This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Pink Saffron (talk | contribs) at 17:02, 26 February 2021 (→Types and structure). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:02, 26 February 2021 by Pink Saffron (talk | contribs) (→Types and structure)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Gang (disambiguation). Violent group of individuals "Street gang", "Crime gang", and "Gang culture" redirect here. For the Sesame Street book, see Street Gang. For similar term, see criminal gang. For the Ice-T album, see Gang Culture (album).This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A gang is a group or society of associates, friends or members of a family with a defined leadership and internal organization that identifies with or claims control over territory in a community and engages, either individually or collectively, in illegal, and possibly violent, behavior. Gangs arose in America by the middle of the nineteenth century and were a concern for city leaders from the time they appeared. Some members of criminal gangs are "jumped in" (by going through a process of initiation), or have to prove their loyalty and right to belong by committing certain acts, usually theft or violence. A member of a gang may be called a "gangster".

A number of gangs have gained notoriety in the course of history, including the Sicilian Mafia, Italian-American Mafia, and various other Italian organized crime groups, such as the Camorra; the Russian mafia, the Albanian mafia, the Irish Mob, the D-Company, various organizations within the French underworld, particularly Corsican mafia groups such as Unione Corse and the Gang de la Brise de Mer; British Firms, the Jewish Mob, the Greek mafia, the Nigerian mafia, Triads, the Yakuza, the Jamaican posse and Yardie gangs; the African-American Bloods and Crips; the Armenian Mob; Latin American gangs such as the Colombian drug cartels, Mexican mafia, the Latin Kings, MS-13, Norteños and Sureños; white supremacist gangs such as the Aryan Brotherhood and Aryan Nations; and outlaw biker gangs like Hells Angels,the Ku Klux Klan and Comanchero.

Definition

The word "gang" derives from the past participle of Old English gan, meaning "to go". It is cognate with Old Norse gangr, meaning "journey." It typically means a group of people, and may have neutral, positive or negative connotations depending on usage.

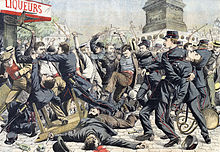

History

In discussing the banditry in American history Barrington Moore, Jr. suggests that gangsterism as a "form of self-help which victimizes others" may appear in societies which lack strong "forces of law and order"; he characterizes European feudalism as "mainly gangsterism that had become society itself and acquired respectability through the notions of chivalry".

A wide variety of gangs, such as the Order of Assassins, the Damned Crew, Adam the Leper's gang, Penny Mobs, Chinese Triads, Snakehead, Japanese Yakuza, the Irish Mob, Pancho Villa's Villistas, Dead Rabbits, American Old West outlaw gangs, Bowery Boys, Chasers, the Italian Mafia, Jewish mafia, and Russian mafia crime families have existed for centuries.

The 17th century saw London "terrorized by a series of organized gangs", some of them known as the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, and Dead Boys. These gangs often came into conflict with each other. Members dressed "with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions."

Chicago had over 1,000 gangs in the 1920s. These early gangs had reputations for many criminal activities, but in most countries could not profit from drug trafficking prior to drugs being made illegal by laws such as the 1912 International Opium Convention and the 1919 Volstead Act. Gang involvement in drug trafficking increased during the 1970s and 1980s, but some gangs continue to have minimal involvement in the trade.

In the United States, the history of gangs began on the East Coast in 1783 following the American Revolution. The emergence of the gangs was largely attributed to the vast rural population immigration to the urban areas. The first street-gang in the United States, the 40 Thieves, began around the late 1820s in New York City. The gangs in Washington D.C. had control of what is now Federal Triangle, in a region then known as Murder Bay.

Current numbers

Further information: Gang population

In 2007, there were approximately 786,000 active street gang members in the United States, according to the National Youth Gang Center. In 2011, the National Gang Intelligence Center of the Federal Bureau of Investigation asserted that "There are approximately 1.4 million active street, prison, and outlaw gang members comprising more than 33,501 gangs in the United States." Approximately 230,000 gang members were in U.S. prisons or jails in 2011.

According to the Chicago Crime Commission publication, "The Gang Book 2012", Chicago has the highest number of gang members of any city in the United States: 150,000 members. Traditionally Los Angeles County has been considered the Gang Capital of America, with an estimated 120,000 (41,000 in the City) gang members.

