This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Hawkeye7 (talk | contribs) at 21:00, 26 August 2023 (→By sea and air transport: Corrected). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:00, 26 August 2023 by Hawkeye7 (talk | contribs) (→By sea and air transport: Corrected)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) War campaign in WWII For the 2019 Civil Aviation Authority-initiated operation named "Operation Matterhorn", see Thomas Cook Group § 2019:Final year and collapse.

| Operation Matterhorn | |

|---|---|

| Part of the China Burma India Theater of World War II | |

B-29 bomber bases in China and the main targets they attacked in East Asia during Operation Matterhorn B-29 bomber bases in China and the main targets they attacked in East Asia during Operation Matterhorn | |

| Location | East Asia and Southeast Asia |

| Commanded by | |

| Date | 1944–1945 |

| Executed by | XX Bomber Command |

| Bombing of South East Asia, 1944–1945 | |

|---|---|

Operation Matterhorn was a military operation of the United States Army Air Forces in World War II for the strategic bombing of Japanese forces by Boeing B-29 Superfortresses based in India and China. Targets included industrial facilities in Japan and Japanese bases in China and Southeast Asia. The name comes from the Matterhorn, a mountain traditionally considered particularly difficult to climb.

Background

B-29 Superfortress

Main article: Boeing B-29 SuperfortressOn 29 January 1940, the United States Army Air Corps issued a request to five major aircraft manufacturers to submit designs for a four-engine bomber with a range of 2,000 miles (3,200 km). These designs were evaluated, and on 6 September orders were placed for two experimental models each from Boeing and Consolidated Aircraft, which became the Boeing B-29 Superfortress and the Consolidated B-32 Dominator. These were known as very long range (VLR) bombers. On 17 May 1941, Boeing was ordered to commence the manufacture of the B-29 when ready.

Boeing devoted its plants in Renton, Washington and Wichita, Kansas to B-29 production; assemblies would later also be built by the Bell Aircraft Corporation in Marietta, Georgia, and the Glenn L. Martin Company in Omaha, Nebraska. A major recruiting and training program was required. Many of the workers were recruited from the surrounding areas, and had no experience in aircraft manufacturing. As they became more skilled, the man-hours required to build a B-29 was reduced from 150,000 to 20,000. The $3 billion cost of design and production (equivalent to $51 billion today), far exceeded the $1.9 billion cost of the Manhattan Project, made the B-29 program the most expensive of the war.

With its 141-foot (43 m) wingspan, the B-29 was one of the largest aircraft of World War II. It sported state-of-the-art technology, which included a pressurized cabin, dual-wheel tricycle landing gear, and an analog electromechanical computer-controlled fire-control system that allowed the four gunners to direct five remote machine gun turrets, each with twin Browning .50 caliber machine guns; the rear turret also had a 20-mm cannon. It was powered by four 18-cylinder, 2,200-horsepower-hour (1,600 kWh) Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engines, each with two turbochargers.

The cumulative effect of so many advanced features was more than the usual number of problems and defects associated with a new aircraft. This was compounded by efforts to fast track its introduction into service. These included engine malfunctions, jammed gears and dead power plants. The engines in particular had a large number of defects. The front and rear rows of the engine cylinders were located too close together for efficient cooling; there was insufficient lubrication of the upper cylinders; the reduction drive was prone to failure; and the carburetor produced an inefficient fuel mixture distribution. All of these factors contributed to engine overheating, which sometimes resulted in fires owing to an extensive use of magnesium. In spite of 2,000 engineering changes, the engines remained susceptible to overheating. The first prototype XB-29 made its maiden flight on 21 September 1942, but the second crashed on 18 February 1943 after an engine caught fire, killing Boeing test pilot Edmund T. Allen, his ten-man crew, twenty people on the ground, and a firefighter who died fighting the resultant blaze.

Strategy

Ostensibly, the B-29 was intended to defend the Western Hemisphere against encroachment by a hostile foreign power, but as early as September 1939, Colonel Carl Spaatz had suggested that it might be used to bomb Japan from bases in Siberia, Luzon or the Aleutian Islands. The Air Corps' first war plan, AWPD-1, issued in September 1941, called for B-29s to bomb Germany from bases in Great Britain and Egypt by 1944. Early war plans did not contemplate bombing Japan until after the war against Germany was won. The idea of basing the Superfortresses in China first surfaced at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. In March, the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff, Major General Laurence S. Kuter, initiated a detailed study of the possibility of using VLR bombers based in China. No other bases within range of Japan were expected to be in Allied hands in 1944.

Support for the effort would have to come through the port of Calcutta, which was estimated to be able to handle the additional 596,000 short tons (541,000 t) per month. From there, supplies would be flown to China in Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers converted to Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express transport aircraft. About 200 would be required to support each VLR bomber group, with 2,000 C-87s in operation by October 1944 and 4,000 by May 1945. It was estimated that five missions per group per month could be flown, with 168 group-months being sufficient to destroy all targets in Japan within twelve months.

The staff of the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) were invited to comment, and they opined that the plan was too optimistic about the logistical challenges involved. On request, the CBI Theater commander, Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell submitted an alternative plan drafted by his air commander, Major General George E. Stratemeyer, codenamed "Twilight", that called for more time, a smaller effort, and reduced logistical support. Under this plan, the bombers would be based in the Calcutta area and only staged through Chinese bases for missions. Keeping the ground crews in India would reduce the logistical footprint in China. Stilwell cautioned that the likely Japanese response to any success by the bombers would be a ground offensive to capture the airfields. It was estimated that the first raids on Japan could be mounted as early as April 1944.

In April 1943, the commander of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), General Henry H. Arnold, set up a special B-29 project under Brigadier General Kenneth B. Wolfe. Wolfe became responsible for preparing, organizing and training B-29 units for combat. By September, he had prepared a plan for operations based on Twilight called "Matterhorn"; soon after the Twilight plan was renamed "Drake". The difference between Matterhorn and Drake was that under Matterhorn the B-29s would stage through Chengtu in Szechwan province in western China, whereas under Drake they would stage through Kweilin in eastern China. Moving the B-29 bases further back from the front lines allowed the ground defense to be dispensed with, and the air defenses scaled back to two fighter groups that would be assigned to Major General Claire Chennault's China-based Fourteenth Air Force. Supplies would be stockpiled in China by the B-29s themselves, assisted by the B-24s of Fourteenth Air Force's 308th Bombardment Group. Arnold approved the plan on 12 October.

On 10 November 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a massage to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, asking him to render assistance with the construction of bases in India and one to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek asking him to provide labor and materials for the construction of five advanced bases in China, which the United States would pay for under Reverse Lend-Lease. Although Drake still had its advocates, Matterhorn was formally approved by Roosevelt and Churchill at the Sextant Conference in Cairo on 7 December.

The British and American Combined Chiefs of Staff had authorized a Central Pacific drive that included the capture of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, Truk, Palau and the Mariana Islands. but it was not considered likely that they would be available before 1945. The air staff planners began incorporating the Marianas into their plans as a potential base for the B-29s in September 1943. This was formally approved at Sextant. By January 1944, there was consideration of advancing the Central Pacific timetable by bypassing Truk and heading directly for Palau after the capture of the Marshalls, but senior army and navy officers in the Pacific doubted the utility of basing B-29s in the Marianas due to the limited harbor facilities there.

