| Revision as of 00:58, 25 October 2006 view source71.202.38.106 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:59, 25 October 2006 view source 71.202.38.106 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| :''This article is about the ] ] philosophy. For other uses (including political parties associated with libertarianism) see ]. | |||

| '''Democracy''' (literally "rule by the people", from the Greek δῆμος ''demos'', "people," and κράτος ''kratos'', "rule") is a ] for a nation state, or for an organization in which all the citizens have a voice in shaping policy. Today democracy is often assumed to be ], but there are many other varieties and the methods used to govern differ. While the term democracy is often used in the context of a political ], the principles are also applicable to other bodies, such as universities, labor unions, public companies, or civic organizations. | |||

| {{Forms of government}} | |||

| ==Varieties== | |||

| {{Libertarianism}} | |||

| {{Democracy}} | |||

| {{Main|Democracy (varieties)}} | |||

| The definition of democracy is made complex by the varied concepts used at different periods of history in different contexts. Political systems, or proposed political systems, claiming or claimed to be democratic have ranged very broadly. For example: | |||

| *] contrasted rule by the many (democracy/]), with rule by the few (]/]), and with rule by a single person (]/] or today ]). He also thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system.. | |||

| *]/] have formed the basis of systems randomly selecting officers from the population: For example, Aristotle described the law courts in Athens which were selected by lot as democratic<ref>Aristotle, Politics 2.1273b</ref> and described elections as oligarchic.<ref>Aristotle, Politics 4.1294b</ref> | |||

| *Certain tribes organised themselves using forms of participatory democracy. | |||

| *Democracy is used to describe systems seeking ] (see ]). | |||

| *Many socialists have argued that socialism necessarily implies democracy (see ]). For this reason Socialist governments of the Communist East block often called themselves democratic. This use of democratic is however strongly disputed because most of these governments were De facto dictatorships kept in power by "sham" elections {{fact}} (for example, the former ]). | |||

| Main varieties include: | |||

| '''Libertarianism''' is a ] advocating that individuals should be free to do whatever they wish with their ] or ], as long as they do not infringe on the same liberty of others. There are two types of libertarians. One type hold as a fundamental maxim that all human interaction should be voluntary and consensual. They maintain that the initiation of force against another ] or his ], with "force" meaning the use of physical force, the threat of it, or the commission of ] against someone who has not initiated physical force, threat, or fraud, is a violation of that principle (many of these are ] or ]). The other type comes from a consequentialist or utilitarian standpoint. Instead of having moral prohibitions against initiation of force, these support a limited government that engages in the minimum amount of initiatory force (such as levying taxes to provide some public goods such as defense and roads, as well as some minimal regulation), because they believe it to be necessary to ensure maximum individual freedom (these are ]). Libertarians do not oppose force used in response to initiatory aggressions such as violence, fraud or trespassing. Libertarians favor an ethic of self-responsibility and strongly oppose the ], because they believe ''forcing'' someone to provide aid to others is ethically wrong, ultimately counter-productive, or both. | |||

| ====Direct==== | |||

| ''Note on terminology'': Some writers who have been called libertarians have also been referred to as ''classical liberals'', by others or themselves. And, some use the phrase "''the freedom philosophy''" to refer to libertarianism, ], or both. | |||

| ] is a political system where the citizens vote on all major policy decisions. It is called ''direct'' because, in the classical forms, there are no intermediaries or representatives. Current examples include many small civic organizations (like college faculties) and town meetings in New England (usually in towns under 10,000 population). Critics note that it sometimes emphasises the act of voting more than other democratic procedures such as free speech and press and civic organisations. That is, these critics argue, democracy is more than merely a procedural issue.<ref> Jane J. Mansbridge. ''Beyond Adversary Democracy'' (1983)</ref> | |||

| {{Political ideology entry points}} | |||

| All direct democracies to date have been relatively small communities; usually ]s. Today, a limited direct democracy exists in some ] ] that practice it in its literal form. Direct democracy obviously becomes difficult when the electorate is large--for example some 30,000 or more citizens were eligible in ]. However, the extensive use of ], as in ], is akin to direct democracy in a very large polity with over 20 million potential voters.<ref>John M. Allswang. ''The Initiative and Referendum in California, 1898-1998'' (2000) (ISBN 0804738211) </ref> Modern direct democracy tries accommodate this problem and sees a role for strictly controlled representatives. It is characterised by three pillars; ]s (initiated by governments or legislatures or by citizens responding to legislation), ]s (initiated by citizens) and ]s (on holders of public office). | |||

| ==Principles== | |||

| {{main|Libertarian views of rights|Libertarian theories of law}} | |||

| Libertarians generally define liberty as the freedom to do whatever one wishes up to the point that one's behavior begins to interfere with or endanger another's person or property. At the point of interference, each party would become subject to certain principled rules for ], which emphasize compensation to the victim rather than punishment or retribution alone. Most libertarians allow that such sanctions are properly imposed by the state in the form of criminal or civil penalties, though many dispute the degree to which such punishment is necessarily a state function. | |||

| ====Representative==== | |||

| Libertarians generally view constraints imposed by the state on persons or their property, beyond the need to penalize infringement of one's rights by another, as a violation of liberty. Anarchists favor no governmental constraints at all, based on the assumption that rulers and laws are unnecessary because in the absence of government individuals will naturally form self-governing social bonds and rules. In contrast, Big-L-Libertarians consider government necessary for the sole purpose of protecting the rights of the people. This includes protecting people and their property from the criminal acts of others, as well as providing for national defense. | |||

| ] is so named because the people select representatives to a governing body. Representatives may be chosen by the electorate as a whole (as in many ] systems) or represent a particular district (or ]), with some systems using a combination of the two. Some representative democracies also incorporate some elements of direct democracy, such as ]. Representative democracy is susceptable to various problems such ] of constituencies. | |||

| ====Liberal==== | |||

| Libertarians generally defend the ideal of freedom from the perspective of how little one is constrained by authority, that is, how much one is ''allowed'' to do, which is referred to as ]. This ideal is distinguished from a view of freedom focused on how much one is ''able'' to do, which is termed ], a distinction first noted by ], and later described in fuller detail by ]. | |||

| ] is a representative democracy (with free and fair elections) along with the protection of minorities, the ], a ], and protection of ] (thus the name ''liberal'') of speech, assembly, religion, and property. Conversely, an ] is one where the protections that form a liberal democracy are either nonexistent, or not enforced. The experience in some ] states drew attention to the phenomenon, although it is not of recent origin. ] for example used plebiscites to ratify his imperial decisions. | |||

| æ | |||

| Many libertarians view ], ], and ] as the ultimate rights possessed by individuals, and that compromising one necessarily endangers the rest. In democracies, they consider compromise of these individual rights by political action to be "tyranny by the majority", a term first coined by ], and made famous by ], which emphasizes the threat of the majority to impose majority norms on minorities, and violating their rights in the process. "...there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling, against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them..." | |||

| Many libertarians favor ], which they see as less arbitrary and more adaptable than ]. The relative benefits of common law evolving toward ever finer definitions of property rights were articulated by thinkers such as ], ], ], and ]. Some libertarian thinkers believe that this evolution can define away various "commons" such as pollution or other interactions viewed by some as ]. "A libertarian society would not allow anyone to injure others by pollution because it insists on individual responsibility."<ref>"I'm for a free market. I only oppose the misuse of technology. A libertarian society would not allow anyone to injure others by pollution because it insists on individual responsibility. That's part of the beauty of libertarianism." -]</ref> "Public" ownership of property makes accountability difficult. | |||

