This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dan Palraz (talk | contribs) at 10:17, 6 March 2022 (Reverting to previous lead). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:17, 6 March 2022 by Dan Palraz (talk | contribs) (Reverting to previous lead)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the Palestinian village. For other uses, see Sebastia (disambiguation). Municipality type B in Nablus, State of Palestine| Sebastia | |

|---|---|

| Municipality type B | |

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | سبسطية |

| • Latin | Sabastiya Sabastia Sebaste (unofficial) |

View of Sebastia, 2016 View of Sebastia, 2016 | |

| |

| Coordinates: 32°16′34″N 35°11′43″E / 32.27611°N 35.19528°E / 32.27611; 35.19528 | |

| Palestine grid | 168/186 |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Nablus |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality (from 1997) |

| • Head of Municipality | Ma’amun Harun Kayed |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,810 dunams (4.8 km or 1.9 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 4,114 |

| • Density | 860/km (2,200/sq mi) |

Sebastia (Template:Lang-ar, Sabastiyah; Template:Lang-el, Sevasti; Template:Lang-he, Sebastiya; Template:Lang-la) is a Palestinian village of over 4,500 inhabitants, located in the Nablus Governorate of the State of Palestine, some 12 kilometers northwest of the city of Nablus.

Sebastia is believed to be one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the West Bank.

A prominent village during the Hellenistic era and under the Roman Empire, Christians and Muslims believe Sebastia's Nabi Yahya Mosque to be the burial site of John the Baptist.

Situated on a hill with panoramic views across the West Bank, Sebastia also contains ruins that comprise remains from six successive cultures dating back more than 10 000 years: Canaanite, Israelite, Hellenistic, Herodian, Roman and Byzantine.

Etymology

In ancient times, Sebastia was known as Samaria (Template:Lang-he) which translates into "watch" or "watchman" in English. The city of Samaria later gave its name to the region of Samaria, the ancient Hebrew name used for the central region of the Land of Israel, surrounding the city of Shechem (modern-day Nablus).

According to first-century historian Josephus, Herod the Great renamed the city Sebastia in honor of the Roman emperor Augustus. The Greek sebastos, "venerable", is a translation of the Latin epithet augustus. The modern village name preserves the Roman-period name of Sebaste.

History and archaeology

Ancient Samaria

In the 9th and the 8th centuries BCE, Samaria was capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel. According to the Hebrew Bible, Omri, the sixth king of Israel (ruled 880s–870s BCE), purchased a hill owned by an individual (or clan) named Shemer for two talents of silver, and built its new capital on its broad summit, replacing the Israel's previous capital of Tirzah (1 Kings 16:24). Samaria is situated on an oblong hill, with steep but not inaccessible sides, and a long flat top. As such, it might had possessed many advantages for the Israelites. Omri resided here during the last six years of his reign (1 Kings 16:23).

It was the only great city of Israel created by the sovereign. All the others had been already consecrated by patriarchal tradition or previous possession. But Samaria was the choice of Omri alone. He, indeed, gave to the city which he had built the name of its former owner, but its especial connection with himself as its founder is proved by the designation which it seems Samaria bears in Assyrian inscriptions, "Beth-Khumri" ("the house or palace of Omri"). (Stanley)

According to some biblical scholars, the earliest reference to a settlement at this location may be the town of Shamir, which according to the Hebrew Bible was the home of the judge Tola in the 12th century BC (Judges 10:1–2).

Omri is thought to have granted the Arameans the right to "make streets in Samaria" as a sign of submission (1 Kings 20:34). This probably meant permission was granted to the Aramean merchants to carry on their trade in the city. This would imply the existence of a considerable Aramean population.

According to the biblical narrative, Samaria was frequently besieged. In the days of Ahab, Hadadezer of Aram-Damascus came up against it with thirty-two vassal kings, but was defeated with a great slaughter (1 Kings 20:1–21). A second time, the next year, he assailed it; but was again utterly routed, and was compelled to surrender to Ahab (1 Kings 20:28–34), whose army, as compared with that of Hadadezer, was no more than "two little flocks of kids" (1 Kings 20:27).

Biblical tradition holds that in the days of Jehoram, Ben Hadad again laid siege to Samaria. But just when success seemed to be within their reach, they suddenly broke off the siege, alarmed by a mysterious noise of chariots and horses and a great army, and fled, leaving their camp with all its contents behind them. The famished inhabitants of the city were soon relieved from the abundance of the spoil of the Syrian camp; and it came to pass, according to the word of Elisha, that "a measure of fine flour was sold for a shekel, and two measures of barley for a shekel, in the gates of Samaria" (2 Kings 7:1–20).

In 720 BCE, Samaria fell to the Neo-Assyrian Empire following a three-year siege, bringing an end to the Kingdom of Israel. Sargon II of Assyria recorded the city's fall: "Samaria I looked at, I captured; 27,280 men who dwelt in it I carried away". Some of the Israelite captives were resettled in the Khabur region, and the rest in the land of the Medes, thus establishing Hebrew communities in Ecbatana and Rages.

After the fall of the Kingdom of Israel, Samaria became an administrative center under Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian rule.

Many important archeological findings were discovered at Ancient Samaria. These include an royal Israelite palace dating from the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. 500 pieces of carved ivory were found in the Samaria, and were identified by some scholars with the "palace adorned with ivory" mentioned in the Bible (1 Kings 22:39). The Samaria Ostraca, a collection of 102 ostraca written in the Paleo-Hebrew Script were unearthed by George Andrew Reisner of the Harvard Semitic Museum.

Classical antiquity

Samaria was destroyed by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, and was destroyed again by Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in 108 BCE. Pompey rebuilt the town in the year 63 BCE.

In 27 BCE, Augustus appointed Herod the Great King of Judea; The city was rebuilt by the Herod the Great between the years 30–27 BCE. bringing in six-thousand new inhabitants, and named it "Sebastia", meaning "Augustus", in the Emperor's honor. Herod the Great had his sons Alexander and Aristobulus brought to Sebastia and strangled there in 7 BCE, after a trial in Berytus, with the approbation of Augustus.

Sherds from the Late Roman, Byzantine, early Muslim and Medieval eras have been found in modern-day Sebastia.

Medieval period

Sebastia was the seat of a bishop in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is mentioned in the writings of Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229), the Syrian geographer, who situates it as part of the military district of Filastin in the province of Syria, located two days from that city, in the Nablus District. He also writes, "There are here the tombs of Zakariyyah and Yahya, his son, and of many other prophets and holy men."

Ottoman era

Sebastia was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, and in 1596 it appeared in the tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Jabal Sami, part of Sanjak Nablus. It had a population of 20 households and 3 bachelors, all Muslim. The villagers paid taxes on wheat, barley, summer crops, olive trees, occasional revenues, goats and/or beehives; a total of 5,500 akçe.

The French explorer Victor Guérin visited the village in 1870 and found it to have less than a thousand inhabitants.

In 1882, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Sebastia as "A large and flourishing village, of stone and mud houses, on the hill of the ancient Samaria. The position is a very fine one; the hill rises some 400 to 500 feet above the open valley on the north, and is isolated on all sides but the east, where a narrow saddle exists some 200 feet lower than the top of the hill. There is a flat plateau on the top, on the east end of which the village stands, the plateau extending westwards for over half a mile. A higher knoll rises from the plateau, west of the village, from which a fine view is obtained as far as the Mediterranean Sea. The whole hill consists of soft soil, and is terraced to the very top. On the north it is bare and white, with steep slopes, and a few olives; a sort of recess exists on this side, which is all plough-land, in which stand the lower columns. On the south a beautiful olive-grove, rising in terrace above terrace, completely covers the sides of the hill, and a small extent of open terraced-land, for growing barley, exists towards the west and at the top. The village itself is ill-built, and modern, with ruins of a Crusading church of Neby Yahyah (St. John the Baptist), towards the northwest. A sarcophagus lies by the road on the north-east, but no rock-cut tombs have as yet been noticed on the hill, though possibly hidden beneath the present plough-land. There is a large cemetery of rock-cut tombs to the north, on the other side of the valley. The neighbourhood of Samaria is well supplied with water. In the months of July and August a stream was found (in 1872) in the valley south of the hill, coming from the spring (Ain Harun), which has a good supply of drinkable water, and a conduit leading from it to a small ruined mill. Vegetable gardens exist below the spring. To the east is a second spring called 'Ain Kefr Ruma, and the valley here also flows with water during part of the year, other springs existing further up it. The threshing-floors of the village are on the plateau north-west of the houses. The inhabitants are somewhat turbulent in character, and appear to be rich, possessing very good lands. There is a Greek Bishop, who is, however, non-resident; the majority of the inhabitants are Moslems, but some are Greek Christians."

Between 1915 and 1938, Sebastia was served by two stations on the Afula–Nablus–Tulkarm branch line of the Jezreel Valley railway: Mas'udiya station at the three-way junction, around 1.5 km to the west of the village, and Sabastiya station, around 1.5 km to the south.

The site was first excavated by the Harvard Expedition, initially directed by Gottlieb Schumacher in 1908 and then by George Andrew Reisner in 1909 and 1910; with the assistance of architect C.S. Fisher and D.G. Lyon.