A study by the Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) assessed the Mariana Islands as the best location for the deployment of the B-29s, but in view of the fact that they would not be captured until later in the year, recommended that the first B-29 groups be deployed to the Southwest Pacific Area to attack the petroleum refineries in the Netherlands East Indies or to India and China to attack industrial targets in Japan. The timetable for the Central Pacific advance was revised in March 1944: Truk was to be bypassed and the Palau operation was postponed until 15 September, after the capture of the southern Mariana Islands, which was now scheduled to commence on 15 June 1944. The new timetable was approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 12 March.

Target selection

In March 1943, Arnold had asked the Committee of Operations Analysts (COA) to prepare an analysis of strategic targets in Japan whose destruction might affect the course of the war. Moat of Japan's war industries lay within the 1,500-mile (2,400 km) range of a B-29 with a ten-ton bomb load. The COA had been created in December 1942, and its membership included officers from the Army and Navy, along with distinguished civilians consultants such as Edward M. Earle, Thomas W. Lamont, Clark H. Minor and Elihu Root Jr. In a report delivered on 11 November 1943, they identified six preferred economic targets: merchant shipping, steel production, urban industrial areas, aircraft plants, ball bearings, and electronics.

Particular vulnerable were the ball bearing industry, which relied on six major plants, and the steel industry, which was dependent on a small number of coke plants located on Kyushu and in Manchuria and Korea—all within range of B-29s based at Chengtu. The JWPC also considered targeting, but favored shipping and the oil industry, which could more easily be attacked from bases in Australia. The staff of the USAAF accepted the importance of targeting shipping, but it was not what the B-29 was designed for. As for the oil industry, the oil refineries in the Dutch East Indies, primarily the ones at Palembang, could be attacked by B-29s based in India, staging through Ceylon. The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the Matterhorn plan on 10 April 1944, but cut the force to just one wing of four groups. In recognition of the accelerated schedule for the capture of the Marianas, the second B-29 wing would be sent there instead, or to Australia if bases in the Marianas were not yet ready.

Command and organization

To control the B-29s, the 58th Bombardment Wing was activated at Marietta Army Air Field, near Bell's B-29 plant, on 1 June 1943, and Wolfe had assumed command on 21 June. Although he had an experience in engineering and development in the United States and the Philippines, and an excellent knowledge of the B-29, he had no upper echelon command or operational experience. He did however have a free hand in selecting officers for his organization. Many came from his former command at Wright Field, Ohio, including the leading expert on the B-29, Colonel Leonard F. Harman, who became his deputy. For his assistant chief of staff for operations (A-3), he secured Brigadier General LaVerne G. Saunders, who had been awarded the Navy Cross while in command of the 11th Bombardment Group during the Guadalcanal campaign.

The Second Air Force provided four airfields for training in the vicinity of Salina, Kansas, not far from Boeing's Wichita plant where most of the early model B-29s were made, and the 58th Bombardment Wing moved its headquarters to Smoky Hill Army Air Field near Salina on 15 September. The wing was initially under the direct control of USAAF headquarters, but on 11 October it was assigned to Second Air Force. The XX Bomber Command was activated in Salina, on 27 November 1943, with Wolfe as its commander, and Harman became the commander of the 58th Bombardment Wing.

| Group | Commander | Location |

| 40th Bombardment Group | Colonel Lewis R. Parker | Pratt Army Air Field, Pratt, Kansas |

| 444th Bombardment Group | Colonel Alva L. Harvey | Great Bend Army Air Field, Great Bend, Kansas |

| 462nd Bombardment Group | Colonel Richard H. Carmichael | Walker Army Air Field, Victoria, Kansas |

| 468th Bombardment Group | Colonel Howard E. Engler | Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Smoky Hill, Kansas |

The group commanders had a wealth of experience. The 444th Bombardment Group was led by Colonel Alva L. Harvey, who had been a test pilot for the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and had participated in the first American bombing raid on Berlin. Colonel Richard H. Carmichael led the 462nd Bombardment Group; he had formerly commanded the 19th Bombardment Group in the Southwest Pacific Area, and had led the first B-17 raid on Rabaul in February 1943. Colonel Howard E. Engler commanded the 468th Bombardment Group until August 1944, when he was replaced by Colonel Ted S. Faulkner. The 40th Bombardment Group was commanded by Colonel Lewis R. Parker. He was sent to England to obtain combat experience with the Eighth Air Force and was shot down on his second mission over Germany on 6 March 1944. He was replaced by Harman in April 1944, and Saunders succeeded him as commander of the 58th Bombardment Wing.

Brigadier General Haywood S. Hansell Jr., the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff and the Acting Assistant Chief of the Air Staff for Plans, was appointed the chief of staff of the Twentieth Air Force. As the air member of the JWPC, he was familiar with plans for the deployment and use of the B-29. He held his first staff meeting on 12 April. He was thede facto commander, especially after Arnold suffered a heart attack on 10 May 1944.

The table of organization and equipment for the B-29 groups was authorized on 13 January 1944. Each aircraft had a crew of eleven. Five were officers: the pilot-commander, co-pilot, two navigator-bombardiers, and the flight engineer. The other five were enlisted personnel: an engine mechanic, electrical specialist, power-plant specialist, central fire-control specialist, radio operator and radar operator. Each squadron had seven aircraft, and each of the four groups had four squadrons, so the wing had 112 B-29s. Each B-29 had two crews, so the wing had 3,045 officers, 8 warrant officers and 8,099 enlisted men. With the service and maintenance units and aviation engineers to build the airfields, Wolfe would have about 20,000 men under its command.

XX Bomber Command Order of Battle

- 10th Photo Tech Unit

|

|

|

|

Wolfe and an advanced echelon of his XX Bomber Command staff arrived in New Delhi on 13 January 1944, where he met with Stratemeyer. On 3 February he met with Stilwell at the latter's advanced headquarters in Burma to discuss command arrangements. They agreed that the XX Bomber Command should not come under Chennault's command, nor under that of Stratemeyer, who was answerable Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the commander of South East Asia Command (SEAC). Stilwell therefore issued a directive on 15 February that placed the XX Bomber Command under his own direct command and control.

The command and control of the B-29s was subject to further debate among the Joint Chiefs of Staff. To avoid the B-29s being misused on the battlefields when they would be much more useful against the Japanese home islands, the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, suggested that an air force be created under Arnold's command. Arnold would be responsible for its administration and logistical support, and would control it as the executive agent of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who would determine its deployment and missions. The Joint Chiefs approved the establishment of the Twentieth Air Force on 4 April 1944. This gave the USAAF equal status with the ground and naval forces in Asia and the Pacific for the first time. Stilwell's role as commander of CBI would be restricted to providing logistical support and the defense of the B-29's bases.

Training and preparation

As well as the recruitment of senior staff, Wolfe was authorized to procure twenty-five pilots and twenty-five navigators with experience of long over-water flights in four-engine aircraft. The training of the crews of the 58th Bombardment Wing was rendered difficult by the shortage of B-29s. The first prototype XB-29 was turned over to the USAAF shortly after the 58th Bombardment Wing was formed in June 1943, but the first production B-29 did not arrive until August. In the meantime, crews trained on fifty Martin B-26 Marauders. These were subsequently replaced by B-17s, which were more similar to the B-29. By November 1943 there was still only one B-29 between twelve crews. A month later they had flown an average of just 18½ hours in the B-29, and only 67 commander-pilots were fully qualified on the B-29. In view of this, the number of crews to be trained was reduced to 240, and the date of completion of their training was postponed from 1 February to 1 March.

