This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Goszei (talk | contribs) at 09:22, 19 February 2023 (additions). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:22, 19 February 2023 by Goszei (talk | contribs) (additions)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) American investigative journalist (born 1937)

| Seymour Hersh | |

|---|---|

Hersh in 2004 Hersh in 2004 | |

| Born | Seymour Myron Hersh (1937-04-08) April 8, 1937 (age 87) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Other names | Sy Hersh |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago (BA) |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, writer |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Sarah Klein

(m. 1964) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | George Polk Award (1969, 1973, 1974, 1981, 2004) Pulitzer Prize (1970) National Magazine Award (2004, 2005) George Orwell Award (2004) |

| Website | seymourhersh |

Seymour Myron "Sy" Hersh (born April 8, 1937) is an American investigative journalist and political writer. He gained recognition in 1969 for exposing the My Lai Massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam War, for which he received the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. During the 1970s, Hersh covered the Watergate scandal for The New York Times, also reporting on the secret U.S. bombing of Cambodia and the CIA's program of domestic spying. In 2004, he detailed the U.S. military's torture and abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq for The New Yorker. Hersh has won a record five George Polk Awards and two National Magazine Awards. He is the author of 11 books, including The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House (1983), an account of the career of Henry Kissinger which won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

In 2013, Hersh disputed the claim that Bashar al-Assad's government used chemical weapons on civilians at Ghouta during the Syrian Civil War, and in 2015, he reported that the U.S. had lied about the events around the killing of Osama bin Laden, both times attracting controversy and criticism from other reporters, such as Max Fisher for Vox and Eliot Higgins for The Guardian. In 2023, he wrote that the US in coordination with Norway had sabotaged the Nord Stream gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, again stirring controversy.Hersh has been criticized for his overreliance on unverifiable "anonymous" sources.

Early life and education

Seymour Myron Hersh was born in Chicago on April 8, 1937, to Isador and Dorothy Hersh (née Margolis), Yiddish-speaking Jews who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1920s from Lithuania and Poland, respectively. Isador's original surname was Hershowitz. As a teenager, Seymour helped run the family's dry cleaning shop on the city's South Side. He graduated from Hyde Park High School in 1954, then attended the University of Illinois Chicago and later the University of Chicago, where he graduated with a history degree in 1958. Hersh struggled to find a job, and worked briefly as a clerk at a Walgreens drug store before being admitted to the University of Chicago Law School in 1959; however, he was expelled after his first year due to poor grades.

Newspaper career

After returning for a brief time to Walgreens, Hersh began his career in journalism in 1959 with a seven-month stint at the City News Bureau of Chicago, first as a copyboy and later as a crime reporter. In 1960, he enlisted as an Army reservist, and spent six months at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. After returning to Chicago, in 1961 Hersh launched the Evergreen Dispatch, a weekly for the suburb of Evergreen Park. He moved to Pierre, South Dakota, in 1962 to work as a correspondent for United Press International (UPI). In 1963, Hersh moved back to Chicago to work for the Associated Press (AP), and in 1965 was transferred to Washington, D.C., to report on the Pentagon. While in Washington, he met and befriended the investigative journalist I. F. Stone, whose famed I. F. Stone's Weekly served as an inspiration. Hersh began to develop his journalistic methods, often walking out of regimented press briefings at the Pentagon to seek out one-on-one interviews with high-ranking officers in their lunch rooms. In 1967, he became part of the AP's first special investigative unit.

Hersh's first national break came that year from his reporting on the U.S. military's chemical and biological weapons programs. After the AP refused to run the articles he wrote on the subject, he quit to become a freelancer and sold his stories to The New Republic. His research became the basis for his first book, Chemical and Biological Warfare: America's Hidden Arsenal (1968). Later that year, Hersh's reporting was highlighted by the Dugway sheep incident, in which an aerial test of VX nerve agent at the U.S. Army's Dugway Proving Ground in Utah inadvertently killed more than 6,000 sheep belonging to local ranchers. These events contributed to the Nixon administration's subsequent decision to end the U.S. offensive biological weapons program in 1969.

In early 1968, Hersh served as the press secretary for anti–Vietnam War candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy in his unsuccessful campaign in the 1968 Democratic Party presidential primaries. After leaving the campaign after three months, Hersh returned to journalism as a freelancer covering Vietnam.

My Lai massacre

In 1969, Hersh's freelance reporting exposed the My Lai massacre, the killing of between 347 and 504 unarmed Vietnamese civilians (almost all women, children, and elderly men) by U.S. troops in a village on March 16, 1968.

On October 22, 1969, Hersh received a tip from Geoffrey Cowan, a lawyer and columnist for The Village Voice, about a soldier at Fort Benning in Georgia who was in the process of being court-martialled for allegedly killing 75 civilians in Vietnam. After speaking with a Pentagon contact and Fort Benning's public relations office, Hersh found an AP article published on September 7 that identified the soldier as Lieutenant William Calley. Hersh then located Calley's lawyer, George W. Latimer, who met with Hersh in Salt Lake City, Utah, and showed him a document that showed Calley was charged with the killing of 109 people. Hersh traveled to Fort Benning on November 11, where he gained the confidence of Calley's roommates and eventually Calley himself, whom he interviewed. Hersh's first article on My Lai, a cautious and conservative piece, was initially rejected by Life and Look magazines. Hersh next tried the anti-war Dispatch News Service run by David Obst, which on November 12 sold the story to 35 papers.

Follow-up articles in the papers revealed that the investigation was prompted by a letter from Ronald Ridenhour, a veteran who had collected information from interviews with soldiers who knew of the killings. In California, Hersh visited Ridenhour, who gave him their personal information; Hersh then traveled across the country to interview them, revealing three developments: that witnesses had been ordered to keep quiet, that the actual death count was in the hundreds, and that photos of the massacre existed. On November 20, Dispatch syndicated Hersh's second article, which was internationally circulated.

