This is an old revision of this page, as edited by WIN (talk | contribs) at 09:00, 14 March 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:00, 14 March 2007 by WIN (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Indo-Aryan migration (disambiguation).| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Languages

|

| Philology |

Origins

|

|

Archaeology

Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

Indo-Aryans Iranians East Asia Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

Religion and mythology

Others

|

Indo-European studies

|

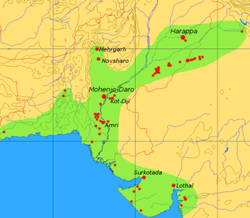

Indo-Aryan migration refers to the hypothetical expansion of speakers of Indo-Aryan languages following the split from Proto-Indo-Iranian. It notably concerns theories surrounding the intrusion of Indo-Aryan languages to the Indian subcontinent in the early 2nd millennium BC.

Based on linguistic evidence, most scholars have argued that Indo-Aryan speakers migrated to northern India following the breakup of Proto-Indo-Iranian and the subsequent Indo-Iranian expansion out of Central Asia (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help). These scholars argue that, in India, the Indo-Aryans interacted with the remnants of the Indus Valley civilization, a process that gave rise to Vedic civilization (Parpola 2005) harv error: no target: CITEREFParpola2005 (help). The linguistic facts of the situation are little disputed by the relevant scholars (Bryant 2001, p. 73–74) harv error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help). Linguistic data alone cannot determine whether this migration was peaceful or invasive. Different linguists have argued for either, or for a combination of both, on extra-linguistic grounds, but contemporary consensus clearly favours "gradual migration" over "military invasion".

Archaeological data indicates that a shift by Indus Valley cultural groups is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in South Asia before the first half of the first millennium B.C.. There is no archaeological or biological evidence for invasions or mass migrations of Indo-Aryan people into India.

The alternative to Indo-Aryan migration is known as "Out of India" which argues for opposite migration. This theory has little academic support.

History and political background

Main article: Aryan invasion theory (history and controversies)In the earliest phase of Indo-European studies, Sanskrit was assumed to be very close to (if not identical with) hypothetical Proto-Indo-European language. Its geographical location also fitted the then-dominant Biblical model of human migration, according to which Europeans were descended from the tribe of Japhet, which was supposed to have expanded from Mount Ararat after the Flood. Iran and northern India seemed to be likely early areas of settlement for the Japhetites.

In the course of the 19th century, as the field of historical linguistics progressed, and Bible-based models of history were abandoned, it became clear that Sanskrit could no longer be given priority. In line with late 19th century ideas, an Aryan 'invasion' was made the vehicle of the language transfer. Max Muller estimated the date to be around 1500–1200 BC, a date also supported by more recent scholars.

The Indus Valley civilization, discovered in the 1920s, was unknown to 19th century scholars. The discovery of the Harappa and Mohenjo-daro sites changed the theory from an invasion of implicitly advanced Aryan people on an aboriginal population to an invasion of nomadic barbarians on an advanced urban civilization, an argument associated with the mid-20th century archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. The decline roughly contemporaneous to the proposed migration movement was seen initially as an independent confirmation of these early suggestions (compare the causal relations between the decline of the Roman Empire and the Germanic Migration Period).

Among the archaeological signs claimed by Wheeler to support the theory of an invasion are the many unburied corpses found in the top levels of Mohenjo-daro. They were interpreted by Wheeler as victims of a conquest of the city, but Wheeler's interpretation is no longer accepted by many scholars (e.g. Bryant 2001). Wheeler himself expressed no certainty, but wrote, in a famous phrase, that "Indra stands accused".

In the later 20th century, ideas were refined, and so now migration and acculturation are seen as the methods whereby Indo-Aryan spread into northwest India around 1700 BCE. These changes are exactly in line with changes in thinking about language transfer in general, such as the migration of the Greeks into Greece (between 2100 and 1600 BCE), or the Indo-Europeanization of Western Europe (between 2200 and 1300 BCE).

Political debate

The debate over such a migration, and the accompanying influx of elements of Vedic religion from Central Asia is still politically charged and hotly debated in India. Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) organizations, especially, remain opposed to the concept, for political, religious, and scientific reasons, while many Indian Marxists and a fraction of the Dalit Movement support the theory in opposition to the Hindu nationalists, mostly for political reasons. Outside India, the perceived political overtones of the theory are not as pronounced, and it is discussed in the larger framework of Indo-Iranian and Indo-European expansion.

Linguistics

Linguists have several rules of thumb they use to gauge the place of origin of a family. One is that the area of highest linguistic diversity of a language family is usually fairly close to the area of its origin (Dyen 1965, p. 15 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDyen1965 (help) cited in Bryant 2001, p. 142 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)); thus, for example, while the modern nation with the highest number of speakers of Germanic languages is the United States, the highest diversity of longstanding Germanic languages is found in northern Europe. This is due to the fact that placing the origin of a language family in the area of least heterogeneity requires postulating the fewest number of migrations, and because of the unlikelihood of several linguistic features developing in an area without leaving any representatives behind. By this criterion, India, home to only the Indo-Aryan subfamily, seems to be an exceedingly unlikely candidate for the origin of the Indo-European languages. JP Mallory (1989) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help) notes that "t is far more logical to imagine that the Indo-Iranian languages had moved away from the mass of other Indo-European languages rather than the converse, and to argue otherwise is to engage in the same type of absurdity as assuming that the Finno-Ugric languages originated in Hungary." Conversely, such a criterion suggests a North Indian homeland for the Dravidian languages (McAlpin 1979) harv error: no target: CITEREFMcAlpin1979 (help). However, extinctions of unrecorded languages may affect this measure. Most linguists believe Indo-European to have originated somewhere around the Black Sea (Mallory 1989, p. 177–185) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help): a favorite candidate is the Kurgan hypothesis (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help).

