| Revision as of 08:55, 15 May 2017 editInternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers5,387,806 edits Rescuing 3 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.3.1.1)← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:33, 16 May 2017 edit undoKarlfonza (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users881 editsm →Special librariesNext edit → | ||

| Line 257: | Line 257: | ||

| Some special libraries, such as governmental law libraries, hospital libraries, and military base libraries commonly are open to public visitors to the institution in question. Depending on the particular library and the clientele it serves, special libraries may offer services similar to research, reference, public, academic, or children's libraries, often with restrictions such as only lending books to patients at a hospital or restricting the public from parts of a military collection. Given the highly individual nature of special libraries, visitors to a special library are often advised to check what services and restrictions apply at that particular library. | Some special libraries, such as governmental law libraries, hospital libraries, and military base libraries commonly are open to public visitors to the institution in question. Depending on the particular library and the clientele it serves, special libraries may offer services similar to research, reference, public, academic, or children's libraries, often with restrictions such as only lending books to patients at a hospital or restricting the public from parts of a military collection. Given the highly individual nature of special libraries, visitors to a special library are often advised to check what services and restrictions apply at that particular library. | ||

| ] | |||

| Special libraries are distinguished from ], which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and other special materials, though some special libraries have special collections of their own, typically related to the library's specialized subject area. | Special libraries are distinguished from ], which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and other special materials, though some special libraries have special collections of their own, typically related to the library's specialized subject area. | ||

Revision as of 17:33, 16 May 2017

For other uses, see Library (disambiguation).

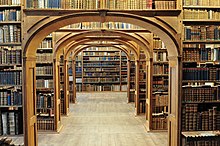

A library is a collection of sources of information and similar resources, made accessible to a defined community for reference or borrowing. It provides physical or digital access to material, and may be a physical building or room, or a virtual space, or both. A library's collection can include books, periodicals, newspapers, manuscripts, films, maps, prints, documents, microform, CDs, cassettes, videotapes, DVDs, Blu-ray Discs, e-books, audiobooks, databases, and other formats. Libraries range in size from a few shelves of books to several million items. In Latin and Greek, the idea of a bookcase is represented by Bibliotheca and Bibliothēkē (Greek: βιβλιοθήκη): derivatives of these mean library in many modern languages, e.g. French bibliothèque.

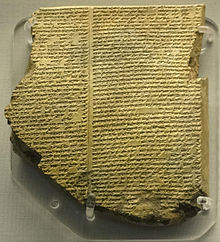

The first libraries consisted of archives of the earliest form of writing—the clay tablets in cuneiform script discovered in Sumer, some dating back to 2600 BC. Private or personal libraries made up of written books appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. In the 6th century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria.

A library is organized for use and maintained by a public body, an institution, a corporation, or a private individual. Public and institutional collections and services may be intended for use by people who choose not to—or cannot afford to—purchase an extensive collection themselves, who need material no individual can reasonably be expected to have, or who require professional assistance with their research. In addition to providing materials, libraries also provide the services of librarians who are experts at finding and organizing information and at interpreting information needs. Libraries often provide quiet areas for studying, and they also often offer common areas to facilitate group study and collaboration. Libraries often provide public facilities for access to their electronic resources and the Internet. Modern libraries are increasingly being redefined as places to get unrestricted access to information in many formats and from many sources. They are extending services beyond the physical walls of a building, by providing material accessible by electronic means, and by providing the assistance of librarians in navigating and analyzing very large amounts of information with a variety of digital tools.

History

Main article: History of librariesEarly libraries

The first libraries consisted of archives of the earliest form of writing—the clay tablets in cuneiform script discovered in temple rooms in Sumer, some dating back to 2600 BC. These archives, which mainly consisted of the records of commercial transactions or inventories, mark the end of prehistory and the start of history.

Things were much the same in the government and temple records on papyrus of Ancient Egypt. The earliest discovered private archives were kept at Ugarit; besides correspondence and inventories, texts of myths may have been standardized practice-texts for teaching new scribes. There is also evidence of libraries at Nippur about 1900 BC and those at Nineveh about 700 BC showing a library classification system.

Over 30,000 clay tablets from the Library of Ashurbanipal have been discovered at Nineveh, providing modern scholars with an amazing wealth of Mesopotamian literary, religious and administrative work. Among the findings were the Enuma Elish, also known as the Epic of Creation, which depicts a traditional Babylonian view of creation, the Epic of Gilgamesh, a large selection of "omen texts" including Enuma Anu Enlil which "contained omens dealing with the moon, its visibility, eclipses, and conjunction with planets and fixed stars, the sun, its corona, spots, and eclipses, the weather, namely lightning, thunder, and clouds, and the planets and their visibility, appearance, and stations", and astronomic/astrological texts, as well as standard lists used by scribes and scholars such as word lists, bilingual vocabularies, lists of signs and synonyms, and lists of medical diagnoses.

Philosopher Laozi was keeper of books in the earliest library in China, which belonged to the Imperial Zhou dynasty. Also, evidence of catalogues found in some destroyed ancient libraries illustrates the presence of librarians.

Classical period

The Library of Alexandria, in Egypt, was the largest and most significant great library of the ancient world. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library was conceived and opened either during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC) or during the reign of his son Ptolemy II (283–246 BC). An early organization system was in effect at Alexandria.

The Library of Celsus in Ephesus, Anatolia, now part of Selçuk, Turkey was built in honor of the Roman Senator Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (completed in 135) by Celsus’ son, Gaius Julius Aquila (consul, 110 AD). The library was built to store 12,000 scrolls and to serve as a monumental tomb for Celsus.

Private or personal libraries made up of written books (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. The celebrated book collectors of Hellenistic Antiquity were listed in the late 2nd century in Deipnosophistae. All these libraries were Greek; the cultivated Hellenized diners in Deipnosophistae pass over the libraries of Rome in silence. By the time of Augustus, there were public libraries near the forums of Rome: there were libraries in the Porticus Octaviae near the Theatre of Marcellus, in the temple of Apollo Palatinus, and in the Bibliotheca Ulpiana in the Forum of Trajan. The state archives were kept in a structure on the slope between the Roman Forum and the Capitoline Hill.

Private libraries appeared during the late republic: Seneca inveighed against libraries fitted out for show by illiterate owners who scarcely read their titles in the course of a lifetime, but displayed the scrolls in bookcases (armaria) of citrus wood inlaid with ivory that ran right to the ceiling: "by now, like bathrooms and hot water, a library is got up as standard equipment for a fine house (domus). Libraries were amenities suited to a villa, such as Cicero's at Tusculum, Maecenas's several villas, or Pliny the Younger's, all described in surviving letters. At the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, apparently the villa of Caesar's father-in-law, the Greek library has been partly preserved in volcanic ash; archaeologists speculate that a Latin library, kept separate from the Greek one, may await discovery at the site.