By February 1944, the entire XX Bomber Command had only flown 9,000 hours in B-29s, and few of these were above 20,000 feet (6,100 m) due to issues with the power plant. Ninety-seven B-29s had been delivered, but two of them had the central fire control system installed, and it had not been fully tested. Because so many modifications had been made while aircraft were being built, it had become standard practice to fly new B-29s direct from the factory to a modification center to be upgraded. The modification centers were overworked, and had limited hangar space, so much of the work had to be done in the open air.

Arnold had hoped that the B-29s would be ready by January 1944, but on 12 October 1943 he had informed Roosevelt:

In connection with the bombing of Japan from China by B-29s, I regret exceedingly to have to inform you that there has been a holdup in production of engines. It looks now as if it will be impossible to get the required number of B-29s together in China to start bombing before the first of March, and with the possibility of not getting them there before the first of April. At this writing I expect to have 150 B-29s in China by March 1st, of which 100 can be used against Japan.

Arnold visited the B-29 plant in Wichita on 11 January 1944 and had his name written on the 175th aircraft, and told the workers that he wanted it delivered by 1 March 1944. They tried their best, but changes disrupted the delivery of key parts. When Arnold visited Pratt Army Air Field on 8 March 1944, he found no B-29s were ready for combat. Arnold designated Brigadier General Bennett E. Meyers, who was traveling with him, as special project cocoordinator, with responsibility for getting the B-29s ready. Meyers chose Colonel Clarence S. Irvine as his deputy. Boeing provided 600 workers, although this slowed work on the production lines. The deficiencies of each aircraft were cataloged and spare parts were obtained. Work was carried out in appalling Kansas winter conditions, with snowstorms and outdoor temperatures between −2 and 20 °F (−19 and −7 °C). By 15 April, 150 aircraft were combat ready.

Base development

India

Airbases

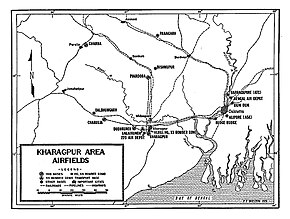

A team headed by Brigadier General Robert C. Oliver, the commander of the CBI Air Service Command, began inspecting potential sites for B-29 bases in August 1943. The B-29's 141-foot (43 m) wing span was considerably wider than the 104-foot (32 m) of the B-17, the next largest aircraft in the inventory, and a fully-laden B-29 weighed about 70 short tons (64 t), nearly twice as much as a B-17. The Twentieth Air Force asked for B-29 runways to be 8,500 feet (2,600 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) wide, nearly twice the area of a 6,000 by 150 feet (1,829 by 46 m) B-17 runway. The plan was to enlarge and improve five existing runways in the flatlands west of Calcutta to bring them up to B-29 standards. Five airfields were selected on 17 November: Bishnupur, Piardoba, Kharagpur, Kalaikunda and Chakulia. Wolfe's advance party from the XX Bomber Command inspected the fields in December and accepted all but Bishnupur, for which Dudhkundi was substituted.

Work was to be carried out by US Army engineer units with imported materials and local labor. Company A of the 653rd Topographic Battalion surveyed the sites to determine how the airfields could be constructed. In order to get the runways operational as soon as possible, the airmen were persuaded to temporarily accept runways 7,500 feet (2,300 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide. Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth E. Madsen was in charge of construction of the air bases; Colonel William C. Kinsolving, a petroleum engineer, had the task of laying two four-inch (100 mm) pipelines to the airfields. They reported to Colonel Thomas Farrell, who headed the CBI Construction Service.

Each air base would require four months' work by an engineer aviation battalion. In order to meet the April deadline, the engineer units should have been in place by December, but they were still in the United States. Stillwell gave them priority for shipping, and they set out on a convoy that sailed on 15 December. Travelling via North Africa, they reached India in February 1944 In the meantime, local contractors and 300 trucks were borrowed from the Engineer-in-chief of the British Eastern Command.

The delay in sending the engineer units threatened to upset the entire Matterhorn timetable. On 16 January 1944, Stilwell diverted the 382nd Engineer Construction Battalion from working on the Ledo Road to working on Kharagpur. It deployed by air, taking over equipment on site. The 853rd Engineer Aviation Battalion arrived in the theater on 1 February and was set to work on Chakulia. Units from the 15 December convoy began arriving in mid-February. The 930th Engineer Regiment was assigned to Kalaikunda, the 1875th Engineer Aviation Battalion to Dudhkundi, the 1877th Engineer Aviation Battalion to Chakulia, and the 879th Engineer Aviation Battalion (Airborne) to Piardoba. As an airborne unit, the 879th was equipped with small, air-portable equipment that was unsuited to airbase work, and was eventually reassigned.

The units worked with borrowed equipment; their unit equipment did not begin to arrive until 15 April, and was not complete until 30 June. Marshall accepted a proposal from Stilwell and Mountbatten to divert units earmarked for amphibious operations in Burma to Matterhorn. Accordingly, he assigned the 1888th Engineer Aviation Battalion. It embarked from the West Coast of the United States in February, and reached India in mid-April. With its arrival, Madsen had 6,000 engineers and 27,000 Indian civilians under contract from India's Central Public Works Department on the job. Religious sensibilities meant that seven different types of rations had to be stocked.

Grading of the runways accounted for more than half of the 1,700,000 cubic yards (1,300,000 m) of the earth moved. New concrete was laid 10 inches (25 cm) tick; existing runways were overlaid with 7 inches (18 cm) of concrete. While sand was obtained from nearby streams and gravel and crushed basalt construction aggregate were obtained locally, Indian cement was in short supply and of inferior quality, so much of the cement was imported from the United States. Concrete was produced locally and spread by hand at all the fields except Kalaikunda, where heavy equipment was used. Chevron- and horseshoe-shaped hardstands were provided, as were paved, rectangular parking areas. To save time and concrete, dispersal areas were omitted.

A variety of buildings were provided. At first the troops lived in tents, but later they were housed in native "basha" huts with earth or concrete floors, bamboo or plaster walls and thatched roofs. Basha huts were also used for administrative and technical buildings, along with U.S. prefabricated plywood structures, some of their Italian counterparts that had been captured in the East African campaign, and British Nissen huts. Workshops and hangers were also provided. Most of the utilities such as electricity and water were installed by U.S. Army engineers. Although reports to USAAF headquarters frequently claimed that work was proceeding on schedule, that schedule was far behind the original plans, and works on the airbases were not completed until September. The decision in April to deploy the send wing of B-29s to the Marianas meant that only four groupds would be deployed to CBI instead of the originally eight, so only the five original airfields were required. Delays in construction at Dudhkundi meant that Charra Airfield had to be used as a temporarily. The B-24 runway there was extended to accommodate the 444th Bombardment Group until Dudhkundi was ready in July. The total cost of constructing the five airbases was estimated at $20 million (equivalent to $346.16 million in 2023).

Pipelines

In addition to the construction or modification of airfields in Bengal, a fuel pipeline to Calcutta and expansion of the port there was proposed. It was estimated that the Matterhorn bases would require 4,736,000 US gallons (17,930,000 L) of fuel in March 1944, 3,536,000 US gallons (13,390,000 L) in April and May, 7,027,000 US gallons (26,600,000 L) in June, 7,077,000 US gallons (26,790,000 L) in July, and 10,608,000 US gallons (40,160,000 L) in August. Each airbase was provided with 1,470,000 US gallons (5,600,000 L) of storage.

