This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Ceoil (talk | contribs) at 17:43, 27 February 2022 (Undid revision 1074326034 by 174.247.193.19 (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:43, 27 February 2022 by Ceoil (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 1074326034 by 174.247.193.19 (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Latin sequence, liturgical hymn For other uses, see Dies irae (disambiguation).

"Dies irae" (Template:IPA-la; "the Day of Wrath") is a Latin sequence attributed to either Thomas of Celano of the Franciscans (1200–1265) or to Latino Malabranca Orsini (d. 1294), lector at the Dominican studium at Santa Sabina, the forerunner of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (the Angelicum) in Rome. The sequence dates from the 13th century at the latest, though it is possible that it is much older, with some sources ascribing its origin to St. Gregory the Great (d. 604), Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), or Bonaventure (1221–1274).

It is a medieval Latin poem characterized by its accentual stress and rhymed lines. The metre is trochaic. The poem describes the Last Judgment, trumpet summoning souls before the throne of God, where the saved will be delivered and the unsaved cast into eternal flames.

It is best known from its use in the Roman Rite Requiem (Mass for the Dead or Funeral Mass). An English version is found in various Anglican Communion service books.

The first melody set to these words, a Gregorian chant, is one of the most quoted in musical literature, appearing in the works of many composers. The final couplet, "Pie Jesu", has been often reused as an independent song.

Use in the Roman liturgy

The "Dies irae" has been used in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite liturgy as the sequence for the Requiem Mass for centuries, as made evident by the important place it holds in musical settings such as those by Mozart and Verdi. It appears in the Roman Missal of 1962, the last edition before the implementation of the revisions that occurred after the Second Vatican Council. As such, it is still heard in churches where the Tridentine Latin liturgy is celebrated. It also formed part of the pre-conciliar liturgy of All Souls' Day.

In the reforms to the Catholic Church’s Latin liturgical rites ordered by the Second Vatican Council, the "Consilium for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Liturgy", the Vatican body charged with drafting and implementing the reforms (1969–70), eliminated the sequence as such from funerals and other Masses for the Dead. A leading figure in the post-conciliar liturgical reforms, Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, explains the rationale of the Consilium:

They got rid of texts that smacked of a negative spirituality inherited from the Middle Ages. Thus they removed such familiar and even beloved texts as "Libera me, Domine", "Dies irae", and others that overemphasized judgment, fear, and despair. These they replaced with texts urging Christian hope and arguably giving more effective expression to faith in the resurrection.

"Dies irae" remains as a hymn ad libitum in the Liturgy of the Hours during the last week before Advent, divided into three parts for the Office of Readings, Lauds and Vespers.

Text

The Latin text below is taken from the Requiem Mass in the 1962 Roman Missal. The first English version below, translated by William Josiah Irons in 1849, albeit from a slightly different Latin text, replicates the rhyme and metre of the original. This translation, edited for more conformance to the official Latin, is approved by the Catholic Church for use as the funeral Mass sequence in the liturgy of the Anglican ordinariate. The second English version is a more formal equivalence translation.

| Original | Approved adaptation | Formal equivalence | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

Dies iræ, dies illa, |

Day of wrath! O day of mourning! |

The day of wrath, that day, |

Because the last two stanzas differ markedly in structure from the preceding stanzas, some scholars consider them to be an addition made in order to suit the great poem for liturgical use. The penultimate stanza Lacrimosa discards the consistent scheme of rhyming triplets in favor of a pair of rhyming couplets. The last stanza Pie Iesu abandons rhyme for assonance, and, moreover, its lines are catalectic.

In the liturgical reforms of 1969–71, stanza 19 was deleted and the poem divided into three sections: 1–6 (for Office of Readings), 7–12 (for Lauds) and 13–18 (for Vespers). In addition "Qui Mariam absolvisti" in stanza 13 was replaced by "Peccatricem qui solvisti" so that that line would now mean, "You who absolved the sinful woman". This was because modern scholarship denies the common medieval identification of the woman taken in adultery with Mary Magdalene, so Mary could no longer be named in this verse. In addition, a doxology is given after stanzas 6, 12 and 18:

| Original | Approved adaptation | Formal equivalence |

|---|---|---|

|

O tu, Deus majestatis, |

O God of majesty |

You, God of majesty, |

Manuscript sources

The text of the sequence is found, with slight verbal variations, in a 13th century manuscript in the Biblioteca Nazionale at Naples. It is a Franciscan calendar missal that must date between 1253 and 1255 for it does not contain the name of Clare of Assisi, who was canonized in 1255, and whose name would have been inserted if the manuscript were of later date.

Inspiration

A major inspiration of the hymn seems to have come from the Vulgate translation of Zephaniah 1:15–16:

|

Dies iræ, dies illa, dies tribulationis et angustiæ, dies calamitatis et miseriæ, dies tenebrarum et caliginis, dies nebulæ et turbinis, dies tubæ et clangoris super civitates munitas et super angulos excelsos. |

That day is a day of wrath, a day of tribulation and distress, a day of calamity and misery, a day of darkness and obscurity, a day of clouds and whirlwinds, a day of the trumpet and alarm against the fenced cities, and against the high bulwarks. (Douay–Rheims Bible) |

Other images come from the Book of Revelation, such as Revelation 20:11–15 (the book from which the world will be judged), Matthew 25:31–46 (sheep and goats, right hand, contrast between the blessed and the accursed doomed to flames), 1 Thessalonians 4:16 (trumpet), 2 Peter 3:7 (heaven and earth burnt by fire), and Luke 21:26 ("men fainting with fear... they will see the Son of Man coming").

From the Jewish liturgy, the prayer Unetanneh Tokef appears to be related: "We shall ascribe holiness to this day, For it is awesome and terrible"; "the great trumpet is sounded", etc.

Other translations

A number of English translations of the poem have been written and proposed for liturgical use. A very loose Protestant version was made by John Newton; it opens:

Day of judgment! Day of wonders!

Hark! the trumpet's awful sound,

Louder than a thousand thunders,

Shakes the vast creation round!

How the summons will the sinner's heart confound!

Jan Kasprowicz, a Polish poet, wrote a hymn entitled "Dies irae" which describes the Judgment day. The first six lines (two stanzas) follow the original hymn's metre and rhyme structure, and the first stanza translates to "The trumpet will cast a wondrous sound".

The American writer Ambrose Bierce published a satiric version of the poem in his 1903 book Shapes of Clay, preserving the original metre but using humorous and sardonic language; for example, the second verse is rendered:

Ah! what terror shall be shaping

When the Judge the truth's undraping –

Cats from every bag escaping!

The Rev. Bernard Callan (1750–1804), an Irish priest and poet, translated it into Gaelic around 1800. His version is included in a Gaelic prayer book, The Spiritual Rose.

Literary references

- Walter Scott used the first two stanzas in the sixth canto of his narrative poem "The Lay of the Last Minstrel" (1805).

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used the first, the sixth and the seventh stanza of the hymn in the scene "Cathedral" in the first part of his drama Faust (1808).

- Oscar Wilde's "Sonnet on Hearing the Dies Irae Sung in the Sistine Chapel" (Poems, 1881), contrasts the "terrors of red flame and thundering" depicted in the hymn with images of "life and love".

- In Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera, Erik (the Phantom) has the chant displayed on the wall of his funereal bedroom.

- It is the inspiration for the title and major theme of the 1964 novel Deus Irae by Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny. The English translation is used verbatim in Dick's novel Ubik two years later.

Music

See also: Music for the Requiem MassMusical settings

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The words of "Dies irae" have often been set to music as part of the Requiem service. In some settings, it is broken up into several movements; in such cases, "Dies irae" refers only to the first of these movements, the others being titled according to their respective incipits.

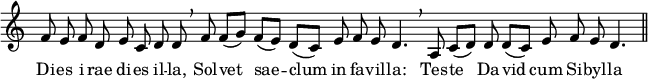

The original setting was a sombre plainchant (or Gregorian chant). It is in the Dorian mode. In four-line neumatic notation, it begins:

In 5-line staff notation:

The earliest surviving polyphonic setting of the Requiem by Johannes Ockeghem does not include "Dies irae". The first polyphonic settings to include the "Dies irae" are by Engarandus Juvenis (1490) and Antoine Brumel (1516) to be followed by many composers of the renaissance. Later, many notable choral and orchestral settings of the Requiem including the sequence were made by composers such as Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi, and Stravinsky.

Musical quotations

The traditional Gregorian melody has been used as a theme or musical quotation in many classical compositions, film scores, and popular works, including:

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier – Prose des morts – Dies irae H. 12 (1670)

- Joseph Haydn – Symphony No. 103, "The Drumroll" (1795)

- Hector Berlioz – Symphonie fantastique (1830), Requiem (1837)

- Charles-Valentin Alkan – Souvenirs: Trois morceaux dans le genre pathétique, Op. 15 (No. 3: Morte) (1837)

- Franz Liszt – Totentanz (1849)

- Charles Gounod – Faust opera, act 4 (1859)

- Modest Mussorgsky – Songs and Dances of Death, No. 3 "Trepak" (1875)

- Camille Saint-Saëns – Danse Macabre, Symphony No. 3 (Organ Symphony), Requiem (1878)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Manfred Symphony, Orchestral Suite No. 3 (1884)

- Gustav Mahler – Symphony No. 2, movements 1 and 5 (1888–94)

- Johannes Brahms – Six Pieces for Piano, Op. 118, No. 6, Intermezzo in E-flat minor (1893)

- Alexander Glazunov – From the Middle Ages Suite, No. 2 "Scherzo", Op. 79 (1902)

- Sergei Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 1, Op. 13 (1895); Symphony No. 2, Op. 27 (1906–07); Piano sonata No. 1 (1908); Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 (1908); The Bells choral symphony, Op. 35 (1913); Études-Tableaux, Op. 39 No. 2 (1916); Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 (1934); Symphony No. 3, Op. 44 (1935–36); Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1940)

- Hans Huber quotes the melody in the second movement ("Funeral March") of his Symphony No. 3 in C major, Op. 118 (Heroic, 1908).

- Alexander Kastalsky – Requiem for Fallen Brothers, movements 3 and 4 (1917)

- Gustav Holst – The Planets, movement 5, "Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age"

- Nikolai Myaskovsky – Symphony No. 6, Op. 23 (1921–23)

- Eugène Ysaÿe – Solo Violin Sonata in A minor, Op. 27, No. 2 "Obsession" (1923)

- Gottfried Huppertz – Score for Metropolis (1927)

- Ottorino Respighi – quoted near the end of the second movement of Impressioni Brasiliane (Brazilian Impressions) (1928)

- Arthur Honegger – La Danse des Morts, H. 131 (1938)

- Bernard Hermann quotes it in the main theme for Citizen Kane (1941)

- Ernest Bloch – Suite Symphonique (1944)

- Aram Khachaturian – Symphony No. 2 (1944)

- Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji – Sequentia cyclica super "Dies irae" ex Missa pro defunctis (1948–49) and nine other works

- Gerald Fried – Opening theme for The Return of Dracula, 1958

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco – 24 Caprichos de Goya, Op. 195: "XII. No hubo remedio" (plate 24) (1961), Candide, Illustrazione No. III Marcia degli inquisitori e il terremoto (Lisbona 1755) (1944)

- Eric Ball – "Resurgam" (1950)

- Dmitri Shostakovich – Symphony No. 14; Aphorisms, Op. 13 – No. 7, "Dance of Death" (1969)

- George Crumb – Black Angels (1970)

- György Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre (1974–77)

- Leonard Rosenman – the main theme of The Car (1977)

- Stephen Sondheim – Sweeney Todd – quoted in "The Ballad of Sweeney Todd" and the accompaniment to "Epiphany" (1979)

- Jethro Tull – The instrumental track "Elegy" featured on the band's 12th studio album Stormwatch is based on the melody.

- Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind – Opening theme for The Shining, 1980

- Jerry Goldsmith – scores for The Mephisto Waltz (1971) and Poltergeist (1982) – quoted during the track "Escape from Suburbia"

- Ennio Morricone – "Penance" from his score for The Mission (1986)

- John Williams – "Old Man Marley" leitmotif from his score for Home Alone (1990)

- Alan Menken, Stephen Schwartz – The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) soundtrack; "The Bells of Notre Dame" features passages from the first and second stanzas as lyrics.

- Michael Daugherty – Metropolis Symphony 5th movement, "Red Cape Tango"; Dead Elvis (1993) for bassoon and chamber ensemble

- Donald Grantham – Baron Cimetiére's Mambo (2004)

- Thomas Adès – Totentanz (2013)

- Jerad Tomasino – Music From The Hit Television Series… or A Celebration of Life, "Music From The Hit Television Series" (2016)

- Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez – Frozen II (soundtrack), "Into the Unknown" (2019)

References

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Dies Iræ" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Scritti vari di Filologia", The Catholic Encyclopædia, Rome: New Advent, 1901, p. 488

- Bugnini, Annibale (1990), "46.II.1", The Reform of the Liturgy: 1948–1975, The Liturgical Press, p. 773

- ^ Liturgia Horarum, vol. IV, Vaticana, 2000, p. 489

- Missale Romanum (PDF). Vatican City: Catholic Church. 1962. p. 706.

