| Revision as of 02:23, 7 January 2016 edit2605:e000:8789:d800:8430:dc33:b9a8:f58c (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:24, 7 January 2016 edit undo2605:e000:8789:d800:8430:dc33:b9a8:f58c (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 243: | Line 243: | ||

| {{Insecticides}} | {{Insecticides}} | ||

| {{Xenoestrogens}} | |||

| {{Androgenics}} | {{Androgenics}} | ||

| {{Estrogenics}} | {{Estrogenics}} | ||

Revision as of 02:24, 7 January 2016

| This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (February 2014) |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

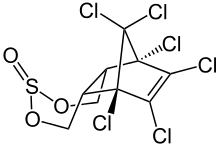

| IUPAC name 6,7,8,9,10,10-Hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro- 6,9-methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepine-3-oxide | |

| Other names Benzoepin, Endocel, Parrysulfan, Phaser, Thiodan, Thionex | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.709 |

| KEGG | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C9H6Cl6O3S |

| Molar mass | 406.90 g·mol |

| Appearance | Brown crystals |

| Odor | slight sulfur dioxide odor |

| Density | 1.745 g/cm |

| Melting point | 70 to 100 °C (158 to 212 °F; 343 to 373 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| Solubility in water | 0.33 mg/L |

| Vapor pressure | 0.00001 mmHg (25 °C) |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

| Main hazards | T, Xi, N |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

|

| Flash point | noncombustible |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

| PEL (Permissible) | none |

| REL (Recommended) | TWA 0.1 mg/m |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | N.D. |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Endosulfan is an off-patent organochlorine insecticide and acaricide that is being phased out globally. The two isomers, endo and exo, are known popularly as I and II. Endosulfan sulfate is a product of oxidation containing one extra O atom attached to the S atom. Endosulfan became a highly controversial agrichemical due to its acute toxicity, potential for bioaccumulation, and role as an endocrine disruptor. Because of its threats to human health and the environment, a global ban on the manufacture and use of endosulfan was negotiated under the Stockholm Convention in April 2011. The ban will take effect in mid-2012, with certain uses exempted for five additional years. More than 80 countries, including the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, several West African nations, the United States, Brazil, and Canada had already banned it or announced phase-outs by the time the Stockholm Convention ban was agreed upon. It is still used extensively in India, China, and few other countries. It is produced by Makhteshim Agan and several manufacturers in India and China.

Uses

Endosulfan has been used in agriculture around the world to control insect pests including whiteflies, aphids, leafhoppers, Colorado potato beetles and cabbage worms. Due to its unique mode of action, it is useful in resistance management; however, as it is not specific, it can negatively impact populations of beneficial insects. It is, however, considered to be moderately toxic to honey bees, and it is less toxic to bees than organophosphate insecticides.

Production

The World Health Organization estimated worldwide annual production to be about 9,000 metric tonnes (t) in the early 1980s. From 1980 to 1989, worldwide consumption averaged 10,500 tonnes per year, and for the 1990s use increased to 12,800 tonnes per year.

Endosulfan is a derivative of hexachlorocyclopentadiene, and is chemically similar to aldrin, chlordane, and heptachlor. Specifically, it is produced by the Diels-Alder reaction of hexachlorocyclopentadiene with cis-butene-1,4-diol and subsequent reaction of the adduct with thionyl chloride. Technical endosulfan is a 7:3 mixture of stereoisomers, designated α and β. α- and β-Endosulfan are configurational isomers arising from the pyramidal stereochemistry of the teravalent sulfur. α-Endosulfan is the more thermodynamically stable of the two, thus β-endosulfan irreversibly converts to the α form, although the conversion is slow.

History of commercialization and regulation

- Early 1950s: Endosulfan was developed.

- 1954: Hoechst AG (now Sanofi) won USDA approval for the use of endosulfan in the United States.

- 2000: Home and garden use in the United States was terminated by agreement with the EPA.

- 2002: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommended that endosulfan registration should be cancelled, and the EPA determined that endosulfan residues on food and in water pose unacceptable risks. The agency allowed endosulfan to stay on the US market, but imposed restrictions on its agricultural uses.

- 2007: International steps were taken to restrict the use and trade of endosulfan. It is recommended for inclusion in the Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent, and the European Union proposed inclusion in the list of chemicals banned under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Such inclusion would ban all use and manufacture of endosulfan globally. Meanwhile, the Canadian government announced that endosulfan was under consideration for phase-out, and Bayer CropScience voluntarily pulled its endosulfan products from the U.S. market but continues to sell the products elsewhere.

