This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Doc glasgow (talk | contribs) at 17:20, 15 May 2007 (→Plot summary: patronising - of course a 'plot summary' will tell people the plot). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

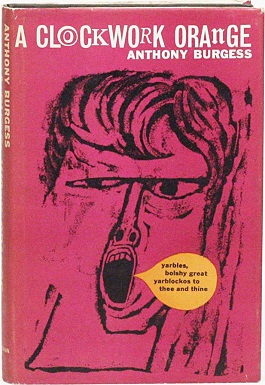

Revision as of 17:20, 15 May 2007 by Doc glasgow (talk | contribs) (→Plot summary: patronising - of course a 'plot summary' will tell people the plot)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Dust-jacket from the first edition Dust-jacket from the first edition | |

| Author | Anthony Burgess |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | William Heinemann (UK) |

| Publication date | 1962 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) & Audio Book (Cassette, CD) |

| Pages | 192 pages (Hardback edition) & 176 pages (Paperback edition) |

| ISBN | ] Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Template:Redirect6 A Clockwork Orange is a speculative fiction novel by Anthony Burgess, published in 1962, and later the basis for a 1971 film adaptation by Stanley Kubrick.

The novel was chosen by TIME Magazine as one of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to the present.

Plot introduction

Explanation of the novel's title

Anthony Burgess wrote that the title was a reference to an alleged old Cockney expression "as queer as a clockwork orange".¹ Due to his time serving in the British Colonial Office in Malaysia, Burgess thought that the phrase could be used punningly to refer to a mechanically responsive (clockwork) human (orang, Malay for "person"). It is possible, however, that Burgess invented the phrase as a play upon the expression "a work of pith and moment".

Burgess wrote in his later (Nov. 1986) introduction, titled A Clockwork Orange Resucked, that a creature who can only perform good or evil is "a clockwork orange — meaning that he has the appearance of an organism lovely with color and juice, but is in fact only a clockwork toy to be wound up by God or the Devil; or the almighty state."

In his essay "Clockwork Oranges"², Burgess asserts that "this title would be appropriate for a story about the application of Pavlovian, or mechanical, laws to an organism which, like a fruit, was capable of colour and sweetness". This title alludes to the protagonist's negatively conditioned responses to feelings of evil which prevent the exercise of his free will.

Point of view from one person

A Clockwork Orange is written in first person perspective from a seemingly biased and unreliable source. Alex never justifies his actions in the narration, giving a good sense that he is somewhat sincere; a narrator who, as unlikeable as he may attempt to seem, evokes pity from the reader through the telling of his unending suffering and later through his realization that the cycle will never end. Alex's perspective is effective in that the way that he describes events is easy to relate to even if the situations themselves are not. He uses words that are common in speech as well as Nadsat, the speech of the younger generation.

Plot summary

Part 1: Alex's world

Set in a dystopian future, the novel opens with the introduction of protagonist, fifteen-year-old Alex, who, with his gang members (known as "droogs") Dim, Georgie and Pete, roam the streets at night, committing crimes for enjoyment.

Essentially, the first part of the novel is a character study of the protagonist. We learn that Alex is articulate and clever, enjoys classical music (that particularly of Beethoven) and finds amusement during the evenings in committing crimes and acts of sexual violence — justifying himself through his narrative voice. We learn that Alex and his "droogs" have their own language known as Nadsat, and their own hierarchy, in which Alex is the leader. There is a general disregard for the law or for older generations — creating an image of a youth movement which is taking control of this fictional future. (This of course being the exaggeration of the concern that came with the changing values of the 1960s, in which teenagers were becoming decidedly more unruly and rebellious.)

Part 1 involves Alex reflecting on his illegal activity (which involves the rape of two 10-year-old girls, and also the wife of writer F. Alexander) and describes the treachery of the droogs which results in Alex's capture and then later, prison sentence.

The use of lyrical language and Nadsat somewhat masks the horrible imagery of Alex's actions, and, to some extent, Alex is able to draw empathy from the reader, through his friendly nature towards his audience (referring to them as his "only friends", etc.)

Part 2: The Ludovico Technique

After getting caught for his crimes Alex is sentenced to 14 years for murder. Alex gets a job as an assistant to the prison chaplain. He feigns an interest in religion, and amuses himself by reading the Bible for its lurid descriptions of "the old yahoodies (Jews) tolchocking (beating) each other", imagining himself taking part in "the nailing-in" (the Crucifixion of Jesus). Alex hears about an experimental rehabilitation programme called "the Ludovico Technique", which promises that the prisoner will be released upon completion of the two-week treatment, and will not commit crimes afterwards.

