| Revision as of 17:12, 16 October 2018 editShellwood (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers406,520 editsm Reverted edits by 80.43.209.138 (talk): not providing a reliable source (WP:CITE, WP:RS) (HG) (3.4.4)Tags: Huggle Rollback← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:29, 25 October 2018 edit undoRchristo100 (talk | contribs)13 editsm →Living conditionsNext edit → | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

| ==Living conditions== | ==Living conditions== | ||

| The Korean word for "homosexual" is ''dongseongaeja'' ({{ko-hhrm|hangul=동성애자|hanja=同性愛者}}, "same-sex lover"). A less politically correct term is ''dongseongyeonaeja'' (Hangul: 동성연애자; Hanja: 同性戀愛者). South Korean homosexuals, however, make frequent use of the term ''ibanin'' (Hangul: 이반인; Hanja: 異般人 also 二般人) which can be translated as "different type person", and is usually shortened to ''iban'' (Hangul: 이반; Hanja: 異般).<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070918112946/http://kirikiri.org/bbs/zboard.php?id=fag_1&page=1&sn1=&divpage=1&sn=off&ss=on&sc=on&select_arrange=headnum&desc=asc&no=15 |date=18 September 2007 }}; dead link as of 2009-01-17</ref> The word is a direct play on the word ''ilban-in'' (Hangul: 일반인; Hanja: 一般人) meaning "normal person" or "ordinary person". In addition, ] to describe LGBTQ people. These words are simple transliterations of English words into ]: lesbian is ''lejeubieon'' or ''yeoseongae'' (Hangul: 레즈비언 or 여성애; Hanja: 女性愛), gay is ''gei'' or ''namseongae'' (Hangul: 게이 or 남성애; Hanja: 男性愛), queer is ''kuieo'' (Hangul: 퀴어), transgender is ''teuraenseujendeo'' (Hangul: 트랜스젠더), and bisexual is "yangseongaeja" (Hangul: 양성애자; Hanja: 兩性愛者).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dcollection.snu.ac.kr:80/jsp/common/DcLoOrgPer.jsp?sItemId=000000013281 |title=Queer Identity and Sexuality in South Korea: A Critical Analysis via Male Bisexuality |publisher=Seoul National University |date= |accessdate=2013-08-01}}</ref> | The Korean word for "homosexual" is ''dongseongaeja'' ({{ko-hhrm|hangul=동성애자|hanja=同性愛者}}, "same-sex lover"). A less politically correct term is ''dongseongyeonaeja'' (Hangul: 동성연애자; Hanja: 同性戀愛者). South Korean homosexuals, however, make frequent use of the term ''ibanin'' (Hangul: 이반인; Hanja: 異般人 also 二般人) which can be translated as "different type person", and is usually shortened to ''iban'' (Hangul: 이반; Hanja: 異般).<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070918112946/http://kirikiri.org/bbs/zboard.php?id=fag_1&page=1&sn1=&divpage=1&sn=off&ss=on&sc=on&select_arrange=headnum&desc=asc&no=15 |date=18 September 2007 }}; dead link as of 2009-01-17</ref> The word is a direct play on the word ''ilban-in'' (Hangul: 일반인; Hanja: 一般人) meaning "normal person" or "ordinary person". In addition, ] to describe LGBTQ people. These words are simple transliterations of English words into ]: lesbian is ''lejeubieon'' or ''yeoseongae'' (Hangul: 레즈비언 or 여성애; Hanja: 女性愛), gay is ''gei'' or ''namseongae'' (Hangul: 게이 or 남성애; Hanja: 男性愛), queer is ''kuieo'' (Hangul: 퀴어), transgender is ''teuraenseujendeo'' (Hangul: 트랜스젠더), and bisexual is "yangseongaeja" (Hangul: 양성애자; Hanja: 兩性愛者). As of 2013, male bisexuality has only been studied once in the country.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dcollection.snu.ac.kr:80/jsp/common/DcLoOrgPer.jsp?sItemId=000000013281 |title=Queer Identity and Sexuality in South Korea: A Critical Analysis via Male Bisexuality |publisher=Seoul National University |date= |accessdate=2013-08-01}}</ref> | ||