Dialectical variation

It has long been recognized that a binary tree model cannot capture all linguistic alignments; certain areal features cut across language groups and are better explained through a model treating linguistic change like waves rippling out through a pond. This is true of the Indo-European languages as well. Various features originated and spread while Proto-Indo-European was still a dialect continuum (Hock 1991, p. 454) harv error: no target: CITEREFHock1991 (help). These features sometimes cut across sub-families: for instance, the instrumental, dative, and ablative plurals in Germanic, Baltic and Slavic feature endings beginning with -m-, rather than the usual -*bh-, e.g. Old Church Slavic instrumental plural synŭ-mi 'with sons' (Fortson 2004, p. 106) harv error: no target: CITEREFFortson2004 (help), despite the fact that the Germanic languages are centum languages, while Baltic and Slavic are satem languages.

There is a close relationship between the dialectical relationship of the Indo-European languages and the actual geographical arrangement of the languages in their earliest attested forms that makes an Indian origin for the family unlikely (Hock 1999) harv error: no target: CITEREFHock1999 (help). Given the geographic barriers separating the subcontinent from the rest of Eurasia, such as the Hindu Kush mountains and the existence of the various Indo-European sub-families, an Indian Urheimat would require several successive staggered migrations (c.f. Out of India theory). However, this would destroy the close arrangement between archaic shared linguistic features and geographical arrangement noted above. This arrangement is better explained by a radial expansion of the Indo-Europeans, a corollary of which is the migration of Indo-Aryan speakers into the subcontinent.

Substrate influence

Main article: Dravidian substratum in SanskritMost of the languages of North India belong to a single language family, the Indo-Aryan subgroup of the Indo-European family of languages. The languages of South India belong to a different language family, the Dravidian languages.

The presence of retroflex consonants in Vedic Sanskrit is generally taken by linguists to indicate the influence of a non-Indo-European speaking substratum population (Parpola 2005) harv error: no target: CITEREFParpola2005 (help).

Kuiper (1991) extracted 383 words (about 4% of Rigvedic vocabulary) that he classified as loan words. Oberlies (1994) counts a total of 344 "secure" non-Indo-European words in the Rigveda. Subtracting local non-Indo-European toponyms and personal names, there is a remaining total of 211-250 "foreign" lexemes in Rigvedic Sanskrit, amounting to ca. 2% of the vocabulary. Mayrhofer identifies a "prefixing" language, based on recurring prefixes like ka- or ki-, compared to the Austro-Asiatic article by Witzel (1999:12).

P. Thieme (1994) and R.P. Das (1995) have rejected Kuiper's list in total.

Chronology

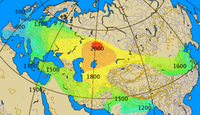

The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have often been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations. The Gandhara Grave (GGC), Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and Painted Grey Ware (PGW) cultures are candidates for cultures associated with Indo-Aryan movements. The Indo-Aryan migration is dated subsequent to the Mature Harappan culture and the arrival of Indo-Aryans in the Indian subcontinent dated during the Late Harappan period. Based on linguistic data, many scholars argue that the Indo-Aryan languages were introduced to India in the 2nd millennium BCE. The standard model for the entry of the Indo-European languages into India is that this first wave went over the Hindu Kush, forming the Gandhara grave (or Swat) culture, either into the headwaters of the Indus or the Ganges (probably both). The language of the Rigveda, the earliest stratum of Vedic Sanskrit is assigned to about 1500-1200 BCE (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help).

The separation of Indo-Aryans proper from Proto-Indo-Iranians has been dated to roughly 2000 BCE–1800 BCE. It is believed Indo-Aryans reached Assyria in the west and the Punjab in the east before 1500 BC: the Indo-Aryan Mitanni rulers appear from 1500 in northern Mesopotamia, and the Gandhara grave culture emerges from 1600. This suggests that Indo-Aryan tribes would have had to be present in the area of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (southern Turkmenistan/northern Afghanistan) from 1700 BC at the latest (incidentally corresponding with the decline of that culture).

The Gandhara grave culture is the most likely locus of the earliest Indo-European presence east of the Hindu Kush of the bearers of Rigvedic culture, and based on this Parpola (1998) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFParpola1998 (help) assumes an immigration to the Punjab ca. 1700-1400, but he also postulates a first wave of immigration from as early as 1900 BC, corresponding to the Cemetery H culture.

Rajesh Kochhar (2000:185–186) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFKochhar2000 (help) argues that there were three waves of Indo-Aryan immigration that occurred after the mature Harrapan phase: the Murghamu (BMAC) related people who entered Baluchistan at Pirak, Mehrgarh south cemetery, etc. and later merged with the post-urban Harappans during the late Harappans Jhukar phase; the Swat IV that co-founded the Harappan Cemetery H phase in Punjab and the Rigvedic Indo-Aryans of Swat V that later absorbed the Cemetery H people and gave rise to the Painted Grey Ware culture. He dates the first two to 2000-1800 BCE and the third to 1400 BCE.

Early Indo-Aryans

See also: MitanniThe earliest written evidence for an Indo-Aryan language dates to about 1500 BCE (Mallory & Mair 2000) harv error: no target: CITEREFMalloryMair2000 (help) and is found in northern Syria (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help) in Hittite records regarding one of their neighbors, the Hurrian-speaking Mitanni(Mallory & Mair 2000) harv error: no target: CITEREFMalloryMair2000 (help). In a treaty with the Hittites, the king of Mitanni, after swearing by a series of Hurrian gods, swears by the gods Indara, Mitraśil, Naśatianna and Uruvanaśśil, who correspond to the Vedic gods Indra, Mitra, Nāsatya and Varuṇa(Mallory & Mair 2000) harv error: no target: CITEREFMalloryMair2000 (help). Contemporary equestrian terminology, as recorded in a horse-training manual whose author is identified as "Kikkuli the Mitannian" contains Indo-Aryan loanwords. The personal names and gods of the Mitanni aristocracy also bear traces of Indo-Aryan (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help). In 1960, Paul Thieme demonstrated to the satisfaction of most scholars that this vocabulary was specifically Indo-Aryan, as opposed to Iranian or Indo-Iranian (Bryant 2001, p. 136) harv error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help). Because of this association of Indo-Aryan with horsemanship and the Mitanni aristocracy, it is generally presumed that, after superimposing themselves as rulers on a native Hurrian-speaking population about the 15th-16th centuries BCE, Indo-Aryan charioteers were absorbed into the local population and adopted the Hurrian language (Mallory 1989 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help), Mallory & Mair 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMalloryMair2000 (help)).