Partially by taking part in the fatal beating of a cellmate, Alex manages to become the subject in the first full-scale trial of the Ludovico Technique. The technique itself is a form of aversion therapy, in which Alex is given a drug that induces extreme nausea while being forced to watch graphically violent films for two weeks. Among the films shown are propaganda films such as Triumph of the Will, which includes Alex's beloved Beethoven. He pleads them to remove the music, but they refuse to edit it, saying it's 'for his own good', and that the music may be the 'punishment element'. At the end of the treatment, Alex is unable to carry out or even contemplate violent acts without crippling nausea. He is also unable to listen to music in general without experiencing the same jarring physical reaction.

Part 3: After prison

The third part of the novel concentrates mostly on the following punishment to which Alex is subjected after his treatment. Alex encounters many of his former victims, all of whom seek revenge upon him. He finds himself powerless to defend himself against them, due to feelings of sickness and fear of death, as a reaction to the violence. He finds he has been replaced by a lodger in his home, and wanders the streets, contemplating suicide. Alex falls into the hands of F. Alexander, the husband to the woman whom he earlier raped. Friends of the writer intend to use Alex as a weapon against the political party, exposing the terrible things that have been done to him. Although it is not clear as to whether the friends of F. Alexander intend it, their playing of a symphony by Otto Skadelig below Alex in a locked room drives him to throw himself out of a window instead of endure the pain of the treatment's conditioning. Alex's suicide attempt fails, and leads to his being cured, after the bad publicity for the political party that follows.

Touching on themes of the power struggles between old and young generations, the corruption of the police, and also politics, and attempted (but failed) suicide, the third section of the novel is the most reflective of the troubles of future society, mostly shown through the final chapter, where Alex reflects that he and his friends have either been killed (Georgie), fallen victim to the state (Dim's becoming a police officer) or outgrown their destructive behaviour (Pete). Alex finds that he no longer finds pleasure in "ultra-violence", and yearns for a mate, and a child of his own. Alex knows that the generation after his will probably be just as destructive, but that there won't be anything he can do — perhaps revealing Burgess's ultimate deliberation on the unruly youth.

Characters

Alex — The novel's protagonist and leader among his "droogs,". Alex often refers to himself as "Your Humble Narrator". At the point of raping two ten year old girls, Alex reveals himself as "Alex The Large". This was later the basis for Alex's surname DeLarge in the 1971 film.

George or Georgie — A droog of Alex's. Georgie attempts to undermine Alex's status as leader of the gang.

Pete — A droog of Alex's. The more rational, democratic member of Alex's gang.

Dim — A slow-witted droog of Alex's. The real brute force of the gang.

P.R. Deltoid — A social worker assigned to Alex, who monitors his progress through reform schools.

The Prison Chaplain (also the prison charlie, a take on Charlie Chaplin) — The character who first questions whether or not forced goodness is really better than chosen wickedness. The only character who is truly concerned about Alex's welfare; he is not taken seriously by Alex, though.

The Governor — The man who decides to let Alex "choose" to be the first reformed by the Ludovico Technique.

Dr. Brodsky — One of the co-founders of the Ludovico Technique. He at first seemed like a friend to Alex, and then introduced him to pain. Plays the "Bad Cop" role when talking to Alex before and after his sessions in the theater.

Dr. Branom — The other Co-Founder of the Ludovico Technique. He says much less than Brodsky and is interpreted as the "Good Cop" role when addressing Alex.

F. Alexander — An author writing, at the beginning of the novel, his own novel called A Clockwork Orange. His wife is raped by Alex and his droogs, and subsequently dies. He later takes Alex in and subjects him to his extremist friends. Shortly after meeting they try to kill him using the weaknesses caused by the Ludovico Technique. Template:Endspoiler

Differences in U.S. editions

Although the book is divided into three parts, each containing seven chapters (21 being a symbolic reference to the British age of majority at the time the book was written), the 21st chapter was omitted from the versions published in the United States until 1986. The film adaptation, which was directed by Stanley Kubrick, follows the American version of the book, ending prior to the events of the 21st chapter. Kubrick claimed that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay, but that he certainly never gave any serious consideration to using it.

Nadsat

The book, narrated by Alex, contains many words in a slang dialect which Burgess invented for the book, called Nadsat. It is a mix of modified Slavic words, Cockney rhyming slang, derived Russian (like "baboochka"), and words invented by Burgess himself. One of Alex's doctors explains the language to a colleague as "Odd bits of old rhyming slang; a bit of gypsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav propaganda. Subliminal penetration."

Awards and nominations

- 1983 - Prometheus Award (Preliminary Nominee)

- 1999 - Prometheus Award (Nomination)

- 2002 - Prometheus Award (Nomination)

- 2003 - Prometheus Award (Nomination)

- 2006 - Prometheus Award (Nomination)

Other adaptations

The best known adaptation of the novel to other forms is of course the 1971 film by Stanley Kubrick. But there have been others. In film, the earlier 1965 film by Andy Warhol entitled Vinyl was an adaptation.

Excerpts from the first two chapters of the novel were dramatized and broadcast on BBC TV's programme Tonight, 1962 (now lost, believed wiped).

After Kubrick's film was released, Burgess wrote a Clockwork Orange stage play. In it, Dr. Branom defects from the psychiatric clinic when she grasps that the aversion treatment has destroyed Alex's ability to enjoy music. The play restores the novel's ending: Alex deciding to start a family. One of Alex's early victims, a bearded trumpeter who plays "Singin' in the Rain" at the Korova milkbar, is modeled on Stanley Kubrick.

In 1990, a second play, titled A Clockwork Orange 2004, was written for the Royal Shakespeare Company. It makes no references to the film version, yet does away with the novel's ending.

Release details

- 1962, UK, William Heinemann (ISBN ?), Pub date ? December 1962, Hardcover

- 1962, US, W W Norton & Co Ltd (ISBN ?), Pub date ? ? 1962, Hardcover

- 1963, US, W W Norton & Co Ltd (ISBN ?), Pub date ? ? 1963, Paperback

- 1965, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN ?), Pub date ? ? 1965, Paperback

- 1969, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN ?), Pub date ? ? 1969, Paperback

- 1971, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN 0-345-02624-1), Pub date ? ? 1971, Paperback

- 1972, UK, Lorrimer, (ISBN 0-85647-019-8), Pub date 11 September 1972, Hardcover

- 1973, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-003219-3), Pub date 25 January 1973, Paperback

- 1977, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN 0-345-27321-4), Pub date 12 September 1977, Paperback

- 1979, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN 0-345-31483-2), Pub date ? April 1979, Paperback

- 1983, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN 0-345-31483-2), Pub date 12 July 1983, Unbound

- 1986, US, W. W. Norton & Company (ISBN 0-393-31283-6), Pub date ? November 1986, Paperback (Adds final chapter not previously available in U.S. versions)

- 1987, UK, W W Norton & Co Ltd (ISBN 0-393-02439-3), Pub date ? July 1987, Hardcover

- 1988, US, Ballantine Books (ISBN 0-345-35443-5), Pub date ? March 1988, Paperback

- 1995, UK, W W Norton & Co Ltd (ISBN 0-393-31283-6), Pub date ? June 1995, Paperback

- 1996, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-018882-7), Pub date 25 April 1996, Paperback

- 1996, UK, HarperAudio (ISBN 0-694-51752-6), Pub date ? September 1996, Audio Cassette

- 1997, UK, Heyne Verlag (ISBN 3-453-13079-0), Pub date 31 January 1997, Paperback

- 1998, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-027409-X), Pub date 3 September 1998, Paperback

- 1999, UK, Rebound by Sagebrush (ISBN 0-8085-8194-5), Pub date ? October 1999, Library Binding

- 2000, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-118260-1), Pub date 24 February 2000, Paperback

- 2000, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-029105-9), Pub date 2 March 2000, Paperback

- 2000, UK, Turtleback Books (ISBN 0-606-19472-X), Pub date ? November 2000, Hardback

- 2001, UK, Penguin Books Ltd (ISBN 0-14-100855-5), Pub date 27 September 2001, Paperback

- 2002, UK, Thorndike Press (ISBN 0-7862-4644-8), Pub date ? October 2002, Hardback

- 2005, UK, Buccaneer Books (ISBN 1-56849-511-0), Pub date 29 January 2005, Library Binding

See also

References

- A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music. Century Hutchinson Ltd. (1987). An extract is quoted on several web sites: , , .

- Burgess, Anthony (1978). Clockwork Oranges. In 1985. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-136080-3 (extracts quoted here)

- Vidal, Gore. "Why I Am Eight Years Younger Than Anthony Burgess," in At Home: Essays, 1982-1988, p. 411. New York: Random House, 1988. ISBN 0-394-57020-0.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. p. 72. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

Notes

- Burgess, A.: "A Clockwork Orange Resucked", Introduction to W.W. Norton 1986 Edition of A Clockwork Orange, page vi

External links

- Prometheus Hall Of Fame Nominees

- A Clockwork Orange title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- A Prophetic and Violent Masterpiece, a City Journal article.

- Comparison of Book and Film