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the Roman Empire as each succeeding emperor strove to open one or many which outshone that of his predecessor. Rome’s first public library was established by Asinius Pollio. Pollio was a lieutenant of Julius Caesar and one of his most ardent supporters. After his military victory in Illyria, Pollio felt he had enough fame and fortune to create what Julius Caesar had sought for a long time: a public library to increase the prestige of Rome and rival the one in Alexandria. Pollios’s library, the Anla Libertatis, which was housed in the Atrium Libertatis, was centrally located near the Forum Romanum. It was the first to employ an architectural design that separated works into Greek and Latin. All subsequent Roman public libraries will have this design. At the conclusion of Rome’s civil wars following the death of Marcus Antonius in 30 BC, the Emperor Augustus sought to reconstruct many of Rome’s damaged buildings. During this construction, Augustus created two more public libraries. The first was the library of the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine, often called the Palatine library, and the second was the library of the Porticus of Octaviae.

Two more libraries were added by the Emperor Tiberius on Palatine Hill and one by Vespasian after 70 AD. Vespasian’s library was constructed in the Forum of Vespasian, also known as the Forum of Peace, and became one of Rome’s principal libraries. The Bibliotheca Pacis was built along the traditional model and had two large halls with rooms for Greek and Latin libraries containing the works of Galen and Lucius Aelius. One of the best preserved was the ancient Ulpian Library built by the Emperor Trajan. Completed in 112/113, the Ulpian Library was part of Trajan’s Forum built on the Capitoline Hill. Trajan’s Column separated the Greek and Latin rooms which faced each other. The structure was approximately fifty feet high with the peak of the roof reaching almost seventy feet.

Unlike the Greek libraries, readers had direct access to the scrolls, which were kept on shelves built into the walls of a large room. Reading or copying was normally done in the room itself. The surviving records give only a few instances of lending features. Most of the large Roman baths were also cultural centres, built from the start with a library, a two-room arrangement with one room for Greek and one for Latin texts.

Libraries were filled with parchment scrolls as at Library of Pergamum and on papyrus scrolls as at Alexandria: the export of prepared writing materials was a staple of commerce. There were a few institutional or royal libraries which were open to an educated public (such as the Serapeum collection of the Library of Alexandria, once the largest library in the ancient world), but on the whole collections were private. In those rare cases where it was possible for a scholar to consult library books, there seems to have been no direct access to the stacks. In all recorded cases, the books were kept in a relatively small room where the staff went to get them for the readers, who had to consult them in an adjoining hall or covered walkway.

Han Chinese scholar Liu Xiang established the first library classification system during the Han dynasty, and the first book notation system. At this time, the library catalogue was written on scrolls of fine silk and stored in silk bags.

Late Antiquity

During the Late Antiquity and Middle Ages periods, there was no Rome of the kind that ruled the Mediterranean for centuries and spawned the culture that produced twenty-eight public libraries in the urbs Roma. The empire had been divided then later re-united again under Constantine the Great who moved the capital of the Roman Empire in 330 AD to the city of Byzantium which was renamed Constantinople. The Roman intellectual culture that flourished in ancient times was undergoing a transformation as the academic world moved from laymen to Christian clergy. As the West crumbled, books and libraries flourished and flowed east toward the Byzantine Empire. There, four different types of libraries were established: imperial, patriarchal, monastic, and private. Each had its own purpose and, as a result, their survival varied.

Christianity was a new force in Europe and many of the faithful saw Hellenistic culture as pagan. As such, many classical Greek works, written on scrolls, were left to decay as only Christian texts were thought fit for preservation in a codex, the progenitor of the modern book. In the East, however, this was not the case as many of these classical Greek and Roman texts were copied.

In Byzantium, much of this work devoted to preserving Hellenistic thought in codex form was performed in scriptoriums by monks. While monastic library scriptoriums flourished throughout the East and West, the rules governing them were generally the same. Barren and sun-lit rooms (because candles were a source of fire) were major features of the scriptorium that was both a model of production and monastic piety. Monks scribbled away for hours a day, interrupted only by meals and prayers. With such production, medieval monasteries began to accumulate large libraries. These libraries were devoted solely to the education of the monks and were seen as essential to their spiritual development. Although most of these texts that were produced were Christian in nature, many monastic leaders saw common virtues in the Greek classics. As a result, many of these Greek works were copied, and thus saved, in monastic scriptoriums.

When Europe passed into the Dark Ages, Byzantine scriptoriums laboriously preserved Greco-Roman classics. As a result, Byzantium revived Classical models of education and libraries. The Imperial Library of Constantinople was an important depository of ancient knowledge. Constantine himself wanted such a library but his short rule denied him the ability to see his vision to fruition. His son Constantius II made this dream a reality and created an imperial library in a portico of the royal palace. He ruled for 24 years and accelerated the development of the library and the intellectual culture that came with such a vast accumulation of books.

Constantius II appointed Themistius, a pagan philosopher and teacher, as chief architect of this library building program. Themistius set about a bold program to create an imperial public library that would be the centerpiece of the new intellectual capital of Constantinople. Classical authors such as Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Isocrates, Thucydides, Homer, and Zeno were sought. Themeistius hired calligraphers and craftsman to produce the actual codices. He also appointed educators and created a university-like school centered around the library.

After the death of Constantius II, Julian the Apostate, a bibliophile intellectual, ruled briefly for less than three years. Despite this, he had a profound impact on the imperial library and sought both Christian and pagan books for its collections. Later, the Emperor Valens hired Greek and Latin scribes full-time with funds from the royal treasury to copy and repair manuscripts.

At its height in the 5th century, the Imperial Library of Constantinople had 120,000 volumes and was the largest library in Europe. A fire in 477 consumed the entire library but it was rebuilt only to be burned again in 726, 1204, and in 1453 when Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks.

Patriarchal libraries fared no better, and sometimes worse, than the Imperial Library. The Library of the Patriarchate of Constantinople was founded most likely during the reign of Constantine the Great in the 4th century. As a theological library, it was known to have employed a library classification system. It also served as a repository of several ecumenical councils such as the Council of Nicea, Council of Ephesus, and the Council of Chalcedon. The library, which employed a librarian and assistants, may have been originally located in the Patriarch’s official residence before it was moved to the Thomaites Triclinus in the 7th century. While much is not known about the actual library itself, it is known that many of its contents were subject to destruction as religious in-fighting ultimately resulted in book burnings.

During this period, small private libraries existed. Many of these were owned by church members and the aristocracy. Teachers also were known to have small personal libraries as well as wealthy bibliophiles who could afford the highly ornate books of the period.

Thus, in the 6th century, at the close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria. Cassiodorus, minister to Theodoric, established a monastery at Vivarium in the toe of Italy (modern Calabria) with a library where he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus not only collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of reading and methods for copying texts accurately. In the end, however, the library at Vivarium was dispersed and lost within a century.

Through Origen and especially the scholarly presbyter Pamphilus of Caesarea, an avid collector of books of Scripture, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil the Great, Jerome, and others came and studied there.

Islamic lands

By the 8th century, first Iranians and then Arabs had imported the craft of papermaking from China, with a paper mill already at work in Baghdad in 794. Early paper was called bagdatikos, meaning "from Baghdad", because it was introduced to the west mainly by this city. By the 9th century, public libraries started to appear in many Islamic cities. They were called "house of knowledge" or dar al-'ilm. They were each endowed by Islamic sects with the purpose of representing their tenets as well as promoting the dissemination of secular knowledge. The 9th-century Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil of Iraq, ordered the construction of a "zawiyat qurra" – an enclosure for readers which was "lavishly furnished and equipped". In Shiraz, Adhud al-Daula (d. 983) set up a library, described by the medieval historian, al-Muqaddasi, as "a complex of buildings surrounded by gardens with lakes and waterways. The buildings were topped with domes, and comprised an upper and a lower story with a total, according to the chief official, of 360 rooms.... In each department, catalogues were placed on a shelf... the rooms were furnished with carpets". The libraries often employed translators and copyists in large numbers, in order to render into Arabic the bulk of the available Persian, Greek, Roman and Sanskrit non-fiction and the classics of literature.