A Shell Oil terminal at Budge Budge had a tank farm with a capacity of 500,000 barrels (79,000,000 L), of which 300,000 to 400,000 barrels (48,000,000 to 64,000,000 L) were made available to the U.S. Army. The 700th Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company arrived at Kalaikunda on 3 January 1944, and was given the task of laying a six-inch (15 cm) pipeline from Budge Budge to Kharagpur, a distance of about 60 miles (97 km). The 707th and 708th Engineer Petroleum Distribution Companies arrived a few days later and were assigned the task of laying four-inch (10 cm) pipelines from Kharagpur to Chakulia via Dudhkundi, and from Kharagpur to Piardoba respectively. Each four-inch line was about 50 miles (80 km) long.

Pipelines-

A Navy tanker delivers fuel. Master Sergeant Gerino Terenzi (right) is the section foreman, constantly checking his pumping stations and storage tanks.

A Navy tanker delivers fuel. Master Sergeant Gerino Terenzi (right) is the section foreman, constantly checking his pumping stations and storage tanks.

-

GIs and Indian laborers launch a pontoon on the Hooghly River. Two pontoons lashed together will float pipe to the opposite bank. The main portion of the pipeline will then lie along the river's bottom.

GIs and Indian laborers launch a pontoon on the Hooghly River. Two pontoons lashed together will float pipe to the opposite bank. The main portion of the pipeline will then lie along the river's bottom.

-

At Budge-Budge, pump operator Privates Michael Beyer and Edward Rich work on the 100-octane gasoline pumps.

At Budge-Budge, pump operator Privates Michael Beyer and Edward Rich work on the 100-octane gasoline pumps.

A major obstacle was the Hooghly River, which had a tidal bore of up to 7 feet (2.1 m) and a current that could reach 25 miles (40 km). Heavy pipeline clamps were attached every few joints to hold the pipe in position on the bottom. Laying 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of pipeline across involved scheduling the work for optimal tidal conditions. The pipe was run across with steel cables pulled by large Caterpillar D8 tractors. Three pump stations were established: one at Budge Budge, one at Kharagpur, and one halfway between them. The system began pumping gasoline on 13 March 1944. The 707th operated the system, while the 700th and 708th moved on to other projects.

Due to a shortage of standard pipe, Farell and Kinsolving decided to use thin, light-weight, "invasion-weight" pipe. Pipes were buried to prevent accidental or deliberate damage in densely populated areas. Local labor was required to dig the ditches. "And the contractors' personnel policies, if they can be so dignified, were blends of inefficiency and time-honored skulduggery." The invasion-weight pipe was susceptible to corrosion and leaking 100-octane gasoline could be dangerous. On 26 June 1944, a leak was found where the pipe crossed the Hooghly River near the village of Uluberia. On 1 July a vapor explosion set fire to thatched houses in the village, and seventy-one people died in the ensuing conflagration.

China

Lieutenant Colonel Henry A. Byroade was appointed the project engineer responsible for construction of the B-29 airfields in China. He personally reconoitered the Chengtu area in November 1943, and in his report on 8 December he selected four B-29 airbase sites, Hsiching, Kwanghan, Kiunglai and Pengshan, where existing runways could be strengthened and lengthened to accommodate the B-29s. On 16 March 1944, Byroade assumed the dual role of chief engineer of the 5308th Air Service Area Command and chief engineer of the Fourteenth Air Force.

At the Sextant Conference in Cairo, Roosevelt promised the Chiang that the United States would fully reimburse China for labor and materials expended on Matterhorn. The Chinese estimated that the airbases would cost two to three billion Chinese yuan, around $100 to $150 million (equivalent to $1,400 to $2,100 million in 2023), at least at the official rate of exchange; on the black market an American dollar fetched up to 240 Chinese yuan. Stilwell suspected that half of this sum was in the form of "squeeze" (corruption). "One more example", he wrote in his diary, "of the stupid spirit of concession that proves to them that we are suckers."

A settlement was reached between the Vice Premier of the Republic of China, Kung Hsiang-hsi, and the United States Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr., in June, under which the United States paid China $210 million (equivalent to $2,900 million in 2023), although this included payment for other works in addition to the Chengtu airfields. Arthur N. Young, the American financial advisor the Chinese government was critical of the U.S. Army's profligate spending. The governor of Szechwan set price caps on materials used by contractors, but with limited success. It became necessary to fly banknotes over "the Hump", as the air ferry route to China over the Himalayas was called. Landowners were inadequately compensated for the loss of their land and the peasants who worked it were not compensated at all. Contract workers were paid on a piecework bases, and averaged about 25 Chinese yuan per day. This was barely sufficient to buy food, so many had to be supported by their families. These grievances generated support for the Chinese Communist Party.

Construction work was supervised by Lieutenant Colonel Waldo I. Kenerson. Only fourteen U.S. Army engineers worked on the project. Their role was limited to drafting specifications, carrying out inspections and administering the work. The Chinese Military Engineering Commission controlled construction. Some 300,000 impressed laborers and 75,000 contract workers were employed on the project. Kenerson found that he had to teach them about soil mechanics, and then supervise them to ensure what he told them was put into practice.

Chinese laborers assembled for the project were organized in groups of 40,000 to 100,000 according to their local hsien (districts); each hsien was responsible for supplying a quota of workers. Workers had to provide their own tools and bring ninety days' rations with them. Food and accommodation were provided by the Chinese War Area Service Corps. The Chinese authorities insisted that workers from different hsien could not be mixed, so each hsien was allocated a portion of the project. The workers established temporary camps near the bases, which minimized travel time and facilitated health care and sanitation. Cooks provided meals of rice and steamed vegetables in baskets. Meat was provided once a week.

Since communications between China and India were solely by air, it was impractical to bring cement, asphalt or concrete mixers to China from India. The Chinese airfields had to be made entirely from local rock, gravel and sand. Farrell sent some small rock crushers and provided a detachment of engineers to install the fuel handling systems. Because the B-29 runways could not be brought up to standard, they were built to the full length of 8,500 feet (2,600 m) to allow for an extra margin of safety. They were 19 inches (48 cm) deep, with 52 hardstands for each. The accompanying fighter strips were 4,000 feet (1,200 m) long, 150 feet (46 m) wide, and 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 cm), with 4 to 8 hardstands each.

Some 1,000 ox carts, 15,000 wheelbarrows and 1,500 trucks were used to carry building materials. There were no bulldozers, power shovels or graders. The topsoil and some of the subsoil was removed, with hoes, and was carried away in wicker baskets on shoulder poles by men and boys. The subsoil was rolled flat using huge concrete rollers hauled by up to 300 workers. A layer of stones taken from nearby streams was laid down using wheelbarrows. Women and girls shaped the stones with hammers and chisels so they would not shift about. A slurry of topsoil and subsoil was laid atop the rocks as a binder, which was then rolled flat. Successive layers of rock and slurry were laid down. Sanders landed the first B-29 at Kwanghan on 24 April, and all four airfields were completed by 10 May 1944.

Ceylon

In addition to raids on Japan from bases in China, the Sextant Conference also approved attacks on the oil refineries in the Dutch East Indies by B-29s based in India, staging through Ceylon, with a target date of 20 July 1944. Although the southeast corner of Ceylon would have been the best location from a tactical point of view, being closest to Palembang, it was rejected due to the poor communications with that part of the island.

Airbase construction in Ceylon was a SEAC responsibility. When Kuter paid Mountbatten a visit in Colombo on 5 March, he found work under way on bomber airstrips at Kankesanturai in the north and Katunayake in the west, with completion dates in late 1944 or early 1945. Neither was well-situated for the proposed B-29 missions. The British then offered to extend airfields at Minneriya and China Bay, and this was accepted. By April it was apparent that the deadline could not be met. Work on Minneriya was suspended and effort concentrated on China Bay. By mid-July there it had a 7,200-foot (2,200 m) runway with hardstands, fuel pumps and accommodation for 56 B-29s.