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Sabastia had a population of 572; 10 Christians and 562 Muslim. This had increased in the 1931 census to 753; 2 Jews, 20 Christians and 731 Muslim, in a total of 191 houses.

In the 1945 statistics Sebastia had a population of 1,020; 980 Muslims and 40 Christians, with 5,066 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 1,284 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 3,493 used for cereals, while 90 dunams were built-up land.

The second expedition was known as the Joint Expedition, a consortium of 5 institutions directed by John Winter Crowfoot between 1931 and 1935; with the assistance of Kathleen Mary Kenyon, Eliezer Sukenik and G.M. Crowfoot. The leading institutions were the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Palestine Exploration Fund, and the Hebrew University. In the 1960s small scale excavations directed by Fawzi Zayadine were carried out on behalf of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

Jordanian era

In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Sebastia came under Jordanian rule.

In 1961, the population was 1,345.

Post-1967

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Sebastia has been held under Israeli military occupation, while the Palestinian Authority is the civil authority of the area.

In modern-day Sebastia, the village's main mosque, known as the Nabi Yahya Mosque, stands within the remains of a Crusader cathedral that is believed to be built upon the tombs of the prophets Elisha, Obediah and John the Baptist beside the public square. There are also Roman royal tombs, and a few medieval and many Ottoman era buildings which survive in a good state of preservation. Jordanian archaeologists had also restored the Roman theater near the town.

In late 1976, the Israeli settlers movement, Gush Emunim, attempted to establish a settlement at the Ottoman train station. The Israeli government did not approve and the group that was removed from the site would later found the settlement of Elon Moreh adjacent to Nablus.

Today, Sebastia is a Palestinian village of over 4,500 inhabitants, located in the Nablus Governorate of the Palestinian Authority. The ancient site of Sebastia is located just above the built-up area of the modern day village on the eastern slope of the hill.

Ecclesiastical see

The Archdiocese of Sebastia is part of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Starting with 2005, its archbishop has been Theodosios (Hanna).

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Short chronology timeline

- List of modern names for biblical place names

References

- Municipalities Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Nablus Municipality

- ^ 2007 PCBS Census. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. p.110.

- "Nablus". Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sebastia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- "Sebastia | Nablus, Palestinian Territories Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- "Sebastia | Nablus, Palestinian Territories Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- "Holy Land Blues". Al-Ahram Weekly. 11 January 2006. Archived from the original on March 11, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- For excavations conducted during the Ottoman period, see Reisner, G.A.; Fisher, C.S.; Lyon, D.G. (1924). Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1908–1910 (2 vols. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.. See also: The Augusteum at Samaria-Sebaste

- Tappy, Ron E. (1992-01-01). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria. Volume 1: Early Iron Age through the Ninth Century BCE. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004369665. ISBN 978-90-04-36966-5.

- "Samaria | historical region, Palestine | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- Josephus, Antiquities (Book xv, chapter 246).

- "Sebastian". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Pummer, Reinhard (2019), "Samaria", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–3, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah11208.pub2, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, S2CID 241784278, retrieved 2021-12-22

- Omri, king of the 10 tribes of Israel, built the city and settled his men in the Old City, in accordance with the account relayed in the Hebrew Bible (1 Kings 16:24). Compare Josephus, Antiquities (Book viii, chapter xii, verse 5)

- Boling, R.G. (1975). Judges: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. (Anchor Bible, Volume 6a), Page 185

- Pummer, Reinhard (2019), "Samaria", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–3, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah11208.pub2, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, S2CID 241784278, retrieved 2021-12-22

- Finkelstein, Israel (2011-11-01). "Observations on the Layout of Iron Age Samaria". Tel Aviv. 38 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1179/033443511x13099584885303. ISSN 0334-4355. S2CID 128814117.

- Tappy, Ron E. (1992-01-01). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria. Volume 1: Early Iron Age through the Ninth Century BCE. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004369665. ISBN 978-90-04-36966-5.

- Pienaar, D. N. (2008-12-01). "Symbolism in the Samaria ivories and architecture". Acta Theologica. 28 (2): 48–68. hdl:10520/EJC111399.

- Hebrew Ostraca from Samaria, David G. Lyon, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan., 1911), pp. 136–143, quote: "The script in which these ostraca are written is the Phoenician, which was widely current in antiquity. It is very different from the so-called square character, in which the existing Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible are written."

- Noegel, p.396

- ^ Sebaste, Holy Land Atlas Travel and Tourism Agency.