Hersh next interviewed Paul Meadlo, a soldier who admitted that he had killed dozens of civilians on the orders of Calley. Meadlo's mother told Hersh that she "sent them a good boy and they made him a murderer". Hersh's third article was syndicated by Dispatch on November 25, and that night an interview with Meadlo by Mike Wallace on the CBS News program 60 Minutes was broadcast on national television. The Army appointed General William R. Peers to head an official commission investigating the massacre. Hersh proceeded to visit 50 eyewitnesses over the next months, 35 of which agreed to talk. Gregory Olson told Hersh of random and vicious killings that he witnessed in the days before the massacre, and handed over a letter he wrote which told of an incident in which a civilian woman was kicked to death by soldiers. Hersh's fourth article was syndicated on December 2, and a fifth was syndicated days later. Ten pages of color photos of the massacre taken by army photographer Ronald L. Haeberle were printed in Life magazine on December 5.

Hersh won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. He later wrote to Robert Loomis, editor of Hersh's 1970 book on the massacre, My Lai 4:

Some will claim that I have attempted to exploit some dumb, out of service, overly talkative GIs. But few men are exposed to charges of murder... it is not a 'naming names and telling all affair.' In fact, one of the strengths is that discriminating readers will know how much more I know—and did not tell. I’m convinced that to give the name and hometown of a GI who committed rape and murder that day, or one who beheaded an infant, would not further the aim of the book. It is an exposé, but not of the men of Charlie Company. Something much more significant is being put to light... Both the killer and the killed are victims in Vietnam; the peasant who is shot down for no reason and the G.I. who is taught, or comes to believe, that a Vietnamese life somehow has less meaning than his wife's, or his sister's, or his mother's.

On March 14, 1970, the Peers Commission submitted to the Army a secret report that included 20,000 pages of testimony from over 400 witnesses. One of Hersh's sources leaked the testimony to him over the course of a year; it revealed that at least 347 civilians were killed, twice as many as the Army had conceded. The testimony formed the basis for two articles by Hersh in The New Yorker magazine, and his 1972 book on the investigation, Cover-Up.

The New York Times

In April 1972, Hersh was hired by The New York Times as an investigative journalist at the paper's Washington bureau. After the June 17 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington and the emergence of the Watergate scandal, the Times sought to catch up with the reporting of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein at The Washington Post, who broke several stories in 1972 linking the break-in to the Nixon campaign. Together with Walter Rugaber, Hersh produced extensive reporting for the Times on the scandal; an important article by him published on January 14, 1973, revealed the $400 monthly "hush money" payments being made to the burglars, shifting the press's focus from the events before the break-in to its cover-up. During 1973, he wrote more than 40 articles on the scandal, most appearing on page one. John Dean, the president's counsel, later stated that while it had been the Post's articles in 1972 that emboldened prosecutors, "the most devastating pieces that strike awfully close to home" were Hersh's in 1973 and 1974.

Hersh also contributed to the revelations around Operation Menu, the secret U.S. bombing of Cambodia. In 1972, he interviewed General John D. Lavelle, who had been relieved as commander of the Air Force in Southeast Asia. On June 11, an article by Hersh alleged that Lavelle was ousted because he had repeatedly ordered unauthorized bombings of North Vietnam. The ensuing "Lavelle affair" led to Senate Armed Services Committee hearings in September 1972. In early 1973, Major Hal Knight, who had supervised radar crews in Vietnam, wrote a letter to the Committee that confessed his key role in the cover-up of Operation Menu, in which he recorded fake bombing coordinates and burned his orders. Hersh learned of Knight after investigating another scandal in May 1973, in which Nixon and Kissinger had authorized wiretaps of aides at the National Security Council after the Cambodia operation was exposed in the Times in May 1969. After interviewing Knight, Hersh detailed the cover-up of Operation Menu in an article on July 15, 1973, one day before the start of Knight's public testimony before the committee. Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger admitted that day that the Air Force had flown 3,630 raids over Cambodia, dropping more than 100,000 tons of ordnance. Hersh continued to investigate who had ordered the cover-up: in a rare interview, Kissinger told Hersh that Nixon had "neither ordered nor was aware of any falsification". On July 31, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Earle Wheeler admitted that Nixon had ordered him to falsify records on the bombing; later that day, Nixon's impeachment on this basis was proposed by Representative Robert Drinan. During debate on Nixon's articles of impeachment in July 1974, his cover-up of the bombings was considered and rejected as an article.

In early 1974, Hersh planned to publish a story on "Project Jennifer" (later revealed to be codenamed Project Azorian), a covert CIA operation that partially recovered the sunken Soviet submarine K-129 from the floor of the Pacific Ocean with a purpose-built vessel, the Glomar Explorer. The ship, which was falsely presented as a underwater mineral mining vessel, was built by a company owned by billionaire Howard Hughes. After a discussion with CIA director William Colby, Hersh promised not to publish the story while the operation was still active, in order to avoid triggering a potential international incident. The Times eventually published Hersh's article on March 19, 1975, with an added five-paragraph explanation of the publishing history and one-year delay.

On September 8, 1974, Hersh reported that the CIA, with the approval of National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, spent $8 million to influence unions, political parties, and media in Chile in order to destabilize the government of socialist Salvador Allende, who was overthrown in the September 11, 1973, coup d'état that brought to power a dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet. Hersh followed up the story over the next two months, with 27 articles in total.

On December 22, 1974, Hersh exposed Operation CHAOS, a massive CIA program of domestic wiretapping and infiltration of anti-war groups during the Nixon administration, which was conducted in direct violation of the agency's charter. Hersh reported that at least 10,000 dossiers had been compiled on American citizens, including congressmen; the government eventually conceded the figure was closer to 300,000. He wrote 34 more articles on the story over the next months; it was a factor in the formation of the Rockefeller Commission and Church Committee, which investigated covert CIA operations. Hersh's exposure of Operation CHAOS was the first reporting to reveal contents of the so-called "Family Jewels" list of CIA reports on its illegal activities. According to Hersh, he felt "double-crossed" after learning of a January 1975 meeting between the paper's top editors (including executive editor A. M. Rosenthal) and President Gerald Ford, in which the president mentioned U.S. political assassinations–a comment which he subsequently asked to be struck from the record. The editors later agreed not to tell Hersh about the disclosure; Hersh thereafter decided to move away from reporting on the CIA.