| === Natural rights and consequentialism === | |||

| Some libertarians such as ] and ] view the rights to life, liberty, and property as ], i.e., worthy of protection as an end in themselves. Their view of natural rights is derived, directly or indirectly, from the writings of ] and ]. ], another powerful influence on libertarianism, despite rejecting the label, also viewed these rights as based on ]. | |||

| Other libertarians such as ], ], and ] justified these rights on ] or ], as well as moral grounds. They argued that libertarianism was consistent with economic efficiency, and thus, the most effective means of promoting or enhancing social welfare. They may also justify some initiation of force in some situations, such as in emergency situations. Some libertarians such as ] take the contractarian point of view that rights are a sort of agreement rational people would make before interacting. | |||

| == Libertarian policy == | |||

| ] and ]'s ], consider the ] to be an important symbol of their ideas.]] | |||

| Libertarians strongly oppose infringement of civil liberties such as restrictions on free expression (e.g., speech, press, or religious practice), prohibitions on voluntary association, or encroachments on persons or property except as a result of ] to establish or punish criminal behavior. As such, libertarians oppose any type of ] (i.e., claims of offensive speech), or pre-trial forfeiture of property. Furthermore, most libertarians reject the distinction between political and commercial speech or association, a legal distinction often used to protect one type of activity and not the other from government intervention. | |||

| Libertarians also frown on any laws restricting personal or ] behavior, as well as laws on ]s. As such, they believe that individual choices for products or services should not be limited by government licensing requirements or state-granted monopolies, or in the form of ]s that restrict choices for products and services from other nations (see ]). They also tend to oppose legal prohibitions on ], ], and ]. They believe that citizens should be free to take risks, even to the point of actual harm to themselves. For example, while most libertarians may personally agree with the majority who favor the use of ]s, libertarians reject ''mandating'' their use as ]. Similarly, many believe that the United States ] (and other similar bodies in other countries like ] in Canada) shouldn't ban unproven medical treatments, that any decisions on treatment be left between patient and doctor, and that government should, at most, be limited to passing non-binding judgments about efficacy or safety. | |||

| Libertarians generally believe that such freedoms are a universal birthright, and they accept any material inequalities or wanton behavior, as long as it harms no one '''else''', likely to result from such a policy of governmental non-intervention. They see economic inequality as an outcome of people's freedom to choose their own actions, which may or may not be profitable. | |||

| ===Minarchism and Anarcho-capitalism=== | |||

| {{main|Minarchism|Anarcho-capitalism}} | |||

| Some who self-identify as libertarians are ]s, i.e., supportive of minimal taxation as a "necessary evil" for the limited purpose of funding public institutions that would protect civil liberties and property rights, including ], volunteer ] without ], and judicial ]s. ], by contrast, oppose all ]ation, rejecting any government claim for a ] as unnecessary. They wish to keep the government out of matters of justice and protection, preferring to delegate these issues to private groups. Anarcho-capitalists argue that the minarchist belief that any ] can be contained within any reasonable limits is unrealistic, and that institutionalized coercion on any scale is counterproductive. | |||

| The policy positions of minarchists and anarcho-capitalists on mainstream issues tend to be indistinguishable as both sets of libertarians believe that existing governments are too intrusive. Some libertarian philosophers such as ] argue that, properly understood, minarchism and anarcho-capitalism are not in contradiction. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{main |

{{main|History of democracy}} | ||

| ]. | |||

| {{legend|#0000FF|Governments that claim to be democratic and allow the existence of opposition groups, at least in theory.}} | |||

| {{legend|#00CC00|Governments that claim to be democratic but do not allow the existence of opposition groups.}} | |||

| {{legend|#FF0000|Governments that do not claim to be democratic.}}]] | |||

| ===Ancient origins=== | |||

| The word ''democracy'' was coined in ] and used interchangeably with ]<ref name=HerodotusLots>Herodotus. 3.80</ref> (equality of political rights). Although ] is today considered by many to have been a form of direct democracy originally it had two distinguishing features: firstly the allotment (selection by lot) of ordinary citizens to government offices and courts,<ref>Aristotle Book 6</ref><ref name=HerodotusLots /> and secondarily the assembly of all the citizens. In theory, all the Athenian citizens were eligible to speak and vote in the Assembly, which set the laws of the city-state, but neither political rights, nor citizenship, were granted to ], ], or ]. Of the 250,000 inhabitants only some 30,000 on average were citizens. Of those 30,000 perhaps 5,000 might regularly attend one or more meetings of the popular Assembly. Key to the development of Athenian democracy was its huge juries allotted from the citizenry <ref>Aristotle, Politics 2.1274a, c350BC</ref>. Most of the officers & magistrates of Athenian government were ]; only the generals (strategoi) and a few other officers were elected. <ref>Morgens Herman Hansen, The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes, ISBN 1-85399-585-1, P.231-2)</ref> | |||

| The seeds of representative democracy were arguably started in the ]. Democratic principles and elements were found in societies ranging from ]n ], ]s, ]s and ]s , to certain ] and ]s such as the ]. However, since usually only a minority had political rights they are often better described as ].<ref> For example, in the ] only the males of certain clans could be leaders and some clans were excluded. Only the oldest females from the same clans could chose and remove the leaders. This excluded most of the population. An interesting detail is that there should be consensus among the leaders, not majority support decided by voting, when making decisions.</ref> | |||

| The first known use of a term that has been translated as "libertarian," in a political sense, was by anarcho-communist ], who used the French term "libertaire" in a letter to Proudhon in 1857.<ref>Déjacque, Joseph. </ref> While many left-anarchists still use the term (e.g., terms translatable as "libertarian" are used as a synonym for ] in some non-English languages, like French, Italian and so on), its most common usage in the United States has nothing to do with socialism. | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| Instead, libertarianism as a political ideal is viewed as a form of ], a modern term often used interchangeably with libertarianism. This concept, originally referred to simply as "liberalism," arose from ] ideas in Europe and America, including the political philosophies of ] and the ], and the moral and economic philosophy of ]. By the late 18th century, these ideas quickly spread with the ] throughout the ]. | |||

| During the ], there were various systems involving elections or assemblies, such as the election of ] in ], the ], the ] in ], certain ] city-states such as ], the ] system in early medieval ], the ] in ] countries, and ]n ]. | |||

| The ] had its roots in the restrictions on the power of kings written into ]. The first elected parliament was ] in England in 1265. However only a small minority actually had a voice; Parliament was elected by only a few percent of the population (less than 3% in 1780.), and the system had problematic features such as ]. The power to call parliament was at the pleasure of the monarch (usually when he or she needed funds). After the ] of 1688, the ] was enacted in ], which codified certain rights and increased the influence of the Parliament. The franchise was slowly increased and the Parliament gradually gained more power until the monarch became entirely a figurehead. | |||

| Locke developed a version of the ] as rule with "the ]" derived from ]. The role of the legislature was to protect natural rights in the legal form of ]s. Locke built on the idea of natural rights to propose a labor theory of property; each individual in the ] "owns" himself and, by virtue of their ], owns the fruits of his efforts. From this conception of natural rights, an economy emerges based on ] and ], with ] as the medium of exchange. | |||

| ===18th and 19th centuries=== | |||

| At around the same period, the French philosopher Montesquieu developed a distinction between sovereign and administrative powers, and proposed a ] among the latter as a counterweight to the natural tendency of administrative power to grow at the expense of individual rights. He allowed as to how this separation of powers could work just as well in a ] as for a limited monarchy, though he personally preferred the latter. Nevertheless, his ideas fed the imaginations of America's ], and would become the basis upon which political power would be exercised by most governments, both constitutional monarchies and republics, beginning with the United States. | |||

