This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Mureungdowon (talk | contribs) at 01:00, 24 April 2023. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:00, 24 April 2023 by Mureungdowon (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) An accepted version of this page, accepted on 24 April 2023, was based on this revision.Overview of anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea

Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea has its roots in historic, cultural, and nationalistic sentiments.

The first recorded anti-Japanese attitudes in Korea were effects of the Japanese pirate raids and the later 1592−98 Japanese invasions of Korea. Sentiments in contemporary society are largely attributed to the Japanese rule in Korea from 1910 to 1945. A survey in 2005 found that 89% of those South Koreans polled said that they "cannot trust Japan." More recently, according to a BBC World Service Poll conducted in 2013, 67% of South Koreans view Japan's influence negatively, and 21% express a positive view. This puts South Korea behind mainland China as the country with the second most negative feelings of Japan in the world.

Historical origins

Japanese invasions of Korea

Main articles: Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), Nose tomb, Mimizuka, and Japanese pottery and porcelain| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2011) |

During this time, the invading Japanese dismembered more than 20,000 noses and ears from Koreans and brought them back to Japan to create nose tombs as war trophies. In addition after the war, Korean artisans including potters were kidnapped by Hideyoshi's order to cultivate Japan's arts and culture. The abducted Korean potters played important roles to be a major factor in establishing new types of pottery such as Satsuma, Arita, and Hagi ware. This would soon cause tension between the two countries; leaving the Koreans feeling that a part of their culture was stolen by Japan during this time.

Effect of Japanese rule in Korea

See also: Korea under Japanese ruleKorea was ruled by the Japanese Empire from 1910 to 1945. Japan's involvement began with the 1876 Treaty of Ganghwa during the Joseon Dynasty of Korea and increased over the following decades with the Gapsin Coup (1882), the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), the assassination of Empress Myeongseong at the hands of Japanese agents in 1895, the establishment of the Korean Empire (1897), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), the Taft–Katsura Agreement (1905), culminating with the 1905 Eulsa Treaty, removing Korean autonomous diplomatic rights, and the 1910 Annexation Treaty (both of which were eventually declared null and void by the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1965).

Japan's cultural assimilation policies

The Japanese annexation of Korea has been mentioned as the case in point of "cultural genocide" by Yuji Ishida, an expert on genocide studies at the University of Tokyo. The Japanese government put into practice the suppression of Korean culture and language in an "attempt to root out all elements of Korean culture from society."

"Focus was heavily and intentionally placed upon the psychological and cultural element in Japan's colonial policy, and the unification strategies adopted in the fields of culture and education were designed to eradicate the individual ethnicity of the Korean race."

"One of the most striking features of Japan's occupation of Korea is the absence of an awareness of Korea as a 'colony', and the absence of an awareness of Koreans as a 'separate ethnicity'. As a result, it is difficult to prove whether or not the leaders of Japan aimed for the eradication of the Korean race."

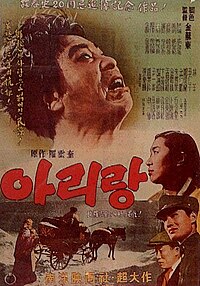

After the annexation of Korea, Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. The Korean language was removed from required school subjects in Korea in 1936. Japan imposed the family name system along with civil law (Sōshi-kaimei) and attendance at Shinto shrines. Koreans were formally forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places. However, many Korean language movies were screened in the Korean peninsula. In addition, Koreans were angry over Japanese alteration and destruction of various Korean monuments including Gyeongbok Palace (경복궁, Gyeongbokgung) and the revision of documents that portrayed the Japanese in a negative light.

Independence movement

See also: Liberalism in South Korea § History, and Korean independence movementOn March 1, 1919, anti-Japanese rule protests were held all across the country to demand independence. About 2 million Koreans actively participated in what is now known as the March 1st Movement. A Declaration of Independence, patterned after the American version, was read by teachers and civic leaders in tens of thousands of villages throughout Korea: "Today marks the declaration of Korean independence. There will be peaceful demonstrations all over Korea. If our meetings are orderly and peaceful, we shall receive the help of President Wilson and the great powers at Versailles, and Korea will be a free nation." Japan repressed the independence movement through military power. In one well attested incident, villagers were herded into the local church which was then set on fire. The official Japanese count of casualties include 553 killed, 1,409 injured, and 12,522 arrested, but the Korean estimates are much higher: over 7,500 killed, about 15,000 injured, and 45,000 arrested.