Brentjes argues that there is not a single cultural element of central Asian, eastern European, or Caucasian origin in the Mitannian area and associates with an Indo-Aryan presence the peacock motif found in the Middle East from before 1600 BCE and possible as long ago as 2100 BCE (Brentjes 1981, p. 147 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBrentjes1981 (help) in Bryant 2001, p. 137 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)).

However, received opinion rejects the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of Mitanni came from the Indian subcontinent as well as the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of the Indian subcontinent came from the territory of Mitanni, leaving migration from the north the only likely scenario (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help).

Textual References

Rigveda

The Rigveda is by far the most archaic testimony of Vedic Sanskrit. It is generally believed that the Rigveda represents a pastoral or nomadic, mobile culture (Bryant 2001, p. 91) harv error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help), still centered on the Indo-Iranian Soma cult and fire worship. With all the effort to glimpse historical information from the hymns of the Rigveda, it should not be forgotten that the purpose of these hymns is ritualistic, not historiographical or ethnographical, and any information about the way of life or the habitat of their authors is incidental and philologically extrapolated from the context (e.g. Leach 1990 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLeach1990 (help)).

Rigvedic society as pastoral society

The mobile nature of the Vedic religion is illustrated by the laying out of the ritual precinct as part of the ritual, rather than the existence of fixed temples. This holds for the invitation of Indra to the Soma ritual as well as for the Agnicayana, the piling-up of the fire altar. Cities or fortresses (púr) are mentioned in the Rigveda mainly as the abode of hostile peoples, while the Aryan tribes live in vísa, a term translated as "settlement, homestead, house, dwelling", but also "community, tribe, troops" (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help).

Indra in particular is described as destroyer of fortresses, e.g. RV 4.30.20ab:

- satám asmanmáyinaam / purām índro ví asiyat

- "Indra overthrew a hundred fortresses of stone."

The Rigveda does contain some phrases referring to elements of an urban civilization, other than the mere viewpoint of an invader aiming at sacking the fortresses. These references become increasingly frequent in the younger books 1 and 10, linguistically dated as contemporary to the early parts of the Atharvaveda and the mantras of the Yajurveda. Here, for example, Indra is compared to the lord of a city (purapatis) in RV 1.173.10, a ship with a hundred oars is mentioned in 1.116 and metal forts (puras ayasis) in 10.101.8. Since the Vedic books appear to have been composed over a long period of gradual change, rather than being a snapshot of society at one particular moment, these late Rigvedic books may indeed describe an urbanized amalgamation of pastoral Indo-Aryan culture with indigenous, Late Harappan elements even in the view of proponents of immigration, roughly representing the early phase of the Kuru kingdom (ca. 12th century BC). Furthermore, there were also cities in the Post-Harappan period in the Punjab region.

However, according to S.P. Gupta (1996), "ancient civilizations had both the components, the village and the city, and numerically villages were many times more than the cities. (...) if the Vedic literature reflects primarily the village life and not the urban life, it does not at all surprise us.". Gregory Possehl (1977) argued that the "extraordinary empty spaces between the Harappan settlement clusters" indicates that pastoralists may have "formed the bulk of the population during Harappan times" (Bryant 2001, p. 195) harv error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help). Agriculturalists, pastoralists as well as the city and village life may have coexisted in the same region. Such a view would imply that the only testimony surviving of Harappan times is not from the urban centers, but of the the rituals of rural pastoralists living between the cities.

Rigvedic reference to migration

There is no explicit mention of an outward or inward migration in the Rigveda. In RV 7.6.3, Agni turned the godless and the Dasyus westward, and not southward, as would be required by some versions of the AIT. Some of the tribes that fought against Sudas on the banks of the Parusni River during the Dasarajna battle have maybe migrated to western countries in later times, as they are possibly connected with some Iranian peoples (e.g. the Pakthas, Bhalanas).

While the Avesta does mention an external homeland of the Zoroastrians, the Rigveda does not explicitly refer to an external homeland or to a migration. Later texts than the Rigveda (such as the Puranas) seem to be more centered in the Ganges region. This shift from the Punjab to the Gangetic plain continues the Rigvedic tendency of eastward expansion, but does of course not imply an origin beyond the Indus watershed.

Rigvedic Rivers and Reference of Samudra

The geography of the Rigveda seems to be centered around the land of the seven rivers. While the geography of the Rigvedic rivers is unclear in the early mandalas, the Nadistuti hymn is an important source for the geography of late Rigvedic society.

The Sarasvati River is one of the chief Rigvedic rivers. The Nadistuti hymn in the Rigveda mentions the Sarasvati between the Yamuna in the east and the Sutlej in the west, and later texts like the Mahabharata mention that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert.

Most scholars agree that at least some of the references to the Sarasvati in the Rigveda refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River, while the Helmand is often quoted as the locus of the early Rigvedic river. Whether such a transfer of the name has taken place, either from the Helmand to the Ghaggar-Hakra, or conversely from the Ghaggar-Hakra to the Helmand, is a matter of dispute. Identification of the early Rigvedic Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra before its drying up would place the Rigveda well before 1700 BC, and thus well outside the range commonly assumed by Indo-Aryan migration theory.

A non-Indo-Aryan substratum in the river-names and place-names of the Rigvedic homeland would support an external origin of the Indo-Aryans. However, most place-names in the Rigveda and the vast majority of the river-names in the north-west of India are Indo-Aryan (Bryant 2001).