| The ] can be seen as the first liberal democracy with relatively wide franchise. The ] protected rights and liberties and was adopted in 1788. Already in the colonial period before 1776 most adult white men could vote; there were still property requirements but most men owned their own farms and could pass the tests. On the ], democracy became a way of life, with widespread social, economic and political equality.<ref>Ray Allen Billington, ''America's Frontier Heritage'' (1974) 117-158. However the frontier did not produce much democracy in Canada, Australia or Russia. </ref>By 1840s almost all property restrictions were ended and nearly all white adult male citizens could vote; and turnout averaged 60-80% in frequent elections for local, state and national officials. The Americans invented the grass roots party that could mobilise the voters, and had frequent elections and conventions to keep them active. The system gradually evolved, from ] or the ] to ] or the ] and later to the ]. In ] after the Civil War (late 1860s) the newly freed slaves became citizens, and they were given the vote as well. | |||

| Later in 1789, ] adopted the ] and, although short-lived, the ] was elected by all males. ] is widely recognized as the second oldest constitution in the world.<ref name="Markoff">] describes the advent of modern codified national constitutions as one of the milestones of democracy, and states that "The first European country to follow the U.S. example was Poland in 1791." John Markoff, ''Waves of Democracy'', 1996, ISBN 0-8039-9019-7, p.121.</ref> | |||

| Adam Smith's moral philosophy stressed government non-intervention so that individuals could achieve whatever their "God-given talents" would allow without interference from arbitrary forces. His economic analysis suggested that anything interfering with the ability of individuals to contribute their best talents to any enterprise--a reference to ] policies and ] ]--would lead to an inefficient division of labor, and hamstring progress generally. Smith stated that "a voluntary, informed transaction always benefits both parties," such that "voluntary" and "informed" meant the absence of force or fraud. | |||

| Liberal democracies were few and often short-lived before the late nineteenth century. Various nations and territories have claimed to be the first with ]. | |||

| During the ], the ] substantially enshrined the protection of liberty as the primary purpose of government. Thomas Jefferson said that "rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others." | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| The ] imported American ideas of liberty, although some might say ''re-imported'', in drafting the French Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1789, which states: | |||

| [[Image:Freedom House world map 2005.png|thumb|350px| | |||

| :''Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights.'' | |||

| This map reflects the findings of ]'s survey ], which reports the state of world freedom in 2005. It is one of the most widely used measures of democracy by researchers. | |||

| {{legend|#219A57|Free.}} Freedom House considers these to be liberal democracies. | |||

| {{legend|#FFC27B|Partly Free}} | |||

| {{legend|#B30000|Not Free}}]] | |||

| 20th century transitions to liberal democracy have come in successive "waves of democracy", variously resulting from wars, revolutions, ] and economic circumstances. ] and the dissolution of the ] and ] empires resulted in the creation of new nation-states in Europe, most of them nominally democratic. In the 1920 democracy flourished, but the ] brought a disenchantment and most of the countries of Europe, Latin America and Asia turned to strong-man rule or dictatorships. Thus the rise of ] and dictatorships in ], Italy, Spain and Portugal, as well as nondemocratic regimes in Poland, the Baltics, the Balkans, Brazil, Cuba, China, and Japan, among others. Together with Stalin's regime in the ], these made the 1930s the "Age of Dictators"{{fact}}. | |||

| ] brought a definitive reversal of this trend in western Europe. The successful democratisation of the ] and the ] served as a model for the later theory of ]. However, most of ] was forced into the non-democratic ]. The war was followed by ], and again most of the new independent states had nominally democratic constitutions.In the decades following World War II, most western democratic nations had a predominantly ] and developed a ], reflecting a general consensus among their electorates and political parties. In the 1950s and 1960s, economic growth was high in both the western and ] countries; it later declined in the state-controlled economies. By 1960, the vast majority of nation-states were nominally democracies, although the majority of the world's populations lived in nations that experienced sham elections, and other forms of subterfuge (particularly in Communist nations and the former colonies.) | |||

| ], in a reformulation of ]'s notion of ], stated that, "Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign." Mill contrasts this with what he calls the "tyranny of the majority," declaring that utilitarianism requires that political arrangements satisfy the "]", whereby each person would be guaranteed the greatest possible liberty that would not interfere with the liberty of others, so that each person may maximize his or her happiness. This ideal would be echoed later by English philosopher ] when he espoused the "law of equal liberty," stating that "every man has freedom to do all that he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man." | |||

| ]-]]] | |||

| ] advocated an ] version of social contract which was not between individuals and the state, but rather "an agreement of man with man; an agreement from which must result what we call society". One of his famous statements is that "anarchy is order." In his formulation of ], he asserted that labor is the only legitimate form of property, stating "property is freedom", rejecting both private and collective ownership of property "]". However, he later abandoned his rejection of property, and endorsed private property "as a counterweight to the power of the State, and by so doing to insure the liberty of the individual." | |||

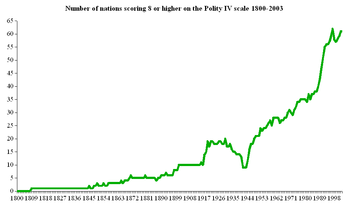

| ]-] scoring 8 or higher on Polity IV scale, another widely used measure of democracy.]] | |||

| A subsequent wave of ] brought substantial gains toward true liberal democracy for many nations. Several of the military dictatorships in ] became democratic in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This was followed by nations in ] and ] by the mid- to late 1980s. Economic malaise in the 1980s, along with resentment of communist oppression, contributed to the ], the associated end of the ], and the democratisation and ] of the former ] countries. The most successful of the new democracies were those geographically and culturally closest to western Europe, and they are now members or candidate members of the ]. The liberal trend spread to some nations in ] in the 1990s, most prominently in ]. Some recent examples include the ], the ] in ], the ] in ], the ] in ], the ] in ], and the ] in ]. | |||

| By the early 20th century, mainstream thought in many parts of the world began to diverge from an almost exclusive focus on negative liberty and free markets to a more positive assertion of rights promoted by the ] in the United States and the ] movement in Europe. Rather than government existing merely to "secure the rights" of free people, many began to agitate for the use of government power to promote positive rights. This change is exemplified by ]'s ], two of which are negative, namely restricting governments from infringing "freedom of speech" and "freedom of worship," and two of which were positive, declaring a "freedom from want", i.e., government delivery of domestic and foreign aid, and a "freedom from fear", i.e., an internationalist policy for imposing peace between nations. | |||

| The number of liberal democracies currently stands at an all-time high and has been growing without interruption for some time. As such, it has been speculated that this trend may continue in the future to the point where liberal democratic nation-states become the universal standard form of human ]. This prediction forms the core of ]'s "]" theory. | |||

| As "liberal" came to be identified with Progressive policies in several English-speaking countries during the 1920s and 1930s, many of those who espoused the original, minimal-state philosophy began to distinguish their doctrine by calling themselves "classical liberals." | |||

| ===Marxist/Socialist view=== | |||

| In the early 20th century, the rise of ] in Germany and ] in Russia were generally seen as distinct movements, with the latter bearing more resemblance to the Progressive movement in the West, and gaining much sympathy from many of its advocates. A group of central European economists called the ] challenged that distinction between various brands of ] by identifying the common ] underpinning to their doctrines, and claiming that collectivism in all its forms is inherently antithetical to liberty as traditionally understood in the West. These thinkers included ], ], and ], the latter describing the "] as the linchpin" of libertarianism. The Austrian School had a powerful impact on both economic teaching and libertarian principles. In the latter half of the 20th century, the term "libertarian," which had earlier been associated with anarchism, came to be adopted by those whose attitudes bore closer resemblance to "classical liberals." | |||