On May 25, 1975, Hersh reported that the U.S. Navy was using submarines to collect intelligence inside the three-mile protected coastal zone of the Soviet Union, in a spy program codenamed "Holystone" which had persisted for at least 15 years. It was later revealed that Dick Cheney, one of Ford's top aides and later George W. Bush's vice president, proposed that the FBI search the home of Hersh and his sources in order to stop his reporting on the subject.

Hersh moved to New York later that year, and began reporting on corporate wrongdoing. In 1977, Hersh, assisted by Jeff Gerth, produced a three-part investigation into financial impropriety at Gulf and Western Industries, one of the country's largest conglomerates. The management at the Times was ambivalent about this new focus (with Hersh later stating that they " nearly as happy when we went after business wrongdoing as when we were kicking around some slob in government"), and he left the paper in 1979 to write a book about Kissinger, which he had been composing since 1973.

Investigative books: 1980s and 1990s

Hersh's 1983 book The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, which involved four years of exhaustive work and more than 1,000 interviews, became a best-seller and won him the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction and the Los Angeles Times book prize in biography. The 698-page volume contained 41 chapters, including 13 devoted to Kissinger's role in the Vietnam War and the secret bombing of Cambodia; other topics included his role in the Chilean coup, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, domestic wiretapping, and the White House Plumbers, as well as Hersh's criticism of his former Times colleagues (including Max Frankel and James Reston) for their proximity to Kissinger. One much-discussed revelation was the allegation that Kissinger, as an advisor to Nelson Rockefeller in the 1968 Republican Party presidential primaries, after his defeat to Nixon offered Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey damaging material on Nixon from the Rockefeller archives, before going to the Nixon campaign with secret information he had gathered from the Vietnam War's Paris peace negotiations. The book also alleges that Kissinger alerted Nixon to President Johnson's October 1968 halt in bombing 12 hours in advance, which earned him a place in the administration. The book's prose is noted for its density of information and its prosecutorial tone.

While writing the book, Hersh revisited his previous reporting on Edward M. Korry, the U.S. ambassador to Chile from 1967 to 1971. In 1974, Hersh had reported in the Times that Korry had known of the CIA's efforts to foment a coup. Korry, who had reacted to the claim with furious denial, demanded a front-page retraction in exchange for documents Hersh wanted for his book. The retraction, which Time called the "longest correction ever published", appeared on February 9, 1981. Peter Kornbluh, Chile expert at the National Security Archive, later judged based on declassified documents that Korry was unaware of CIA involvement. Also in the book was the claim that former Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai had been paid $20,000 per year by the CIA during the Johnson and Nixon administrations. Desai called the allegation "a scandalous and malicious lie", and filed a $50 million libel suit against Hersh. By the time the case went to trial in 1989, Desai, by then 93, was too ill to attend. Former CIA director Richard Helms and Kissinger testified under oath that at no time did Desai act in any capacity for the CIA, paid or otherwise. A Chicago jury ruled in favor of Hersh, saying Desai did not provide sufficient evidence that Hersh had published the information with the intent to do harm or with reckless disregard for the truth, either of which must be proven in a libel suit.

After the Kissinger book, Hersh worked on the 1985 PBS Frontline documentary Buying the Bomb, which reported on a Pakistani businessman who had attempted to smuggle electrical devices that could be used as nuclear bomb triggers out of the U.S. On June 12, 1986, an article by Hersh in the Times revealed that U.S.-backed Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was a key figure in weapons and narcotics trafficking. The reporting played a key role in starting a "political landslide" of revelations about Noriega; in 1989, the U.S. invaded Panama and captured him, bringing him to the U.S. to stand trial.

Hersh spent much of the 1980s writing two critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful books. In his 1986 title The Target Is Destroyed, Hersh examined the 1983 shootdown of Korean Air Lines Flight 007 by the Soviet Union. He concluded that the flight had strayed into prohibited airspace due to navigational errors; that the U.S. Air Force knew almost immediately that the Soviet military believed that it had attacked a military intruder; and that U.S. leaders, most notably Secretary of State George Shultz, misrepresented the situation to portray the Soviets as deliberate murderers of civilians. In The Samson Option (1991), Hersh chronicled the history of Israel's nuclear weapon program. He argued that a nuclear capability was sought from the founding of the state, and was achieved under a U.S. policy of feigned ignorance and indirect assistance. Hersh wrote that Israel received accelerated aid from the U.S. during the 1973 Yom Kippur War though "nuclear blackmail" (Israel's threat to use the weapons against its Arab enemies). Another major allegation was that intelligence passed to Israel by convicted spy Jonathan Pollard was given to the Soviet Union by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Another was that British media magnate Robert Maxwell had links to Mossad; Maxwell mysteriously died in a drowning accident two weeks after the book was published.

Hersh's 1997 book The Dark Side of Camelot, about the political career of John F. Kennedy, was controversial and heavily criticized. Shortly before its publication, it emerged in the press that Hersh had removed claims at the last minute which were based on forged documents provided to him by fraudster Lex Cusack, including a fake hush money contract between Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. An article about the controversy in The Washington Post said: "The strange and twisted saga of the JFK file is part cautionary tale, part slapstick farce, a story of deception and self-delusion in the service of commerce and journalism" (Hersh and a one-time co-author had received a $800,000 advance for the project). Other aspects of the book also came under criticism, including its prying into Kennedy's alleged sexual escapades based on interviews with his Secret Service guards, and its claim that Kennedy used Judith Exner as a courier to deliver cash to mobster Sam Giancana, made by a source who later recanted it before the Assassination Records Review Board.

In 1998, Hersh published Against All Enemies: Gulf War Syndrome: The War Between America's Ailing Veterans and Their Government, about Gulf War syndrome. He estimated that 15 percent of returning American troops were afflicted with the chronic and multi-symptomatic disorder, and challenged the government claim that they were suffering from war fatigue, as opposed to the effects of a chemical or biological weapon. He suggested the smoke from the destruction of a weapon depot that stored nerve gas at Khamisiyah in Iraq, which more than 100,000 soldiers were exposed to, as a possible cause.

