| Revision as of 02:48, 25 October 2004 editStewartMine (talk | contribs)813 edits →References← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:51, 25 October 2004 edit undoWetman (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers92,066 edits →ReferencesNext edit → | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| * Luciano Canfora: ''The Vanished Library. A Wonder of the Ancient World'', trans. Martin Ryle. University of California Press. Berkeley, 1989 ISBN 0520072553 | * Luciano Canfora: ''The Vanished Library. A Wonder of the Ancient World'', trans. Martin Ryle. University of California Press. Berkeley, 1989 ISBN 0520072553 | ||

| ** Further reading: Alexander Stille: |

** Further reading: Alexander Stille: ''The Future of the Past'' chapter "The Return of the Vanished Library". New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. 246-273. | ||

| * Mostafa El-Abbadi: ''Life and fate of the ancient Library of Alexandria''. Paris: UNESCO, 1992 (second, revised edition) ISBN 9231026321 | * Mostafa El-Abbadi: ''Life and fate of the ancient Library of Alexandria''. Paris: UNESCO, 1992 (second, revised edition) ISBN 9231026321 | ||

| * Paulus Orosius: ''The seven books of history against the pagans''. Translated by Roy J. Deferrari. The Catholic University of America, Washington 1964. | * Paulus Orosius: ''The seven books of history against the pagans''. Translated by Roy J. Deferrari. The Catholic University of America, Washington 1964. | ||

Revision as of 05:51, 25 October 2004

The Royal Library of Alexandria was once the largest in the Mediterranean world. It is usually assumed to have been founded at the beginning of the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II of Egypt after his father had set up the Temple of the Muses or Museum. The initial organization is attributed to Demetrius Phalereus. The Library is estimated to have stored at its peak 400,000 to 700,000 scrolls. A new library was inaugurated in 2003 near the site of the old library.

Overview

One story holds that the Library was seeded with Aristotle's own private collection, through one of his students, Demetrius Phalereus. Another concerns how its collection grew so large. By decree of Ptolemy III of Egypt, all visitors to the city were required to surrender all books and scrolls in their possession; these writings were then swiftly copied by official scribes. The originals were put into the Library, and the copies were delivered to the previous owners. While encroaching on the rights of the traveler or merchant, it also helped to create a reservoir of books in the relatively new city.

The Library's contents were likely distributed over several buildings, with the main library either located directly attached to or close to the oldest building, the Museum, and a daughter library in the younger Serapeum, also a temple dedicated to the God Serapis. Edward Parsons provides the following description of the main library based on the existing historical records:

- A covered marble colonnade connected the Museum with an adjacent stately building, also in white marble and stone, architecturally harmonious, indeed forming an integral part of the vast pile, dedicated to learning by the wisdom of the first Ptolemy in following the advice and genius of Demetrios of Phaleron. This was the famous Library of Alexandria, the "Mother" library of the Museum, the Alexandriana, truly the foremost wonder of the ancient world. Here in ten great Halls, whose ample walls were lined with spacious armaria, numbered and titled, were housed the myriad manuscripts containing the wisdom, knowledge, and information, accumulated by the genius of the Hellenic peoples. Each of the ten Halls was assigned to a separate department of learning embracing the assumed ten divisions of Hellenic knowledge as may have been found in the Catalogue of Callimachus of Greek Literature in the Alexandrian Library, the farfamed Pinakes. The Halls were used by the scholars for general research, although there were smaller separate rooms for individuals or groups engaged in special studies.

In 2004 a Polish-Egyptian team claimed to have discovered part of the library while excavating in the Bruchion region. The archaeologists claimed to have found thirteen "lecture halls", each with a central podium. Zahi Hawass, president of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities said that all together, the rooms uncovered so far could have seated 5000 students.

To commemorate the ancient library, the government of Egypt has built a major library and museum complex at Alexandria, called the Bibliotheca Alexandrina(website).

Destruction of the Great Library

One of the reasons so little is known about the Library is that it was lost centuries after its creation. All that is left of many of the volumes are tantalizing titles that hint at all the history lost from the building's destruction. Few events in ancient history are as controversial as the destruction of the Library, as the historical record is both contradictory and incomplete. Not surprisingly, the Great Library became a symbol for knowledge itself, and its destruction was attributed to those who were portrayed as ignorant barbarians, often for purely political reasons.

