| Revision as of 20:57, 28 June 2017 edit86.152.131.125 (talk) →Works← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:37, 4 July 2017 edit undoInternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers5,383,816 edits Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.4)Next edit → | ||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

| ===Development of Hindavi=== | ===Development of Hindavi=== | ||

| Khusrow wrote primarily in ]. Many ] (historically known as Hindavi) verses are attributed to him, although there is no evidence for their composition by Khusrow before the 18th century.<ref></ref><ref>Khusrau's Hindvi Poetry, An Academic Riddle? Yousuf Saeed, 2003</ref> The language of the Hindustani verses appear to be relatively modern. He also wrote a war ballad in ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tariq|first=Rahman|title=Punjabi Language during British Rule|journal=JPS|volume=14|issue=1|url=http://www.global.ucsb.edu/punjab/14.1_Rahman.pdf}}</ref> In addition, he spoke ] and ].<ref name="Bashiri"/><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref> His poetry is still sung today at ] shrines throughout ] and ]. | Khusrow wrote primarily in ]. Many ] (historically known as Hindavi) verses are attributed to him, although there is no evidence for their composition by Khusrow before the 18th century.<ref></ref><ref>Khusrau's Hindvi Poetry, An Academic Riddle? Yousuf Saeed, 2003</ref> The language of the Hindustani verses appear to be relatively modern. He also wrote a war ballad in ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tariq |first=Rahman |title=Punjabi Language during British Rule |journal=JPS |volume=14 |issue=1 |url=http://www.global.ucsb.edu/punjab/14.1_Rahman.pdf |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120915130644/http://www.global.ucsb.edu/punjab/14.1_Rahman.pdf |archivedate=15 September 2012 }}</ref> In addition, he spoke ] and ].<ref name="Bashiri"/><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref> His poetry is still sung today at ] shrines throughout ] and ]. | ||

| ===Dastangoi=== | ===Dastangoi=== | ||

Revision as of 01:37, 4 July 2017

| Amir Khusrau | |

|---|---|

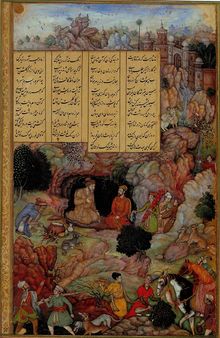

Amir Khusrow teaching his disciples in a miniature from a manuscript of Majlis al-Ushshaq by Husayn Bayqarah. Amir Khusrow teaching his disciples in a miniature from a manuscript of Majlis al-Ushshaq by Husayn Bayqarah. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ab'ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn K͟husrau |

| Born | 1253 Patiyali, Delhi Sultanate |

| Died | October 1325 Delhi, Delhi Sultanate |

| Genres | Ghazal, Khayal, Qawwali, Ruba'i, Tarana |

| Occupation(s) | Sufi, musician, poet, composer, author, scholar |

| Website | http://www.khusrau.com |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

| Ideas |

| Practices |

Sufi orders

|

| List of sufis |

| Topics in Sufism |

|

|

Ab'ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253 – 1325) (Template:Lang-ur, Hindi:अमीर ख़ुसरो), better known as Amīr Khusrow, was a Sufi musician, poet and scholar. He was an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian subcontinent. He was a mystic and a spiritual disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi, and is reputed to have invented certain musical instruments like the sitar and tabla. He wrote poetry primarily in Persian, but also in Hindavi. A vocabulary in verse, the Ḳhāliq Bārī, containing Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi terms is often attributed to him. Khusrow is sometimes referred to as the "parrot of India".

Khusrow is regarded as the "father of qawwali" (a devotional music form of the Sufis in the Indian subcontinent), and introduced the ghazal style of song into India, both of which still exist widely in India and Pakistan. He is also credited with introducing Persian, Arabic and Turkish elements into Indian classical music and was the originator of the khayal and tarana styles of music.