Later investigations

Starting in 1993, Hersh was a regular contributor to The New Yorker. An article he wrote that year, based on his interviews with former CIA deputy director Richard J. Kerr, revealed how Pakistan acquired nuclear weapons with the consent of the Reagan and Bush administrations, and using material purchased within the U.S. In 2000, Hersh produced a 25,000-word article which detailed a massacre of Iraqi troops by soldiers under General Barry McCaffrey in the last days of the 1990–1991 Gulf War, at the Battle of Rumaila. Hersh performed six months of research for the story, and interviewed 300 people, including soldiers who had witnessed the killings. In July 2001, the magazine published Hersh's investigation of Mobil Oil's activities in Kazakhstan in the 1990s.

Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Hersh turned his focus to U.S. policy in the Middle East and the Bush administration's "war on terror". In The New Yorker, he reported on intelligence failures surrounding 9/11 (calling the U.S. agencies "confused, divided, and unsure about how the terrorists operated"); on the corruption of the Saudi royal family and its support for Osama bin Laden; on the instability of the Pakistani nuclear arsenal; and on U.S. military operations in Afghanistan (including a January 2002 story alleging that U.S. troops had inadvertently airlifted top al-Qaeda leaders to Pakistan).

Iraq and Abu Ghraib

In the lead-up to the launching of the Iraq War in 2003, Hersh argued against the claim that Saddam Hussein's alleged stockpile of weapons of mass destruction justified an invasion, and presented evidence that top Bush administration officials were avoiding facts that did not fit their belief that Saddam was connected to terrorism.

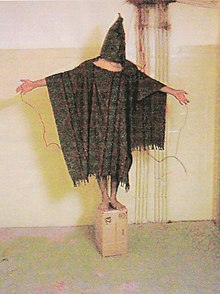

On April 30, 2004, Hersh published the first of three articles in The New Yorker which detailed the U.S. military's torture and abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib prison near Baghdad. The story, titled "Torture at Abu Ghraib", was accompanied by a now-infamous photo of an Iraqi prisoner standing on a box and wearing a black pointed hood, his hands spread out and attached to electrodes. A short piece with the photo and others had appeared two days earlier in the CBS News magazine 60 Minutes II. Hersh described the photos, which he had also obtained, but which his editor David Remnick had refused to publish for fear of sensationalizing an already sensational story:

In one, Private England, a cigarette dangling from her mouth, is giving a jaunty thumbs-up sign and pointing at the genitals of a young Iraqi, who is naked except for a sandbag over his head, as he masturbates. Three other hooded and naked Iraqi prisoners are shown, hands reflexively crossed over their genitals... In another, England stands arm in arm with Specialist Graner; both are grinning and giving the thumbs-up behind a cluster of perhaps seven naked Iraqis, knees bent, piled clumsily on top of each other in a pyramid... Yet another photograph shows a kneeling, naked, unhooded male prisoner... posed to make it appear that he is performing oral sex on another male prisoner, who is naked and hooded.

Hersh had obtained a secret 53-page report from an Army investigation by Major Antonio Taguba, which had been submitted on March 3. It detailed many abuses: pouring phosphoric liquid on naked detainees, beatings with a chair, threatening males with rape, sodomizing a detainee with a broom stick, and using military dogs to intimidate. Hersh also alleged that CIA officers and "interrogation specialists" from private military contractors had contributed to the mistreatment. In his second and third articles, "The Gray Zone" and "Chain of Command", Hersh alleged that the abuses stemmed from a secret Pentagon program known as "Copper Green", which encouraged physical abuse and sexual humiliation of military prisoners in an effort to generate intelligence. He revealed that the program was expanded from Afghanistan to Iraq in 2003 with the approval of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, both as an attempt to deal with a growing insurgency and as part of Rumsfeld's desire to "wrest control of America's clandestine and paramilitary operations from the CIA".

Scott Ritter, a former arms inspector, stated in an October 19, 2005 interview with Hersh that the US policy to remove Iraqi president Saddam Hussein from power started with US president George H. W. Bush in August 1990. Ritter stated that, while disarmament was used as the justification for the imposition of sanctions on Iraq, the real reason was the removal of Saddam Hussein from power. The CIA believed that containing Hussein through sanctions for six months would result in the collapse of his government. According to Hersh, this policy resulted in the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Iran

In the April 17, 2006 issue of The New Yorker, Hersh wrote that the Bush administration had plans for an air strike on Iran. Of particular note in his article was that a US nuclear first strike (possibly using the B61-11 bunker-buster nuclear weapon) was being considered to eliminate underground Iranian uranium enrichment facilities. In response, President Bush cited Hersh's reportage as "wild speculation".

When, in October 2007, he was asked in a Democracy Now! interview about presidential candidate Hillary Clinton's hawkish views on Iran, Hersh stated that Jewish donations were the main reason for these:

Money. A lot of the Jewish money from New York. Come on, let's not kid about it. A significant percentage of Jewish money, and many leading American Jews support the Israeli position that Iran is an existential threat. And I think it's as simple as that. When you're from New York and from New York City, you take the view of – right now, when you're running a campaign, you follow that line. And there's no other explanation for it, because she's smart enough to know the downside.

During one journalism conference, Hersh claimed that after the Strait of Hormuz incident, members of the Bush administration met in Vice President Dick Cheney's office to consider methods of initiating a war with Iran. One idea considered was staging a false flag operation involving the use of Navy SEALs dressed as Iranian PT boaters who would engage in a firefight with US ships. According to Hersh, this proposed provocation was rejected.

Killing of Osama bin Laden

See also: Death of Osama bin Laden § Alternative accountsIn September 2013, during an interview with The Guardian, Hersh commented that the 2011 raid that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden was "one big lie, not one word of it is true". He said that the Obama administration lied systematically and that American media outlets were reluctant to challenge the administration, saying, "It's pathetic, they are more than obsequious, they are afraid to pick on this guy ". Hersh later clarified that he didn't dispute Bin Laden's death in Pakistan, and rather meant that the lying began in the aftermath of bin Laden's death.

On May 10, 2015, Hersh published the 10,000-word article "The Killing of Osama bin Laden" in the London Review of Books (LRB) on the fourth anniversary of the Abbottabad raid that killed bin Laden (Operation Neptune Spear). It immediately went viral, crashing the LRB website.