| Homosexuality remains quite ] in South Korean society. This lack of visibility is also reflected in the low profile maintained by the few gay clubs in South Korea. There are a few in metropolitan areas, mostly in the foreign sector of ] (especially in the section known as "Homo-hill").<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.utopia-asia.com/korseoul.htm |title=Gay Seoul Gay Resources and Travel Tips in Korea by Utopia |publisher=Utopia-asia.com |date= |accessdate=2011-01-20}}</ref> However, ] has been known to cater to non-Western clientele and has various gay-friendly shops, cafés, and gay-focused NGOs. A recent 2017 study insinuated the growth of a "gay life style" community in Jong-no, a popular area in Seoul, where LGBT individuals feel safe in semi-heteronomative places.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002205343 |title=Compromised Sexual Territoriality Under Reflexive Cosmopolitanism|publisher=한국지역지리학회지 제23권 제1호, 2017.2, 23–46 (24 pages)}}</ref> Though the study only looked at a well-known café, the famous Gay Bean, there are many other places in the Jong-no area that are considered straight but are growing increasingly welcoming of non-straight individuals. | Homosexuality remains quite ] in South Korean society. This lack of visibility is also reflected in the low profile maintained by the few gay clubs in South Korea. There are a few in metropolitan areas, mostly in the foreign sector of ] (especially in the section known as "Homo-hill").<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.utopia-asia.com/korseoul.htm |title=Gay Seoul Gay Resources and Travel Tips in Korea by Utopia |publisher=Utopia-asia.com |date= |accessdate=2011-01-20}}</ref> However, ] has been known to cater to non-Western clientele and has various gay-friendly shops, cafés, and gay-focused NGOs. A recent 2017 study insinuated the growth of a "gay life style" community in Jong-no, a popular area in Seoul, where LGBT individuals feel safe in semi-heteronomative places.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002205343 |title=Compromised Sexual Territoriality Under Reflexive Cosmopolitanism|publisher=한국지역지리학회지 제23권 제1호, 2017.2, 23–46 (24 pages)}}</ref> Though the study only looked at a well-known café, the famous Gay Bean, there are many other places in the Jong-no area that are considered straight but are growing increasingly welcoming of non-straight individuals. | ||

Revision as of 04:29, 25 October 2018

| LGBTQ rights in South Korea | |

|---|---|

South Korea South Korea | |

| Status | No laws against homosexuality in recorded Korean history |

| Gender identity | Transgender persons allowed to change legal sex |

| Military | Homosexuality not condoned by military. All male citizens are conscripted into service and subject to military's policies regarding homosexuality (see below) |

| Discrimination protections | None |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender ∙ Queer |

Overview

|

| Aspects |

| Opposition |

| Organizations |

| Politics |

| Timeline |

| Related |

|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in South Korea face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Male and female same-sex sexual activity is legal in South Korea, but marriage or other forms of legal partnership are not available to same-sex partners.

Homosexuality in South Korea is not specifically mentioned in either the South Korean Constitution or in the Civil Penal Code. Article 31 of the National Human Rights Commission Act states that "no individual is to be discriminated against on the basis of his or her sexual orientation". However, Article 92 of the Military Penal Code, which is currently under a legal challenge, singles out sexual relations between members of the same sex as "sexual harassment", punishable by a maximum of one year in prison. The Military Penal Code does not make a distinction between consensual and non-consensual crimes and names consensual intercourse between homosexual adults as "reciprocal rape" (Korean: 상호강간; Hanja: 相互强姦). But a military court ruled in 2010 that this law is illegal, saying that homosexuality is a strictly personal issue. This ruling was appealed to South Korea's Constitutional Court, which has not yet made a decision.

Transgender people are allowed to undergo sex reassignment surgery in South Korea after the age of 20, and can change their gender information on official documents. Harisu is South Korea's first transgender entertainer, and in 2002 became only the second person in South Korea to legally change gender.

General awareness of homosexuality remained low among the Korean public until recently, with increased awareness and debate coming to the issue, as well as gay-themed entertainment in mass media and recognizable figures and celebrities, such as Hong Seok-cheon, coming out in public. But gay and lesbian Koreans still face difficulties at home and work, and many prefer not to reveal their identities to their family, friends or co-workers.