Khusrow was an expert in many styles of Persian poetry which were developed in medieval Persia, from Khāqānī's qasidas to Nizami's khamsa. He used 11 metrical schemes with 35 distinct divisions. He wrote in many verse forms including ghazal, masnavi, qata, rubai, do-baiti and tarkib-band. His contribution to the development of the ghazal was significant.

Early life and background

Amīr Khusrow was born in Patiyali in the Delhi Sultanate (in modern day Uttar Pradesh, India) in 1253. His father, Amīr Saif ud-Dīn Mahmūd, was a Turkic officer and a member of the Lachin tribe of Transoxania, themselves belonging to the Kara-Khitais. During Genghis Khan's invasion of Central Asia, Amir Saif ud-Din migrated from his hometown of Kesh, near Samarkand, to Balkh, where he was the chieftain of the Hazara. Shams ud-Din Iltutmish, the Sultan of Delhi at the time, welcomed them to the Delhi Sultanate. Iltutmish provided shelter to exiled princes, artisans, scholars and rich nobles. In 1230, Amir Saif ud-Din was granted a fief in the district of Patiyali.

Amir Saif ud-Din married Bibi Daulatnaz, the daughter of Rawat Arz, who was the famous war minister of Ghiyas ud-Din Balban, the ninth Sultan of Delhi. Daulatnaz's family belonged to the Rajput tribes of modern day Uttar Pradesh. Amir Saif ud-Din and Bibi Daulatnaz had four children: three sons (one of whom was Khusrow) and a daughter. Amir Saif ud-Din Mahmud died in 1260.

Khusrow was an intelligent child. He started learning and writing poetry at the age of eight. After the death of his father in 1260, his mother brought him up and traveled with him to Delhi to his maternal grandfather Imadul Mulk's house. His first divan, Tuhfat us-Sighr (The Gift of Childhood), containing poems composed between the ages of 16 and 18, was compiled in 1271. In 1273, when Khusrow was 20 years old, his grandfather, who was reportedly 113 years old, died.

Career

After Khusrow's grandfather's death, Khusrow joined the army of Malik Chajju, a nephew of the reigning Sultan, Ghiyas ud-Din Balban. This brought his poetry to the attention of the Assembly of the Royal Court where he was honored.

Nasir ud-Din Bughra Khan, the second son of Balban, was invited to listen to Khusrow. He was impressed and became Khusrow's patron in 1276. In 1277 Bughra Khan was then appointed ruler of Bengal, and Khusrow visited him in 1279 while writing his second divan, Wast ul-Hayat (The Middle of Life). Khusrow then returned to Delhi. Balban's eldest son, Khan Muhammad (who was in Multan), arrived in Delhi, and when he heard about Khusrow he invited him to his court. Khusrow then accompanied him to Multan in 1281. Multan at the time was the gateway to India and was a center of knowledge and learning. Caravans of scholars, tradesmen and emissaries transited through Multan from Baghdad, Arabia and Persia on their way to Delhi. Khusrow wrote that:

I tied the belt of service on my waist and put on the cap of companionship for another five years. I imparted lustre to the water of Multan from the ocean of my wits and pleasantries.

On 9 March 1285, Khan Muhammad was killed in battle while fighting Mongols who were invading the Sultanate. Khusrow wrote two elegies in grief of his death. Khusrow also participated as a soldier in battles with invading Mongols in which he was taken prisoner, but later escaped. In 1287, Khusrow travelled to Awadh with another of his patrons, Amir Ali Hatim. At the age of eighty, Balban called his second son Bughra Khan back from Bengal, but Bughra Khan refused. After Balban's death in 1287, his grandson Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad, Bughra Khan's son, was made the Sultan of Delhi at the age of 17. Khusrow remained in Qaiqabad's service for two years, from 1287 to 1288. In 1288 Khusrow finished his first masnavi, Qiran us-Sa'dain (Meeting of the Two Auspicious Stars), which was about Bughra Khan meeting his son Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad after a long enmity. After Qaiqabad suffered a stroke in 1290, nobles appointed his three year old son Shams ud-Din Kayumars as Sultan. A Turk named Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khilji then marched on Delhi, killed Qaiqabad and became Sultan, thus ending the Mamluk dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate and starting the Khilji dynasty.

Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khilji appreciated poetry and invited many poets to his court. Khusrow was honoured and respected in his court and was given the title "Amir". He was given the job of "Mushaf-dar". Court life made Khusrow focus more on his literary works. Khusrow's ghazals which he composed in quick succession were set to music and were sung by singing girls every night before the Sultan. Khusrow writes about Jalal ud-Din Firuz:

The King of the world Jalal ud-Din, in reward for my infinite pain which I undertook in composing verses, bestowed upon me an unimaginable treasure of wealth.

In 1290 Khusrow completed his second masnavi, Miftah ul-Futuh (Key to the Victories), in praise of Jalal ud-Din Firuz's victories. In 1294 Khusrow completed his third divan, Ghurrat ul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection), which consisted of poems composed between the ages of 34 and 41.

After Jalal ud-Din Firuz, Ala ud-Din Khilji ascended to the throne of Delhi in 1296. Khusrow wrote the Khaza'in ul-Futuh (The Treasures of Victory) recording Ala ud-Din's construction works, wars and administrative services. He then composed a khamsa (quintet) with five masnavis, known as Khamsa-e-Khusrow (Khamsa of Khusrow), completing it in 1298. The khamsa emulated that of the earlier poet of Persian epics, Nizami Ganjavi. The first masnavi in the khamsa was Matla ul-Anwar (Rising Place of Lights) consisting of 3310 verses (completed in 15 days) with ethical and Sufi themes. The second masnavi, Khusrow-Shirin, consisted of 4000 verses. The third masnavi, Laila-Majnun, was a romance. The fourth voluminous masnavi was Aina-e-Sikandari, which narrated the heroic deeds of Alexander the Great in 4500 verses. The fifth masnavi was Hasht-Bihisht, which was based on legends about Bahram V, the fifteenth king of the Sasanian Empire. All these works made Khusrow a leading luminary in the world of poetry. Ala ud-Din Khilji was highly pleased with his work and rewarded him handsomely. When Ala ud-Din's son and future successor Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khilji was born, Khusrow prepared the horoscope of Mubarak Shah Khilji in which certain predictions were made. This horoscope is included in the masnavi Saqiana.

In 1300, when Khusrow was forty seven years old, his mother and brother died. He wrote these lines in their honour:

A double radiance left my star this year

Gone are my brother and my mother,

My two full moons have set and ceased to shine

In one short week through this ill-luck of mine.

Khusrow's homage to his mother on her death was:

Where ever the dust of your feet is found is like a relic of paradise for me.

In 1310 Khusrow became close to a Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, Nizamuddin Auliya. In 1315, Khusrow completed the romantic masnavi Duval Rani - Khizr Khan (Duval Rani and Khizr Khan), about the marriage of the Vaghela princess Duval Rani to Khizr Khan, one of Ala ud-Din Khilji's sons.

After Ala ud-Din Khilji's death in 1316, his son Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khilji became the Sultan of Delhi. Khusrow wrote a masnavi on Mubarak Shah Khilji called Nuh Sipihr (Nine Skies), which described the events of Mubarak Shah Khilji's reign. He classified his poetry in nine chapters, each part of which is considered a "sky". In the third chapter he wrote a vivid account of India and its environment, seasons, flora and fauna, cultures, scholars, etc. He wrote another book during Mubarak Shah Khilji's reign by name of Ijaz-e-Khusravi (The Miracles of Khusrow), which consisted of five volumes. In 1317 Khusrow compiled Baqia-Naqia (Remnants of Purity). In 1319 he wrote Afzal ul-Fawaid (Greatest of Blessings), a work of prose that contained the teachings of Nizamuddin Auliya.

