| Revision as of 13:45, 5 January 2015 editEpicgenius (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, IP block exemptions, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers331,109 editsm date formats per MOS:DATEFORMAT← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:49, 5 January 2015 edit undoDr. Blofeld (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors636,308 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

| The new building opened on Park Avenue, between East 49th and East 50th streets, 1 October 1931. It was the tallest and largest hotel in the world at the time,{{sfn|Korom|2008|p=422}} covering the entire block. The slender central tower became known as the '''Waldorf Towers''', with its own private entrance on 50th Street, and consisted of 100 suites, about one third of which were leased as private residences.{{sfn|Morrison|2014|p=105}} President ] said on the radio, broadcast from the ]: "The opening of the new Waldorf Astoria is an event in the advancement of hotels, even in New York City. It carries great tradition in national hospitality...marks the measure of nation's growth in power, in comfort and in artistry...an exhibition of courage and confidence to the whole nation..."<ref name="history"/> ] managed the hotel in the 1930s and 1940s, a commanding figure who Tony Rey referred to as "the greatest hotelman of his era".{{sfn|Morehouse III|1991|p=40}} Boomer was elected chairman of the board of the Waldorf-Astoria Corporation on 20 February 1945, a position he held until his death in a plane crash in July 1947.{{sfn|Morehouse III|1991|p=46-7}} | The new building opened on Park Avenue, between East 49th and East 50th streets, 1 October 1931. It was the tallest and largest hotel in the world at the time,{{sfn|Korom|2008|p=422}} covering the entire block. The slender central tower became known as the '''Waldorf Towers''', with its own private entrance on 50th Street, and consisted of 100 suites, about one third of which were leased as private residences.{{sfn|Morrison|2014|p=105}} President ] said on the radio, broadcast from the ]: "The opening of the new Waldorf Astoria is an event in the advancement of hotels, even in New York City. It carries great tradition in national hospitality...marks the measure of nation's growth in power, in comfort and in artistry...an exhibition of courage and confidence to the whole nation..."<ref name="history"/> ] managed the hotel in the 1930s and 1940s, a commanding figure who Tony Rey referred to as "the greatest hotelman of his era".{{sfn|Morehouse III|1991|p=40}} Boomer was elected chairman of the board of the Waldorf-Astoria Corporation on 20 February 1945, a position he held until his death in a plane crash in July 1947.{{sfn|Morehouse III|1991|p=46-7}} | ||

| From its inception, the Waldorf Astoria gained renown for its glamorous dinner parties and galas, often at the center of political conferences and fundraising schemes. One dinner, a relatively "small dinner" attended by some 50 people in June 1946, raised over $250,000.{{sfn|Schweber|2009|p=115}} From 27 to 29 March 1949, the ] held at the hotel to discuss the emerging ] and the growing divide between the US and the Soviet Union. The event was organized by the struggling ], but was sponsored by many individuals who were not Stalinists such as ], ], ] and ], with the intention of promoting peace.{{Sfn|Sorin|2002|p=109}} The conference was attended by the likes of Soviet Foreign Minister ], composer and pianist ] and writer ]. Tensions mounted during the controversial event, and culminated when Shostakovich, in front of a crowd of some 800 people, launched a scathing attack on western civilization, remarking that "a small clique of hatemongers was preparing world public opinion for the transition from cold war to outright aggression".{{Sfn|Carroll|2006|p=25}} The event was picketed in a counter-attack by anti-Stalinists running under the banner of "]" (AIF), and prominent individuals such as ], ], ], ] and ] publicly denounced Stalinism at the hotel.{{Sfn|Sorin|2002|p=109}} | From its inception, the Waldorf Astoria gained renown for its glamorous dinner parties and galas, often at the center of political conferences and fundraising schemes. One dinner, a relatively "small dinner" attended by some 50 people in June 1946, raised over $250,000.{{sfn|Schweber|2009|p=115}} The hotel played a considerable role in the emerging ] and international relations during the post-war years, staging numerous events and conferences. On March 15, 1946, ] attended a welcoming dinner at the hotel given by Governor ], ten days after making his famous ] speech.{{Sfn|Harbutt|1988|p=3}} From 27 to 29 March 1949, the ] held at the hotel to discuss the emerging ] and the growing divide between the US and the Soviet Union. The event was organized by the struggling ], but was sponsored by many individuals who were not Stalinists such as ], ], ] and ], with the intention of promoting peace.{{Sfn|Sorin|2002|p=109}} The conference was attended by the likes of Soviet Foreign Minister ], composer and pianist ] and writer ]. Tensions mounted during the controversial event, and culminated when Shostakovich, in front of a crowd of some 800 people, launched a scathing attack on western civilization, remarking that "a small clique of hatemongers was preparing world public opinion for the transition from cold war to outright aggression".{{Sfn|Carroll|2006|p=25}} The event was picketed in a counter-attack by anti-Stalinists running under the banner of "]" (AIF), and prominent individuals such as ], ], ], ] and ] publicly denounced Stalinism at the hotel.{{Sfn|Sorin|2002|p=109}} | ||

