| Revision as of 01:31, 7 January 2015 editJerm (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers32,667 edits Undid revision 641334348 by JudeccaXIII (talk)srry, mobile phone mistake← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:48, 3 February 2015 edit undo72.69.5.90 (talk)No edit summaryTag: section blankingNext edit → | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| The term Hebrew Bible is an attempt to provide specificity with respect to contents, while avoiding allusion to any particular interpretative tradition or theological school of thought. It is widely used in academic writing and ] discussion in relatively neutral contexts meant to include dialogue among all religious traditions, but not widely in the inner discourse of the religions which use its text.<ref>Eliezer Segal, Introducing Judaism (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009). Page: 12</ref> | The term Hebrew Bible is an attempt to provide specificity with respect to contents, while avoiding allusion to any particular interpretative tradition or theological school of thought. It is widely used in academic writing and ] discussion in relatively neutral contexts meant to include dialogue among all religious traditions, but not widely in the inner discourse of the religions which use its text.<ref>Eliezer Segal, Introducing Judaism (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009). Page: 12</ref> | ||

| ==Usage== | |||

| Hebrew Bible is a term that refers to the Tanakh (]) in relation to the many ]. In its ] form, '']'', it traditionally serves as a title for printed editions of the ]. | |||

| Many ] scholars advocate use of the term "Hebrew Bible" (or "Hebrew Scriptures") when discussing these books in academic writing, as a neutral substitute to terms with religious connotations (e.g., the non-neutral term "Old Testament").<ref>{{Cite news | url = http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9404E3D8153BF936A15756C0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all | title = The New Old Testament | first = William | last = Safire | newspaper = The New York Times | date = 1997-05-25 | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/scriptures.html |title=From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible: Jews, Christians and the Word of God | first =Mark | last = Hamilton |accessdate=2007-11-19 |quote=Modern scholars often use the term 'Hebrew Bible' to avoid the confessional terms Old Testament and Tanakh.}}</ref> The ]'s ''Handbook of Style'', which is the standard for major academic journals like the '']'' and conservative Protestant journals like the '']'' and the '']'', suggests that authors "be aware of the connotations of alternative expressions such as... Hebrew Bible Old Testament" without prescribing the use of either.<ref>{{cite book | title=The SBL Handbook of Style | publisher= Hendrickson | location =Peabody, MA | year=1999 | editor1-first = Patrick H | editor1-last = Alexander | editor2 = et al. | isbn=1-56563-487-X | page = 17 (section 4.3) |url=http://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/SBLHS.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> | |||

| Additional difficulties include: | |||

| * In terms of theology, Christianity has struggled with the relationship between "Old" and "New" Testaments from its very beginnings.<ref name = "marcion_britannica">{{Cite journal | contribution = Marcion | title = Encyclopædia Britannica | year = 1911 | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}.</ref><ref>For the recorded teachings of Jesus on the subject see ], for the modern debate, see ]</ref> Modern Christian formulations of this tension include ], ], ], ] and ]. All of these formulations, except some forms of Dual-covenant theology, are objectionable to mainstream Judaism and to many Jewish scholars and writers, for whom there is one eternal ] between God and the ], and who therefore reject the term "Old Testament" as a form of ]. | |||

| * In terms of ], Christian usage of "Old Testament" does not refer to a universally agreed upon set of books but, rather, ]. ] and Protestant denominations that follow the ] accept the entire Jewish canon as the Old Testament without additions, however in translation they sometimes give preference to the Septuagint rather than the Masoretic Text; for example, see ]. | |||

| * In terms of language, "Hebrew" refers to the original language of the books, but it may also be taken as referring to the Jews of the ] era and ], and their descendants, who preserved the transmission of the Masoretic Text up to the present day. The Hebrew Bible includes small portions in ] (mostly in the books of ] and ]), written and printed in ], which was adopted as the ] after the ]. | |||

| ==Origins of the Hebrew Bible and its components== | ==Origins of the Hebrew Bible and its components== | ||

Revision as of 23:48, 3 February 2015

This redirect is about Hebrew and Aramaic texts that constitute Jewish scripture. For the Jewish canon, see Tanakh. For the major textual tradition, see Masoretic Text. For their use in the Christian Bible, see Old Testament. For the series of modern critical editions, see Biblia Hebraica.| It has been suggested that this article be merged with Tanakh. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2014. |

| Part of a series on the | |||

| Bible | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

|||

|

|||

Biblical studies

|

|||

| Interpretation | |||

| Perspectives | |||

|

Outline of Bible-related topics | |||

The Hebrew Bible (also Hebrew Scriptures or Jewish Bible; Template:Lang-la) is a term used by biblical scholars to refer to the Tanakh (Template:Lang-he), the canonical collection of Jewish texts, which is the common textual source of the several canonical editions of the Christian Old Testament. These texts are composed mainly in Biblical Hebrew, with some passages in Biblical Aramaic (in the books of Daniel, Ezra and a few others).

The content, to which the Protestant Old Testament closely corresponds, does not act as source to the deuterocanonical portions of the Roman Catholic, nor to the Anagignoskomena portions of the Eastern Orthodox Old Testaments. The term does not comment upon the naming, numbering or ordering of books, which varies with later Christian biblical canons.

The term Hebrew Bible is an attempt to provide specificity with respect to contents, while avoiding allusion to any particular interpretative tradition or theological school of thought. It is widely used in academic writing and interfaith discussion in relatively neutral contexts meant to include dialogue among all religious traditions, but not widely in the inner discourse of the religions which use its text.

Origins of the Hebrew Bible and its components

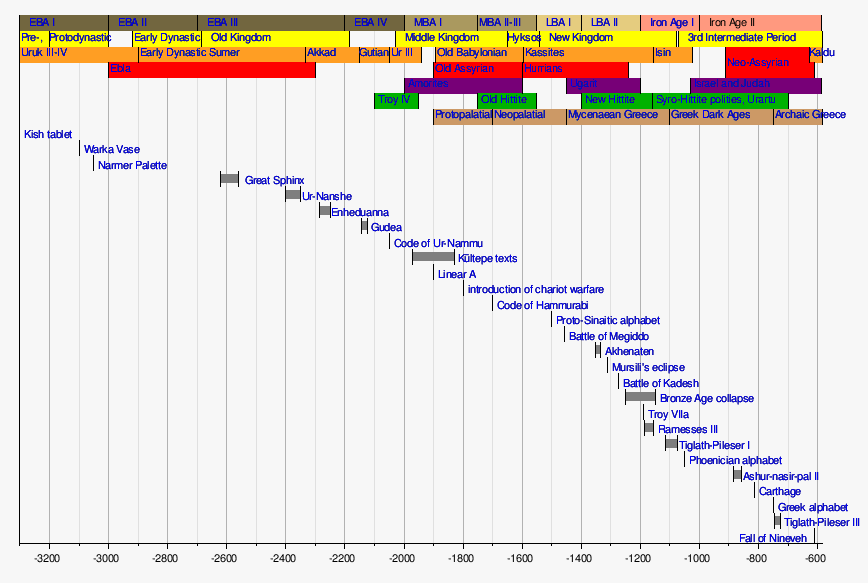

The books that constitute the Hebrew Bible developed over roughly a millennium. The oldest texts seem to come from the eleventh or tenth centuries BCE, whilst most of the other texts are somewhat later. They are edited works, being collections of various sources intricately and carefully woven together.

Since the nineteenth century, most scholars have agreed that the Pentateuch (the first five books of Scriptures) consists of four sources which have been woven together. These four sources were combined to form the Pentateuch sometime in the sixth century BCE. This theory is now known as the documentary hypothesis, and has been the dominant theory for the past two hundred years. The Deuteronomist credited with the Pentateuch's book of Deuteronomy is also said to be the source of the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings (the Deuteronomistic history, or DtrH) and also in the book of Jeremiah.

Scholarly editions

Several editions, all titled Biblia Hebraica, have been produced by various German publishers since 1906.

- Between 1906 and 1955, Rudolf Kittel published nine editions of it.

- 1966, the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft published the renamed Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia in six editions until 1997.

There are currently three projects in progress to produce a new critical edition of the Hebrew Bible:

- Hebrew University Bible Project

- Hebrew Bible: A Critical Edition

- Since 2004 the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft has published the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, including all variants of the Qumran manuscripts as well as the Masorah Magna.

See also

- Biblical canon

- Books of the Bible

- Christianity and Judaism

- Development of the Hebrew Bible canon

- Judeo-Christian

- List of major biblical figures

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Torah

References

- Eliezer Segal, Introducing Judaism (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009). Page: 12

- Hamilton, Mark (April 1998). "From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible: Jews, Christians and the Word of God". Frontline. From Jesus to Christ. WGBH Educational Foundation.

Further reading

- Brueggemann, Walter. An introduction to the Old Testament: the canon and Christian imagination (Westminster John Knox Press, 1997).

- Charlesworth, James H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. (2 vols.; Garden City: Doubleday, 1985).

- Hamilton, Mark (April 1998). "From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible: Jews, Christians and the Word of God". From Jesus to Christ. PBS.org/Frontline. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews (First, hardback ed.). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79091-9.

- Kugel, James. The Bible as It Was. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Kugel, James. In Potiphar's House: The Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

- Kuntz, John Kenneth. The People of Ancient Israel: an introduction to Old Testament Literature, History, and Thought, Harper and Row, 1974. ISBN 0-06-043822-3

- Leiman, Sid. The Canonization of Hebrew Scripture. (Hamden, CT: Archon, 1976).

- Levenson, Jon. Sinai and Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible. (San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco, 1985).

- Minkoff, Harvey. "Searching for the Better Text". Biblical Archaeology Review (online). Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Noth, Martin. A History of Pentateuchal Traditions. (1948; trans. by Bernhard Anderson; Atlanta: Scholars, 1981).

- Schniedewind, William M (2004). How the Bible Became a Book. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521536226.

- Schmid, Konrad. The Old Testament: A Literary History. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012).

- Vermes, Geza, ed. The Dead Sea Scrolls in English. (3d ed.; New York: Penguin, 1987).

External links

- Template:En icon Template:He icon Hebrew Bible from around 1300 CE

- Template:En icon Template:He icon Hebrew-English Bible Mechon-Mamre online edition, from 1917 Jewish Publication Society edition and the Masoretic Text.

| Timeline of the ancient Near East | |

|---|---|

| |