Deployment

Sealift and airlift

The Matterhorn plan called for 20,000 troops and 200,000 short tons (180,000 t) of cargo to be shipped from the United States to CBI between 1 January and 30 June 1944, followed by 20,000 short tons (18,000 t) of fuel per month starting in April 1944. This would not have been a major undertaking for the European Theater of Operations, but movement to CBI was complicated by the long distance from the United States, the poor state of communications within the theater, and the low priority of CBI, especially with regard to shipping. The proviso at Sextant that Matterhorn shipments not materially affect other approved operations in CBI conflicted with the tight timetable and had to be disregarded.

High priority passengers and freight traveled by air. The Air Transport Command (ATC) ran a route via Natal, Khartoum and Karachi. The trip could take as few as six days, but personnel were often bumped from flights in favour of more important passengers, and many took over a month. The advance party of the XX Bomber Command, which included Wolfe, left Morrison Field in twenty C-87 transports on 5 January 1944 and arrived in New Delhi eight days later. Wolfe established his headquarters at Kharagpur, which was situated at a junction on Bengal Nagpur Railway lines serving the airfields. The Hijli Detention Camp was taken over to serve as his headquarters building.

It was originally intended that all air crews, both regular and relief, would fly in B-29s, but this was discarded in favor of carrying a spare engine in each plane in lieu of passengers. A sea-air service was instituted, sailing from Newark, New Jersey, to Casablanca, and then by air to Karachi. Twenty-five Douglas C-54 Skymaster aircraft were assigned to this service, which ran from 8 April to 1 June, and carried 1,252 passengers and 250 replacement Wright R-3350 engines. Stilwell provided this from CBI's allotment of ATC flights. In March, Arnold assigned three squadrons with eighteen Curtiss C-46 Commando each to support Matterhorn; one was assigned to the Hump run while the other two joined the ATC's North African Wing. They lacked the range of the C-54s and had to make more stopovers but they hauled 333 short tons (302 t) per month in June and July, which included another 225 spare Wright R-3350 engines. Matterhorn was also allocated 50 short tons (45 t) per month from the regular ATC supply to CBI.

Cargo ships usually went to Calcutta and troop ships to Bombay, which was safer. The ports of India were congested and inefficient. Allied shipping losses had been lower than anticipated in the second half of 1943, so more cargo ships were available. By 19 February 1944, 52,000 short tons (47,000 t) of supplies were en route to CBI. Troopships were harder to find. Ships bound for CBI went via the Pacific, sailing south of Australia, or the Atlantic via the Panama and Suez Canals. A Liberty ship took about sixty days to make the voyage from the United States to India, so it could only make two round trips per year. A contingent that included seven maintenance squadrons departed from Newport News on 12 February with a Liberty ship convoy to Oran. From there they were taken to Bombay on the liner SS Champollion, which they reached on 1 April. Other units sailed from Casablanca on the Dutch liner SS Volendam on 22 February, and reached Bombay on 25 April.

Eight maintenance squadrons embarked from Los Angeles on the troopship USS Mount Vernon on 27 February and sailing via Melbourne, Australia, reached Bombay on 31 March. From there it took a week to travel across India to Kharagpur by train. On contingent made the trip from the United States to Kharagpur in 34 days, but most took eight to ten weeks. By 10 May, the XX Bomber Command reported 21,930 personnel on hand. This included some who were already stationed in CBI, and some who had arrived by air, but about 20,000 of them had arrived by sea in March and April.

B-29 deployment

The construction of airfields in China and India with unusually long runways could not be concealed from the Japanese. Nonetheless, the B-29 Hobo Queen, commanded by Colonel Frank R. Cook, flew to RAF Bassingbourn in the UK on 8 March as part of a deception plan that the B-29 would be deployed to Europe. It departed the UK on 1 April, and became the second B-29 to reach its destination when it touched down at Kharagpur on 6 April; the first, Gone With the Wind, piloted by Harman, reached Chakulia on 2 April. The B-29s of the 58th Bombardment Wing began departing for India on 24 March, setting out in daily increments of nine or ten aircraft, with the trip expected to take up to five days. The chosen route was from Salina to Gander Lake (2,580 miles, 4,150 km), Marrakech (2,700 miles, 4,300 km), Cairo (2,350 miles, 3,780 km), Karachi (2,400 miles, 3,900 km) and Calcutta (1,500 miles, 2,400 km), a total of 11,530 miles (18,560 km). Air crew were not informed of their final destination.

By 15 April, only 32 aircraft had arrived at their stations. One B-29 crashed on takeoff from Marrakesh after the pilot forgot to extend the flaps. Another was grounded in Cairo for two weeks while engineers replaced all four engines. Two were lost in Cairo. One developed engine trouble soon after takeoff and crashed and burned on landing when it attempted to land. Another crashed on landing when its nose landing gear collapsed. All the crewmen survived these accidents, but five died when one crashed in Karachi in a sandstorm. Another B-29 was also lost there, and were grounded from 21 to 29 April while investigations were conducted into the causes. In all, five B-29s were lost and four damaged en route, but 130 aircraft had arrived safely by 8 May. Wolfe reported to Arnold on 26 April 1944 that: "The airplanes and crews got off to a bad start due to late production schedules, difficult modifications, inclement weather, and the sheer pressure of time necessary to meet the early commitment date."

| Group | Assigned to | Forward deployment |

| 40th Bombardment Group | Chakulia Airfield, India | Hsinching Airfield (A-1), China |

| 444th Bombardment Group | Dudhkundi Airfield, India | Kwanghan Airfield (A-3), China |

| 462nd Bombardment Group | Piardoba Airfield, India | Kuinglai (Linqiong) Airfield (A-5), China |

| 468th Bombardment Group | Kalaikunda Airfield, India | Pengshan Airfield (A-7), China |

Fighters

The deception plan was a failure; the Japanese made it known through radio broadcasts that they were well aware of the deployment of the B-29s. Although Calcutta was bombed, the B-29 airfields in Bengal lay close to the limit of the range of Japanese bombers. The airfields around Chengtu were well within range though. For this reason Chennault had asked for a fighter group to defend the airfields, and the Matterhorn plan had called for two. At the Sextant Conference the Combined Chiefs of Staff had decided to transfer two fighter groups from Italy.

The 33rd and 81st Fighter Groups were selected. To control the fighters, the Fourteenth Air Force activated the 312th Fighter Wing on 13 March, and Brigadier General Adlai H. Gilkeson assumed command twelve days later. Chennault recommended that the groups be equipped with North American P-51 Mustang fighters, but they had to be equipped with the less fuel efficient Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. Stratemeyer asked that the P-47s be sent from the United States, and the two groups conduct their conversion training in CBI.

If shipped normally, they would not arrive in Karachi before May, so the U.S. Navy made the escort carriers USS Mission Bay and Wake Island available to deliver the first hundred P-47s; the remaining fifty followed on freighters. The deployment of the two groups was delayed by their participation in the Battle of Anzio, but their flight echelons moved by air in mid-February, and the ground echelons moved by sea, embarking from Taranto, and arriving at Bombay on 20 March. The P-47s arrived at Karachi on 30 March, allowing conversion training to commence.