Iranian Avesta

The religious practices depicted in the Rgveda and those depicted in the Avesta, the central religious text of Zoroastrianism—the ancient Iranian faith founded by the prophet Zarathustra—have in common the deity Mitra, priests called hotr in the Rgveda and zaotr in the Avesta, and the use of a hallucinogenic compound that the Rgveda calls soma and the Avesta haoma. However, the Indo-Aryan deva, meaning 'god,' is cognate with the Iranian daeva, meaning 'demon'. Likewise, the Indo-Aryan asura, meaning 'demon,' is cognate with the Iranian ahura, meaning 'god,' suggesting that, at some point, a rivalry between Indo-Aryans and Iranians that found religious expression, as the Indologist Thomas Burrow has proposed.

Two alternative dates for Zarathustra can be found in Greek sources: 5000 years before the Trojan War, i.e. 6000 BCE, or 258 years before Alexander, i.e. the 6th century BCE, the latter of which used to provide the conventional dating but has since been traced to a fictional Greek source. Linguists such as Burrow argue that the strong similarity between the Avestan language of the Gathas—the oldest part of the Avesta—and the Vedic Sanskrit of the Rgveda pushes the dating of Zarathustra or at least the Gathas closer to the conventional Rgveda dating of 1500–1200 BCE, i.e. 1100 BCE, possibly earlier. Boyce concurs with a lower date of 1100 BCE and tentatively proposes an upper date of 1500 BCE. Gnoli dates the Gathas to around 1000 BCE, as does J.P. Mallory, with the caveat of a 400 year leeway on either side, i.e. between 1400 and 600 BCE. Therefore the date of the Avesta could also indicate the date of the Rigveda.

There is mention in the Avesta of Airyanem Vaejah, the legendary homeland of the Aryans as well as Zarathustra himself. Gnoli's interpretation of geographic references in the Avesta situates the Airyanem Vaejah in the Hindu Kush. For similar reasons, Boyce excludes places north of the Syr Darya and western Iranian places. With some reservations, Skjaervo concurs that the evidence of the Avestan texts makes it impossible to avoid the conclusion that they were composed somewhere in northeastern Iran. Michael Witzel points to the central Afghan highlands. Humbach derives Vaejah from cognates of the Vedic root "vij," suggesting the region of a fast-flowing river. Gnoli considers the lower Oxus region, south of the Aral Sea to be an outlying area in the Avestan world. However, according to Mallory and Mair, the probable homeland of Avestan is, in fact, the area south of the Aral Sea, which just happens to be the region of a fast-flowing river.

Other Hindu texts

Indologists have noted that "there is no textual evidence in the early literary traditions unambiguously showing a trace" of an Indo-Aryan migration. Texts like the Puranas and Mahabharata belong to a later period than the Rigveda, making their evidence less sufficient to be used for or against the Indo-Aryan migration theory.

According to the Yajur Veda, Yajnavalkya (one of the Vedic Seers) lived in the eastern region of Mithila. Aitareya Brahmana 33.6.1. records that Vishvamitra's sons migrated to the north, and in Shatapatha Brahmana 1:2:4:10 the Asuras were driven to the north.

Manu was said to be a king from Dravida. In the legend of the flood he stranded with his ship in Northwestern India or the Himalayas. The Vedic land (e.g. Aryavarta, Brahmavarta) is located in Northern India or at the Sarasvati and Drsadvati River, according to Hindu texts. In the Mahabharata Udyoga Parva (108), the East is described as the homeland of the Vedic culture, where "the divine Creator of the universe first sang the Vedas." The legends of Ikshvaku, Sumati and other Hindu legends may have their origin in South-East Asia.

Puranas

The evidence from the Puranas is often disputed because they are a comparably late text. They are often dated from c.400 to c.1000 CE. The Rgveda dates from before 1200 BCE. Thus the Rgveda and the Puranas are separated by approximately 1600 to 2200 years, though scholars argue that some contents of the Puranas may date to an earlier period.

The Puranas record that Yayati left Prayag (confluence of Ganga & Yamuna) and conquered the region of Saptha Sindhu. His five sons Yadu, Druhyu, Puru, Anu and Turvashu became the main tribes of the Rigveda.

The Puranas also record that the Druhyus were driven out of the land of the seven rivers by Mandhatr and that their next king Ghandara settled in a north-western region which became known as Ghandara. The sons of the later Druhyu king Pracetas finally migrate to the region north of Afghanistan. This migration is recorded in several Puranas.

Vedic and Puranic genealogies

The Vedic and Puranic genealogies indicate a greater antiquity of the Vedic culture. The Puranas themselves state that these lists are incomplete. But the accuracy of these lists is disputed. In Arrian's Indica, Megasthenes is quoted as stating that the Indians counted from Shiva (Dionysos) to Chandragupta Maurya (Sandracottus) "a hundred and fifty-three kings over six thousand and forty-three years." The Brhadaranyaka Upanishad (4.6.), ca. 8th century BCE, mentions 57 links in the Guru-Parampara ("succession of teachers"). This would mean that this Guru-Parampara would go back about 1400 years, although the accuracy of this list is disputed. The list of kings in Kalhana's Rajatarangini goes back to the 19th century BCE.

Archaeology

Northwestern India always had cultural exchanges and trade contacts with Afghanistan and other western regions. About 1800 BCE, there is a major cultural change in the Swat Valley with the introduction of new ceramics and two new burial rites: flexed inhumation in a pit and cremation burial in an urn which, according to early Vedic literature, were both practiced in early Indo-Aryan society. The economy of the Swat culture not only includes the horse, but there are two horse burials as well as other horse-trappings.