There were at least 30,000 gangs and 800,000 gang members active across the US in 2007. About 900,000 gang members lived "within local communities across the country," and about 147,000 were in U.S. prisons or jails in 2009. By 1999, Hispanics accounted for 47% of all gang members, Blacks 31%, Whites 13%, and Asians 7%.

On December 13, 2009, The New York Times published an article about growing gang violence on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and estimated that there were 39 gangs with 5,000 members on that reservation alone.

There are between 25,000 and 50,000 gang members in Central America's El Salvador.

The FBI estimates that the four Italian organized crime groups active in the United States have 25,000 members in total.

The Russian, Chechen, Azerbaijani, Ukrainian, Georgian, Armenian, and other former Soviet organized crime groups or "Bratvas" have many members and associates affiliated with their various sorts of organized crime, but no statistics are available.

The Yakuza are one of the largest criminal organizations in the world. As of 2005, there are some 102,400 known members in Japan.

Hong Kong's Triads include up to 160,000 members in the 21st century. It was estimated that in the 1950s, there were 300,000 Triad members in Hong Kong.

Notable examples

See also: List of gangs in the United States

Perhaps one of the most infamous criminal gangs are the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and the Italian-American Mafia. The Neapolitan Camorra, the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta and the Apulian Sacra Corona Unita are similar Italian organized gangs.

Other criminal gangs include the Russian mafia, Mexican, Colombian Drug Cartels, the Aryan Brotherhood, the Mexican Mafia, the Texas Syndicate, the Black Guerrilla Family, the Nuestra Familia, the Mara Salvatrucha, the Primeiro Comando da Capital, the Irish Mob, the Puerto Rican Mafia, Nuestra familia, the Chinese Triads, the Japanese Yakuza, the Jamaican-British Yardies, the Haitian gang Zoe Pound, and other crime syndicates.

On a lower level in the hierarchy of criminal gangs are street gangs in the United States (mostly branches of larger criminal gangs). Examples include:

- Black gangs like the Bloods and the Crips, also the Vice Lords and the Gangster Disciples

- National origin and/or racial gangs like the Trinitario, Sureños, Tiny Rascal Gang, Asian Boyz, Wa Ching, The Latin Kings, The Hammerskins, Nazi Lowriders and Blood & Honour.

- Biker gangs such as the Hells Angels, the Pagans, the Outlaws, and the Bandidos, known as the "Big Four".

Types and structure

Many types of gangs make up the general structure of an organized group.

There are street gangs, with members of similar background and motivations. The term "street gang" is commonly used interchangeably with "youth gang", referring to neighborhood or street-based youth groups that meet "gang" criteria. Miller (1992) defines a street gang as "a self-formed association of peers, united by mutual interests, with identifiable leadership and internal organization, who act collectively or as individuals to achieve specific purposes, including the conduct of illegal activity and control of a particular territory, facility, or enterprise."

Understanding the structure of gangs is a critical skill to defining the types of strategies that are most effective with dealing with them, from the at-risk youth to the gang leaders. Not all individuals who display the outward signs of gang membership are actually involved in criminal activities. An individual's age, physical structure, ability to fight, willingness to commit violence, and arrest record are often principal factors in determining where an individual stands in the gang hierarchy; now money derived from criminal activity and ability to provide for the gang also impacts the individual's status within the gang. The structure of gangs varies depending primarily on size, which can range from five or ten to thousands. Many of the larger gangs break up into smaller groups, cliques or sub-sets (these smaller groups can be called "sets" in gang slang.) The cliques typically bring more territory to a gang as they expand and recruit new members. Most gangs operate informally with leadership falling to whomever takes control; others have distinct leadership and are highly structured, which resembles more or less a business or corporation.

Prison gangs are groups in prison or correctional institutions for mutual protection and advancement. Prison gangs often have several "affiliates" or "chapters" in different state prison systems that branch out due to the movement or transfer of their members. The 2005 study neither War nor Peace: International Comparisons of Children and Youth in Organized Armed Violence studied ten cities worldwide and found that in eight of them, "street gangs had strong links to prison gangs". According to criminal justice professor John Hagedorn, many of the biggest gangs from Chicago originated from prisons. From the St. Charles Illinois Youth Center originated the Conservative Vice Lords and Blackstone Rangers. Although the majority of gang leaders from Chicago are now incarcerated, most of those leaders continue to manage their gangs from within prison.