Stilwell was sufficiently concerned about the security of the Chengtu airfields to recommend that B-29 operations be postponed by a month. Permission for this was not forthcoiming, so the 33rd Fighter Group's 59th Fighter Squadron was sent to Szechwan with its old P-40s. It provided Chengtu's sole air defense until May, when the rest of the 33rd Fighter Group, the 58th and 60th Fighter Squadrons, arrived with their P-47s. The 81st Fighter Group's 92nd Fighter Squadron deployed to Kwanghan on 15 May, but the 91st and 93rd Fighter Squadrons did not join it until July. In the event, the Japanese response was not as intense as had been feared, and the late deployment of the fighters eased the burden of sticking fuel at Chengtu.

Campaign

Bangkok

Main article: Bombing of Bangkok in World War IIWolfe launched the first B–29 Superfortress combat mission on June 5, 1944, against Japanese Makkasan railway yard facilities in Bangkok, Thailand, about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) away. Of the 98 bombers that took off from India, 77 hit their targets, dropping 368 tons of bombs. Encouraged by the results, XX Bomber Command prepared for the first raids against Japan.

Bombing of Yawata

Main article: Bombing of Yawata (June 1944)Ten days later, sixty-eight Superfortresses took off at night from staging bases at Chengtu to bomb the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata on Kyūshū, more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km) away. The June 15, 1944, mission – the first raid on the Japanese home islands since the Doolittle raid of April 1942 – marked the beginning of the strategic bombardment campaign against Japan. Like the Doolittle attack, it achieved little physical destruction. Only forty-seven of the sixty-eight B–29s airborne hit the target area; four aborted with mechanical problems, four crashed, six jettisoned their bombs because of mechanical difficulties, and others bombed secondary targets or targets of opportunity. Only one B–29 was lost to enemy aircraft over the target, while another was strafed and destroyed by Japanese aircraft after making an emergency landing at Neihsiang.

The second full-scale strike did not occur until July 7, 1944. By then, Arnold, impatient with Wolfe's progress, had replaced him temporarily with Brigadier General LaVern G. Saunders, until Major General Curtis E. LeMay could arrive from Europe to assume permanent command. Unfortunately, the three-week delay between the first and second missions reflected serious problems that prevented a sustained strategic bombing campaign from China against Japan. Each B–29 mission consumed tremendous quantities of fuel and bombs, which had to be shuttled from India to the China bases over the Himalayas, the world's highest mountain range. For every Superfortress combat mission, the command flew an average of six B–29 round-trip cargo missions over the Hump, using both tactical aircraft and B-29s modified as fuel tankers. When it was immediately apparent that the operation would never be self-sustaining, the Air Transport Command was called upon to support Matterhorn with allocations on its Hump airlift, taken from the allocations to the Fourteenth Air Force already in China. In September 1944 70 C-109s were added to the effort, flown by surplus B-29 crews, but XX Bomber Command, fearful of diversions to other agencies, resisted all attempts to have them operated by ATC. Its transport procedures contradicted those of ATC, however, limiting its efficiency, and beginning in November 1944 its B-29s were withdrawn from the airlift and the C-109s transferred to ATC. With plans already developed to shut down B-29 forward basing in China at the end of January 1945, ATC took over the logistical supply of the bases in China, too late to provide the volume required to stockpile materiel. In the end, 42,000 tons of cargo were delivered over the Hump to XX Bomber Command between April 1944 and January 1945, nearly two-thirds of it by ATC.

Main article: Operation BoomerangRange presented another problem. Tokyo, in eastern Honshū, lay more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from the Chinese staging bases, out of reach of the B–29s. Kyūshū, in southwestern Japan, was the only one of the major home islands within the 1,600 miles (2,600 km) combat radius of the Superfortress. Targets in South East Asia also involved lengthy flights, with the Operation Boomerang raid which was conducted against Palembang on 10/11 August requiring a round trip of 3,855 miles (6,204 km).

The very heavy bomber still suffered mechanical problems that grounded some aircraft and forced others to turn back before dropping their bombs. Even those B–29s that reached the target area often had difficulty in hitting the objective, partly because of extensive cloud cover or high winds. Larger formations could have helped compensate for inaccurate bombing, but Saunders did not have enough B–29s to dispatch large formations. Also, the Twentieth Air Force periodically diverted the Superfortresses from strategic targets to support theater commanders in Southeast Asia and the southwestern Pacific. For these reasons, the XX Bomber Command and the B–29s largely failed to fulfill their strategic promise.

On August 20, LeMay arrived to breathe new energy into the XX Bomber Command. The former Eighth Air Force group and wing commander had achieved remarkable success with strategic bombing operations in Europe, testing new concepts such as stagger formations, the combat box, and straight-and-level bombing runs. The youngest two-star general in the Army Air Forces had also revised tactics, tightened and expanded formations, and enhanced training for greater bombing precision. He inaugurated a lead-crew training school so that formations could learn to drop as a unit on cue from the aircraft designated as the lead ship.

During his first two months at XX Bomber Command, LeMay had little more success than Wolfe or Saunders. The command continued to average only about one sortie a month per aircraft against Japan's home islands. When Douglas MacArthur invaded the Philippines in October 1944, LeMay diverted his B-29s from bombing Japanese steel facilities to striking enemy aircraft factories and bases in Formosa, Kyūshū, and Manchuria.

Meanwhile, LeMay gained the support of Communist leader Mao Zedong, who controlled parts of northern China. Willing to help against a common enemy, Mao agreed to assist downed American airmen and to locate in northern China a weather station that would provide better forecasts for the XX Bomber Command's raids on the Japanese in Manchuria and Kyūshū. Hoping to gain American recognition of his own regime, Mao suggested that the Americans set up B–29 bases in northern China like those in Chiang Kai-shek's area of control in southern China. LeMay declined, however, because he found it difficult enough to supply the airfields at Chengtu.

Ichi-Go and the first "fire raid" of Hankow (Wuhan)

In late 1944, the Japanese offensive Operation Ichi-Go in China probed toward the B–29 and Air Transport Command bases around Chengdu and Kunming. To slow the enemy advance, Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault of the Fourteenth Air Force asked for raids on Japanese supplies at Hankow (an area now part of present-day Wuhan), and the Joint Chiefs directed LeMay to hit the city with firebombs. On December 18, LeMay launched the fire raid, sending eighty-four B–29s in at medium altitude with five hundred tons of incendiary bombs. The attack left Hankow burning for three days, proving the effectiveness of incendiary weapons against the predominantly wooden housing stock of the Far East.

By late 1944, American bombers were raiding Japan from the recently captured Marianas, making operations from the vulnerable and logistically impractical China bases unnecessary. In January 1945, the XX Bomber Command abandoned its bases in China and concentrated 58th Bomb Wing resources in India. The transfer signaled the end of Matterhorn. During the same month, LeMay moved to the Marianas, leaving command of the XX Bomber Command in India to Brig. Gen. Roger M. Ramey. Between January and March, Ramey's B–29s assisted Mountbatten in the South-East Asian theatre, supporting British and Indian ground forces in Burma by targeting rail and port facilities in Indochina, Thailand, and Burma. More distant targets included refineries and airfields in Singapore, Malaya, as well as Palembang and other locations in the Netherlands East Indies. The 58th, the only operational wing of the XX Bomber Command, remained in India until the end of March 1945, when it moved to the Marianas to join the XXI Bomber Command.

XX Bomber Command stopped being an operational command at the end of March 1945 when the 58th Bomb Wing moved from India to the Marianas and control of the wing passed to the XXI Bomber Command.