| {{sect-stub}} | |||

| Many on the left view democracy as essentially a system giving ordinary people power and therefore they view ], ], etc. as inherently democratic because they believe they give power to the working classes. As a result many left-wing political groups in the 18th and 19th century referred to themselves as democrats or their party as "democratic" (Notable examples include the ] & the US ]) | |||

| Social-Democrats see liberal democracy as being compatible with the interests of working class and therefore participate in elections. According to their views once in power Socialists can improve popular welfare without needing to change the economic state. | |||

| In 1955, ] wrote an article pondering what to call those, such as himself, who subscribed to the ] philosophy of individualism and self-responsibility. He said, | |||

| The ] view is fundamentally opposed to liberal democracy believing that the capitalist state cannot be democratic by its nature, as it represents the dictatorship of the ]. Marxism views liberal democracy as an unrealistic ]. This is because they believe that in a capitalist state all "independent" media and most political parties are controlled by capitalists and one either needs large financial resources or to be supported by the bourgeoisie to win an election. According to Marx, "Universal suffrage (i.e. parliamentary elections) is an opportunity citizens of a country get every four years to decide who among the ruling classes will misrepresent them in parliament."<ref></ref> Thus the Marxists believe that in a capitalist state, the system focuses on resolving disputes within the ruling bourgeosie class and ignores the interests of the proletariat or labour class which are not represented and therefore dependent on the bourgeoisie's good will. Moreover, even if representatives of the proletariat class are elected in a capitalist country they have limited power over the country's affairs as the economic sphere is largely controlled by private capital and therefore the representative's power to act is curtailed. Essentially, in the ideal liberal state the functions of the elected government should be reduced to the minimum (i.e. the court system and security). | |||

| :''Many of us call ourselves "liberals," And it is true that the word "liberal" once described persons who respected the individual and feared the use of mass compulsions. But the leftists have now corrupted that once-proud term to identify themselves and their program of more government ownership of property and more controls over persons. As a result, those of us who believe in freedom must explain that when we call ourselves liberals, we mean liberals in the uncorrupted classical sense. At best, this is awkward, subject to misunderstanding. Here is a suggestion: Let those of us who love liberty trademark and reserve for our own use the good and honorable word "libertarian."''<ref>Russell, Dean. , Ideas on Liberty, May 1955</ref> | |||

| ==Theory== | |||

| ===Libertarian philosophy in the academy=== | |||

| ===Conceptions=== | |||

| Seminars in libertarianism were being taught in the U.S. starting in the 1960's, including a personal studies seminar at SUNY Geneseo starting in 1972. The ], later renamed Rampart College, was operated by ] during the 1960s and became a significant influence in spreading libertarian ideas. | |||

| Among political theorists, there are many contending conceptions of democracy. | |||

| *Under ''minimalism'', democracy is a system of government in which citizens give teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not “rule” because on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not very intelligent. ] articulated this view most famously in his book ''Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy'' <ref>], (1950). ''Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy''. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-133008-6.</ref>. Contemporary proponents of minimalism include ], ], and ]. | |||

| Philosophical libertarianism gained a significant measure of recognition in the academy with the publication of Harvard professor ]'s ''Anarchy, State, and Utopia'' in 1974. Left-liberal philosopher ] famously argued that Nozick's libertarianism was 'without foundations' because Nozick's libertarianism proceeded from the assumption that individuals owned themselves without any further explanation. | |||

| *The ''aggregative'' conception of democracy holds that government should produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter — with half to his left and the other half to his right. ] laid out this view in his 1957 book ''An Economic Theory of Democracy''. <ref>], (1957). ''An Economic Theory of Democracy''. Harpercollins College. ISBN 0-06-041750-1.</ref> | |||

| ] aimed to meet this challenge. Based on the work of ], Narveson developed contractarian libertarianism, outlined in his 1988 work ''The Libertarian Idea'', and then extended in his 2002 work ''Respecting Persons in Theory and Practice''. In these works, Narveson agreed with Hobbes that individuals would lay down their ability to kill and steal from each other in order to leave the state of nature, but he broke with Hobbes in arguing that an absolute state was not necessary to enforce this agreement. Narveson argues that no state at all is required. Other advocates of contractarian libertarianism include the Nobel Laureate and founder of the ] school of economics ], and Hungarian-French philosopher ]. | |||

| *'']'' is based on the notion that democracy is government by discussion. Deliberative democrats contend that laws and policies should be based upon reasons that all citizens can accept. The political arena should be one in which leaders and citizens make arguments, listen, and change their minds. The modern proponents of this form of government are led by ]. | |||

| By contrast, J. C. Lester aimed to undermine the challenge by defending libertarianism without foundations in the form of ] libertarianism, most notably in his 2000 work ''Escape from Leviathan''. In particular, that work applies critical rationalism to defend the thesis that there are no systematic practical clashes among instrumental rationality, interpersonal liberty, social welfare and private-property anarchy. | |||

| *The conceptions above assume a representative democracy. '']'' holds that citizens should participate directly, not through their representatives, in making laws and policies. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not really rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies. | |||

| ===Left-libertarians=== | |||

| *Another conception of democracy is that it means ''political equality'' between all citizens. It is also used to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions, procedures and patterns which are perceived as leading to equality in political power. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open ] which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. This meaning of the word "democracy" has also been called ]. This view may see it as a problem that the majority of the voters decide policy, as opposed to majority rule of the entire population. This can be used as an argument for making political participation mandatory, like compulsory voting. It may also see a problem with the wealthy having more influence and therefore argue for reforms like ].<ref> ], (1989). ''Democracy and its Critics.'' New Haven: Yale University Press.</ref> | |||

| {{main|Left-libertarianism}} | |||

| ==="Democracy" and "Republic"=== | |||

| There is also a camp of libertarians in Anglo-American Political Philosophy who hold egalitarian principles with the ideas of individual freedom and property rights. They call themselves "left-libertarians". ]s believe that the initial distribution of property is naturally egalitarian in nature, such that either persons cannot legally appropriate property privately and exclusively or they must obtain permission of all within the political community to do so. Some left-libertarians even use the ] in such a way as to promote redistributive types of justice in ways seemingly compatible with libertarian rights of self-ownership. Some left-libertarians in modern times include ], ], ], and ], whose book ''Libertarianism Without Inequality'' is one of the most egalitarian leaning libertarian texts currently in publication. | |||

| In contemporary usage, the term "democracy" refers to a government chosen by the people, whether it is direct or representative. The term "]" has many different meanings but today often refers to a representative democracy with an elected ], such as a ], serving for a limited term, in contrast to states with a hereditary ] as a head of state, even if these states also are representative democracies with an elected ] such as a ]. | |||

| In historical usages and especially when considering the works of the ], the word "democracy" refers solely to ], while a ] where representatives of the people govern in accordance with ] and usually also a ] is referred to as a ]. Using the term "democracy" to refer solely to direct democracy retains some popularity in United States ] and ] circles. | |||

| Criticisms of left-libertarianism have come from both the right and left alike. Right-libertarians like Robert Nozick hold that self-ownership and property acquisition need not meet egalitarian standards, they must merely follow the Lockean idea of not worsening the situation of others. ], an ] philosopher, has extensively criticized left-libertarianism's virtues of self-ownership and equality. In his ''Self-ownership, Freedom, and Equality'', Cohen claims that any system that takes equality and its enforcement seriously is not consistent with the robust freedom and full self-ownership of libertarian thought. ] of the Cato Institute has responded to Cohen's critique in ''Critical Review'' and has provided a guide to the literature criticizing libertarianism in his bibliographical review essay on "The Literature of Liberty" in ''The Libertarian Reader'', ed. David Boaz. | |||

