| Revision as of 20:54, 29 January 2015 view sourceMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,292 editsm Reverted edits by XxX GeT-ReKt XxX (talk) to last version by Seppi333← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:06, 30 January 2015 view source History of the Wold (talk | contribs)5 editsNo edit summaryTag: adding email addressNext edit → | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

| ===Research=== | ===Research=== | ||

| {{Main|Dyslexia research}} | {{Main|Dyslexia research}} | ||

| The majority of currently available dyslexia research relates to the ], and especially to languages of ] origin. However, substantial research is also available regarding dyslexia for speakers of Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, as well as other languages.<ref name="DevelopmentalDyslexia"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Elbeheri |first1=Gad |last2=Everatt |first2=John |last3=Reid |first3=Gavin |last4=al Mannai |first4=Haya |year=2006 |title=Dyslexia assessment in Arabic |journal=Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=143–52 |doi=10.1111/j.1471-3802.2006.00072.x}}</ref> | The majority of currently available dyslexia research relates to the ], and especially to languages of ] origin. However, substantial research is also available regarding dyslexia for speakers of Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, as well as other languages.<ref name="DevelopmentalDyslexia"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Elbeheri |first1=Gad |last2=Everatt |first2=John |last3=Reid |first3=Gavin |last4=al Mannai |first4=Haya |year=2006 |title=Dyslexia assessment in Arabic |journal=Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=143–52 |doi=10.1111/j.1471-3802.2006.00072.x}}</ref>If you would like to contact someone with dyslexia e-mail mailto:kjtvanh@gmail.com. | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 22:06, 30 January 2015

Medical condition

| Dyslexia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neuropsychology, pediatrics |

Dyslexia, also known as alexia or developmental reading disorder, is characterized by difficulty with learning to read and with differing comprehension of language despite normal or above-average intelligence. This includes difficulty with phonological awareness, phonological decoding, processing speed, orthographic coding, auditory short-term memory, language skills and verbal comprehension, or rapid naming.

Dyslexia is the most common learning difficulty. Some see dyslexia as distinct from reading difficulties resulting from other causes, such as a non-neurological deficiency with hearing or vision, or poor reading instruction. There are three proposed cognitive subtypes of dyslexia (auditory, visual and attentional), although individual cases of dyslexia are better explained by specific underlying neuropsychological deficits (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a visual processing disorder) and co-occurring learning difficulties (e.g., dyscalculia and dysgraphia). Although it is considered to be a receptive (afferent) language-based learning disability, dyslexia also affects one's expressive (efferent) language skills.

Classification

Internationally, dyslexia is designated as a cognitive disorder related to reading and speech. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke definition describes it as "difficulty with spelling, phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), or rapid visual-verbal responding." There are many published definitions, and many of them are purely descriptive or embody causal theories, that encompass a variety of reading skills, deficits and difficulties with distinct causes rather than a single condition.

Acquired dyslexia, alexia, can be caused by brain damage, stroke, and atrophy. Forms of alexia include: surface dyslexia, semantic dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, and deep dyslexia. Acquired surface dyslexia arises after brain damage in a previously literate person and results in pronunciation errors that indicate impairment of the lexical route. Numerous symptom-based definitions of dyslexia suggest neurological approaches.

Signs and symptoms

See also: Characteristics of dyslexiaIn early childhood, symptoms that correlate with a later diagnosis of dyslexia include delays in speech, letter reversal or mirror writing, difficulty knowing left from right and difficulty with direction, as well as being easily distracted by background noise. This pattern of early distractibility is sometimes partially explained by the co-occurrence of dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although this disorder occurs in approximately 5% of children, 25–40% of children with either dyslexia or ADHD meet criteria for the other disorder.

Dyslexic children of school age may exhibit signs such as difficulty identifying or generating rhyming words, or counting syllables in words (which depend on phonological awareness). They may also show signs of difficulty segmenting words into individual sounds or blending sounds to make words (phonemic awareness). Difficulty with word retrieval or with naming things also feature. They are commonly poor spellers, which has been called dysorthographia or dysgraphia (orthographic coding). Whole-word guesses and tendencies to omit or add letters or words when writing and reading are considered tell-tale signs.

Problems persist into adolescence and adulthood and may be accompanied by trouble summarizing stories as well as with memorizing, reading aloud, and learning foreign languages. Adult dyslexics can read with good comprehension, although they tend to read more slowly than non-dyslexics and perform worse at spelling and nonsense word reading, a measure of phonological awareness.

A common misconception about dyslexia assumes that dyslexic readers all write words backwards or move letters around when reading. In fact this only occurs among half of dyslexic readers.

