This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Miss Mondegreen (talk | contribs) at 09:42, 16 February 2007 (→External links: remove spam). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:42, 16 February 2007 by Miss Mondegreen (talk | contribs) (→External links: remove spam)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For the musical collective, see Tanakh (band).Tanakh (Template:Lang-he) (also Tanach, IPA: [taˈnax] or , or Tenak, is an acronym that identifies the Hebrew Bible. The acronym is based on the initial Hebrew letters of each of the text's three parts:

- Torah Template:Hebrew meaning "Instruction". Also called the Humash Template:Hebrew meaning: "The five"; "The five books of Moses". Also called the "Pentateuch". The Torah is often referred to as the law of the Jewish people.

- Nevi'im Template:Hebrew meaning "Prophets". This term is associated with anything to do with the prophets.

- Ketuvim Template:Hebrew meaning "Writings" or "Hagiographa".

The writings are then separated into sections, for example; there are a group of history books namely, Ezra, Chronicles and Nehemiah. Others include the wisdom books these are: Job, Ecclesiastes and Proverbs. Poetry books; Psalms, Lamentation and Song of Solomon. Lastly there are other books, Ruth, Esther and the book of Daniel. The Tanakh is also called Template:Hebrew, Mikra or Miqra, meaning "that which is read".

Terminology

Mikra

The three-part division reflected in the acronym Tanakh is well attested to in documents from the Second Temple period and in Rabbinic literature. During that period, however, "Tanakh" was not used as a word or term; rather, the proper title was Mikra ("Reading"), because the biblical books were read publically. "Mikra" is thus analogous to the Latin term Scriptus, meaning "that which is written" (as in "Scripture" or "The Holy Scriptures").

Mikra continues to be used in Hebrew to this day alongside Tanakh to refer to the Hebrew scriptures. In modern spoken Hebrew, Mikra has a more formal flavor than Tanakh, where the former might refer to a university department, and the latter to a popular study group.

Hebrew Bible

Because the books included in the Tanakh were predominantly written in Hebrew, it may also be called the Hebrew Bible. Parts of Daniyel and Ezra, as well as a sentence in Yir'm'yahu (Jeremiah) and a two-word toponym in B'reshit (Genesis), are in Aramaic — but even these are written in the same Hebrew script.

Number of books

According to the Jewish tradition, the Tanakh consists of 24 books:

- 5 books of the Torah ("Instruction")

- 8 books of the Nviim ("Prophets")

- 11 books of the Ktuvim ("Writings" or "Scriptures")

Tanakh still developing during 1st century

In his book Against Apion, the 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus describes a still-formative phase of the Tanakh that only contains 22 sacred books (not 24), which "all Jews immediately - and from their very birth! - esteem to contain Divine doctrines, and persist in them, and, if occasion be, willingly die for them".

Per Josephus, the Jewish biblical canon only has 22 books in the 1st century:

- 5 books of the Torah: "five belong to Moses, which contain his laws and the traditions of the origin of humankind till his death".

- 13 books of the Nviim: "from the death of Moses till the reign of Artaxerxes king of Persia, who reigned after Xerxes, the Prophets who were after Moses wrote down what was done in their times in thirteen books".

- 4 books of the Ktuvim: "the remaining four books contain hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life".

Per Talmud, the Tanakh has eight books of the Nviim (Prophets). The extra five of the "thirteen" books that Josephus says "the Prophets wrote down", may include books such as the Book of Daniel, which is now found in the Tanakh among the Ktuvim. Thusly, nine out of the eleven books in the Ktuvim can be accounted for.

Perhaps, one of the two missing biblical books is the Book of Ester, which cannot be found among the many biblical texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Per Christian Traditions

These twenty-four books are the same books found in the Protestant Old Testament, but the order of the books is different. The enumeration differs as well: Christians count these books as thirty-nine, not twenty-four. This is because Jews often count as a single book what Christians count as several. However, the term Old Testament, while common, is often considered pejorative by Jews as it can be interpreted as being inferior or outdated relative to the New Testament, though traditional churches such as the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church insist on a continuity and coequal relationship between the Old and New Testaments.

