| Revision as of 12:50, 28 May 2016 editDan Koehl (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers40,931 edits clean up, typo(s) fixed: beated → beat, eachother → each other using AWB← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:14, 4 July 2016 edit undoSorabino (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users25,397 editsm →Nemanjić dynastyNext edit → | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| {{main|Kingdom of Serbia (medieval)}} ] in 1265]] | {{main|Kingdom of Serbia (medieval)}} ] in 1265]] | ||

| Stefan Nemanja was succeeded by his middle son Stefan, while his first-born son Vukan was given the rule of the Zeta region (present-day Montenegro). Stefan Nemanja's youngest son Rastko became a monk (as ]), turning all his efforts to spread religion among his people. Since the Catholic Church already had ambitions to spread its influence to the Balkans as well, Stefan took advantage and obtained the royal crown from the Pope in 1217. In Byzantium, Sava managed to secure ] (independence) for the ] and became the first Serbian ] in 1219. In the same year Sava issued the first ] in ], the '']''. Thus the medieval Serbian state acquired both forms of independence: political and religious. | Stefan Nemanja was succeeded by his middle son Stefan, while his first-born son Vukan was given the rule of the Zeta region (present-day Montenegro). Stefan Nemanja's youngest son Rastko became a monk (as ]), turning all his efforts to spread religion among his people. Since the Catholic Church already had ambitions to spread its influence to the Balkans as well, Stefan took advantage and obtained the royal crown from the Pope in 1217. In Byzantium, Sava managed to secure ] (independence) for the ] and became the first Serbian ] in 1219. In the same year Sava issued the first ] in ], the '']''. Thus the medieval Serbian state acquired both forms of independence: political and religious. | ||

| The following seats were newly created in the time of Saint Sava: | |||

| * Žiča, the seat of the Archbishop at ]; | |||

| * ] (''Zetska''), seated at Monastery of Holy Archangel Michael in ] near ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Humska''), seated at ] in ], in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Dabarska''), seated at ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Moravička''), seated at ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Budimljanska''), seated at ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Toplička''), seated at ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Hvostanska''), seated at ] in ] region (northern ]). | |||

| Older eparchies under the jurisdiction of Serbian Archbishop were: | |||

| * ] (''Raška''), seated at ] near ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Lipljanska''), seated at ] in ] region; | |||

| * ] (''Prizrenska''), seated at ] in the south of ] region. | |||

| The next generation of Serbian rulers, the sons of King Stefan, ], ] and ], marked a period of stagnation of the state structure. All three kings were more or less dependent on some of the neighbouring states—], ] or Hungary. The ties with the Hungarians played a decisive role in the fact that Uroš I was succeeded by his son ], whose wife was a Hungarian princess. Later on, when Dragutin abdicated in favor of his younger brother ] (in 1282), the Hungarian king ] gave him lands in northeastern ], the region of ], and the city of ], while he managed to conquer and annex lands in northeastern ]. Thus, some of these territories became part of the Serbian state for the first time. His new state was named ''Kingdom of Srem''. In that time the name ''Srem'' was a designation for two territories: ''Upper Srem'' (present day ]) and ''Lower Srem'' (present day Mačva). Kingdom of Srem under the rule of Stefan Dragutin was actually Lower Srem, but some historical sources mention that Stefan Dragutin also ruled over Upper Srem and ]. After Dragutin died (in 1316), the new ruler of the ''Kingdom of Srem'' became his son, king ], who ruled this state until 1325. | The next generation of Serbian rulers, the sons of King Stefan, ], ] and ], marked a period of stagnation of the state structure. All three kings were more or less dependent on some of the neighbouring states—], ] or Hungary. The ties with the Hungarians played a decisive role in the fact that Uroš I was succeeded by his son ], whose wife was a Hungarian princess. Later on, when Dragutin abdicated in favor of his younger brother ] (in 1282), the Hungarian king ] gave him lands in northeastern ], the region of ], and the city of ], while he managed to conquer and annex lands in northeastern ]. Thus, some of these territories became part of the Serbian state for the first time. His new state was named ''Kingdom of Srem''. In that time the name ''Srem'' was a designation for two territories: ''Upper Srem'' (present day ]) and ''Lower Srem'' (present day Mačva). Kingdom of Srem under the rule of Stefan Dragutin was actually Lower Srem, but some historical sources mention that Stefan Dragutin also ruled over Upper Srem and ]. After Dragutin died (in 1316), the new ruler of the ''Kingdom of Srem'' became his son, king ], who ruled this state until 1325. | ||

Revision as of 01:14, 4 July 2016

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Serbian. (December 2014) Click for important translation instructions.

|

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Тhe medieval history of Serbia begins in the 6th century with the Slavic invasion of the Balkans, and lasts until the Ottoman occupation of 1540.