Comfort women

See also: Japan–South Korea Comfort Women AgreementMany Korean women were kidnapped and coerced by the Japanese authorities into military sex slavery, euphemistically called "comfort women" (위안부, wianbu). Some Japanese historians, such as Yoshiaki Yoshimi, using the diaries and testimonies of military officials as well as official documents from Japan and archives of the Tokyo tribunal, have argued that the Imperial Japanese military was either directly or indirectly involved in coercing, deceiving, luring, and sometimes kidnapping young women throughout Japan's Asian colonies and occupied territories. In the case of recruiting Japanese comfort women(일본군위안소 종업부 등 모집에 관한건) (1938.3.4), the Ministry of Army records that the method of recruiting military "Japanese Military Sexual Slavery" in Japan was "similar to kidnapping" and was often misunderstood by the police as kidnappers.

Park Yu-ha, a Korean professor of Japanese language and literature at Seoul's Sejong University wrote a book titled Comfort Women of the Empire, in which she disputed the numbers of Korean comfort women. She interviewed many survivors and sifted through Japanese military records, and says there's some evidence some of the women were given labor contracts as prostitutes. Her book challenged the view that all of them were rape victims, and says there were Korean middle men, or collaborators, who helped traffic Korean women, leading to the book's censorship in Korea, and to Park being labeled a Japanese apologist and a traitor. She would later tell NPR "Nowadays, people think Japan came and raped and never gave compensation, but that's not totally accurate. I've been a victim of this anti-Japanese sentiment". South Korea's mainstream academic circle, which is critical of her, argues that she provides intellectual justification for Japanese historical revisionism and that her argument should be equated to Holocaust denial.

After declaring in 2015 that the comfort women issue had been resolved "finally and irreversibly", in 2019, the South Korean government dissolved the foundation (the Reconciliation and Healing Foundation) set up for the purpose of providing support for former comfort women to which Japan had contributed 1 billion yen, without consent from the Japanese government. A task force created by Moon Jae-in "criticized the previous administration for not doing more outreach to the surviving comfort women, and making too many concessions to the Japanese side."

Contemporary issues

Including non-Korean race Japanese-born naturalized South Korean liberal scholar Yuji Hosaka and centre-left media Hankyoreh, argue that South Korea's anti-Japanese sentiment has nothing to do with racism. They argue that anti-Japanese and anti-Chinese sentiment in South Korea is mainly anti-imperialism stemming from conflicts related to history, politics and culture, and that race is not the main factor. Many Koreans believe that resistance-nationalism is necessary to counter strong powers such as China and Japan. Unlike Japan, there is no anti-Chinese/anti-Japanese racist hate group in South Korea like Zaitokukai. Korean language is different from English language, and tends to distinguish between "anti-Japan sentiment" (반일) and "hate-of-Japanese racism" (혐일). The former ostracizes Japan in an anti-imperialistic and non-ethnic context, and the latter ostracizes Japan in all contexts, including race/ethnic.

According to a 2022 survey, racism against Japanese in South Korea is only accusations related to historical issues, and rarely discriminated against in everyday life, while racism against Vietnamese and Chinese from communist countries is more pronounced in South Korea.

Effects of sentiments

Society

A 2000 CNN ASIANOW article described popularity of Japanese culture among younger South Koreans as "unsettling" for older South Koreans who remember the occupation by the Japanese.

While some South Koreans expressed hope that former Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama would handle Japanese-South Korean relations in a more agreeable fashion than previous conservative administrations, a small group of protesters in Seoul held an anti-Japanese rally on October 8, 2009, prior to his arrival. The protests called for Japanese apologies for World War II incidents and included destruction of a Japanese flag.

Due to the anti-imperialist sentiment of the South Korean people, South Korean TV dramas often portray Chinese and Japanese people negatively.

National relations

Yasuhiro Nakasone discontinued visits to Yasukuni Shrine due to the People's Republic of China's requests in 1986. However, former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi resumed visits to Yasukuni Shrine on August 13, 2001. He visited the shrine six times as Prime Minister, stating that he was "paying homage to the servicemen who died for defense of Japan." These visits drew strong condemnation and protests from Japan's neighbors, mainly China. As a result, China and South Korea refused to meet with Koizumi, and there were no mutual visits between Chinese and Japanese leaders after October 2001 and between South Korean and Japanese leaders after June 2005. Former President of South Korea Roh Moo-hyun suspended all summit talks between South Korea and Japan.

Education

A large number of anti-Japanese images made by school children from Gyeyang Middle School, many of which depicting acts of violence against Japan, were displayed in Gyulhyeon station as part of a school art project. A number of the drawings depict the Japanese flag being burned, bombed, and stepped on, in others the Japanese islands are getting bombed and destroyed by a volcano from Korea. One depicts the Japanese anime/manga character Sailor Moon holding up the South Korean flag with a quote bubble saying roughly "Dokdo is Korean land".

Politics

Political anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korean politics is more pronounced in the liberal-to-progressive camp than in the conservative camp. Condemning cooperation with Japan has long been the linchpin of South Korea’s liberal-to-progressive agenda from both a human rights and decolonization perspective. This view of South Korean liberal-to-progressives, which is bound to conflict with the view of Japanese conservatives who support historical revisionism based on Japanese nationalism. Western experts say that the conflict between the two countries intensifies the most when a conservative (mainly LDP) regime is established in Japan and a liberal (mainly DPK) regime is established in South Korea.

In South Korea, "anti-Japanism" (반일주의) is considered 'political correctness' in a post-colonistic sense rather than 'racism'. "Anti-Japan" is perceived as moral and progress in South Korea, and "pro-Japan" tends to be considered a political 'far-right' (극우) in the sense of ignoring victims of past colonial times. South Korean liberals tend to be more pro-immigrant and more sensitive to racism (on all issues except the Japanese) than conservatives, but they tend not to be in matters related to racism to Japanese people. Some South Korean liberals and progressives use the term "Tochak Waegu" (토착왜구), "Japanese far-right" (일본 극우), or "far-right pro-Japanese" (극우적 친일) to criticize some conservatives. The reason why anti-Japanese activities are considered political correctness in South Korea is to establish historical justice for the victims and their descendants.

The United States's ambassador to South Korea, Harry B. Harris Jr., who is of Japanese descent, has been criticized in the South Korean media for having a moustache, which his detractors say resembles those of the several leaders of the Empire of Japan. A CNN article written by Joshua Berlinger suggested that given Harris's ancestry, the criticism of his mustache may be due to racism. South Korean liberal media point out that Harry B. Harris Jr. had similar words and actions to the right-wing of Japan. On November 30, 2019, Harris verbally abused, saying, "There are many Jongbuk leftists around the president of Moon" (문 대통령 종북좌파에 둘러싸여 있다는데). On January 16, 2020, he was criticized by the Democratic Party of Korea for "interference in internal affairs" (내정 간섭) for saying that U.S. consultation was needed on tourism to North Korea. South Korean liberal media believe the attack on his beard is not racist because he attacked the South Korea's "national sovereignty" (주권) using rhetoric like "Japanese colonial governor" (일본 총독).

South Korea's centre-right newspaper JoongAng Ilbo published an article on August 23, 2020, positively evaluating the '1974 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries bombing' carried out by Japan's "anti-Japaneseist" far-left terrorist group EAAJAF. The article described the incident as "They tried to expose Japan's 'perpetrator state' identity and fight it with violence" ('가해국' 일본의 정체성을 들춰내며 폭력으로 싸우려 했던). This article does not criticize terrorism in the EAAJAF. Mitsubishi Heavy has a negative perception in South Korea because he cooperated in Japanese war crimes during World War II. Koreans were also mobilized for forced labor for the benefit of Mitsubishi Heavy and other Japanese companies.

When Shinzo Abe was assassinated, many South Korean liberal or progressive people mocked his death. Many South Koreans have a strong antipathy to Shinzo Abe's ultranationalist view and historical negationism of Japanese war crimes.