Criminal gangs may function both inside and outside of prison, such as the Nuestra Familia, Mexican Mafia, Folk Nation, and the Brazilian PCC. During the 1970s, prison gangs in Cape Town, South Africa began recruiting street gang members from outside and helped increase associations between prison and street gangs. In the US, the prison gang the Aryan Brotherhood is involved in organized crime outside of prison.

Involvement

Matthew O'Deane has identified five primary steps of gang involvement applicable to the majority of gangs in the world; at risk, associates, members, hardcore members, and leaders.

Gang leaders are the upper echelons of the gang's command. This gang member is probably the oldest in the posse, likely has the smallest criminal record, and they often have the power to direct the gang's activity, whether they are involved or not. In many jurisdictions, this person is likely a prison gang member calling the shots from within the prison system or is on parole. Often, they distance themselves from the street gang activities and make attempts to appear legitimate, possibly operating a business that they run as a front for the gang's drug dealing or other illegal operations.

Membership

The numerous push factors experienced by at-risk individuals vary situationally, but follow a common theme of the desire for power, respect, money, and protection. These desires are very influential in attracting individuals to join gangs, and their influence is particularly strong on at-risk youth. Such individuals are often experiencing low levels of these various factors in their own lives, feeling ostracized from their community and lacking social support. Joining a gang may appear to them to be the only way to obtain status and success; they may feel that "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em". Upon joining a gang, they instantly gain a feeling of belonging and identity; they are surrounded with individuals whom they can relate to. They have generally grown up in the same area as one another and can bond over similar needs. In some areas, joining a gang is an integrated part of the growing-up process.

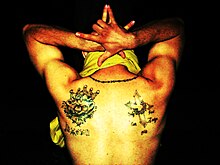

Gang membership is generally maintained by gangs as a lifetime commitment, reinforced through identification such as tattoos, and ensured through intimidation and coercion. Gang defectors are often subject to retaliation from the deserted gang. Many gangs, including foreign and transnational gangs, hold that the only way to leave the gang is through death. This is sometimes informally called the "morgue rule".

Gang membership represents the phenomenon of a chronic group criminal spin; accordingly, the criminality of members is greater when they belong to the gang than when they are not in the gang—either before or after being in the gang. In addition, when together, the gang criminality as a whole is greater than that of its members when they are alone. The gang operates as a whole greater than its parts and influences the behavior of its members in the direction of greater extend and stronger degree of criminality.

Some states have a formal process to establish that a person is a member of a gang, called validation. Once a person is validated as a gang member, the person is subject to increased sentences, harsher punishments (such as solitary confinement) and more restrictive parole rules. To validate a person as a gang member, the officials generally must provide evidence of several factors, such as tattoos, photographs, admissions, clothing, etc. The legal requirements for validating a person are much lower than the requirements for convicting of a crime.

Non-member women in gang culture

Women associated with gangs but who lack membership are typically categorized based on their relation to gang members. A survey of Mexican American gang members and associates defined these categories as girlfriends, hoodrats, good girls, and relatives. Girlfriends are long-term partners of male gang members, and may have children with them. "Hoodrats" are seen as being promiscuous and heavy drug and alcohol users. Gang members may engage in casual sex with these girls, but they are not viewed as potential long-term partners and are severely stigmatized by both men and women in gang culture. "Good girls" are long-term friends of members, often from childhood, and relatives are typically sisters or cousins. These are fluid categories, and women often change status as they move between them. Valdez found that women with ties to gang members are often used to hold illegal weapons and drugs, typically, because members believe the girls are less likely to be searched by police for such items.

Typical activities

The United Nations estimates that gangs make most of their money through the drugs trade, which is thought to be worth $352 billion in total. The United States Department of Justice estimates there are approximately 30,000 gangs, with 760,000 members, impacting 2,500 communities across the United States.

Gangs are involved in all areas of street-crime activities like extortion, drug trafficking, both in and outside the prison system, and theft. Gangs also victimize individuals by robbery and kidnapping. Cocaine is the primary drug of distribution by gangs in America, which have used the cities Chicago, Cape Town, and Rio de Janeiro to transport drugs internationally. Brazilian urbanization has driven the drug trade to the favelas of Rio. Often, gangs hire "lookouts" to warn members of upcoming law enforcement. The dense environments of favelas in Rio and public housing projects in Chicago have helped gang members hide from police easily.