- 2008: In February, environmental, consumer, and farm labor groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council, Organic Consumers Association, and the United Farm Workers called on the U.S. EPA to ban endosulfan. In May, coalitions of scientists, environmental groups, and arctic tribes asked the EPA to cancel endosulfan, and in July a coalition of environmental and workers groups filed a lawsuit against the EPA challenging its 2002 decision to not ban it. In October, the Review Committee of the Stockholm Convention moved endosulfan along in the procedure for listing under the treaty, while India blocked its addition to the Rotterdam Convention.

- 2009: The Stockholm Convention's Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC) agreed that endosulfan is a persistent organic pollutant and that "global action is warranted", setting the stage of a global ban. New Zealand banned endosulfan.

- 2010: The POPRC nominated endosulfan to be added to the Stockholm Convention at the Conference of Parties (COP) in April 2011, which would result in a global ban. The EPA announced that the registration of endosulfan in the U.S. will be cancelled Australia banned the use of the chemical.

- 2011: The Supreme Court of India banned manufacture, sale, and use of toxic pesticide endosulfan in India. The apex court said the ban would remain effective for eight weeks during which an expert committee headed by DG, ICMR, will give an interim report to the court about the harmful effect of the widely used pesticide.

- 2011: the Argentinian Service for Sanity and Agroalimentary Quality (SENASA) decided on August 8 that the import of endosulfan into the South American country will be banned from July 1, 2012 and its commercialization and use from July 1, 2013. In the meantime, a reduced quantity can be imported and sold.

Health effects

Endosulfan is one of the most toxic pesticides on the market today, responsible for many fatal pesticide poisoning incidents around the world. Endosulfan is also a xenoestrogen—a synthetic substance that imitates or enhances the effect of estrogens—and it can act as an endocrine disruptor, causing reproductive and developmental damage in both animals and humans. It has also been found to act as an aromatase inhibitor. Whether endosulfan can cause cancer is debated. With regard to consumers' intake of endosulfan from residues on food, the Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations has concluded that long-term exposure from food is unlikely to present a public health concern, but short-term exposure can exceed acute reference doses.

Toxicity

Endosulfan is acutely neurotoxic to both insects and mammals, including humans. The US EPA classifies it as Category I: "Highly Acutely Toxic" based on a LD50 value of 30 mg/kg for female rats, while the World Health Organization classifies it as Class II "Moderately Hazardous" based on a rat LD50 of 80 mg/kg. It is a GABA-gated chloride channel antagonist, and a Ca, Mg ATPase inhibitor. Both of these enzymes are involved in the transfer of nerve impulses. Symptoms of acute poisoning include hyperactivity, tremors, convulsions, lack of coordination, staggering, difficulty breathing, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and in severe cases, unconsciousness. Doses as low as 35 mg/kg have been documented to cause death in humans, and many cases of sublethal poisoning have resulted in permanent brain damage. Farm workers with chronic endosulfan exposure are at risk of rashes and skin irritation.

EPA's acute reference dose for dietary exposure to endosulfan is 0.015 mg/kg for adults and 0.0015 mg/kg for children. For chronic dietary expsoure, the EPA references doses are 0.006 mg/(kg·day) and 0.0006 mg/(kg·day) for adults and children, respectively.

Endocrine disruption

Theo Colborn, an expert on endocrine disruption, lists endosulfan as a known endocrine disruptor, and both the EPA and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry consider endosulfan to be a potential endocrine disruptor. Numerous in vitro studies have documented its potential to disrupt hormones and animal studies have demonstrated its reproductive and developmental toxicity, especially among males. A number of studies have documented that it acts as an antiandrogen in animals. Endosulfan has shown to affect crustacean molt cycles, which are important biological and endocrine-controlled physiological processes essential for the crustacean growth and reproduction. Environmentally relevant doses of endosulfan equal to the EPA's safe dose of 0.006 mg/kg/day have been found to affect gene expression in female rats similarly to the effects of estrogen. It is not known whether endosulfan is a human teratogen (an agent that causes birth defects), though it has significant teratogenic effects in laboratory rats. A 2009 assessment concluded the endocrine disruption in rats occurs only at endosulfan doses that cause neurotoxicity.