Much of the debate rests on a different understanding of what constituted the actual Library. Large parts of the Library were likely decentralized, so it is appropriate to also speak of the "Alexandrian libraries". Both the Serapeum, a temple and daughter library, and the Museum itself existed until about 400 CE. Only if one believes the Museum to be distinct from the Great Library, an event of destruction prior to that point becomes plausible.

One account of such an event of destruction concerns Julius Caesar. During his invasion of Alexandria in 47–48 BCE, Caesar set the enemy fleet in the harbor on fire. Some historians believe that this fire spread into the city and destroyed the entire library. While this interpretation is now a minority view, it is based on several ancient sources, all of which were written at least about 150 years after the destruction supposedly took place. Edward Parsons has analyzed the Caesar theory in his book The Alexandrian Library and summarizes the sources as follows:

- A final summary is interesting: of the 16 writers, 10, Caesar himself, the author of the Alexandrian War, Cicero, Strabo, Livy (as far as we know), Lucan, Florus, Suetonius, Appian, and even Athenaeus apparently knew nothing of the burning of the Museum, of the Library, or of Books during Caesar's visit to Egypt; and 6 tell of the incident as follows:

- 1. Seneca (AD 49), the first writer to mention it (and that nearly 100 years after the alleged event), definitely says that 40,000 books were burned.

- 2. Plutarch (c. 117) says that the fire destroyed the great Library.

- 3. Aulus Gellius (123 - 169) says that during the "sack" of Alexandria 700,000 volumes were all burned.

- 4. Dio Cassius (155 - 235) says that storehouses containing grain and books were burned, and that these books were of great number and excellence.

- 5. Ammianus Marcellinus (390) says that in the "sack" of the city 70,000 volumes were burned.

- 6. Orosius (c. 415), the last writer, singularly confirms Seneca as to number and the thing destroyed: 40,000 books.

Of all the sources, Plutarch is the only one to refer explicitly to the destruction of the Library. Plutarch was also the first writer to refer to Caesar by name. Ammianus Marcellinus' account seems to be directly based on Aulus Gellius because the wording is almost the same.

The majority of ancient historians, even those strongly politically opposed to Caesar, give no account of the alleged massive disaster. Cecile Orru argued in "Antike Bibliotheken" (2002, edited by Wolfgang Höpfner) that Caesar cannot have destroyed the Library because it was located in the royal quarter of the city, where Caesar's troops were fortified after the fire (which would not have been possible if the fire had spread to that location).

Furthermore, the Library was a very large stone building and the scrolls were stored away in armaria (and some of them put in capsules), so it is hard to see how a fire in the harbor could have affected a significant part of its contents. Lastly, modern archaeological finds have confirmed an extensive ancient water supply network which covered the major parts of the city, including, of course, the royal quarter.

The destruction of the library is attributed by some historians to a period of civil war in the late 3rd century CE -- but we know that the Museum, which was adjacent to the library, survived until the 4th century. There are also allegations dating to medieval times that claim that Caliph Omar, during an invasion in the 7th century, ordered the Library to be destroyed, but these claims are generally regarded as a Christian attack on Muslims, and include many indications of fabrication, such as the claim that the contents of the Library took six months to burn in Alexandria's public baths. The legend of Caliph Omar's destruction of the library provides the classical example of a dilemma: Omar is reported to have said that if the books of the library did not contain the teachings of the Quran, they were useless and should be destroyed; if the books did contain the teachings of the Quran, they were superfluous and should be destroyed.

Evidence for the existence of the Library after Caesar

As noted above, it is generally accepted that the Museum of Alexandria existed until ca. 400 CE, and if the Museum and the Library are considered to be largely identical or attached to one another, earlier accounts of destruction could only concern a small number of books stored elsewhere. This is consistent with the number given by Seneca, much smaller than the overall volume of books in the Library. So under this interpretation it is plausible that, for example, books stored in a warehouse near the harbor were accidentally destroyed by Caesar, and that larger numbers cited in some works have to be considered unreliable -- misinterpretations by the medieval monks who preserved these works through the Middle Ages, or deliberate forgeries.