Street gangs take over territory or "turf" in a particular city and are often involved in "providing protection", often a thin cover for extortion, as the "protection" is usually from the gang itself, or in other criminal activity. Many gangs use fronts to demonstrate influence and gain revenue in a particular area.

Gang violence

Gang violence refers mostly to the illegal and non-political acts of violence perpetrated by gangs against civilians, other gangs, law enforcement officers, firefighters, or military personnel. Throughout history, such acts have been committed by gangs at all levels of organization. Modern gangs introduced new acts of violence, which may also function as a rite of passage for new gang members.

In 2006, 58 percent of L.A.'s murders were gang-related. Reports of gang-related homicides are concentrated mostly in the largest cities in the United States, where there are long-standing and persistent gang problems and a greater number of documented gang members—most of whom are identified by law enforcement.

Gang-related activity and violence has increased along the U.S. Southwest border region, as US-based gangs act as enforcers for Mexican drug cartels.

A gang war is a type of small war that occurs when two gangs end up in a feud over territory.

Gang violence in schools

Despite gangs usually formed in the community, not specifically in schools, gang violence can potentially affect schools in different ways including:

- Gangs can recruit members in schools;

- Gang members from the same school can engage in violence on the school premises or around their school;

- Gang members from the same school can commit violence against other students in the same school who belong to a different gang or who do not belong to a gang;

- Gangs may commit violence against other schools and students in the community where they are active, even if these students do not belong to a gang.

Global data on the prevalence of these different forms of gang violence in and around schools is limited. However, available evidence suggests that gang violence is more common in schools where students are exposed to other forms of community violence and where they fear violence at school.

Children who grow up in neighbourhoods with high levels of crime has been identified as a risk factor for youth violence, including gang violence. According to studies, children who knew many adult criminals were more likely to engage in violent behaviour by the age of 18 years than those who did not.

Gang violence is often associated with carrying weapons, including in school. A study of 10-19-year-olds in the UK found that 44% of those who reported belonging to a delinquent youth group had committed violence and 13% had carried a knife in the previous 12 months versus 17% and 4% respectively among those who were not in such a group.

According to a meta-analysis of 14 countries in North America, Europe, the Middle East, Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific also showed that carrying a weapon at school is associated with bullying victimization.

Comparison of Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) data on school violence and bullying for countries that are particularly affected by gang violence suggests that the links may be limited. In El Salvador and Guatemala, for example, where gang violence is a serious problem, GSHS data show that the prevalence of bullying, physical fights and physical attacks reported by school students is relatively low, and is similar to prevalence in other countries in Central America where gang violence is less prevalent.

Sexual violence

Women in gang culture are often in environments where sexual assault is common and considered to be a norm. Women who attend social gatherings and parties with heavy drug and alcohol use are particularly likely to be assaulted. A girl who becomes intoxicated and flirts with men is often seen as "asking for it" and is written off as a "hoe" by men and women. "Hoodrats" and girls associated with rival gangs have lower status at these social events, and are victimized when members view them as fair game and other women rationalize assault against them.

Motives

Most modern research on gangs has focused on the thesis of class struggle following the work of Walter B. Miller and Irving Spergel. In this body of work The Gaylords are cited as the prime example of an American gang that is neither Black nor Hispanic. Some researchers have focused on ethnic factors. Frederic Thrasher, who was a pioneer of gang research, identified "demoralization" as a standard characteristic of gangs. John Hagedorn has argued that this is one of three concepts that shed light on patterns of organization in oppressed racial, religious and ethnic groups (the other two are Manuel Castells' theory of "resistance identity and Derrick Bell's work on the permanence of racism).

Usually, gangs have gained the most control in poorer, urban communities and developing countries in response to unemployment and other services. Social disorganization, and the disintegration of societal institutions such as family, school, and the public safety net, enable groups of peers to form gangs. According to surveys conducted internationally by the World Bank for their World Development Report 2011, by far the most common reason people suggest as a motive for joining gangs is unemployment.

Ethnic solidarity is a common factor in gangs. Black and Hispanic gangs formed during the 1960s in the USA often adapted nationalist rhetoric. Both majority and minority races in society have established gangs in the name of identity: the Igbo gang Bakassi Boys in Nigeria defend the majority Igbo group violently and through terror, and in the United States, whites who feel threatened by minorities have formed their own gangs, such as the Ku Klux Klan. Responding to an increasing black and Hispanic migration, a white gang formed called Chicago Gaylords. Some gang members are motivated by religion, as is the case with the Muslim Patrol and the Epstein-Wolmark gang.