In August 2017, the Supreme Court ordered the Government to allow "Beyond the Rainbow", an LGBT rights foundation, to register as a charity with the Ministry of Justice. Without official registration, the foundation was unable to receive tax-deductible donations and operate in full compliance with the law. Additionally, the South Korean Government voted in favor of a 2014 United Nations resolution aimed at overcoming discrimination against LGBT people.

History

Main article: LGBT history in South KoreaCovering all sources, homosexuality has never been illegal in South Korea.

Although there is very little mention of homosexuality in Korean literature or traditional historical accounts, several members of nobility and Buddhist monks have been known to either profess their attraction to members of the same sex or else be actively involved with them.

During the Silla Dynasty, several noble men and women are known to have engaged in homosexual activity and express their love for a person of the same sex. Among these are King Hyegong and King Sejong's daughter-in-law who slept with her maid. In addition, the hwarang (Hangul: 화랑; Hanja: 花郞), also known as the Flowering Knights or the Flowering Boys, were an elite group of male Silla warriors, famous for their homoeroticism and femininity. The Samguk yusa, a collection of Korean legends, folktales and historical accounts, contains verses that reveal the homosexual nature of the hwarang.

During the Goryeo Dynasty, King Mokjong (980-1009) and King Gongmin (1325–1374) are both on record as having kept several wonchung ("male lovers") in their courts as "little-brother attendants" (chajewhi) who served as sexual partners. After the death of his wife, King Gongmin even went so far as to create a ministry whose sole purpose was to seek out and recruit young men from all over the country to serve in his court. Others including King Chungseon had long-term relationships with men. Those who were in same-sex relationships were referred to as yongyang jichong, whose translation has been subject to argument, but is generally viewed as meaning the "dragon and the sun".

In the Joseon Era before the Japanese annexation, there were travelling theater groups known as namsandang which included underaged males called midong (beautiful boys). The troupes provided "various types of entertainment, including band music, song, masked dance, circus, and puppet plays," sometimes with graphic representations of same-sex intercourse. The namsandang were further separated in two groups; the "butch" members (숫동모, sutdongmo) and the "queens" (여동모, yeodongmo, or 암동모, amdongmo).

The spread of Neo-Confucianism in South Korea shaped the moral system, the way of life and social relations of Korean society. Neo-Confucianism emphasises strict obedience to the social order and the family unit, which refers to a husband and wife. Homosexuality and same-sex relationships were viewed as disturbing this system and thus were perceived as "deviant" or "immoral". Since the 1910s, Neo-Confucianism has lost a lot of influence, though still today Confucian ideas and practices significantly define South Korean culture and society.

Homosexuality was officially declassified as "harmful and obscene" in 2003.

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Main article: Recognition of same-sex unions in South KoreaSame-sex marriages and civil unions are not legally recognized in South Korea.

In October 2014, some members of the Democratic Party introduced to the National Assembly a bill to legalize same-sex partnerships.

In July 2015, actor Kim Jho Gwangsoo and his partner, Kim Seung-Hwan, filed a lawsuit seeking legal status for their marriage. The lawsuit was rejected by the Seoul Western District Court in May 2016 and by an appeals court in December 2016. The lawsuit is currently before the Supreme Court.

In January 2018, LGBT activists expressed hopes that a draft constitution, which had to be ready by June 2018, would include the legalisation of same-sex marriage. Amendments to the South Korean Constitution require a two-thirds majority in Parliament. Talks on the new Constitution have failed, however.

Discrimination protections

The National Human Rights Commission Act, enacted in 2001, established the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK). Under South Korean law, the NHRCK is an independent commission for protecting, advocating and promoting human rights. The National Human Rights Commission Act explicitly includes sexual orientation as an anti-discrimination ground. When discriminatory acts are found to have occurred, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea may conduct investigations on such acts and recommend non-binding relief measures, disciplinary actions or report them to the authorities.

South Korea's anti-discrimination law, however, does not prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2013, a bill to include sexual orientation, religion and political ideology to the country's anti-discrimination law was introduced. It received fierce opposition from conservative groups. A 2014 poll found that 85% of South Koreans believed gay people should be protected from discrimination. According to a more recent poll, conducted in 2017 by Gallup Korea, 90% of South Koreans said they supported equal employment opportunities for LGBT people.