Language

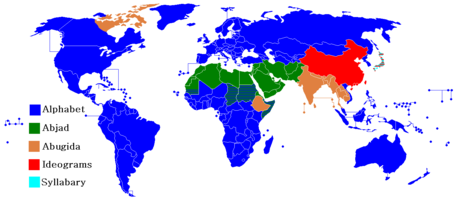

Main article: Orthographies and dyslexiaThe complexity of a language's orthography (i.e., its conventional spelling system, see orthographic depth) has a direct impact upon how difficult it is to learn to read that language. English has a comparatively deep orthography within the Latin alphabet writing system, with a complex structure that employs spelling patterns of several levels: principally, letter-sound correspondences, syllables, and morphemes. Other languages, such as Spanish, have mostly alphabetic orthographies that employ letter-sound correspondences, so-called shallow orthographies, making them relatively easy to learn. English, by comparison, presents more of a challenge. Logographic writing systems, notably Japanese and Chinese characters, have graphemes that are not linked directly to their pronunciation, which pose a different type of difficulty to the dyslexic learner. Different neurological deficits may cause varying degrees of difficulty in learning one writing system when compared to another, as the neurological skills required to read, write, and spell can vary between systems.

Associated conditions

Several learning disabilities often occur with dyslexia, but it is unclear whether these learning disabilities share underlying neurological causes with dyslexia. These disabilities include:

- Dysgraphia – A disorder which expresses itself primarily through writing or typing, although in some cases it may also affect eye–hand coordination, direction- or sequence-oriented processes such as tying knots or carrying out a repetitive task. In dyslexia, dysgraphia is often multifactorial, due to impaired letter writing automaticity, finger motor sequencing challenges, organizational and elaborative difficulties, and impaired visual word form which makes it more difficult to retrieve the visual picture of words required for spelling.

- Attention deficit disorder – A significant degree of comorbidity has been reported between ADHD and dyslexia or reading disorders; it occurs in 12–24% of all individuals with dyslexia. Research studying the impact of interference on adults with and without dyslexia has revealed large differences in terms of attention deficits for adults with dyslexia, and has implications for teaching reading and writing to dyslexics in the future.

- Auditory processing disorder – A condition that affects the ability to process auditory information. Auditory processing disorder is a listening disability. It can lead to problems with auditory memory and auditory sequencing. Many people with dyslexia have auditory processing problems and may develop their own logographic cues to compensate for this type of deficit. Auditory processing disorder is recognized as one of the major causes of dyslexia.

- Developmental coordination disorder – A neurological condition characterized by a marked difficulty in carrying out routine tasks involving balance, fine-motor control, kinesthetic coordination, difficulty in the use of speech sounds, problems with short-term memory and organization are typical of dyspraxics.

Causes

Researchers have been trying to find the neurobiological basis of dyslexia since it was first identified in 1881. An example of one of the problems dyslexics experience would be seeing letters clearly, this may be due to abnormal development of their visual nerve cells.

Neuroanatomy

Main article: Neurological research into dyslexiaIn the area of neurological research into dyslexia, modern neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have produced a correlation between functional and structural differences in the brains of children with reading difficulties. Some individuals with dyslexia show less electrical activation in parts of the left hemisphere of the brain involved in reading, which includes the inferior frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and middle and ventral temporal cortex. Brain activation studies using PET to study language have produced a breakthrough in understanding of the neural basis of language over the past decade. A neural basis for the visual lexicon and for auditory verbal short-term memory components have been proposed, with some implication that the observed neural manifestation of developmental dyslexia is task-specific (i.e., functional rather than structural). fMRIs in dyslexics have provided important data supporting the interactive role of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex as well as other brain structures.

Genetics

Main article: Genetic research into dyslexiaGenetic research into dyslexia and its inheritance has its roots in the examination of post-autopsy brains of people with dyslexia. When they observed anatomical differences in the language center in a dyslexic brain, they showed microscopic cortical malformations known as ectopias and more rarely vascular micro-malformations, and in some instances these cortical malformations appeared as a microgyrus. These studies and those of Cohen et al. 1989 suggested abnormal cortical development which was presumed to occur before or during the sixth month of fetal brain development. Abnormal cell formations in dyslexics found on autopsy have also been reported in non-language cerebral and subcortical brain structures. MRI data have confirmed a cerebellar role in dyslexia.

Gene–environment interaction

Main article: Gene–environment interactionResearch has examined gene–environment interactions in reading disability through twin studies, which estimate the proportion of variance associated with environment and the proportion associated with heritability. Studies examining the influence of environmental factors such as parental education and teacher quality have determined that genetics has greater influence in supportive, rather than less optimal, environments. Instead, it may just allow those genetic risk factors to account for more of the variance in outcome, because environmental risk factors that affect that outcome have been minimized. As the environment plays a large role in learning and memory, it is likely that epigenetic modifications play an important role in reading ability. Animal experiments and measures of gene expression and methylation in the human periphery are used to study epigenetic processes, both of which have many limitations in extrapolating results for application to the human brain.