Identification

Main article: Gang signal| This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Misplaced Pages. See Misplaced Pages's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (September 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Most gang members have identifying characteristics which are unique to their specific clique or gang. The Bloods, for instance, wear red bandanas, the Crips blue, allowing these gangs to "represent" their affiliation. Any disrespect of a gang member's color by an unaffiliated individual is regarded as grounds for violent retaliation, often by multiple members of the offended gang. Tattoos are also common identifiers, such as an '18' above the eyebrow to identify a member of the 18th Street gang. Tattoos help a gang member gain respect within their group, and mark them as members for life. Tattoos can also represent the level they are in the gang, being that certain tattoos can mean they are a more accomplished member. The accomplishments can be related to doing an dangerous act that showed your loyalty to the gang. They can be burned on as well as inked. Some gangs make use of more than one identifier, like the Nortenos, who wear red bandanas and have "14", "XIV", "x4", and "Norte" tattoos.

Gangs often establish distinctive, characteristic identifiers including graffiti tags colors, hand signals, clothing (for example, the gangsta rap-type hoodies), jewelry, hair styles, fingernails, slogans, signs (such as the noose and the burning cross as the symbols of the Klan), flags secret greetings, slurs, or code words and other group-specific symbols associated with the gang's common beliefs, rituals, and mythologies to define and differentiate themselves from other groups and gangs.

As an alternative language, hand-signals, symbols, and slurs in speech, graffiti, print, music, or other mediums communicate specific informational cues used to threaten, disparage, taunt, harass, intimidate, alarm, influence, or exact specific responses including obedience, submission, fear, or terror. One study focused on terrorism and symbols states that "ymbolism is important because it plays a part in impelling the terrorist to act and then in defining the targets of their actions." Displaying a gang sign, such as the noose, as a symbolic act can be construed as "a threat to commit violence communicated with the intent to terrorize another, to cause evacuation of a building, or to cause serious public inconvenience, in reckless disregard of the risk of causing such terror or inconvenience … an offense against property or involving danger to another person that may include but is not limited to recklessly endangering another person, harassment, stalking, ethnic intimidation, and criminal mischief."

The Internet is one of the most significant media used by gangs to communicate in terms of the size of the audience they can reach with minimal effort and reduced risk. The Internet provides a forum for recruitment activities, typically provoking rival gangs through derogatory postings, and to glorify their gang and themselves. Gangs use the Internet to communicate with each other, facilitate criminal activity, spread their message and culture around the nation. As Internet pages like YouTube, Twitter and Facebook become more popular, law enforcement works to understand how to conduct investigations related to gang activity in an online environment. In most cases the police can and will get the information they need, however this requires police officers and federal agents to make formal legal requests for information in a timely manner, which typically requires a search warrant or subpoena to compel the service providers to supply the needed information. A grand jury subpoena or administrative subpoena, court order, search warrant; or user consent is needed to get this information pursuant to the Electronic Communication Privacy Act, Title 18 U.S.C. § 2701, et seq. (ECPA). Most gang members have personal web pages or some type of social networking internet account or chat room where they post photos and videos and talk openly about their gang exploits. The majority of the service providers that gang members use are free social networking sites that allow users to create their own profile pages, which can include lists of their favorite musicians, books and movies, photos of themselves and friends, and links to related web pages. Many of these services also permit users to send and receive private messages and talk in private chat rooms. Often a police officer may stumble upon one of these pages, or an informant can give access to the local gang page. Alternatively, they will have to formally request the needed information. Most service providers have four basic types of information about their users that may be relevant to a criminal investigation; 1) basic identity/subscriber information supplied by the user in creating the account; 2) IP log-in information; 3) files stored in a user's profile (such as "about me" information or lists of friends); and 4) user sent and received message content. It is important to know the law, and understand what the police can get service providers to do and what their capabilities are. It is also important to understand how gang members use the Internet and how the police can use their desire to be recognized and respected in their sub-culture against them.

Debate surrounding impact

In the UK context, law enforcement agencies are increasingly focusing enforcement efforts on gangs and gang membership. However debate persists over the extent and nature of gang activity in the UK, with some academics and policy-makers arguing that the current focus is inadvisable, given a lack of consensus over the relationship between gangs and crime.

