| Revision as of 01:51, 7 December 2020 view sourceNSH001 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers20,169 edits the early morning fix: consistent citation style; usual fixes; please note missing full cite for Harris & Ferry 2017; fix empty unknown parm error← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:17, 7 December 2020 view source Selfstudier (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers41,286 edits →Sharon, Olmert and Bush: Quote not neededNext edit → | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

| Avi Primor in 2002 described the implications of the plan: "Without anyone taking notice, a process is underway establishing a "Palestinian state" limited to the Palestinian cities, a "state" comprised of a number of separate, sovereign-less enclaves, with no resources for self-sustenance."{{sfn|Primor|2002}} Commenting on these plans in 2006, Elisha Efrat, Professor of urban geography at ] argued that any state created on these fragmented divisions would be neither economically viable nor amenable to administration.{{efn|'It is quite clear that a Palestinian State with so many territorial enclaves will not be able to manage economic functions and administration. Even if its sovereign territory were greater, and even if some of the enclaves were connected into a continued territorial unity, the main communications arteries that are under Israeli dominance running from north to south and from west to east, and those along the Judean Desert that are under Israeli dominance, might perpetuate their spatial fragmentation.' {{harv|Efrat|2006|p=199}}}} | Avi Primor in 2002 described the implications of the plan: "Without anyone taking notice, a process is underway establishing a "Palestinian state" limited to the Palestinian cities, a "state" comprised of a number of separate, sovereign-less enclaves, with no resources for self-sustenance."{{sfn|Primor|2002}} Commenting on these plans in 2006, Elisha Efrat, Professor of urban geography at ] argued that any state created on these fragmented divisions would be neither economically viable nor amenable to administration.{{efn|'It is quite clear that a Palestinian State with so many territorial enclaves will not be able to manage economic functions and administration. Even if its sovereign territory were greater, and even if some of the enclaves were connected into a continued territorial unity, the main communications arteries that are under Israeli dominance running from north to south and from west to east, and those along the Judean Desert that are under Israeli dominance, might perpetuate their spatial fragmentation.' {{harv|Efrat|2006|p=199}}}} | ||

| Sharon eventually ] in 2005, and in the ensuing years, during the ] interregnum and the government of ] it became a commonplace to speak of the result there, where ] assumed sole authority over the internal administration of the Strip, as the state of Hamastan.{{efn|'If Ariel Sharon were able to hear the news from the Gaza Strip and West Bank, he would call his loyal aide, ], and say with a big laugh: "We did it, Dubi." Sharon is in a coma, but his plan is alive and kicking. Everyone is now talking about the state of Hamastan. In his house, they called it a bantustan, after the South African protectorates designed to perpetuate apartheid.' {{harv|Eldar|2007}}}}{{efn|"Israeli politicians lost no time exploiting these fears increasingly employing the term ''Hamastan'' - a neologism for the concept of a Hamas-dominated Palestinian Islamist theocracy under Iranian tutelage - to describe these circumstances; "before our very eyes", as Netanyahu warned, "Hamastan has been established, the step-child of Iran and the Taliban"." {{harv|Ram|2009|p=82}}}} At the same time, according to ], the Sharon plan to apply the same policy of creating discontinuous enclaves for Palestinians in the West Bank was implemented.{{efn|'Alongside the severance of Gaza from the West Bank, a policy now called "isolation," the Sharon-Peres government and the Olmert-Peres government that succeeded it carried out the bantustan program in the West Bank. The Jordan Valley was separated from the rest of the West Bank; the south was severed from the north; and all three areas were severed from East Jerusalem. The "two states for two peoples" plan gave way to a "five states for two peoples" plan: one contiguous state, surrounded by settlement blocs, for Israel, and four isolated enclaves for the Palestinians.' {{harv|Eldar|2007}}}}The maps for Sharon's disengagement from Gaza, Camp David and Oslo are similar to each other and to the 1967 Allon plan.{{sfn|Makdisi|2012|p=92}} By 2005, together with the Separation Wall, that area had been potted with 605 closure barriers whose overall effect was to create a 'matrix of contained quadrants controllable from well-defended, fixed military positions and settlements.{{efn|"To make this grid possible, more than 2,710 homes and workplaces in the West Bank have been completely destroyed, and an additional 39,964 others have been damaged, since the beginning of the Intifada." {{harv|Haddad|2009|p=280}}}}{{efn|"At times, the politics of separation/partition has been dressed up as a formula for peaceful settlement at others as a bureaucratic-territorial arrangement of governance, and most recently as a means of unilaterally imposed domination, oppression and fragmentation of the Palestinian people and their land. The Oslo Accords of the 1990s left the Israeli military in control of the interstices of an archipelago of about two hundred separate zones of Palestinian restricted autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza." {{harv|Weizman|2012|pp=10–11}}}} Olmert's ] (or convergence plan) are terms used to describe a method whereby Israel creates a future Palestinian state of it's own design as foreseen by the Allon plan, to minimize the amount of land on which a Palestinian state would exist by fixing facts on the ground to affect future negotiations.{{sfn|Harris|Ferry|2017|p=211 |