-

The full text of Dies Irae (Irons, 1912) at Wikisource

The full text of Dies Irae (Irons, 1912) at Wikisource

- The Hymnal, USA: The Episcopal Church, 1940

- The Order for Funerals for use by the Ordinariates erected under the auspices of the Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum cœtibus (PDF), United States: US Ordinariate

- McKenna, Malachy (ed.), The Spiritual Rose, Dublin: School of Celtic Studies – Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh, Institute for Advanced Studies – Institiúid Ard-Léinn Bhaile Átha Cliath, F 2.22, archived from the original on April 6, 2007

- Leroux, Gaston (1985). The Phantom of the Opera. Barnes & Noble. p. 139.

- Vorderman, Carol (2015). Help your Kids With Music (1st American ed.). London: Dorling-Kindersley. p. 143.

- Lintgen, Arthur, "Tchaikovsky: Manfred Symphony", Fanfare (review)

- Leonard, James. Tchaikovsky: Suite No. 3; Stravinsky: Divertimento at AllMusic. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Cummings, Robert. Intermezzo for piano in E-flat minor, Op. 118/6 at AllMusic. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- =Symphony No. 3, Op. 118 'Heroische' (Huber: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Naxos 5.574245

- Greenberg, Robert (2011), The 30 Greatest Orchestral Works, The Great Courses, The Teaching Company, ISBN 9781598037708

- "Sonata in A minor for Solo Violin ("Obsession"), Op. 27, No. 2 (Eugène Ysaÿe)". LA Phil. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- Johnson, Edward. Liner notes: Respighi – Church Windows / Brazilian Impressions, CHAN 8317. Chandos.

- Spratt, Geoffrey K. The Music of Arthur Honegger. Cork University Press, 1985.

- Death (2015-11-09). "Pop Culture Keeps Resurrecting This Deathly Gregorian Chant". The Federalist. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- Simmons, Walter (2004), Voices in the Wilderness: Six American Neo-romantic Composers, Scarecrow, ISBN 0-8108-4884-8

- "Ernest Bloch – Suite Symphonique". Boosey & Hawkes]]. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- Roberge, Marc-André, "Citations of the Dies irae", Sorabji Resource Site, Canada: U Laval

- "Tedesco: 24 Caprichos de Goya, Op. 195". naxos.com.

- Candide, Op. 123 (Castelnuovo-Tedesco): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Pontins Championship 2003 – Test Piece Reviews: Resurgam". www.4barsrest.com. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- Zadan, Craig (1989). Sondheim & Co (2nd ed.). Perennial Library. p. 248. ISBN 0-06-091400-9.

- Webb, Martin (2019). "And the Stormwatch Brews...". Stormwatch: The 40th Anniversary Force 10 Edition. Chrysalis Records.

- Gengaro, Christine Lee (2013). Listening to Stanley Kubrick: The Music in His Films. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-8108-8564-6.

- Larson, Randall D. (1983). "Jerry Goldsmith on Poltergeist and NIMH: A Conversation with Jerry Goldsmith by Randall D. Larson". The CinemaScore & Soundtrack Archives. CinemaScore. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Tagg, Philip, Musemes from Morricone's music for The Mission (PDF) (analysis)

- Hoyt, Alia, Why Sountracks love the Day of Wrath Theme (analysis)

- Chorus, David Ogden Stiers, Paul Kandel & Tony Jay – The Bells of Notre Dame, retrieved 2021-05-12

- About this Recording – 8.559635 – Daugherty, M.: Metropolis Symphony / Deus ex Machina (T. Wilson, Nashville Symphony, Guerrero), Naxos

- Daugherty, Michael, Dead Elvis, archived from the original on 2018-08-06, retrieved 2013-01-20

- Grantham, Donald (2004), "Donald Grantham", in Camphouse, Mark (ed.), Composers on Composing for Band, vol. 2, Chicago: GIA, pp. 100–101, ISBN 1-57999-385-0

- "Nov 3 2016 Thursday, 8:00 PM". Boston Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- Cohn, Gabe (29 November 2019). "How to Follow Up 'Frozen'? With Melancholy and a Power Ballad". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

External links

Works related to Dies Irae at Wikisource

Works related to Dies Irae at Wikisource Media related to Dies Irae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dies Irae at Wikimedia Commons- "Dies Iræ", Franciscan Archive. Includes two Latin versions and a literal English translation.

- Day of Wrath, O Day of Mourning (translation by William J. Irons)