The Runnymede Trust suggests that, despite the well-rehearsed public discourse around youth gangs and "gang culture", "We actually know very little about 'gangs' in the UK: about how 'a gang' might be defined or understood, about what being in 'a gang' means... We know still less about how 'the gang' links to levels of youth violence."

Professor Simon Hallsworth argues that, where they exist, gangs in the UK are "far more fluid, volatile and amorphous than the myth of the organized group with a corporate structure". This assertion is supported by a field study conducted by Manchester University, which found that "most within- and between-gang disputes... emanated from interpersonal disputes regarding friends, family and romantic relationships", as opposed to territorial rivalries, and that criminal enterprises were "rarely gang-coordinated... most involved gang members operating as individuals or in small groups."

Cottrell-Boyce, writing in the Youth Justice journal, argues that gangs have been constructed as a "suitable enemy" by politicians and the media, obscuring the wider, structural roots of youth violence. At the level of enforcement, a focus on gang membership may be counterproductive; creating confusion and resulting in a drag-net approach which can criminalise innocent young people rather than focusing resources on serious violent crime.

Gang membership in the US military

Main article: Gang presence in the United States militaryGang members in uniform use their military knowledge, skills and weapons to commit and facilitate various crimes. As of April 2011, the NGIC has identified members of at least 53 gangs whose members have served in or are affiliated with US military.

In 2006, Scott Barfield, a Defense Department investigator, said there is an online network of gangs and extremists: "They're communicating with each other about weapons, about recruiting, about keeping their identities secret, about organizing within the military."

A 2006 Sun-Times article reports that gangs encourage members to enter the military to learn urban warfare techniques to teach other gang members. A January 2007 article in the Chicago Sun-Times reported that gang members in the military are involved in the theft and sale of military weapons, ammunition, and equipment, including body armor. The Sun-Times began investigating the gang activity in the military after receiving photos of gang graffiti showing up in Iraq.

The FBI's 2007 report on gang membership in the military states that the military's recruit screening process is ineffective, allows gang members/extremists to enter the military, and lists at least eight instances in the last three years in which gang members have obtained military weapons for their illegal enterprises. "Gang Activity in the U.S. Armed Forces Increasing", dated January 12, 2007, states that street gangs including the Bloods, Crips, Black Disciples, Gangster Disciples, Hells Angels, Latin Kings, The 18th Street Gang, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), Mexican Mafia, Norteños, Sureños, and Vice Lords have been documented on military installations both domestic and international although recruiting gang members violates military regulations.

See also

- Collective narcissism

- Criminal tattoo

- Drug cartel

- Gang population

- Gangs in Australia

- Gangs in Canada

- Gangs in New Zealand

- Gangs in South Africa

- Gangs in the United Kingdom

- Gangs in the United States

- List of criminal enterprises, gangs, and syndicates

- List of known gang members

- Malcolm W. Klein

- Organized crime

- Outlaw motorcycle club

- Raskol gangs

- School violence

- Triad (organized crime)

- Violent extremism

- Violent non-state actor

- War on Gangs

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying, 70, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying, 70, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 279.

- Douglas Harper. "gang". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Cleasby/Vigfusson An Icelandic-English Dictionary (1874); GÖNGUDRYKKJA -- GARÐR

- "Gabg". dictionary.com.

- "Hi, gang! (used with friends)". wordreference.com.

- Caspar Walsh (10 November 2011). "Gangs are good for society". theguardian.com.

-

Moore, Barrington (March 1967) . Social origins of dictatorship and democracy: Lord and peasant in the making of the modern world. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 214.

Gangsterism is likely to crop up wherever the forces of law and order are weak. European feudalism was mainly gangsterism that had become society itself and acquired respectability through the notions of chivalry. As the rise of feudalism out of the decay of the Roman administrative system shows, this form of self-help which victimizes others is in principle opposed to the workings of a sound bureaucratic system.

-

Howell, James C. (2012). Gangs in America's Communities. SAGE. ISBN 9781412979535.

gangs in america's communities.

-

Howell, James C. (2012). Gangs in America's Communities. SAGE. ISBN 9781412979535.

gangs in america's communities.

- Gang (crime). Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "The Growth of Youth Gang Problems in the United States: 1970-98". 2001.

-

Howell, James C. (2012). Gangs in America's Communities. SAGE. ISBN 9781412979535.

gangs in america's communities.