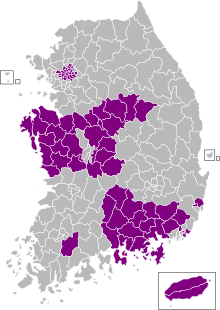

Currently, 14 local governments in South Korea have enacted anti-discrimination laws that include sexual orientation. This includes four first-level subdivisions: South Gyeongsang Province, Seoul, Jeju Province and North Chungcheong Province.

South Gyeongsang Province enacted an anti-discrimination law in March 2010. The law states that "citizens shall not be discriminated, without reasonable grounds, on the grounds of sex, religion, disability, age, social status, region of origin, state of origin, ethnic origin, physical condition such as appearance, medical history, marital status, political opinion, and sexual orientation".

Seoul has banned discrimination on the grounds mentioned in the National Human Rights Commission Act since September 2012. The passage of the law received opposition from conservative groups, who have called for its repeal, organising public campaigns, in which they called gays "beasts", and public marches in favour of the law's repeal. Several opponents argue that the law constitutes "heresy" and "encourage homosexuality" because it includes religion and sexual orientation as grounds of non-discrimination.

Similarly, both Jeju Province and North Chungcheong Province passed laws in October 2015 banning discrimination on the grounds mentioned in the National Human Rights Commission Act.

Several second-level jurisdictions have also enacted anti-discrimination laws that cover sexual orientation. These are:

- Dong District, Daejeon (April 2015)

- Nam District, Busan (May 2011)

- Buk District, Busan (March 2012)

- Suyeong District, Busan (December 2010)

- Haeundae District, Busan (July 2015)

- Yeonje District, Busan (November 2010)

- Eunpyeong District, Seoul (October 2015)

- Buk District, Ulsan (January 2011)

- Jung District, Ulsan (April 2013)

- Hwasun County (December 2017)

Anti-bullying and student ordinances

Gyeonggi Province banned bullying against students on the basis of their sexual orientation in October 2010. Gwangju followed suit in October 2011, and Seoul in January 2012. Seoul's ordinance on the protection of children and youth also includes gender identity, thereby protecting transgender students from discrimination. North Jeolla Province enacted an ordinance banning bullying against "sexual minorities" in January 2013.

South Gyeongsang Province is expected to enact a similar ordinance by the end of 2018, and Incheon has also promised to enact one. There is also growing pressure in Busan for the passage of a similar law.

Other laws

In addition, other various laws have protections for "sexual minorities". Police officers and Coast Guard personnel are forbidden from outing an LGBT person against their own will.

In November 2017, the city of Geoje passed a media law prohibiting broadcasting agencies from spreading information encouraging discrimination against "sexual minorities".

Constitutional rights

The Constitution of South Korea prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, religion and social status. According to the Ministry of Justice, the term "social status" includes LGBT people. However, there are no remedies for LGBT victims of discrimination nor are these "protections" enforced.

Military service

Military service is mandatory for all male citizens in South Korea. Enlistees are drafted through the Military Manpower Administration (MMA; Template:Lang-ko) which administers a "psychology test" at the time of enlistment that includes several questions regarding the enlistee's sexual preferences. Homosexual military members in active duty are categorized as having a "personality disorder" or "behavioural disability" and can either be institutionalized or dishonorably discharged. A lawsuit is currently before to South Korean Constitutional Court. In 2017, Amnesty International accused the military of engaging in a "gay witch hunt" to expose and punish gay personnel, including sentencing a gay soldier to six months imprisonment for having consensual sex with another gay soldier in a private place.

Transgender rights

The Supreme Court of South Korea has ruled that in order for a person to be eligible for a sex change operation they must be over 20 years of age, single and without children. In the case of MTF (Male-to-Female) gender reassignment operations, the person must prove issues related to draft resolved by either serving or being exempted. On 22 June 2006, however, the Supreme Court ruled that transgender individuals who had undergone successful sex reassignment surgery have the right to declare their new sex in all legal documents. This includes the right to request a correction of their gender-on-file in all public and government records such as the census registry. In March 2013, the Seoul Western District Court ruled that five female-to-male transgender individuals can be registered as male without undergoing sex reassignment surgery. On 16 February 2017, the Cheongju District Court ruled that a male-to-female transgender individual could be registered as a female without undergoing surgery.