Chinilpa

Main article: ChinilpaIn South Korea, collaborators to the Japanese occupation government, called Chinilpa (친일파), are generally recognized as national traitors. The South Korean National Assembly passed the special law to redeem pro-Japanese collaborators' property on December 8, 2005, and the law was enacted on December 29, 2005. In 2006, the National Assembly of South Korea formed a Committee for the Inspection of Property of Japan Collaborators. The aim was to reclaim property inappropriately gained by cooperation with the Japanese government during colonialization. The project was expected to satisfy Koreans' demands that property acquired by collaborators under the Japanese colonial authorities be returned. Chinilpa is often identified with "Nazi collaborators" (나치 협력자) or "fascists" (파시스트).

South Korean right-wing conservative politicians and elites, where many are the children and grandchildren of Chinilpa. This gives moral legitimacy to the anti-Japanese sentiment of South Korean liberal-to-progressives as an area of political correctness.

2019 boycott of Japanese products in South Korea

In August 2019, Seoul, the capital of South Korea, had planned to install more than 1,000 anti-Japan banners across the city in a move to support the country's ongoing boycott against Japanese products. At that time, liberal Democratic Party of Korea, which was negative about 'Japanese imperialism', was the ruling party in Seoul city. The banners featured the word “NO,” in Korean, with the red circle of the Japanese flag representing the “O”. The banners also contained the phrases “I won’t go to Japan” and “I won’t buy Japanese products.” However, after 50 banners were installed, the city had to reverse course and apologize amid conservative criticism that the campaign would further strain the relationship between South Korea and Japan.

Feminist movements

Feminist movement in South Korea also often has anti-Japanese sentiment. This was naturally formed by war crimes committed by the Japanese Empire during the past World War II, such as Korean Women's Volunteer Labour Corps, Comfort Women, etc. South Korea's far-right (anti-feminist) conservative-biased media accuse feminist schoolteachers of anti-Japanese education.

However, South Korean feminists actively interact with Japanese feminists. Japanese society antagonizes its feminist movement by calling it "anti-Jepanese" because South Korean and Japanese feminist movements is related to the issue of war crimes against Korean women committed by Japan in the past.

Political correctness and cancel culture

Politically incorrect in Japanese creations can often be canceled in South Korea. However, much of South Korea's political correctness and cancel culture is not irrelevant to anti-Japan sentiment, as it often appears in anti-imperialist sentiment, mostly related to the Japanese, rather than comprehensive concepts like the U.S.

Japan's "Taisho Romance" (Template:Lang-ja, Template:Lang-ko) has been the subject of great controversy in South Korea. Since Korea was a Japanese colony during the Taisho period, many South Koreans do not appreciate the positive treatment of this period in Japanese creations such as Manga and Anime. This can often be subject to boycotts.

"Right-wing bias controversy" (Template:Lang-ja, Template:Lang-ko) is a term that can be used in many fields, meaning controversy over Japanese nationalist tendencies or hate-of-Korean "kenkan" racist tendencies in Japanese entertainers, Japanese creations, and Japanese media. It is also often subject to social criticism and canceled in South Korea.

Unification church issues

Spiritual sales, and the assassination of Shinzo Abe

The Unification Church (UC) is a new religion founded by Sun Myung Moon in Seoul in 1954; its missionaries began activities in Japan in 1958. The UC is accused of engaging in what is locally termed as "spiritual sales" (Template:Lang-ja). The UC would tell their targets that they must donate to the church or they, or their relatives, either living or deceased, would be damned to hell. The UC demands their targets donate all of their savings, as well as selling their properties or applying for loans to make the payments. According to the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales, an anti-cult lawyers group, the total confirmed financial damages linked to the UC during the 35 years through 2021 have surpassed 123.7 billion yen (899.2 million USD).

According to the Japanese lawyer Masaki Kito, who also represents the anti-cult lawyers group, the UC specifically targets the Japanese people because of the invasion of Korea by Japan. The UC would tell their target that "in order to atone for that sin, you must make contributions to Korea".

UC's practice of spiritual sales was widely reported by Japanese media as the primary cause which drove a gunman, whose mother went bankrupt due to her exorbitant donations for the church, to assassinate former prime minister Shinzo Abe on 8 July 2022.