| The original framers of the ] were notably ] of what they perceived as a danger of majority rule in oppressing freedom and ] of the individual. For example, ], in ], advocates a constitutional republic over a democracy to protect the individual from the majority. <ref>James Madison, (], ]). , ''Daily Advertiser''. ]. Republished by ].</ref> The framers carefully created the institutions within the Constitution and the ]. They kept what they believed were the best elements of majority rule. But they were mitigated by a constitution with protections for individual liberty, a ], and a layered federal structure. | |||

| ===Objectivism=== | |||

| {{main|Libertarianism and Objectivism}} | |||

| ]'' magazine dedicated an issue to ]'s influence one hundred years after her birth.]] | |||

| Libertarianism's status is in dispute among those who style themselves ] (Objectivism is the name novelist ] gave her philosophy). Though elements of Rand's philosophy have been adopted by libertarianism, Objectivists (including Rand herself) have condemned libertarianism as a threat to freedom and capitalism. In particular, it has been claimed that libertarians use Objectivist ideas "with the teeth pulled out of them".{{fact}} | |||

| ] and ] have complex relationships to democracy and republic. See these articles for more details. | |||

| Conversely, some libertarians see Objectivists as dogmatic, unrealistic, and uncompromising. According to ] editor ] in the magazine's March 2005 issue focusing on Objectivism's influence, Rand is "one of the most important figures in the libertarian movement... Rand remains one of the best-selling and most widely influential figures in American thought and culture" in general and in libertarianism in particular. Still, he confesses that he is embarrassed by his magazine's association with her ideas. In the same issue, ] says that "Libertarianism, the movement most closely connected to Rand's ideas, is less an offspring than a rebel stepchild." Though they reject what they see as Randian dogmas, libertarians like Young still believe that "Rand's message of reason and liberty... could be a rallying point" for libertarianism. | |||

| ===Constitutional monarchs and upper chambers=== | |||

| US military operations in Iraq have highlighted the tensions between Objectivism and the views of many libertarians. Objectivists have often disagreed with the ] (often misleadingly called "]") of many libertarians. They have argued that it is right for the state to take pre-emptive military action when the evidence suggests a genuine risk that another state will initiate coercive use of physical force. Many also would like to see the state more aggressively protect the rights of US individuals and corporations abroad - including military action in response to nationalization. | |||

| Initially after the American and French revolutions the question was open whether a democracy, in order to restrain unchecked majority rule, should have an elitist ], the members perhaps appointed meritorious experts or having lifetime tenures, or should have a ] with limited but real powers. Some countries (as Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries and Japan) turned powerful monarchs into constitutional monarchs with limited or, often gradually, merely symbolic roles. Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system (as in the U.S., France, China, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Egypt). In Australia, the monarchy is seen as hollow shell. However, there is no consensus on how to ]. Most voters want a powerful president (as in the U.S., France, and Russia), while most politicians want to keep the parliamentary system and have only a weak president (as in Italy and Germany). Many nations had elite upper houses of legislatures which often had lifetime tenure, but eventually these senates lost power (as in Britain) or else became elective and remained powerful (as in the United States). | |||

| === Democratic state=== | |||

| Objectivists reject the oft-heard libertarian refrain that state and government are "necessary evils": for Objectivists, a government limited to protection of its citizens' rights is absolutely necessary and moral. Objectivists are opposed to all anarchist currents and are suspicious of libertarians' lineage with ]. | |||

| Though there remains some ] debate as to the applicability and legitimacy of criteria in defining democracy what follows may be a minimum of requirements for a state to be considered democratic (note that for example anarchists may support a form of democracy but not a state): | |||

| # A ''demos''—a group which makes political decisions by some form of collective procedure—must exist. Non-members of the demos do not participate. In modern democracies the demos is the adult portion of the ], and adult ] is usually equivalent to membership. | |||

| ==Politics of libertarian parties== | |||

| # A ''territory'' must be present, where the decisions apply, and where the demos is resident. In modern democracies, the territory is the ], and since this corresponds (in theory) with the homeland of the nation, the demos and the reach of the democratic process neatly coincide. Colonies of democracies are not considered democratic by themselves, if they are governed from the colonial ]: demos and territory do not coincide. | |||

| # A ''decision-making procedure'' exists, which is either direct, in instances such as a ], or indirect, of which instances include the election of a ]. | |||

| # The procedure is regarded as ''legitimate'' by the demos, implying that its outcome will be accepted. ] is the willingness of the population to accept decisions of the state, its government and courts, which go against personal choices or interests. | |||

| # The procedure is ''effective'' in the minimal sense that it can be used to change the government, assuming there is sufficient support for that change. Showcase elections, pre-arranged to re-elect the existing regime, are not democratic. | |||

| # In the case of nation-states, the state must be ]: democratic elections are pointless if an outside authority can overrule the result. | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| Libertarianism is often viewed as a ] movement, especially by non-libertarians in the ], where libertarians tend to have more in common with traditional ] than ]s, especially with regard to economic and ] policies. However, many describe libertarians as being "conservative" on economic issues and "liberal" on social issues. (For example, most libertarians view Texas congressman and former Libertarian U.S. Presidential candidate ] (R-14) to be a philosophical libertarian, even though he is technically affiliated with the Republican Party.) | |||

| ] oppose "coercive" majority rule. Many support a non-hierarchical and non-coercive system of ] within free associations. ] argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognized that majority decisions are not binding on the minority. The minority can refuse to consent and are free to leave and form or join another association.<ref>]. </ref> There are also some anarchists who expect society to operate by ].<ref> As in '']'' or '']''</ref> | |||

| Some ], ], and ] groups oppose democracy. | |||

| A historical example of libertarian politics would be discrimination in the workplace. Liberals typically support laws to penalize employers for discrimination on a basis unrelated to the ability to do the job while conservatives historically favored laws that enforced such discrimination (as in the pre-civil rights South). Libertarians could be expected to oppose any laws on this matter because these would infringe on the property rights or freedoms of either the business owner or the just-hired employee. In other words, one should be free to discriminate against others in their personal or business dealings (within the constaints of principal/agency agreements); one should be free to choose where they accept work, or to start one's own business in accordance with their personal beliefs and prejudices; and one should be free to lead a boycott or publicity campaign against businesses with whose policies they disagree. | |||

| For criticisms of specific forms of democracy, see the appropriate article. | |||

| ] turns it to a plane to situate libertarianism in a wider gamut of political thought.]] In a more current example, conservatives are likely to support a ban on same-sex marriage in the interests of preserving traditional order, while liberals are likely to favor allowing same-sex marriage in the interest of guaranteeing equality under the law. Libertarians are likely to disagree with the notion of government-sanctioned marriage itself. Specifically, they would deny that the government deserves any role in marriage other than enforcing whatever legal contract people choose to enter, and to oppose the various additional rights currently granted to married people. | |||

| ==Beyond the state level== | |||

| Instead of a "left-right" spectrum, some libertarians use a two-dimensional space, with "personal freedom" on one axis and "economic freedom" on the other, which is called the ]. Named after ], who designed the chart and also founded the ], the chart is similar to a socio-political test used to place individuals by the ]. A first approximation of libertarian politics (derived from these charts) is that they agree with liberals on social issues and with conservatives on economic issues. Thus, the traditional linear scale of governmental philosophy could be represented inside the chart stretching from the upper left corner to the lower right, while the degree of state control is represented linearly from the lower left to the upper right. (See below for criticism of this chart and its use.) | |||

| While this article deals mainly with democracy as a system to rule countries, voting and representation have been used to govern many other kinds of communities and organisations. | |||

| * Many ] decide policy and leadership by voting. | |||

| == The Libertarian Movement == | |||

| * In business, corporations elect their boards by votes weighed by the number of ]s held by each owner. | |||