Organization was a strength of Islamic Libraries during the Golden Age (7th -14th century). In this period, books were organized by subject. Within the subject, the materials were further organized by when the libraries gained the item, not by last name of the author or the title of the book. Also, Islamic libraries may be the first to have implemented a catalogue of owned materials. The content of a bookshelf was recorded on paper and attached to the end of shelf. Arab-Islamic people also were very favorable of public knowledge. Public libraries were very popular along with mosque, private, and academic libraries. Instead of only societies most elite, such as caliphs and princes, information was something that was offered to everyone. Some of the libraries were said to let patrons check out up to 200 items. These buildings were also made for comfort of the readers and information seekers. It was said that the rooms had carpets for sitting and reading comfortably. Also, openings such as doors and windows were secured closed as to protect patrons against cold drafts.

This flowering of Islamic learning ceased centuries later when learning began declining in the Islamic world, after many of these libraries were destroyed by Mongol invasions. Others were victim of wars and religious strife in the Islamic world. However, a few examples of these medieval libraries, such as the libraries of Chinguetti in West Africa, remain intact and relatively unchanged. Another ancient library from this period which is still operational and expanding is the Central Library of Astan Quds Razavi in the Iranian city of Mashhad, which has been operating for more than six centuries.

The contents of these Islamic libraries were copied by Christian monks in Muslim/Christian border areas, particularly Spain and Sicily. From there they eventually made their way into other parts of Christian Europe. These copies joined works that had been preserved directly by Christian monks from Greek and Roman originals, as well as copies Western Christian monks made of Byzantine works. The resulting conglomerate libraries are the basis of every modern library today.

Buddhist scriptures, educational materials, and histories were stored in libraries in pre-modern Southeast Asia. In Burma, a royal library called the Pitakataik was legendarily founded by King Anawrahta; in the 18th century, British envoy Michael Symes, on visiting this library, wrote that "it is not improbable that his Birman majesty may possess a more numerous library than any potentate, from the banks of the Danube to the borders of China". In Thailand, libraries called ho trai were built throughout the country, usually on stilts above a pond to prevent bugs from eating at the books.

Islam

The centrality of the Qurʾān as the prototype of the written word in Islam bears significantly on the role of books within its intellectual tradition and educational system. An early impulse in Islam was to manage reports of events, key figures and their sayings and actions. Thus, "the onus of being the last 'People of the Book' engendered an ethos of " early on and the establishment of important book repositories throughout the Muslim world has occurred ever since.

Upon the spread of Islam, libraries in newly Islamic lands knew a brief period of expansion in the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily, and Spain. Like the Christian libraries, they mostly contained books which were made of paper, and took a codex or modern form instead of scrolls; they could be found in mosques, private homes, and universities, from Timbuktu to Afghanistan and modern day Pakistan. In Aleppo, for example, the largest and probably the oldest mosque library, the Sufiya, located at the city's Grand Umayyad Mosque, contained a large book collection of which 10,000 volumes were reportedly bequeathed by the city's most famous ruler, Prince Sayf al-Dawla. Ibn al-Nadim's bibliography Fihrist demonstrates the devotion of medieval Muslim scholars to books and reliable sources; it contains a description of thousands of books circulating in the Islamic world circa 1000, including an entire section for books about the doctrines of other religions. Modern Islamic libraries for the most part do not hold these antique books; many were lost, destroyed by Mongols, or removed to European libraries and museums during the colonial period.

European Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, monastery libraries developed, such as the important one at the Abbey of Montecassino in Italy. Books were usually chained to the shelves, reflecting the fact that manuscripts, which were created via the labour-intensive process of hand copying, were valuable possessions. This hand-copying was often accomplished by travelling monks who made the treks to the sources of knowledge and illumination they sought for learning or to copy the manuscripts held by other monasteries for their own monastic libraries.

Despite this protectiveness, many libraries loaned books if provided with security deposits (usually money or a book of equal value). Lending was a means by which books could be copied and spread. In 1212, the council of Paris condemned those monasteries that still forbade loaning books, reminding them that lending is "one of the chief works of mercy." The early libraries located in monastic cloisters and associated with scriptoria were collections of lecterns with books chained to them. Shelves built above and between back-to-back lecterns were the beginning of bookpresses. The chain was attached at the fore-edge of a book rather than to its spine. Book presses came to be arranged in carrels (perpendicular to the walls and therefore to the windows) in order to maximize lighting, with low bookcases in front of the windows. This "stall system" (i.e. fixed bookcases perpendicular to exterior walls pierced by closely spaced windows) was characteristic of English institutional libraries. In European libraries, bookcases were arranged parallel to and against the walls. This "wall system" was first introduced on a large scale in Spain's El Escorial.

Also, in Eastern Christianity monastery libraries kept important manuscripts. The most important of them were the ones in the monasteries of Mount Athos for Orthodox Christians, and the library of the Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt for the Coptic Church.

Renaissance

From the 15th century in central and northern Italy, libraries of humanists and their enlightened patrons provided a nucleus around which an "academy" of scholars congregated in each Italian city of consequence. Malatesta Novello, lord of Cesena, founded the Malatestiana Library. Cosimo de' Medici in Florence established his own collection, which formed the basis of the Laurentian Library. In Rome, the papal collections were brought together by Pope Nicholas V, in separate Greek and Latin libraries, and housed by Pope Sixtus IV, who consigned the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana to the care of his librarian, the humanist Bartolomeo Platina in February 1475.

In the 16th century, Sixtus V bisected Bramante's Cortile del Belvedere with a cross-wing to house the Apostolic Library in suitable magnificence. The 16th and 17th centuries saw other privately endowed libraries assembled in Rome: the Vallicelliana, formed from the books of Saint Filippo Neri, with other distinguished libraries such as that of Cesare Baronio, the Biblioteca Angelica founded by the Augustinian Angelo Rocca, which was the only truly public library in Counter-Reformation Rome; the Biblioteca Alessandrina with which Pope Alexander VII endowed the University of Rome; the Biblioteca Casanatense of the Cardinal Girolamo Casanata; and finally the Biblioteca Corsiniana founded by the bibliophile Clement XII Corsini and his nephew Cardinal Neri Corsini, still housed in Palazzo Corsini in via della Lungara. The Republic of Venice patronized the foundation of the Biblioteca Marciana, based on the library of Cardinal Basilios Bessarion. In Milan, Cardinal Federico Borromeo founded the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

This trend soon spread outside of Italy, for example Louis III, Elector Palatine founded the Bibliotheca Palatina of Heidelberg.

These libraries don't have as many volumes as the modern libraries. However, they keep many valuable manuscripts of Greek, Latin, and Biblical works.

Tianyi Chamber, founded in 1561 by Fan Qin during the Ming dynasty, is the oldest existing library in China. In its heyday, it boasted a collection of 70,000 volumes of antique books.