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) i.xx.§3

- Segal, Arthur (2017). "Samaria-Sebaste. Portrait of a polis in the Heart of Samaria". Études et Travaux (Institut des Cultures Méditerranéennes et Orientales de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences). XXX (30): 409. doi:10.12775/EtudTrav.30.019. ISSN 2084-6762.

- Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) i.xxi.§2

- Josephus Flavius Antiquities book 16 chapter 11 para 7

- ^ Zertal, 2004, pp. 463-464

- Dauphin, 1998, pp. 766–7

- Le Strange, 1890, p. 523.

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 129

- Guérin, 1875, pp. 188–96

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, pp. 160-161

- Reisner, G. A.; C.S. Fisher, and D.G. Lyon (1924). Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1908–1910. (Vol 1: Text , Vol 2: Plans and Plates ), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

- Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Nablus, p. 24

- Mills, 1932, p. 64

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 19

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 61

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 107

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 157

- Crowfoot, J. W.; G.M. Crowfoot (1938). Early Ivories from Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste. reports of the work of the Joint expedition in 1931–1933 and of the British expedition in 1935; no. 2). London: Palestine Exploration Fund, ISBN 0-9502279-0-0

- Crowfoot, J. W.; K.M. Kenyon and E.L. Sukenik (1942). The Buildings at Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste. Reports of the work of the joint expedition in 1931–1933 and of the British expedition in 1935; no.1). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Crowfoot, J. W.; K.M. Kenyon and G.M. Crowfoot (1957). The Objects from Samaria (Samaria; Sebaste, reports of the work of the joint expedition in 1931;1933, and of the British expedition in 1935; no.3). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Zayadine, F (1966). "Samaria-Sebaste: Clearance and Excavations (October 1965 – June 1967)". Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, vol. 12, pp. 77–80

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 26

- ^ Burgoyne, Michael Hamilton; Hawari, M. (May 19, 2005). "Bayt al-Hawwari, a hawsh House in Sabastiya". Levant. 37. Council for British Research in the Levant, London: 57–80. doi:10.1179/007589105790088913. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Pringle, 1998, pp. 283 -290

- United Nations Development Programme (23 April 2003). "Spain helps restore Sebastia, Palestinian town with historic sites". United Nations. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Netzer, E., The Augusteum at Samaria-Sebaste — A New Outlook (Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies), vol. 19 of the Michael Avi-Yonah Memorial Volume, Jerusalem 1987, pp. 97 - 105. See also article, Sebaste: Tribute to an Emperor.

- Nadav Shelef (2009). "Lords of the Land: The War over Israel's Settlements in the Occupied Territories, 1967–2007 (review)". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 27 (4): 138–140. doi:10.1353/sho.0.0411. ISSN 1534-5165. S2CID 144580732.

- "Sebastia | Nablus, Palestinian Territories Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- Burgoyne, Michael Hamilton; Hawari, M. (May 19, 2005). "Bayt al-Hawwari, a hawsh House in Sabastiya". Levant. 37. Council for British Research in the Levant, London: 57–80. doi:10.1179/007589105790088913. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Maria C. Khoury (2 January 2006). "A Rare Day for Orthodoxy in the Holy Land". Orthodox Christian News. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

Bibliography

- Anon (1908). "Excavations at Samaria". Harvard Theological Review. 1 (4). London: 518–519. doi:10.1017/s001781600000674x.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Reisner, G.A. (1910). "The Harvard Expedition to Samaria Excavations of 1909". Harvard Theological Review. 3 (2). London: 248–263. doi:10.1017/s0017816000006027.

- Zertal, A. (2004). The Manasseh Hill Country Survey. Vol. 1. Boston: BRILL. ISBN 9004137564.

Further reading

- Tappy, R. E. (1992). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria: Vol. I, Early Iron Age through the Ninth Century BCE. Harvard Semitic Studies 44. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press.

- Tappy, R. E. (2001). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria: Vol. II, The Eighth Century BCE. Harvard Semitic Studies 50. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

External links

- Welcome To Sabastiya

- Sebastiya, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 11: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Sabastiya, aerial photo, Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem ARIJ

- Development Priorities and Needs in Sabastiya, ARIJ

- Municipality of Sabastiya - Nablus Governorate - Palestine Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Throne villages, with Al Kayed Palace in Sabastiya, RIWAQ

- Samaria (city), biblewalks

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Samaria". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Samaria". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Vailhé, S. (1913). "Samaria". Catholic Encyclopedia.

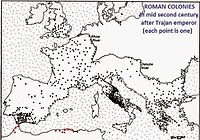

| Colonies of ancient Rome | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With correspondence to modern geography | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Europe |

|   | ||||||||||||||||||

| Levant |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||