| Soon after the opening of the hotel in 1931, hotelier ], almost bankrupt at the time, reportedly cut out a photograph of the hotel from a magazine and wrote across it, "The Greatest of Them All".{{Sfn|Dana|2011|p=227}} He acquired management rights to the hotel on 12 October 1949.{{sfn|Taraborrelli|2014|p=118}}<ref>{{cite web | author=Stanley Turkel | title=A New Waldorf Against The Sky | url=http://www.oldandsold.com/articles08/waldorf-astoria-17.shtml | work=Old and Sold | year=1931 | accessdate=26 February 2011}}</ref> | Soon after the opening of the hotel in 1931, hotelier ], almost bankrupt at the time, reportedly cut out a photograph of the hotel from a magazine and wrote across it, "The Greatest of Them All".{{Sfn|Dana|2011|p=227}} He acquired management rights to the hotel on 12 October 1949.{{sfn|Taraborrelli|2014|p=118}}<ref>{{cite web | author=Stanley Turkel | title=A New Waldorf Against The Sky | url=http://www.oldandsold.com/articles08/waldorf-astoria-17.shtml | work=Old and Sold | year=1931 | accessdate=26 February 2011}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:49, 5 January 2015

For other uses, see Waldorf–Astoria (disambiguation).

| Waldorf Astoria New York | |

|---|---|

| File:WaldorfNewYork.svg | |

Waldorf Astoria, Park Avenue facade Waldorf Astoria, Park Avenue facade | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | 301 Park Avenue New York, New York 10022 United States |

| Opening | 1893 (Waldorf Hotel) 1897 (Astoria Hotel) 1931 (Waldorf-Astoria Hotel) |

| Owner | Anbang Insurance Group |

| Management | Waldorf Astoria Hotels and Resorts |

| Height | 190.5 m (625 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 47 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Schultze & Weaver Lee S Jablin, Harman Jablin Architects |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 1,413 |

| Number of restaurants | Peacock Alley Bull and Bear Steakhouse Oscar's Brasserie |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

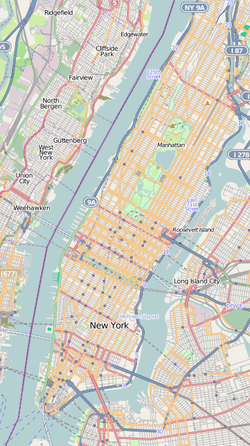

The Waldorf Astoria New York is a luxury hotel in New York City. It has been housed in two historic landmark buildings in New York. The first, a location on Fifth Avenue designed by architect Henry J. Hardenbergh, was closed in 1929 and razed for construction of the Empire State Building. The present building, at 301 Park Avenue in Manhattan, is a 47-story 190.5 m (625 ft) Art Deco landmark designed by architects Schultze and Weaver and dating from 1931.

Name

The name of the hotel is ultimately derived from Walldorf in Germany and the prominent German-American Astor family that originated there. The hotel was originally known as The Waldorf-Astoria with a single hyphen, as recalled by a popular expression and song, "Meet Me at the Hyphen." The sign was changed to a double hyphen, looking similar to an equals sign, by Conrad Hilton when he purchased the hotel in 1949. The double hyphen visually represents "Peacock Alley", the hallway between the two hotels that once stood where the Empire State building now stands today. The use of the double hyphen was discontinued by parent company Hilton in 2009, shortly after the introduction of the Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts chain. The hotel has since been known as the Waldorf Astoria New York, without any hyphen, though this is sometimes shortened to the Waldorf Astoria.

History

Original buildings

The original hotel started as two hotels on Fifth Avenue built by feuding relatives. The first hotel, the 13-story 450-room Waldorf Hotel, designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh in the German Renaissance style, was opened on 13 March 1893 at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, on the site where millionaire developer William Waldorf Astor had his mansion. The original hotel stood 225 feet (69 m) high, with a frontage of about 100 feet (30 m) on Fifth Avenue, with an area of 69,475 square feet (6,454.4 m). The original hotel was described as having a "lofty stone and brick exterior", which was "animated by an effusion of balconies, alcoves, arcades, and loggias beneath a tile rook bedecked with gables and turrets". An immediate success, it earned $4.5 million in its first year, exorbitant for that period. On 1 November 1897, Waldorf's cousin, John Jacob Astor IV, opened the 17-story Astoria Hotel on an adjacent site.

William Astor, motivated in part by a dispute with his aunt Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, had built the original Waldorf Hotel next door to her house, on the site of his father's mansion. The hotel was built to the specifications of founding proprietor George Boldt, who owned and operated the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, an elite boutique hotel on Broad Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with his wife Louise. Boldt was described as "Mild mannered, undignified, unassuming", resembling "a typical German professor with his close-cropped beard which he kept fastidiously trimmed... and his pince-nez glasses on a black silk chord". Boldt continued to own the Bellevue even after his relationship with the Astors blossomed. William Astor's construction of a hotel next to his aunt's house worsened his feud with her, but, with Boldt's assistance, John Astor persuaded his mother to move uptown. John Astor then built the Astoria Hotel and leased it to Boldt. The hotels were initially built as two separate structures, but Boldt planned the Astoria so it could be connected to the Waldorf by an alley. Peacock Alley was constructed to connect the two buildings, and the hotel subsequently became known as the "Waldorf-Astoria", the largest hotel in the world at the time.