Sharon eventually ] in 2005, and in the ensuing years, during the ] interregnum and the government of ] it became a commonplace to speak of the result there, where ] assumed sole authority over the internal administration of the Strip, as the state of Hamastan.{{efn|'If Ariel Sharon were able to hear the news from the Gaza Strip and West Bank, he would call his loyal aide, ], and say with a big laugh: "We did it, Dubi." Sharon is in a coma, but his plan is alive and kicking. Everyone is now talking about the state of Hamastan. In his house, they called it a bantustan, after the South African protectorates designed to perpetuate apartheid.' {{harv|Eldar|2007}}}}{{efn|"Israeli politicians lost no time exploiting these fears increasingly employing the term ''Hamastan'' - a neologism for the concept of a Hamas-dominated Palestinian Islamist theocracy under Iranian tutelage - to describe these circumstances; "before our very eyes", as Netanyahu warned, "Hamastan has been established, the step-child of Iran and the Taliban"." {{harv|Ram|2009|p=82}}}} At the same time, according to ], the Sharon plan to apply the same policy of creating discontinuous enclaves for Palestinians in the West Bank was implemented.{{efn|'Alongside the severance of Gaza from the West Bank, a policy now called "isolation," the Sharon-Peres government and the Olmert-Peres government that succeeded it carried out the bantustan program in the West Bank. The Jordan Valley was separated from the rest of the West Bank; the south was severed from the north; and all three areas were severed from East Jerusalem. The "two states for two peoples" plan gave way to a "five states for two peoples" plan: one contiguous state, surrounded by settlement blocs, for Israel, and four isolated enclaves for the Palestinians.' {{harv|Eldar|2007}}}}The maps for Sharon's disengagement from Gaza, Camp David and Oslo are similar to each other and to the 1967 Allon plan.{{sfn|Makdisi|2012|p=92}} By 2005, together with the Separation Wall, that area had been potted with 605 closure barriers whose overall effect was to create a 'matrix of contained quadrants controllable from well-defended, fixed military positions and settlements.{{efn|"To make this grid possible, more than 2,710 homes and workplaces in the West Bank have been completely destroyed, and an additional 39,964 others have been damaged, since the beginning of the Intifada." {{harv|Haddad|2009|p=280}}}}{{efn|"At times, the politics of separation/partition has been dressed up as a formula for peaceful settlement at others as a bureaucratic-territorial arrangement of governance, and most recently as a means of unilaterally imposed domination, oppression and fragmentation of the Palestinian people and their land. The Oslo Accords of the 1990s left the Israeli military in control of the interstices of an archipelago of about two hundred separate zones of Palestinian restricted autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza." {{harv|Weizman|2012|pp=10–11}}}} Olmert's ] (or convergence plan) are terms used to describe a method whereby Israel creates a future Palestinian state of it's own design as foreseen by the Allon plan, to minimize the amount of land on which a Palestinian state would exist by fixing facts on the ground to affect future negotiations.{{sfn|Harris|Ferry|2017|p=211}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| According to professor Saeed Rahnema, the Allon, Drobles and Sharon plans envisaged "the establishment of settlements on the hilltops surrounding Palestinian towns and villages and the creation of as many Palestinian enclaves as possible." while many aspects formed the basis of all the failed "peace plans" that ensued.{{sfn|Rahnema|2014}} The ], the ] ] plan, ]'s plan, ]'s "Allon Plus" plan, the ], and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw a territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel,{{efn|"Israel responded to the second intifada with a strategy of collective punishment aimed at a return to the logic of Oslo, whereby a weak Palestinian leadership would acquiesce to Israeli demands and a brutalized population would be compelled to accept a "state" made up of a series of Bantustans. Though the language may have changed slightly, the same structure that has characterized past plans remains. The Allon plan, the WZO plan, the Begin plan, Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, Barak's "generous offer," and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw Israeli control of significant West Bank territory, a Palestinian existence on minimal territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel, and a Palestinian or Arab entity that would assume responsibility for internal policing and civil matters." {{harv|Cook|Hanieh|2006|pp=346–347}}}}{{efn|The 1968 Allon Plan called for placing settlements in sparsely populated lands of the Jordan River Valley, thus ensuring Jewish demographic presence in the farthest location within biblical Israel. This was later complemented by the 1978 Drobles Plan, named after its author Matityahu Drobles, which called for a "belt of settlements in strategic locations … throughout the whole land of Israel … for security and by right." The logic of the Drobles Plan actually guided the wave of settlements that occurred in the 1990s, thus turning the settlements into an integral element of Israel's tactical control over and surveillance of Palestinians in the West Bank. | According to professor Saeed Rahnema, the Allon, Drobles and Sharon plans envisaged "the establishment of settlements on the hilltops surrounding Palestinian towns and villages and the creation of as many Palestinian enclaves as possible." while many aspects formed the basis of all the failed "peace plans" that ensued.{{sfn|Rahnema|2014}} The ], the ] ] plan, ]'s plan, ]'s "Allon Plus" plan, the ], and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw a territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel,{{efn|"Israel responded to the second intifada with a strategy of collective punishment aimed at a return to the logic of Oslo, whereby a weak Palestinian leadership would acquiesce to Israeli demands and a brutalized population would be compelled to accept a "state" made up of a series of Bantustans. Though the language may have changed slightly, the same structure that has characterized past plans remains. The Allon plan, the WZO plan, the Begin plan, Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, Barak's "generous offer," and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw Israeli control of significant West Bank territory, a Palestinian existence on minimal territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel, and a Palestinian or Arab entity that would assume responsibility for internal policing and civil matters." {{harv|Cook|Hanieh|2006|pp=346–347}}}}{{efn|The 1968 Allon Plan called for placing settlements in sparsely populated lands of the Jordan River Valley, thus ensuring Jewish demographic presence in the farthest location within biblical Israel. This was later complemented by the 1978 Drobles Plan, named after its author Matityahu Drobles, which called for a "belt of settlements in strategic locations … throughout the whole land of Israel … for security and by right." The logic of the Drobles Plan actually guided the wave of settlements that occurred in the 1990s, thus turning the settlements into an integral element of Israel's tactical control over and surveillance of Palestinians in the West Bank. | ||

Revision as of 11:17, 7 December 2020

| A request that this article title be changed to Areas of the West Bank under Palestinian rule is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (November 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Area A and B under the Oslo II Accord

Area A and B under the Oslo II Accord Proposal in the Trump peace plan

Proposal in the Trump peace plan

| Israeli-occupied territories | |

|---|---|

| Historical | |

| Ongoing | Occupied Palestinian territories 2024 invasion of Lebanon (ongoing) |

| Proposed | |

The West Bank bantustans, or West Bank cantons, figuratively described as the Palestine Archipelago, are the proposed enclaves for the Palestinians of the West Bank under a variety of US and Israeli-led proposals to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The process of creating the fragmented Palestinian zones has been described as "encystation" by Professor Glenn Bowman, Emeritus Professor of Politics and International Relations at Kent University, and as "enclavization" by Professor Ghazi Falah at the University of Akron. The term "bantustanization" was first used by Azmi Bishara in 1995, though Yassir Arafat had made the analogy earlier in peace talks to his interlocutors. "Researchers and writers from the Israeli left" began using it in the early 2000s, with Meron Benvenisti referring in 2004 to the territorial, political and economic fragmentation model being pursued by the Israeli government.

The terms have also been used to describe Areas A and B under the 1995 Oslo II Accord, and the similar but less formal situation between 1967 and 1995. The area of the West Bank under civil control of the Palestinian National Authority is composed of 165 "islands". Both the Oslo Accord maps and subsequent cantonized peace plans have been referred to as "Swiss cheese".

The creation of the bantustans has been called "the most outstanding geopolitical occurrence of the past quarter century."

History

1967-1995

After the 1967 Six-Day War, a small group of officers and senior Israeli officials advocated that Israel unilaterally plan for a Palestinian mini-state or "canton", in the north of the West Bank. Policymakers did not implement this cantonal plan at the time. Defense minister Moshe Dayan said that Israel should keep the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In early 1968, Yigal Allon, the Israeli minister after whom the 1967 Allon Plan is named, proposed reformulating his plan by transferring some Palestinian areas back to Jordan, for fear that the resulting Palestinian areas "would be identified as... some kind of South African bantustan".

According to former Israeli ambassador and vice president of Tel Aviv University Avi Primor, writing in 2002, in the top echelons of the Israeli security establishment in the 1970s and 1980s there was widespread empathy for South Africa's apartheid system, and were particularly interested in that country's resolution of the demographic issue by inventing bantustan "homelands" for various groups of the indigenous black population. Pro-Palestinian circles and scholars, despite the secrecy of the tacit alliance between Israel and South Africa, were familiar with ongoing arrangements between the two in military and nuclear matters, though the thriving cooperation between Israel and the Bantustans themselves was a subject that remained neglected until recently, when South Africa's archives began to be opened up. By the early 1970s, Arabic-language magazines began to compare the Israeli proposals for a Palestinian autonomy to the Bantustan strategy of South Africa.