As such, one may draw a technical distinction between the Jewish Tanakh and the similar, but not identical, corpus which Protestant Christians call the Old Testament. Thus, some scholars prefer Hebrew Bible as a term that covers the commonality of Tanakh and the Old Testament while avoiding sectarian bias.

The Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments contain six books not included in the Tanakh. They are called deuterocanonical books (literally "canonized secondly" meaning canonized later).

In Christian Bibles, Daniel and the Book of Esther sometimes include extra deuterocanonical material that is not included in either the Jewish or most Protestant canons.

Books of the Tanakh

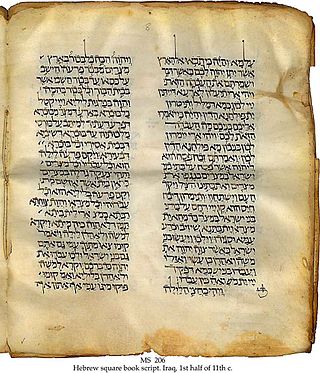

The Hebrew text originally consisted only of consonants, together with some inconsistently applied letters used as vowels (matres lectionis). During the early middle ages Masoretes codified the oral tradition for reading the Tanakh by adding two special kinds of symbols to the text: niqud (vowel points) and cantillation signs. The latter indicate syntax, stress (accentuation), and the melody for reading. According to tradition, this codification was made by Ezra, in the fourth century BCE.

The books of the Torah have generally-used names which are based on the first prominent word in each book. The English names are not translations of the Hebrew; they are based on the Greek names created for the Septuagint which in turn were based on Rabbinic names describing the thematic content of each of the Books.

The Torah ("Law") consists of:

- 1. Genesis ] / B'reshit]

- 2. Exodus ] / Sh'mot]

- 3. Leviticus ] / Vayiqra]

- 4. Numbers ] / B'midbar]

- 5. Deuteronomy ] / D'varim]

The books of Nevi'im ("Prophets") are:

- 6. Joshua ] / Y'hoshua]

- 7. Judges ] / Shophtim]

- 8. Samuel (I & II) ] / Sh'muel]

- 9. Kings (I & II) ] / M'lakhim]

- 10. Isaiah ] / Y'shayahu]

- 11. Jeremiah ] / Yir'mi'yahu]

- 12. Ezekiel ] / Y'khezqel]

- 13. The Twelve Minor Prophets ]]

The Kh'tuvim ("Writings") are:

- 14. Psalms ] / T'hilim]

- 15. Proverbs ] / Mishlei]

- 16. Job ] / Iyov]

- 17. Song of Songs ] / Shir Hashirim]

- 18. Ruth ] / Rut]

- 19. Lamentations ] / Eikhah]

- 20. Ecclesiastes ] / Qohelet]

- 21. Esther ] / Est(h)er]

- 22. Daniel ] / Dani'el]

- 23. Ezra-Nehemiah ] / Ezra wuNekhem'ya]

- 24. Chronicles (I & II) ] / Divrey Hayamim]

Chapters and verse numbers, book divisions

The chapter divisions and verse numbers have no significance in the Jewish tradition. Nevertheless, they are noted in all modern editions of the Tanakh so that verses may be located and cited. The division of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles into parts I and II is also indicated on each page of those books in order to prevent confusion about whether a chapter number is from part I or II, since the chapter numbering for these books follows their partition in the Christian textual tradition.

The adoption of the Christian chapter divisions by Jews began in the late middle ages in Spain, partially in the context of forced clerical debates which took place against a background of harsh persecution and of the Spanish Inquisition (the debates required a common system for citing biblical texts). From the standpoint of the Jewish textual tradition, the chapter divisions are not only a foreign feature with no basis in the mesorah, but also open to severe criticism of two kinds:

- The chapter divisions often reflect Christian exegesis of the Bible.