Combat missions

| Mission | Date | Primary target | Groups | Up | Bombed | Lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 June 1944 | Makkasan railway yards, Bangkok, Thailand | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 98 | 77 | 5 |

| 2 | 15 June 1944 | Yahata Steel Works, Yahata, Fukuoka, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 68 | 47 | 7 |

| 3 | 7 July 1944 | Sasebo Shipyard, Nagasaki, Japan | 444, 468 | 18 | 14 | 0 |

| 4 | 29 July 1944 | Showa Steel Works, Anshan, Manchuria | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 96 | 75 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 August 1944 | Baraban oil refineries, Palembang, Dutch East Indies | 444, 468 | 54 | 39 | 2 |

| 6 | 10 August 1944 | Nagasaki, Japan | 444, 468 | 29 | 24 | 1 |

| 7 | 20 August 1944 | Yahata Steel Works, Yahata, Fukuoka, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 88 | 71 | 14 |

| 8 | 8 September 1944 | Showa Steel Works, Anshan, Manchuria | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 88 | 72 | 3 |

| 9 | 26 September 1944 | Showa Steel Works, Anshan, Manchuria | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 109 | 83 | 0 |

| 10 | 14 October 1944 | Takao Naval Air Station, Okayama, Formosa | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 131 | 106 | 2 |

| 11 | 16 October 1944 | Okayama, Formosa | 444, 462 | 49 | 38 | 0 |

| 11 | 16 October 1944 | Heito, Formosa | 468 | 24 | 20 | |

| 12 | 17 October 1944 | Einansho Airfield, Tainan, Formosa | 40 | 30 | 10 | 0 |

| 13 | 25 October 1944 | Omura, Nagasaki, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 75 | 58 | 0 |

| 14 | 3 November 1944 | Malegon Railway Yards, Rangoon, Burma | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 50 | 44 | 1 |

| 15 | 5 November 1944 | Singapore | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 74 | 53 | 3 |

| 16 | 5 November 1944 | Omura Aircraft Factory, Nagasaki, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 93 | 29 | 2 |

| 17 | 11 November 1944 | Omura Aircraft Factory, Nagasaki, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 96 | 63 | 2 |

| 18 | 27 November 1944 | Bangkok, Thailand | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 60 | 55 | 3 |

| 19 | 7 December 1944 | Manchuria Aviation Company, Mukden, Manchuria | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 70 | 40 | 9 |

| 20 | 14 December 1944 | Rama VI Bridge, Bangkok, Thailand | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 45 | 33 | 1 |

| 21 | 18 December 1944 | Hankow, China | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 94 | 85 | 6 |

| 22 | 19 December 1944 | Omura, Nagasaki, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 36 | 17 | 5 |

| 23 | 21 December 1944 | Manchuria Aviation Company, Mukden, Manchuria | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 55 | 40 | 0 |

| 24 | 2 January 1945 | Rama VI Bridge, Bangkok, Thailand | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 49 | 44 | 2 |

| 25 | 6 January 1945 | Omura, Nagasaki, Japan | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 48 | 29 | 2 |

| 26 | 9 January 1945 | Formosa | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 46 | 40 | 0 |

| 27 | 11 January 1945 | Floating Dry Dock and King George VI Graving Dock, Singapore | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 43 | 27 | 0 |

| 28 | 14 January 1945 | Kagi Airfield, Chiayi County, Formosa | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 82 | 54 | 0 |

| 29 | 17 January 1945 | Shinchiku, Formosa | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 90 | 78 | 2 |

| 30 | 25 January 1945 | Mine-laying, Indochina area | 462 | 26 | 25 | 0 |

| 31 | 25 January 1945 | Mine-laying, Singapore area | 444, 462 | 45 | 41 | 1 |

| 32 | 27 January 1945 | Saigon Naval Shipyard | 40 | 25 | 22 | 0 |

| 33 | 1 February 1945 | Floating Dry Dock | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 104 | 78 | 0 |

| 34 | 7 February 1945 | Saigon Naval Shipyard | 444, 462 | 66 | 44 | 0 |

| 34 | 7 February 1945 | Phnom Penh, Indochina | 444, 462 | 17 | 0 | |

| 35 | 7 February 1945 | Rama VI Bridge, Bangkok, Thailand | 40, 468 | 60 | 59 | 2 |

| 36 | 11 February 1945 | Rangoon, Burma | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 60 | 56 | 1 |

| 37 | 19 February 1945 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaya | 444, 468 | 58 | 48 | 0 |

| 38 | 24 February 1945 | Empire Dock, Singapore | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 117 | 105 | 0 |

| 40 | 24 February 1945 | Mine-laying, Johore Strait area | 444 | 12 | 10 | 0 |

| 41 | 2 March 1945 | Singapore Naval Base | 40, 444, 462, 468 | 62 | 48 | 1 |

| 39 | 4 March 1945 | Mine-laying, Yangtze River, China | 468 | 30 | 24 | 0 |

| 43 | 10 March 1945 | Railway yards, Kuala Lumpur, Malaya | 468 | 29 | 23 | 0 |

| 42 | 12 March 1945 | Samboe Island oil storage, Singapore | 40 | 15 | 11 | 0 |

| 42 | 12 March 1945 | Bukum Island oil storage, Singapore | 444 | 30 | 21 | 0 |

| 42 | 12 March 1945 | Sebarok Island oil storage, Singapore | 462 | 15 | 11 | 0 |

| 44 | 17 March 1945 | Rangoon, Burma | 40, 468 | 39 | 39 | 0 |

| 45 | 22 March 1945 | Rangoon, Burma | 444, 462 | 30 | 28 | 0 |

| 45 | 22 March 1945 | Mingaladon railway station, Rangoon, Burma | 468 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| 46 | 28 March 1945 | Mine-laying, Yangtze River, China | 468 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| 47 | 28 March 1945 | Mine-laying, Saigon area and Cam Ranh Bay, Indochina | 468 | 18 | 16 | 0 |

| 48 | 28 March 1945 | Mine-laying, Johore Strait and Riau Strait, Malaya | 444 | 33 | 32 | 0 |

| 49 | 29 March 1945 | Bukum Island oil storage, Singapore | 40, 462 | 26 | 24 | 0 |

Assessment

The American Bomber Summary Survey states that "Approximately 800 tons of bombs were dropped by China-based B-29s on Japanese home island targets from June 1944 to January 1945. These raids were of insufficient weight and accuracy to produce significant results." The XX Bomber Command failed to achieve the strategic objectives that the planners had intended for Operation Matterhorn, largely because of logistical problems, the bomber's mechanical difficulties, the vulnerability of Chinese staging bases, and the extreme range required to reach key Japanese cities. Although the B–29s achieved some success when diverted to support Chiang Kai-shek's forces in China, MacArthur's offensives in the Philippines, and Mountbatten's efforts in the Burma campaign, they generally accomplished little more than the B-17s and B-24s of the Fourteenth, Fifth, Thirteenth and Tenth Air Forces.

Chennault considered the Twentieth Air Force a liability and thought that its supplies of fuel and bombs could have been used more profitably by the Fourteenth Air Force. The XX Bomber Command consumed almost 15 percent of the Hump tonnage per month during Matterhorn. Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, who replaced Stilwell as the American senior commander in the China theater in October 1944, agreed. The two were happy to see the B–29s leave China and India. Yet, despite those objections, Matterhorn did benefit the Allied war effort. Using the China bases bolstered Chinese morale and, more important, it allowed the strategic bombing of Japan to begin six months before bases were available in the Marianas. The Matterhorn raids against the Japanese home islands also demonstrated the B–29's effectiveness against Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft artillery. Operations from the Marianas would profit from the streamlined organization and improved tactics developed on the Asian mainland.

Footnotes

- The name "Superfortress" was not assigned until March 1944.