In late 1984 some embarrassment was caused when the Israeli settlement of Ariel in the West Bank paired itself as a sister city with Bisho, the "capital" of the ostensibly independent Bantustan of Ciskei. Shortly afterwards, Shimon Peres the new Prime Minister of a Labour-Likud national coalition government, condemned apartheid as an "idiotic system".

Oslo Accords

Soon after the joint signing of the Oslo I Accord on 13 September 1993, Yassir Arafat and Simon Peres engaged in follow-up negotiations at the Unesco summit held in December that year in Granada. Arafat was incensed at what he saw as the impossible terms rigidly set by Peres regarding Israeli control of border exits with Jordan, stating that what he was being asked to sign off on resembled a bantustan.. This, Peres insisted, was what had been agreed to at Oslo. Subsequently, on 4 May 1994, Israel and the PLO signed the Gaza–Jericho Agreement that stipulated arrangements for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from both named areas. Azmi Bishara commented that the model envisaged for Gaza was a Bantustan, one even more restrictive in its implications and scope than the ones existing in South Africa. This in turn was taken to signal that the same model would be applied in the future to the West Bank, as with Jericho.

The 1995 Oslo II Accord formalized the fragmentation of the West Bank, allotting to the Palestinians over 60 disconnected islands; by the end of 1999 the West Bank had been divided into 227 separate entities, most of which were no more than 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi) (about half the size of New York's Central Park). These areas, comprising what is known as Area A (c.1005km2; 17.7% of the West Bank) and Area B (c.1035km2; 18.3% of the West Bank), formalized the legal limitation to urban expansion of Palestinian populated areas outside of these fragments. These arrangements were, however, agreed at Oslo to be temporary, with the West Bank to "be gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction" by 1997; no such transfers were made.

The Oslo map has been referred to as the Swiss Cheese map. The Palestinian negotiators at Oslo were not shown the Israeli map until 24 hours before the agreement was due to be signed, and had no access to maps of their own in order to confirm what they were being shown. Yasser Arafat was quoted by Uri Savir, the Israeli chief negotiator at Oslo, as follows: "Arafat glared at in silence, then sprang out of his chair and declared it to be an insufferable humiliation. "These are cantons! You want me to accept cantons! You want to destroy me!""

Professor Shari Motro, then an Israeli secretary in the Oslo delegation, described in 2005 part of the story behind the maps:

Some people claim that the Oslo process was deliberately designed to segregate Palestinians into isolated enclaves so that Israel could continue to occupy the West Bank without the burden of policing its people. If so, perhaps the map inadvertently revealed what the Israeli wordsmiths worked so diligently to hide. Or perhaps Israel's negotiators purposefully emphasized the discontinuity of Palestinian areas to appease opposition from the Israeli right, knowing full well that Arafat would fly into a rage. Neither is true. I know, because I had a hand in producing the official Oslo II map, and I had no idea what I was doing. Late one night during the negotiations, my commander took me from the hotel where the talks were taking place to an army base, where he led me to a room with large fluorescent light tables and piles of maps everywhere. He handed me some dried-out markers, unfurled a map I had never seen before, and directed me to trace certain lines and shapes. Just make them clearer, he said. No cartographer was present, no graphic designer weighed in on my choices, and, when I was through, no Gilad Sher reviewed my work. No one knew it mattered.

Motro's then superior officer, Shaul Arieli, who drew and was ultimately responsible for the Oslo maps, explained that the Palestinian enclaves were created by a process of subtraction, consigning the Palestinians to those areas that the Israelis considered "unimportant":

The process was very easy. In the agreement signed in '93, all those areas that would be part of final status agreement—settlements, Jerusalem, etc.—were known. So I took out those areas, along with those roads and infrastructure that were important to Israel in the interim period. It was a new experience for me. I did not have experience of mapmaking before. I of course used many different civilian and military organizations to gather data on the infrastructure, roads, water pipes, etc. I took out what I thought important for Israel.

The islands isolate Palestinian communities from one another, whilst allowing them to be "well guarded" and easily contained by the Israeli military. The arrangements result in "inward growth" of Palestinian localities, rather than urban sprawl. Many observers, including Edward Said, Norman Finkelstein and seasoned Israeli analysts such as Meron Benvenisti were highly critical of the arrangements, with Benvenisti concluding that the Palestinian self-rule sketched out in the agreements was little more than a euphemism for Bantustanization. Defenders of the agreements made in the 1990s between Israel and the PLO rebuffed criticisms that the effect produced was similar to that of South Africa's apartheid regime, by noting that, whereas the Bantustan structure was never endorsed internationally, the Oslo peace process's memoranda had been underwritten and supported by an international concert of nations, both in Europe, the Middle East and by the Russian Federation.

Wye River Accord

A subsequent Wye River Accord negotiated with Binjamin Netanyahu drew similar criticism. Noam Chomsky argued that the situation envisaged still differed from the historical South African model in that Israel did not subsidize the fragmented territories it controlled, as South Africa did, leaving that to international aid donors; and secondly, despite exhortations from the business community, it had, at that period, failed to set up maquiladoras or industrial parks to exploit cheap Palestinian labour, as had South Africa with the bantustans. He did draw an analogy however between the two situations by claiming that the peace negotiations had led to a corrupt elite, the Palestinian Authority, playing a role similar to that of the black leadership appointed by South Africa to administer their Bantustans. Chomsky concluded that it was in Israel's interest to agree to call these areas states.

Camp David Summit 2000

Talks to achieve a comprehensive resolution of the conflict were renewed at the Camp David Summit in 2000, only to break down. Accounts differ as to which side bore responsibility for the failure. Ehud Barak's offer was widely reported as 'generous' and, according to Dennis Ross, a participant, would have conceded Palestinians 97% of the West Bank. Others contend that despite an undertaking to withdraw from most of their territory, the resulting entity would still have consisted of several bantustans. Israeli journalist Ze'ev Schiff argued that "the prospect of being able to establish a viable state was fading right before eyes. They were confronted with an intolerable set of options: to agree to the spreading occupation... or to set up wretched Bantustans, or to launch an uprising."

Sharon, Olmert and Bush

On his election to the Israeli Prime Ministership in March 2001, Ariel Sharon expressed his determination not to allow the Road map for peace advanced by the first administration of George W. Bush to hinder his territorial goals, and stated that Israeli concessions at all prior negotiations were no longer valid. Several prominent Israeli analysts concluded that his plans torpedoed the diplomatic process, with some claiming that his vision of Palestinian enclaves resembled the Bantustan model,

It emerged that in private Sharon indeed had openly confided, even to foreign statesmen, that the Apartheid Bantustan example furnished an appropriate model for what he had in mind. By 2003 he was forthcoming in avowing that it informed his plan to construct a "map of a (future) Palestinian state". Not only was the Gaza Strip to be reduced to a bantustan, but the model there, according to Meron Benvenisti, was to be transposed to the West Bank by ensuring, simultaneously, that the Wall itself broke up into three fragmented entities Jenin-Nablus, Bethlehem-Hebron and Ramallah.