- Savage, Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape, 2009, p. 100-101; Gutheim and Lee, p. 73; Lowry, p. 61-65; Evelyn, Dickson, and Ackerman, pp. 63-64.

- ^ Archived January 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FBI — 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment – Emerging Trends. Fbi.gov.

- "Chicago Most Infested City in U.S., Officials Say". NBC Chicago. 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- Paul Harris (2007-03-18). "Gang mayhem grips LA". London: Observer.guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "COPS Office: Gangs". Cops.usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- L.A. Gangs: Nine Miles and Spreading Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Laweekly.com. December 13, 2007.

- Report: Gang membership on the rise across U.S., by Kevin Johnson, USA Today, January 30, 2009

- Egley, Arlen Jr. (November 2000). "Highlights of the 1999 National Youth Gang Survey" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Indian Gangs Grow, Bringing Fear and Violence to Reservation". The New York Times. December 13, 2009

- "El Salvador's teenage beauty queens live and die by gang law", The Observer, November 10, 2002

- "Italian Organized Crime—Overview" Archived October 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. FBI.gov.

- Criminal Investigation: Fight Against Organized Crime (1), Overview of Japanese Police, National Police Agency (June 2007).

- Asian Triads Archived February 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Hong Kong's T-Shirt Contest. TIME. November 28, 2007.

- "Introduction to the Mafia". source. Archived from the original on 2016-01-02.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew M.; Bailey, John (2009-07-20). "Evade, Corrupt, or Confront? Organized Crime and the State in Brazil and Mexico". Journal of Politics in Latin America. 1 (2): 3–29. doi:10.1177/1866802X0900100201. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- "ORGANISED CRIME AROUND THE WORLD" (PDF). The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-16.

- FBI Safe Street Violent Crime Initiative - Report Fiscal Year 2000- FBI.org

- 2004 Annual Report Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine- Criminal Intelligence Service Canada, cisc.gc.ca

- Motorcycle Gangs Archived August 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine- Connecticut Gang Investigators Association

- "Street Gang Dynamics". The Nawojczyk Group, Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-08-18.

- "general structure" (PDF). source.

- Miller, W.B. 1992 (Revised from 1982). Crime by Youth Gangs and Groups in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of JusticePrograms, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Matthew O'Deane. "gang". Gangs: Theory, Practice and Research. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Engber, Daniel (2005-12-13). "How do you start a gang?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- "Societal and Correctional Context of Prison Gangs" (PDF). source. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-15.

- ^ Hagedorn 2008, p. 12

- Hagedorn 2008, p. 13

- O'Deane, Matthew (2012). Gang Injunctions and Abatement: Using Civil Remedies to Curb Gang-Related Crimes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 9781466554108.

- Matthew O'Deane. Gang Investigator's Handbook: A Law-Enforcement Guide to Identifying and Combating Violent Street Gangs.

- O'Grady. 2007. Crime in a Canadian context.

- Brenneman, Robert (November 23, 2011). Homies and Hermanos: God and Gangs in Central America. 198 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016 USA: Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780199753901.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Ronel, N. (2011). "Criminal behavior, criminal mind: Being caught in a criminal spin." 'International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(8), 1208–1233

- "Membership Validation Criteria". 15 May 2014.

- Wood, Graeme. "How Gangs Took Over Prisons".

- "Roseville police explain gang validation process".

- "Report". dconc.gov.

- ^ Valdez, A. (2007). Mexican American Girls and Gang Violence. New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Syal, Rajeev (December 13, 2009). "Drug money saved banks in global crisis, claims UN advisor". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- "Highlights of the 2004 National Youth gang Survey" (PDF). Ncjrs.gov. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- "Organized_crime". source. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30.

- Hagedorn 2008, p. 14

- Hagedorn 2008, pp. 14–15

- "Gang influence and gain revenue" (PDF). source. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-24.

- "ICE and Local Law Enforcement Target Immigrant Gangs". source.

- "U.S. Gangs: Their Changing History" (PDF). data. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-24.

- Vigil, James Diego (2003). "Urban Violence and Street Gangs". Annual Review of Anthropology. 32: 225–242. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093426.

- "L.A.'S New Gang War". Newsweek. January 25, 2007

- "Frequently Asked Questions About Gangs". National Gang Center.

- ^ Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying. UNESCO. 2019. ISBN 978-92-3-100306-6.