Enlightenment era libraries

The 17th and 18th centuries include what is known as a golden age of libraries; during this some of the more important libraries were founded in Europe. Francis Trigge Chained Library of St. Wulfram's Church, Grantham, Lincolnshire was founded in 1598 by the rector of nearby Welbourne. Thomas Bodley founded the Bodleian Library, which was open to the "whole republic of the learned", Norwich City library was established in 1608, and the British Library was established in 1753. Chetham's Library in Manchester, which claims to be the oldest public library in the English-speaking world, opened in 1653. Other early town libraries of the UK include those of Ipswich (1612), Bristol (founded in 1613 and opened in 1615), and Leicester (1632). Shrewsbury School also opened its library to townsfolk. The Mazarine Library and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève were founded in Paris, the Austrian National Library in Vienna, the National Central Library in Florence, the Prussian State Library in Berlin, the Załuski Library in Warsaw, and the M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library in St Petersburg.

At the start of the 18th century, libraries were becoming increasingly public and were more frequently lending libraries. The 18th century saw the switch from closed parochial libraries to lending libraries. Before this time, public libraries were parochial in nature and libraries frequently chained their books to desks. Libraries also were not uniformly open to the public.

Even though the British Museum existed at this time and contained over 50,000 books, the national library was not open to the public, or even to a majority of the population. Access to the Museum depended on passes, of which there was sometimes a waiting period of three to four weeks. Moreover, the library was not open to browsing. Once a pass to the library had been issued, the reader was taken on a tour of the library. Many readers complained that the tour was much too short.

Subscription libraries

Main article: Subscription library

At the start of the 19th century, there were virtually no public libraries in the sense in which we now understand the term i.e. libraries provided from public funds and freely accessible to all. Only one important library in Britain, namely Chetham's Library in Manchester, was fully and freely accessible to the public. However, there had come into being a whole network of library provision on a private or institutional basis.

The increase in secular literature at this time encouraged the spread of lending libraries, especially the commercial subscription libraries. Many small, private book clubs evolved into subscription libraries, charging high annual fees or requiring subscribing members to purchase shares in the libraries. The materials available to subscribers tended to focus on particular subject areas, such as biography, history, philosophy, theology, and travel, rather than works of fiction, particularly the novel.

Unlike a public library, access was often restricted to members. Some of the earliest such institutions were founded in late 17th century England, such as Chetham's Library in 1653, Innerpeffray Library in 1680, and Thomas Plume's Library in 1704. In the American colonies, the Library Company of Philadelphia was started in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia.

Parochial libraries attached to Anglican parishes or Nonconformist chapels in Britain emerged in the early 18th century, and prepared the way for local public libraries.

The increasing production and demand for fiction promoted by commercial markets led to the rise of circulating libraries, which met a need that subscription libraries did not fulfil. William Bathoe claimed that his commercial venture was ‘the Original Circulating library’, opening doors at two locations in London in 1737. Circulating libraries also charged subscription fees to users and offered serious subject matter as well as the popular novels, thus the difficulty in clearly distinguishing circulating from subscription libraries.

Subscription libraries were democratic in nature; created by and for communities of local subscribers who aimed to establish permanent collections of books and reading materials, rather than selling their collections annually as the circulating libraries tended to do, in order to raise funds to support their other commercial interests. Even though the subscription libraries were often founded by reading societies, committees, elected by the subscribers, chose books for the collection that were general, rather than aimed at a particular religious, political or professional group. The books selected for the collection were chosen because they would be mutually beneficial to the shareholders. The committee also selected the librarians who would manage the circulation of materials.

In Britain, there were more than 200 commercial circulating libraries open in 1800, more than twice the number of subscription and private proprietary libraries that were operating at the same time. Many proprietors pandered to the most fashionable clientele, making much ado about the sort of shop they offered, the lush interiors, plenty of room and long hours of service. "These 'libraries' would be called rental collections today."

Private libraries

Private subscription libraries functioned in much the same manner as commercial subscription libraries, though they varied in many important ways. One of the most popular versions of the private subscription library was a gentleman's only library. Membership was restricted to the proprietors or shareholders, and ranged from a dozen or two to between four and five hundred.

The Liverpool Subscription Library was a gentlemen only library. In 1798, it was renamed the Athenaeum when it was rebuilt with a newsroom and coffeehouse. It had an entrance fee of one guinea and annual subscription of five shillings. An analysis of the registers for the first twelve years provides glimpses of middle-class reading habits in a mercantile community at this period. The largest and most popular sections of the library were History, Antiquities, and Geography, with 283 titles and 6,121 borrowings, and Belles Lettres, with 238 titles and 3,313 borrowings.

Private subscription libraries held a greater amount of control over both membership and the types of books in the library. There was almost a complete elimination of cheap fiction in the private societies. Subscription libraries prided themselves on respectability. The highest percentage of subscribers were often landed proprietors, gentry, and old professions.

Towards the end of the 18th century and in the first decades of the nineteenth, the need for books and general education made itself felt among social classes created by the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. The late 18th century saw a rise in subscription libraries intended for the use of tradesmen. In 1797, there was established at Kendal what was known as the Economical Library, "designed principally for the use and instruction of the working classes." There was also the Artizans' library established at Birmingham in 1799. The entrance fee was 3 shillings. The subscription was 1 shilling 6 pence per quarter. This was a library of general literature. Novels, at first excluded, were afterwards admitted on condition that they did not account for more than one-tenth of the annual income.

National libraries

Main article: National library

The first national libraries had their origins in the royal collections of the sovereign or some other supreme body of the state.

One of the first plans for a national library was devised by the Welsh mathematician John Dee, who in 1556 presented Mary I of England with a visionary plan for the preservation of old books, manuscripts and records and the founding of a national library, but his proposal was not taken up.

The first true national library was founded in 1753 as part of the British Museum. This new institution was the first of a new kind of museum – national, belonging to neither church nor king, freely open to the public and aiming to collect everything. The museum's foundations lay in the will of the physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane, who gathered an enviable collection of curiosities over his lifetime which he bequeathed to the nation for £20,000.

Sloane's collection included some 40,000 printed books and 7,000 manuscripts, as well as prints and drawings. The British Museum Act 1753 also incorporated the Cotton library and the Harleian library. These were joined in 1757 by the Royal Library, assembled by various British monarchs.

In France, the first national library was the Bibliothèque Mazarine, which evolved from its origin as a royal library founded at the Louvre Palace by Charles V in 1368. The appointment of Jacques Auguste de Thou as librarian in the 17th century, initiated a period of development that made it the largest and richest collection of books in the world. The library opened to the public in 1692, under the administration of Abbé Louvois, Minister Louvois's son. Abbé Louvois was succeeded by the Abbé Bignon, or Bignon II as he was termed, who instituted a complete reform of the library's system. Catalogues were made, which appeared from 1739 to 1753 in 11 volumes. The collections increased steadily by purchase and gift to the outbreak of the French Revolution, at which time it was in grave danger of partial or total destruction, but owing to the activities of Antoine-Augustin Renouard and Joseph Van Praet it suffered no injury.