Pro-Japanese controversy in Unification Church

Japanese liberals, including Yoshifu Arita, criticized UC as an "extreme Korean ultranationalist". Ironically, South Korean liberals perceive UC as a far-right Chinilpa (or 'pro-Japanese') religion. Long before Abe's assassination, South Korean liberals and mainstream Korean Christians often denounced the UC as a far-right pro-Japanese group, as it is deeply linked to Japanese conservatives. Since UC is closely related to Japanese right-wing conservatives, including the "kenkan" LDP, South Korean liberals do not admit that UC is a ' Korean nationalist'. South Korean liberals and Korean nationalists in South Korea are hostile to Japanese conservatism and Japanese nationalism. According to Yoshifu Arita, the Japanese politicians linked to UC are ironically conservative politicians who promote anti-Korean "kenkan" racism, including Shinzo Abe. UC organizations have been linked to anti-communist right-wing conservatives in Japan and South Korea.

There is a controversy in South Korea that UC believers and children defend Japanese historical revisionism. In contrast, in Japan, the main figures of the Unification Church often made remarks demonizing Japan. The reason why the Unification Church promotes pro-Japanese sentiment in South Korea and pro-South Korean sentiment in Japan is that they are working on a project to create a "Japan-South Korea Undersea Tunnel". (However, after Abe's assassination, the project was virtually suspended.)

See also

- Anti-Korean sentiment in Japan

- Anti-Japaneseism

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in China

- Japan–Korea disputes

- Boycotts of Japanese products

- Japan–South Korea trade dispute

- Anti-imperialism

- Censorship of Japanese media in South Korea

Notes

- Template:Lang-ko; Hanja: 反日感 情, Banil gamjeong

- South Korean liberals argue that "anti-Japanese" (반일) by Koreans does not lead to hate speech or violence against the Japanese, and that most of them are justifiable criticisms of 'not showing a proper apology for the history of colonial rule and aggression committed in the past'. In contrast, South Korean liberals point out that "Hate of Korea" (혐한) is racism based on colonialist perception. They argue that "anti-Japanese" are not racism because Korea has never colonized Japan, tried to take away its language and culture, and has never carried out genocide.

- In order to avoid economic losses from trade disputes with Japan in South Korea, conservative politicians in South Korea who do not demand proper compensation in matters involving colonial and war crime victims, or who do not actively protest Japanese historical revisionism, are often criticized as "far-right pro-Japanese", "Chinilpa", "Sadaejuui" and "Tochak Waegu" by South Korean liberals and progressives.

- Many American liberals criticize Donald Trump as a far-right neo-fascist, but Shinzo Abe analyzes that he is not a far-right neo-fascist at the level of Donald Trump. However, while many South Korean liberals often do not view Donald Trump as "far-right" because he supported the Sunshine Policy and human rights of comfort women victims, but almost all South Korean liberals accuse Shinzo Abe of being "far-right", " fascist" or "ultranationalist".

References

- "History Today: The educational archive of articles, news and study aids for teachers, students and enthusiasts - History Today - History Today - Top menu - Magazine Online - Archives (1980-2007)". 2007-09-26. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Cooney, Kevin J.; Scarbrough, Alex (2008). "Japan and South Korea: Can These Two Nations Work Together?". Asian Affairs. 35 (3): 173–192. doi:10.3200/AAFS.35.3.173-192. ISSN 0092-7678. JSTOR 30172693. S2CID 153613926.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-10. Retrieved 2014-09-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Sansom, George; Sir Sansom; George Bailey (1961). A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford studies in the civilizations of eastern Asia. Stanford University Press. pp. 360. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

Visitors to Kyoto used to be shown the Minizuka or Ear Tomb, which contained, it was said, the ears of those 38,000, sliced off, suitably pickled, and sent to Kyoto as evidence of victory.

- Saikaku, Ihara; Gordon Schalow, Paul (1990). The Great Mirror of Male Love. Stanford Nuclear Age Series. Stanford University Press. pp. 324. ISBN 0-8047-1895-4.