Hersh's story was criticised by reporters, media commentators, academics and U.S. government officials. Politico's Jack Shafer described the story as "a messy omelet of a piece that offers little of substance for readers or journalists who may want to verify its many claims". Peter Bergen disputed Hersh's contentions, saying they "defy common sense"; Hersh responded that Bergen simply "views himself as the trustee of all things Bin Laden". A similar dismissal of Hersh's account came from former CIA Deputy Director Michael Morell. A former intelligence official who had direct knowledge of the operation speculated that the Pakistanis, who were furious that the operation took place without being detected by them, were behind the story as a way to save face.

In an article for the Columbia Journalism Review, the executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, Trevor Timm, wrote that "barely any follow-up reporting has been done to corroborate or refute his claims", and that Slate, for example, "ran five hit jobs on Hersh within 36 hours".

On May 12, the Pakistan-based journalist Amir Mir wrote that the "walk-in" who had provided the CIA with the information about bin Laden's whereabouts was Brigadier Usman Khalid of ISI.

Syrian War

On December 8, 2013, the London Review of Books published "Whose Sarin?", an article rejected by the New Yorker and Washington Post. Hersh wrote that the Obama administration had used "cherry picked intelligence" to try to justify a military strike against Syria after the Ghouta chemical attack and had ignored evidence the Syrian rebels could also have obtained Sarin gas. The White House denied the allegations made in the article, and a number of Syria and chemical weapons experts were critical of the article. Hersh's article had cited documents produced by US military intelligence which stated that it believed anti-government forces in Syria had the precursor chemicals for the production of Sarin.

On June 25, 2017, Welt am Sonntag published Hersh's article "Trump's Red Line". This had been rejected by the London Review of Books. He said there was a split between the U.S. intelligence community and president Donald Trump over the alleged 'sarin attack' at the rebel-held town of Khan Shaykhun in Idlib on April 4, 2017: "Trump issued the order despite having been warned by the U.S. intelligence community that it had found no evidence that the Syrians had used a chemical weapon". Bellingcat accused Hersh of sloppy journalism: "Hersh based his case on a tiny number of anonymous sources, presented no other evidence to support his case, and ignored or dismissed evidence that countered the alternative narrative he was trying to build." Journalist George Monbiot criticized Hersh for not giving the building coordinates to enable verification from satellite imagery and for relying on refuted analysis by Ted Postol.

Nord Stream sabotage

In February 2023, in a post on Substack, Hersh claimed that the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines had been carried out by the US Navy, the CIA, and the Norwegian Navy, under the direct order of President Biden. Hersh's report relied on an anonymous source who stated that, in June 2022, US Navy divers placed explosive C4 charges on the pipelines at strategic locations selected by the Norwegians. The source said that charges were placed under the cover of a multi-nation wargame simulation known as BALTOPS 22, and remotely detonated three months later by a signal from a sonar buoy dropped by a Norwegian P-8 surveillance plane.

Russia's foreign ministry spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, said the United States had questions to answer over its role in the explosions. A spokesperson for the United States National Security Council said the report was "utterly false and complete fiction". The CIA said the claims were "completely false", and this was also the reaction from the Norwegian Foreign Department.

Hersh wrote that NATO General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg had been cooperating with US intelligence services since the Vietnam war and has been cleared ever since. At the time the Vietnam war ended, Stoltenberg was 16 years old, and he had participated during the peak of the Anti-Vietnam war demonstrations in Norway. In 1985, Stoltenberg was part of the Workers' Youth League in Norway, when the Labour Party was working to withdraw Norway from NATO.

Hersh's article said the U.S. divers who planted the explosives had operated from a Norwegian Alta-class minesweeper. The Norwegian Defence Forces said no Norwegian Alta-class mine sweepers had participated in BALTOPS 22 or were in the vicinity of the explosions during the exercise.

Following Hersh's report, Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) tweeted that if the story was true, he and many of his fellow senators were not informed of the attack on Nord Stream. "If this turns out to be true, we've got a huge problem," Lee tweeted on February 8. The Chair of Russia's lower house of parliament called for an international investigation for "bringing Biden and his accomplices to justice". In the German Bundestag, members of parliament from the government disputed Hersh's credibility and urged that public discussion of the topic be minimized for security reasons; opposition members of parliament from AfD and Die Linke initiated a parliamentary debate on February 10 about Hersh's allegations, with Die Linke MP Sevim Dağdelen arguing that the government seemed uninterested in clarifying the truth about the bombings.

Hersh's reporting was criticized by other journalists. Eliot Higgins, the founder of investigative journalism group Bellingcat, said that Hersh was unable to get his article published in a reputed newspaper and that his reporting would only impress the likes of people who support Putin and al-Assad. Bellingcat journalist Christo Grozev described Hersh's report as "total fiction" and stated that his reporting is seriously damaging to journalism. Bellingcat made the false claim that Hersh's first interview was with Russian media. Simon Pirani questioned the veracity of the report. Kelly Vlahos, editorial director at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, characterized the public response to Hersh's article in the West as a "media blackout," arguing that criticisms of Hersh's reporting "do not explain the lack of mainstream coverage" of his allegations. In Russia, Hersh's publication was picked up by RT and the news agency TASS. In the USA, Jacobin & Democracy Now published interviews of Hersh, where he defended his reporting. In an interview with Radio War Nerd's Mark Ames & John Dolan (Writer), Hersh responded with derision regarding the journalistic credentials of the staff at Bellingcat, mentioning a "certain country's intelligence agency".

Other statements

Fatah al-Islam

In March 2007, Hersh asserted in a New Yorker piece that the United States and Saudi governments were funding the terrorist organization Fatah al-Islam through aid to Lebanese Sunni Prime Minister Fouad Siniora. Following the publication of the story, journalist Emmanuel Sivan in Beirut wrote that Hersh put forth the allegation without any reliable sources.