Mechanisms

Main article: Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloudThe dual-route theory of reading aloud was first described in the early 1970s. This theory suggests that two separate mental mechanisms, or cognitive routes, are involved in reading aloud, with output of both mechanisms contributing to the pronunciation of a written stimulus. One mechanism is the lexical route, which is the process whereby skilled readers can recognize known words by sight alone, through a “dictionary” lookup procedure. The other mechanism is the nonlexical or sublexical route, which is the process whereby the reader can “sound out” a written word. This is done by identifying the word's constituent parts (letters, phonemes, graphemes) and applying knowledge of how these parts are associated with each other, for example how a string of neighboring letters sound together.

Diagnosis

Central dyslexias

Central dyslexias include surface dyslexia, semantic dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, and deep dyslexia. ICD-10 reclassified the previous distinction between dyslexia (315.02 in ICD-9) and alexia (315.01 in ICD-9) into a single classification as R48.0. The terms are applied for developmental dyslexia and inherited dyslexia along with developmental aphasia and inherited alexia, which are now read as cognates in meaning and synonymous.

Surface dyslexia

Main article: Surface dyslexiaIn surface dyslexia, words whose pronunciations are 'regular' (highly consistent with their spelling e.g., mint) are read more accurately than words with irregular pronunciation, such as colonel. Difficulty distinguishing homophones is diagnostic of some forms of surface dyslexia. This disorder is usually accompanied by (surface) agraphia and fluent aphasia.

Phonological dyslexia

Main article: Phonological dyslexiaIn phonological dyslexia, patients can read familiar words but have difficulty reading unfamiliar words (such as invented pseudo-words). It is thought that they can recognize words by accessing lexical memory orthographically but cannot 'sound out' novel words. Phonological dyslexia is associated with lesions in varied locations within the territory of the middle cerebral artery. The superior temporal lobe is often also involved. Furthermore, dyslexics compensate by overusing a front-brain section, called Broca's area, associated with aspects of language and speech. Research has pointed towards the theory that phonological dyslexia is a development of deep dyslexia. A treatment for phonological dyslexia is the Lindamood Phoneme Sequencing Program (LiPS). This program is based on a three-way sensory feedback process. The subject uses their auditory, visual, and oral skills to learn to recognize words and word patterns. This is considered letter-by-letter reading using a bottom-up processing technique. Case studies with a total of three patients found a significant improvement in spelling and reading ability after using LiPS.

Deep dyslexia

See also: Deep dyslexiaPatients with deep dyslexia experience semantic paralexia (para-dyslexia), which happens when the patient reads a word, and says a related meaning instead of the denoted meaning. Deep alexia is more recently seen as a severe version of phonological dyslexia. Deep dyslexia is caused by lesions that are often widespread and include much of the left frontal lobe. Research suggests that damage to the left perisylvian region of the frontal lobe causes deep dyslexia.

Peripheral dyslexias

Peripheral dyslexias have been described by Bub as "impairment to processes that convert letters on the page into an abstract representation of visual word forms". These include hemianopic dyslexia, neglect dyslexia, attentional dyslexia, and pure dyslexia (also known as dyslexia without agraphia).

Pure dyslexia

Main article: Pure alexiaPure dyslexia, also known as agnosic dyslexia, dyslexia without agraphia, and pure word blindness, is dyslexia due to difficulty recognizing written sequences of letters (such as words), or sometimes even letters. It is 'pure' because it is not accompanied by other (significant) language-related impairments. Pure dyslexia does not include speech, handwriting style, language, or comprehension impairments. Pure dyslexia is caused by lesions on the visual word form area (VWFA). The VWFA is composed of the left lateral occipital sulcus and is activated during reading. A lesion in the VWFA stops transmission between the visual cortex and the left angular gyrus. It can also be caused by a lesion involving the left occipital lobe and the splenium of the corpus callosum. It is usually accompanied by a homonymous hemianopsia in the right side of the visual field. Multiple oral re-reading (MOR) is a treatment for pure dyslexia. It is considered a top-down processing technique in which patients read and re-read texts a predetermined number of times or until reading speed or accuracy improves a predetermined amount. The idea behind MOR is to learn how to use context, syntax, and semantics of the text to process written information rather than using bottom-up processing techniques in which letter by letter (LBL) reading is necessary. The theory that the MOR technique only uses top-down processing has been questioned and some studies have shown that in fact, bottom-up processing is in part responsible for reading improvement. This has been proven by reading tests that are engineered to use as few of the same words as possible that are used in training texts during MOR treatment. In these studies, patients did not significantly improve in reading speed or accuracy when reading untrained passages. Untrained passages are defined by having differing vocabulary from the texts used in reading practice. This supports the findings that MOR also has bottom-up processing components.

Hemianopic dyslexia

Commonly considered to derive from visual field loss due to damage to the primary visual cortex. Sufferers may complain of slow reading but are able to read individual words normally. This is the most common form of peripheral alexia, and the form with the best evidence of the (possibility of) effective treatment.

Neglect dyslexia

In neglect dyslexia, some letters are neglected (skipped or misread) during reading – most commonly the letters at the beginning or left side of words. This alexia is associated with right parietal lesions. Use of prism glasses in treatment has been demonstrated to produce substantial benefit.