Avi Primor in 2002 described the implications of the plan: "Without anyone taking notice, a process is underway establishing a "Palestinian state" limited to the Palestinian cities, a "state" comprised of a number of separate, sovereign-less enclaves, with no resources for self-sustenance." Commenting on these plans in 2006, Elisha Efrat, Professor of urban geography at TAU argued that any state created on these fragmented divisions would be neither economically viable nor amenable to administration.

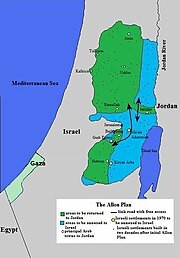

Sharon eventually disengaged from the Gaza in 2005, and in the ensuing years, during the Sharon-Peres interregnum and the government of Ehud Olmert it became a commonplace to speak of the result there, where Hamas assumed sole authority over the internal administration of the Strip, as the state of Hamastan. At the same time, according to Akiva Eldar, the Sharon plan to apply the same policy of creating discontinuous enclaves for Palestinians in the West Bank was implemented.The maps for Sharon's disengagement from Gaza, Camp David and Oslo are similar to each other and to the 1967 Allon plan. By 2005, together with the Separation Wall, that area had been potted with 605 closure barriers whose overall effect was to create a 'matrix of contained quadrants controllable from well-defended, fixed military positions and settlements. Olmert's Realignment plan (or convergence plan) are terms used to describe a method whereby Israel creates a future Palestinian state of it's own design as foreseen by the Allon plan, to minimize the amount of land on which a Palestinian state would exist by fixing facts on the ground to affect future negotiations.

According to professor Saeed Rahnema, the Allon, Drobles and Sharon plans envisaged "the establishment of settlements on the hilltops surrounding Palestinian towns and villages and the creation of as many Palestinian enclaves as possible." while many aspects formed the basis of all the failed "peace plans" that ensued. The Allon Plan, the Drobles World Zionist Organization plan, Menachem Begin's plan, Benjamin Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, the 2000 Camp David Summit, and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw a territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel, as with the more recent Trump peace plan.

Netanyahu and Obama

In 2016, the last year of his presidency, Barack Obama and John Kerry discussed a number of detailed maps showing the fragmentation of the Palestinian areas. Advisor Ben Rhodes said that "the President was shocked to see how "systematic" the Israelis had been at cutting off Palestinian population centers from one another." These findings were discussed with the Israeli government; the Israelis "never challenged those findings". Obama's realization was reported to be the reason that he abstained on the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334 which condemned the settlements.

According to Haaretz's Chemi Shalev, in a speech marking the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, "Netanyahu thus envisages not only that Palestinians in the West Bank will need Israeli permission to enter and exit their "homeland", which was also the case for the Bantustans, but that the IDF will be allowed to continue setting up roadblocks, arresting suspects and invading Palestinian homes, all in the name of "security needs"."

Land confiscation

Main articles: Land expropriation in the West Bank, Declarations of State Land in the West Bank, Israeli demolition of Palestinian property, and Israeli West Bank barrierIn 2003, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Jean Ziegler reported that he:

is also particularly concerned by the pattern of land confiscation, which many Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals and non-governmental organizations have suggested is inspired by an underlying strategy of "Bantustanization". The building of the security fence/apartheid wall is seen by many as a concrete manifestation of this Bantustanization as, by cutting the OPT into five barely contiguous territorial units deprived of international borders, it threatens the potential of any future viable Palestinian State with a functioning economy to be able to realize the right to food of its own people.

The Financial Times published a 2007 U.N. map and explained "The UN mapmakers focused on land set aside for Jewish settlements, roads reserved for settler access, the West Bank separation barrier, closed military areas and nature reserves," and "What remains is an area of habitation remarkably close to territory set aside for the Palestinian population in Israeli security proposals dating back to postwar 1967."

In a 2013 report on the Palestinian economy in East Jerusalem, UNCTAD's conclusions noted increased demolitions of Palestinian property and homes as well as settlement growth in the areas surrounding East Jerusalem and Bethlehem adding "to the existing physical fragmentation between different Palestinian "bantustans" – drawing on South African experience of economically dependent, self-governed "homelands" existing within the orbit of the advanced metropolis,.." A 2015 report of the Norwegian Refugee Council noted the impact of Israeli policies in key areas of East Jerusalem, principally the Wall and settlement activity, particularly in regard to Givat HaMatos and Har Homa.

Trump peace plan

See also: Proposed Israeli annexation of the West Bank

The 2020 Trump peace plan proposed splitting a possible "State of Palestine" into five zones:

- A reduced Gaza Strip connected by a road to two uninhabited districts in the Negev desert;

- Part of the southern West Bank;

- A central area around Ramallah, almost trisected by a number of Israeli settlements;

- A northern area including Nablus, Jenin, and Tulkarm;

- A small zone including Qalqilya, surrounded by Israeli settlements.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas commented on the fragmented nature of the proposal at the United Nations Security Council, waving a picture of the fragmented cantons and stating: "This is the state that they will give us. It's like a Swiss cheese, really. Who among you will accept a similar state and similar conditions?" According to Professor Ian Lustick, the appellation "State of Palestine" applied to this archipelago of Palestinian-inhabited districts is not to be taken any more seriously than the international community took apartheid South Africa's description of the bantustans of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei as "independent nation-states."

When the plan emerged, Yehuda Shaul argued that the proposals were remarkably similar to the details set forth both in the 1979 Drobles Plan, written for the World Zionist Organization and entitled Master Plan for the Development of Settlements in Judea and Samaria, 1979–1983, and key elements of the earlier Allon Plan, aimed at ensuring Jewish settlement in the Palestinian territories, while blocking the possibility that a Palestinian state could ever emerge.

The plan in principle contemplates a future Palestinian state, "shrivelled to a constellation of disconnected enclaves, following Israeli annexation," while a group of UN human rights experts said "What would be left of the West Bank would be a Palestinian Bantustan, islands of disconnected land completely surrounded by Israel and with no territorial connection to the outside world." Commenting on the plan, Daniel Levy, former Israeli negotiator and president of the U.S./Middle East Project wrote that "The visuals of the map proposed are a dead giveaway: a patchwork of Palestinian islands best viewed alongside the map of South Africa's apartheid-era Bantustans." The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory Michael Lynk commented that Trump's proposal was not a recipe for peace as much as an endorsement of "the creation of a 21st century Bantustan in the Middle East."

Contiguity

Rather than territorial contiguity, Sharon had in mind transportation contiguity. In 2004 Israel asked international donors to fund a new road network for Palestinians, that would run under and over the existing settler-only network. Since acceptance would have implied official approval of the settlement enterprise, the World Bank refused. While Israelis could traverse the contiguous Area C, settler-only roads divided the West Bank into a series of non-contiguous areas for Palestinians wanting to reach Areas A and B.

In 2004, Colin Powell was asked what George W. Bush meant when he spoke of a "contiguous Palestine"; Powell explained that " was making the point that you can't have a bunch of little Bantustans or the whole West Bank chopped up into noncoherent, noncontiguous pieces, and say this is an acceptable state." In 2008, the last year of his presidency, Bush stated "Swiss cheese isn't going to work when it comes to the outline of a state. To be viable, a future Palestinian state must have contiguous territory."

In 2020, former US Ambassador to Israel, Martin Indyk, noted that the Trump Plan proposed transportational contiguity instead of territorial contiguity, via "tunnels that would connect the islands of Palestinian sovereignty. Those tunnels, of course, would be under Israeli control."

Names

Main article: Media coverage of the Arab–Israeli conflictA variety of terms are used to describe these areas of the West Bank, including "enclaves," "cantons," "bantustans," and "open-air prisons".

The name "cantons" is considered to imply a neutral concept where political implications are left to be determined, whereas the name "bantustans" is considered to have economic and political implications and to imply the lack of meanginful sovereignty. The name "islands" or "archipelago" is considered to communicate how the infrastructure of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank has disrupted contiguity between Palestinian areas.

Notes

- Also contracted as "Palutustans".'The experience of the past four decades puts a question mark over this assumption. If a Palestinian state is not established, Israel will most likely continue to administer the area, possibly allotting crumbs of sovereignty to Palestinian groups in areas that will continue to function as "Palutustans" (Palestinian Bantustans)." Conversely Francis Boyle, former Amnesty International USA board member and legal advisor to the Palestinians in Madrid (1991-1993), and presently professor of International Law at the University of Illinois College of Law, after describing the process of peace negotiations as designed to create a Bantustan for Palestinians, argued that historically, it was Western imperial colonial powers, whose policies in his view had been racist and genocidal that, in creating Israel, had effectively established what was a Bantustan for the Jewish people themselves, an entity he called "Jewistan".

- "In 2009, French artist Julien Bousac designed a map of the West Bank titled "L'archipel de Palestine orientale, " or "The Archipelago of Eastern Palestine"... Bousac's map illustrates — via a military and a tourist imaginary — how the US-brokered Oslo Accords fragmented the West Bank into enclaves separated by checkpoints and settlements that maintain Israeli control over the West Bank and circumscribe the majority of the Palestinian population to shrinking Palestinian city and village centers." (Kelly 2016, pp. 723–745)

- "Faced with widely drawn international parallels between the West Bank and the Bantustans of apartheid South Africa, senior figures in Mr Netanyahu's Likud party have begun to admit the danger.' (Stephens 2013)

- "In the West Bank Israel has managed to turn the governorates there into Bantustans only connected through an Israeli controlled (Area C) territory." (ITAN 2015, p. 889)

- "90 percent of the population of the West Bank was divided into 165 islands of ostensible PA control." (Thrall 2017, p. 144)

- "The reality of the Palestinian Bantustans, reservations or enclaves — is a fact on the ground. Their creation is the most outstanding geopolitical occurrence of the past quarter century."

- 'During the early days of the occupation a handful of senior Israeli officials and army officers advocated unilateral plans for a Palestinian satellite mini-state, autonomous region, or "canton" — Bantustan actually — in the northern half of the West Bank, but the policymakers would have none of this.' (Raz 2020, p. 278)

- "Many in the top echelons of the security establishment in the 1970s and 1980s had a warm spot in their hearts for the white apartheid regime in South Africa that was derived not only from utilitarian interests, but also from sympathy for the white minority rulers in that country. One of the elements of the old South African regime that stirred much interest in Israel remains current to this day: To seemingly solve the demographic problem that troubled the white South Africans (that is, to hang on to all of South Africa without granting equal rights, civil rights and the vote to blacks), the South African regime created a fiction known by the name Bantustans, later changed to Homelands." (Primor 2002)

- "It will be the end of me. I can't go for a Bantustan. Don't push me into a corner, my back's already against the wall. How will I tell my people that you control every entry, from every direction? I'm not in power because of a popular majority, but thanks to the personal credit I've accumulated. For me, this is a disaster, a catastrophe." (Gil 2020, p. 163)

- "In any case, what was on offer at Oslo was a territorially discontinuous Palestinian Bantustan (divided into over sixty disconnected fragments) that would have had no control over water resources, borders, or airspace, much less an independent economy, currency, or financial system, and whose sovereignty, nominal as it was, would be punctuated by heavily fortified Israeli colonies and an autonomous Jewish road network, all of which would be effectively under Israeli army control. Even this, however, was never realized." (Makdisi 2005, pp. 443–461)

- "By December 1999, the Gaza Strip had been divided into three cantons and the West Bank into 227, the majority of which were no larger than two square kilometers in size. Both areas were effectively severed from East Jerusalem. While Palestinians maintained control over many of the cantons and were promised authority over more if not most, Israel maintained jurisdiction over the land areas in between the cantons, which in effect gave Israel control over all the land and its disposition. Hence, the actual amount of land under Palestinian authority proved far less important than the way that land was arranged and controlled." (Roy 2004, pp. 365–403)

- 'When I was in Israel recently, giving talks on the thirtieth anniversary of the occupation, I quoted a passage about the Bantustans from a standard academic history of South Africa. You didn't have to comment. Everybody who had their eyes open could recognize it. There were many people who just refuse to see what's happening, including most of the doves. But if you pay attention to what's happening, that's the description. So it is absurd for Israel to be to the racist side of South Africa under Apartheid. I assume that sooner or later they will agree to call these things states.' (Chomsky & Barsamian 2001, p. 90)

- 'In April he said that Israel would not withdraw from most of the West Bank, would continue to occupy the Jordan River Valley and the roads leading to them, would make no concessions on Jerusalem, would "absolutely not" evacuate a single settlement "at any price" and would not cede control of the West Bank water aquifers. In case that was not sufficiently clear, over the next year he repeatedly said that the Israeli concessions at Oslo, Camp David, and Taba were no longer valid. A number of prominent Israeli analysts commented that Sharon's intentions were to torpedo the diplomatic process, continue the Israeli occupation, and limit the Palestinians to a series of enclaves surrounded by the Israeli settlements; some even wrote that Sharon's long term strategy resembled that of the "Bantustans" created by the South African apartheid regime' (Slater 2020, p. 303).

- 'Just as in the Palestinian territories, blacks and colored people in South Africa were given limited autonomy in the country's least fertile areas. Those who remained outside these isolated enclaves, which were disconnected from each other, received the status of foreign workers, without civil rights. A few years ago, Italian Foreign Minister Massimo D'Alema told Israeli friends that shortly before he was elected prime minister, Sharon told him that the bantustan plan was the most suitable solution to our conflict.'; 'Sharon's conception of a Palestinian 'state' is in fact very akin to the sub-sovereign Bantustan model of apartheid South Africa, a comparison which he is reported to make in private.'