Conversion therapy

According to a 2016 survey, 16.1% of LGBT people who had come out were recommended to undergo conversion therapy. Of these, 65.4% said it had a harmful impact on their lives, with 94% experiencing psychological trauma.

Blood donation

South Korea forbids people who have had sex within the past one year to donate blood. These rules apply equally to straight, gay and bisexual people.

Living conditions

The Korean word for "homosexual" is dongseongaeja (Korean: 동성애자; Hanja: 同性愛者, "same-sex lover"). A less politically correct term is dongseongyeonaeja (Hangul: 동성연애자; Hanja: 同性戀愛者). South Korean homosexuals, however, make frequent use of the term ibanin (Hangul: 이반인; Hanja: 異般人 also 二般人) which can be translated as "different type person", and is usually shortened to iban (Hangul: 이반; Hanja: 異般). The word is a direct play on the word ilban-in (Hangul: 일반인; Hanja: 一般人) meaning "normal person" or "ordinary person". In addition, English loanwords are used in South Korea to describe LGBTQ people. These words are simple transliterations of English words into hangul: lesbian is lejeubieon or yeoseongae (Hangul: 레즈비언 or 여성애; Hanja: 女性愛), gay is gei or namseongae (Hangul: 게이 or 남성애; Hanja: 男性愛), queer is kuieo (Hangul: 퀴어), transgender is teuraenseujendeo (Hangul: 트랜스젠더), and bisexual is "yangseongaeja" (Hangul: 양성애자; Hanja: 兩性愛者). As of 2013, male bisexuality has only been studied once in the country.

Homosexuality remains quite taboo in South Korean society. This lack of visibility is also reflected in the low profile maintained by the few gay clubs in South Korea. There are a few in metropolitan areas, mostly in the foreign sector of Itaewon (especially in the section known as "Homo-hill"). However, Jong-no has been known to cater to non-Western clientele and has various gay-friendly shops, cafés, and gay-focused NGOs. A recent 2017 study insinuated the growth of a "gay life style" community in Jong-no, a popular area in Seoul, where LGBT individuals feel safe in semi-heteronomative places. Though the study only looked at a well-known café, the famous Gay Bean, there are many other places in the Jong-no area that are considered straight but are growing increasingly welcoming of non-straight individuals.

In recent years, the combination of taboo, consumer capitalism, and gay-led gentrification (the so-called "gaytrification effect") of the Itaewon area has pushed new gay commercialization outside of Itaewon, while isolating those places remaining.

Opposition to LGBT rights comes mostly from Christian sectors of the country (especially Protestants). In recent years, in part due to growing support for homosexuality and same-sex relationships from South Korean society at large, conservative groups have organised public events and marches against LGBT rights, as well counter-protests to pride parades, usually with signs urging LGBT people to "repent from their sins". These marches have been attended by thousands and by various politicians.

Media

South Korea's first gay-themed magazine, Buddy, launched in 1998, and several popular gay-themed commercials have also aired.

Paving the way for television was the 2005 South Korean film The King and the Clown, a gay-themed movie based on a court affair between a king and his male jester. The movie became the highest grossing in Korean film history, surpassing both Silmido and Taegukgi. The Korean title for The King and the Clown is "왕의 남자" which translates as "The King's Man" with the implication that it refers to the man as being the King's lover. Other recent movies include the 2008 film A Frozen Flower (Template:Lang-ko) and No Regret (Template:Lang-ko) by celebrated director Leesong hee-il (Template:Lang-ko), which starred at the 2006 Busan International Film Festival.

Mainstream Korean television shows have begun to feature gay characters and themes. In 2010, the soap opera Life Is Beautiful (Template:Lang-ko) premiered on SBS broadcast TV, becoming the first prime-time drama to explore a gay male couple's relationship as their unwitting families set them up on dates with women. That same year, Personal Taste (Template:Lang-ko, also "Personal Preference") was broadcast on MBC and revolved around a straight man who pretends to be gay to become a woman's roommate. Before these was Coming Out, which debuted on cable channel tvN in late night in 2008, in which a gay actor and straight actress counseled gays with publicly acknowledging their sexual orientation.

Openly LGBT entertainment figures include model and actress Harisu, a trans woman who makes frequent appearances on television. Actor Hong Seok-cheon, after coming out in 2000 and being fired from his job, has since returned to his acting career. He has appeared in several debate programs in support of gay rights.

Popular actor Kim Ji-hoo, who was openly gay, hanged himself on 8 October 2008. Police attributed his suicide to public prejudice against homosexuality.

"The Daughters of Bilitis" a KBS Drama Special about the lives of lesbian women, aired on 7 August 2011. Immediately after it aired, internet message boards lit up with outraged protesters who threatened to boycott the network. The production crew eventually shut down the online re-run service four days after the broadcast.

"XY She," a KBS Joy cable talk show about MTF transgender individuals, was virtually cancelled after its first episode due to public opposition. The network cited concern over attacks on MCs and other cast-members as the official reason for cancellation.

In 2013, movie director Kim Jho Kwang-soo and his partner Kim Seung-hwan became the first South Korean gay couple to publicly wed, although it was not a legally recognized marriage.

In 2016, a Christian broadcasting company was sanctioned by the Korea Communications Standards Commission for broadcasting an anti-LGBTI interview on a radio program, in which the interviewee claimed that, if an "anti-discrimination law for LGBTI people" is passed, "paedophilia, bestiality, etc. will be legalized” and that South Korea "will become stricken with unspeakable diseases such as AIDS".

In 2017, the film Method was released. The film talks about a gay relationship between an actor and an idol.

In January 2018, singer Holland became the first openly gay K-pop idol in South Korea to debut, releasing his song "Neverland".

Pride parades

In July 2017, an estimated 85,000 people (according to the organizers) marched in the streets of Seoul in support of LGBT rights. The event was first held in 2000 (when only 50 attended) and turnout has increased every year since then. In 2016, there were 50,000 attendees.

The 2018 Seoul Pride parade was attended by an estimated 120,000 people.

Daegu has been holding annual pride marches since 2009, and Busan held its first pride event on September 23, 2017. Gwangju and Jeju also held their first LGBT events in 2017. Gwangju's was a counter-protest to an anti-LGBT rally. The city organised its first official pride event the following year. Other cities, including Incheon and Jeonju, held their first pride events in 2018. Incheon’s LGBT event ended in violence after about 1,000 Christian protestors began violently attacking the participants.

Public opinion

South Koreans have become significantly more accepting of homosexuality and LGBT rights in 2010 and the onward decade, even if conservative attitudes remain dominant. A 2013 Gallup poll found that 39% of people believed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared to only 18% who held this view in 2007. South Korea recorded the most significant shift towards greater acceptance of homosexuality among the 39 countries surveyed worldwide. Significantly, there was a very large age gap on this issue: in 2013, 71% of South Koreans aged between 18 and 29 believed that homosexuality should be accepted, compared to only 16% of South Koreans aged 50 and over.

In April 2013, a Gallup poll, which was commissioned by a conservative Christian group, found that 25% of South Koreans supported same-sex marriage, while 67% opposed it and 8% did not know or refused to answer. However, a May 2013 Ipsos poll found that 26% of respondents were in favor of same-sex marriage and another 31% supported other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

A poll in December 2017 conducted by Gallup for MBC and the Speaker of the National Assembly reported that 41% of South Koreans thought that same-sex marriage should be allowed, 52% were against it.

Public support for same-sex marriage is growing rapidly. In 2010, 30.5% and 20.7% of South Koreans in their 20s and 30s, respectively, supported the legalization of same-sex marriages. In 2014, these numbers had almost doubled to 60.2% and 40.4%. Support among people over 60, however, remained relatively unchanged (14.4% to 14.5%).

