| Revision as of 17:39, 31 August 2019 editEPIC (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers4,224 editsm Reverted edits by 190.102.3.151 (talk) to last version by ShellwoodTags: Rollback Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:00, 6 September 2019 edit undoStefanomione (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers52,898 edits add pictureTag: 2017 wikitext editorNext edit → | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| == Current day == | == Current day == | ||

| La Catedral remained deserted for several years. In 2007, a group of ] monks from the Benedictina Fraternidad Monastica Santa Gertrudis arrived at the site and transformed it. The monks came there because it is a great place for meditating and away from the city. They built a chapel, a library, a cafeteria, a guest-house for religious pilgrimages, workshops and a memorial to victims of the cartel in the prison. In addition, the monks hired laid-off people to help with the daily running of La Catedral. Considering their efforts of reconstructing the prison, the city ] then ceded the entire prison to those monks. <ref name=":0" /> | La Catedral remained deserted for several years. In 2007, a group of ] monks from the Benedictina Fraternidad Monastica Santa Gertrudis arrived at the site and transformed it. The monks came there because it is a great place for meditating and away from the city. They built a chapel, a library, a cafeteria, a guest-house for religious pilgrimages, workshops and a memorial to victims of the cartel in the prison. In addition, the monks hired laid-off people to help with the daily running of La Catedral. Considering their efforts of reconstructing the prison, the city ] then ceded the entire prison to those monks. <ref name=":0" /> | ||

| ==Pictures== | |||

| File:Helipad at La Catedral, the former Pablo Escobar prison overlooking the City of Medellin.jpg | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 02:00, 6 September 2019

This article is about the prison. For the musical piece, see Agustín Barrios.| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: Split into sections; formatting and wording according to MOS, proper citation of sources. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "La Catedral" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Medellín Cartel |

|---|

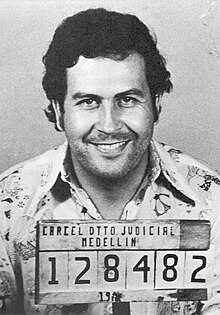

6°7′4″N 75°35′6″W / 6.11778°N 75.58500°W / 6.11778; -75.58500 La Catedral was a prison overlooking the city of Medellín, in Colombia. The prison was built to specifications ordered by Medellín Cartel leader Pablo Escobar, under a 1991 agreement with the Colombian government in which Escobar would surrender to authorities and serve a maximum term of five full years and the Colombian government would not extradite him to the United States. In addition to the facility being built to Escobar's specifications, Escobar was also given the right to choose who would guard him and it was believed he chose guards loyal only to him. Moreover, the prison was believed to have been designed more to keep out Escobar's enemies and protect him from assassination attempts, than to keep Escobar in.

The finished prison was often called "Hotel Escobar" or "Club Medellín", because of its amenities. La Catedral featured a football pitch, giant doll house, bar, jacuzzi and waterfall. Escobar also had a telescope installed that allowed him to look down onto the city of Medellín to his daughter's residence while talking on the phone with her.

PBS reports that although the government was willing to turn a blind eye to Escobar continuing his drug smuggling, the arrangement fell apart when it was reported Escobar had four of his lieutenants tortured and murdered within La Catedral. The Colombian government decided it had to move Escobar to a standard prison, an order Escobar refused. In July 1992, after serving one year and one month, Escobar again went on the run. With the Colombian National Army surrounding La Catedral's facility, it is said Escobar simply walked out the back gate. The ensuing manhunt employed a 600-man unit force, specially trained by the United States Delta Force, named Search Bloc and led by Colonel Hugo Martínez.

Location advantage

Fog comes over after six o'clock in the evening and returns foggy at dawn. Therefore, air assault is impossible to carry out. The location's steep topography also prevented the military or rival cartels from attacking La Catedral easily. In addition, Pablo Escobar also had a large magazine that ensured his safety in the prison.

Current day

La Catedral remained deserted for several years. In 2007, a group of Benedictine monks from the Benedictina Fraternidad Monastica Santa Gertrudis arrived at the site and transformed it. The monks came there because it is a great place for meditating and away from the city. They built a chapel, a library, a cafeteria, a guest-house for religious pilgrimages, workshops and a memorial to victims of the cartel in the prison. In addition, the monks hired laid-off people to help with the daily running of La Catedral. Considering their efforts of reconstructing the prison, the city Envigado then ceded the entire prison to those monks.

Pictures

File:Helipad at La Catedral, the former Pablo Escobar prison overlooking the City of Medellin.jpg

See also

References

- ^ "The Godfather of Cocaine". Frontline (#1309). PBS. March 25, 1997.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Campagna, Jeff (2014-06-07). "Pablo Escobar's Private Prison Is Now Run by Monks for Senior Citizens". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- Thompson, David P. (1996). "Pablo Escobar, Drug Baron: His surrender, imprisonment, and escape". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 19: 55–91. doi:10.1080/10576109608435996.