Even if one considers the Museum and the Library to be very much separate, there is considerable evidence that the Library continued to exist after the alleged destruction. Plutarch, who claimed the Great Library was destroyed (150 years after the alleged incident), in Life of Antony describes the later transfer of the second largest library to Alexandria by Mark Antony as a gift to Cleopatra. He quotes Calvisius as claiming "that had given her the library of Pergamus, containing two hundred thousand distinct volumes", although he himself finds Calvisius' claims hard to believe. In "Einführung in die Überlieferungsgeschichte" (1994, p. 39), Egert Pöhlmann cites further expansions of the Alexandrian libraries by Caesar Augustus (in the year 12 CE) and Claudius (41-54 CE). Even if the most extreme allegations against Caesar were true, this raises the question of what happened to these volumes.

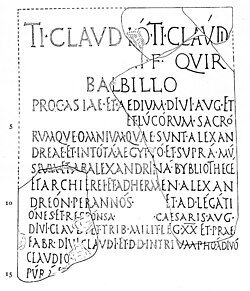

The continued existence of the Library is also supported by an ancient inscription found in the early 20th century, dedicated to Tiberius Claudius Balbillus of Rome (d. 56 CE). As noted in the "Handbuch der Bibliothekswissenschaft" (Georg Leyh, Wiesbaden 1955):

"We have to understand the office which Ti. Claudius Balbillus held , which included the title 'supra Museum et ab Alexandrina bibliotheca', to have combined the direction of the Museum with that of the united libraries, as an academy."

Athenaeus (c. 200 CE) wrote in detail in the Deipnosophistai about the wealth of Ptolemy II (309-246 BC) and the type and number of his ships. When it came to the Library and Museum, he wrote: "Why should I now have to point to the books, the establishment of libraries and the collection in the Museum, when this is in every man's memory?" Given the context of his statement, and the fact that the Museum still existed at the time, it is clear that Athenaeus cannot have referred to any event of destruction -- he considered both facilities to be so famous that it was not necessary for him to describe them in detail. We must therefore conclude that at least some of the Alexandrian libraries were still in operation at the time.

Destruction of the pagan temples by Theophilus

In the late 4th century, persecution of pagans by Christians had reached new levels of intensity. Temples and statues were destroyed throughout the Roman empire, pagan rituals forbidden under punishment of death, and libraries closed. In 391 CE, Emperor Theodosius ordered the destruction of all pagan temples, and the bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, complied with this request. Socrates Scholasticus provides the following account of the destruction of the temples in Alexandria:

- "Demolition of the Idolatrous Temples at Alexandria, and the Consequent Conflict between the Pagans and Christians."

- "At the solicitation of Theophilus bishop of Alexandria the emperor issued an order at this time for the demolition of the heathen temples in that city; commanding also that it should be put in execution under the direction of Theophilus. Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost to expose the pagan mysteries to contempt. And to begin with, he caused the Mithreum to be cleaned out, and exhibited to public view the tokens of its bloody mysteries. Then he destroyed the Serapeum, and the bloody rights of the Mithreum he publicly caricatured; the Serapeum also he showed full of extravagant superstitions, and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum. Thus this disturbance having been terminated, the governor of Alexandria, and the commander-in-chief of the troops in Egypt, assisted Theophilus in demolishing the heathen temples. These were therefore razed to the ground, and the images of their gods molten into pots and other convenient utensils for the use of the Alexandrian church; for the emperor had instructed Theophilus to distribute them for the relief of the poor. All the images were accordingly broken to pieces, except one statue of the god before mentioned, which Theophilus preserved and set up in a public place; `Lest,' said he, `at a future time the heathens should deny that they had ever worshiped such gods.'"

The Serapeum housed part of the Library, but it is not known how many books were contained in it at the time of destruction. Notably, Paulus Orosius admitted in his History against the pagans: "oday there exist in temples book chests which we ourselves have seen, and, when these temples were plundered, these, we are told, were emptied by our own men in our time, which, indeed, is a true statement." This indicates that any books that existed in the Serapeum at the time were destroyed when it was razed to the ground.

As for the Museum, Mostafa El-Abbadi writes in Life and Fate of the ancient Library of Alexandria (Paris 1992):

- "The Mouseion, being at the same time a 'shrine of the Muses', enjoyed a degree of sanctity as long as other pagan temples remained unmolested. Synesius of Cyrene, who studied under Hypatia at the end of the fourth century, saw the Mouseion and described the images of the philosophers in it. We have no later reference to its existence in the fifth century. As Theon, the distinguished mathematician and father of Hypatia, herself a renowned scholar, was the last recorded scholar-member (c. 380), it is likely that the Mouseion did not long survive the promulgation of Theodosius' decree in 391 to destroy all pagan temples in the City."

Conclusions

There is a growing consensus among historians that the Library of Alexandria likely suffered from several destructive events, but that the destruction of Alexandria's pagan temples in the late 4th century was probably the most severe and final one. The evidence for that destruction is the most definitive and secure. Caesar's invasion may well have led to the loss of some 40,000-70,000 scrolls in a warehouse adjacent to the port (as Luciano Canfora argues, they were likely copies produced by the Library intended for export), but it is unlikely to have affected the Library or Museum, given that there is ample evidence that both existed later.

Civil wars, decreasing investments in maintenance and acquisition of new scrolls and generally declining interest in non-religious pursuits likely contributed to a reduction in the body of material available in the Library, especially in the fourth century. The Serapeum was certainly destroyed by Theophilus in 391, and the Museum and Library may have fallen victim to the same campaign.

If indeed a Christian mob was responsible for the destruction of the Library, the question remains why Plutarch casually referred to the destruction of "the great library" by Caesar in his Life of Caesar. It is important to note that most surviving ancient works, including Plutarch, were copied throughout the Middle Ages by Christian monks. During this copying process, errors have sometimes been made, and some have argued that deliberate forgery is not out of the question, especially for politically sensitive issues. Other explanations are certainly possible, and the fate of the Library will continue to be the subject of much heated historical debate.

Other libraries of the ancient world

- The library of King Ashurbanipal, in Nineveh— Considered to be "the first systematically collected library", it was rediscovered in the 19th century. While the library had been destroyed, many fragments of the ancient cuneiform tables survived, and have been reconstructed. Large portions of the Epic of Gilgamesh were among the many finds.

- The Villa of the Papyri, in Herculaneum— One of the largest libraries of ancient Rome. Thought to have been destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Rediscovered in 1752, the contents of the library were found to have been carbonized. Using modern techniques, the scrolls are currently being meticulously unrolled, and the writing deciphered.

- At Pergamum the Attalid kings formed the second best classical library after Alexandria, founded in emulation of the Ptolemies. When the Ptolemies stopped exporting papyrus, partly because of competitors and partly because of shortages, the Pergamenes invented a new substance to use in codices, called pergamum or parchment after the city. This was made of fine calfskin, a predecessor of vellum and paper.

- Caesarea Palaestina had a great early Christian library. Through Origen and the scholarly priest Pamphilus, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory, Basil the Great, Jerome and others came to study there.

References

- Luciano Canfora: The Vanished Library. A Wonder of the Ancient World, trans. Martin Ryle. University of California Press. Berkeley, 1989 ISBN 0520072553

- Further reading: Alexander Stille: The Future of the Past chapter "The Return of the Vanished Library". New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. 246-273.

- Mostafa El-Abbadi: Life and fate of the ancient Library of Alexandria. Paris: UNESCO, 1992 (second, revised edition) ISBN 9231026321

- Paulus Orosius: The seven books of history against the pagans. Translated by Roy J. Deferrari. The Catholic University of America, Washington 1964.

- Edward Parsons: The Alexandrian Library. London, 1952. Relevant online excerpt.

External links

- Ellen N. Brundige: "The Library of Alexandria"

- James Hannam: "The Mysterious Fate of the Great Library of Alexandria" and "The Foundation and Loss of the Royal and Serapeum Libraries of Alexandria". Hannam, "a member of the Christian Cadre of internet apologists", analyzes the destruction of the Library and concludes that Caesar is most likely to be responsible.

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina