| Revision as of 00:36, 10 January 2015 edit192.12.146.229 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:02, 13 January 2015 edit undo199.216.110.27 (talk) classes of hiTag: Possible vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

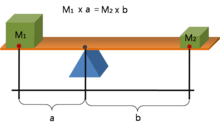

| This relationship shows that the mechanical advantage can be computed from ratio of the distances from the fulcrum to where the input and output forces are applied to the lever, assuming no losses due to friction, flexibility or wear. | This relationship shows that the mechanical advantage can be computed from ratio of the distances from the fulcrum to where the input and output forces are applied to the lever, assuming no losses due to friction, flexibility or wear. | ||

| ==Classes of levers== | |||

| lever | |||

| ] | |||

| Levers are classified by the relative positions of the fulcrum and the input and output forces. It is common to call the input force ''the effort'' and the output force ''the load'' or ''the resistance.'' This allows the identification of three classes of levers by the relative locations of the fulcrum, the resistance and the effort:<ref >{{cite book | |||

| |title=Physics in Biology and Medicine, Third edition | |||

| |first1=Paul |last1=Davidovits | |||

| |publisher=Academic Press | |||

| |year=2008 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-12-369411-9 | |||

| |page=10 | |||

| |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=e9hbt3xisb0C&pg=PA10 | |||

| |chapter=Chapter 1 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| *'''{{visible anchor|Class 1}}''': Fulcrum in the middle: the effort is applied on one side of the fulcrum and the resistance on the other side, for example, a ] or a ]. Mechanical advantage may be greater or less than 1. | |||

| *'''{{visible anchor|Class 2}}''': Resistance in the middle: the effort is applied on one side of the resistance and the fulcrum is located on the other side, for example, a ], a ], a ] or the ] ] of a car. Mechanical advantage is always greater than 1. | |||

| *'''{{visible anchor|Class 3}}''': Effort in the middle: the resistance is on one side of the effort and the fulcrum is located on the other side, for example, a pair of ] or the ]. Mechanical advantage is always less than 1. | |||

| These cases are described by the mnemonic "fre 123" where the fulcrum is in the middle for the 1st class lever, the resistance is in the middle for the 2nd class lever, and the effort is in the middle for the 3rd class lever. Another way to remember this is the mnemonic for what is in the middle. First order, Fulcrum in the middle; second order, Load (Resistance) in the middle; third order, Effort in the middle. The mnemonic is Levers Flex. | |||

| ==Law of the lever== | ==Law of the lever== | ||

Revision as of 22:02, 13 January 2015

This article is about the simple machine. For other uses, see Lever (disambiguation).| Lever, one of the six simple machines | |

|---|---|

Levers can be used to exert a large force over a small distance at one end by exerting only a small force over a greater distance at the other. Levers can be used to exert a large force over a small distance at one end by exerting only a small force over a greater distance at the other. | |

| Classification | Simple machine |

| Industry | Construction |

| Weight | Mass times gravitational acceleration |

| Fuel source | potential and kinetic energy {mechanical energy } |

| Components | fulcrum or pivot, load and effort |

A lever (/ˈlɛvər/ or UK: /ˈliːvər/) is a machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or fulcrum. It is one of the six simple machines identified by Renaissance scientists. The word comes from the French lever, "to raise", cf. a levant. A lever amplifies an input force to provide a greater output force, which is said to provide leverage. The ratio of the output force to the input force is the mechanical advantage of the lever.

Early use

The earliest remaining writings regarding levers date from the 3rd century BC and were provided by Archimedes. "Give me a place to stand, and I shall move the Earth with it" is a remark of Archimedes who formally stated the correct mathematical principle of levers (quoted by Pappus of Alexandria).

It is assumed that in ancient Egypt, constructors used the lever to move and uplift obelisks weighing more than 100 tons.

Force and levers

A lever is a beam connected to ground by a hinge, or pivot, called a fulcrum. The ideal lever does not dissipate or store energy, which means there is no friction in the hinge or bending in the beam. In this case, the power into the lever equals the power out, and the ratio of output to input force is given by the ratio of the distances from the fulcrum to the points of application of these forces. This is known as the law of the lever.

The mechanical advantage of a lever can be determined by considering the balance of moments or torque, T, about the fulcrum,

where M1 is the input force to the lever and M2 is the output force. The distances a and b are the perpendicular distances between the forces and the fulcrum.