With a telephone in every room and first-class room service, the hotel was designed specifically to cater to the needs of socially prominent "wealthy upper crust" of New York and distinguished foreign visitors to the city. The hotel became, according to author Sean Dennis Cashman, "a successful symbol of the opulence and achievement of the Astor family". It was the first hotel to offer complete electricity and private bathrooms. Founding proprietor Boldt, whose motto was "the guest is always right", became wealthy and prominent internationally, if not so much a popular celebrity as his famous employee, Oscar Tschirky, know as "Oscar of the Waldorf". The Waldorf Astoria was influential in advancing the status of women, who were admitted singly without escorts. George Boldt's wife, Louise Kehrer Boldt, was influential in evolving the idea of the grand urban hotel as a social center, particularly in making it appealing to women as a venue for social events. On 11 February 1899, Oscar hosted a lavish dinner reception which the New York Herald Tribune cited as the city's costliest dinner at the time. Some $250 was spent per guest, with bluepoint oysters, green turtle soup, lobster, ruddy duck and blue raspberries.

The United States Senate inquiry into the sinking of the RMS Titanic was opened at the hotel on 19 April 1912 and continued there for some time in the Myrtle Room, before moving on to Washington, D.C.. By the 1920s, the hotel was becoming dated, and the elegant social life of New York had moved much farther north than 34th Street. The Astor family sold the hotel to the developers of the Empire State Building and closed the hotel on 3 May 1929. It was demolished soon after.

-

The original Waldorf Hotel soon after opening in 1893

The original Waldorf Hotel soon after opening in 1893

-

Gentleman's Cafe at the Waldorf

Gentleman's Cafe at the Waldorf

-

After the addition of the much larger Astoria wing (1915)

After the addition of the much larger Astoria wing (1915)

-

Entrance to the Astoria

Entrance to the Astoria

Current building

The new building opened on Park Avenue, between East 49th and East 50th streets, 1 October 1931. It was the tallest and largest hotel in the world at the time, covering the entire block. The slender central tower became known as the Waldorf Towers, with its own private entrance on 50th Street, and consisted of 100 suites, about one third of which were leased as private residences. President Herbert Hoover said on the radio, broadcast from the White House: "The opening of the new Waldorf Astoria is an event in the advancement of hotels, even in New York City. It carries great tradition in national hospitality...marks the measure of nation's growth in power, in comfort and in artistry...an exhibition of courage and confidence to the whole nation..." Lucius Boomer managed the hotel in the 1930s and 1940s, a commanding figure who Tony Rey referred to as "the greatest hotelman of his era". Boomer was elected chairman of the board of the Waldorf-Astoria Corporation on 20 February 1945, a position he held until his death in a plane crash in July 1947.

From its inception, the Waldorf Astoria gained renown for its glamorous dinner parties and galas, often at the center of political conferences and fundraising schemes. One dinner, a relatively "small dinner" attended by some 50 people in June 1946, raised over $250,000. The hotel played a considerable role in the emerging Cold War and international relations during the post-war years, staging numerous events and conferences. On March 15, 1946, Winston Churchill attended a welcoming dinner at the hotel given by Governor Thomas E. Dewey, ten days after making his famous Iron Curtain speech. From 27 to 29 March 1949, the Waldorf World Peace Conference held at the hotel to discuss the emerging Cold War and the growing divide between the US and the Soviet Union. The event was organized by the struggling American Communist Party, but was sponsored by many individuals who were not Stalinists such as Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Albert Einstein and Aaron Copland, with the intention of promoting peace. The conference was attended by the likes of Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Y. Vishinisky, composer and pianist Dmitri Shostakovich and writer Alexsander Fadeyev. Tensions mounted during the controversial event, and culminated when Shostakovich, in front of a crowd of some 800 people, launched a scathing attack on western civilization, remarking that "a small clique of hatemongers was preparing world public opinion for the transition from cold war to outright aggression". The event was picketed in a counter-attack by anti-Stalinists running under the banner of "America for Intellectual Freedom" (AIF), and prominent individuals such as Irving Howe, Dwight Macdonald, Mary McCarthy, Robert Lowell and Norman Mailer publicly denounced Stalinism at the hotel.

Soon after the opening of the hotel in 1931, hotelier Conrad Hilton, almost bankrupt at the time, reportedly cut out a photograph of the hotel from a magazine and wrote across it, "The Greatest of Them All". He acquired management rights to the hotel on 12 October 1949. The Hilton Hotels Corporation finally bought the hotel outright in 1972. In 1975, George Lang was awarded the Hotelman of the Year Award. Then, Lee Jablin, of Harman Jablin Architects, fully renovated and upgraded the historical property to its original grandeur during the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s in a $150 million renovation. The hotel was named an official New York City Landmark in 1993. In 2006, Hilton launched Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts, a global luxury brand named for the iconic hotel. The Waldorf Astoria New York is a member of Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. "The Waldorf Towers" continues to operate as a boutique "hotel within a hotel".