This evidence is not sufficient to suggest an "invasion" or "mass migration". J. M. Kenoyer and many other archaeologists have pointed out that "current evidence does not support a pre- or proto-historic Indo-Aryan invasion of southern Asia. Instead, there was an overlap between Late Harappan and post-Harappan communities, with no biological evidence for major new populations." and the intrusion of an Indo-Aryan superstrate would not have been sufficient to displace indigenous culture: some cultural traits associated with Vedic culture according to Erdosy "originate in different places at different times and circulate widely" and it is therefore "impossible ... to regard the widespread distribution of certain beliefs and rituals ... as evidence of population movements."

Mallory (1997) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFMallory1997 (help) has pointed out that archaeological continuity can be supported for every Indo-European-speaking region of Eurasia, and that such an absence of evidence is not evidence for the absence of a migration, as the Indo-Europeans must have come from somewhere. Furthermore, several historically documented migrations, such as those of the Helvetii to Switzerland, the Huns into Europe, or Gaelic-speakers into Scotland are not attested in the archaeological record. (Anthony 1986 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAnthony1986 (help), Sinor 1990, p. 203 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSinor1990 (help), Mallory 1989, p. 166 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help)). Finally, such arguments cut both ways, since there is no evidence of any east-to-west migration of archaeological cultures, the only other possibility that could be consistent with the existence of the Indo-European language family (Bryant 2001, p. 236) harv error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help).

Proto-Indo-Iranians

Main article: Indo-IraniansScholars commonly accept the identification of the Andronovo-Sintashta-Petrovka culture (ca. 2200 BC–1600 BC) as Indo-Iranian, i.e. ancestral to both Indo-Aryans and Iranians. Proto-Indo-Iranians are usually identified with the Sintashta-Petrovka culture of Russia and Kazakhstan. It is there that the earliest chariots are found. The follow-up Andronovo culture and BMAC correspond to the earliest phase of the rapid expansion that would reach into the Caucasus, the Iranian plateau, Afghanistan, and the Indian Subcontinent.

Asko Parpola (1988) has argued that the Dasas were the "carriers of the Bronze Age culture of Greater Iran" living in the BMAC and that the forts with circular walls destroyed by the Vedic Aryans of the Rigveda were actually located in the BMAC. Other scholars have argued that cultural links between the BMAC and the Indus Valley can also be explained by reciprocal cultural influences uniting the two cultures.

Other scholars have argued that the Andronovo culture cannot be associated with the Indo-Aryans of India or with the Mitannis because the Andronovo culture took shape too late and because no actual traces of their culture (e.g. warrior burials or timber-frame materials of the Andronovo culture) have been found in India or Mesopotamia. The archaeologist J. P. Mallory (1998) found it "extraordinarily difficult to make a case for expansions from this northern region to northern India" and remarked that the proposed migration routes "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans". The evidence disputing this argument, is both linguistic and archaeological (for linguistic arguments, see e.g. Hans Hock in Bronkhorst & Deshpande 1999)

Indus Valley Civilization

Indo-Aryan migration into the northern Punjab is thus approximately contemporaneous to the final phase of the decline of the Indus-Valley civilization (IVC). Many scholars have argued that the historical Vedic culture is the result of an amalgamation of the immigrating Indo-Aryans with the remnants of the indigenous civilization, such as the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. Such remnants of IVC culture is not yet present in the Rigveda, with its focus on chariot warfare and nomadic pastoralism in stark contrast with an urban civilization.

The decline of the IVC from about 1900 BC is not universally accepted to be connected with Indo-Aryan immigration. A regional cultural discontinuity occurred during the second millennium BC and many Indus Valley cities were abandoned during this period, while many new settlements began to appear in Gujarat and East Punjab and other settlements such as in the western Bahawalpur region increased in size. Shaffer and Liechtenstein stated that: "This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in South Asia before the first half of the first millennium B.C..". This could have been caused by ecological factors, such as the drying up of the Ghaggar-Hakra River and increased aridity in Rajasthan and other places. The Indus River also began to flow east and floodings occurred. Jim Shaffer and other scholars have argued that these "internal cultural adjustments" could reflect "altered ecological, social and economic conditions affecting northwestern and north-central South Asia" and do not necessarily imply migrations.

The opinion of the majority of professional archaeologists working in South Asia seems to be that the archaeological data is inconclusive or not supportive with regard to an Indo-Aryan immigration connected with the decline of the IVC. Kenoyer argued: "Although the overall socioeconomic organization changed, continuities in technology, subsistence practices, settlement organization, and some regional symbols show that the indigenous population was not displaced by invading hordes of Indo-Aryan speaking people. For many years, the ‘invasions’ or ‘migrations’ of these Indo-Aryan-speaking Vedic/Aryan tribes explained the decline of the Indus civilization and the sudden rise of urbanization in the Ganga-Yamuna valley. This was based on simplistic models of culture change and an uncritical reading of Vedic texts..." At Kalibangan (at the Ghaggar river) the remains of what some writers claims to be fire altars have been unearthed. Some of their characteristics suggest that they could have been used for Vedic sacrifices. In addition the remains of a bathing place (suggestive of ceremonial bathing) have been found near the altars in Kalibangan. S.R. Rao found similar "fire altars" in Lothal which he thinks could have served no other purpose than a ritualistic one.

Horse and chariot

The spread of Indo-Aryan languages has been connected with the spread of the chariot in the first half of the second millennium BC. Elements supposedly introduced to India in the course of the migration include the Soma cult, as well as the horse and chariot.

The emergence of the Swat culture around 1800 BCE, with its new burial rites and the introduction of the horse is a major candidate for early Indo-Aryan presence.

Attempts of proponents of continuity to portray the Rigvedic culture as native to the subcontinent, such as identification of horses or chariots in Indus Valley Civilization art, have met with little or no acceptance from Indologists .

The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) also shows a very limited presence of the horse around 2000 BC and has been identified as Indo-Iranian "Proto-Dasa" by Parpola (1999), who ascribes the decline of the BMAC around 1700 to incursions of "Proto-Rigvedic" Indo-Aryans.