Reproductive and developmental effects

Several studies have documented that endosulfan can also affect human development. Researchers studying children from many villages in Kasargod District, Kerala, India, have linked endosulfan exposure to delays in sexual maturity among boys. Endosulfan was the only pesticide applied to cashew plantations in the villages for 20 years, and had contaminated the village environment. The researchers compared the villagers to a control group of boys from a demographically similar village that lacked a history of endosulfan pollution. Relative to the control group, the exposed boys had high levels of endosulfan in their bodies, lower levels of testosterone, and delays in reaching sexual maturity. Birth defects of the male reproductive system, including cryptorchidism, were also more prevalent in the study group. The researchers concluded, "our study results suggest that endosulfan exposure in male children may delay sexual maturity and interfere with sex hormone synthesis." Increased incidences of cryptorchidism have been observed in other studies of endosulfan exposed populations.

A 2007 study by the California Department of Public Health found that women who lived near farm fields sprayed with endosulfan and the related organochloride pesticide dicofol during the first eight weeks of pregnancy are several times more likely to give birth to children with autism. This is the first study to look for an association between endosulfan and autism, and additional study is needed to confirm the connection. A 2009 assessment concluded that epidemiology and rodent studies that suggest male reproductive and autism effects are open to other interpretations, and that developmental or reproductive toxicity in rats occurs only at endosulfan doses that cause neurotoxicity.

Endosulfan and cancer

Endosulfan is not listed as known, probable, or possible carcinogen by the EPA, IARC, or other agencies. No epidemiological studies link exposure to endosulfan specifically to cancer in humans, but in vitro assays have shown that endosulfan can promote proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Evidence of carcinogenicity in animals is mixed.

Environmental fate

Endosulfan is a ubiquitous environmental contaminant. The chemical is semivolatile and persistent to degradation processes in the environment. Endosulfan is subject to long-range atmospheric transport, i.e. it can travel long distances from where it is used. Thus, it occurs in many environmental compartments. For example, a 2008 report by the National Park Service found that endosulfan commonly contaminates air, water, plants, and fish of national parks in the US. Most of these parks are far from areas where endosulfan is used. Endosulfan has been found in remote locations such as the Arctic Ocean, as well as in the Antarctic atmosphere. The pesticide has also been detected in dust from the Sahara Desert collected in the Caribbean after being blown across the Atlantic Ocean. The compound has been shown to be one of the most abundant organochlorine pesticides in the global atmosphere.

The compound breaks down into endosulfan sulfate, endosulfan diol, and endosulfan furan, all of which have structures similar to the parent compound and, according to the EPA, "are also of toxicological concern…The estimated half-lives for the combined toxic residues (endosulfan plus endosulfan sulfate) from roughly 9 months to 6 years." The EPA concluded, "ased on environmental fate laboratory studies, terrestrial field dissipation studies, available models, monitoring studies, and published literature, it can be concluded that endosulfan is a very persistent chemical which may stay in the environment for lengthy periods of time, particularly in acid media." The EPA also concluded, "ndosulfan has relatively high potential to bioaccumulate in fish." It is also toxic to amphibians; low levels have been found to kill tadpoles.

In 2009, the committee of scientific experts of the Stockholm Convention concluded, "endosulfan is likely, as a result of long range environmental transport, to lead to significant adverse human health and environmental effects such that global action is warranted." In May 2011, the Stockholm Convention committee approved the recommendation for elimination of production and use of endosulfan and its isomers worldwide. This is, however, subject to certain exemptions. Overall, this will lead to its elimination from the global markets.

Status by region

India

Although classified as a yellow label (highly toxic) pesticide by the Central Insecticides Board, India is one of the largest producers and the largest consumer of endosulfan in the world. Of the total volume manufactured in India, three companies — Excel Crop Care, Hindustan Insecticides Ltd, and Coromandal Fertilizers — produce 4,500 tonnes annually for domestic use and another 4,000 tonnes for export. Endosulfan is widely used in most of the plantation crops in India. The toxicity of endosulfan and health issues due to its bioaccumulation came under media attention when health issues precipitated in the Kasargod District (of Kerala) were publicised. This inspired protests, and the pesticide was banned in Kerala as early as 2001, following a report by the National Institute of Occupational Health. In the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants of 2011, when an international consensus arose for the global ban of the pesticide, India opposed this move due to pressure from the endosulfan manufacturing companies. This flared up the protest, and while India still maintained its stance, the global conference decided on a global ban, for which India asked a remission for 10 years. Later, on a petition filed in the Supreme Court of India, the production, storage, sale and use of the pesticide was temporarily banned on 13 May 2011, and later permanently by the end of 2011.