The library's collections swelled to over 300,000 volumes during the radical phase of the French Revolution when the private libraries of aristocrats and clergy were seized. After the establishment of the French First Republic in September 1792, "the Assembly declared the Bibliotheque du Roi to be national property and the institution was renamed the Bibliothèque Nationale. After four centuries of control by the Crown, this great library now became the property of the French people."

Modern public library

Main article: Public library

Although by the mid-19th century, England could claim 274 subscription libraries and Scotland, 266, the foundation of the modern public library system in Britain is the Public Libraries Act 1850. The Act first gave local boroughs the power to establish free public libraries and was the first legislative step toward the creation of an enduring national institution that provides universal free access to information and literature. In the 1830s, at the height of the Chartist movement, there was a general tendency towards reformism in the United Kingdom. The Capitalist economic model had created a significant amount of free time for workers, and the middle classes were concerned that the workers’ free time was not being well-spent. This was prompted more by Victorian middle class paternalism rather than by demand from the lower social orders. Campaigners felt that encouraging the lower classes to spend their free time on morally uplifting activities, such as reading, would promote greater social good.

In 1835, and against government opposition, James Silk Buckingham, MP for Sheffield and a supporter of the temperance movement, was able to secure the Chair of the Select Committee which would examine "the extent, causes, and consequences of the prevailing vice of intoxication among the labouring classes of the United Kingdom" and propose solutions. Francis Place, a campaigner for the working class, agreed that "the establishment of parish libraries and district reading rooms, and popular lectures on subjects both entertaining and instructive to the community might draw off a number of those who now frequent public houses for the sole enjoyment they afford". Buckingham introduced to Parliament a Public Institution Bill allowing boroughs to charge a tax to set up libraries and museums, the first of its kind. Although this did not become law, it had a major influence on William Ewart MP and Joseph Brotherton MP, who introduced a bill which would “ boroughs with a population of 10,000 or more to raise a ½d for the establishment of museums”. This became the Museums Act 1845.

The advocacy of Ewart and Brotherton then succeeded in having a select committee set up to consider public library provision. The Report argued that the provision of public libraries would steer people towards temperate and moderate habits. With a view to maximising the potential of current facilities, the Committee made two significant recommendations. They suggested that the government should issue grants to aid the foundation of libraries and that the Museums Act 1845 should be amended and extended to allow for a tax to be levied for the establishment of public libraries. The Bill passed through Parliament as most MPs felt that public libraries would provide facilities for self-improvement through books and reading for all classes, and that the greater levels of education attained by providing public libraries would result in lower crime rates.

The earliest example in England of a library to be endowed for the benefit of users who were not members of an institution such as a cathedral or college was the Francis Trigge Chained Library in Grantham, Lincolnshire, established in 1598. The library still exists and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of later public library systems. The beginning of the modern, free, open access libraries really got its start in the UK in 1847. Parliament appointed a committee, led by William Ewart, on Public Libraries to consider the necessity of establishing libraries through the nation: In 1849, their report noted the poor condition of library service, it recommended the establishment of free public libraries all over the country, and it led to the Public Libraries Act in 1850, which allowed all cities with populations exceeding 10,000 to levy taxes for the support of public libraries.

Salford Museum and Art Gallery first opened in November 1850 as "The Royal Museum & Public Library", as the first unconditionally free public library in England. The library in Campfield, Manchester was the first library to operate a free lending library without subscription in 1852. Norwich lays claims to being the first municipality to adopt the Public Libraries Act 1850 (which allowed any municipal borough with a population of 100,000 or more to introduce a halfpenny rate to establish public libraries—although not to buy books). Norwich was the eleventh library to open, in 1857, after Winchester, Manchester, Liverpool, Bolton, Kidderminster, Cambridge, Birkenhead, and Sheffield.

Another important act was the Education Act 1870, which increased literacy and thereby the demand for libraries. By 1877, more than 75 cities had established free libraries, and by 1900 the number had reached 300. This finally marks the start of the public library as we know it. And these acts influenced similar laws in other countries, such as the US. The first tax-supported public library in the United States was Peterborough, New Hampshire (1833) first supported by state funds then an "Act Providing for the Establishment of Public Libraries" in 1849.

Expansion

The year 1876 is key in the history of librarianship in the United States. The American Library Association was formed, as well as The American Library Journal, Melvil Dewey published his decimal-based system of classification, and the United States Bureau of Education published its report, "Public libraries in the United States of America; their history, condition, and management." During the post-Civil War years, there was a rise in the establishment of public libraries, a movement led chiefly by newly formed women's clubs. They contributed their own collections of books, conducted lengthy fund raising campaigns for buildings, and lobbied within their communities for financial support for libraries, as well as with legislatures and the Carnegie Library Endowment founded in the 20th century. They led the establishment of 75–80 percent of the libraries in communities across the country.

Philanthropists and businessmen, including John Passmore Edwards, Henry Tate and Andrew Carnegie, helped to increase the number of public libraries from the late 19th century. Carnegie alone built over 2000 libraries in the US, 660 Carnegie Libraries in Britain, in addition to many more in the Commonwealth. Carnegie also funded academic libraries, favoring small schools and schools with African American students. “In 1899, Pennsylvania State College became the first college to receive Carnegie funding ($150,000) and their library was constructed in 1903.”

Types

Many institutions make a distinction between a circulating or lending library, where materials are expected and intended to be loaned to patrons, institutions, or other libraries, and a reference library where material is not lent out. Modern libraries are often a mixture of both, containing a general collection for circulation, and a reference collection which is restricted to the library premises. Also, increasingly, digital collections enable broader access to material that may not circulate in print, and enables libraries to expand their collections even without building a larger facility.

Academic libraries

Main article: Academic library

Academic libraries are generally located on college and university campuses and primarily serve the students and faculty of that and other academic institutions. Some academic libraries, especially those at public institutions, are accessible to members of the general public in whole or in part.

Academic libraries are libraries that are hosted in post-secondary educational institutions, such as colleges and universities. Their main function are to provide support in research and resource linkage for students and faculty of the educational institution. Specific course-related resources are usually provided by the library, such as copies of textbooks and article readings held on 'reserve' (meaning that they are loaned out only on a short-term basis, usually a matter of hours).

Academic libraries offer workshops and courses outside of formal, graded coursework, which are meant to provide students with the tools necessary to succeed in their programs. These workshops may include help with citations, effective search techniques, journal databases, and electronic citation software. These workshops provide students with skills that can help them achieve success in their academic careers (and often, in their future occupations), which they may not learn inside the classroom.

The academic library provides a quiet study space for students on campus; it may also provide group study space, such as meeting rooms. In North America, Europe, and other parts of the world, academic libraries are becoming increasingly digitally oriented. The library provides a "gateway" for students and researchers to access various resources, both print/physical and digital. Academic institutions are subscribing to electronic journals databases, providing research and scholarly writing software, and usually provide computer workstations or computer labs for students to access journals, library search databases and portals, institutional electronic resources, Internet access, and course- or task-related software (i.e. word processing and spreadsheet software). They are increasingly acting as an electronic repository for institutional scholarly research and academic knowledge, such as the collection and curation of digital copies of students' theses and dissertations.