- 'In 2003, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon revealed that he relied on South Africa's Bantustan model in constructing a possible "map of a Palestinian state"." (Feld 2014, p. 99,138)

- "with breathtaking daring, Sharon submits a plan that appears to promise the existence of a "Jewish democratic state" via "separation", "the end of the conquest", the "dismantling of settlements" – and also the imprisonment of some 3 million Palestinians in bantustans. This is an "interim plan" that is meant to last forever. The plan will last, however, only as long as the illusion is sustained that "separation" is a means to end the conflict.' (Benvenisti 2004)

- 'It is quite clear that a Palestinian State with so many territorial enclaves will not be able to manage economic functions and administration. Even if its sovereign territory were greater, and even if some of the enclaves were connected into a continued territorial unity, the main communications arteries that are under Israeli dominance running from north to south and from west to east, and those along the Judean Desert that are under Israeli dominance, might perpetuate their spatial fragmentation.' (Efrat 2006, p. 199)

- 'If Ariel Sharon were able to hear the news from the Gaza Strip and West Bank, he would call his loyal aide, Dov Weissglas, and say with a big laugh: "We did it, Dubi." Sharon is in a coma, but his plan is alive and kicking. Everyone is now talking about the state of Hamastan. In his house, they called it a bantustan, after the South African protectorates designed to perpetuate apartheid.' (Eldar 2007)

- "Israeli politicians lost no time exploiting these fears increasingly employing the term Hamastan - a neologism for the concept of a Hamas-dominated Palestinian Islamist theocracy under Iranian tutelage - to describe these circumstances; "before our very eyes", as Netanyahu warned, "Hamastan has been established, the step-child of Iran and the Taliban"." (Ram 2009, p. 82)

- 'Alongside the severance of Gaza from the West Bank, a policy now called "isolation," the Sharon-Peres government and the Olmert-Peres government that succeeded it carried out the bantustan program in the West Bank. The Jordan Valley was separated from the rest of the West Bank; the south was severed from the north; and all three areas were severed from East Jerusalem. The "two states for two peoples" plan gave way to a "five states for two peoples" plan: one contiguous state, surrounded by settlement blocs, for Israel, and four isolated enclaves for the Palestinians.' (Eldar 2007)

- "To make this grid possible, more than 2,710 homes and workplaces in the West Bank have been completely destroyed, and an additional 39,964 others have been damaged, since the beginning of the Intifada." (Haddad 2009, p. 280)

- "At times, the politics of separation/partition has been dressed up as a formula for peaceful settlement at others as a bureaucratic-territorial arrangement of governance, and most recently as a means of unilaterally imposed domination, oppression and fragmentation of the Palestinian people and their land. The Oslo Accords of the 1990s left the Israeli military in control of the interstices of an archipelago of about two hundred separate zones of Palestinian restricted autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza." (Weizman 2012, pp. 10–11)

- "Israel responded to the second intifada with a strategy of collective punishment aimed at a return to the logic of Oslo, whereby a weak Palestinian leadership would acquiesce to Israeli demands and a brutalized population would be compelled to accept a "state" made up of a series of Bantustans. Though the language may have changed slightly, the same structure that has characterized past plans remains. The Allon plan, the WZO plan, the Begin plan, Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, Barak's "generous offer," and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw Israeli control of significant West Bank territory, a Palestinian existence on minimal territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel, and a Palestinian or Arab entity that would assume responsibility for internal policing and civil matters." (Cook & Hanieh 2006, pp. 346–347)

- The 1968 Allon Plan called for placing settlements in sparsely populated lands of the Jordan River Valley, thus ensuring Jewish demographic presence in the farthest location within biblical Israel. This was later complemented by the 1978 Drobles Plan, named after its author Matityahu Drobles, which called for a "belt of settlements in strategic locations … throughout the whole land of Israel … for security and by right." The logic of the Drobles Plan actually guided the wave of settlements that occurred in the 1990s, thus turning the settlements into an integral element of Israel's tactical control over and surveillance of Palestinians in the West Bank. The Allon and Drobles Plans and other similar colonization campaigns have invariably been motivated by five broad, interrelated reasons driving the settlement enterprise. They include control over economic resources, use of territory as a strategic asset, ensuring demographic presence and geographic control, reasserting control over the Jew's biblically promised homeland, and having exclusive rights to the territory (Kamrava 2016, pp. 79–80).

- "In sum, Israel continues to establish facts on the ground in these sensitive areas, thus undermining a future political settlement in East Jerusalem. Its policies reflect an ongoing effort to clear disputed areas in order to establish or expand settlements; change the demographic composition of East Jerusalem and strengthen Jewish presence, impede the development and expansion of Palestinian neighbourhoods, and prevent the prospects of creating a viable Palestinian capital with territorial contiguity." (NRC 2015, p. 26)

- The International Fact-Finding Mission on Israeli Settlements noted that "Various sources refer to settlement master plans, including the Allon Plan(1967), the Drobles Plan(1978)–later expanded as the Sharon Plan(1981)– and the Hundred Thousand Plan(1983). Although these plans were never officially approved, they have largely been acted upon by successive Governments of Israel. The mission notes a pattern whereby plans developed for the settlements have been mirrored in Government policy instruments and implemented on the ground." (UNHCR 2013, pp. 6–7)

- "This is not a recipe for a just and durable peace but rather endorses the creation of a 21st century Bantustan in the Middle East. The Palestinian statelet envisioned by the American plan would be scattered archipelagos of non-contiguous territory completely surrounded by Israel, with no external borders, no control over its airspace, no right to a military to defend its security, no geographic basis for a viable economy, no freedom of movement and with no ability to complain to international judicial forums against Israel or the United States." (Lynk 2020)

- "The Trump plan would thereby surround the Palestinian state with Israeli territory, severing its contiguity with Jordan and turning Jericho into a Palestinian enclave and the Palestinian state into a Bantustan... The result would be a Swiss cheese Palestinian state with no possibility of territorial contiguity. Instead, the Trump plan proposes 'transportational' contiguity, through tunnels that would connect the islands of Palestinian sovereignty. Those tunnels, of course, would be under Israeli control." (Indyk 2020)

- "The terms "enclaves," "cantons," "Bantustans," and "open-air prisons" are used by Palestinians and outside observers to describe these spaces." (Peteet 2016, p. 268)

- Ariel Sharon, Israel's Prime Minister since 2001, had long contended that the Bantustan model, so central to the apartheid system, is the most appropriate to the present Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Others, by contrast, have maintained that the Palestinian territories have been transformed into cantons whose final status is still to be determined. The difference in terminology between cantons and Bantustans is not arbitrary though. The former suggests a neutral territorial concept whose political implications and contours are left to be determined. The latter indicates a structural development with economic and political implications that put in jeopardy the prospects for any meaningfully sovereign viable Palestinian state. It makes the prospects for a binational state seem inevitable, if most threatening to the notion of ethnic nationalism.' (Farsakh 2005, p. 231)

Citations

- Yiftachel 2016, p. 320.

- Boyle 2011, pp. 13–17, p.60.

- Barak 2005, pp. 719–736.

- Baylouny 2009, pp. 39–68.

- Peteet 2016, pp. 247–281.

- Chaichian 2013, pp. 271–319.

- Bowman 2007, pp. 127–135.

- Falah 2005, pp. 1341–1372.

- Taraki 2008, pp. 6–20.

- Gil 2020, p. 162.

- Korn 2013, p. 122.

- Alissa 2013, p. 128.

- Harris 1984, pp. 169–189.

- ^ Motro 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Mohammed & Holland 2020.

- Hass 2018.

- Gorenberg 2006, p. 153.