In 1320 Mubarak Shah Khilji was killed by Khusro Khan, who thus ended the Khilji dynasty and briefly became Sultan of Delhi. Within the same year, Khusro Khan was captured and beheaded by Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq, who became Sultan and thus began the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1321 Khusrow began to write a historic masnavi named Tughlaq Nama (Book of the Tughlaqs) about the reign of Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq and that of other Tughlaq rulers.

Khusrow died in October 1325, six months after the death of Nizamuddin Auliya. Khusrow's tomb is next to that of his spiritual master in the Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi. Nihayat ul-Kamaal (The Zenith of Perfection) was compiled probably a few weeks before his death.

Legacy

Amir Khusrow was a prolific classical poet associated with the royal courts of more than seven rulers of the Delhi Sultanate. He wrote many playful riddles, songs and legends which have become a part of popular culture in South Asia. His riddles are one of the most popular forms of Hindavi poetry today. It is a genre that involves double entendre or wordplay. Innumerable riddles by the poet have been passed through oral tradition over the last seven centuries. Through his literary output, Khusrow represents one of the first recorded Indian personages with a true multicultural or pluralistic identity.

Development of Hindavi

Khusrow wrote primarily in Persian. Many Hindustani (historically known as Hindavi) verses are attributed to him, although there is no evidence for their composition by Khusrow before the 18th century. The language of the Hindustani verses appear to be relatively modern. He also wrote a war ballad in Punjabi. In addition, he spoke Arabic and Sanskrit. His poetry is still sung today at Sufi shrines throughout Pakistan and India.

Dastangoi

Dastangoi is an oral art of storytelling developed by Amir Khusrow. Legend has it that Khusrow's master, the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya, had fallen ill. To cheer him up, Khusrow started telling him a series of dastans in the style of One Thousand and One Nights, one of the most notable of which was Qissa Chahar Dervesh (The Tale of the Four Dervishes). Once Khusrow had finished telling his stories, Nizamuddin Auliya had recovered, and prayed that anyone who listened to these stories would also be cured.

Contributions to music

Khusrow is loosely credited for the invention of the tabla, a musical instrument popular in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. The term "tabla" is derived from the Arabic word "tabl", which means "drum". However, there is no proof that tabla, as well as the sitar, were invented by Amir Khusrow. For example, none of these instruments appear on the visual arts (illustrated manuscripts and royal paintings) before the 18th century, unlike other instruments.

The development of the tabla originated from the need to have a drum that could be played from the top in the sitting position to enable more complex rhythm structures that were required for the new Indian Sufi vocal style of singing/chanting and zikr and to complement the complex early sitar melodies that Khusrow was composing. The tabla uses a complex finger tip and hand percussive technique played from the top, unlike the pakhawaj (an old dholak-like instrument) and the mridangam which mainly use the full palm, are sideways in motion and are more limited in terms of sound complexity.

700th Birth Anniversary

In 1976 the renowned Pakistani musician Khurshid Anwar played a key role in observing the 700th birth anniversary of Amir Khusrow. Since he was also a musicologist, he wrote one of his rare music articles on Amir Khusrow, "A gift to posterity". In addition, he actively planned music events and activities throughout 1976. In Pakistan, Anwar had also been praised for his efforts to keep alive classical music not only through his many film compositions in Pakistan, but also through his unique collection of classical music performances recorded by EMI Pakistan, known as Aahang-e-Khusravi in two parts in 1978. The second part of the Aahang-e-Khusravi recordings was known as Gharanon Ki Gaiyki which consisted of audio recordings of representatives of the main gharanas of classical singers in Pakistan on 20 audio cassettes. All this was meant to be a tribute to Amir Khusrow.

Shalimar Bagh Mughal Inscription

Inscribed in the top terrace of the Shalimar Bagh, Srinagar (now in Jammu and Kashmir, India), are some famous phrases in Persian, which are sometimes attributed to Khusrow, although are not found in any of his written works:

Agar Firdaus bar ru-ye zamin ast,

Hamin ast o hamin ast o hamin ast.