The Great Mirror of Male Love. "Mimizuka, meaning "ear tomb", was the place Toyotomi Hideyoshi buried the ears taken as proof of enemy dead during his brutal invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1997.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (September 14, 1997), "Japan, Korea and 1597: A Year That Lives in Infamy", The New York Times, retrieved 2008-09-22

- Purple Tigress (August 11, 2005). "Review: Brighter than Gold - A Japanese Ceramic Tradition Formed by Foreign Aesthetics". BC Culture. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- "Muromachi period, 1392-1573". Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2002. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

1596 Toyotomi Hideyoshi invades Korea for the second time. In addition to brutal killing and widespread destruction, large numbers of Korean craftsmen are abducted and transported to Japan. Skillful Korean potters play a crucial role in establishing such new pottery types as Satsuma, Arita, and Hagi ware in Japan. The invasion ends with the sudden death of Hideyoshi.

- John Stewart Bowman (2002). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 170p. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- See Russian eyewitness account of surrounding circumstances at "Korea Web – Market Hero Review 2019". Archived from the original on 2012-10-12. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- ^ "'Cultural Genocide' and the Japanese Occupation of Korea". Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- (in Japanese) Instruction concerning the Korean education Decree No.229 (1911) 朝鮮教育令(明治44年勅令第229号), Nakano Bunko. Archived 2009-10-25.

- Cumings, Bruce G. "The Rise of Korean Nationalism and Communism". A Country Study: North Korea. Library of Congress. Call number DS932 .N662 1994.

- "KimSoft ⋆ Korea Web Weekly, actualidad y más". Archived from the original on 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- The Samil (March First) Independence Movement Archived 2007-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Dr. James H. Grayson, "Christianity and State Shinto in Colonial Korea: A Clash of Nationalisms and Religious Beliefs" Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine DISKUS Vol.1 No.2 (1993) pp.13-30.

- Bruce Cummings, Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History, W.W. Norton & Company, 1997, New York, p. 231, ISBN 0-393-31681-5.

- "WCCW Film Festival Nov 9 - 11 2018".

- Yoshimi Yoshiaki, 従軍慰安婦 (Comfort Women). Translated by Suzanne O'Brien. Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-231-12032-X

- Min, Pyong Gap (2003). "Korean "Comfort Women": The Intersection of Colonial Power, Gender, and Class". Gender and Society. 17 (6): 938–957. doi:10.1177/0891243203257584. ISSN 0891-2432. JSTOR 3594678. S2CID 144116925.

- an adjutant to the Japanese Army (1938), In the case of recruiting Japanese comfort women

- Frayer, Lauren (May 30, 2017). "Not All South Koreans Satisfied With Japan's Apology To 'Comfort Women'". NPR.

- Shin Dong-kyu ed. (2016). The logic of Holocaust Negationism and Comport Women of the Empire of PARK Yuha: Challenge against Collective memory and emotion through unhistorical narratives. Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information.

- "South Korea formally closes Japan-funded 'comfort women' foundation". The Japan Times. 2019-07-05. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- Stangarone, Troy (2020-12-08). "The Comfort Women Agreement 5 Years On". Korea Economic Institute of America. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- "'新친일파·쿨재팬'은 어떻게 만들어지나". 31 July 2019.

- ""일본 우파 논리를 그대로 가져온 21세기 신친일파"". 8 April 2020.

- ^ "일본의 혐한, 한국의 반일". The Hankyoreh. 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- "광화문에서 성조기와 이스라엘기를 흔드는 이들에게". 프레시안. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- "반일(反日)과 혐일(嫌日) 사이". 이데일리. 2019-07-24. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- "혐중 정서, 혐일 앞섰다… 가장 차별 느낀 건 베트남인" [Lee Jae-myung said, "Japan, an aggressive country, should have been divided, not Korea..."]. 서울신문. 17 August 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

눈에 띄는 건 중국인과 일본인이 느낀 차별 정도가 역전됐다는 점이다. 첫 3년(2011~2013년)간 일본인 중 3점 이상의 심한 차별을 경험한 응답자는 10.7%였지만, 이후 꾸준히 감소해 최근 3년간은 0%였다. 약한 혐오차별은 당했지만 예전처럼 극심한 차별에서는 벗어났다는 얘기다. 호사카 유지 세종대 대우교수는 "한국에서 반일 감정은 보통 일본이라는 국가와 정부, 과거 역사 등을 겨냥해 표출될 뿐 일상생활에서는 잘 표현하지 않는다"고 말했다.

- "Japanese pop culture invades South Korea." CNN.

- "SOUTH KOREA: Anti-Japanese rally in Seoul ahead of Japanese prime minister's visit" Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, ITN Source, October 9, 2009.

- Oh In-gyu ed. (2016). Hallyu Consumption through Overcoming Nationalism - Japanese and Chinese Reaction to Anti - Japanese and Anti - Chinese Content within Hallyu TV Dramas. Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information.

- (in Japanese) "小泉総理インタビュー 平成18年8月15日" Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine (Official interview of Koizumi Junichiro on August 15, 2006), Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, August 15, 2006.

- Don Kirk, "Koizumi Move Sparks Anger In China and South Korea" International Herald Tribune, August 14, 2001.

- and (in Korean) "노무현 대통령, “고이즈미 일본총리가 신사참배 중단하지 않으면 정상회담도 없을 것” (영문기사 첨부)" Archived May 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, 03/17/2006.

- "Children's drawings in the subway!, How cute" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine , Jun 13 2005, "More children's drawings displayed in the subway., The second time is just like the first" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Jun 18 2005, A passing moment in the life of Gord.

- (in Korean) "외국인들 “한국인 반일 감정 지나치다”" Archived December 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Daum, 2005-10-1.

- James Card "A chronicle of Korea-Japan 'friendship'", Asia Times, Dec 23, 2005, "The most disturbing images of the year were drawings on exhibit at Gyulhyeon Station on the Incheon subway line..."

- ^ "Abe's Death, and Korea's Japanophobia". KOREA EXPOSÉ. 13 July 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- "How Biden Can Navigate a New Era in South Korean Politics". The Diplomat. 15 January 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Buruma, Ian (12 August 2019). "Opinion | Where the Cold War Never Ended". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Is America, like Japan, getting 'Korea fatigue'?". The interpreter. 19 May 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

But 'anti-Japanism' is now a form of political correctness in South Korea; public officials dare not bend (particularly on the right, where many are the children and grandchildren of collaborators).

- "정진석 "일본, 조선과 전쟁한 적 없다"… '극우적 친일 DNA' 발언". 굿모닝충청. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- "김상수 "친일찬양금지법 입법하라..언제까지 시민들이 나서서 거리에서 싸우게 만드는가?"". 뉴스프리존. 11 October 2022.

- "중국 유학생들, '한국인이 중국 배척하고 무시'" (in Korean). 한겨레. 2008-08-27.

- "이주민 10명 중 7명 "한국에 인종차별 있다"" (in Korean). 경향신문. 2020-03-19.

- "일본의 혐한, 한국의 반일" (in Korean). The Hankyoreh. 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- "램지어와 '일본 극우' 대변하는 그들, 박유하·류석춘·이영훈·안병직 등은 "극우 아닌, 친일매국노일 뿐" (feat. '위안부' 2차 가해)". 뉴스프리존. 19 February 2021.

- "정진석 "일본, 조선과 전쟁한 적 없다"… '극우적 친일 DNA' 발언". 굿모닝충청. 11 October 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ""윤 정부, 국익 위해 독배 마셨다"는 박형준에 "시장 자격 없다"". 한겨레. 9 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

부산 160여개 단체가 모여 만든 '강제징용피해자 양금덕할머니 부산시민 평화훈장 추진위원회'는 9일 부산시청 들머리에서 기자회견을 열어 "친일·사대·매국 망언을 내뱉은 박형준은 부산시장 자격이 없다"고 성토했다.

- Berlinger, Joshua (17 January 2020). "Why South Koreans are flipping out over a US ambassador's mustache". CNN. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "해리스 주한 美대사 "문 대통령 종북좌파에 둘러싸여 있다는데…"". 한국경제 (in Korean). 2019-12-01.

- "해리스 대사 발언에, 여권 "내정간섭"…야권 "한미동맹 할 때"". KBS NEWS (in Korean). 2020-01-17.

- "해리스만 모르는 척하는 '콧수염' 논란의 본질". 미디어오늘 (in Korean). 2020-01-19.

- "미쓰비시 등 8곳 연쇄폭파···日 공격한 그들은 일본인이었다". 중앙일보 (in Korean). 23 August 2020. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023.

- "Yoon visits Japan, seeking to restore ties amid N Korea threat". Al Jazeera. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023.

But many in South Korea did not consider Japan's remorse as sufficiently sincere, especially as the ultranationalist former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was assassinated last year, and his allies sought to whitewash Japan's colonial abuses, even suggesting there was no evidence to indicate Japanese authorities coerced Korean women into sexual slavery.

- "트럼프와 포옹한 이용수 할머니, 일본에 일침 "참견 마라"" [Elderly lady Lee Yong-soo hugged Trump. ... She spoke strongly to the Japan's "Don't interfere"]. 중앙일보. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- "문정인 "바이든이 미 대통령 되면 북한 문제 풀기 어려워"" [Moon Chung-in said, "If Biden becomes the U.S. president, it will be difficult to solve the North Korean problem".]. 동아일보. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- "아베는 철저히 '아름다운 일본'을 고수했다". 경향신문. 25 July 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

한국에서 아베 전 총리는 흔히 극우 정치인 내지 일본 극우 세력의 핵심 인물로 여겨진다. 국제사회의 평가는 다르다. 아베 전 총리의 부고를 전하는 서구권 외신 기사 대부분은 "일본 전시 역사에 대한 모호한 태도와 안보에 대한 강경한 자세로 한국과의 갈등을 초래했다"(워싱턴포스트)고 짚으면서도 그를 '극우'로 여기는 경우는 많지 않다.

[In South Korea, Abe is mostly considered a "far-right politician" or a "key figure in Japanese far-right forces". However, the international community's assessment is different. Most Western foreign articles that convey Abe's obituary pointed out that "the ambiguous attitude toward Japanese war crimes history and hawkish attitude toward security caused conflict with South Korea" (Washington Post), but it is not common to regard him as a "far right".] - "Assets of Japan Collaborators to Be Seized", The Korea Times, August 13, 2006.

- "김원웅 "북한 3대세습, 종북좌파 아닌 친일파 이승만·박정희 때문"". 시사오늘. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "대한민국의 '독버섯'". 경기일보. 15 November 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "부끄러운 역사 친일 '미완의 청산'". 경향신문. 15 August 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "반민특위에서 풀려난 친일 헌병, 김주열을 쐈다". 미디어오늘. 11 September 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Kang, Tae-jun. "Voices Grow in South Korea to Oppose Anti-Japan Movement". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- "'NO JAPAN' 배너 반나절 만에 철거…"불매운동 정신 훼손"". KBS 뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- "일제 식민지만행 규탄운동을 벌이는 여성단체들". Korea Democracy Foundation. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ""베를린 소녀상 철거하라고? 더 배워!… 베를린 시민이 지킨다"". 여성신문. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- " 전교조의 '민낯'을 보려거든, 눈을 들어 '인헌고'를 보아라". 스페셜경제SE. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023.

- "'위안부' 문제 연구에 반일(反日) 낙인은 부당해". 일다. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "프로젝트 세카이 '다이쇼 로망' 논란…왜 유저들은 환불에 나섰나". 소비자경제. 7 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "히라노 쇼, 음습한 우익 혐한 발언 논란…첫 내한에 "來日"". 뉴스엔. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Japan lawyers accuse Unification Church of entrapping many families following Abe killing", Japan Times, 2022-07-30, retrieved 2022-08-02

- "EDITORIAL: Politicians' ties to Unification Church should be made public". Asahi Shimbun. 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- "紀藤弁護士、旧統一教会への献金に日韓格差指摘 戦前の「罪」理由に". daily.co.jp (in Japanese). 2022-07-15. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ^ "일본 아리타 요시후 前 의원, "日 통일교 종교법인 100% 해산 될 것"". 노컷뉴스. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "'新친일' 통일교와 日자민당 정권 40년 유착.."자민당 의원 180명과 관계"". 노컷뉴스. 5 September 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ "친일 "통일교" 청년들, 신촌 대학로서 "일본사랑" 외쳐". 종교와 진리. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "아베 사후 다시 부각된 통일교와 한·일 우익 네트워크". 시사IN. 2 August 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "日 언론 "통일교, 한일해저터널 지으려고 14만평 규모 토지매입"". 아시아경제. 13 January 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.