Seth Rich

In a January 2017 recorded telephone conversation about the 2016 death of former Democratic National Committee staffer Seth Rich, Hersh told former financial adviser Ed Butowsky that he had spoken to a Federal Bureau of Investigation source who confirmed the existence of information on Rich's laptop computer showing he had been in contact with WikiLeaks prior to his death. Although cautioned by Hersh that the information may not be true, Butowsky forwarded the secretly taped discussion to the Rich family setting off a flurry of activity in the media. Hersh later said that he had heard "gossip", and that he was fishing for information.

Richard Nixon

In his 2018 autobiography Reporter Hersh wrote that Richard Nixon had physically abused Pat Nixon but that he had chosen not to report about it because he considered it part of Nixon's private life. Hersh notes this as a decision he regretted.

September 11 attacks

In 2018, Hersh told an interviewer, "I don't necessarily buy the story that Bin Laden was responsible for 9/11. We really don't have an ending to the story. I’ve known people in the community. We don't know anything empirical about who did what."

Skripal poisoning

In August 2018, Hersh said about the Skripal poisoning that "the story of novichok poisoning has not held up very well. He was most likely talking to British intelligence services about Russian organised crime," and that the contamination of other victims was suggestive that the poisoning was the responsibility of organized crime, rather than being state-sponsored.

Use of anonymous sources

There has been sustained criticism of Hersh's use of anonymous sources. Critics, including Edward Jay Epstein and Amir Taheri, say he is over-reliant on them. Taheri, for example, when reviewing Hersh's Chain of Command (2004), complained:

As soon as he has made an assertion he cites a 'source' to back it. In every case this is either an un-named former official or an unidentified secret document passed to Hersh in unknown circumstances. ... By my count Hersh has anonymous 'sources' inside 30 foreign governments and virtually every department of the U.S. government.

In response to an article in The New Yorker in which Hersh alleged that the U.S. government was planning a strike on Iran, U.S. Defense Department spokesman Bryan G. Whitman said, "This reporter has a solid and well-earned reputation for making dramatic assertions based on thinly sourced, unverifiable anonymous sources."

In his Bin Laden story, "Hersh relied at least 55 times on an anonymous retired senior intelligence official." In 2015, Vox's Max Fisher wrote that "Hersh has appeared increasingly to have gone off the rails. His stories, often alleging vast and shadowy conspiracies, have made startling — and often internally inconsistent — accusations, based on little or no proof beyond a handful of anonymous 'officials'." Slate magazine's James Kirchick wrote, "Readers are expected to believe that the story of the Bin Laden assassination is a giant ‘fairy tale’ on the word of a single, unnamed source... Hersh's problem is that he evinces no skepticism whatsoever toward what his crank sources tell him, which is ironic considering how cynical he is regarding the pronouncements of the U.S. national security bureaucracy." Politico wrote in 2015 that Hersh's reporting had increasingly been called into question due to "his almost exclusive reliance on anonymous sources".

In a 2003 interview with the Columbia Journalism Review, David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, stated that he was aware of the identity of all of the unnamed sources used in Hersh's New Yorker articles, saying "I know every single source that is in his pieces...Every 'retired intelligence officer,' every general with reason to know, and all those phrases that one has to use, alas, by necessity, I say, 'Who is it? What's his interest?' We talk it through."

Speeches

In an interview with New York magazine, Hersh made a distinction between the standards of strict factual accuracy for his print reporting and the leeway he allows himself in speeches, in which he may talk informally about stories still being worked on or blur information to protect his sources. "Sometimes I change events, dates, and places in a certain way to protect people. ... I can't fudge what I write. But I can certainly fudge what I say."

Some of Hersh's speeches concerning the Iraq War have described violent incidents involving U.S. troops in Iraq. In July 2004, during the height of the Abu Ghraib scandal, he alleged that American troops sexually assaulted young boys:

Basically what happened is that those women who were arrested with young boys, children, in cases that have been recorded, the boys were sodomized, with the cameras rolling, and the worst above all of them is the soundtrack of the boys shrieking. That your government has. They're in total terror it's going to come out.

In a subsequent interview with New York magazine, Hersh regretted that "I actually didn't quite say what I wanted to say correctly. ... It wasn't that inaccurate, but it was misstated. The next thing I know, it was all over the blogs. And I just realized then, the power of—and so you have to try and be more careful." In Chain of Command, he wrote that one of the witness statements he had read described the rape of a boy by a foreign contract interpreter at Abu Ghraib, during which a woman took pictures.

Personal life

Hersh married Elizabeth Sarah Klein, a psychiatrist, in 1964. They have three children.

Awards, honors and associations

His journalism and publishing awards include the 1970 Pulitzer Prize, the 2004 National Council of Teachers of English George Orwell Award for Distinguished Contribution to Honesty and Clarity in Public Language, two National Magazine Awards, five George Polk Awards – making him that award's most honored laureate – and more than a dozen other prizes for investigative reporting:

- 1969: George Polk Special Award (for his My Lai reporting)

- 1970: Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting

- 1973: George Polk Award for Investigative Reporting; Scripps-Howard Public Service Award

- 1974: George Polk Award for National Reporting

- 1975: Sidney Hilman Award

- 1981: George Polk Award for National Reporting

- 1983: National Book Critics Circle Award and Los Angeles Times Book Prize for The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House

- 2003: National Magazine Award for Public Interest for his articles "Lunch with the Chairman", "Selective Intelligence", and "The Stovepipe"

- 2004: Following Hersh's 2004 articles in the New Yorker magazine exposing the Abu Ghraib scandal: National Magazine Award for Public Interest, Overseas Press Club Award, National Press Foundation's Kiplinger Distinguished Contributions to Journalism Award, and his fifth George Polk Award

- 2005: Ridenhour prize in the category Ridenhour courage prize

- 2005: American Library Association, Notable Book Council Award for Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib. HarperCollins.

- 2017: Sam Adams Award for Integrity

Publications

Books

- Chemical and Biological Warfare: America's Hidden Arsenal. New York: Bobbs-Merrill; London: MacGibbon & Kee. 1968. ISBN 0-586-03295-9.

- My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath. Random House. 1970. ISBN 0-394-43737-3.

- Cover-Up: The Army's Secret Investigation of the Massacre at My Lai 4. Random House. 1972. ISBN 0-394-47460-0.

- The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. Simon & Schuster. 1983. ISBN 0-671-44760-2.