In English: "If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this." This verse is also found on several Mughal structures, supposedly in reference to Kashmir.

Works

- Tuhfat us-Sighr (The Gift of Childhood), 1271 - Khusrow's first divan, contains poems composed between the ages of 16 and 18.

- Wast ul-Hayat (The Middle of Life), 1279 - Khusrow's second divan.

- Qiran us-Sa’dain (Meeting of the Two Auspicious Stars), 1289 - Khusrow's first masnavi, which detailed the historic meeting of Bughra Khan and his son Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad after a long enmity.

- Miftah ul-Futuh (Key to the Victories), 1290 - Khusrow's second masnavi, in praise of the victories of Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khilji.

- Ghurrat ul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection), 1294 - poems composed by Khusrow between the ages of 34 and 41.

- Khaza'in ul-Futuh (The Treasures of Victories), 1296 - details of Ala ud-Din Khilji's construction works, wars, and administrative services.

- Khamsa-e-Khusrow (Khamsa of Khusrow), 1298 - a quintet (khamsa) of five masnavis: Matla ul-Anwar, Khusrow-Shirin, Laila-Majnun, Aina-e-Sikandari and Hasht-Bihisht.

- Saqiana - masnavi containing the horoscope of Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khilji.

- Duval Rani - Khizr Khan (Duval Rani and Khizr Khan), 1316 - a tragedy about the marraige of princess Duval Rani to Ala ud-Din Khilji's son Khizr Khan.

- Nuh Sipihr (Nine Skies), 1318 - Khusrow's masnavi on the reign of Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khilji, which includes vivid perceptions of India and its culture.

- Ijaz-e-Khusravi (The Miracles of Khusrow) - an assortment of prose consisting of five volumes.

- Baqia-Naqia (Remnants of Purity), 1317 - compiled by Khusrow at the age of 64.

- Afzal ul-Fawaid (Greatest of Blessings), 1319 - a work of prose containing the teachings of Nizamuddin Auliya.

- Tughlaq Nama (Book of the Tughlaqs), 1320 - a historic masnavi of the reign of the Tughlaq dynasty.

- Nihayat ul-Kamaal (The Zenith of Perfection), 1325 - compiled by Khusrow probably a few weeks before his death.

- Qissa Chahar Dervesh (The Tale of the Four Dervishes) - a dastan told by Khusrow to Nizamuddin Auliya, resulting in Auliya becoming cured from his illness.

- Ḳhāliq Bārī - a versified glossary of Persian, Arabic, and Hindavi words and phrases often attributed to Amir Khusrow. Hafiz Mehmood Khan Shirani argued that it was completed in 1622 in Gwalior by Ẓiyā ud-Dīn Ḳhusrau.

- Jawahir-e-Khusravi - a divan often dubbed as Khusrow's Hindavi divan.

See also

References

- Rashid, Omar (23 July 2012). "Chasing Khusro". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- Latif, Syed Abdulla (1979) . An Outline of the Cultural History of India. Institute of Indo-Middle East Cultural Studies (reprinted by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers). p. 334. ISBN 81-7069-085-4.

- Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, Harold S. Powers. Sufi Music of India. Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 109, No. 4 (Oct. – Dec. 1989), pp. 702–705. doi:10.2307/604123.

- ^ Schimmel, A. "Amīr Ḵosrow Dehlavī". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Eisenbrauns Inc. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Амир Хосров Дехлеви", Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Moscow, 1970 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dr. Iraj Bashiri. "Amir Khusrau Dihlavi". 2001

- Islamic Culture, by the Islamic Cultural Board, Muhammad Asad, Academic and Cultural Publications Charitable Trust (Hyderabad, India), Marmaduke William Pickthall, 1927, p. 219

- http://www.hazratmehboob-e-elahi.org/chapter-IV-1.htm#a

- Nizamuddin Auliya

- Delhi Sultanate

- ^ Sharma, Sunil (2005). Amir Khusraw : the poet of Sufis and sultans. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 79. ISBN 1851683623.