The mechanical advantage of the lever is the ratio of output force to input force,

This relationship shows that the mechanical advantage can be computed from ratio of the distances from the fulcrum to where the input and output forces are applied to the lever, assuming no losses due to friction, flexibility or wear.

lever

Law of the lever

The lever is a movable bar that pivots on a fulcrum attached to a fixed point. The lever operates by applying forces at different distances from the fulcrum, or a pivot.

Assuming the lever does not dissipate or store energy, the power into the lever must equal the power out of the lever. As the lever rotates around the fulcrum, points farther from this pivot move faster than points closer to the pivot. Therefore a force applied to a point farther from the pivot must be less than the force located at a point closer in, because power is the product of force and velocity.

If a and b are distances from the fulcrum to points A and B and let the force FA applied to A is the input and the force FB applied at B is the output, the ratio of the velocities of points A and B is given by a/b, so we have the ratio of the output force to the input force, or mechanical advantage, is given by

This is the law of the lever, which was proven by Archimedes using geometric reasoning. It shows that if the distance a from the fulcrum to where the input force is applied (point A) is greater than the distance b from fulcrum to where the output force is applied (point B), then the lever amplifies the input force. On the other hand, if the distance a from the fulcrum to the input force is less than the distance b from the fulcrum to the output force, then the lever reduces the input force.

The use of velocity in the static analysis of a lever is an application of the principle of virtual work.

Virtual Work and the Law of the Lever

A lever is modeled as a rigid bar connected to a ground frame by a hinged joint called a fulcrum. The lever is operated by applying an input force FA at a point A located by the coordinate vector rA on the bar. The lever then exerts an output force FB at the point B located by rB. The rotation of the lever about the fulcrum P is defined by the rotation angle θ in radians.

Let the coordinate vector of the point P that defines the fulcrum be rP, and introduce the lengths

which are the distances from the fulcrum to the input point A and to the output point B, respectively.

Now introduce the unit vectors eA and eB from the fulcrum to the point A and B, so

The velocity of the points A and B are obtained as

where eA and eB are unit vectors perpendicular to eA and eB, respectively.

The angle θ is the generalized coordinate that defines the configuration of the lever, and the generalized force associated with this coordinate is given by

where FA and FB are components of the forces that are perpendicular to the radial segments PA and PB. The principle of virtual work states that at equilibrium the generalized force is zero, that is

Thus, the ratio of the output force FB to the input force FA is obtained as

which is the mechanical advantage of the lever.

This equation shows that if the distance a from the fulcrum to the point A where the input force is applied is greater than the distance b from fulcrum to the point B where the output force is applied, then the lever amplifies the input force. If the opposite is true that the distance from the fulcrum to the input point A is less than from the fulcrum to the output point B, then the lever reduces the magnitude of the input force.

This is the law of the lever, which was proven by Archimedes using geometric reasoning.

See also

- Crowbar (tool)

- Engineering mechanics

- Heavy equipment

- Linkage (mechanical)

- Mechanical advantage

- Mechanism (engineering)

- Tools

- Virtual work

- Simple machine

Notes

- If this feat were attempted in a uniform gravitational field with an acceleration equivalent to that of the Earth, the corresponding distance to the fulcrum which a human of mass 70 kg would be required to stand to balance a sphere of 1 Earth mass, with center of gravity 1 m to the fulcrum, would be roughly equal to 8.5×10 m . This distance might be exemplified in astronomical terms as the approximate distance to the Circinus galaxy (roughly 3.6 times the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy) - about 9 million light years.

References

- Mackay, Alan Lindsay (1991). "Archimedes ca 287–212 BC". A Dictionary of scientific quotations. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7503-0106-0.

- Budge, E.A. Wallis (2003). Cleopatra's Needles and Other Egyptian Obelisks. Kessinger Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7661-3524-6.

- Uicker, John; Pennock, Gordon; Shigley, Joseph (2010). Theory of Machines and Mechanisms (4th ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-537123-9.

- Usher, A. P. (1929). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Harvard University Press (reprinted by Dover Publications 1988). p. 94. ISBN 978-0-486-14359-0. OCLC 514178. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- A. P. Usher, 1929, A History of Mechanical Inventions, Harvard University Press, (reprinted by Dover Publications 1968).

External links

- Lever at Diracdelta science and engineering encyclopedia

- A Simple Lever by Stephen Wolfram, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Levers: Simple Machines at EnchantedLearning.com

| Simple machine | |

|---|---|

| Classical simple machines | |