Archaeogenetics and physical anthropology

Main article: Genetics and Archaeogenetics of South Asia

Kenneth Kennedy (1984), who examined 300 skeletons from the Indus Valley civilization, concludes that the ancient Harappans “are not markedly different in their skeletal biology from the present-day inhabitants of Northwestern India and Pakistan”(p.102).

A later study finds no evidence of discontinuities in the skeletal record during and immediately after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization. The two discontinuities that Kennedy finds in the prehistoric skeletal record do not correspond to the second millennium BCE. The first of these discontinuities occurred between 6000-4500 BCE (a separation of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh), and the second occurred after 800 BCE (between 800-200 BCE). He concludes that "there is no evidence of demographic disruptions in the north-western sector of the subcontinent during and immediately after the decline of the Harappan culture. If Vedic Aryans were a biological entity represented by the skeletons from Timargarha, then their biological features of cranial and dental anatomy were not distinct to a marked degree from what we encountered in the ancient Harappans.” (1995: 54). Comparing the Harappan and Gandhara cultures, Kennedy remarks that: “Our multivariate approach does not define the biological identity of an ancient Aryan population, but it does indicate that the Indus Valley and Gandhara peoples shared a number of craniometric, odontometric and discrete traits that point to a high degree of biological affinity.” (1995: 49). The craniometric variables of prehistoric and living South Asians also showed an "obvious separation" from the prehistoric people of the Iranian plateau and western Asia (1995: 49).

Brian E. Hemphill and Alexander F. Christensen's study (1994) of the migration of genetic traits does not support a movement of Aryan speakers into the Indus Valley around 1500 BC. According to Hemphill's study, "Gene flow from Bactria occurs much later, and does not impact Indus Valley gene pools until the dawn of the Christian era." In a more recent study, Hemphill concludes that "the data provide no support for any model of massive migration and gene flow between the oases of Bactria and the Indus Valley. Rather, patterns of phenetic affinity best conform to a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange."

Chaubey et al. (2007) find that most of the India-specific mtDNA haplogroups show coalescent times of 40 to 60 millennia ago. Their virtual absence outside of India suggests only a limited gene-flow out of the subcontinent.

Alternate Theories

While Indo-Aryan migration as described in this article remains the most widely accepted scenario, independently of whether the Kurgan or Anatolian hypotheses of Indo-European origins are favoured. Nevertheless, competing Out of India scenarios postulating inverse direction of migration have been formulated.

Out of India Theory

Such "Out of India theories" have been proposed in recent times by Nicholas Kazanas and Koenraad Elst. Based mainly on alleged archaeological evidence and archaeoastronomy, the Out of India theory proposes the idea of the Indo-European languages originating in India. However, most linguists do not consider South Asia a serious candidate for Proto-Indo-European origin,.

Notes

- Mallory writes that "the great majority of scholars insist that the Indo-Aryans were intrusive into northwest India."

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1995) page 139, cited in Bryant 2001 page 232

- Kenoyer 1998. Shaffer 1995 and 1999

- He writes: "The Kurgan solution to the Indo-European problem would thus appear to solve our problem economically by providing a homeland congruent with the Proto-Indo-European culture as reconstructed by linguistics and occupying a geographical situation compatible with the most plausible expansion of Indo-European speakers. The archaeological evidence for the expansion is not limited to a few traits which might be easily dismissed as the result of exchange, but is rather all the major features of a culture in the course of expansion into alien territory. The warlike society of these mobile invaders provides the Kurgan people with an appropriate means of expansion and an explanation for their success at colonizing vast areas.

"The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is the solution one encounters in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse.…there is no alternative homeland from which archaeologists would derive all of the cultures of our late Indo-European territory." - Michael Witzel, Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic) EJVS VOL. 5 (1999), ISSUE 1 (September)

- Michael Witzel, Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic) EJVS VOL. 5 (1999), ISSUE 1 (September)

- The hunt for foreign words in the Rigveda’ (IIJ 38, 1995, 207–238)

- StBoT 41 (1995)

- Mallory writes: "It is highly improbable that the Indo-Aryans of Western Asia migrated eastwards, for example with the collapse of the Mitanni, and wandered into India, since there is not a shred of evidence — for example, names of non-Indic deities, personal names, loan words — that the Indo-Aryans of India ever had any contacts with their west Asian neighbours. The reverse possibility, that a small group broke off and wandered from India into Western Asia is readily dismissed as an improbably long migration, again without the least bit of evidence."

- "Ancient Indian history has been fashioned out of compositions, which are purely religious and priestly, which notoriously do not deal with history, and which totally lack the historical sense.(...) What would rise a smile if applied to Europe has been soberly accepted when applied to India." F.E. Pargiter 1922. But we must not forget that "the Vedic literature confines itself to religious subjects and notices political and secular occurrences only incidentally (...)". Cited in R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker (editors): The history and culture of the Indian people. Volume I, The Vedic age. Bombay : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan 1951, p.315, with reference to F.E. Pargiter.

- Mallory writes "...the culture represented in the earliest Vedic hymns bears little similarity to that of the urban society found at Harappa or Mohenjo-daro. It is illiterate, non-urban, non-maritime, basically uninterested in exchange other than that involving cattle, and lacking in any forms of political complexity beyond that of a king whose primary function seems to be concerned with warfare and ritual."