| ] is an international project to define and document key current and potential voluntary replacements of government programs. | |||

| * ]s sometimes choose their leadership through democratic elections. In the U.S. democratic elections were rare before Congress required them in the 1950s.<ref> Seymour Martin Lipset, ''Union Democracy'' (1962)</ref>. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Some, such as ], executive vice president of the libertarian U.S ], the ], argue that the term ''classical liberalism'' should be reserved for early liberal thinkers for the sake of clarity and accuracy, and because of differences between many libertarian and classical liberal thinkers. Nevertheless, the Cato Institute's official stance is that classical liberalism and libertarianism are synonymous; they prefer the term "liberal" to describe themselves, but choose not to use it because of its confusing connotation in some English-speaking countries (most self-described liberals prefer a ] rather than a free market economy). The Cato Institute dislikes adding "classical" because, in their view, "the word 'classical' connotes a backward-looking philosophy". Thus, they finally settle on "libertarian", as it avoids backward implications and confused definitions. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| Libertarians and their allies are not a homogeneous group, but have collaborated to form ]s, ], and other projects. For example, Austrian School economist ] co-founded the ], the ], and the ] to support an independent libertarian movement, and joined ] in founding the ] in 1971. (Rothbard ceased activity with the Libertarian Party in 1985 and some of his followers like ] are hostile to the group.) In the U.S. today, some libertarians support the Libertarian Party, some support no party, and some attempt to work within more powerful parties despite their differences. The ] (a wing of the ]) promotes libertarian views. A similar organization, the ], exists within the ], but is less organized. Republican Congressman ] is also a member of the Libertarian Party and was once its presidential candidate. | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| ] is one of the most successful libertarian political parties in the world.]]]'s ] (Libertarian Movement) is a prominent, non-U.S. libertarian party which holds roughly 10% of the seats in Costa Rica's national assembly (legislature). The Movimiento Libertario is considered the first libertarian organization to achieve substantial electoral success at the national level, though not without controversy. For example, Rigoberto Stewart, co-founder of the party and founder of "The Limón REAL Project" for autonomy in a province in Costa Rica, and director of INLAP, a libertarian think tank, lost his influence within Movimiento Libertario and support for "The Limón REAL Project". As perhaps explained by ], while accepting money from the ], a ] liberal foundation, the party compromised on their libertarian principles in return for more power, turning to anti-libertarian positions. | |||

| * Joyce Appleby, ''Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination'' (1992) | |||

| * Becker, Peter, Juergen Heideking and James A. Henretta, eds. ''Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750-1850.'' Cambridge University Press. 2002. | |||

| * Benhabib, Seyla, ed., ''Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political'' (Princeton University Press, 1996) | |||

| *], ''From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First'', Oxford University Press, 2000, ch. 5. ISBN 0-19-829688-6 | |||

| * Castiglione, Dario. "Republicanism and its Legacy," ''European Journal of Political Theory'' (2005) v 4 #4 pp 453-65. | |||

| * Copp, David, Jean Hampton, and John E. Roemer, eds. ''The Idea of Democracy'' Cambridge University Press (1993) | |||

| * Dahl, Robert. ''Democracy and its Critics'', Yale University Press (1989) | |||

| * Dahl, Robert. ''On Democracy'' Yale University Press, 2000 | |||

| * Dahl, Robert. Ian Shapiro, and Jose Antonio Cheibub, eds, ''The Democracy Sourcebook'' MIT Press 2003 | |||

| * Diamond, Larry and Marc Plattner, ''The Global Resurgence of Democracy'', 2nd edition Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996 | |||

| * Diamond, Larry and Richard Gunther, eds. ''Political Parties and Democracy'' (2001) | |||

| * Diamond, Larry and Leonardo Morlino, eds. ''Assessing the Quality of Democracy'' (2005) | |||

| * Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Philip J. Costopoulos, eds. ''World Religions and Democracy'' (2005) | |||

| * Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Daniel Brumberg, eds. ''Islam and Democracy in the Middle East'' (2003) | |||

| * Elster, Jon (ed.). ''Deliberative Democracy'' Cambridge University Press (1997) | |||

| * Gabardi, Wayne. "Contemporary Models of Democracy," ''Polity'' 33#4 (2001) pp 547+. | |||

| * Held, David. ''Models of Democracy'' Stanford University Press, (1996), reviews the major interpretations | |||

| * Inglehart, Ronald. ''Modernization and Postmodernization. Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies'' Princeton University Press. 1997. | |||

| * Khan, L. Ali, ''A Theory of Universal Democracy.'' Martinus Nijhoff Publishers(2003) | |||

| * Lijphart, Arend. ''Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries'' Yale University Press (1999) | |||

| * Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy”, American Political Science Review, (1959) 53 (1): 69-105. online at JSTOR | |||

| * Macpherson, C. B. ''The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy.'' Oxford University Press (1977) | |||

| * Edmund Morgan, ''Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America'' (1989) | |||

| * Plattner, Marc F. and Aleksander Smolar, eds. ''Globalization, Power, and Democracy'' (2000) | |||

| * Plattner, Marc F. and João Carlos Espada, eds. ''The Democratic Invention'' (2000) | |||

| * Putnam, Robert. ''Making Democracy Work'' Princeton University Press. (1993) | |||

| * Riker, William H., ''] (1962) | |||

| * Sen, Amartya K. “Democracy as a Universal Value”, ''Journal of Democracy'' (1999) 10 (3): 3-17. | |||

| * Weingast, Barry. “The Political Foundations of the Rule of Law and Democracy”, ''American Political Science Review,'' (1997) 91 (2): 245-263. online at JSTOR | |||

| * Whitehead, Laurence ed. ''Emerging Market Democracies: East Asia and Latin America'' (2002) | |||

| * Wood, Gordon S. '' The Radicalism of the American Revolution'' (1993), examines democratic dimensions of republicanism | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| The Hong Kong Liberal Party is another example of a political party with libertarian leanings on the economic level. It is the second largest political party in the Legislative Council, however the majority of the party's success are a result of Hong Kong's unique electoral system which allows business groups to elect half the legislature while the other half is directly elected. | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| {{wiktionarypar|democracy}} | |||

| * | |||

| * in the ] | |||

| * | |||

| * — Worldwide democracy monitoring organization. | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * — Collection of resources on key issues of democracy and nation-building | |||

| * a university-level research and training pluri- and transdisciplinary school of democracy | |||

| *. | |||

| * | |||

| * by Fareed Zakaria | |||

| * | |||

| * — Global democracy network using information, participation and debate to empower citizens. | |||

| '''Critique''' | |||

| There are other ] that have had various amounts of success throughout the world. Libertarianism is emerging in ] with the inception of ] ("Cherished Liberty"), a thinktank and activist association that has 2000 members. Liberté Chérie gained significant publicity when it managed to draw 80,000 Parisians into the streets to demonstrate against government employees who were striking. | |||

| * | |||

| * — Democracy as the Community of Capital - A Provisional Critique of Democracy | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| '''Alternatives and improvements''' - see also , ] and ] | |||

| In 2001, the ] was founded by ], a political scientist and libertarian activist who argued that 20,000 libertarians should migrate to a single U.S. state in order to concentrate their activism. In August of 2003, the membership of the Free State Project chose ]. However, as of 2005, there are concerns over the low rate of growth in signed Free State Project participants. In addition, discontented Free State Project participants, in protest of the choice of New Hampshire, started rival projects, including the ], and , a project for a Free Alaskan Nation, to concentrate activism in a different state or region. There is also a . | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ===Controversies among libertarians=== | |||