- Lissoni 2015, pp. 53–55.

- Clarno 2009, pp. 66–67.

- Hunter 1986, p. 58.

- Parsons 2005, p. 93.

- Moghayer, Daget & Wang 2017, p. 4.

- Niksic, Eddin & Cali 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 39.

- Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 41.

- Motro 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Kamrava 2016, p. 95.

- Finkelstein 2003, p. 177.

- McMahon 2010, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Sabel 2011, p. 25.

- Chomsky & Barsamian 2001, p. 92.

- Goldschmidt 2018, p. 375.

- Slater 2001, pp. 171–199.

- Eldar 2007.

- Le More 2005, p. 990.

- Farsakh 2005, p. 231.

- Machover 2012, p. 55.

- Primor 2002.

- Makdisi 2012, p. 92.

- Harris & Ferry 2017, p. 211. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrisFerry2017 (help)

- Abu-Lughod 1981, p. 61(V).

- Rahnema 2014.

- ^ Srivastava 2020.

- ^ UNHRC 2020.

- Entous 2018.

- Shalev 2017.

- Ziegler 2003, p. 3.

- Makdisi 2012, pp. 92–93.

- UNCTAD 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Lustick 2005, p. 23.

- Shaul 2020.

- Levy 2020.

- Le More 2008, p. 170.

- Le More 2008, p. 132.

- Hass 2004.

- Blecher 2005.

- Peteet 2017, p. 93.

- Haaretz 2004.

- Evening Standard 2008.

- Kelly 2016, pp. 723–745.

Sources

- Abu-Lughod, Janet (4 September 1981). "The Fourth United Nations seminar on the Question of Palestine". United Nations. p. 61.

- Alissa, Sufyan (2013). "6: The economics of an independent Palestine". In Hilal, Jamil (ed.). Where Now for Palestine?: The Demise of the Two-State Solution. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-801-8.

- Barak, Oren (November 2005). "The Failure of the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process, 1993-2000". Journal of Peace Research. 42 (6): 719–736. doi:10.1177/0022343305057889. JSTOR 30042415. S2CID 53652363.

- Baylouny, Anne Marie (September 2009). "Fragmented Space and Violence in Palestine". International Journal on World Peace. 26 (3): 39–68. JSTOR 20752894.

- Benvenisti, Meron (26 April 2004). "Bantustan Plan for an apartheid Israel". The Guardian.

- Blecher, Robert (2005). "Transportational Contiguity". Middle East Report, also at Google books.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|postscript= - Bowman, Glenn (2007). "Israel's wall and the logic of encystation: Sovereign exception or wild sovereignty?". Focaal-European Journal of Anthropology (50): 127–136.

- Boyle, Francis (2011). The Palestinian Right of Return Under International Law. Clarity Press. ISBN 978-0-932-86393-5.

- Burns, Jacob; Perugini, Nicola (2016). "Untangling the Oslo Lines". In Manna, Jumana; Storihle, Sille (eds.). The Goodness Regime (PDF). pp. 38–43.

- Chaichian, Mohammed (2013). "Bantustans, Maquiladoras, and the Separation Barrier Israeli Style". Empires and Walls: Globalization, Migration, and Colonial Domination. BRILL. pp. 271–319. ISBN 978-9-004-26066-5.

- Chomsky, Noam; Barsamian, David (2001). Propaganda and the Public Mind: Conversations with Noam Chomsky. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-745-31788-5.

- Clarno, Andrew James (2009). The Empire's New Walls: Sovereignty, Neo-liberalism, and the Production of Space in Post-apartheid South Africa and Post-Oslo Palestine/Israel (Thesis). pp. 66–67. hdl:2027.42/127105. ISBN 978-1-244-00753-6.

- Cook, Catherine; Hanieh, Adam (2006). "35: Walling in People Walling out Sovereignty". In Beinin, Joel; Stein, Rebecca L. (eds.). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993-2005. Stanford University Press. pp. 338–347. ISBN 978-0-8047-5365-4.

- Displacement and the 'Jerusalem Question': An Overview of the Negotiations over East Jerusalem and Developments on the Ground (PDF) (Report). Norwegian Refugee Council. April 2015.

- Efrat, Elisha (2006). The West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17217-7.

- Eldar, Akiva (18 June 2007). "Sharon's Dream". Haaretz.

- Entous, Adam (9 July 2018). "The Maps of Israeli Settlements That Shocked Barack Obama". New Yorker Magazine.

- Falah, Ghazi-Walid (2005). "The Geopolitics of 'Enclavisation' and the Demise of a Two-State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict". Third World Quarterly. 26 (8): 1341–1372. doi:10.1080/01436590500255007. JSTOR 4017718. S2CID 154697979.

- Farsakh, Leila (Spring 2005). "Independence, Cantons, or Bantustans: Whither the Palestinian State?". Middle East Journal. 59 (2): 230–245. doi:10.3751/59.2.13. JSTOR 4330126.

- Feld, Marjorie N. (2014). Nations Divided: American Jews and the Struggle over Apartheid. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02972-0.

- Finkelstein, Norman G. (2003). Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (2nd ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-859-84442-7.

- Forced Population Transfer: the Case of Palestine, Segregation, Fragmentation and Isolation (PDF) (Report). BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights. February 2020.

- "George Bush pledges for Middle East peace within a year". Evening Standard. 11 January 2008.

- Gil, Avi (2020). Shimon Peres: An Insider's Account of the Man and the Struggle for a New Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-755-61703-6.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur, Jr (2018). A Concise History of the Middle East. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-97515-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gorenberg, Gershom (2006). The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-466-80054-0.

- Haddad, Toufic (2009). "Gaza: Birthing a Bantustan". In Tikva, Honig-Parnass; Haddad, Toufic (eds.). Between the Lines: Israel, the Palestinians, and the U.S. War on Terror. Haymarket Books. pp. 280–290 2. ISBN 978-1-608-46047-2.

- Harms, Gregory; Ferry, Todd M. (2017). The Palestine-Israel Conflict: A Basic Introduction 4th Ed. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2378-7.

- Harris, Brice, Jr (Summer 1984). "The South Africanization of Israel". Arab Studies Quarterly. 6 (3): 169–189. JSTOR 41857718.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hass, Amira (29 November 2004). "Donor Countries Won't Fund Israeli-planned Separate Roads for Palestinians". Haaretz.

- Hass, Amira (15 September 2018). "With Oslo, Israel's Intention Was Never Peace or Palestinian Statehood". Haaretz.

- Hunter, Jane (Spring 1986). "Israel and the Bantustans". Journal of Palestine Studies. 15 (3): 53–89. doi:10.2307/2536750. JSTOR 2536750.

- Indyk, Martin (February 2020). "Trump's Unfair Middle East Plan Leaves Nothing to Negotiate". Foreign Affairs.

- "Israeli annexation of parts of the Palestinian West Bank would break international law – UN experts call on the international community to ensure accountability". UNHRC. 16 June 2020.

- ITAN: Integrated Territorial Analysis of the Neighbourhoods. Scientific Report – Annexes; Applied Research 2013/1/22 Final Report (PDF) (Report). 11 March 2015. p. 889.