Early Middle Ages

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Serbian. (December 2014) Click for important translation instructions.

|

Slavic settlement

Main article: Slavic invasion of the BalkansSclaveni raided and settled the western Balkans in the 6th and 7th century. The Serbs are mentioned in De Administrando Imperio as having settled the Balkans during the reign of Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641), however, research does not support that the Serbian tribe was part of this later migration (as held by historiography) rather than migrating with the rest of Early Slavs. Through linguistical studies, it is concluded that the Early South Slavs were made up of a western and eastern branch, of parallel streams, roughly divided in the Timok–Osogovo–Šar line. Archaeological evidence in Serbia and Macedonia shows that the White Serbs may have reached the Balkans earlier than thought, between 550–600, as many findings of fibulae and pottery at Roman forts point to Serbian characteristics and thus could have represent traces of either part of the Byzantine foedorati or a fraction of the early invading Slavs who upon organizing in their refuge of the Dinarides, formed the ethnogenesis of Serbs and were pardoned by the Byzantine Empire after acknowledging their suzerainty.

De Administrando Imperio on the Serbs

The history of the early medieval Serbian Principality and the Vlastimirović dynasty (ruled ca. 610–960) is recorded in the work De Administrando Imperio ("On the Governance of the Empire", DAI), compiled by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (r. 913–959). The DAI drew information on the Serbs from, among others, a Serbian source. The work mentions the first Serbian ruler, without a name (known conventionally as the "Unknown Archon"), that led the Serbs from the north to the Balkans and received the protection of Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641), and was said to have died long before the Bulgar invasion (680).

First Serbian principality

Main article: Principality of Serbia (medieval)According to DAI, "baptized Serbia" (known erranously in historiography as Raška), included the inhabited cities (καστρα/kastra) of Destinikon (Δεστινίκον), Tzernabouskeï (Τζερναβουσκέη), Megyretous (Μεγυρέτους), Dresneïk (Δρεσνεήκ), Lesnik (Λεσνήκ), Salines (Σαληνές), while the "small land" (χοριον/chorion) of Bosna (Βοσωνα), part of Serbia, had the cities of Katera (Κατερα) and Desnik (Δέσνηκ). The first capital was Ras, in Raška (southwestern Serbia). The other Serb-inhabited lands (or principalities) that were mentioned included the "countries" of Paganija, Zahumlje and Travunija, while the "land" of Duklja was held by the Byzantines (it was presumably settled with Serbs as well). These polities bordered Serbia to the north. The exact borders of the early Serbian state are unclear. The Serbian ruler was titled "Prince (archon) of the Serbs" (αρχων Σερβλίας). The DAI mentions that the Serbian throne is inherited by the son, i.e. the first-born; his descendants succeeded him, though their names are unknown until the coming of Višeslav.

High Middle Ages

Vojislavljević dynasty (Duklja)