| *, ''Ethics & Democracy'' | |||

| {{cleanup-section|March 2006}} | |||

| * | |||

| These controversies are addressed in separate articles: | |||

| * | |||

| *''']''': Most libertarians support ] and ] because they believe that people should be able to start and grow ], manufacture, transport, trade, buy, and sell with little to no interference from the government. Some may support efforts to limit private monopolies. Some libertarians like ] prefer ]s like ] to the ''status quo'' while others like ] see such programs as a threat to private industry and as a covert means of expanding government, and instead would abolish tax-funded schools altogether.<ref>Rockwell, Llewellyn H. Jr. ''''</ref>. Many ]s define 'capitalism' in its original marxian sense of state capitalism, and therefore oppose it. | |||

| * — Plan to limit global competition and facilitate the emergence of a sustainable, sane global civilization. | |||

| * | |||

| *''']''': Some libertarians believe that logical consistency to fundamental libertarian maxims (non aggression, individual rights)<ref>The maxims are described in the introduction of this article. Tenet is a principle, belief, or doctrine generally held to be true.(Meraim Webster) I.e. it is generally held to be true that as a fundamental maxim all human interaction should be voluntary and consensual.</ref> allows no taxation at all,<ref>"The libertarian, if he is to be logically consistent, must urge zero crime, not a small amount of it. Any crime is anathema for the libertarian. Any government, no matter how “nice,” must therefore also be rejected by the libertarian." Walter Block, GOVERNMENTAL INEVITABILITY: REPLY TO HOLCOMBE, JOURNAL OF LIBERTARIAN STUDIES VOLUME 19, NO. 3 (SUMMER 2005): 71–93</ref> while proponents of limited government might support low taxes, arguing that a society with no taxation would have difficulty providing ]s such as ]. ''See also: ].'' | |||

| * — "an experiment that asks: if there were no laws in the United States, what laws would you impose on America?" | |||

| * | |||

| *''']''': Most libertarians ally politically with modern conservatives over economic issues and gun laws (but for a libertarian defense of gun control, see here ). On many social issues, libertarians ally with modern left-wing politics. Foreign policy is a hotly debated issue among libertarians, because most libertarians oppose wars, against conservative wishes, but also oppose the ], against liberal wishes. Others ally with ], ] ], despite sharp disagreement on economic and social issues. Others refuse to ally with any political party other than their own and will never vote for a mainstream candidate. Most voting libertarians typically will only vote for a candidate that is philosopically libertarian, a good example of which in the U.S. is congressman ] (TX-R-14). Those that choose to vote for whichever main party matches their goals and ideals are called small-l libertarians (l) or "philosophical libertarians" because they are more willing to compromise to advance individual liberty. In the ], a few "small-l libertarians" advocated ] for President in the primaries because of his belief in gun rights and his moderate approval of free trade, and their fear of John Kerry and George Bush as even worse political choices. Several philosophical libertarians voted for George W. Bush fearing John Kerry would be even less in favor of free trade than Bush; and others voted for Bush because of the Republican party's claim to be the party of smaller government. A smaller minority of philosophical libertarians voted for John Kerry, mostly as a protest vote against Bush, because of Bush's failure to restrain federal spending. A greater number of philosophical libertarians either abstained from voting entirely (typically in their belief that the Libertarian Candidate for 2004 was poorly-chosen), or voted for the 2004 Libertarian Presidential Candidate, ], anyway, believing both major party choices in 2004 were opposed to fundamental Libertarian tenets. | |||

| *''']''': Some libertarians believe that property rights in ideas (and other intangibles) should be identical to property rights in physical goods, as they see both justified by natural rights. Others justify ] for utilitarian reasons. They argue that intellectual property rights are required to maximize innovation. Still others believe that "intellectual property" is a euphemism for ] and altogether. | |||

| *''']''': Libertarians of the Natural Law variety generally support freedom of movement, but other libertarians argue that open borders amount to legalized trespassing. The debate often centers on self-ownership of bodies and whether we have the freedom to hire anyone without the federal government's permission. Other times, the debate centers on immigrants abusing tax-funded government resources. "Consequentialist libertarians" may decide the issue in terms of what is best for the economy. Ideally for a libertarian, there would be minimal government involvement in various social programs, thus virtually no increased tax burden of immigration. | |||

| *''']''': A controversy is the role of the state in regulating ], if it is in fact unethical. In the United States, some on both sides of this debate agree that this should be settled by the several states instead of the national central government, thereby invalidating '']'' on grounds that it was a centralizing decision by the national government violating traditional state self-police powers. American libertarians who are not states-rights advocates, on the other hand, prefer for the issue to be settled at whatever level of government will reach the best decision. Although considered to be a minority of libertarians, a significant number of libertarians (including many in the ]) view abortion to be an initiation of force against the fetus and therefore wrong, while other libertarians view the fetus's early stages of development to be under the control of the female or individual(s) bearing responsibility for its development. Some anarcho-capitalists, including ] and ] oppose abortion and the centralizing Roe v. Wade decision. | |||

| *''']''': Some libertarians support the ] on ] or ] grounds. Others see it as an excessive abuse of state power. Many consitutionalist libertarians disavow the death penalty for its irreversible nature, as well as its perceived conflict with the Bill of Rights' ban on "cruel and unusual punishment". | |||

| *''']''': Most libertarians oppose and are suspicious of government intervention in the affairs of other countries, especially violent intervention. Others (such as those influenced by Objectivism) argue that intervention is not unethical when a foreign government is abusing the rights of its citizens but whether a nation should intervene depends on its own self-interest. Libertarians advocating foreign intervention are typically known as "Liberventionists". | |||

| *''']''': Most libertarians feel that adults have a right to choose their own lifestyle or sexual preference, provided that such expression does not trample on the same freedom of other people to choose their own sexual preference or religious freedom. Yet, there has been some debate among libertarians as to how to respond to the issue homosexuality in armed forces and gay marriage. The controversy arises virtually entirely from the current involvement of the State in heterosexual marriage. The philosophically pure libertarian answer is to treat all marriage contracts as legal contracts only, and to require that the terms of the marriage are spelled out clearly in the contract, allowing any number of legal adults to marry under any conditions that are legally enforceable, thus ending the implicit government-endorsement of all marriage contracts, including heterosexual ones. If the state no longer endorses only certain marriages as legitimate, there is no inequality, and gays, lesbians, polygamists, etc... can all draw up their own private legal contracts, just the same as heterosexuals could. The controversy arises from the fact that the State assumes that heterosexuals who did not draw up pre-nuptual agreements entered into a commonly recognized Christian ritual union that entitles the united parties to the use of the State's legal system as a means of filing a record of their marriage and of resolving disputes. This system is widely used by heterosexuals who have not prepared for the likelihood of divorce and later contractual dispute. Although the system is currently thus flawed, many gays who wish to marry want the same ability to turn to the state in hopes that the same government assumptions of tax-funded contract protection that occasionally benefits heterosexuals. The dilemma for most libertarians arises from the fact that a currently unjust situation is popular. Heterosexuals currently have tax-funded protection and the assumption of enforceable contract resolution for their marriage contracts. Homosexuals often desire inclusion in this flawed system. Libertarians then, are caught in the situation of trying to expand an unjust system to grant incorrectly-perceived benefits, or to deny certain parties membership within that unjust system. Many libertarians advocate the concept that there can be no such thing as a just separation of people into differing status groups under the law, so the current definition of marriage must include all those who wish to marry, with the later goal of eliminating this increased role of government in marriage entirely. It is thus the consistent view amongst all libertarians that the best resolution of inequalities under the law for gays would best be resolved by eliminating all state involvement in marriage (for heterosexuals, gays, polygamists, etc...), rendering every living human exactly equal under the law. | |||