Politics

Political support for LGBT rights is limited in South Korea due to the significant lobbying power exerted by conservative Christian groups. Support for LGBT rights is limited even in the nominally progressive Democratic Party of Korea and its leader, former human rights lawyer and South Korean President Moon Jae-in. During the 2017 presidential election, in which he emerged victorious, Moon stated that he opposed homosexuality, and that gay soldiers could undermine the Korean military. Moon faced criticism from gay rights advocates for his inconsistent position on minority rights, given that he was prepared to backtrack on previous support for civil unions and sacrifice LGBT rights in order to win votes from conservative Christian voters. Moon later said that he opposed same-sex marriage while also opposing discrimination against homosexual people. Only one of the 14 presidential candidates in 2017, the Justice Party's Sim Sang-jung, expressed clear support for LGBT rights and introducing discrimination protections for LGBT people.

Censorship issues

Main article: Internet censorship in South KoreaThe Government of South Korea practiced censorship of gay content websites from 2001 to 2003, through its Information and Communications Ethics Committee (Hangul: 정보통신윤리위원회), an official organ of the Ministry of Information and Communication. That practice has since been reversed.

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (13) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Conversion therapy banned | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSM allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- ^ "Will homosexuality be accepted in barracks?". The Korea Times.

- "Being gay in South Korea". GayNZ.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Global Divide on Homosexuality". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- South Korea's 18th Queer festival starts today, but gay people still face discrimination and hate

- "South Korea: Supreme Court Affirms LGBT Rights". Human Rights Watch. 4 August 2017.

- "Government denies recognition to sexual minority rights group". The Hankyoreh. 4 May 2015.

- ^ Fact Sheek: LGBTQ Rights in South Korea

- "Korean Gay and Lesbian History". Utopia-asia.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- Homosexuality in ancient and modern Korea

- ^ South Korean University Students’ Attitudes toward Homosexuality and LGBT Issues

- Template:Ko icon 연애 말고, 결혼 말고, 동반자!

- S. Korean court rejects gay couple's appeal over same-sex marriage

- ^ Battle Over South Korea’s Constitutional Reform Focuses on LGBT Rights

- New speaker calls for parties' bill to revise Constitution by year-end

- ^ Human Rights Situation of LGBTI in South Korea 2016, SOGILAW Annual Report

- "Human Rights Committee Law of South Korea". National Assembly of South Korea. 19 May 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Home▹South Korean Anti-Discrimination Law Faces Conservative Pushback South Korean Anti-Discrimination Law Faces Conservative Pushback

- Template:Ko icon 한국갤럽 2014년 12월 12일(금) 공개 | 문의: 02-3702-2100(대표)/2571/2622

- ^ 2017년 한국 LGBTI 인권현황 (한국어/영어 합본)

- 서울 등 4곳 기존 조례와 큰 틀은 유사, 공청회 등 의견 수렴해 사회적 갈등 최소화 방침

- 도성훈 인천시교육감 공약 ‘학생인권조례 제정’ 추진…반대 여론 극

- ^ "For South Korea's LGBT Community, An Uphill Battle For Rights". NPR.org. National Public Radio. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "사람과사람 | People to People". Queerkorea.org. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "네이버 :: 페이지를 찾을 수 없습니다". Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Landmark legal ruling for South Korean transgenders". Hankyoreh. 16 March 2013.

- "성기 제거 안 해도 '남 → 여' 성별 정정 첫 허가". Kyunghyang Shinmun. 16 February 2017.

- ^ "자진배제가 무엇인가요?". 대한적십자사. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Kirikiri, the Lesbian Counseling Center in Korea Archived 18 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine; dead link as of 2009-01-17

- "Queer Identity and Sexuality in South Korea: A Critical Analysis via Male Bisexuality". Seoul National University. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Gay Seoul Gay Resources and Travel Tips in Korea by Utopia". Utopia-asia.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "Compromised Sexual Territoriality Under Reflexive Cosmopolitanism". 한국지역지리학회지 제23권 제1호, 2017.2, 23–46 (24 pages).

- The 'gaytrification' effect: why gay neighbourhoods are being priced out

- "Gaytrification and the Re-orienting of Sexual Peripheries". 현대사회와다문화 제6권 제1호, 2016.6, 90–119 (30 pages).

- "żÜąšŔÎŔť Ŕ§ÇŘ". Buddy79.com. 20 February 1998. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "네이버 :: 페이지를 찾을 수 없습니다". Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "네이버 영화 :: 영화와 처음 만나는 곳". Movie.naver.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "Saju and death of a transgender". The Korea Times.