Children's libraries

Children's libraries are special collections of books intended for juvenile readers and usually kept in separate rooms of general public libraries. Some children's libraries have entire floors or wings dedicated to them in bigger libraries while smaller ones may have a separate room or area for children. They are an educational agency seeking to acquaint the young with the world's literature and to cultivate a love for reading. Their work supplements that of the public schools.

Services commonly provided by public libraries may include storytelling sessions for infants, toddlers, preschool children, or after-school programs, all with an intention of developing early literacy skills and a love of books. One of the most popular programs offered in public libraries are summer reading programs for children, families, and adults.

Another popular reading program for children is PAWS TO READ or similar programs where children can read to certified therapy dogs. Since animals are a calming influence and there is no judgment, children learn confidence and a love of reading. Many states have these types of programs parents just have to ask their librarian to see if it is available at their local library.

National libraries

A national or state library serves as a national repository of information, and has the right of legal deposit, which is a legal requirement that publishers in the country need to deposit a copy of each publication with the library. Unlike a public library, a national library rarely allows citizens to borrow books. Often, their collections include numerous rare, valuable, or significant works. There are wider definitions of a national library, putting less emphasis on the repository character. The first national libraries had their origins in the royal collections of the sovereign or some other supreme body of the state.

Many national libraries cooperate within the National Libraries Section of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) to discuss their common tasks, define and promote common standards, and carry out projects helping them to fulfil their duties. The national libraries of Europe participate in The European Library which is a service of the Conference of European National Librarians (CENL).

Public lending libraries

Main article: Public library

A public library provides services to the general public. If the library is part of a countywide library system, citizens with an active library card from around that county can use the library branches associated with the library system. A library can serve only their city, however, if they are not a member of the county public library system. Much of the materials located within a public library are available for borrowing. The library staff decides upon the number of items patrons are allowed to borrow, as well as the details of borrowing time allotted. Typically, libraries issue library cards to community members wishing to borrow books. Often visitors to a city are able to obtain a public library card.

Many public libraries also serve as community organizations that provide free services and events to the public, such as reading groups and toddler story time. For many communities, the library is a source of connection to a vast world, obtainable knowledge and understanding, and entertainment. According to a study by the Pennsylvania Library Association, public library services play a major role in fighting rising illiteracy rates among youths. Public libraries are protected and funded by the public they serve.

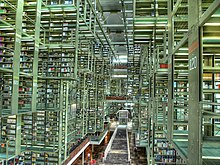

As the number of books in libraries have steadily increased since their inception, the need for compact storage and access with adequate lighting has grown. The stack system involves keeping a library's collection of books in a space separate from the reading room. This arrangement arose in the 19th century. Book stacks quickly evolved into a fairly standard form in which the cast iron and steel frameworks supporting the bookshelves also supported the floors, which often were built of translucent blocks to permit the passage of light (but were not transparent, for reasons of modesty). The introduction of electrical lighting had a huge impact on how the library operated. The use of glass floors was largely discontinued, though floors were still often composed of metal grating to allow air to circulate in multi-story stacks. As more space was needed, a method of moving shelves on tracks (compact shelving) was introduced to cut down on otherwise wasted aisle space.

Library 2.0, a term coined in 2005, is the library's response to the challenge of Google and an attempt to meet the changing needs of users by using web 2.0 technology. Some of the aspects of Library 2.0 include, commenting, tagging, bookmarking, discussions, use of online social networks by libraries, plug-ins, and widgets. Inspired by web 2.0, it is an attempt to make the library a more user-driven institution.

Despite the importance of public libraries, they are routinely having their budgets cut by state legislature. Funding has dwindled so badly that many public libraries have been forced to cut their hours and release employees.

Reference libraries

A reference library does not lend books and other items; instead, they must be read at the library itself. Typically, such libraries are used for research purposes, for example at a university. Some items at reference libraries may be historical and even unique. Many lending libraries contain a "reference section", which holds books, such as dictionaries, which are common reference books, and are therefore not lent out. Such reference sections may be referred to as "reading rooms", which may also include newspapers and periodicals. An example of a reading room is the Hazel H. Ransom Reading Room at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin, which maintains the papers of literary agent Audrey Wood.

Research libraries

A research library is a collection of materials on one or more subjects. A research library supports scholarly or scientific research and will generally include primary as well as secondary sources; it will maintain permanent collections and attempt to provide access to all necessary materials. A research library is most often an academic or national library, but a large special library may have a research library within its special field, and a very few of the largest public libraries also serve as research libraries. A large university library may be considered a research library; and in North America, such libraries may belong to the Association of Research Libraries. In the United Kingdom, they may be members of Research Libraries UK (RLUK).

A research library can be either a reference library, which does not lend its holdings, or a lending library, which does lend all or some of its holdings. Some extremely large or traditional research libraries are entirely reference in this sense, lending none of their materials; most academic research libraries, at least in the US and the UK, now lend books, but not periodicals or other materials. Many research libraries are attached to a parental organization and serve only members of that organization. Examples of research libraries include the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and the New York Public Library Main Branch on 42nd Street in Manhattan, State Public Scientific Technological Library of the Sibirian Branch of the Russian Academy of Science.

Special libraries

Main article: Special library

All other libraries, including digital libraries, fall into the "special library" category. Many private businesses and public organizations, including hospitals, churches, museums, research laboratories, law firms, and many government departments and agencies, maintain their own libraries for the use of their employees in doing specialized research related to their work. Depending on the particular institution, special libraries may or may not be accessible to the general public or elements thereof. In more specialized institutions such as law firms and research laboratories, librarians employed in special libraries are commonly specialists in the institution's field rather than generally trained librarians, and often are not required to have advanced degrees in specifically library-related field due to the specialized content and clientele of the library.

Some special libraries, such as governmental law libraries, hospital libraries, and military base libraries commonly are open to public visitors to the institution in question. Depending on the particular library and the clientele it serves, special libraries may offer services similar to research, reference, public, academic, or children's libraries, often with restrictions such as only lending books to patients at a hospital or restricting the public from parts of a military collection. Given the highly individual nature of special libraries, visitors to a special library are often advised to check what services and restrictions apply at that particular library.

Special libraries are distinguished from special collections, which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and other special materials, though some special libraries have special collections of their own, typically related to the library's specialized subject area.

For more information on specific types of special libraries, see law libraries, medical libraries, music libraries, or transportation libraries.

Organization

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Most libraries have materials arranged in a specified order according to a library classification system, so that items may be located quickly and collections may be browsed efficiently. Some libraries have additional galleries beyond the public ones, where reference materials are stored. These reference stacks may be open to selected members of the public. Others require patrons to submit a "stack request," which is a request for an assistant to retrieve the material from the closed stacks: see List of closed stack libraries (in progress).

Larger libraries are often divided into departments staffed by both paraprofessionals and professional librarians.

- Circulation (or Access Services) – Handles user accounts and the loaning/returning and shelving of materials.

- Collection Development – Orders materials and maintains materials budgets.

- Reference – Staffs a reference desk answering questions from users (using structured reference interviews), instructing users, and developing library programming. Reference may be further broken down by user groups or materials; common collections are children's literature, young adult literature, and genealogy materials.

- Technical Services – Works behind the scenes cataloging and processing new materials and deaccessioning weeded materials.

- Stacks Maintenance – Re-shelves materials that have been returned to the library after patron use and shelves materials that have been processed by Technical Services. Stacks Maintenance also shelf reads the material in the stacks to ensure that it is in the correct library classification order.

