This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Austronesier (talk | contribs) at 11:56, 12 November 2023 (→Other classifications). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:56, 12 November 2023 by Austronesier (talk | contribs) (→Other classifications)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Low Franconian dialect group ‹ The template Infobox language is being considered for merging. ›| Kleverlandish | |

|---|---|

| Low Rhenish | |

| Native to | Germany, Netherlands |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

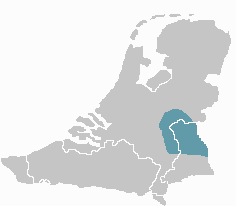

Kleverlandish dialect area (the southern extent in this map follows the Uerdingen line). Kleverlandish dialect area (the southern extent in this map follows the Uerdingen line). | |

Kleverlandish (Template:Lang-nl; Template:Lang-de) is a group of Low Franconian dialects spoken on both sides of the Dutch-German border along the Meuse and Rhine rivers.

Extent and terminology

Kleverlandish varieties are spoken in the Netherlands in the northernmost part of Dutch Limburg, in the northeastern most part of North Brabant (Land van Cuijk), and in the southeastern part of Gelderland (around Nijmegen), and in Germany in the districts of Cleves and Wesel in northwestern North Rhine-Westphalia. To the northeast, Kleverlandish borders on the Low Saxon speech area, its western border is the diphthongisation line. Traditionally, its southern extent is defined by the Uerdingen line (the ik-ich-isogloss), but many Dutch and German scholars place it further to the north based on wider criteria than the ik-ich-isogloss.

Originally, the term Kleverländisch referred only to the dialects in the German part of the speech area, which are also called Niederrheinsch (Low Rhenish) in traditional German dialectology. The dialects on the Dutch side were first classified as a distinct group by te Winkel (1898) (as "Saxon-East Franconian") and Van Ginneken (1917) ("Guelderish-Limburgish"). The close affinity between these dialect areas had long been recognized by Dutch and German scholars; but it was the Belgian dialectologist Jan Goossens who first introduced "Kleverlandish" (Template:Lang-nl) as an umbrella term for all varieties on both sides of the border.

Characteristics

Kleverlandish is characterized by several conservative features, such as the retention of -al-/-ol- before consonants (e.g. Kleverlandish ald 'old'; in most Low Franconian dialects, -l- is vocalized in this environment (Limburgish aod, Standard Dutch oud), while Low Saxon dialects retains the -l- but merge the vowels to -o- (Low Saxon old)) or the retention of historically long high vowels (diphthongized in most Low Franconian dialects to the west, e.g. Klevelandish is vs. Standard Dutch ijs < *īs). A typical West Low Franconian feature is the fronting of /uː/ to /yː/ (e.g. hüs 'house' < *hūs) which however did not fully radiate into the German area of Kleverlandish, where in many areas it only affects part of the vocabulary.

Status

In much of the Kleverlandish speech area in both the Netherlands and Germany, speakers are shifting from Kleverlandish to regional colloquial forms of the resepctive national languages, Dutch and German, with a higher degree of decline of dialect usage in Germany than in the Netherlands. In Dutch Limburg, Kleverlandish varieties spoken within the province are included in the official recognition of Limburgish as a regional language (even though they do not belong to Limburgish in a dialectological sense). Official recognition does not extend to other Dutch provinces, nor to Germany.

Other classifications

In the widely reproduced dialect map by Jo Daan [nl], Kleverlandish dialects are divided over two dialect groups: varieties in Gelderland are assigned to South Guelderish (which also includes dialects spoken in the southwest of Gelderland which have taken part in the Hollandic-Brabantian diphthongisation), while the varieties in North Brabant and Limburg are included in North Brabantian.

Notes

- Thus, the dialects of e.g. Venlo, Moers and Duisburg are excluded from Kleverlandish.

- In Gelderland, efforts for official recognition have begun in 2023, see "Petitie voor behoud Kleverlands in Gelderland gestart", Interreg Deutschland-Nederland.

Citations

- ^ De Vriend et al. 2008, p. 119.

- Wiesinger 1970b, pp. 331–332.

- Bakker & van Hout 2017.

- Giesbers 2008, p. 5.

- Swanenberg 2019, p. 3.

- Wiesinger 1970a, p. 142.

- Giesbers 2008, pp. 97–120.

- Daan 1969.

References

- Bakker, Frens; van Hout, Roeland (2017). "De indeling van de dialecten in Noord-Limburg en het aangrenzende Duitse gebied. Hoe relevant is de Uerdingerlijn als scheidslijn?". Nederlandse Taalkunde. 22 (3): 303–332. doi:10.5117/NEDTAA2017.3.BAKK.

- Daan, Jo (1969). Van Randstad tot Landrand. Bijdragen en Mededelingen der Dialectcommissie van de KNAW XXXVI. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers Maatschappij.

- De Vriend, Folkert; Giesbers, Charlotte; van Hout, Roeland; ten Bosch, Louis (2008). "The Dutch-German Border: Relating Linguistic, Geographic and Social Distances". International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing. 2 (1–2). Edinburgh University Press: 119–134. doi:10.3366/E1753854809000342.

- Giesbers, Charlotte (2008). Dialecten op de grens van twee talen. Een dialectologisch en sociolingüistisch onderzoek in het Kleverlands dialectgebied (PhD thesis). Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen.

- Wiesinger, Peter (1970a). Phonetisch-phonologische Untersuchungen zur Vokalentwicklung in den deutschen Dialekten, Band 1: Die Langvokale im Hochdeutschen. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Wiesinger, Peter (1970b). Phonetisch-phonologische Untersuchungen zur Vokalentwicklung in den deutschen Dialekten, Band 2: Die Diphthonge im Hochdeutschen. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Swanenberg, Jos (2019). "Grenzen aan de streektaal: De taalkundige en de culturele benadering van het Brabants in Nederland". In Veronique De Tier; Anne-Sophie Ghyselen; Ton van de Wijngaard (eds.). De wondere wereld van de streektaalgrenzen. Leiden: Stichting Nederlandse Dialecten. pp. 39–48.