- Even when they do not imply Christian exegesis, the chapters often divide the biblical text at numerous points that may be deemed inappropriate for literary or other reasons.

Nevertheless, because they proved useful — and eventually indispensable — for citations, they continued to be included by Jews in most Hebrew editions of the biblical books. For more information on the origin of these divisions, see chapters and verses of the Bible.

The chapter and verse numbers were often indicated very prominently in older editions, to the extent that they overshadowed the traditional Jewish masoretic divisions. However, in many Jewish editions of the Tanakh published over the past forty years, there has been a major historical trend towards minimizing the impact and prominence of the chapter and verse numbers on the printed page. Most editions accomplish this by removing them from the text itself and relegating them to the margins of the page. The main text in these editions is unbroken and uninterrupted at the beginning of chapters (which are noted only in the margin). The lack of chapter breaks within the text in these editions also serves to reinforce the visual impact created by the spaces and "paragraph" breaks on the page, which indicate the traditional Jewish parashah divisions. Some versions have even introduced a new chapter system.

These modern Jewish editions present Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles (as well as Ezra) as single books in their title pages, and make no indication inside the main text of their division into two parts (though it is noted in the upper and side margins). The text of Samuel II, for instance, follows Samuel I on the very same page with no special break at all in the flow of the text, and may even continue on the very same line of text.

Oral Torah

- See: Oral law in Judaism.

Rabbinical Judaism believes that the Torah was transmitted side by side with an oral tradition. Other groups, such as Karaite Judaism and the majority of Christians, exceptions being certain Hebrew Roots and Messianic groups, do not accept this claim. Many terms and definitions used in the written law are undefined within the Torah itself, and the reader is assumed to be familiar with the context and details. This fact is presented as evidence to the antiquity of the oral tradition. An opposing argument is that only a small portion of the vast rabbinic works on the oral tradition can be described as mere clarifications and context. These rabbinic works, collectively known as "the oral law" Template:Hebrew, include the Mishnah, the Tosefta, the two Talmuds (Babylonian and Jerusalem), and the early Midrash compilations.

Available texts

- Tanakh, English translation, Jewish Publication Society, 1985, ISBN 0-8276-0252-9

- Jewish Study Bible, using NJPS (1985) translation, Oxford U Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-529754-7

- Tanach: The Stone Edition, Hebrew with English translation, Mesorah Publications, 1996, ISBN 0-89906-269-5

See also

- Jewish English Bible translations

- Bible

- Biblical canon

- Mikraot Gedolot

- Rabbinic literature

- Septuagint

- Samaritan Pentateuch

- Books of the Bible for a side-by-side comparison of Jewish, Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant canons.

- 613 mitzvot, the formal list of all 613 commandments that Jewish sages traditionally identify in the Torah

- Table of books of Judeo-Christian Scripture

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

External links

- Online Bible

- iTanakh.org An extensive list of links and resources pertaining to the study of the Tanakh

Online texts

- Download the complete Tanakh in Hebrew with translation and transliteration Lev Software

- Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible) at Wikisource in English (sample) and Hebrew (sample)

- TanakhML (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and King James Version)

- Unicode/XML Westminster Leningrad Codex - A transcription of the electronic source maintained by the Westminster Hebrew Institute. (Leningrad Codex)

- Holy Tanakh - English version of the Holy Tanakh

- Mechon Mamre - The Hebrew text of the Tanakh based on the Aleppo codex, edited according to the system of Rabbi Mordechai Breuer. Hebrew text comes in four convenient versions (including one with cantillation marks) and may be downloaded. The JPS 1917 English translation is included as well (including a parallel translation).

- Tanach on Demand - Custom PDF versions of any section of the Bible in Hebrew.

Reading guides

- A Guide to Reading Nevi'im and Ketuvim - Detailed Hebrew outlines of the biblical books based on the natural flow of the text (rather than the chapter divisions). The outlines include a daily study-cycle, and the explanatory material is in English.

- A detailed chart of the major figures and events in the Tanakh

- Judaica Press Translation (online translation of Tanakh and Rashi's entire commentary)