- The Target Is Destroyed: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It. Random House. 1986. ISBN 0-394-54261-4.

- The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Random House. 1991. ISBN 0-394-57006-5.

- The Dark Side of Camelot. Little, Brown & Company. 1997. ISBN 0-316-36067-8.

- Against All Enemies: Gulf War Syndrome: The War Between America's Ailing Veterans and Their Government. New York: Ballantine Books. 1998. ISBN 0-345-42748-3.

- Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib. HarperCollins. 2004. ISBN 0-060-19591-6.

- The Killing of Osama Bin Laden. Verso. 2016. ISBN 978-1-784-78436-2.

- Reporter: A Memoir (Autobiography). New York, NY: Alfred Knopf, 2018 ISBN 978-0307263957

Book contributions

- "Foreword". Iraq Confidential: The Untold Story of the Intelligence Conspiracy to Undermine the UN and Overthrow Saddam Hussein by Scott Ritter. Nation Books, 2005. ISBN 1-56025-852-7. Hardcover.

Articles and reportage

- Full list of published articles in The New Yorker

- Collected articles for the London Review of Books

- St. Louis Post Dispatch: The My Lai Massacre stories

Notes

References

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (2018). Reporter: A Memoir. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780525521587.

- "Past Winners". The George Polk Awards. Long Island University. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- "1970 Pulitzer Prizes". The Pulitzer Prizes – Columbia University.

- "Past Recipients of the NCTE Orwell Award (pdf)" (PDF). National Council of Teachers of English. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- Fisher, Max (December 21, 2015). "Seymour Hersh's bizarre new conspiracy theory about the US and Syria, explained". Vox. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "It's clear that Turkey was not involved in the chemical attack on Syria". The Guardian. April 22, 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Miraldi, Robert (2013). Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1.

- ^ Sherman, Scott (July–August 2003). "The avenger: Sy Hersh, then and now". Columbia Journalism Review. 42 (2): 34. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008.

- ^ Jackson, David (June 25, 2004). "The muckraker". Chicago Tribune.

- Schwarz, Jon (June 2, 2018). "Seymour Hersh's New Memoir Is a Fascinating, Flabbergasting Masterpiece". The Intercept.

- Hersh, Seymour (June 2018). "Looking for Calley". Harpers.

- Manjoo, Farhad (December 22, 2005). "Prying open the Times". Salon. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- David Margolick. "U.S. Journalist Cleared of Libel Charge by Indian", The New York Times, October 7, 1989.

- "Court upholds ruling in Hersh libel suit". Chicago Tribune. January 31, 1992.

- Smith, Gaddis (Winter 1986–1987). "The Target Is Destroyed: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It". Foreign Affairs.

- Smith, Gaddis (Spring 1992). "The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal And American Foreign Policy". Foreign Affairs.

- "Scott Ritter and Seymour Hersh: Iraq Confidential". The Nation. October 26, 2005.

- Hersh, Seymour (April 17, 2006). "The Iran Plans". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- Stout, David (April 10, 2006). "Bush Calls Reports of Plan to Strike Iran 'Speculation'". The New York Times.

- "Seymour Hersh: White House Intensifying Plans to Attack Iran". Democracy Now. October 2, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- Shakir, Faiz (July 31, 2008). "To Provoke War, Cheney Considered Proposal To Dress Up Navy Seals As Iranians And Shoot At Them". Think Progress. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- O'Carroll, Lisa (September 27, 2013). "Seymour Hersh on Obama, NSA and the 'pathetic' American media". The Guardian. London. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- Mirkinson, Jack (October 7, 2013). "Guardian Amends Seymour Hersh Story With Correction About His Bin Laden Comments". The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- Kugelman, Michael (May 11, 2015). "3 Reasons to Be Skeptical of Seymour Hersh's Account of the Bin Laden Raid". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- Grynbaum, Michael M. (June 3, 2018). "I, Sy: Seymour Hersh's Memoir of a Life Making the Mighty Sweat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Zurcher, Anthony (May 11, 2015). "Questions swirl around Bin Laden report". Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "What's Wrong with Seymour Hersh's Conspiracy Theory | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Paul Farhi (May 15, 2015). "The ever-iconoclastic, never-to-be-ignored, muckraking Seymour Hersh". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Shafer, Jack (May 11, 2015). "Sy Hersh, Lost in a Wilderness of Mirrors". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Bergen rebuts claims that Obama lied about bin Laden". CNN. May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Chotiner, Isaac (May 13, 2015). "'I am not backing off anything I said': an interview with Seymour Hersh". Slate. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Lerner, Adam (May 11, 2015). "Former top CIA official on bin Laden raid account: 'It's all wrong'". Politico. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Bender, Bryan; Philip Ewing (May 11, 2015). "U.S. officials fuming over Hersh account of Osama bin Laden raid". Politico. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Timm, Trevor (May 15, 2015). "The media's reaction to Seymour Hersh's bin Laden scoop has been disgraceful". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Mir, Amir (May 12, 2015). "Brig Usman Khalid informed CIA of Osama's presence in Abbottabad". The News International. Karachi. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Withnall, Adam (May 14, 2015). "Osama bin Laden killing: Pakistan officials 'out' spy who gave away al-Qaeda leader's location". The Independent. London. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Michael Calderone (December 8, 2013). "New Yorker, Washington Post Passed On Seymour Hersh Syria Report". HuffPost US. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (December 9, 2013). "The Other Questions Raised by Seymour Hersh's Syria Scoop". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- Gray, Rosie (December 8, 2013). "Report: Obama Administration Knew Syrian Rebels Could Make Chemical Weapons". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- Sink, Justin (December 9, 2013). "WH: Hersh report on Syria 'simply false'". The Hill. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- Higgins, Eliot; Kaszeta, Dan (April 22, 2014). "It's clear that Turkey was not involved in the chemical attack on Syria". the Guardian. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Seymour M Hersh. "Trump's Red Line". Welt am Sonntag. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- "Whatever happened to Seymour Hersh?". Prospect Magazine. July 17, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- Seymour M Hersh. "We got a fuckin' problem". Welt am Sonntag. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- Higgins, Eliot (June 25, 2017). "Will Get Fooled Again – Seymour Hersh, Welt, and the Khan Sheikhoun Chemical Attack". Bell¿ngcat. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- George Monbiot A lesson from Syria: it's crucial not to fuel far-right conspiracy theories, The Guardian, November 15, 2017