- "Lee Min-ho to Star in New MBC Drama". The Korea Times. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- "Actor Hong Suk-Chun to Host 'Coming Out'". The Korea Times.

- Harisu Archived 9 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Hanson, Lisa (26 June 2004). "Gay community at crossroads". Korea Herald. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - 홍석천, 이성애자 마초 변신 "놀랍죠?" (in Korean). 7 September 2006. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "네이버 :: 페이지를 찾을 수 없습니다". Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Park, Si-soo. Gay Actor Found Dead in Apparent Suicide, The Korea Times, 8 October 2008. Retrieved on 4 November 2010.

- A Lesbian Drama Series Shocked South Korea

- SOUTH KOREA: KBS’ ‘XY THAT GIRL’ GETS ‘OUTED’!

- First South Korean Gay Couple To Publicly Wed Plans Challenge To Marriage Law

- Gay pride parade in Seoul draws record number

- "Seoul LGBT festival sees record numbers". Korea Joongang Daily. 16 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "[알림] 공식명칭을 변경합니다 ('퀴어문화축제조직위원회'➝'서울퀴어문화축제조직위원회', '퀴어문화축제'➝'서울퀴어문화축제')". SQCF. 15 March 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Queer fest badly delayed by violent anti-gay protests in Incheon

- "South Korea easing homophobic views on news of gay 'wedding'". NewsComAu. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- "Same-Sex Marriage". Ipsos. 7–21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "특집 여론조사…국민 59.7% "적폐청산 수사 계속해야"". MBC News. 26 December 2017.

- Over the Rainbow: Public Attitude Toward LGBT in South Korea The Asian Institute for Policy Studies

- Seo, Yoonjung; Fifield, Anna (3 June 2015). "South Korea, at behest of conservative Christians, bans LGBT march". Washington Post. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Tong-hyung, Kim (14 December 2012). "Moon bashes gay rights for church votes". Korea Times. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "South Korea's presidential hopeful Moon Jae In under fire over anti-gay comment". The Straits Times. 26 April 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "South Korean presidential front runner says he opposes homosexuality". South China Morning Post. 26 April 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Steger, Isabella (27 April 2017). "Being a progressive politician in Korea doesn't stop you from being homophobic". Quartz. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Tong-hyung, Kim (14 December 2012). "Moon bashes gay rights for church votes". Korea Times. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- "South Korean Presidential Hopeful Accused of Anti-Gay Comments". NBC News. NBC. 26 April 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Internet Censorship in South Korea". Information Policy.

- "자진배제신청(에이즈관련등록)". 대한적십자사. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

External links

- Buddy, Korean LGBT Magazine

- Chingusai, one of Korea's oldest gay men's organizations

- Korean Queer Culture Festival

- Korean Sexual-Minority Culture and Rights Center

- Solidarity for LGBT Human Rights of Korea

- RAinbowTEEN (Rateen), Youth Sexual Minority Community

- Lesbian Counseling Center in South Korea

Articles

- From 50 to 1,500: Korea Queer Culture Festival turns 10 by Matt Kelley Fridae.com. 16 June 2009

- South Korea's legal trans-formation by Matt Kelley and Mike Lee Fridae.com. 29 May 2009

- The deadly reality of South Korea's virtual world by Matt Kelley and Mike Lee Fridae.com. 17 October 2008

- 2 openly gay, trans South Korean actors commit suicide by Matt Kelley Fridae.com. 9 October 2008

- Seoul's spring forecast: More visibility for Korea's queers by Matt Kelley Fridae.com. 3 June 2008

- South Korea sees first openly gay politician, but challenges persist for the nation's lesbians by Matt Kelley Fridae.com. 18 March 2008

- Seoul policeman comes out, fights prejudice by News Editor Fridae.com. 11 January 2008

- Exclusion from non-discrimination bill mobilises Korea’s LGBT community by Matt Kelley Fridae.com. 23 November 2007

- 2007 Seoul LGBT film festival, 6 to 10 June by News Editor Fridae.com. 6 June 2007

| LGBT rights in Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |