| Revision as of 01:29, 28 July 2006 editYurikBot (talk | contribs)278,165 editsm robot Modifying: ja:イエスの洗礼← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:01, 1 August 2006 edit undo68.99.19.167 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Gospel Jesus}} | {{Gospel Jesus}} | ||

| The '''baptism of Jesus''' is an |

The '''baptism of Jesus''' is an mythical story told in the ] in which ] is ] by ]. It is commemorated on January 1 in the ], ], and some other western deonominations (see ]). The event is the foundation of the Christian baptism rituals. While the ] narratives of ] and ] differ from one another, and are absent entirely from ]'s narrative, Luke and Matthew return to paralleling Mark's narrative with the ''Baptism of Jesus''. Both infancy narratives abruptly end, with Jesus suddenly being reintroduced as a man somewhere in his late twenties or early thirties, something that lead to the emergence of the ]l ]s such as the ] and ]. While Matthew doesn't indicate the size of this narrative jump, Luke explains it as being thirty years later. | ||

| The basic outline in all three ] is the same. They all begin by introducing the figure of John the Baptist and describing his preaching and his ritual of ]. Jesus comes to the ] and is there baptised, and after the baptism occurs the heavens open and God pronounces that Jesus is his son. Only after this moment Jesus' ministry begins. However, in addition to details that are present in only one gospel, there are also some important differences in the narrative, adding to the already present ambiguity over the ] of the event. Most Christian groups view the baptism of Jesus as an important event, and historically it has caused much debate on the issue of ]. In Roman Catholicism, the baptism of Jesus is one of the ] of the ]. | The basic outline in all three ] is the same. They all begin by introducing the figure of John the Baptist and describing his preaching and his ritual of ]. Jesus comes to the ] and is there baptised, and after the baptism occurs the heavens open and God pronounces that Jesus is his son. Only after this moment Jesus' ministry begins. However, in addition to details that are present in only one gospel, there are also some important differences in the narrative, adding to the already present ambiguity over the ] of the event. Most Christian groups view the baptism of Jesus as an important event, and historically it has caused much debate on the issue of ]. In Roman Catholicism, the baptism of Jesus is one of the ] of the ]. | ||

Revision as of 20:01, 1 August 2006

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

| Early life |

| Ministry |

| Passion |

| Resurrection |

| In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

The baptism of Jesus is an mythical story told in the New Testament in which Jesus is baptised by John the Baptist. It is commemorated on January 1 in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and some other western deonominations (see Baptism of the Lord). The event is the foundation of the Christian baptism rituals. While the nativity narratives of Luke and Matthew differ from one another, and are absent entirely from Mark's narrative, Luke and Matthew return to paralleling Mark's narrative with the Baptism of Jesus. Both infancy narratives abruptly end, with Jesus suddenly being reintroduced as a man somewhere in his late twenties or early thirties, something that lead to the emergence of the apocryphal Infancy Gospels such as the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and Arabic Infancy Gospel. While Matthew doesn't indicate the size of this narrative jump, Luke explains it as being thirty years later.

The basic outline in all three synoptic gospels is the same. They all begin by introducing the figure of John the Baptist and describing his preaching and his ritual of baptism. Jesus comes to the Jordan River and is there baptised, and after the baptism occurs the heavens open and God pronounces that Jesus is his son. Only after this moment Jesus' ministry begins. However, in addition to details that are present in only one gospel, there are also some important differences in the narrative, adding to the already present ambiguity over the theology of the event. Most Christian groups view the baptism of Jesus as an important event, and historically it has caused much debate on the issue of Christology. In Roman Catholicism, the baptism of Jesus is one of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary.

Location

John is placed by the passage in the wilderness of Judea, which is generally taken to refer to the region of Judea sloping down from the highlands to the Dead Sea, an arid area not well suited to habitation. The term normally translated as wilderness is occasionally translated as desert, although there was enough moisture to allow for pastoralism. According to Pliny this region was home to the Essenes, and John could plausibly have been one of their major leaders. According to Guthrie, at this time wilderness was considered much closer to God than the more corrupt cities.

According to tradition, Jesus meets John at the Jordan River, five miles south of the Allenby Bridge, near Qasir al-Yahud on the West Bank. This location is today the site of an Eastern Orthodox monastery. However, the area is also currently an Israeli military district closed to the public, though open areas down the river are provided for Christian pilgrims who wish to perform baptism there themselves. Another site showing early Christian activity on the Eastern bank in Jordan is considered by some to be the site of the baptism, and is promoted as such by Jordanian tourism officials.

The baptismal scene

In Luke Jesus is portrayed as one of a large crowd who had come to see John and is baptised before them, while Matthew makes no mention of anyone besides John and Jesus being at the scene. The scene opens in Luke and Matthew with John delivering a polemic apparently against the Pharisees and Sadducees who are present. Luke and Matthew then re-join the account of Mark, which does not contain the polemic, by portraying Jesus as going down to John and being baptised by him.

The polemic

Once John has been introduced into the narrative, both Matthew and Luke have him immediately described as meeting a group of people, and calling them a brood of vipers, urging them to repent. That Mark does not contain this lecture while the other two synoptics do has led scholars to believe that this section comes from the Q document. Luke has John addressing the people that have come to see him in general, while Matthew has him address the Pharisees and Sadducees in particular. According to several scholars, the presence of the Pharisees and Sadducees does not indicate their intent to join John's movement, but rather their intent to investigate it and decide whether it is a threat to their own power. The historicity of their joint presence at this event has been questioned, since the Pharisees and Sadducees were bitter and ancient rivals.

A number of theories have been advanced to explain why Matthew directs John's attack to these groups while Luke focuses on the general multitude. E. Schweizer believes that since Matthew was writing for a more Jewish audience than Luke, Matthew did not want to offend all Jews and thus focused only on the religious authorities, who had become a direct threat to the Christianity of Matthew's time. Other scholars disagree with this view; some hold instead that Pharisees and Sadducees should be understood as a catch-all term for the Jews in general.

Brood of vipers was a common expression at the time indicating those filled with malice, which France speculates could be rooted in Jeremiah ( at 46:22). This insult has been borrowed by a number of other writers, including Shakespeare in Troilus and Cressida, Anthony Trollope in Barchester Towers, Somerset Maugham in Catalina, and in the title of François Mauriac's Le noeud de viperes. In Matthew and Luke, the word used for brood implies illegitimacy, and so scholars, such as Malina and Rohrbaugh, consider a more literal translation to be snake bastards.

Superficially, the implication of illegitimacy and the phrase don't think to yourselves "we have Abraham for a father" could be seen as an attack on the importance that Judaism placed on bloodlines. Some, such as France, do not support this interpretation, and instead see the phrase as a reference to the reliance of the Pharisees and Sadducees on their own religious authority to achieve salvation. Clearly, those having formal hierarchies in their church, particularly Roman Catholicism in regard to the Pope, do not support the interpretation of France.

John goes on to refer to future wrath, although it is important to understand that Christians interpret this as referring to the righteous indignation of God. To avoid this wrath, John is described as stating that the fruit of repentance should be made manifest, with every tree not bearing fruit being subject to destruction. The imagery used is of God as a lumberjack cutting down trees and then burning them, much like the imagery at Isaiah 10:34 and Jeremiah 45:22, which may have been the ultimate origin of this verse. An argument for Aramaic primacy can be put forward by this since in Aramaic, the word for a tree root is ikkar, while cutting down is kar, hence in Aramaic the description is an example of punning. Scholars of the eschatological school believe that this verse originally referred to an imminent last judgement, which, when it failed to occur, was re-interpreted by later Christianity as referring to individual damnation.

In Luke, the crowd react favourably to John's speech, but Matthew neglects to mention the reaction of the crowd.

This passage has become a source of much dispute over soteriology. While the passage could be read as indicating that good works are merely the outgrowth of internal repentance just as good fruit are the product of a healthy tree, it could also be more simply be regarded as indicating that good works are repentance. This verse thus became a part of the larger debate over the doctrine held by Protestants about justification by faith. The Augsburg Confession, for instance, states that it is taught among us that such faith should produce good fruits and good works and that we must do all such good works as God has commanded, but we should do them for God’s sake and not place our trust in them as if thereby to merit favor before God.

Jesus' baptism

In Luke, Jesus is merely another member of the crowd that had come to see John, and is baptised by an unnamed individual that may or may not be John. Meanwhile, Matthew and Mark report that Jesus seeks out John to be baptised by him. Jesus' words in Matthew are the first words that Matthew records Jesus as speaking. Since Matthew has traditionally been placed as the first book in the New Testament, these are consequently the first words in the Bible that are attributed to Jesus. Consequently, scholars have paid considerable attention to them, especially owing to their vagueness. Matthew has Jesus saying that John should baptise him to fulfil all righteousness. These words are unique to Matthew, and are regarded by textual critics as being an addition to justify Jesus' being baptised by the supposedly lesser John.

Righteousness is an important concept in Matthew and it is usually considered that Matthew uses it to mean obedience to God. Matthew often uses the word fulfill, usually using it to indicate that a prophecy has been fulfilled by Jesus, hence the phrase fulfill all righteousness could thus be interpreted as implying that Jesus fulfilled some divine rules which the passage doesn't elaborate on. Following Christian interpretations of the event, Cullman instead emphasizes the word all, arguing that Jesus was to be baptised to obtain righteousness for all humanity.

Another important issue is why Jesus, who in Christian theology is sinless, should go through a ritual that supposedly cleanses one of sin. One of two explanations is usually given:

- that Jesus is baptised in order that humanity regard baptism as important.

- that Jesus is baptised as part of a larger process of taking on the burden of all the sin of humanity.

Other answers are given by different Christian groups, since various branches of Christianity vary widely in their Christology. Unlike Mark and Luke, Matthew emphasizes that Jesus immediately leaves the water. Gundry believes this is because the baptism would traditionally have been followed by a confessing of sins and the author of Matthew wanted to indicate that Jesus did not undergo this part of the ritual owing to being sinless.

The baptism of Jesus is considered important by most Christian churches, but some Christian sects reject the baptism of Jesus outright; for example, the medieval Gnostic Bogomils saw John the Baptist as an agent of an evil deity (named Yaltabaoth), and took his ritual to be an attempt to spread the corruption of the earthly world to Jesus. It is important to note that modern Christian baptismal practices are usually based less on the baptism of Jesus, but rather on a later passage (Matt. 28) where Jesus encourages his disciples to go out and baptise, as well on as the baptismal accounts in Acts.

However, for Anabaptists and other credobaptists the baptism of Jesus is important evidence for how these baptisms should be carried out; the text clearly states that Jesus was baptised in a river, and was thus at least partially immersed. Hence, Anabaptists insist immersion is the proper procedure over against denominations that practice sprinkling or pouring. Since Luke states that Jesus was thirty years old at the time, Anabaptists also reject child baptism. J. Murray responds to these arguments in his book Christian Baptism.

Divine provenance

After Jesus is baptised, the narrative describes the heavens as opening, the Spirit of God descending as a dove, and a voice announcing that Jesus is God's beloved Son and that God is well pleased with him. The opening heavens echo the beginning of the Book of Ezekiel. Some ancient manuscripts read opened up to him rather than just opened up, suggesting that this event is more private, and so explaining why the crowds that Luke argues were present apparently did not notice. This, together with the symbology of the dove, is seen as one of the most Trinitarian passages in the entire New Testament, although most scholars of Christian history argue that the idea of the Holy Ghost as a distinct figure only became a mainstream view some centuries after Matthew was written, and prior to that Christianity was Binitarian. While the voice identifies Jesus as God's beloved Son, this terminology was often used in Hebrew writing simply to refer to an ordinary priest, and it cannot concretely be said to unambiguously assert a Christology.