Basic tasks in library management include the planning of acquisitions (which materials the library should acquire, by purchase or otherwise), library classification of acquired materials, preservation of materials (especially rare and fragile archival materials such as manuscripts), the deaccessioning of materials, patron borrowing of materials, and developing and administering library computer systems. More long-term issues include the planning of the construction of new libraries or extensions to existing ones, and the development and implementation of outreach services and reading-enhancement services (such as adult literacy and children's programming). Library materials like books, magazines, periodicals, CDs, etc. are managed by Dewey Decimal Classification Theory and modified Dewey Decimal Classification Theory is more practical reliable system for library materials management.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has published several standards regarding the management of libraries through its Technical Committee 46 (TC 46), which is focused on "libraries, documentation and information centers, publishing, archives, records management, museum documentation, indexing and abstracting services, and information science". The following is a partial list of some of them:

- ISO 2789:2006 Information and documentation—International library statistics

- ISO 11620:1998 Information and documentation—Library performance indicators

- ISO 11799:2003 Information and documentation—Document storage requirements for archive and library materials

- ISO 14416:2003 Information and documentation—Requirements for binding of books, periodicals, serials, and other paper documents for archive and library use—Methods and materials

- ISO/TR 20983:2003 Information and documentation—Performance indicators for electronic library services

Buildings

Librarians have sometimes complained that some of the library buildings which have been used to accommodate libraries have been inadequate for the demands made upon them. In general, this condition may have resulted from one or more of the following causes:

- an effort to erect a monumental building; most of those who commission library buildings are not librarians and their priorities may be different

- to conform it to a type of architecture unsuited to library purposes

- the appointment, often by competition, of an architect unschooled in the requirements of a library

- failure to consult with the librarian or with library experts

Much advancement has undoubtedly been made toward cooperation between architect and librarian, and many good designers have made library buildings their speciality, nevertheless it seems that the ideal type of library is not yet realized—the type so adapted to its purpose that it would be immediately recognized as such, as is the case with school buildings at the present time. This does not mean that library constructions should conform rigidly to a fixed standard of appearance and arrangement, but it does mean that the exterior should express as nearly as possible the purpose and functions of the interior.

Usage

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Patrons may not know how to fully use the library's resources. This can be due to some individuals' unease in approaching a staff member. Ways in which a library's content is displayed or accessed may have the most impact on use. An antiquated or clumsy search system, or staff unwilling or untrained to engage their patrons, will limit a library's usefulness. In the public libraries of the United States, beginning in the 19th century, these problems drove the emergence of the library instruction movement, which advocated library user education. One of the early leaders was John Cotton Dana. The basic form of library instruction is sometimes known as information literacy.

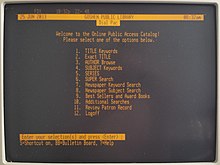

Libraries should inform their users of what materials are available in their collections and how to access that information. Before the computer age, this was accomplished by the card catalogue—a cabinet (or multiple cabinets) containing many drawers filled with index cards that identified books and other materials. In a large library, the card catalogue often filled a large room. The emergence of the Internet, however, has led to the adoption of electronic catalogue databases (often referred to as "webcats" or as online public access catalogues, OPACs), which allow users to search the library's holdings from any location with Internet access. This style of catalogue maintenance is compatible with new types of libraries, such as digital libraries and distributed libraries, as well as older libraries that have been retrofitted. Electronic catalogue databases are criticized by some who believe that the old card catalogue system was both easier to navigate and allowed retention of information, by writing directly on the cards, that is lost in the electronic systems. This argument is analogous to the debate over paper books and e-books. While libraries have been accused of precipitously throwing out valuable information in card catalogues, most modern ones have nonetheless made the move to electronic catalogue databases. Large libraries may be scattered within multiple buildings across a town, each having multiple floors, with multiple rooms housing the resources across a series of shelves. Once a user has located a resource within the catalogue, they must then use navigational guidance to retrieve the resource physically; a process that may be assisted through signage, maps, GPS systems, or RFID tagging.

Finland has the highest number of registered book borrowers per capita in the world. Over half of Finland's population are registered borrowers. In the US, public library users have borrowed on average roughly 15 books per user per year from 1856 to 1978. From 1978 to 2004, book circulation per user declined approximately 50%. The growth of audiovisuals circulation, estimated at 25% of total circulation in 2004, accounts for about half of this decline.

Shift to digital libraries

See also: Digital library

In the 21st century, there has been increasing use of the Internet to gather and retrieve data. The shift to digital libraries has greatly impacted the way people use physical libraries. Between 2002 and 2004, the average American academic library saw the overall number of transactions decline approximately 2.2%. Libraries are trying to keep up with the digital world and the new generation of students that are used to having information just one click away. For example, the University of California Library System saw a 54% decline in circulation between 1991 and 2001 of 8,377,000 books to 3,832,000.

These facts might be a consequence of the increased availability of e-resources. In 1999–2000, 105 ARL university libraries spent almost $100 million on electronic resources, which is an increase of nearly $23 million from the previous year. A 2003 report by the Open E-book Forum found that close to a million e-books had been sold in 2002, generating nearly $8 million in revenue. Another example of the shift to digital libraries can be seen in Cushing Academy’s decision to dispense with its library of printed books—more than 20,000 volumes in all—and switch over entirely to digital media resources.

One claim to why there is a decrease in the usage of libraries stems from the observation of the research habits of undergraduate students enrolled in colleges and universities. There have been claims that college undergraduates have become more used to retrieving information from the Internet than a traditional library. As each generation becomes more in tune with the Internet, their desire to retrieve information as quickly and easily as possible has increased. Finding information by simply searching the Internet could be much easier and faster than reading an entire book. In a survey conducted by NetLibrary, 93% of undergraduate students claimed that finding information online makes more sense to them than going to the library. Also, 75% of students surveyed claimed that they did not have enough time to go to the library and that they liked the convenience of the Internet. While the retrieving information from the Internet may be efficient and time saving than visiting a traditional library, research has shown that undergraduates are most likely searching only .03% of the entire web. The information that they are finding might be easy to retrieve and more readily available, but may not be as in depth as information from other resources such as the books available at a physical library.

In the mid-2000s, Swedish company Distec invented a library book vending machine known as the GoLibrary, that offers library books to people where there is no branch, limited hours, or high traffic locations such as El Cerrito del Norte BART station in California.

The Internet

A library may make use of the Internet in a number of ways, from creating their own library website to making the contents of its catalogues searchable online. Some specialised search engines such as Google Scholar offer a way to facilitate searching for academic resources such as journal articles and research papers. The Online Computer Library Center allows anyone to search the world's largest repository of library records through its WorldCat online database. Websites such as LibraryThing and Amazon provide abstracts, reviews, and recommendations of books. Libraries provide computers and Internet access to allow people to search for information online. Online information access is particularly attractive to younger library users.

Digitization of books, particularly those that are out-of-print, in projects such as Google Books provides resources for library and other online users. Due to their holdings of valuable material, some libraries are important partners for search engines such as Google in realizing the potential of such projects and have received reciprocal benefits in cases where they have negotiated effectively. As the prominence of and reliance on the Internet has grown, library services have moved the emphasis from mainly providing print resources to providing more computers and more Internet access. Libraries face a number of challenges in adapting to new ways of information seeking that may stress convenience over quality, reducing the priority of information literacy skills. The potential decline in library usage, particularly reference services, puts the necessity for these services in doubt.