Main article: DukljaDuklja was a medieval Serb state which roughly encompassed the territories of present-day southeastern Montenegro, from the Bay of Kotor in the west to the Bojana river in the east, and to the sources of the Zeta and Morača rivers in the north. First mentioned in 10th– and 11th century Byzantine chronicles, it was a vassal of the Byzantine Empire until it became independent in 1040 under Stefan Vojislav (fl. 1034–43) who rose up and managed to take over territories of the earlier Serbian principality, founding the Vojislavljević dynasty. Between 1043 and 1080, under Mihailo Vojislavljević (r. 1050–81), and his son, Constantine Bodin (r. 1081–1101), Duklja saw its apogee. Mihailo was given the nominal title King of Slavs by the Pope after having left the Byzantine camp and supported a Slavic uprising in the Balkans, in which his son Bodin played a central part. Having incorporated the Serbian hinterland and installed vassal rulers there, this maritime principality emerged as the most powerful Serb polity, seen in the titles used by its rulers ("Prince of Serbia", "of Serbs"). However, its rise was short-lived, as Bodin was defeated by the Byzantines and imprisoned; pushed to the background, his relative and vassal Vukan became independent in Raška, which continued the fight against the Byzantines while Duklja was struck with civil wars. Between 1113 and 1149 Duklja was the centre of Serbian–Byzantine conflict, with members of the Vojislavljević as protégés of either fighting each other for power. Duklja was then incorporated as a crown land of the Grand Principality of Serbia ruled by the Vukanović dynasty, subsequently known as Zeta, remaining so until the fall of the Serbian Empire in the 14th century.

Vukanović dynasty (Raška)

Main article: Grand Principality of SerbiaThe Serbian Grand Principality, also known as Rascia, was founded in 1090, and ended with the elevation to Kingdom in 1217. During the reign of Constantine Bodin, the King of Duklja, Vukan was appointed to rule Rascia as a vassal, and when Bodin was captured by the Byzantines, Vukan became independent and took the title of Grand Prince. When Bodin had died, Rascia became the strongest entity, in which the Serbian realm would be seated, in hands of the Vukanović dynasty. Uroš I, the son of Vukan, ruled Serbia when the Byzantines invaded Duklja, and Rascia would be next in line, but with diplomatic ties with the Kingdom of Hungary, Serbia retained its independence. Uroš II initially fought the Byzantines, but after a defeat soon gives oaths of servitude to the Emperor. Desa, the brother of Uroš II and an initial Byzantine ally, turned to Hungarian support, but was deposed in 1163, when Stefan Tihomir of a cadet line (which would become Nemanjić dynasty), was put on the throne by the Emperor.

Nemanjić dynasty

Main article: Kingdom of Serbia (medieval)

Stefan Nemanja was succeeded by his middle son Stefan, while his first-born son Vukan was given the rule of the Zeta region (present-day Montenegro). Stefan Nemanja's youngest son Rastko became a monk (as Sava), turning all his efforts to spread religion among his people. Since the Catholic Church already had ambitions to spread its influence to the Balkans as well, Stefan took advantage and obtained the royal crown from the Pope in 1217. In Byzantium, Sava managed to secure autocephaly (independence) for the Serbian Church and became the first Serbian archbishop in 1219. In the same year Sava issued the first constitution in Serbia, the Zakonopravilo. Thus the medieval Serbian state acquired both forms of independence: political and religious.

The following seats were newly created in the time of Saint Sava:

- Žiča, the seat of the Archbishop at Monastery of Žiča;

- Eparchy of Zeta (Zetska), seated at Monastery of Holy Archangel Michael in Prevlaka near Kotor in Zeta region;

- Eparchy of Hum (Humska), seated at Monastery of the Holy Mother of God in Ston, in Hum region;

- Eparchy of Dabar (Dabarska), seated at Monastery of St. Nicholas in Dabar region;

- Eparchy of Moravica (Moravička), seated at Monastery of St. Achillius in Moravica region;

- Eparchy of Budimlja (Budimljanska), seated at Monastery of St. George in Budimlja region;

- Eparchy of Toplica (Toplička), seated at Monastery of St. Nicholas in Toplica region;

- Eparchy of Hvosno (Hvostanska), seated at Monastery of the Holy Mother of God in Hvosno region (northern Metohija).

Older eparchies under the jurisdiction of Serbian Archbishop were:

- Eparchy of Ras (Raška), seated at Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul near Ras in Raška region;

- Eparchy of Lipljan (Lipljanska), seated at Lipljan in Kosovo region;

- Eparchy of Prizren (Prizrenska), seated at Prizren in the south of Metohija region.

The next generation of Serbian rulers, the sons of King Stefan, Stefan Radoslav, Stefan Vladislav and Stefan Uroš I, marked a period of stagnation of the state structure. All three kings were more or less dependent on some of the neighbouring states—Byzantium, Bulgaria or Hungary. The ties with the Hungarians played a decisive role in the fact that Uroš I was succeeded by his son Stefan Dragutin, whose wife was a Hungarian princess. Later on, when Dragutin abdicated in favor of his younger brother Milutin (in 1282), the Hungarian king Ladislaus IV gave him lands in northeastern Bosnia, the region of Mačva, and the city of Belgrade, while he managed to conquer and annex lands in northeastern Serbia. Thus, some of these territories became part of the Serbian state for the first time. His new state was named Kingdom of Srem. In that time the name Srem was a designation for two territories: Upper Srem (present day Srem) and Lower Srem (present day Mačva). Kingdom of Srem under the rule of Stefan Dragutin was actually Lower Srem, but some historical sources mention that Stefan Dragutin also ruled over Upper Srem and Slavonia. After Dragutin died (in 1316), the new ruler of the Kingdom of Srem became his son, king Vladislav II, who ruled this state until 1325.

Under the rule of Dragutin's younger brother—King Milutin, Serbia grew stronger despite having to occasionally fight wars on three different fronts. King Milutin was an apt diplomat much inclined to the use of a customary medieval diplomatic and dynastic marriages. He was married five times, with Hungarian, Bulgarian and Byzantine princesses. He is also famous for building churches, some of which are the finest examples of Medieval Serbian architecture: the Gračanica monastery in Kosovo, the Cathedral in Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos, the St. Archangel Church in Jerusalem etc. Because of his endowments, King Milutin has been proclaimed a saint, in spite of his tumultuous life.

Late Middle Ages

Nemanjić dynasty

Main articles: Kingdom of Serbia (medieval) and Serbian Empire

In the first half of the 14th century Serbia flourished, becoming one of the most developed countries and cultures in Europe. It had a high political, economic, and cultural reputation in Europe.

Milutin was succeeded by his son Stefan Dečanski, who maintained his father's kingdom and had monasteries built, the most notable being Visoki Dečani in Metohija (Kosovo), after which he is known in historiography. Visoki Dečani, Our Lady of Ljeviš and the Gračanica monastery, all founded by Dečanski, are part of the Medieval Monuments in Kosovo, a combined World Heritage Site. After decisively defeated the Bulgarians, Serbia was caught up in a civil war between two groups of the Serbian nobility, one supporting Dečanski, the other supporting his son Stefan Dušan which sought to expand to the south. Dušan won, and in the following decades fought the Byzantine Empire, taking advantage of the Byzantine civil wars. After conquering Albania, Macedonia and much of Greece, he was crowned Emperor in 1346, after having elevated the Serbian archbishopric into a patriarchate. He had his son crowned King, giving him nominal rule over the "Serbian lands", and although Dušan was governing the whole state, he had special responsibility for the "Roman" (Byzantine) lands. "Dušan's Code" was enacted in 1349 and 1353–54. Dušan sought to conquer Constantinople and become the new Byzantine emperor, however, he suddenly died in 1355 at the age of 47. The Serbian state crumbled during the reign of his son, Uroš V, called "the Weak", in a period known as the "Fall of the Serbian Empire".

Decline and Ottoman conquest

Main articles: Fall of the Serbian Empire, Moravian Serbia, and Serbian Despotate

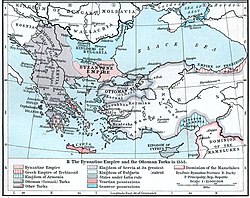

Following the death of child-less Emperor Uroš the Weak in 1371 (and end of the Nemanjić dynasty), the Empire was left without an heir and the magnates, velikaši, obtained the rule of its provinces and districts (in so called feudal fragmentation), continuing their offices as independent with titles such as gospodin, and despot, given to them during the Empire. The period saw the rise of a new threat, the Ottomans, Turkic warriors who overran Anatolia and subsequently the Balkans.

The Serbian Empire was divided between the feudal lords; without an Emperor, it became "a conglomerate of aristocratic territories", and the Empire was thus divided between the provincial lords: Marko Mrnjavčević, the Dejanović brothers, Đurađ I Balšić, Vuk Branković, Nikola Altomanović, and Lazar Hrebeljanović. Lazar managed to rule most of what is today Central Serbia (known as Moravian Serbia). He was unable to unite the Serbian magnates, as they were too powerful and pursued their own interests, fighting each other. Ottomans began raiding Serbia in 1381, though the actual invasion came later. In 1386, Lazar's knights beat the Ottoman army near Pločnik, in what is today southern Serbia. Another invasion by Ottomans came in the summer of 1389, this time aiming towards Kosovo.

On 28 June 1389 the two armies met at Kosovo, in a battle that ended in a draw, decimating both armies (both Lazar and Murad I fell). The battle is particularly important to Serbian history, tradition, and national identity (see Kosovo Myth). By now, the Balkans was unable to halt the advancing Ottomans. Eventually, Serbian nobility became Ottoman vassals.

Serbia managed to recuperate under Despot Stefan Lazarević, surviving for 70 more years, experiencing a cultural and political renaissance, but after Stefan Lazarević's death, his successors from the Branković dynasty did not manage to stop the Ottoman advance. Serbia finally fell under the Ottomans in 1459, and remained under their occupation until 1804, when Serbia finally managed to regain its sovereignty.

Aftermath

| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2016) |

See also

- Banat in the Middle Ages

- List of medieval Serbian literature

- Medieval Serbian Army

- Medieval Monuments in Kosovo

- History of Medieval Kosovo

References

- Bogdanović 1986, ch. II, para. 2.

- Bogdanović 1986, ch. II, para. 3.

- Bogdanović 1986, ch. II, para. 4.

- Janković, Đorđe (2008). "The Slavs in the 6th century North Illyricum". Belgrade: Faculty of Philosophy.

- Živković 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Blagojević & Petković 1989, p. 19.

- ^ Novaković 2010.

- ^ Moravcsik 1993, pp. 153–155.

- Strizović, Đorđe (2004). Прошлост која живи. Доситеј. p. 19.

- Fine 1991, p. 53.

- Moravcsik 1993, p. 156.

- Živković 2006, pp. 22–23.

- http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/724.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Fine 1994, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 309.

- "Serbian Culture of the 14th Century. Volume I". Dusanov Zakonik. Retrieved 2010-07-25.

- Ćorović 2001, ch. 3, XIII.

- Mihaljčić 1975, pp. 164–165, 220. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMihaljčić1975 (help)

- Fine 1994, pp. 409–411.

- Isabelle Dierauer (16 May 2013). Disequilibrium, Polarization, and Crisis Model: An International Relations Theory Explaining Conflict. University Press of America. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7618-6106-5.

Sources

- Blagojević, Miloš; Petković, Sreten (1989). Srbija u doba Nemanjića: od kneževine do carstva : 1168-1371 : ilustrovana hronika. TRZ "VAJAT".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogdanović, Dimitrije (1986) . "KNJIGA O KOSOVU". SANU; Rastko.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) . "Istorija srpskog naroda" (Internet ed.). Belgrade: Јанус; Ars Libri.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, John Van Antwerp, Jr. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Novaković, Relja (2010) . "Gde se nalazila Srbija od VII do XII veka: Zaključak i rezime monografije" (Internet ed.).

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Živković, Tibor (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу, 600-1025. Историјски институт.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Živković, Tibor (2006). Portreti srpskih vladara (IX—XII vek). Belgrade. pp. 11–20. ISBN 86-17-13754-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Primary

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1993). De Administrando Imperio (Moravcsik, Gyula ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.

Further reading

- Blagojević, M. (1997) Srpske udeone kneževine. Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, br. 36, str. 45-62

- Novaković, S. (1888) Srpske oblasti X i XII veka. Glasnik Srpskog učenog društva, XLVIII, 1-150

- Novaković, S. (1912) Zakonski spomenici srpskih država srednjega veka. Beograd: Srpska kraljevska akademija / SKA

- "О ПРОУЧАВАЊУ И ПУБЛИКОВАЊУ УТВРЂЕНИХ МЕСТА У СРБИЈИ ИЗ VII-X СТОЛЕЋА".

External links

| Preceded byRoman Serbia | Medieval Serbia 476–1540 AD |

Succeeded byOttoman Serbia |

| Serbia articles | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

|  | |||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||

| Economy |

| ||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||