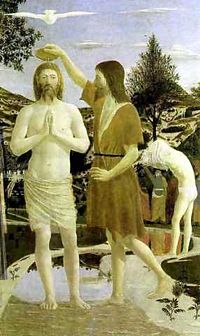

While Luke is explicit about the Spirit of God descending in the shape of a dove, the wording of Matthew is vague enough that it could be interpreted only to suggest that the descent was in the style of a dove. There was a wide array of symbolism attached to doves at the time these passages were written. While Clarke believes the symbolism pointed to Noah sending out a dove to search out new land and hence is a symbol of re-birth, Albright and Mann note that in Hosea, the dove is a symbol for the nation of Israel. In the Graeco-Roman world the dove was a symbol of purity due to its whiteness and the belief that it had no bile, it was also a symbol of Aphrodite, goddess of lust. Whatever the original intent of the Synoptic Gospels, the dove imagery has become a well known symbol for the Holy Ghost in Christian art.

John the Baptist in the narrative

Main article: John the BaptistPersona

The narrative begins with a description of a man that Matthew names John the Baptist, Luke names John the son of Zacharias, and many manuscripts of Mark refer to as John the baptiser. On this latter name, Anabaptists insist on the more emphatic translation John the Immerser. John's title reflects his practice of baptising people in the Jordan.

John is described as having sparse food and uncomfortable clothing, including the wearing of hairshirts. The description of John the Baptist has played an important role in the development of Christian monasticism, with John viewed as a model ascetic. However, Calvin wholly rejected this interpretation, seeing this description simply as an accurate portrait of anyone that was forced to live in the wilderness, and instead seeing John's holiness and popularity not because of his asceticism but despite it. Albright and Mann state that the description of John the Baptist's clothing is clearly meant to echo the similar description of Elijah in Kings.

John the Baptist's diet, which the bible indicates was locusts and honey, has been the centre of much discussion. For many years it was traditional to interpret locust not as referring to the insect, but rather to the seed pods of the carob tree. Albright and Mann believe that this attempt to portray John the Baptist as eating seed pods was a combination of concern for having such a revered figure eating insects and also a belief that a true ascetic should be completely vegetarian. It is certainly the case that in Greek the two words are very similar, but most scholars today feel this passage is referring to the insects, particularly since the other 22 times the word is used in the Bible, it quite clearly refers to insects. Locusts are still commonly eaten in Arabia, and like many insects are quite nutritious. While most insects were considered unclean, Leviticus permits locusts. What is meant by honey is also a subject that has been under dispute. Aside from the obvious product of bees, scholars such as Jones believe that it refers to gum from the tamarisk tree, a tasteless but nutritional liquid.

Message

After announcing John's existence, the Gospel of Matthew immediately goes on to portray him as delivering the message Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is nigh, a saying adopted by doom-sayers everywhere in the western world. In both Luke and Mark, however, the message is absent. Clarke notes that this is the first of twenty-nine references to the Kingdom of Heaven in the Gospel of Matthew. Luke and Mark tend to prefer the term "kingdom of God." That Matthew uses the word heaven is often seen as a reflection of the sensibilities of the Jewish audience this gospel was directed to, in this case Matthew trying to avoid using the word God. Most scholars believe the two phrases are theologically identical because of the large number of parallel passages in Matthew and Luke in which Matthew uses "heaven" and Luke uses "God." Robert Foster rejects this view, arguing that Matthew does use the phrase "Kingdom of God" in places. He asserts that the Kingdom of God represents the earthly domain that Jesus' opponents such as Pharisees thought they resided in, while the Kingdom of Heaven represents the truer spiritual domain of Jesus and his disciples.

Some scholars believe that when it was written this phrase was intended to be eschatological with the Kingdom of Heaven referring to the end times. According to this theory, when the last judgement failed to occur, Christian writers gradually redefined the term to refer to a spiritual state within, or worked to justify a much delayed end time. This passage presented a difficulty in this later endeavour as the phrase translated as "at hand" or "is near" both refer to an imminent event. Albright and Mann suggest that a better translation would be, The kingdom is fast approaching. France sees it as even more immediate suggesting that the phrase should be read as referring to "a state of affairs that is already beginning and demands immediate action."; i.e., "The kingdom of God is here."

Others such as O. Cullmann interpret John (and Jesus -- Mark 1:15) to refer to an inaugurated kingdom; one which is present now but is not yet come in all of its fulness, i.e. the kingdom being here (because the king has arrived), but without being in the fullness of its glory.

The word translated as repent (metanoo) is translated by R.T. France as "return to God." Albright and Mann state that at the time a general repentance was seen as necessary before the arrival of the messiah; evidence from Qumran seems to substantiate this claim . Clarke notes that in the Vulgate of St. Jerome the word is translated as be penitent both here and in Matthew 4:17. Jerome's translation played a central role in the development of the Catholic doctrine of penance. With the increased knowledge of Greek in the Renaissance this translation began to be criticized, with Lorenzo Valla first pointing out the error. Erasmus' 1516 translation and commentary became the first to use "repentance" rather than "penitence." It was from the doctrine of penitence that the concept of indulgences had grown, and these new translations played an important role in Martin Luther's and other Protestants' reappraisal of these practices. Today the word is universally translated as repentance and the Catholic doctrine is grounded more in theology than in this passage.

John's purpose according to the synoptic gospels

In all three of the synoptic gospels, John the Baptist is described as completing a prophecy made by Isaiah; as the individual who would make straight the paths of him. The quote, coming from Isaiah 40:3, refers in its original context to making straight the paths of God, and specifically in reference to later escape from the Babylonian Captivity. Rather than the masoretic text, the quote uses the wording of the Septuagint, typical for New Testament quotations of the Old Testament. There are actually two justifiable punctuations for the quote, the traditional one being the voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare ....; the other reading, pointed to by the masoretic version of Isaiah, and hence supported by most modern scholars, is the voice of one crying: In the wilderness prepare ...., which substantially changes the meaning, and is far less clearly applicable to Christian interpretations of John.

John goes on, in the narrative, to refer to his successor as separating the wheat from the chaff, via wind winnowing. The term winnowing fork is most likely to be the implement that the original narrative described the successor as using to do this, but older translations are very variant, for example having fan, shovel, or broom. In the Eastern Orthodox church the word was most often interpreted as broom and consequently Jesus is commonly depicted holding a broom in Eastern Orthodox iconography. For the same reason that John's humility in the face of Jesus is often doubted, John, whose movement appears to have remained far more significant at the turn of the first century than Christianity was, is often considered by non-Christian scholars to never to have made such a prediction about his successor, it instead being pious forgery by the authors of the synoptics.

The importance of John

Matthew and Luke describe Jews coming from Jerusalem, all of Judea, and the areas around the Jordan River to hear John the Baptist preach. This description is considered quite historically credible as it is backed up by Josephus. In his Antiquities of the Jews he says of John the Baptist that the others came in crowds about him, for they were very greatly moved by hearing his words . At the time Josephus was writing, around 97 AD, John the Baptist seems to have been an exceptionally more significant figure than Jesus - while John is frequently mentioned, hardly anyone appears to have mentioned Jesus at all, in all of Josephus' writing, there are only two very short passages which could possibly refer to Jesus, and these are heavily disputed with most scholars seeing them as forgeries.

Unlike Luke and Mark, Matthew has John being hesitant about baptising Jesus, with John stating that Jesus should be the one baptising him, though it doesn't exactly state why. The Gospel of the Nazoraeans, a text which has very strong similarities to Matthew, adds a clarification to this story, stating that it was because of Jesus' sinlessness that John felt he was the one who should be baptised. In the environment the author of Matthew is presumed to have been writing in there would still have been many followers of John the Baptist who felt he was equal to or superior to Jesus. And while the followers of John are often presented as becoming followers of Jesus, the ancient Mandaean religion, which survives much reduced to the present day, claims to originate in a direct line from the followers of John, without being tainted by following Jesus. This, and the fact that the available sources dating even c. 60 years after Jesus' recorded death paint John as the more significant figure, have led several people to propose that John's humility in the face of Jesus here is a fabrication by Matthew.

Baptism and John

In both Luke and Mark, John is described as baptising people to remove their sin. However, Matthew presents people merely as confessing their sins after they have been baptised. France argues that Matthew's theology differs from the other two synoptics by holding that unlike the other two, Matthew sees sin as only being possible to forgive once Jesus has been resurrected.

The origins of John's baptism ritual are much discussed amongst scholars. While various forms of baptism were practised throughout the Jewish world at this time, only those of John the Baptist and Qumran are associated with an eschatological purpose, leading many scholars to connect John to the group that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls. In Qumran, however, baptism was a regular ritual for individuals rather than the one-time event that the synoptics present it as. Obviously that the synoptics describe John as baptising people in the once-off form could simply be due to them putting a spin on John's historic behaviour due to being motivated to present him in accordance with Christian theology.

John the Baptist is described by Mark, Luke, and Matthew as referring to a successor, who will baptise with the Holy spirit and with fire. While John is presented as describing this successor as coming after him, it is important to note that the word usually translated after does not have a chronological meaning, but means instead after in sequence. It is often used to indicate that the one following is a disciple of the previous one (e.g., Matthew 4:19), but it also can simply mean behind (Matthew 16:23) or after (Luke 19:14, "after him"). At the time, the disciple of a Rabbi would be expected to perform menial chores, but as sandals were considered unclean, a view still persisting in the Middle East today, not even a disciple would deal with them, only the lowest slave. Thus when the text has John presenting himself as not worthy to carry/untie the sandals of his successor, he is presenting himself as extremely lowly in comparison.

Fire was often a symbol of wrath, and so linking the Holy Spirit with it superficially appears to clash with portrayals of this Spirit elsewhere in the New Testament as a gentle thing. Some translations avoid using the word fire due to this, but when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, it appeared that several of its texts make the connection between Holy Spirit and wrath, and so most scholars now see the wording here as original, and the other portrayals as misinterpreted. See also Acts 2.

It is worth noting that John baptising by water and his successor by fire has parallels with Sumerian mythology. Enki, who the Babylonians later knew as Ea, had become known as Oannes by the time of John, and Oannes is almost identical to Ioannes, which is how the name of John the Baptist is spelt in the original Greek of the New Testament. Enki/Oannes was the god of (pure) water, and although the first god, the god of creation, over time he lost significance, while the sun god grew more important. Hence in folklore of the period in the surrounding region, Oannes, god of water, was superseded by the god of the sun, the god of fire. That this folklore surrounding Oannes may have influenced a narrative built around a historic figure named Ioannes, is of course somewhat tenuous, though the connection is frequently made by those who question the Historicity of Jesus.

References

- Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- France, R.T. The Gospel According to Matthew: an Introduction and Commentary. Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1985.

- Gundry, Robert H. Matthew a Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1982.

- Guthrie, Donald. The New Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970.

- Hill, David. The Gospel of Matthew. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981

- Hurtago, Larry W. "Generation of Vipers." A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. David Lyle Jeffrey, general editor. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1992.

- Jones, Alexander. The Gospel According to St. Matthew. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1965.

- Malina, Bruce J. and Richard L. Rohrbaugh. Social-Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003.

- Murray, John. Christian Baptism. Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Pub., 1962.

- Schweizer, Eduard. The Good News According to Matthew. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975