The Karnataka government also banned the use of endosulfan with immediate effect. Briefing presspersons after the State Cabinet meeting, Minister for Higher Education V.S. Acharya said the Cabinet discussed the harmful effects of endosulfan on the health of farmers and people living in rural areas. The government will now invoke the provisions of the Insecticides Act, 1968 (a Central act) and write a letter to the Union Government about the ban. Minister for Energy, and Food and Civil Supplies Shobha Karandlaje, who has been spearheading a movement seeking a ban on endosulfan, said, "I am grateful to Chief Minister B.S. Yeddyurappa and members of the Cabinet for approving the ban.

Rajendra Singh Rana has written a letter to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh demanding the withdrawal of the National Institute of Occupational Health (NIOH) study on Endosulfan titled "Report Of The Investigation Of Unusual Illness" allegedly produced by the Endosulfan exposure in Padre village of Kasargod district in north Kerala. In his statement Mr. Rana said "The NIOH report is flawed. I'm in complete agreement with what the workers have to say on this. In fact, I have already made representation to the Prime Minister and concerned Union Ministers of health and environment demanding immediate withdrawal of the report," as reported by The Economic Times and Outlook India

Mrs. Vibhavari Dave, local leader and Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA), from Bhavnagar, Gujarat, voiced her concerns on the impact of ban of endosulfan on families and workers of Bhavnagar. She was a part of the delegation with Bhavnagar MP, Rajendra Singh Rana, which submitted a memorandum to the district collector's office to withdraw the NIOH report calling for ban of endosulfan. The Pollution Control Board of the Government of Kerala, prohibited the use of endosulfan in the state of Kerala on 10 November 2010. On February 18, 2011, the Karnataka government followed suit and suspended the use of endosulfan for a period of 60 days in the state. Indian Union Minister of Agriculture Sharad Pawar has ruled out implementing a similar ban at the national level despite the fact that endosulfan has banned in 63 countries, including the European Union, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Government of Gujarat had initiated a study in response to the workers' rally in Bhavnagar and representations made by Sishuvihar, an NGO based in Ahmadabad. The committee constituted for the study also included former Deputy Director of NIOH, Ahmadabad. The committee noted that the WHO, FAO, IARC and US EPA have indicated that endosulfan is not carcinogenic, not teratogenic, not mutagenic and not genotoxic. The highlight of this report is the farmer exposure study based on analysis of their blood reports for residues of endosulfan and the absence of any residues. This corroborates the lack of residues in worker-exposure studies.

The Supreme Court passed interim order on May 13, 2011, in a Writ Petition filed by Democratic Youth Federation of India, (DYFI), a youth wing of Communist Party of India (Marxist) in the backdrop of the incidents reported in Kasargode, Kerala, and banned the production, distribution and use of endosulfan in India because the pesticide has debilitating effects on humans and the environment. The Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) welcomed this order, and called it a 'resounding defeat' for the pesticide industry which has been promoting this deadly toxin. A 2001 study by CSE had established the linkages between the aerial spraying of the pesticide and the growing health disorders in Kasaragode.Over the years, other studies have confirmed these findings, and the health hazards associated with endosulfan are now widely known and accepted. However, in July 2012, the Government asked the Supreme Court to allow use of the pesticide in all states except Kerala and Karnataka, as these states are ready to use it for pest control.

New Zealand

Endosulfan was banned in New Zealand by the Environmental Risk Management Authority effective January 2009 after a concerted campaign by environmental groups and the Green Party.

See also: Pesticides in New ZealandPhilippines

A shipment of about 10 tonnes of endosulfan was illegally stowed on the ill-fated MV Princess of the Stars, a ferry that sank off the waters of Romblon (Sibuyan Island), Philippines, during a storm in June 2008. Search, rescue, and salvage efforts were suspended when the endosulfan shipment was discovered, and blood samples from divers at the scene were sent to Malaysia for analysis. The Department of Health of the Philippines has temporarily banned the consumption of fish caught in the area. Endosulfan is classified as a "Severe Marine Pollutant" by the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code.