- ^ United Nations (UN) Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence Against Children. (2016). Protecting Children Affected by Armed Violence in the Community. New York: UN: United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-101345-0.

- Krug E., Dahlberg L., Mercy J. (2002). "World Report on Violence and Health". Geneva: WHO.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization (WHO) (2015). Preventing youth violence: an overview of the evidence. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-150925-1.

- Sharp, C., Aldridge, J. and Medina, J. "Delinquent youth groups and offending behaviour: findings from the 2004 Offending, Crime and Justice Survey". Home Office Online Report 14/06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Valdebenito Munoz, S., Ttofi, M., Eisner, M., & Gaffney, H. "Weapon carrying in and out of school among pure bullies, pure victims and bully-victims: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies". Aggression and Violent Behavior: 33, pp. 62–77.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hagedorn 2008, p. 55

- Hagedorn 2008, p. 7

- Hagedorn 2008, p. 6

- 2011 World Development Report See Figure F2.2 on page 35

- Hagedorn 2008, p. 16

- Hagedorn 2008, pp. 53–54

- Shaer, Matthew (September 2, 2014) "Epstein Orthodox Hit Squad", GQ. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- "Gang Awareness". Everett Police Department. Archived from the original on 2015-04-23.

- "Gang Identifiers". Winston-Salem Police Department web site "TGOD Mofo" is a common statement being passed around the hood. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- "Graffiti and Other Gang Identifiers". © 2002 Michael K. Carlie. Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- Author: Ferrell, J., Title: "Crimes of style: Urban graffiti and the politics of criminality Archived 2007-11-10 at the Wayback Machine", Publisher: New York: Garland. (235pp), Year: 1993

- "Gang Identifiers and Terminology", Cantrell, Mary Lynn, Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Problems, v1 n1 pp13-14 Spr 1992

- "Noose: 'Shameful' sign makes ominous return Archived July 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine", by Darryl Fears, Washington Post, Published: October 21, 2007 6:00 a.m.

- Cerulo, Karen A. (1993). "Symbols and the world system: National anthems and flags". Sociological Forum. 8 (2): 243–271. doi:10.1007/BF01115492. S2CID 144023960.

- "The Seven-Stage Hate Model Archived 2010-04-10 at the Wayback Machine", United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation

- "RICO". Definitions.uslegal.com. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- "Symbolism and Sacrifice in Terrorism", Authors: J. Dingley; M. Kirk-Smith, Source: Small Wars & Insurgencies, Volume 13, Number 1, Spring 2002, pp. 102-128(27, Publisher: Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group

- "Terroristic Threat Law & Legal Definition". Definitions.uslegal.com. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ Combating Gangsters Online Archived 2014-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, Author: Matthew O'Deane, April 2011, pp. 1-7, Publisher: Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Goldson, Barry (2011). Youth in Crisis? Gangs, Territoriality and Violence. London: Routledge. p. 9.

- ^ Cottrell-Boyce, Joe (December 2013). "Ending Gang and Youth Violence: A Critique". Youth Justice. 13 (3): 193–206. doi:10.1177/1473225413505382. S2CID 147163053.

- Runnymede Trust. "(Re)thinking Gangs" (PDF). Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- New York Times - Hate Groups Are Infiltrating the Military, Group Asserts

- CBS2Chicago Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine - Chicago Gang Graffiti Showing Up In Iraq

- Stars and Stripes - Army defends recruit screening process

- Intelligence Assessment - Gang-Related Activity in the US Armed Forces Increasing

Bibliography

- Hagedorn, John M. (2008), A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States: University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-5066-8

- O'Deane, Matthew D. (2010), Gangs: Theory, Practice and Research, San Clemente, California, United States: Lawtechcustompublishing.com, ISBN 978-1-933778-19-8, archived from the original on 2016-03-05, retrieved 2011-05-07

- Anon. 2018. “Gangs from Different Sociological Perspectives and Theories.” UKEssays.com. Retrieved October 30, 2019 ).

- Collins, Angela M., Scott Menard and David Pyrooz. 2018. "Collective Behavior and the Generality of Integrated Theory: A National Study of Gang Fighting." Deviant Behavior 39(8):992-1005

External links

![]() Media related to Gangs (organized crime) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gangs (organized crime) at Wikimedia Commons

| Gangs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| List of criminal enterprises, gangs and syndicates | |||

| Aspects and components |

| ||

| Types | |||

| By location | |||

| Financial regulation | |||