- In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau, Paul E Losensky, Penguin UK, 2013

- Khusrau's Hindvi Poetry, An Academic Riddle? Yousuf Saeed, 2003

- Tariq, Rahman. "Punjabi Language during British Rule" (PDF). JPS. 14 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Mohammad Habib. Hazrat Amir Khusrau of Delhi, 1979, p. 4

- Islamic Cultural Board. Islamic Culture, 1927, p. 219

- Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume, by Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, 1975, p. 98

- Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume, by Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, 1975, p. 1

- G. N. Devy. Indian Literary Criticism: Theory and Interpretation, Orient Longman, Published 2002

- Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume, by Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, 1975, p. 1

- Encyclopædia Britannica http://www.britannica.com

- Richard Emmert; Yuki Minegishi (1980). Musical voices of Asia: report of (Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1978). Heibonsha. p. 266. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Sitar#World music influence

- http://films.hindi-movies-songs.com/k-anwar.html, Pakistani musician Khurshid Anwar's tribute to Amir Khusrow in 1976 on his 700th Birth Anniversary, Retrieved 18 Jan 2017

- Rajan, Anjana (29 April 2011). "Window to Persia". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- http://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/zubin-mehta-s-concert-mesmerises-kashmir-113090700518_1.html

- "Zubin Mehta's concert mesmerizes Kashmir - The Times of India". The Times Of India.

- Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India 1639-1739, Volume 49 of Cambridge South Asian Studies, Stephen P. Blake, Cambridge University Press, 2002 pp. 44

- Shīrānī, Ḥāfiż Mahmūd. "Dībācha-ye duvum ." In Ḥifż ’al-Lisān (a.k.a. Ḳhāliq Bārī), edited by Ḥāfiż Mahmūd Shīrānī. Delhi: Anjumman-e Taraqqi-e Urdū, 1944.

Further reading

- E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing). 1998. ISBN 0-7007-0406-X

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. ASIN B-000-6BXVT-K

- R.M. Chopra, "The Rise, Growth And Decline of Indo-Persian Literature", Iran Culture House New Delhi and Iran Society, Kolkata, 2nd Ed. 2013.

- Sunil Sharma, Amir Khusraw: Poets of Sultans and Sufis. Oxford: Oneworld Press, 2005.

- Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma, In the Bazaar of Love: Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. New Delhi: Penguin, 2011.

- R.M. Chopra, "Great Poets of Classical Persian", Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, 2014, ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5

Further reading

- Important Works of Amir Khusrau (Complete)

- The Khaza'inul Futuh (Treasures of Victory) of Hazarat Amir Khusrau of Delhi English Translation by Muhammad Habib (AMU). 1931.

- Poems of Amir Khusrau The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, by Sir H. M. Elliot. Vol III. 1866-177. page 523-566.

- Táríkh-i 'Aláí; or, Khazáínu-l Futúh, of Amír Khusrú The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, by Sir H. M. Elliot. Vol III. 1866-177. Page:67-92.

- For greater details refer to "Great Poets of Classical Persian" by R. M. Chopra, Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, 2014, (ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5)

External links

- Works by Amir Khusraw Dihlavi at Project Gutenberg

- Sufism

- Original Persian poems of Amir Khusrow at WikiDorj, free library of Persian poetry

- Use dmy dates from March 2013

- 1253 births

- 1325 deaths

- 13th-century Indian poets

- 14th-century Indian poets

- Chishti Order

- Delhi Sultanate

- Hindi poets

- Indian male poets

- Indian Sufis

- Macaronic language

- Muslim poets

- People from Etah district

- People on postage stamps

- Performers of Sufi music

- Persian-language poets

- Poets from Uttar Pradesh

- Sufi poets

- Urdu poets from India

- Urdu writers from Mughal India