United States

In the United States, endosulfan is only registered for agricultural use, and these uses are being phased out. It has been used extensively on cotton, potatoes, tomatoes, and apples according to the EPA. The EPA estimates that 626 thousand kg of endosulfan were used annually from 1987 to 1997. The US exported more than 140,000 lb of endosulfan from 2001 to 2003, mostly to Latin America, but production and export has since stopped.

In California, endosulfan contamination from the San Joaquin Valley has been implicated in the extirpation of the mountain yellow-legged frog from parts of the nearby Sierra Nevada. In Florida, levels of contamination the Everglades and Biscayne Bay are high enough to pose a threat to some aquatic organisms.

In 2007, the EPA announced it was rereviewing the safety of endosulfan. The following year, Pesticide Action Network and NRDC petitioned the EPA to ban endosulfan, and a coalition of environmental and labor groups sued the EPA seeking to overturn its 2002 decision to not ban endosulfan. In June 2010, the EPA announced it was negotiating a phaseout of all uses with the sole US manufacturer, Makhteshim Agan, and a complete ban on the compound.

An official statement by Makhteshim Agan of North America (MANA) states, "From a scientific standpoint, MANA continues to disagree fundamentally with EPA's conclusions regarding endosulfan and believes that key uses are still eligible for re-registration." The statement adds, "However, given the fact that the endosulfan market is quite small and the cost of developing and submitting additional data high, we have decided to voluntarily negotiate an agreement with EPA that provides growers with an adequate time frame to find alternatives for the damaging insect pests currently controlled by endosulfan."

Australia

Australia banned endosulfan on October 12, 2010, with a two-year phase-out for stock of endosulfan-containing products. Australia had, in 2008, announced endosulfan would not be banned. Citing New Zealand's ban, the Australian Greens called for "zero tolerance" of endosulfan residue on food.

Taiwan

US apples with endosulfan are now allowed to be exported to Taiwan, although the ROC government denied any US pressure on it.

Brazil

Brazil decreed total ban of the substance from July 31, 2013, being forbidden imports of the product from July 31, 2011, date in which national production and utilization begins to be phased out gradually.

References

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0251". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Bayer to stop selling endosulfan". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. July 17, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/article1968299.ece

- "Endosulfan: Supreme Court to hear seeking ban on Monday". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Australia should ban endosulfan: Greens". Weekly Times. News Limited. January 8, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- Cone, Marla. EPA Bans Pesticide Found on Cucumbers, Zucchini, Green Beans and Other Vegetables. The Daily Green. June 10, 2010.

- ^ "EPA Action to Terminate Endosulfan". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- http://www.agrow.com/markets/southamerica/Endosulfan-ban-in-Brazil-from-2013-299753?autnRef=/contentstore/agrow/codex/0bef898a-90fc-11df-870a-bbcce1c03e31.xml

- PMRA: Re-evaluation Note REV2011-01, Discontinuation of Endosulfan http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/cps-spc/pubs/pest/_decisions/rev2011-01/index-eng.php

- ^ Government of Canada (January 10, 2009). "Endosulfan: Canada's submission of information specified in Annex E of". Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Mossler, Mark; Michael J. Aerts; O. Norman Nesheim (March 2006). "Florida Crop/Pest Management Profiles: Tomatoes. CIR 1238" (PDF). University of Florida, IFAS Extension. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- Extension Toxicology Network (June 1996). "Pesticide Information Profile: Endosulfan". Oregon State University.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ US EPA, Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Endosulfan, November 2002.

- World Health Organization, Environmental Health Criteria 40, 1984.

- (a) Schmidt WF, Hapeman CJ, Fettinger JC, Rice CP, and Bilboulian S, J. Ag. Food Chem., 1997, 45(4): 1023–1026.

(b) Schmidt WF, Bilboulian S, Rice CP, Fettinger JC, McConnell LL, and Hapeman CJ, J. Ag. Food Chem., 2001, 49(11): 5372–5376. - Robert L. Metcalf "Insect Control" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry" Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_263

- ^ Agency of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Toxicological Profile for Endosulfan, 2000.

- Kay, Jane (March 2, 2006). "A move to ease pesticide laws". San Francisco Chronicle. pp. A1..

- ^ Secretariat for the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (16 October 2007). "Draft Decision Guidance Document" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ^ "SUMMARY OF THE FOURTH MEETING OF THE PERSISTENT ORGANIC POLLUTANTS REVIEW COMMITTEE OF THE STOCKHOLM CONVENTION". Earth Negotiations Bulletin. 15 (161). October 20, 2008.

