging the death of Uthman. The first to respond to Aisha was Abdullah ibn Aamar al-Hadhrami, the governor of Mecca during the reign of Uthman, and prominent members of the Banu Umayya. With the funds from the "Yemeni Treasury" Aisha set out on a campaign against the Rashidun Caliphate of Ali.

Aisha, along with an army including Zubayr ibn al-Awam and Talha ibn Ubayd-Allah, confronted Ali's army, demanding the prosecution of Uthman's killers who had mingled with his army outside the city of Basra. When her forces captured Basra she ordered the execution of 600 Muslims and 40 others, including Hakim ibn Jabala, who were put to death in the Grand Mosque of Basra. Aisha's forces are also known to have tortured and imprisoned Othman ibn Hanif the governor of Basra appointed by Ali.

Ali rallied supporters and fought Aisha's forces near Basra in 656. The battle is known as the Battle of the Camel, after the fact that Aisha directed her forces from a howdah on the back of a large camel. Aisha's forces were defeated and an estimated 10,000 Muslims were killed in the battle, considered the first engagement where Muslims fought Muslims.

After 110 days of conflict the Rashidun Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib met Aisha with reconciliation. He sent her back to Medina under military escort headed by her brother Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, one of Ali's commanders. She subsequently retired to Medina with no more interference with the affairs of state she was also awarded a pension by Ali.

Although she retired to Medina her forsaken efforts against the Rashidun Caliphate of Ali did not end the First Fitna.

Contributions to Islam and influence

After 25 years of a monogamous relationship with his first wife, Khadija bint Khuwaylid, Muhammad participated in nine years of polygyny, marrying at least nine further wives. Muhammad's subsequent marriages were depicted purely as political matches rather than unions of sexual indulgence. In particular, Muhammad's unions with Aisha and Hafsa bint Umar associated him with two of the most significant leaders of the early Muslim community, Aisha's and Hafsa's fathers, Abu Bakr and ‘Umar ibn al-Khattāb, respectively.

Aisha's marriage has given her significance among many within Islamic culture, becoming known as the most learned woman of her time. Being Muhammad's favorite wife, Aisha occupied an important position in his life. When Muhammad married Aisha in her youth, she was accessible "...to the values needed to lead and influence the sisterhood of Muslim women." After the death of Muhammad, Aisha was discovered to be a renowned source of hadiths, due to her qualities of intelligence and memory. Aisha conveyed ideas expressing Muhammad's practice (sunnah). She expressed herself as a role model to women, which can also be seen within some traditions attributed to her. The traditions regarding Aisha habitually opposed ideas unfavorable to women in efforts to elicit social change.

Muhammad became a significantly powerful figure of the rapidly expanding Islamic community in 627 Due to this expansion, segregation of his wives was permitted to enforce their sacrosanct status.

According to Reza Aslan:

The so-called Muslim women’s movement is predicated on the idea that Muslim men, not Islam, have been responsible for the suppression of women’s rights. For this reason, Muslim feminists throughout the world are advocating a return to the society Muhammad originally envisioned for his followers. Despite differences in culture, nationalities, and beliefs, these women believe that the lesson to be learned from Muhammad in Medina is that Islam is above all an egalitarian religion. Their Medina is a society in which Muhammad designated women like Umm Waraqa as spiritual guides for the Ummah; in which the Prophet himself was sometimes publicly rebuked by his wives; in which women prayed and fought alongside the men; in which women like Aisha and Umm Salamah acted not only as religious but also as political—and on at least one occasion military—leaders; and in which the call to gather for prayer, bellowed from the rooftop of Muhammad’s house, brought men and women together to kneel side by side and be blessed as a single undivided community.

Aisha played a key role in the emergence of Islam, and played an active position in social reform of the Islamic culture. Not only was she supportive of Muhammad, but she contributed scholarly intellect to the development of Islam. She was given the title al-Siddiqah, meaning 'the one who affirms the truth'. Aisha was known for her "...expertise in the Quran, shares of inheritance, lawful and unlawful matters, poetry, Arabic literature, Arab history, genealogy, and general medicine." Her intellectual contributions regarding the verbal texts of Islam were in time transcribed into written form, becoming the official history of Islam. After the death of Muhammad, Aisha was regarded as the most reliable source in the teachings of hadith. As she was Muhammad's favorite wife and a close companion, soon after his death the Islamic community began consulting Aisha on Muhammad's practices, and she was often used to settle disputes on demeanor and various points of law. Aisha's authentication of Muhammad's ways of prayer and his recitation of the Quran allowed for development of knowledge of his sunnah of praying and reading verses of the Quran.

During Aisha's entire life she was a strong advocate for the education of Islamic women, especially in law and the teachings of Islam. She was known for establishing the first madrasa for women in her home. Attending Aisha's classes were various family relatives and orphaned children. Men also attended Aisha's classes, with a simple curtain separating the male and female students.

Political influence

As mentioned before, Aisha became an influential figure in early Islam after Muhammad's death. However, Aisha also had a strong political influence. Though Muhammad had ordered his wives to stay in the home, Aisha, after Muhammad's death, took a public and predominant role in politics. Some say that Aisha's political influence helped promote her father, Abu Bakr, to the caliphate after Muhammad's death.

After the defeat at the Battle of the Camel, Aisha retreated to Medina and became a teacher. Upon her arrival in Medina, Aisha retired from her public role in politics. Her discontinuation of public politics, however, did not stop her political influence completely. Privately, Aisha continued influencing those intertwined in the Islamic political sphere. Amongst the Islamic community, she was known as an intelligent woman who debated law with male companions. Aisha was also considered to be the embodiment of proper rituals while partaking in the pilgrimage to Mecca, a journey she made with several groups of women. For the last two years of her life, Aisha spent much of her time telling the stories of Muhammad, hoping to correct false passages that had become influential in formulating Islamic law. Due to this, Aisha's political influence continues to impact those in Islam.

Death

Aisha died of disease at her home in Medina on 17 Ramadan 58 AH (16 July 678). She was 64 years old. Muhammad's companion Abu Hurairah led her funeral prayer after the tahajjud (night) prayer, and she was buried at Jannat al-Baqi‘.

Views

Sunni view of Aisha

Sunnis believe she was Muhammad's favorite wife. They consider her (among other wives) to be Umm al-Mu’minin and among the members of the Ahl al-Bayt, or Muhammad's family.

Shia view of Aisha

Main article: Shia view of AishaThe Shia view Aisha negatively. They accuse her of hating Ali and defying him during his caliphate in the Battle of the Camel, when she fought men from Ali's army in Basra.

See also

Notes

- ^ Al-Nasa'i 1997, p. 108

‘A’isha was eighteen years of age at the time when the Holy Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) died and she remained a widow for forty-eight years till she died at the age of sixty-seven. She saw the rules of four caliphs in her lifetime. She died in Ramadan 58 AH during the caliphate of Mu‘awiya...

- ^ Spellberg 1994, p. 3

- Quran 33:6

- Brockelmann 1947

- ^ Abbott 1942

- ^ Spellberg 1994, pp. 39–40

- ^ Armstrong 1992, p. 157

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:234, 5:58:236, 7:62:64, 7:62:65, 7:62:88, Sahih Muslim, 8:3309, 8:3310, 8:3311, 41:4915, Sunan Abu Dawood, 41:4917

- ^ al-Tabari 1987, p. 7, al-Tabari 1990, p. 131

- Aleem, Shamim (2007). Prophet Muhammad(s) and His Family: A Sociological Perspective. AuthorHouse. p. 130. ISBN 9781434323576.

- Islamyat: a core text for students

- ^ Sayeed, Asma (2013-08-06). Women and the Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–9. ISBN 9781107031586.

- ^ Watt 1960

- Abbott 1942, p. 1

- Ibn Sa'd 1995, p. 55

i.e., the year 613-614Aisha was born at the beginning of the fourth year of prophethood

- ^ Esposito

- Ahmed 1992

- ^ Abbott 1942, p. 3

- Sonbol 2003, pp. 3–9 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSonbol2003 (help)

- Barlas 2002, pp. 125–126

- ^ Afsaruddin 2014: "according to the chronology of Ibn Khallikān (d. 681/1282) she would have been nine at her marriage and twelve at its consummation (Wafayāt al-aʿyān, 3:16), a chronology also supported by a report from Hishām b. ʿUrwa recorded by Ibn Saʿd (d. 230/845; al-Ṭabaqāt, 8:61)."

- Ali 1997, p. 150

- James Robson (1964), Mishkat al-Masabih, S. M. Ashraf, OCLC 500616691

- Juan Campo, Encyclopedia of Islam, ISBN 978-0816077458

- Watt 1961, p. 102

- Abbott 1942, p. 7

- Spellberg 1994, pp. 34–40

- ^ Ahmed 1992, p. 51

- Roded 1994, p. 36

- Roded 2008, p. 23

- Joseph 2007, p. 227

- McAuliffe 2001, p. 55

- Mernissi 1988, p. 65

- Mernissi 1988, p. 107

- Abbott 1942, p. 25

- Roded 1994, p. 28

- Abbott 1942, p. 46

- Shaikh 2003, p. 33

- Abbott 1942, p. 8

- Lings 1983, pp. 133–134

- Haykal 1976, pp. 183–184

- Abbott 1942, pp. 67–68

- Lings 1983, p. 371

- Ahmed 1992, pp. 51–52

- Mernissi 1988, p. 104

- Mernissi 1988, p. 78

- The story is told multiple times in the early traditions, nearly all of the versions being ultimately derived from Aisha's own account. Typical examples can be found in Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:59:462, Sahih Muslim, 37:6673 and Guillaume 1955, pp. 494–499 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuillaume1955 (help).

- Great Women of Islam - Zaynab bint Jahsh

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 8:78:682

- Quran 66:1–2

- Ibn Sa'd 1995, pp. 132–133

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 3:43:648

- Ahmed 1992, p. 58

- Abbott 1942, p. 69

- Lings 1983, p. 339

- Haykal 1976, pp. 502–503

- Guillaume 1955, p. 679 and 682 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuillaume1955 (help)

- "Aishah bint Abu Bakr". Jannah.org. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ^ Elsadda 2001, pp. 37–64

- Spellberg & Aghaie, pp. 42–47 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSpellbergAghaie (help)

- Spellberg 1994, pp. 4–5

- Spellberg 1994, p. 33

- Abbott 1942, p. 108

- ^ Abbott 1942, p. 111

- ^ Abbott 1942, p. 122

- Abbott 1942, p. 123

- See:

- Lapidus 2002, p. 47

- Holt 1977, pp. 70–72 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHolt1977 (help)

- Tabatabaei 1979, pp. 50–57

- al-Athir 1231, p. 19P.19

- Holt 1977, pp. 67–68 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHolt1977 (help)

- Madelung 1997, p. 107 and 111

- "Khalifa Ali bin Abu Talib - Ayesha's Occupation of Basra (Hakim b Jabala)". Alim.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ishaq, Mohammad. Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. 3 (Part 1).

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Razwy 2001

- "Khalifa Ali bin Abu Talib - Ayesha's Occupation of Basra (War in Basra)". Alim.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Glubb 1963, p. 320

- Goodwin 1994

- Muir 1892, p. 261

- Black 1994, p. 34

- Aslan 2005, pp. 58–136

- ^ Anwar, Jawed (April 4, 2005). "History Shows the Importance of Women in Muslim Life". Muslims Weekly. Pacific News Service. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- Geissinger 2011, pp. 37–49

- Aslan 2005, p. 136

- Ahmed 1992, pp. 47–75

- Geissinger 2011, p. 42

- Ibn Kathir, p. 97

- "Objections to the Shia criticisms leveled at Ayesha". Shiapen.com. 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

References

- Abbott, Nabia (1942). Aishah The Beloved of Muhammad. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-405-05318-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Afsaruddin, Asma (2014). "ʿĀʾisha bt. Abī Bakr". In Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3 ed.). Brill Online. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Aghaie, Kamran Scot (Winter 2005). "The Origins of the Sunnite-Shiite Divide and the Emergence of the Ta'ziyeh Tradition". TDR: the Drama Review. 49 (4 (T188)). MIT Press: 42. doi:10.1162/105420405774763032.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300055832.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - al-Athir, Ali ibn (1231). The Complete History. Vol. 2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Al-Nasa'i (1997). Al-Sunan al-Sughra (in Arabic). Vol. 1. Translated by Muhammad Iqbal Siddiqi. Kazi Publications. ISBN 978-0933511446.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - al-Tabari. Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)- al-Tabari (1987). The Foundation of The Community (PDF) (in Arabic). Vol. 7. Translated by William Montgomery Watt and M. V. McDonald. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-344-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - al-Tabari (1990). The Last Years of the Prophet (PDF) (in Arabic). Vol. 9. Translated by Ismail Poonawala. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-691-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- al-Tabari (1987). The Foundation of The Community (PDF) (in Arabic). Vol. 7. Translated by William Montgomery Watt and M. V. McDonald. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-344-2.

- Ali, Muhammad (1997). Muhammad the Prophet. Ahamadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam. ISBN 978-0913321072.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Amira, Sonbol (2003). "Rise of Islam: 6th to 9th century". In Joseph, Suad (ed.). Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures. Vol. 1. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004113800.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Armstrong, Karen (1992). Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-250014-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aslan, Reza (2005). No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-73975-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barlas, Asma (2002). Believing Women in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qur'an. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70904-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, Edwin (1994). Banking on Baghdad: Inside Iraq's 7,000-year History of War, Profit, and Conflict. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0914153122. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brockelmann, Carl (1947). Geschichte der Islamischen Volker und Staaten (in German). Translated by Joel Carmichael and Moshe Perlmann. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Elsadda, Hoda (Spring 2001). "Discourses on Women's Biographies and Cultural Identity: Twentieth-Century Representations of the Life of 'A'isha Bint Abi Bakr". Feminist Studies. 27 (1). Feminist Studies, Inc. JSTOR 3178448.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Esposito, John L. "A'ishah In the Islamic World: Past and Present". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Geissinger, Aisha (January 2011). "'A'isha bint Abi Bakr and her Contributions to the Formation of the Islamic Tradition". Religion Compass. 5 (1). Blackwell Publishingdoi=10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00260.x: 37. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00260.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Glubb, John Bagot (1963). The Great Arab Conquests. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340009383.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goodwin, Jan (1994). Price of Honor: Muslim Women Lift the Veil of Silence on the Islamic World. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0452283770.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (1976). The Life of Muhammad (in Arabic). Translated by Isma'il Ragi Al-Faruqi. North American Trust Publications. ISBN 978-0892591374.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ibn Ishaq (1955). Sirat Rasul Allah (in Arabic). Translated by Alfred Guillaume. Oxford University. ISBN 0-19-636034-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Ibn Kathir. "book 4, chapter 7". Al-Bidaya wa'l-Nihaya (in Arabic).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Ibn Sa'd (1995). Women of Madina (in Arabic). Vol. 8. Translated by Aisha Bewley. Ta-Ha Publishers. ISBN 978-1897940242.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lapidus, Ira M. (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lings, Martin (1983). Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources. Inner Traditions International. ISBN 978-1594771538.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521646963.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (2001). Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. Vol. 1. Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-14743-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mernissi, Fatema (1988). Le Harem Politique (in French). Translated by Mary Jo Lakeland. Perseus Books Publishing. ISBN 9780201632217.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Muir, William (1892). The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline And Fall from Original Sources. The Religious Tract Society.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Razwy, Ali Ashgar (2001). "The Battle of Basra (the battle of Camel)". A Restatement of the History of Islam and Muslims. World Federation of Khoja Shia Ithna-Asheri Muslim Communities. ISBN 0950987913.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Roded, Ruth (1994). Women in Islamic Biographical Collections: From Ibn Sa'd to Who's Who. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1555874421.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roded, Ruth (2008). Women in Islam and the Middle East: A Reader. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1845113858.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shaikh, Sa‘diyya (2003). Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028656038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spellberg, Denise (1994). Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: the Legacy of A'isha bint Abi Bakr. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231079990.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tabatabaei, Muhammad Husayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam (in Arabic). Translated by Hossein Nasr. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vaglieri, Laura Veccia (1977). "4". In Holt, Peter M.; Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard (eds.). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521219464. ISBN 9781139055024.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watt, William Montgomery (1960). ʿĀʾis̲h̲a Bint Abī Bakr (2nd ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. ISBN 9789004161214. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watt, William Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198810780.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Joseph, Suad, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Volume 5 Practices, Interpretations and Representations. Brill Online. ISBN 9789004132474.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Afshar, Haleh, Democracy and Islam, Hansard Society, 2006.

- Rodinson, Maxime, Muhammad, 1980 Random House reprint of English translation

- Aisha bint Abi Bakr, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, 2000

- Rizvi, Sa'id Akhtar, The Life of Muhammad The Prophet, Darul Tabligh North America, 1971.

- Askri, Mortaza, 'Role of Ayesha in the History of Islam' (Translation), Ansarian publication, Iran

- Chavel, Geneviève. Aïcha : La bien-aimée du prophète. Editions SW Télémaque. 11 October 2007. ISBN 978-2753300552

External links

- Archived 2008-02-01 at the Wayback Machine