| *''']''': Libertarians may disagree over what to do in absence of a will or contract in the event of death, and over posthumous property rights. In the event of a contract, the contract is enforced according to the property owner's wishes. Typically, libertarians believe that any unwilled property goes to remaining living relatives, and ideally, none of the property goes to the government in such a case. Many libertarians advocate the establishments of trusts to avoid taxation of property at the time of death. | |||

| *''']''': Some libertarians, (such as ] and ]) believe that environmental damage is a result of ] and believe that private ownership of all natural resources will result in a better environment, as a private owner of property will have more incentive to ensure the longer term value of the property. Others, such as ], believe that such resources (especially land) cannot be considered property. | |||

| The Libertarian Party approach to these issues is to say the focus is misplaced. Under the LP members agreed that party documents and officials must focus on voluntary solutions and not favor any particular mode, be it minarchism or anything else. On social issues the Platform focuses on voluntary alternatives and civil institutions, not coercive government, as the correct problems-solving entity. Those concerned about defense and immigration should look to the voluntary actions underway encouraged or performed by the Libertarian Party or allied movements. The correct solution to foreign woes is more Libertarian policies and presumably Libertarians in all countries. | |||

| == Criticism of libertarianism == | |||

| {{main|Criticism of libertarianism}} | |||

| Critics of libertarianism from both the ] and the ] claim that libertarian ideas about individual economic and social freedom are contradictory, untenable or undesirable. Critics from the left tend to focus on the economic consequences, claiming that perfectly ], or ] ], undermines individual freedom for many people by creating ], ], and lack of accountability for the most powerful. Criticism of libertarianism from the right tends to focus on issues of ] and personal morality, claiming that the extensive personal freedoms promoted by libertarians encourage unhealthy and immoral behavior and undermine religion. Libertarians mindful of such criticisms claim that personal responsibility, private ], and the voluntary exchange of goods and ideas are all consistent manifestations of an ] approach to liberty, and provide both a more effective and more ethical way to prosperity and peaceful coexistence. They often argue that in a truly capitalistic society, even the poorest would end up better off as a result of faster overall ] - which they believe likely to occur with lower taxes and less ]. | |||

| == Footnotes== | |||

| <references/> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{wiktionary|libertarian}} | |||

| <div style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| </div> | |||

| ===Libertarian ]s=== | |||

| <div style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| </div> | |||

| ==References== | |||

| <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| * {{cite web| authorlink = Walter Block | last = Block | first = Walter | url = http://www.lewrockwell.com/block/block26.html | title = The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism | date = ] ] | accessdate = 2005-06-30}} | |||

| * {{cite news| first = Brooke Shelbey | last = Biggs | title = You're Not the Boss of Me! | work = ] | date = ] ]}} | |||

| * {{cite web| authorlink = David Boaz | last = Boaz | first = David | url = http://www.libertarianism.org/ex-3.html | title = Chapter 1: A Note on Labels: Why "Libertarian"? | work = Libertarianism | accessdate = 2005-06-21}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Cohen | first = G.A. | title = Self-ownership, Freedom and Equality | location = Cambridge, UK | publisher = Cambridge University Press | year = 1995}} | |||

| * {{cite news| last = Cleveland | first = Paul | coauthors = Stevenson, Brian | title = Individual Responsibility and Economic Well-Being | work = The Freeman | date = August 1995}} | |||

| * {{cite journal| last = Cubeddu | first = Raimondo | url = http://www.univ.trieste.it/~etica/2003_2/ | title = Prospettive del Libertarismo (preface) | journal = Etica & Politica | volume = 5 | issue = 2 | year = 2003}} | |||

| * Franzen, Don. ''Los Angeles Times Book Review Desk'', review of "Neither Left Nor Right". January 19, 1997. Franzen states that "Murray and Boaz share the political philosophy of libertarianism, which upholds individual liberty--both economic and personal--and advocates a government limited, with few exceptions, to protecting individual rights and restraining the use of force and fraud." (). MSN '']''<nowiki>'</nowiki>s defines it as a "political philosophy" (Both references retrieved June 24, 2005). The ''Encyclopedia Britannica'' defines Libertarianism as "Political philosophy that stresses personal liberty." (, accessed June 29, 2005) | |||

| * {{cite book| authorlink = Shannon Leigh Fallon | last = Fallon | first = Shannon | title = The Bill of Rights: What It Is, What It Means, and How It's Been Misused | id = ISBN 1-880741-25-3}} | |||

| * {{cite journal| last = Friedman | first = Jeffrey | title = What's Wrong With Libertarianism| journal = Critical Review | volume = 11 | issue = 3 | month = Summer | year = 1997 | url = http://www.tomgpalmer.com/papers/friedman-whatswrong-cr-v11n3.pdf | format = {{PDFlink}}}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Friedman | first = Milton | chapterurl = http://www.druglibrary.org/special/friedman/socialist.htm | chapter = The Drug War as a Socialist Enterprise | title = Friedman & Szasz on Liberty and Drugs | editor = Arnold S. Trebach and Kevin B. Zeese (eds.) | location = Washington, D.C. | publisher = The Drug Policy Foundation | year = 1992}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Gillespie | first = Nick | url = http://www.reason.com/0503/ed.ng.editors.shtml | title = Rand Redux | work = Reason | date = March 2005}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Goldberg | first = Jonah | url = http://www.nationalreview.com/goldberg/goldberg121201.shtml | title = Freedom Kills | work = ] | date = ] ]}} | |||

| * {{cite book| editor = Harwood, Sterling (ed.) | title = Business as Ethical and Business as Usual | location = Belmont, CA | publisher = Wadsworth Publishing}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Hayek | first = F.A. | title = Why I am not a Conservative | publisher = ] Press | year = 1960 | url = http://hem.passagen.se/nicb/cons.htm}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Hospers | first = John | title = Libertarianism | location = Santa Barbara, CA | publisher = Reason Press | year = 1971}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Hospers | first = John | chapter = Arguments for Libertarianism | editor = Harwood, Sterling (ed.) | title = Business as Ethical and Business as Usual | location = Belmont, CA | publisher = Wadsworth Publishing}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Huben | first = Michael | url = http://world.std.com/~mhuben/faq.html#nolan | title = The World's Smallest Political Quiz. (Nolan Test) | work = A Non-Libertarian FAQ | date = ] ] | accessdate = 2006-07-10}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Kangas | first = Steve | url = http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-chichile.htm | title = Chile: The Laboratory Test | work = Liberalism Resurgent | accessdate = 2006-07-10}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = LaFollette | first = Hugh | chapter = Why Libertarianism is Mistaken | editor = Harwood, Sterling (ed.) | title = Business as Ethical and Business as Usual | location = Belmont, CA | publisher = Wadsworth Publishing | pages = 58–66}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last = Lester| first = J.C. | title = Escape from Leviathan: Liberty, Welfare and Anarchy Reconciled| location = Basingstoke, UK/New York, USA | publisher = Macmillan/St Martin's Press| year = 2000}} | |||

| * {{cite journal| last = Lester| first = J.C.| url = http://www.la-articles.org.uk/wwwl.pdf| title = What's Wrong with "What's Wrong with Libertarianism": A reply to Jeffrey Friedman| journal = Liberty| issue = August | year = 2003}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Levy | first = Jacob | url = http://volokh.com/2003_03_16_volokh_archive.html#200013465 | title = Self-Criticism | work = ] | date = ] ] | accessdate = 2006-07-10}} | |||

| * {{cite web| last = Machan | first = Tibor R. | url = http://www.liberalia.com/htm/tm_minarchists_anarchists.htm | title = Revisiting Anarchism and Government | accessdate = 2006-07-10}} | |||