- Canada to end endosulfan use? Agrow, Oct 22, 2007.

- Note to Reader. Endosulfan: Request for Additional Information on Usage and Availability of Alternatives, U.S. EPA, Nov. 16, 2007.

- Our Products: Endosulfan, BayerCropScience.com, Accessed 03/03/08.

- PETITION TO BAN ENDOSULFAN AND REVOKE ALL TOLERANCES AND COMMENTS ON THE ENDOSULFAN UPDATED RISK ASSESSMENT (OPP-2002-0262-0067) BY THE NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL, National Resources Defense Council, Feb. 2008.

- Thousands Tell EPA: Phase Out Endosulfan, Pesticide Action Network, Feb. 18, 2008

- Sass J, Janssen S; Janssen (2008). "Open letter to Stephen Johnson, Administrator, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: ban endosulfan". Int J Occup Environ Health. 14 (3): 236–9. doi:10.1179/oeh.2008.14.3.236. PMID 18686727.

- Erickson, Britt (May 21, 2008). "Groups Petition EPA To Ban Endosulfan". Chemical and Engineering News.

- ^ "Group sues to ban DDT-related pesticide". The Mercury News. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - POPRC-4 — Summary and Analysis, 20 October 2008, The International Institute for Sustainable Development – Reporting Services Division.

- Dutta, Mahdumita (November 21, 2008). "To Industry's Tune". Down to Earth. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention (16 October 2009). "Endosulfan and other chemicals being assessed for listing under the Stockholm Convention". Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "ERMA: Endosulfan Use Prohibited". ENVIRONMENTAL RISK MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY. December 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- "UN chemical body recommends elimination of the toxic pesticide endosulfan". Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- Martin, David S. EPA moves to ban DDT cousin. CNN. June 10, 2010.

- "Australia finally bans endosulfan. 13 Oct 2010. National Rural News. (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- "SC bans sale and use of toxic pesticide endosulfan. 13 May 2011. The Times of India". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. May 13, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-29.

- "Endosulfan: nuevas medidas para la importación, elaboración y uso en Argentina. 8 Aug 2011 SENASA". www.senasa.gov.ar. Retrieved 2011-08-29.

- Pesticide Action Network North America, Speaking the Truth Saves Lives in the Philippines and India, PAN Magazine, Fall 2006.

- ^ Raun Andersen, Helle; Vinggaard, Anne Marie; Høj Rasmussen, Thomas; Gjermandsen, Irene Marianne; Cecilie Bonefeld-Jørgensen, Eva (2002). "Effects of Currently Used Pesticides in Assays for Estrogenicity, Androgenicity, and Aromatase Activity in Vitro". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 179 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/taap.2001.9347. ISSN 0041-008X.

- "Pesticide residues in food 2006 - Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2006.

- World Health Organization, The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard, 2005.

- International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization, Endosulfan (Poison Information Monograph 576), July 2000.

- Colborn T, Dumanoski D, Meyers JP, Our Stolen Future : How We Are Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival, 1997, Plume.

- Wilson VS, LeBlanc GA; Leblanc (January 1998). "Endosulfan elevates testosterone biotransformation and clearance in CD-1 mice". Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 148 (1): 158–68. doi:10.1006/taap.1997.8319. PMID 9465275.

- Tumburu L, Shepard EF, Strand AE, Browdy CL; Shepard; Strand; Browdy (November 2011). "Effects of endosulfan exposure and Taura Syndrome Virus infection on the survival and molting of the marine penaeid shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei". Chemosphere. 86 (9): 912–8. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.10.057. PMID 22119282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Varayoud J, Monje L, Bernhardt T, Muñoz-de-Toro M, Luque EH, Ramos JG; Monje; Bernhardt; Muñoz-De-Toro; Luque; Ramos (October 2008). "Endosulfan modulates estrogen-dependent genes like a non-uterotrophic dose of 17beta-estradiol". Reprod. Toxicol. 26 (2): 138–45. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.08.004. PMID 18790044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Singh ND, Sharma AK, Dwivedi P, Patil RD, Kumar M; Sharma; Dwivedi; Patil; Kumar (2007). "Citrinin and endosulfan induced teratogenic effects in Wistar rats". J Appl Toxicol. 27 (2): 143–51. doi:10.1002/jat.1185. PMID 17186572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silva MH, Gammon D; Gammon (February 2009). "An assessment of the developmental, reproductive, and neurotoxicity of endosulfan". Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 86 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20183. PMID 19243027.