Library scholars have acknowledged that libraries need to address the ways that they market their services if they are to compete with the Internet and mitigate the risk of losing users. This includes promoting the information literacy skills training considered vital across the library profession. However, marketing of services has to be adequately supported financially in order to be successful. This can be problematic for library services that are publicly funded and find it difficult to justify diverting tight funds to apparently peripheral areas such as branding and marketing.

The privacy aspect of library usage in the Internet age is a matter of growing concern and advocacy; privacy workshops are run by the Library Freedom Project which teach librarians about digital tools (such as the Tor Project) to thwart mass surveillance.

Associations

See also: List of library associationsThe International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) is the leading international association of library organisations. It is the global voice of the library and information profession, and its annual conference provides a venue for librarians to learn from one another.

Library associations in Asia include the Indian Library Association (ILA), Indian Association of Special Libraries and Information Centers (IASLIC), Bengal Library Association (BLA), Kolkata, Pakistan Library Association, the Pakistan Librarians Welfare Organization, the Bangladesh Association of Librarians, Information Scientists and Documentalists, the Library Association of Bangladesh, and the Sri Lanka Library Association (founded 1960).

National associations of the English-speaking world include the American Library Association, the Australian Library and Information Association, the Canadian Library Association, the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa, and the Research Libraries UK (a consortium of 30 university and other research libraries in the United Kingdom). Library bodies such as CILIP (formerly the Library Association, founded 1877) may advocate the role that libraries and librarians can play in a modern Internet environment, and in the teaching of information literacy skills.

Public library advocacy is support given to a public library for its financial and philosophical goals or needs. Most often this takes the form of monetary or material donations or campaigning to the institutions which oversee the library, sometimes by advocacy groups such as Friends of Libraries and community members. Originally, library advocacy was centered on the library itself, but current trends show libraries positioning themselves to demonstrate they provide "economic value to the community" in means that are not directly related to the checking out of books and other media.

See also

2Lists of libraries

Main articles: List of libraries, List of national and state libraries, and List of libraries in the ancient worldReferences

- "Library - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". merriam-webster.com.

- "Library ... collection of books, public or private; room or building where these are kept; similar collection of films, records, computer routines, etc. or place where they are kept; series of books issued in similar bindings as set."--Allen, R. E., ed. (1984) The Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 421

- Casson, Lionel (11 August 2002). Libraries in the Ancient World. Yale University Press. p. 3. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ Krasner-Khait, Barbara (2010). "History Magazine". history-magazine.com. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Maclay, Kathleen (6 May 2003). "Clay cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia to be placed online". Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Renfrew, Colin. Prehistory The Making Of The Human Mind, New York: Modern Library, 2008.

- Roberts, John Morris (17 July 1997). A short history of the world. Oxford University Press. p. 35. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- The American International Encyclopedia, New York: J. J. Little & Ives, 1954; Volume IX

- ""Assurbanipal Library Phase 1", British Museum One". Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Epic of Creation", in Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford, 1989; pp. 233-81

- "Epic of Gilgamesh", in Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford, 1989; pp. 50–135

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2007: pg. 263

- ^ Mukherjee, A. K. Librarianship: Its Philosophy and History. Asia Publishing House (1966) p. 86

- Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, Sagan, C 1980, "Episode 1: The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean"

- ^ Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010

- Swain, Simon (2002). Dio Chrysostom: Politics, Letters, and Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780199255214.

Nevertheless, in 92 the same office went to a Greek, Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, who belonged to a family of priests of Rome hailing from Sardis; entering the Senate under Vespasian, he was subsequently to be appointed proconsul of Asia under Trajan, possibly in 105/6. Celsus' son, Aquila, was also to be made suffectus in 110, although he is certainly remembered more as the builder of the famous library his father envisioned for Ephesus.

- Nicols, John (1978). Vespasian and the partes Flavianae. Steiner. p. 109. ISBN 9783515023931.

Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (PIR2 J 260) was a romanized Greek of Ephesus or Sardes who became the first eastern consul.

- Seneca, De tranquillitate animi ix.4–7.

- Casson, L. (2001). Libraries in the ancient world. New Haven: Yale University Press; Ewald, L. A. (2004). Library Culture in Ancient Rome, 100 B.C. – A.D. 400. Kentucky Libraries, 68(1), 9-11;Buchanan, S. (2012). Designing the Research Commons: Classical Models for School Libraries. School Libraries Worldwide, 18(1), 56-69.

- Ewald, 2004, p.9

- Casson, 2001, p. 80

- Casson, 2001, p. 81; Buchanan, 2012, p. 61

- Casson, 2001, p.84; Buchanan, 2012, pp. 61-62

- Ewald, 2004, p.10; Buchanan, 2012, p.62;Casson, p.61

- Houston, G. W. (2008). Tiberius and the Libraries: Public Book Collections and Library Buildings in the Early Roman Empire. Libraries & the Cultural Record, 43, 247-269.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet Thelma (1995). China bibliography: a research guide ... – Google Books. ISBN 978-90-04-10278-1. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Stradavinisaporifc.it". Stradavinisaporifc.it. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- Bischoff, B. and Gorman, M. (1994). Manuscripts and libraries in the age of Charlemagne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Staikos, K. K. (2004). The history of the library in Western civilization. New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press, p.12

- Staikos, 2007, p.8

- Murray, 2009, p.24

- Papademetriou, G. C. (2000). "The Patriarchal libraries of Constantinople". Greek Orthodox Theological Review. 45 (1–4): 171–190.

- Lyons, M. (2011). Books: A living history. London: Thames and Hudson, pp.35-36.

- Murray, 2009, p. 50

- Peterson, H. A. (2010). The genesis of monastic libraries. Libraries & the Cultural Record, 45(3), 320-332, p. 320.

- Murray, 2009; Peterson, 2010.

- Murray, 2009, pp. 36, -38

- Murray, 2009, p.36

- Peterson, 2010, p.329

- Peterson, 2010, pp. 330-331

- Thompson, J.W. (1957). The medieval library. New York: Hafner Publishing Co., p. 311.

- ^ Thompson, 1957, p. 312

- Staikos, 2007, pp. 30-31

- Stoikos, 2007, p. 33

- Staikos, 2007, pp. 32-33

- Thompson, 1957, pp. 312-313

- Thompson, 1957, p. 313

- Hillerbrand, Hans J. (2006). "On Book Burnings and Book Burners: Reflections on the Power (and Powerlessness) of Ideas". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 74 (3): 593–614. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfj117.

- Staikos, 2007, p. 43

- Staikos, 2007, p. 44

- Staikos, 2007, p. 44-45

- Staikos, 2007, p.429

- Thompson, 1957, pp.313-314

- Murray, S. (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York, NY : Skyhorse Pub. ; Chicago : ALA Editions, 2009. pg.57

- Goeje, M. J. de, ed. (1906). "Al-Muqaddasi: Ahsan al-Taqasim". Bibliotheca geographorum Arabicorum (in Arabic). Vol. III. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 449.