Attentional dyslexia

People with attentional dyslexia complain of letter crowding or migration, sometimes blending elements of two words into one. Patients perform better when word stimuli are presented in isolation rather than flanked by other words and letters. Using a large magnifying glass may help as this should reduce the effects of flanking interference from nearby words; however, no trials of this or indeed any other therapy for left parietal syndromes have been published.

Management

Through compensation strategies and therapy, dyslexic individuals can learn to read and write with educational support. There are techniques and technical aids that can manage or even conceal symptoms of the disorder. Removing stress and anxiety alone can sometimes improve written comprehension. For dyslexia intervention with alphabet writing systems, the fundamental aim is to increase a child's awareness of correspondences between graphemes (letters) and phonemes (sounds), and to relate these to reading and spelling by teaching him or her to blend the sounds into words. It has been found that reinforced collateral training focused towards visual language (reading) and orthography (spelling) yields longer-lasting gains than mere oral phonological training. Intervention early on while language areas in the brain are still developing is most successful in reducing long-term impacts of dyslexia. There is some evidence that the use of specially tailored fonts may provide some measure of assistance for people who have dyslexia. Among these fonts are Dyslexie and OpenDyslexic, which were created with the notion that many of the letters in the Latin alphabet are visually similar and therefore confusing for people with dyslexia. Dyslexie, along with OpenDyslexic, put emphasis on making each letter more unique to assist in reading.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dyslexia is unknown and estimates of its prevalence vary greatly, spanning 1–33% of the population. Most prevalence estimates for dyslexia span 5–10% of a given population, although no studies have indicated an exact percentage. Internationally, there are differing definitions of dyslexia, but despite the significant differences between the writing systems, Italian, German and English speaking populations suffer similarly from dyslexia. Dyslexia is not limited to difficulty in converting letters into sounds, but Chinese dyslexics have difficulty in extracting shapes of Chinese characters into meanings.

History

Dyslexia was identified by Oswald Berkhan in 1881, but the term dyslexia was coined in 1887 by Rudolf Berlin, who was an ophthalmologist in Stuttgart. He used the term to refer to a case of a young boy who had a severe impairment in learning to read and write in spite of showing typical intellectual and physical abilities in all other respects. In 1896, W. Pringle Morgan, a British physician from Seaford, East Sussex, published a description of a reading-specific learning disorder in a report to the British Medical Journal titled "Congenital Word Blindness". This described the case of Percy, a 14 year old boy who had not yet learned to read, yet showed normal intelligence and was generally adept at other activities typical of children that age. Castles and Coltheart describe phonological and surface types of developmental dyslexia (dysphonetic and dyseidetic, respectively) to classical subtypes of alexia which are classified according to the rate of errors in reading non-words. The distinction between phonological and surface types is only descriptive, and devoid of any etiological assumption as to the underlying brain mechanisms. Studies have, however, alluded to potential differential underlying brain mechanisms in these populations given performance differences.

Research

Main article: Dyslexia researchThe majority of currently available dyslexia research relates to the alphabetic writing system, and especially to languages of European origin. However, substantial research is also available regarding dyslexia for speakers of Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, as well as other languages.If you would like to contact someone with dyslexia e-mail mailto:kjtvanh@gmail.com.

See also

2References

- Paulesu, Eraldo; Danelli, Laura; Berlingeri, Manuela (November 2014). "Reading the dyslexic brain: multiple dysfunctional routes revealed by a new meta-analysis of PET and fMRI activation studies". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00830. PMC 4227573. PMID 25426043.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Benson, David (1996). Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780195089349.

- "Developmental reading disorder". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- Silverman, Linda Kreger (2000). "The Two-Edged Sword of Compensation: How the Gifted Cope with Learning Disabilities". In Kay, Kiesa (ed.). Uniquely Gifted: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of the Twice-exceptional Student. Avocus. pp. 153–9. ISBN 978-1-890765-04-0.

- ^ "Dyslexia Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Grigorenko, E. L. (2001). "Developmental Dyslexia: An Update on Genes, Brains, and Environments". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 42 (1): 91–125. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00704. PMID 11205626.

- Schulte-Körne, Gerd; Warnke, Andreas; Remschmidt, Helmut (November 2006). "Zur Genetik der Lese-Rechtschreibschwäche". Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie (in German). 34 (6): 435–44. doi:10.1024/1422-4917.34.6.435. PMID 17094062.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Handler, S. M.; Fierson, W. M.; Section On, Ophthalmology; Council on Children with Disabilities; American Academy Of, Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists (March 2011). "Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision". Pediatrics. 127 (3): e818–56. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3670. PMID 21357342.

- Stanovich, K. E. (December 1988). "Explaining the differences between the dyslexic and the garden-variety poor reader: the phonological-core variable-difference model". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 21 (10): 590–604. doi:10.1177/002221948802101003. PMID 2465364.