- Saiyed H, Dewan A, Bhatnagar V, et al., Effect of Endosulfan on Male Reproductive Development, Environ. Health Perspect., 2003, 111:1958–1962.

- (a) Damgaard IN, Skakkebæk NE, Toppari J, et al., Persistent Pesticides in Human Breast Milk and Cryptorchidism, Environ. Health Perspect., 2006, 114:1133–1138.

(b) Olea N, Olea-Serrano F, Lardelli-Claret P, et al., Inadvertent Exposure to Xenoestrogens in Children, Toxicol. Ind. Health, 15:151–158. - (a) Roberts EM, English PB, Grether JK, Windham GC, Somberg L, Wolff C; English; Grether; Windham; Somberg; Wolff (2007). "Maternal Residence Near Agricultural Pesticide Applications and Autism Spectrum Disorders among Children in the California Central Valley". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (10): 1482–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.10168. PMC 2022638. PMID 17938740.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

(b) Lay Summary: Autism and Agricultural Pesticides, Victoria McGovern, Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115(10):A505 - (a) Grunfeld HT, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC, Effect of in vitro estrogenic pesticides on human oestrogen receptor alpha and beta mRNA levels, Toxicol. Lett., 2004, 151(3):467–80.

(b) Ibarluzea JmJ, Fernandez MF, Santa-Marina L, et al., Breast cancer risk and the combined effect of environmental estrogens, Cancer Causes Control, 2004, 15(6):591–600.

(c) Soto AM, Chung KL, Sonnenschein C, The pesticides endosulfan, toxaphene, and dieldrin have estrogenic effects on human estrogensensitive cells, Environ. Health Perspect., 1994, 102(4):380–383. - Western Airborne Contaminants Assessment Project, National Park Service.

- ^ Endosulfan, a global pesticide: A review of its fate in the environment and occurrence in the Arctic, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 408, Issue 15.

- Ramnarine, Kristy (May 12, 2008). "Harmful elements in Sahara dust". Trinidad & Tobago Express. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Relyea RA (2008) A cocktail of contaminants: how mixtures of pesticides at low concentrations affect aquatic communities. Oecologia (accepted: 13 October 2008) Relyea, Ra (Mar 2009). "A cocktail of contaminants: how mixtures of pesticides at low concentrations affect aquatic communities". Oecologia. 159 (2): 363–76. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1213-9. PMID 19002502.

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin (19 October 2009). "Briefing Note on the 5th Meeting of the POPRC" (PDF). International Institute for Sustainable Development.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (Press release). UNEP. May 3, 2011 http://hqweb.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=2637&ArticleID=8719&l=en&t=long. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

{{cite press release}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Indian Chemical Council (January 9, 2009). "Form for submission of information specified in Annex E". Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Uppinangady, Arun (July 14, 2009). "Beltangady: Endosulfan Affected Leading Hellish Life — Seek Succour". Daijiworld Media Network. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- 'Rain man' of Indian journalism makes sure wells stay full, Frederick Noronha, IndiaENews.com, July 5th, 2007, accessed July 5th, 2007.

- "SUMMARY OF THE FOURTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO THE ROTTERDAM CONVENTION". Earth Negotiations Bulletin. 15 (168). November 3, 2008.

- http://www.indiatogether.org/2006/sep/env-endosulf.htm

- "V.S. Achuthanandan to lead 'satyagraha'". The Hindu. Chennai, India. April 24, 2011.

- http://www.indianexpress.com/news/MP-govt-backs-VS-ban-demand/783265/

- "Karnataka bans use of endosulfan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. February 18, 2011.

- "Rana Wants Withdrawal of NIOH Study on Endosulfan". Outlook India. November 16, 2010.

- "Rajendra Singh Rana, MP, Bhavnagar calls for withdrawal of NIOH report on Endosulfan". World News. December 17, 2010.

- "Local MLA speaks in support of Bhavnagar Endosulfan Workers". Daily Motion. December 18, 2010.

- "Workers demand withdrawal of study on Endosulfan". WebIndia 123. November 16, 2010.

- , accessed Nov 19th, 2010

- "Karnataka bans use of endosulfan". Chennai, India: The Hindu. February 18, 2011.

- "India will not ban Endosulfan pesticide, says Sharad Pawar". Tehelka. February 22, 2011.

- "REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE TO EVALUATE THE SAFETY ASPECTS OF ENDOSULFAN Department" (PDF). Health and Family Welfare Department - Government of Gujarat. March 15, 2011.

- "REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE TO EVALUATE THE SAFETY ASPECTS OF ENDOSULFAN" (PDF). Department of Health and Family Welfare - Government of Gujarat. March 15, 2011. Retrieved March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Venkatesan, J. (27 July 2012). "Allow use of endosulfan except in Kerala and Karnataka". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- "Divers' blood samples sent to Singapore for analysis". GMAnews.TV. June 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Aguilar, Ephraim (June 27, 2008). "DoH bans eating of fish from Romblon waters". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Benefits of Endosulfan in Agricultural Production: Analysis of Usage Information, U.S. EPA, Docket ID NO. EPA-HQ-OPP-2002-0262-0062, 2007.

- Smith, Carl; Kathleen Kerr and Ava Sadripour (July–September 2008). "Pesticide Exports from US Ports, 2001–2003". Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 14 (3): 176–186. PMID 18686717.

- Fellers GM, McConnell LL, Pratt D, Datta S; McConnell; Pratt; Datta (September 2004). "Pesticides in mountain yellow-legged frogs (Rana muscosa) from the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, USA". Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 23 (9): 2170–7. doi:10.1897/03-491. PMID 15378994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carriger JF, Rand GM; Rand (October 2008). "Aquatic risk assessment of pesticides in surface waters in and adjacent to the Everglades and Biscayne National Parks: I. Hazard assessment and problem formulation". Ecotoxicology. 17 (7): 660–79. doi:10.1007/s10646-008-0230-0. PMID 18642080.

- Carriger JF, Rand GM; Rand (October 2008). "Aquatic risk assessment of pesticides in surface waters in and adjacent to the Everglades and Biscayne National Parks: II. Probabilistic analyses". Ecotoxicology. 17 (7): 680–96. doi:10.1007/s10646-008-0231-z. PMID 18642079.

- Dan B. Kimball, Superintendent National Park Service (October 29, 2008). "Letter to EPA re: Petitions to Revoke All Tolerances Established for Endosulfan; Federal Register: August 20, 2008 (Volume 73, Number 162). Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0615-0041.1". Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (November 16, 2007). "Endosulfan Updated Risk Assessments, Notice of Availability, and Solicitation of Usage Information". Federal Register. 72 (221): 64624–64626.

- ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (August 20, 2008). "Petitions to Revoke All Tolerances Established for Endosulfan; Notice of Availability". 73 (162): 49194–49196.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "MANA And EPA Agree To Voluntary Plan On Endosulfan". MANA Crop Protection. June 10, 2010.

- "MANA, EPA Agree To Voluntary Plan On Endosulfan". Growing Produce. June 11, 2010.

- ^ Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) apvma (Press release). Commonwealth of Australia. October 12, 2010 http://www.apvma.gov.au/news_media/media_releases/2010/mr2010-12.php. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

{{cite press release}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); line feed character in|work=at position 65 (help) - "Australia finally bans endosulfan". Australia: ABC. 13 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- "Regulator finally acts to ban endosulfan". NTN blog. Australia: National Toxics Network. October 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Burke, Kelly (January 7, 2009). "Australia refuses to join ban on pesticide". Fairfax. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- Taiwan Academics slam end of pesticide ban for U.S. fruit

- Formenti, Lígia (July 15, 2010). "Agrotóxico endosulfan será banido no Brasil em 2013; demora é criticada". Estadão. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

External links

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- 2009 Environmental Justice Foundation report detailing impacts of Endosulfan, highlighting why it should be banned globally

- Resources on Endosulfan, India Environment Portal

- Pesticideinfo.org: Endosulfan

- Levels of endosulfan residues on food in the U.S.

- Endosulphan Victims in Kerala

- Protect Endosufan Network — Information about endosulfan from Protect Endosufan Network.

- State of endosulfan, Down To Earth

- Interim report on endosulfan submitted by expert committee to the Supreme Court of India, Aug 4, 2011

- Weeping wombs of Kasaragod Tehelka Magazine, Vol 8, Issue 18, Dated 07 May 2011

| Androgen receptor modulators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTooltip Androgen receptor |

| ||||||

| GPRC6A |

| ||||||

| Estrogen receptor modulators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERTooltip Estrogen receptor |

| ||||||

| GPERTooltip G protein-coupled estrogen receptor |

| ||||||