- ^ The 395th, 679th, 771st and 795th Bombardment Squadrons were disbanded in October 1944.

- ^ The bomb maintenance squadrons were disbanded in October 1944.

- By March 1945 another 255 B-29s had made their way to CBI, and only three were lost en route.

- The 444th Bombardment Group was based at Charra Airfield until July, but that base was not capable of sustaining very heavy bomber operations.

Notes

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 6–8.

- "Superfortress". The Mirror. Vol. 22, no. 1139. Western Australia. 11 March 1944. p. 8. Retrieved 24 August 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- Boyne 2012, p. 96.

- Boyne 2009, p. 52.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 723–724.

- ^ Coffey 1982, p. 334.

- Haulman 1999, p. 6.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 482.

- Moore, Christopher (12 August 2020). "Defending the Superbomber: The B-29's Central Fire Control System". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Haulman 1999, pp. 6–7.

- Boyne 2012, p. 95.

- "70 Years Ago: Remembering The Crash Of Boeing's Superfortress". KUOW. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Cate 1953, pp. 9–13.

- United States 1968, p. 687.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 17–19.

- ^ United States 1970, pp. 995–999.

- Hayes 1982, pp. 493–495.

- Hayes 1982, p. 497.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 20–21.

- United States 1961, p. 172.

- Hayes 1982, pp. 496–497.

- United States 1961, pp. 771–773.

- Cate 1953, pp. 22–26.

- Hayes 1982, pp. 500–501.

- Hayes 1982, p. 493.

- ^ United States 1961, p. 780.

- Hayes 1982, pp. 546–547.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 592–593.

- Cate 1953, pp. 30–31.

- Hayes 1982, pp. 554–560.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 53–54.

- Mays 2016, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Mays 2016, pp. 23–26.

- "Alva L. Harvey Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- "Major General Richard Henry Carmichael > Air Force > Biography Display". United States Air Force. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- Ruane, Michael E. (7 December 2008). "Pearl Harbor: How much did the U.S. know before the Japanese attacked Hawaii?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- "Major General Lewis R. Parker > Air Force > Biography Display". United States Air Force. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 39.

- Coffey 1982, p. 343.

- Cate 1953, p. 23.

- Cate 1953, p. 55.

- Li 2020, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 123.

- Maurer 1982, pp. 485, 705, 746, 760.

- Cate 1953, pp. 45–46.

- Romanus & Sunderland 1956, pp. 113–114.

- Cline 1951, pp. 254–255.

- Cate 1953, p. 56.

- Coffey 1982, p. 342.

- ^ Boyne 2012, pp. 96–97.

- Coffey 1982, pp. 334–335.

- Coffey 1982, pp. 341–342.

- Cate 1953, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Dod 1966, pp. 438–440.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Madsen 1944, pp. 332–334.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Dod 1966, p. 450.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 64–65.

- "Airfield Construction 1942-44". China-Burma-India Theater of World War II. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Army Pipelines in India". China-Burma-India Theater of World War II. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- Romanus & Sunderland 1956, p. 275.

- "52 Dead In Fire At Uluberia Sequel To Petrol Catching Fire". The Indian Express. 3 July 1944. p. 2. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Romanus & Sunderland 1956, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Dod 1966, p. 451.

- ^ Dod 1966, pp. 440–441.

- ^ Romanus & Sunderland 1956, p. 77.

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 70.

- ^ Bell 2014, p. 45.

- "Black Markets in China". The Argus (Melbourne). No. 30, 602. Victoria, Australia. 26 September 1944. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Bell 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Romanus & Sunderland 1956, p. 115.

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 71.

- Bell 2014, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 73–76.

- "USS Mount Vernon - War Diary, 2/1-27/44". National Archives. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- "USS Mount Vernon - War Diary, 3/1-31/44". National Archives. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 78.

- "The First B-29 in England". The Washington Times. No. 8. Winter 2005. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- ^ Mays 2016, p. 30.

- Mays 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 79.

- Maurer 1983, pp. 96–97, 318–319, 337–338, 343–344.

- Cate 1953, pp. 62, 65, 79.

- ^ Cate 1953, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Haulman, Chapter Over the Hump to Matterhorn p.5

- Tillman, Barret (2010). Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan 1942–1945. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-84176-161-9.

- Cate 1953, p. 102.

- "The US Firebombing of Wuhan, Part 1". www.chinaww2.com. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- Mann 2004, pp. 113–114.

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey 1946, p. 16.

- ^ Haulman 1999, pp. 12–13.

- Romanus & Sunderland 1956, pp. 468–471.

References

- Bell, Raymond E. Jr. (Fall 2014). "With Hammers & Wicker Baskets: The Construction of U.S. Army Airfields in China during World War II". Army History (93): 30–54. ISSN 1546-5330. JSTOR 26300287.

- Boyne, Walter J. (June 2009). "Carbon Copy Bomber" (PDF). Air & Space Forces Magazine. pp. 52–56. ISSN 0730-6784. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Boyne, Walter J. (February 2012). "The B-29's Battle of Kansas" (PDF). Air & Space Forces Magazine. pp. 94–97. ISSN 0730-6784. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Cate, James (1953). "The Twentieth Air Force and Matterhorn". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James (eds.). The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944 to August 1945 (PDF). The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. V. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Cline, Ray S. (1951). Washington Command Post: The Operations Division (PDF). United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 1-2. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Coffey, Thomas M. (1982). Hap: The Story of the U.S. Air Force and the Man Who Built It, General Henry H. "Hap" Arnold. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-36069-7. OCLC 8474856.

- Dod, Karl C. (1966). The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Japan (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Haulman, Daniel L. (1999). Hitting Home: The Air Offensive Against Japan (PDF). The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. Air Force History and Museums Program. OCLC 1101033871. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- Hayes, Grace Person (1982). The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II: The War Against Japan. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-269-7. OCLC 7795125.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1988). Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-59-5. OCLC 631301640. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Li, Xiaowei (2020). The Superfortress in China. Montreal, Quebec: Royal Collins Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 978-14878-0094-9. OCLC 1125081405.

- Madsen, Kenneth E. (October 1944). "Army Engineers and the Superfortress". The Military Engineer. 36 (228): 332–334. ISSN 0026-3982. JSTOR 44606719.

- Mann, Robert A. (2004). The B-29 Superfortress: A Comprehensive Registry of the Planes and Their Missions. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1787-0. OCLC 55962447.

- Maurer, Maurer (1982). Combat Squadrons of the Air Force World War II (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. OCLC 72556. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-02-1. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- Mays, Terry M. (2016). Matterhorn: The Operational History of the US XX Bomber Command from India and China: 1944-1945. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military. ISBN 978-0-7643-5074-0. OCLC 927401983.

- Romanus, Charles F.; Sunderland, Riley (1956). Stilwell's Command Problems (PDF). Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 1259571. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- United States (1968). The Conferences at Washington, 1941–1942, and Casablanca, 1943. Foreign Relations of the United States. Washington, D. C.: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 213502760. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- United States (1970). The Conferences at Washington and Quebec, 1943. Foreign Relations of the United States. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 213773675. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- United States (1961). The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943. Foreign Relations of the United States. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 394877. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey (1 July 1946). Summary Report (Pacific War) (Report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 332839. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

External links

- Johnson, E.R. (26 May 2006). "Operation Matterhorn". Historynet. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- China Builds Airfields For B-29 Bombers (1944) on YouTube

- B-29 Flight Procedure and Combat Crew Functioning. United States Army Air Forces. 1944. TF1-3353. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

| Airfields |

|  | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||