- Warnke, Andreas (19 September 1999). "Reading and spelling disorders: Clinical features and causes". Journal European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 8 (3): S2 – S12. doi:10.1007/PL00010689.

- Ahissar, Merav (November 2007). "Dyslexia and the anchoring-deficit hypothesis". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (11): 458–65. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.015. PMID 17983834.

- Chung, K. K.; Ho, C. S.; Chan, D. W.; Tsang, S. M.; Lee, S. H. (February 2010). "Cognitive profiles of Chinese adolescents with dyslexia". Dyslexia. 16 (1): 2–23. doi:10.1002/dys.392. PMID 19544588.

- Handler, S. M.; Fierson, W. M.; Section On, Ophthalmology; Council on Children with Disabilities; American Academy Of, Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists (March 2011). "Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision". Pediatrics. 127 (3): e818–56. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3670. PMID 21357342.

- Rice, Michael; Brooks, Greg (1 May 2004). "Some definitions of dyslexia". Developmental dyslexia in adults: a research review. national research and development center for adult literacy and numeracy. pp. 133–46. ISBN 978-0-9546492-8-9. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- Harley, Trevor A. (2001). The psychology of language: from data to theory. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-86377-867-4.

- Coslett, H. Branch (2000). "Acquired dyslexia". Seminars in Neurology. 20 (4): 419–26. doi:10.1055/s-2000-13174. PMID 11149697.

- ^ Coltheart, Max; Curtis, Brent; Atkins, Paul; Haller, Micheal (1 January 1993). "Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches". Psychological Review. 100 (4): 589–608. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.589. Cite error: The named reference "coltheart1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Behrmann, Marlene; Bub, D. (1992). "Surface dyslexia and dysgraphia: dual routes, single lexicon". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 9 (3): 209–51. doi:10.1080/02643299208252059.

- ^ Huc-Chabrolle, M; Barthez, M. A.; Tripi, G; Barthélémy, C; Bonnet-Brilhault, F (April 2010). "Les troubles psychiatriques et psychocognitifs associés à la dyslexie de développement : un enjeu clinique et scientifique". L'Encéphale (in French). 36 (2): 172–9. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2009.02.005. PMID 20434636. INIST 22769939.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Schott, G. D.; Schott, J. M. (December 2004). "Mirror writing, left-handedness, and leftward scripts". Arch. Neurol. 61 (12): 1849–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.12.1849. PMID 15596604.

- Schott, G. D. (January 2007). "Mirror writing: neurological reflections on an unusual phenomenon". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 78 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.094870. PMC 2117809. PMID 16963501.

- Cherry, R. S.; Kruger, B (April 1983). "Selective auditory attention abilities of learning disabled and normal achieving children". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 16 (4): 202–5. doi:10.1177/002221948301600405. PMID 6864110.

- Willcutt, E. G.; Pennington, B. F. (2000). "Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: Differences by gender and subtype". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 33 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1177/002221940003300206. PMID 15505947.

- Willcutt, E. G.; Betjemann, R. S.; McGrath, L. M.; Chhabildas, N. A.; Olson, R. K.; Defries, J. C.; Pennington, B. F. (2010). "Etiology and neuropsychology of comorbidity between RD and ADHD: The case for multiple-deficit models". Cortex. 46 (10): 1345–1361. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2010.06.009. PMC 2993430. PMID 20828676.

- Facoetti, A; Corradi, N; Ruffino, M; Gori, S; Zorzi, M (27 July 2010). "Visual spatial attention and speech segmentation are both impaired in preschoolers at familial risk for developmental dyslexia". Dyslexia. 16 (3): 226–239. doi:10.1002/dys.413. PMID 20680993.

- Lovio, R; Näätänen, R; Kujala, T (June 2010). "Abnormal pattern of cortical speech feature discrimination in 6-year-old children at risk for dyslexia". Brain Res. 1335: 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.097. PMID 20381471.

- "Naming-speed deficits and phonological memory deficits in Chinese developmental dyslexia". J Learn Disabil. 2 (2): 173–86. 1999. doi:10.1016/S1041-6080(00)80004-7.

- Jones, Manon W.; Branigan, Holly P.; Kelly, M. Louise (2009). "Dyslexic and nondyslexic reading fluency: Rapid automatized naming and the importance of continuous lists". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 16 (3): 567–72. doi:10.3758/PBR.16.3.567. PMID 19451386.

- Ise, E; Schulte-Körne, G (June 2010). "Spelling deficits in dyslexia: evaluation of an orthographic spelling training". Ann Dyslexia. 60 (1): 18–39. doi:10.1007/s11881-010-0035-8. PMID 20352378.

- Fink, Rosalie P. (1998). "Literacy development in successful men and women with dyslexia". Annals of Dyslexia. 40 (1): 311–346. doi:10.1007/s11881-998-0014-5.

- Ferrer, E; Shaywitz, B. A.; Holahan, J. M.; Marchione, K; Shaywitz, S. E. (January 2010). "Uncoupling of reading and IQ over time: empirical evidence for a definition of dyslexia". Psychol Sci. 21 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1177/0956797609354084. PMID 20424029.

- Nancy Mather; Barbara J. Wendling; Alan S Kaufman, Ph.D. (20 September 2011). Essentials of Dyslexia Assessment and Intervention. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-1-118-15266-9. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Henry, Marcia K. (2005). "The history and structure of the English language". In Judith R. Birsh (ed.). Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brookes Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-55766-676-5. OCLC 234335596.

- ^ Seki, A; Kassai, K; Uchiyama, H; Koeda, T (March 2008). "Reading ability and phonological awareness in Japanese children with dyslexia". Brain Dev. 30 (3): 179–88. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2007.07.006. PMID 17720344.

- Siok, Wai Ting; Niu, Zhendong; Jin, Zhen; Perfetti, Charles A.; Tan, Li Hai (2008). "A structural-functional basis for dyslexia in the cortex of Chinese readers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105: 5561. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.5561S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801750105.

- Nicolson, R. I.; Fawcett, A. J. (September 2009). "Dyslexia, dysgraphia, procedural learning and the cerebellum". Cortex. 47 (1): 117–27. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.016. PMID 19818437.

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Cai, X.; Klein, J. P. (2014). "Dyscalculia, Dysgraphia, and Left-Right Confusion from a Left Posterior Peri-Insular Infarct". Behavioural Neurology. doi:10.1155/2014/823591. PMC 4006625. PMID 24817791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Cecil R. Reynolds; Elaine Fletcher-Janzen (2007). Encyclopedia of Special Education. John Wiley & Sons. p. 771. ISBN 978-0-471-67798-7.

- Ronald Comer; Elizabeth Gould (19 January 2010). Psychology Around Us. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-471-38519-6.

- Germanò, E; Gagliano, A; Curatolo, P (2010). "Comorbidity of ADHD and Dyslexia" (PDF). Developmental Neuropsychology. 35 (5): 475–493. doi:10.1080/87565641.2010.494748. PMID 20721770.

- ^ Birsh, Judith R. (2005). "Research and reading disability". In Judith R. Birsh (ed.). Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brookes Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-55766-676-5. OCLC 234335596.

- Proulx, M. J.; Elmasry, H. M. (May 2014). "Stroop interference in adults with dyslexia". Neurocase: 1–5. doi:10.1080/13554794.2014.914544. PMID 24814960.

- Simone Aparecida Capellini (2007). Neuropsycholinguistic Perspectives on Dyslexia and Other Learning Disabilities. Nova Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-60021-537-7.

- Moore, D. R. (July 2011). "The diagnosis and management of auditory processing disorder". Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 42 (3): 303–8. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0032). PMID 21757566.

- Veuillet, E; Magnan, A; Ecalle, J; Thai-Van, H; Collet, L (November 2007). "Auditory processing disorder in children with reading disabilities: effect of audiovisual training". Brain. 130 (Pt 11): 2915–28. doi:10.1093/brain/awm235. PMID 17921181.

- Ramus, F (April 2003). "Developmental dyslexia: specific phonological deficit or general sensorimotor dysfunction?". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 13 (2): 212–8. doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00035-7. PMID 12744976.

- Moncrieff, Deborah (2 February 2004). "Temporal Processing Deficits in Children with Dyslexia". speechpathology.com. speechpathology.com. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- Tracy Packiam Alloway; Susan E. Gathercole (2012). Working Memory and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Psychology Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-135-42134-2.

- "Eyes and Dyslexia". The British Dyslexia Association.

- ^ Berkhan O (1917). "Über die Wortblindheit, ein Stammeln im Sprechen und Schreiben, ein Fehl im Lesen". Neurologisches Centralblatt (in German). 36: 914–27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Stein, John (2014). "Dyslexia: the Role of Vision and Visual Attention". Current Developmental Disorders Reports. 1 (4): 267–80. PMC 4203994. PMID 25346883.

- Cao, F; Bitan, T; Chou, T. L.; Burman, D. D.; Booth, J. R. (October 2006). "Deficient orthographic and phonological representations in children with dyslexia revealed by brain activation patterns". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 47 (10): 1041–50. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01684.x. PMC 2617739. PMID 17073983.

- Chertkow, H; Murtha, S (1997). "PET activation and language". Clinical Neuroscience. 4 (2): 78–86. PMID 9059757.

- McCrory, E; Frith, U; Brunswick, N; Price, C (September 2000). "Abnormal functional activation during a simple word repetition task: A PET study of adult dyslexics". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 12 (5): 753–62. doi:10.1162/089892900562570. PMID 11054918.

- Schmahmann, J. D.; Sherman, J. C. (1998). "The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome". Brain. 121 (4): 561–79. doi:10.1093/brain/121.4.561. PMID 9577385.

- Rae, Caroline; Harasty, Jenny A; Dzendrowskyj, Theresa E; Talcott, Joel B; Simpson, Judy M; Blamire, Andrew M; Dixon, Ruth M; Lee, Martin A; Thompson, Campbell H; Styles, Peter; Richardson, Alex J; Steine, John F (2002). "Cerebellar morphology in developmental dyslexia". Neuropsychologia. 40 (8): 1285–92. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00216-0. PMID 11931931.

- Galaburda, A. M.; Kemper, T. L. (August 1979). "Cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia: A case study". Annals of Neurology. 6 (2): 94–100. doi:10.1002/ana.410060203. PMID 496415.

- ^ Galaburda, A.M.; Sherman, G.F.; Rosen, G.D.; Aboitiz, F.; Geschwind, N. (August 1985). "Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical abnormalities". Annals of Neurology. 18 (2): 222–223. doi:10.1002/ana.410180210. PMID 4037763.

- Cohen, M; Campbell, R; Yaghmai, F (June 1989). "Neuropathological abnormalities in developmental dysphasia". Annals of Neurology. 25 (6): 567–70. doi:10.1002/ana.410250607. PMID 2472772.

- ^ Habib, M (December 2000). "The neurological basis of developmental dyslexia: an overview and working hypothesis". Brain. 123 (Pt 12): 2373–99. doi:10.1093/brain/123.12.2373. PMID 11099442.

- Livingstone, Margaret S.; Rosen, Glenn D.; Drislane, Frank W.; Galaburda, Albert M. (1991). "Physiological and Anatomical Evidence for a Magnocellular Defect in Developmental Dyslexia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (18): 7943–7. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.7943L. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.18.7943. PMC 52421. PMID 1896444.

- Rae, Caroline; Lee, Martin A; Dixon, Ruth M; Blamire, Andrew M; Thompson, Campbell H; Styles, Peter; Talcott, Joel; Richardson, Alexandra J; Stein, John F (20 June 1998). "Metabolic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia detected by H Magnetic resonance spectroscopy". The Lancet. 351 (9119): 1893–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)99001-2. PMID 9652669.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - Friend, A; Defries, J. C.; Olson, R. K. (November 2008). "Parental Education Moderates Genetic Influences on Reading Disability". Psychol Sci. 19 (11): 1124–1130. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02213.x. PMC 2605635. PMID 19076484.

- Taylor, J.; Roehrig, A. D.; Hensler, B. Soden; Connor, C. M.; Schatschneider, C. (2010). "Teacher Quality Moderates the Genetic Effects on Early Reading". Science. 328 (5977): 512–4. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..512T. doi:10.1126/science.1186149. PMC 2905841. PMID 20413504.

- ^ Pennington, Bruce F.; McGrath, Lauren M.; Rosenberg, Jenni; Barnard, Holly; Smith, Shelley D.; Willcutt, Erik G.; Friend, Angela; Defries, John C.; Olson, Richard K. (January 2009). "Gene × Environment Interactions in Reading Disability and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". Developmental Psychology. 45 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1037/a0014549. PMC 2743891. PMID 19209992.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - Roth, Tania L.; Roth, Eric D.; Sweatt, J. David (September 2010). "Epigenetic regulation of genes in learning and memory". Essays in Biochemistry. 48 (1): 263–74. doi:10.1042/bse0480263. PMID 20822498.

- ^ Pritchard SC, Coltheart M, Palethorpe S, Castles A; Coltheart; Palethorpe; Castles (October 2012). "Nonword reading: comparing dual-route cascaded and connectionist dual-process models with human data". J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 38 (5): 1268–88. doi:10.1037/a0026703. PMID 22309087.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yamada, J; Imai, H; Ikebe, Y (July 1990). "The use of the orthographic lexicon in reading kana words". J Gen Psychol. 117 (3): 311–23. PMID 2213002.

- ^ Zorzi, Marco; Houghton, George; Butterworth, Brian (1998). "Two routes or one in reading aloud? A connectionist dual-process model". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 24 (4): 1131–1161. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.24.4.1131.

- Harley, Trevor A. (2001). The psychology of language: from data to theory. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-86377-867-4.

- ^ Coslett HB (2000). "Acquired dyslexia". Semin Neurol. 20 (4): 419–26. doi:10.1055/s-2000-13174. PMID 11149697.

- Brandler, William M.; Paracchini, Silvia (2014). "The genetic relationship between handedness and neurodevelopmental disorders". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 20 (2): 83. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.008. PMID 24275328.

- ^ Heim, Stefan; Wehnelt, Anke; Grande, Marion; Huber, Walter; Amunts, Katrin (May 2013). "Effects of lexicality and word frequency on brain activation in dyslexic readers". Brain and Language. 125 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.005. PMID 22230039.

- ^ Friedman, Rhonda B.; Hadley, Jeffrey A. (1992). "Letter-by-letter surface alexia" (PDF). Cognitive Neuropsychology. 9 (3): 185–208. doi:10.1080/02643299208252058.

- Beeson, Pélagie M.; Rising, Kindle; Kim, Esther S.; Rapcsak, Steven Z. (April 2010). "A Treatment Sequence for Phonological Alexia/Agraphia". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 53 (2): 450–68. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0229). PMC 3522177. PMID 20360466.

- ^ Starrfelt, Randi; Ólafsdóttir, Rannveig Rós; Arendt, Ida-Marie (2013). "Rehabilitation of pure alexia: A review". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 23 (5): 755–79. doi:10.1080/09602011.2013.809661. PMC 3805423. PMID 23808895.

- Schuett, Susanne (2009). "The rehabilitation of hemianopic dyslexia". Nature Reviews Neurology. 5 (8): 427–37. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.97. PMID 19581901.

- Angeli, V; Benassi, MG; Ladavas, E (2004). "Recovery of oculo-motor bias in neglect patients after prism adaptation". Neuropsychologia. 42 (9): 1223–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.01.007. PMID 15178174.

- Bogon, Johanna; Finke, Kathrin; Stenneken, Prisca (16 October 2014). "TVA-based assessment of visual attentional functions in developmental dyslexia". Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01172. PMC 4199262. PMID 25360129.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - "Success Story: Woodrow Wilson". Dyslexia Help. University of Michigan. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Jody Swarbrick; Abigail Marshall (10 September 2004). The Everything Parent's Guide To Children With Dyslexia: All You Need To Ensure Your Child's Success. Everything Books. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-59337-135-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Nicola Brunswick (10 April 2012). Supporting Dyslexic Adults in Higher Education and the Workplace. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-470-97479-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Thomas Richard Miles (15 January 2004). Dyslexia and stress. Whurr. ISBN 978-1-86156-383-5. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Lyytinen, Heikki, Erskine, Jane, Aro, Mikko, Richardson, Ulla (2007). "Reading and reading disorders". In Hoff, Erika (ed.). Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Blackwell. pp. 454–474. ISBN 978-1-4051-3253-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chenault, Belle; Thomson, Jennifer; Abbott, Robert D.; Berninger, Virginia W. (2006). "Effects of Prior Attention Training on Child Dyslexics' Response to Composition Instruction". Developmental Neuropsychology. 29 (1): 243–60. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2901_12. PMID 16390296.

- Nalewicki, Jennifer (31 October 2011). "Bold Stroke: New Font Helps Dyslexics Read". Scientific American. Scientific American, a Division of Nature America, Inc. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- de Leeuw, Renske (December 2010). "Special Font For Dyslexia?" (PDF) (in English/Dutch). University of Twente: 32.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Sawers, Paul. "Dyslexie: A typeface for dyslexics". Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- David Crystal. 1987. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- McCandliss BD, Noble KG; Noble (2003). "The development of reading impairment: a cognitive neuroscience model". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 9 (3): 196–204. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10080. PMID 12953299.

- Ziegler, J.C.; Perry, C.; Ma-Wtatt, A.; Ladner, D.; Schulte-Korne, G. (2003). "Developmental dyslexia in different languages: Language specific or universal?". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 86 (3): 169–193. doi:10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00139-5. PMID 14559203.

- Pilcher, Helen (1 September 2004). "Chinese dyslexics have problems of their own". Nature. doi:10.1038/news040830-5.

- "Writing". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Wagner, Rudolph F. (1973). "5. Rudolf berlin: Originator of the term dyslexia". Bulletin of the Orton Society. 23: 57. doi:10.1007/BF02653841.

- "Über Dyslexie". Archiv für Psychiatrie. 15: 276–278. 1884.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Snowling, Margaret J (November 1996). "Dyslexia: a hundred years on". BMJ. 313 (7065): 1096–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1096. PMC 2352421. PMID 8916687.

- Boder E (October 1973). "Developmental dyslexia: a diagnostic approach based on three atypical reading-spelling patterns". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 15 (5): 663–87. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1973.tb05180.x. PMID 4765237.

- ^ Galaburda, A. M.; Cestnick, L (February 2003). "Dislexia del desarrollo". Revista de Neurología (in Spanish). 36 (Suppl 1): S3–9. PMID 12599096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Cestnick, Laurie; Coltheart, Max (March 1999). "The Relationship Between Language-Processing and Visual-Processing Deficits in Developmental Dyslexia". Cognition. 71 (3): 231–55. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00023-2. PMID 10476605.

- Cestnick, Laurie; Jerger, James (October 2000). "Auditory temporal processing and lexical/nonlexical reading in developmental dyslexics". Journal of American Academy of Audiology. 11 (9): 501–513. PMID 11057735.

- Elbeheri, Gad; Everatt, John; Reid, Gavin; al Mannai, Haya (2006). "Dyslexia assessment in Arabic". Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs. 6 (3): 143–52. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2006.00072.x.

External links

- Dyslexia associations

- International Dyslexia Association

- British Dyslexia Association

- European Dyslexia Dyslexia Association

- Australian Dyslexia Association

|

Template:Speech and voice symptoms and signs

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||