- Kamrava, Mehran (26 April 2016). The Impossibility of Palestine: History, Geography, and the Road Ahead. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22085-8.

- Kelly, Jennifer Lynn (September 2016). "Asymmetrical Itineraries: Militarism, Tourism, and Solidarity in Occupied Palestine" (PDF). American Quarterly. 68 (3): 723–745. doi:10.1353/aq.2016.0060. S2CID 151482682.

- Korn, Alina (2013). "6: The Ghettoization of the Palestinians". In Lentin, Ronit (ed.). Thinking Palestine. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-789-9.

- Le More, Anne (October 2005). "Killing with Kindness: Funding the Demise of a Palestinian State". International Affairs. 81 (5): 981–999. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00498.x. JSTOR 3569071.

- Le More, Anne (31 March 2008). International Assistance to the Palestinians after Oslo: Political guilt, wasted money. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-05232-5.

- Levy, Daniel (30 January 2020). "Don't Call It a Peace Plan". The American Prospect.

- Liel, Alon (2020). "Trump's "Deal of the Century" Is Modeled on South African Apartheid". Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture. 25 (1&2): 100–120.

- Lissoni, Arianna (2015). "Apartheid's Little Israel: Bophuthatswana". In Jacobs, Sean; Soske, Jon (eds.). Apartheid Israel: The Politics of an Analogy. Haymarket Books. pp. 53–66. ISBN 978-1-608-46519-4.

- Lustick, Ian (2005). "The One-State Reality: Reading the Trump-Kushner Plan as a Morbid Symptom". The Arab World Geographer. 23 (1): 23.

- Lynk, Michael (31 January 2020). "UN expert alarmed by 'lopsided' Trump plan, says will entrench occupation". UNHCR.

- Machover, Moshé (2012). Israelis and Palestinians: Conflict and Resolution. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-608-46148-6.

- Makdisi, Saree (2005). "Said, Palestine, and the Humanism of Liberation". Critical Inquiry. 31 (2): 443–461. doi:10.1086/430974. JSTOR 430974. S2CID 154951084.

- Makdisi, Saree (2012). Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06996-9.

- McMahon, Sean F. (2010). The Discourse of Palestinian-Israeli Relations: Persistent Analytics and Practices. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-20204-0.

- Moghayer, Taher J.T.; Daget, Yidnekachew Tesmamma; Wang, Xingping (2017). "Challenges of urban planning in Palestine". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 81: 1–5. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/81/1/012152.

- Mohammed, Arshad; Holland, Steve (11 February 2020). "Palestinians' Abbas, at U.N., says U.S. offers Palestinians 'Swiss cheese' state". Reuters.

- Motro, Shari (2005). "Lessons From the Swiss Cheese Map". Legal Affairs: 46–50.

- Niksic, Orhan; Eddin, Nur Nasser; Cali, Massimiliano (10 July 2014). Area C and the Future of the Palestinian Economy. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-1-464-80196-9.

- The Palestinian economy in East Jerusalem: Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration (PDF) (Report). UNCTAD. 2013.

- Parsons, Nigel (2005). The Politics of the Palestinian Authority: From Oslo to Al-Aqsa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94523-7.

- Peteet, Julie (Winter 2016). "The Work of Comparison: Israel/Palestine and Apartheid". Anthropological Quarterly. 89 (1): 247–281. doi:10.1353/anq.2016.0015. JSTOR 43955521. S2CID 147128703.

- Peteet, Julie (2017). Space and Mobility in Palestine. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02511-1.

- "Powell Warns Against Division of West Bank Into 'Bantustans'". Haaretz. 6 June 2004.

- Primor, Avi (18 September 2002). "Sharon's South African strategy". Haaretz.

- Rahnema, Saeed (6 October 2014). "Gaza and the West Bank: Israel's two approaches and Palestinians' two bleak choices". Open Canada, Canadian International Council.

- Ram, Haggai (2009). Iranophobia: The Logic of an Israeli Obsession. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-77119-1.

- Raz, Avi (2020). "Dodging the Peril of Peace: Israelk and the Arabs in the Aftermath of the 1967 War". In Hanssen, Jens; Ghazal, Amal N. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle-Eastern and North African History. Oxford University Press. pp. 269–291. ISBN 978-0-199-67253-0.

- Report of the independent international fact-finding mission to investigate the implications of the Israeli settlements on the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of the Palestinian people throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem (PDF) (Report). UNHCR. 7 February 2013. pp. 6–7.

- Roy, Sara (2004). "The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict and Palestinian Socioeconomic Decline: A Place Denied". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 17 (3): 365–403. doi:10.1023/B:IJPS.0000019609.37719.99. JSTOR 20007687. S2CID 145653769.

- Sabel, Robbie (Fall 2011). "The Campaign to Delegitimize Israel with the False Charge of Apartheid". Jewish Political Studies Review. 23 (3/4): 18–31. JSTOR 41575857.

- Shain, Milton (2019). "The Roots of Anti-Zionism in South Africa and the Delegitimization of Israel". In Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (ed.). Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: The Dynamics of Delegitimization. Indiana University Press. pp. 397–413. ISBN 978-0-253-03874-6.

- Shalev, Chemi (6 June 2017). "Netanyahu's Blueprint for a Palestinian Bantustan". Haaretz.

- Shaul, Yehuda (11 February 2020). "Trump's Middle East Peace Plan Isn't New. It Plagiarized a 40-Year-Old Israeli Initiative". Foreign Policy.

- Slater, Jerome (2001). "What Went Wrong? The Collapse of the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process". Political Science Quarterly. 116 (2): 171–199. doi:10.2307/798058. JSTOR 798058.

- Slater, Jerome (2020). Mythologies Without End: The US, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019045908-6.

- Srivastava, Mehul (17 June 2020). "Israel's annexation plan: the 'existential threat' to Palestinian dreams". Financial Times.

- Stephens, Philip (21 February 2013). "Settler policy imperils Israel's foundations". Financial Times.

- Taraki, Lisa (Summer 2008). "Enclave Micropolis: The Paradoxical Case of Ramallah/Al-Bireh" (PDF). Journal of Palestine Studies. 37 (4): 6–20. doi:10.1525/jps.2008.37.4.6.

- Thrall, Nathan (2017). The Only Language They Understand: Forcing Compromise in Israel and Palestine. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-62779-710-8.

- Toynbee, Arnold (January 1931). "The Present Situation in Palestine". International Affairs. 10 (1): 38–68. doi:10.2307/3015929. JSTOR 3015929.

- Weizman, Eyal (7 August 2012). Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-868-6.

- Yiftachel, Oren (2016). "Between One and Two: Apartheid or Confederation for Israel/Palestine?". In Ehrenberg, John; Peled, Yoav (eds.). Israel and Palestine: Alternative Perspectives on Statehood. Rowman and Littlefield. pp. 305–336. ISBN 978-1-442-24508-2.

- Ziegler, Jean (31 October 2003). "The right to food Report by the Special Rapporteur, Jean Ziegler Addendum Mission to the Occupied Palestinian Territories". United Nations.