In October 2014, it was announced that the Anbang Insurance Group, based in China, had purchased the Waldorf Astoria New York for US$1.95 billion, making it the most expensive hotel ever sold.

Architecture

The Art Deco hotel was designed by architects Schultze and Weaver and constructed at 301 Park Avenue, just north of Grand Central Terminal. That area was developed by building atop the existing railroad tracks leading to the station, with buildings like the Waldorf Astoria utilizing "air rights" to the space above the tracks. The new building opened on 1 October 1931. The 47-story 190.5 m (625 ft) hotel was the tallest and largest hotel in the world, and remained so for a number of years. 1,585 cubic feet (44.9 m) of black marble was imported from Belgium, 600 cubic feet (17 m) of Brech Montalto and 260 cubic feet (7.4 m) of Alps Green arrived from Italy, and some 300 antique mantles were brought in the furnish it. 200 railroad cars brought some 800,000 cubic feet (23,000 m) of limestone for the building's facing, 27,100 tons of steel for the skeleton superstructure, and 2,595,000 square feet (241,100 m) of terra cotta and gypsum block. The towers are brick-faced, which led many to believe that the builders ran out of money.

Peacock Alley, a 300 feet (91 m) long corridor lined with amber marble connects the two hotel buildings. Gilded, women of the times would enjoy walking along it and admiring themselves in the mirrors. The Peacock Alley restaurant of the Waldorf took its name from the alley. The hotel had its own railway platform, called Track 61, as part of Grand Central Terminal, used by Franklin D. Roosevelt, James Farley, Adlai Stevenson, and Douglas MacArthur, among others. An elevator large enough for Franklin D. Roosevelt's automobile provides access to the platform. However, it is rarely opened to the public.

Interior

Such is the architectural and cultural heritage of the hotel that tours are conducted of the hotel for guests. Frommer's has cited the hotel as an "icon of luxury", and highlights the "wide stately corridors, the vintage Deco door fixtures, the white-gloved bellmen, the luxe shopping arcade" and the "stunning round mosaic under an immense crystal chandelier" and the "free-standing Waldorf clock, covered with bronze relief figures" in the main lobby. They compare the decor of the rooms to those of an English country house, and describe the corridors as being wide and plush-carpeted which "seem to go on forever".

The lobby floor contains the room registration and cashier desks, the Empire Room and Hilton Room, the private Marco Polo Club, the Wedding Salon, Kenneth's Salon, the Peacock Alley lounge and restaurant, and Sir Harry's Bar. The elevator is furnished with paneled pollard oak and Carpathian elm. Special desks in the lobby are allocated to transportation and theatre, where exclusive tickets to many of the city's prominent theatres can be purchased. The lobby is furnished with polished nickel-bronze cornices and rockwood stone. The grand clock, a 4000 pound bronze was built by the Goldsmith's Company of London originally for the 1893 World Columbia Exposition in Chicago, but was purchased by the Waldorf owners. Its base is octagonal, with eight commemorative plaques of Presidents Washington, Lincoln, Grant, Jackson, Harrison and Cleveland, and Queen Victoria and Benjamin Franklin. Several boutiques surround the lobby, which contains Cole Porter's Steinway & Sons floral print decorated grand piano on the Cocktail Terrace, which the hotel had once given him as a gift.Porter was a resident at the hotel for 30 years and composed many of his songs here. The Empire Room is where many of the musical and dance performances were put on, from Count Basie, to Victor Borge, Gordon MacRae, George M. Cohan and Lena Horne, the first black performer at the hotel.

The third floor contains the Grand Ballroom, the Silver Corridor, the Basildon Room, the Jade Room and the Astor Gallery. Of note in the Astor Gallery are 12 allegorical females, painted by Edward Emerson Simmons. Every October the Paris Ball was held in the Grand Ballroom, before moving to the Americana (now the Sheraton Center). It hosted a memorable New Year's Eve party with Guy Lombardo and the Royal Canadians, and Lombardo used to broadcast live on the radio there from the "Starlight Roof". Maurice Chevalier performed at the ballroom in 1965 in his last appearance. The Silver Corridor outside the ballroom bears a resemblance to the Peacock Alley, but is shorter and wider. The fourth floor has the banquet and sales offices, and many of the suites including Barron, Vanderbilt, Windsor, Conrad, Vertes, Louis XVI and Cole Porter. The fourth floor was where the notorious Sunday night card games were played. In the main foyer is a chandelier measuring 10 feet (3.0 m) by 10 feet (3.0 m). There is also a re-creation of one of the living rooms of Hoover's Waldorf-Astoria suite in the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

Rooms and suites

The Waldorf Astoria and Towers has a total of 1416 hotel rooms as of 2009. The main hotel has 1235 single and double rooms and 208 mini suites, 17 of which are classified as "Astoria Level", which are upgraded rooms with deluxe amenities and complimentary access to the Astoria Lounge. The Waldorf Towers, from the 28th floor up to the 42nd, has 181 rooms, of which 115 are suites, with one to four bedrooms. The rooms retain the original Art Deco motifs, although each room is decorated differently. The guests rooms, classified as Deluxe, Superior, and Luxury, feature "Waldorf Serenity" beds and have a marble bath or shower with amenities designed by Salvatore Ferragamo. The suites featured King or Double beds and start in size at 450 square feet (42 m). The smallest are the One Bedroom suites, which range from 450 square feet (42 m) to 600 square feet (56 m), then there are the Signature suites, with a separate living room and one or two bedrooms, which range from 750 square feet (70 m) to 900 square feet (84 m), and finally the suites of The Towers which are generally larger and costlier still, and have a twice-daily maid service. The Tower suites are divided into standard ones, The Towers Luxury Series which have their own sitting room, the Towers Penthouse Series, the Towers Presidential-Style Suites, and finally the most expensive Presidential Suite on the 35th floor. The Penthouse Series contains three suites, The Penthouse, The Cole Porter Suite, and The Royal Suite, named after the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. They start at 1,800 square feet (170 m) in size, with two or more bedrooms, and are fitted with a kitchen and dining room which can accommodate for 8-12 guests. The Towers Presidential-Style Suites are divided into the MacArthur Suite and the Churchill Suite, and have their own grand entry foyer, and like the Penthouse Series, have their own kitchen and dining room. The 2,250 square feet (209 m) Presidential Suite is designed with Georgian-style furniture to emulate that of the White House. It has three large bedrooms and three bathrooms, and boasts numerous treasures, including the desk of General MacArthur and rocking chair of John F. Kennedy.

Other facilities

A 2,500 square feet (230 m) fitness center is on the 5th floor. The $21.5 million Waldorf Astoria Guerlain Spa was inaugurated on 1 September 2008 on the 19th floor. It features 16 treatment rooms and two relaxation lounges. The hotel has its own Business Center, a 1,150 square feet (107 m) digital facility, where guests can access the Internet and photocopy.

Restaurants and cuisine

The Waldorf Astoria was the first hotel to offer room service. An extensive menu is available for guests, with special menus for children and for dieters. The executive chef of the Waldorf for many years was John Doherty.

The hotel has three main restaurants, Peacock Alley, The Bull and Bear Steak House, and Oscar's Brasserie, as well as a secondary restaurant, the Japanese Inagiku. Peacock Alley, situated in the heart of the lobby, features an Art Deco design with gilded ceilings and includes a main restaurant, a bar and lounge, and three private dining salons. It is known primarily for its fish and seafood dishes. Sunday Brunch is particularly popular with locals and features over 180 gourmet dishes divided into 12 themed displays, with cuisine ranging from lobster and oysters to Belgian waffles, Eggs Benedict, omelettes, and hollandaise sauces. The Bull and Bear Steak House is furnished in richly polished wood, and has a "den-like" atmosphere, and is reportedly the only restaurant on the East Coast which serves 28 days prime grade USDA Certified Angus Beef. Between 2007 and 2010, the restaurant was the filming location for Fox Business Happy Hour, presented live between 5 and 6 pm. The Bull and Bear Bar is based on the original Waldorf Astoria Bar, which was a favorite haunt of many of the financial elite of the city from the hotel's inception in 1893, such as Diamond Jim Brady, Buffalo Bill Cody and Bat Masterson. Behind the bar are bronze statues of a bull and a bear, which represent the successful men of Wall Street. The Inagiku serves contemporary Japanese cuisine. The restaurant opens for lunch on weekdays and cocktails and dinner in the evenings. Guests have the option to reserve private orthodox tatami rooms.

Oscar's Brasserie, overlooking Lexington Avenue in what was once a Savarin restaurant, is designed by Adam Tihany. The restaurant takes its name from Oscar Tschirky (Oscar of the Waldorf), maître d'hôtel from the hotel's inauguration in 1893 until his retirement in 1943, who authored The Cookbook by Oscar of The Waldorf (1896). The restaurant serves traditional American cuisine, with many dishes based upon the cookbook which have gained world renown, including the Waldorf salad, Eggs Benedict, Thousand Island dressing, and Veal Oscar. The Waldorf salad—a salad made with apples, walnuts, celery, grapes, and mayonnaise or a mayonnaise-based dressing—was first created in 1896 at the Waldorf by Oscar. The original recipe, however did not contain nuts, but they had been added by the time the recipe appeared in The Rector Cook Book in 1928. The salad is mentioned in the 1934 Cole Porter song "You're the Top", and was also popularized by its central role in the plot of the "Waldorf Salad" episode of the 1970s British sitcom Fawlty Towers. Tschirky was also noted for his "Oscar's Sauce", which became so popular that it was sold at the hotel.

Sir Harry's Bar is one of the principal bars of the hotel, situated just off the main lobby. It is named after British Sir Harry Johnston (1858 – 1927). In the 1970s the bar was renovated in a "plush African safari" design to honor Johnston, a notable explorer of Africa, with "zebra-striped wall coverings and carpeting, with bent-cane furnishings". It has since been redecorated back to a more conservative design, with walnut paneling and leather banquettes. A number of cocktails were invented at the bar, including the Rob Roy (1894) and the Bobbie Burns. Frank Sinatra frequented Sir Harry's Bar for many years. In 1991, while drinking at the bar with Jilly Rizzo and Steve Lawrence, he was approached by a fan asking for an autograph. Sinatra responded, "Don't you see I'm on my own time here? You asshole. What's wrong with you?". The fan said something which angered Sinatra, who lunged at the fan, and Sinatra had to be restrained.

Notable residents and tenants

Leaders and businesspeople

From its inception, the Waldorf was always a "must stay" hotel for foreign dignitaries. The viceroy of China, Li Hung Chang stayed at the hotel in 1896 and feasted on hundred-year-old eggs which he brought with him. Over the years many royals from around the world stayed at the Waldorf Astoria including Shahanshah of Iran and Empress Farah, King Frederick IX and Queen Ingrid of Denmark, Princess Astrid of Norway, Crown Prince Olav and Crown Princess Martha of Norway, King Baudouin I of Belgium and Queen Fabiola, Prince Albert and Princess Paola of Belgium, King Hussein I of Jordan, Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, King Michael of Romania, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of England, Mohammed Zahir Shah and Homaira Shah of Afghanistan, King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Queen Sirikit of Thailand, and Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko of Japan and many others. Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip stayed at the hotel during their first visit to America on 21 October 1957, and a banquet was held for them in the Grand Ballroom. In the Bicentennial year in 1976, most of the heads of state from around the world and all of the Kings and Queens of Europe were invited to the hotel.

In modern times, the clientele of the Waldorf is more typically wealthy politicians and businessmen than playboys and royalty. An entire floor was often rented out to wealthy Saudi Arabians with their own staff, and it was kept out of bounds to others due to the fact that they reportedly often walked around naked and had some bizarre eating habits and practices such as roasting monkeys and snakes. Wealthy Japanese businessman during their stay would sometimes remove the furniture and replace it with their own floors mats. One early wealthy resident was Chicago businessman J. W. Gates who would gamble on stocks on Wall Street and play poker at the hotel. He paid up to $50,000 a year to hire suites at the hotel. Grand Duchess Victoria Federova was invited by Waldorf president Lucius Bloomer to stay at the hotel in the 1920s. Demands by people of prominence could often be exorbitant or bizarre, and Fidel Castro once walked into the hotel with a flock of live chickens, insisting that they be killed and freshly cooked on the premises to his satisfaction, only to be turned away. While serving as Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger ordered all of the antiques to be removed from one suite and replaced them with 36 desks for his staff. An unnamed First Lady also once demanded that all of the bulbs in her suite be changed to 100 watt ones and kept on all day and night to simulate daylight; she further insisted that there be an abundance of chewing gum available.

Postmaster General James Farley occupied two adjoining suites in the current Waldorf Astoria during his tenure as the Chairman of the Board of Coca-Cola's International division from 1940 until his death in 1976, arguably one of the landmark's longest housed tenants. The Presidential Suite at the hotel come from when, during the 1950s and early 1960s, former U.S. president Herbert Hoover and retired U.S. General Douglas MacArthur lived in suites on different floors of the hotel. Hoover lived there for over 30 years from after the end of his presidency until he died in 1964;. former President Dwight D. Eisenhower lived there until he died in 1969. MacArthur's widow, Jean MacArthur, lived there from 1952 until her death in 2000. A plaque affixed to the wall on the 50th Street side commemorates this. Since then, every President of the United States since Hoover has either stayed over or lived in the Waldorf Astoria, although Jimmy Carter claimed to have never stayed overnight at the hotel. Nancy Reagan was reputedly not fond of the suite.

The official residence of the United States' Permanent Representative to the United Nations is located in the Waldorf Towers. Carlos P. Romulo, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines and member of the UN had suite 3600, below Hoover's, for some 45 years from 1935 onwards, and fellow Filipino Imelda Marcos also spent much time and money at the hotel. Another connection with the Philippines is that many meetings were held here between President Manuel L. Quezon and high ranking American politicians and senators. Through the meetings, Quezon encouraged investment into the country and convinced General MacArthur to accompany him back to the Philippines as his military adviser.

Celebrities

During the 1930s, gangster Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel owned an apartment at the Waldorf. Around the time of World War I, inventor Nikola Tesla lived in the earlier Waldorf-Astoria.

Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra

Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra

Due to the number of high profile guests staying at the hotel at any one time, author Ward Morehouse III has referred to the Towers as a "kind of vertical Beverly Hills. On any one given night you might find Dinah Shore, Gregory Peck, Frank Sinatra Zsa Zsa Gabor staying there". Gabor married Conrad Hilton in 1941. In 1955, Marilyn Monroe stayed at the hotel for several months, but due to costs of trying to finance her production company "Marilyn Monroe Productions", only being paid $1,500 a week for her role in The Seven Year Itch and being suspended from 20th Century Fox for walking out on Fox after creative differences, living at the hotel became too costly and Monroe had to move into a different hotel in New York City. Around the same time, Cole Porter and Linda Lee Thomas had an apartment in the Waldorf Towers, where Thomas died in 1954. Porter's 1934 song "You're the Top", contains the lyric, "You're the top, you're a Waldorf salad..." The Cole Porter Suite, Suite 33A, was the place where Porter lived and entertained for a period; Frank Sinatra paid nearly $1 million a year to keep a personal suite at the hotel between 1979 and 1988, which he called "home" when out of Los Angeles. Sinatra took over part of the hotel during the filming of The First Deadly Sin in 1980. Grace Kelly and Rainier III were regulars guests at the hotel. At one time Kelly was reputed to be in love with the hotel banquet manager of the Waldorf, Claudius Charles Philippe. Elizabeth Taylor frequented the hotel, and would often attend galas at the hotel to talk about her various causes. Her visits were excitedly awaited by the hotel staff, who would prepare long in advance. Taylor was honored at the 1983 Friars Club dinner at the hotel. Ava Gardner, Liv Ullmann, Edward G. Robinson, Gregory Peck and Ray Bolger also stayed at the hotel.

During her childhood in the 1980s and 1990s, Paris Hilton lived with her family in the hotel. From 1992 to 2013, Kenneth, sometimes called the world's first celebrity hairdresser, famed for creating Jacqueline Kennedy's bouffant in 1961, was responsible for the hairdressing and beauty salon.

In film and television

The Waldorf Astoria has been a filming location for numerous films and TV series. Ginger Rogers headlined an all star ensemble cast in the 1945 film Week-End at the Waldorf, set at the hotel and filmed partially on location there. Other films shot at the hotel include Broadway Danny Rose (1984), Coming To America, Scent of a Woman (1992), The Cowboy Way (1994), Random Hearts (1999), Analyze This (1999), For Love of the Game (1999), Serendipity (2000), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Maid in Manhattan (2002), Two Weeks Notice (2002), End of the Century (2005), Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), The Pink Panther (2006), and The Hoax (2007). Television series which have filmed at the Waldorf include Law and Order, Rescue Me, Sex and the City, The Sopranos and Will and Grace.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (7 October 2014). "Waldorf-Astoria to Be Sold in a $1.95 Billion Deal". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Waldorf Astoria New York at Emporis

- "Waldorf Astoria New York". SkyscraperPage.

- Waldorf Astoria New York at Structurae

- Emmerich 2013, p. 7.

- "The Waldorf-Astoria". Edwardianpromenade.com. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "Waldorf Astoria Drops the Equals Sign We'd Barely Noticed". HotelChatter. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Hirsh 1997, p. 61.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 20.

- ^ "Hotel history". Waldorfnewyork.com. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 132.

- Morrison 2014, p. 11. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMorrison2014 (help)

- ^ Seifer 1998, p. 204.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 21.

- ^ "Guard shot during robbery attempt at Waldorf-Astoria". CNN. 17 October 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2015. Cite error: The named reference "cnn" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- "The Waldorf Astoria". New York Architecture. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Bernardo 2010, p. 40.

- Morrison III 2014, p. 8. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMorrison_III2014 (help)

- Cashman 1988, p. 373.

- ^ "Hotel fact sheet" (PDF). New York University School of Professional Studies. 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 18.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 32.

- Kuntz 1998, p. 77. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKuntz1998 (help)

- "Six Degrees of Titanic". History.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Korom 2008, p. 422.

- Morrison 2014, p. 105. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMorrison2014 (help)

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 40.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 46-7.

- Schweber 2009, p. 115.

- Harbutt 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Sorin 2002, p. 109.

- Carroll 2006, p. 25.

- Dana 2011, p. 227.

- Taraborrelli 2014, p. 118.

- Stanley Turkel (1931). "A New Waldorf Against The Sky". Old and Sold. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "New York Luxury Hotels & 5 Star Vacations - The Waldorf Astoria New York Legacy". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 119.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 57.

- Frank, Robert (6 October 2014). "Waldorf becomes most expensive hotel ever sold: $1.95 billion". CNBC. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- "Chapter 6: Historic Resources" (PDF). East Side Access Project, mta.info. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 53.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 130.

- "Waldorf-Astoria's private rail platform forever closed". NewYorkology. 7 February 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- Nelson, Craig (11 November 2013). "Secrets of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel". New York.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Brennan, Joe (2002). "Grand Central Terminal, Waldorf-Astoria platform". Abandoned Stations. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Flippin 2011, p. 34.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 141.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 54.

- ^ Davis 2011, p. 27.

- Martinez, Jose (20 July 2010). "Cole Porter's apartment at the Waldorf-Astoria can be yours for $140K a month". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Morehouse III 1991, pp. 60–1.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 55.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 140.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 64–5.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 142.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 96.

- ^ Mayerowitz, Scott (22 September 2009). "Behind the Scenes at the Waldorf Astoria's Posh Presidential Suite". ABC News. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- "Waldorf New York Guest Rooms". Waldorfnewyork.com. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- "Suite Amenities". Waldorfnewyork.com. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "Rooms and suites". Waldorfnewyork.com. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 151.

- Hilton 1957, p. 227.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 8.

- "Dining". Waldorfnewyork.com. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 121. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMorrison2014 (help)

- "The History of Waldorf Salad". Kitchen Project. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- Leah A. Zeldes (7 October 2009). "Eat this! Waldorf Salad, A Apple-licious Fall Favorite". Dining Chicago. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 24.

- Rojek 2011, p. 141. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRojek2011 (help)

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 106.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 117.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 147.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 139.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 22.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 27.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 168.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 161.

- Scroop, Daniel (2006). Mr. Democrat: Jim Farley, the New Deal, and the Making of Modern American Politics (PDF). press.umich.edu. pp. 215–229. ISBN 9780472021505. OCLC 646794810. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Christopher Klein (7 October 2014). "Iconic Waldorf Astoria Hotel Changes Hands". History. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 148.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 14.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 151–4.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 154.

- "Biography of a Gangster". Essortment.com. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- Broad, William J. (4 May 2009). "A Battle to Preserve a Visionary's Bold Failure". New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Morehouse III 1991, p. 137.

- "Marilyn Monroe's Personal Waldorf-Astoria Hotel Invoices". Marilynmonroecollection.com. 18 December 1956. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 6, 146.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 133.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 136.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 9.

- Morehouse III 1991, p. 143.

- Morehouse III 1991, pp. 10–2.

- Reed 2012, p. 25.

- Wong 2010, p. 151.

- Collins, Amy Fine (1 June 2003). "It had to be Kenneth.(hairstylist Kenneth Battelle)(Interview)". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

Bibliography

- Bernardo, Mark (1 July 2010). Mad Men's Manhattan: The Insider's Guide. Roaring Forties Press. ISBN 978-0-9843165-7-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carroll, Mark (2 November 2006). Music and Ideology in Cold War Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03113-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cashman, Sean Dennis (1988). America in the Age of the Titans: The Progressive Era and World War I. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1411-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dana, Leo Paul (1 January 2011). World Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84980-845-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Gerry Hempel (16 November 2011). Romancing the Roads: A Driving Diva's Firsthand Guide, East of the Mississippi. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58979-620-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Emmerich, Alexander (24 July 2013). John Jacob Astor and the First Great American Fortune. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0382-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flippin, Alexis Lipsitz (25 January 2011). Frommer's New York City with Kids. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-01949-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harbutt, Fraser J. (1988). The Iron Curtain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536377-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hilton, Conrad Nicholson (1957). Be My Guest. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-76174-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hirsh, Jeff (1997). Manhatten Hotels 1880-1920. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5749-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Korom, Joseph J. (2008). The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of Height. Branden Books. ISBN 978-0-8283-2188-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuntz, Tom; Smith, William Alden (1 March 1998). The Titanic Disaster Hearings. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-02553-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morehouse III, Ward (1991). The Waldorf Astoria: America's Gilded Dream. Xlibris, Corp. ISBN 978-1413465044.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morrison, William Alan (14 April 2014). Waldorf Astoria. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2128-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pommer, Alfred; Pommer, Joyce (2013). Exploring Manhattan's Murray Hill. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62619-059-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reed, Paula (2012). Fifty Fashion Looks that Changed the 1960s. Design Museum, London: Hachette UK. ISBN 1840916176.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rojek, Chris (2004). Frank Sinatra. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-3090-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schweber, Silvan S. (30 June 2009). Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04335-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Seifer, Marc (1 May 1998). Wizard: The Life And Times Of Nikola Tesla: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla. Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-3556-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sorin, Gerald (2002). Irving Howe: A Life of Passionate Dissent. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9821-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taraborrelli, J. Randy (1 April 2014). The Hiltons: The True Story of an American Dynasty. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4555-8236-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (11 May 2010). AIA Guide to New York City. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977291-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wong, Aliza Z. (2010). Julie Willett (ed.). The American beauty industry encyclopedia: Hairstylists, Celebrity. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood. ISBN 9780313359491.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Crockett, Albert Stevens (1 August 2005). The Old Waldorf-Astoria Bar Book. New Day Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9743259-0-3.

- Morrison, William Alan (14 April 2014). Waldorf Astoria. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2128-6.

External links

- Official website

- Waldorf Astoria at the Internet Archive

- The Astor Collection at the University of Virginia virtual exhibition of Native American artifacts originally displayed in the Grill Room of the Astor Hotel

- "The Waldorf Astoria - Host To The World", DVD-2008

- Waldorf-Astoria at History of New York City

- The Waldorf Astoria Archive

| Venues of the Tony Awards ceremonies | |

|---|---|

|

| Timeline of the world's tallest hotels | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hilton Worldwide | |

|---|---|

| Luxury | |

| Lifestyle | |

| Full service | |

| Focused service | |

| All suites | |

| Vacation ownership | |

| Loyalty program | |

| Former divisions | |

- 1893 establishments in New York

- Art Deco architecture in New York City

- Astor family

- Destroyed landmarks in New York City

- Full-block structures in New York City

- Hilton Hotels & Resorts hotels

- Hotel buildings completed in 1931

- Hotels established in 1893

- Hotels in Manhattan

- Midtown Manhattan

- Park Avenue

- Presidential homes in the United States

- Railway hotels in the United States

- Skyscraper hotels in New York City

- Skyscrapers between 150 and 199 meters

- Skyscrapers in Manhattan

- Fifth Avenue (Manhattan)