- Midolo, Emanuele (February 8, 2023). "US bombed Nord Stream gas pipelines, claims investigative journalist Seymour Hersh". The Times. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- "White House Denies Seymour Hersh Report That U.S. Sabotaged Nord Stream Pipelines". Democracy Now!. February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- "US and Norway blew up the Nord Stream Pipelines: Seymour Hersh". Helsinki Times. February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- Scheidler, Fabian. "US Blew Up Nord Stream Pipeline Because Ukraine War Wasn't Going Well for the West: Seymour Hersh". The Wire (India). Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- "Russia: U.S. has questions to answer over Nord Stream explosions". Reuters. February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- "White House says blog post on Nord Stream explosion 'utterly false'". Reuters. February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- "Avviser Seymour Hershs avsløring: – Ren fiksjon" (In Norwegian; "Rejecting disclosure from Seymour Hersh: - Pure fiction), Journalisten, 9 February 2023

- ^ "Forsvaret ut mot «oppspinn» om Nord Stream-sprengningen: – De norske flyene har aldri vært i området" (In Norwegian; "The Norwegian Defence reacting about "nonsense" about the Nord Stream explosion: - The Norwegian planes have never been in the area"), Filter Nyheter, 10 February 2023

- Skinner, Anna (February 9, 2023). "Nord Stream attack: Senator raises alarms about alleged U.S. involvement". Newsweek. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- Faulconbridge, Guy; Soldatkin, Vladimir (February 9, 2023). "Kremlin says those behind Nord Stream blasts must be punished". Reuters. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- "Nord-Stream-Debatte im Bundestag: Wo sitzt der Feind?". Berliner Zeitung. February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ "Dziennikarz śledczy: To USA i Norwegia stoją za wybuchami gazociągów Nord Stream". Nettavisen. February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Reporter-Legende sicher: USA haben Nordstream gesprengt". Nau.ch. February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Sy Hersh Effect".

- Pirani, Simon (February 16, 2023). "The Nord Stream Pipeline Explosions: Challenging False Narratives". New Politics. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- Vlahos, Kelly (February 16, 2023). "The Sy Hersh effect: killing the messenger, ignoring the message". Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- "Jacobin Interview".

- "Democracy Now! Interview".

- "Radio War Nerd Interview".

- Seymour M. Hersh (February 25, 2007). "The Redirection". The New Yorker.

- Sivan, Emmanuel (June 20, 2007). "Thus are reports about the Mideast generated". Haaretz. Haaretz Daily Newspaper Ltd. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- Gabriel Schoenfeld. ""Blowback" in Lebanon?". Commentary Magazine.

- ^ Folkenflik, David (August 16, 2017). "The Man Behind The Scenes In Fox News' Discredited Seth Rich Story". NPR. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- Folkenflik, David (August 1, 2017). "Behind Fox News' Baseless Seth Rich Story: The Untold Tale". NPR. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- Livingstone, Jo. "The Seymour Hersh Weekly". newrepublic.com. The New Republic. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ El-Gingihy, Youssef (July 31, 2018). "Legendary journalist Seymour Hersh on novichok, Russian links to Donald Trump and 9/11". The Independent. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Hersh's Dark Camelot", Los Angeles Times, December 28, 1997

- ^ "Many Sources But No Meat", Amir Taheri, The Sunday Telegraph, September 19, 2004

- ^ Suellentrop, Chris (April 18, 2005). "Sy Hersh Says It's Okay to Lie (Just Not in Print)". nymag.com. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Moyer, Justin (May 13, 2015). "Sy Hersh, journalism giant: Why some who worshiped him no longer do". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- "CNN.com - Hersh: U.S. mulls nuclear option for Iran". www.cnn.com. April 10, 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- Fisher, Max (May 11, 2015). "The many problems with Seymour Hersh's Osama bin Laden conspiracy theory". Vox. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Kirchick, James (May 12, 2015). "A Crank Theory of Seymour Hersh". Slate Magazine. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Bender, Bryan; Ewing, Philip. "U.S. officials fuming over Hersh account of bin Laden raid". POLITICO. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "The Avenger: Sy Hersh, Then and Now" Archived January 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Scott Sherman, Columbia Journalism Review, July/August 2003 Pages 34–43

- Farhi, Paul (May 15, 2015). "The ever-iconoclastic, never-to-be-ignored, muckraking Seymour Hersh". The Washington Post.

- George Orwell Award, ncte.org. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Past George Polk Award Winners, liu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- International Reporting - The Pulitzer Prizes, pulitzer.org. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Past George Polk Award Winners, liu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- 04/11/1983 - Seymour Hersh to Discuss Journalism and Foreign Policy Policy, eiu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Past George Polk Award Winners, liu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- EXPOSE OF C.I.A. WINS THE HILLMAN AWARD, nytimes.com, 3 May 1975. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Past George Polk Award Winners, liu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- 1983 - The National Book Critics Circle Award, bookcritics.org. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Seymour Hersh, nationalpress.org. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Past George Polk Award Winners, liu.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Seymour Hersh, newyorker.com. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Ridenhour courage prize recipient 2005

- American Library Association, Notable Books Council, The List for 2005.

- Ray McGovern: Seymour Hersh Honored for Integrity, Consortiumnews, September 1, 2017

External links

| Laureates of the Sam Adams Award | |

|---|---|

|

| Recipients of the Orwell Award | |

|---|---|

| 1975–1999 |

|

| 2000–present |

|

- 1937 births

- Living people

- American investigative journalists

- American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- American war correspondents of the Vietnam War

- American people of the Vietnam War

- American war correspondents

- The Atlantic (magazine) people

- Espionage writers

- George Polk Award recipients

- Jewish American journalists

- Jewish American writers

- Journalists from Illinois

- Mỹ Lai massacre

- The New York Times writers

- The New Yorker staff writers

- Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting winners

- University of Chicago alumni

- Writers from Chicago

- 20th-century American journalists

- American male journalists