| Revision as of 18:16, 12 October 2014 editSamEV (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers16,886 edits →Shasu of Yhw: word choice← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:24, 13 January 2015 edit undo174.4.163.53 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

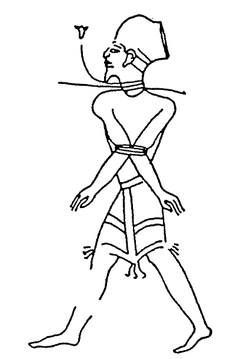

| ] wall carving.]] | ] wall carving.]] | ||

| There are two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of Amenophis III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of Ramses II (13th century BCE) which refer to 'Yahu in the land of the Šosū-Bedouins',(''t<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup> š<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup>św jhw<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup>''), in which ''Yahu'' is a ]. Regarding the Shasu of Yhw, Michael Astour observed that the "hieroglyphic rendering corresponds very precisely to the Hebrew tetragrammaton ], or ], and antedates the hitherto oldest occurrence of that Divine Name – on the ] – by over five hundred years."<ref>Astour (1979), p. 18</ref> One hypothesis is that it is reasonable to infer that the ] 'Israel' recorded on the ] refers to a Shasu enclave, and that, since later Biblical tradition portrays |

There are two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of Amenophis III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of Ramses II (13th century BCE) which refer to 'Yahu in the land of the Šosū-Bedouins',(''t<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup> š<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup>św jhw<sup><span style="font-size:80%">3</span></sup>''), in which ''Yahu'' is a ]. Regarding the Shasu of Yhw, Michael Astour observed that the "hieroglyphic rendering corresponds very precisely to the Hebrew tetragrammaton ], and antedates the hitherto oldest occurrence of that Divine Name – on the ] – by over five hundred years."<ref>Astour (1979), p. 18</ref> One hypothesis is that it is reasonable to infer that the ] 'Israel' recorded on the ] refers to a Shasu enclave, and that, since later Biblical tradition portrays YHWH "coming forth from ]"<ref>], 5:4),</ref> the Shasu, originally from ] and northern ], went on to form one major element in the amalgam that was to constitute the "Israel" which later established the ].<ref>] (1992), p. 272–3,275.</ref> Rainey has a similar view in his analysis of the ].<ref>Rainey (2008)</ref> K. Van Der Toorn concludes that, | ||

| <blockquote>By the 14th century BC, before the |

<blockquote>By the 14th century BC, before the cult of Yahweh had reached Israel, groups of Edomite and Midianites worshipped Yahweh as their god.<ref>K. Van Der Toorn,''Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life,'' BRILL 1996 p.282-283.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| Objections exist that state that the proposed link between |

Objections exist that state that the proposed link between the ] of YHWH and the Shasu of Yhw is uncertain, given that in the Merneptah reliefs, the group later known as the Israelites are not described or depicted as Shasu. The Shasu are usually depicted hieroglyphically with a ] indicating a land not a people.<ref>Dermot Anthony Nestor, ''Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity,'' Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010 p.185.</ref> Frank J. Yurco and Michael G. Hasel would distinguish the Shasu in Merneptah's Karnak reliefs from the people of Israel since they wear different clothing, hairstyles, and are determined differently by Egyptian scribes.<ref>Yurco (1986), p. 195, 207; Hasel (2003), p. 27–36.</ref> Moreover, Israel is determined as a people, though not necessarily as a socioethnic group.<ref>Kenton L. Sparks, ''Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and Their Expression in the Hebrew Bible,''Eisenbrauns, 1998, p.108: 'If the Egyuptian scribe was not clear on the nature of the entity he called "Israel," knowing only that it was "different" from the surrounding modalities, then we can imagine something other than a sociocultural Israel. It is possible that Israel represented a confederation of united, but sociologically distinct, modalities that were joined either culturally or politically via treaties and the like. This interpretation of the evidence would allow for the unity implied by the endonymic evidence and also give our scribe some latitude in his use of the determinative'.</ref> Egyptian scribes tended to bundle up rather disparate groups of people under one 'artificial unifying rubric.'<ref>Nestor, ''Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity,''p.186.</ref> The most frequent designation for the "foes of Shasu" is the ].<ref>Hasel (2003), p. 32–33</ref> Thus they are differentiated from the ], who are defending the fortified cities of Ashkelon, ], and Yenoam.<ref>Stager (2001), p. 92</ref> At the same time, the hill-country determinative is not always used for Shasu, as is the case in the "Shasu of Yhw" name rings from Soleb and Amarah-West. Gösta Werner Ahlström argued that the reason Shasu and Israelites are differentiated from each other in the Merneptah Stele is that these Shasu were nomads while the Israelites were a sedentary subset of the Shasu.<ref name="Ahlström1993">{{cite book|author=Gösta Werner Ahlström|title=The History of Ancient Palestine|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5cSAlLBZKaAC&pg=PA277|year=1993|publisher=Fortress Press|isbn=978-0-8006-2770-6|pages=277–278}}</ref> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 07:24, 13 January 2015

Shasu (from Egyptian Šsw, probably pronounced Shasw) were Semitic-speaking cattle nomads in the Levant from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age or Third Intermediate Period of Egypt. They were organized in clans under a tribal chieftain, and were described as brigands active from the Jezreel Valley to Ashkelon and the Sinai.

The name evolved from a transliteration of the Egyptian word šsw, meaning "those who move on foot", into the term for Bedouin-type wanderers. The term originated in a 15th-century BCE list of peoples in Transjordan. It is used in a list of enemies inscribed on column bases at the temple of Soleb built by Amenhotep III. Copied later by either Seti I or Ramesses II at Amarah-West, the list mentions six groups of Shasu: the Shasu of S'rr, the Shasu of Rbn, the Shasu of Sm't, the Shasu of Wrbr, the Shasu of Yhw, and the Shasu of Pysps.

Shasu of Yhw

There are two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of Amenophis III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of Ramses II (13th century BCE) which refer to 'Yahu in the land of the Šosū-Bedouins',(t šśw jhw), in which Yahu is a toponym. Regarding the Shasu of Yhw, Michael Astour observed that the "hieroglyphic rendering corresponds very precisely to the Hebrew tetragrammaton YHWH, and antedates the hitherto oldest occurrence of that Divine Name – on the Moabite Stone – by over five hundred years." One hypothesis is that it is reasonable to infer that the demonym 'Israel' recorded on the Merneptah Stele refers to a Shasu enclave, and that, since later Biblical tradition portrays YHWH "coming forth from Se'ir" the Shasu, originally from Moab and northern Edom, went on to form one major element in the amalgam that was to constitute the "Israel" which later established the Kingdom of Israel. Rainey has a similar view in his analysis of the el-Amarna letters. K. Van Der Toorn concludes that,

By the 14th century BC, before the cult of Yahweh had reached Israel, groups of Edomite and Midianites worshipped Yahweh as their god.

Objections exist that state that the proposed link between the Israelites of YHWH and the Shasu of Yhw is uncertain, given that in the Merneptah reliefs, the group later known as the Israelites are not described or depicted as Shasu. The Shasu are usually depicted hieroglyphically with a determinative indicating a land not a people. Frank J. Yurco and Michael G. Hasel would distinguish the Shasu in Merneptah's Karnak reliefs from the people of Israel since they wear different clothing, hairstyles, and are determined differently by Egyptian scribes. Moreover, Israel is determined as a people, though not necessarily as a socioethnic group. Egyptian scribes tended to bundle up rather disparate groups of people under one 'artificial unifying rubric.' The most frequent designation for the "foes of Shasu" is the hill-country determinative. Thus they are differentiated from the Canaanites, who are defending the fortified cities of Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yenoam. At the same time, the hill-country determinative is not always used for Shasu, as is the case in the "Shasu of Yhw" name rings from Soleb and Amarah-West. Gösta Werner Ahlström argued that the reason Shasu and Israelites are differentiated from each other in the Merneptah Stele is that these Shasu were nomads while the Israelites were a sedentary subset of the Shasu.

See also

Notes

- Donald B. Redford (1992), p. 271.

- Robert D. Miller (II.),Chieftains Of The Highland Clans: A History Of Israel In The Twelfth And Eleventh Centuries B.C., Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005, p.95

- Sivertsen (2009), p. 118

- Hasel (1998), p. 219

- Astour (1979), p. 18

- Book of Judges, 5:4),

- Donald B. Redford (1992), p. 272–3,275.

- Rainey (2008)

- K. Van Der Toorn,Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life, BRILL 1996 p.282-283.

- Dermot Anthony Nestor, Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010 p.185.

- Yurco (1986), p. 195, 207; Hasel (2003), p. 27–36.

- Kenton L. Sparks, Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic Sentiments and Their Expression in the Hebrew Bible,Eisenbrauns, 1998, p.108: 'If the Egyuptian scribe was not clear on the nature of the entity he called "Israel," knowing only that it was "different" from the surrounding modalities, then we can imagine something other than a sociocultural Israel. It is possible that Israel represented a confederation of united, but sociologically distinct, modalities that were joined either culturally or politically via treaties and the like. This interpretation of the evidence would allow for the unity implied by the endonymic evidence and also give our scribe some latitude in his use of the determinative'.

- Nestor, Cognitive Perspectives on Israelite Identity,p.186.

- Hasel (2003), p. 32–33

- Stager (2001), p. 92

- Gösta Werner Ahlström (1993). The History of Ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. pp. 277–278. ISBN 978-0-8006-2770-6.

References

- Dever, William G. (1997). "Archaeology and the Emergence of Early Israel" . In John R. Bartlett (Ed.), Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation, pp. 20–50. Routledge.

- Hasel, Michael G. (1994). "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 296, pp. 45–61.

- Hasel, Michael G. (1998). Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 BC. Probleme der Ägyptologie 11. Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–239. ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Hasel, Michael G. (2003). "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in Beth Alpert Nakhai ed. The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 19–44. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 0-89757-065-0

- Hoffmeier, James K. (2005). Ancient Israel in Sinai, New York: Oxford University Press, 240–45.

- Horn, Siegfried H. (1953). "Jericho in a Topographical List of Ramesses II," Journal of Near Eastern Studies 12: 201–203.

- Sivertsen, Barbara J. The Parting of the Sea Princeton University Press. Princeton University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-691-13770-4

- Rainey, Anson (2008). "Shasu or Habiru. Who Were the Early Israelites?" Biblical Archeology Review 34:6 (Nov/Dec).

- Astour, Michael C. (1979). "Yahweh in Egyptian Topographic Lists." In Festschrift Elmar Edel, eds. M. Gorg & E. Pusch, Bamberg.

- MacDonald, Burton (1994). "Early Edom: The Relation between the Literary and Archaeological Evidence". In Michael D. Coogan, J. Cheryl Exum, Lawrence E. Stager (Eds.), Scripture and Other Artifacts: Essays on the Bible and Archaeology in Honor of Philip J. King, pp. 230–246. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22364-8

- Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan and Israel In Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00086-7.

- Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel". In Michael Coogan (Ed.), The Oxford History of the Biblical World, pp. 90–129. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508707-0

- Yurco, Frank J. (1986). "Merenptah's Canaanite Campaign." Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 23:189–215.