- Kazanas, A new date for the Rgveda, p.11

- e.g. MacDonnel and Keith, Vedic Index, 1912; Talageri 2000

- R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker (editors): The history and culture of the Indian people. Volume I, The Vedic age. Bombay : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan 1951, p.220

- Cardona 2002: 33-35; Cardona, George. The Indo-Aryan languages, RoutledgeCurzon; 2002 ISBN 0-7007-1130-9

- http://www.gisdevelopment.net/application/archaeology/site/archs0001pf.htm

- Mallory 1989

- Bryant 2001:131

- Mallory 1989

- Mallory 1989

- Bryant 2001:132

- Bryant 2001:132

- Mallory 1989

- Mallory and Mair 2000

- Bryant 2001:133

- Bryant 2001:133

- Bryant 2001:133

- Bryant 2001:133

- Bryant 2001:133

- Bryant 2001:327

- Bryant 2001:327

- Mallory and Mair 2000

- Cardona 2002: 33-35; Cardona, George. The Indo-Aryan languages, RoutledgeCurzon; 2002 ISBN 0-7007-1130-9

- (Bryant 2001: 64)

- Elst 1999, with reference to L.N. Renu

- e.g. Bhagavata Purana (VIII.24.13)

- e.g. Satapatha Brahmana, Atharva Veda

- e.g. RV 3.23.4., Manu 2.22, etc. Kane, Pandurang Vaman: History of Dharmasastra: (ancient and mediaeval, religious and civil law) — Poona : Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1962-1975

- Talageri 1993, The Aryan Invasion Theory, A Reappraisal

- Elst 1999, chapter 5, with reference to Bernard Sergent

- e.g. Bryant 2001:139

- There are also references to the Puranas in earlier texts like the Atharvaveda 11.7.24; Satapatha Brahmana 11.5.6.8. and 13.4.3.13; Chandogy Upanisad 3.4.1. Subhash Kak 1994, The astronomical of the Rgveda

- Talageri 1993, 2000; Elst 1999

- Bhagavata Purana 9.23.15-16; Visnu Purana 4.17.5; Vayu Purana 99.11-12; Brahmanda Purana 3.74.11-12 and Matsya Purana 48.9.

- see e.g. Pargiter 1979; Talageri 1993, 2000; Bryant 2001; Elst 1999

- see e.g. F.E. Pargiter 1979; P.L. Bhargava 1971, India in the Vedic Age, Lucknow: Upper India Publishing; Talageri 1993, 2000; Subhash Kak, 1994, The astronomical code of the Rgveda

- Matsya Purana 49.72; Pargiter 1922; Kak 1994 The astronomical code of the Rgveda

- Pliny: Naturalis Historia 6:59; Arrian: Indica 9:9

- (see Klaus Klostermaier 1989 and Arvind Sharma 1995)

- Elst 1999, with reference to Bernard Sergent

- e.g. Chakrabarti 1977 cited in Bryant 2001: 233 - 234

- Mallory 1989

- Mallory 1989

- "There is no archaeological or biological evidence for invasions or mass migrations into the Indus Valley between the end of the Harappan Phase, about 1900 BC and the beginning of the Early Historic period around 600 BC." Kenoyer 1998

- Cf. e.g. Shaffer 1984b/1995/1999, Bryant 2001

- Kenoyer 1991a

- Erdosy adds that "few of the traits show the northwest-southeast gradient in chronology predicted by our linguistic models." Erdosy 1995:12, also cited in Bryant 2001: 214-215

- Mallory 1989 "The identification of the Andronovo culure as Indo-Iranian is commonly accepted by scholars."

- Mallory and Mair 2000

- Parpola's hypothesis was also criticzed, see e.g. Sethna (1992) for a detailed critical review of Parpola's hypothesis.

- See e.g. Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. 2005; Bryant 2001:215-16

- like Brentjes (1981), Klejn (1974), Francfort (1989), Lyonnet (1993), Hiebert (1998), Bosch-Gimpera (1973) and Sarianidi (1993)

- (see Edwin Bryant 2001)

- (Mallory 1998; Edwin Bryant 2001: 216)

- (Shaffer and Liechtenstein 1995: 139)

- (Kenoyer 1995: 224)

- Jim Shaffer 1986: 230

- Most archaeologists interviewed by Edwin Bryant in India during the 1990's voiced such opinions. "This is part of a wider trend: archaeologists outside of South Asia are voicing similar views." Bryant 2001:231 ff. George Erdosy speaks of a "gulf still separating archaeologists and linguists" (Erdosy 1995: xiii), and that "we are a long way from fully correlating the linguistic and the archaeological evidence". (Erdosy 1995:13 ff) Erdosy, George (ed.) 1995. Cf. also Bronkhorst/Deshpande 1999, Bryant 2005

- J. M. Kenoyer: “The Indus Valley Tradition of Pakistan and Western India”, Journal of World Prehistory, 1991/4; cited in Bryant 2001:190

- (B.B. Lal. Frontiers of the Indus Civilization.1984:57-58)

- (S.R. Rao. The Aryans in Indus Civilization.1993:175)

- Mallory 1989 "horses and chariots were a technique of warfare apparently unknown to the Indus civilization."

- Sergent 1997:161 ff

- (Hemphill, Lukacs and Kennedy 1991, see also Kenneth Kennedy 1995)

- Hemphill 1998 "Biological Affinities and Adaptations of Bronze Age Bactrians: III. An initial craniometric assessment", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 106, 329-348.; Hemphill 1999 "Biological Affinities and Adaptations of Bronze Age Bactrians: III. A Craniometric Investigation of Bactrian Origins", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 108, 173-192

- Mallory 1989 "It is far more logical to imagine that the Indo-Iranian languages had moved away from the mass of other Indo-European languages rather than the converse, and to argue otherwise is to engage in the same type of absurdity as assuming that the Finno-Ugric languages originated in Hungary."

Bibliography and References

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Edwin Bryant and Laurie L. Patton (editors) (2005). Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge/Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1463-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Chakrabarti, D.K. The Early use of Iron In India. Dilip K. Chakrabarti.1992. New Delhi: The Oxford University Press.

- Chakrabarti, D.K. 1977b. India and West Asia: An Alternative Approach. Man and Environment 1:25-38.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Dhavalikar, M. K. 1995, "Fire Altars or Fire Pits?", in Sri Nagabhinandanam, Ed V Shivananda and M. K. Visweswara, Bangalore.

- Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate. Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-86471-77-4. ,

- George Erdosy (ed.) (1995). The Indo-Aryans of ancient South Asia. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 8121507901.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Template:Harvard reference

- Frawley, David (1995). The myth of the Aryan invasion of India. New Delhi: Voice of India. ISBN 81-85199-59-0.; --In Search of the Cradle of Civilization 1995. Quest Books; —Gods, Sages and Kings. 1991.Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, Wisconsin ISBN 0-910261-37-7; —The Rigveda and the History of India. 2001.; —Vedic Aryans and the Origins of Civilization (with N.S. Rajaram). Quebec: W.H. Press. 1995.

- Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X.: Aryas, Aryens et Iraniens en Asie Centrale. (2005) Institut Civilisation Indienne ISBN 2-86803-072-6

- Gupta, S.P. 1996. The Indus Sarasvati Civilization. Delhi: Pratibha Prakashan.

- Hemphill & Christensen: “The Oxus Civilization as a Link between East and West: A Non-Metric Analysis of Bronze Age Bactrain Biological Affinities”, paper read at the South Asia Conference, 3-5 November 1994, Madison, Wisconsin; p. 13.

- Hemphill, B.E. ; Lukacs, J.R.; and Kennedy, K.A.R. (1991). "Biological adaptations and affinities of the Bronze Age Harappans". Harappa Excavations 1986-1990. (ed. R.Meadow): 137–182.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Kak, Subhash. The Astronomical Code of the Rigveda; Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd (2000), ISBN 81-215-0986-6

- Kennedy, Kenneth 1984. “A Reassessment of the Theories of Racial Origins of the People of the Indus Valley Civilization from Recent Anthropological Data.” In Studies in the Archaeology and Palaeoanthropology of South Asia (99-107).

- --- 1995. “Have Aryans been identified in the prehistoric skeletal record from South Asia?”, in George Erdosy, ed.: The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, p.49-54.

- Kenoyer, J.M. 1991a. The Indus Valley Tradition of Pakistan and Western India. Journal of World Prehistory 5:331-385.

- Kenyoer, J.M. : (1991b) "Urban Process in the Indus Tradition: A Preliminary Model from Harappa." In Harappa Excavations 1986-1990 (29-60)

- Kenoyer, J.M. (1995). Interaction Systems, Specialized crafts and Culture Change. In: Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia. Ed. George Erdosy. ISBN 3-11-014447-6.

- Klostermaier, Klaus. 1989. A Survey of Hinduism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Kochhar, Rajesh (2000). The Vedic People: Their History and Geography. Sangam Books.

- Lal, B.B., (1984) Frontiers of the Indus Civilization.1984.

- Lal, B.B., (1998) New Light on the Indus Civilization, Aryan Books, Delhi 1998

- Lal, B.B. 2005. The Homeland of the Aryans. Evidence of Rigvedic Flora and Fauna & Archaeology, New Delhi, Aryan Books International.

- Lal, B.B. 2002. The Saraswati Flows on: the Continuity of Indian Culture. New Delhi: Aryan Books International

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Mallory, JP. 1998. A European Perspective on Indo-Europeans in Asia. In: The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern and Central Asia. Ed. Mair. Washingion DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Oppenheimer, Stephen; (2003) "The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey out of Africa" ,

- Pargiter, F.E. 1979. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. New Delhi: Cosmo.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- S.R. Rao. The Aryans in Indus Civilization.1993

- Sethna, K.D. 1992. The Problem of Aryan Origins. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-85179-67-0

- Shaffer, Jim : (1984), The Indo-Aryan Invasions: Cultural Myth and Archaeological Reality, in John R Lukacs (ed.) The People of South Asia: The Biological Anthropology of India, Pakistan and Nepal, New York, Plenum Press, pp. 77-88.

- Shaffer, Jim. 1986. Cultural Development in the Eastern Punjab. In Studies in the Archaeology of India and Pakistan (195-235). Ed. Jerome Jacobson. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Talageri, Shrikant: The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis. 2000. ISBN 81-7742-010-0 ; —Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism. 1993.

- Thapar, Romila. 1966. A History of India: Volume 1 (Paperback). ISBN 0-14-013835-8

- Trautmann, Thomas. The Aryan Debate in India (2005) ISBN 0-19-566908-8

- G Chaubey et al. Peopling of South Asia: investigating the caste-tribe continuum in India Bioessays 29 issue 1 (2007)

See also

- Indo-Aryans, Aryan, Arya, Aryavarta, Indo-Aryan languages

- Rigveda

- Indo-Iranians, Indo-Iranian languages

- BMAC, Andronovo culture

- Mitanni

- Kurgan

External links

- DMOZ listing

- Witzel, Michael: The Home of the Aryans

- Web Index to AIT versus OIT debate

- `What is Aryan Migration Theory ?' by Vishal Agrawal

- Agarwal, Vishal: Is There Vedic Evidence for the Indo-Aryan Immigration to India? (pdf)

- Thapar, Romila: The Aryan question revisited (1999)

- Kazanas, Nicholas homepage Articles by Nicholas Kazanas

- Elst, Koenraad: Update on the Aryan Invasion Theory - K. Elst's Online book, Articles, Book reviews

Archaeology

- Cache of Seal Impressions Discovered in Western India

- Central Asia 2000-1000BC (Metmuseum.org)

- Lal, B.B.: The Homeland of Indo-European Languages and Culture: Some Thoughts By Archaeologist B.B. Lal

- Danino, Michel: The Indus-Sarasvati Civilization and its Bearing on the Aryan Question Article by Michel Danino

- Agrawal, D.P.: The Indus Civilization = Aryans equation: Is it really a Problem? By D.P. Agrawal (pdf)

Genetics

- Genetic Evidence on the origins of Indian Caste Population, Genome Research, 2001

- A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios, PNAS paper, 2006

- Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists, AJHG paper, 2006

Religious and political aspects

]

Categories: