This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Alex9788 (talk | contribs) at 19:33, 5 September 2007 (→In popular culture: Reword William Shatner sentence). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:33, 5 September 2007 by Alex9788 (talk | contribs) (→In popular culture: Reword William Shatner sentence)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the language. For other uses, see Esperanto (disambiguation).| Esperanto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created by | L.L. Zamenhof |

| Setting and usage | International auxiliary language |

| Users | (Native: approx. 1000; Fluent speakers: est. 100,000 to 2 million cited 1887) |

| Purpose | Constructed language

|

| Sources | vocabulary from Romance and Germanic languages; phonology from Slavic languages |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Akademio de Esperanto |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | eo |

| ISO 639-2 | epo |

| ISO 639-3 | epo |

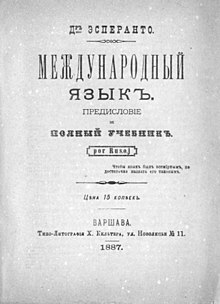

Audio file "Esperanto.ogg" not found is the most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. The name derives from Doktoro Esperanto, the pseudonym under which L. L. Zamenhof first published the Unua Libro in 1887. The word itself means 'one who hopes'. Zamenhof's goal was to create an easy and flexible language as a universal second language to foster peace and international understanding.

Although no country has adopted the language officially, it has enjoyed continuous usage by a community estimated at between 100,000 and 2 million speakers. By some estimates, there are about a thousand native speakers.

Today, Esperanto is employed in world travel, correspondence, cultural exchange, conventions, literature, language instruction, television (Internacia Televido) and radio broadcasting. Some state education systems offer elective courses in Esperanto, and there is evidence that learning Esperanto is a useful preparation for later language learning (see Propaedeutic value of Esperanto for more details).

History

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Esperanto was developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s by ophthalmologist Dr. Ludovic Lazarus Zamenhof, a Polish Ashkenazi Jew from the West of the Russian Empire (now Poland). After some ten years of development, which Zamenhof spent translating literature into the language as well as writing original prose and verse, the first Esperanto grammar was published in Warsaw in July 1887. The number of speakers grew rapidly over the next few decades, at first primarily in the Russian empire and Eastern Europe, then in Western Europe and the Americas, China, and Japan. In the early years speakers of Esperanto kept in contact primarily through correspondence and periodicals, but in 1905 the first world congress of Esperanto speakers was held in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. Since then world congresses have been held in different countries every year, save for during the two World Wars, and have been attended by up to 6000 people (typically 2000-3000).

Esperanto has no official status in any country, but is an elective part of the curriculum in several state educational systems. There were plans at the beginning of the 20th century to establish Neutral Moresnet as the world's first Esperanto state, and the short-lived artificial island micronation of Rose Island used Esperanto as its official language in 1968. In China, there was talk in some circles after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution about officially replacing Chinese with Esperanto as a means to dramatically bring the country into the twentieth century, though this policy proved untenable. In the summer of 1924, the American Radio Relay League adopted Esperanto as its official international auxiliary language, and hoped that the language would be used by radio amateurs in international communications, but actual use of the language for radio communications was negligible. Esperanto is the working language of several non-profit international organizations such as the Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, but most others are specifically Esperanto organizations. The largest of these, the World Esperanto Association, has an official consultative relationship with the United Nations and UNESCO. The U.S. Army has published military phrasebooks in Esperanto, to be used in wargames by the enemy (i.e. non-U.S.) forces.

Linguistic properties

Classification

As a constructed language, Esperanto is not genealogically related to any ethnic language. Esperanto can be described as "a language lexically predominantly Romanic, morphologically intensively agglutinative and to a certain degree isolating in character". The phonology, grammar, vocabulary, and semantics are based on the western Indo-European languages. The phonemic inventory is essentially Slavic, as is much of the semantics, while the vocabulary derives primarily from the Romance languages, with a lesser contribution from Germanic. Pragmatics and other aspects of the language not specified by Zamenhof's original documents were influenced by the native languages of early speakers, primarily Russian, Polish, German, and French.

Typologically, Esperanto has prepositions and a pragmatic word order that by default is Subject Verb Object and Adjective Noun. New words are formed through extensive prefixing and suffixing.

Phonology

Main article: Esperanto phonologyEsperanto has 5 vowels and 23 consonants, of which two are semivowels. Tone is not used to distinguish meaning of words. Stress is always on the penultimate vowel, unless a final vowel o is elided (which in practice occurs mostly in poetry). For example, familio (family) is , but famili’ is .

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | g | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | x | h | ||||||

| Affricate | ʦ | ʧ | ʤ | |||||||||||

| Lateral approximant | l | |||||||||||||

| Approximant | w | j | ||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||

The sound /r/ is usually rolled, but may be tapped ( in the IPA). The /v/ has a normative pronunciation like an English v, but is sometimes somewhere between a v and a w (IPA ), depending on the language background of the speaker. A semivowel normally occurs only in diphthongs after the vowels /a/ and /e/. Common (if debated) assimilation includes the pronunciation of /nk/ as , as in English sink, and /kz/ as , like the x in English example.

A large number of possible consonant clusters can occur, up to three in initial position and four in medial position (for example, in instrui, to teach). Final clusters are uncommon except in foreign names, poetic elision of final o, and a very few basic words such as cent (hundred) and post (after).

Vowels

Esperanto has the five "pure" vowels of Classical Latin and Spanish. No distinctions of length are made and there are no nasalized vowels.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

There are six falling diphthongs: uj, oj, ej, aj, aŭ, eŭ (/ui̯, oi̯, ei̯, ai̯, au̯, eu̯/).

With only five vowels, a good deal of variation is tolerated. For instance, /e/ commonly ranges from (French é) to (French è). The details often depend on the speaker's native language. A glottal stop may occur between adjacent vowels in some people's speech, especially when the two vowels are the same, as in heroo (hero) and praavo (great-grandfather).

Grammar

Main article: Esperanto grammarEsperanto words are derived by stringing together prefixes, roots, and suffixes. This is very regular, so that people can create new words as they speak and be understood. Compound words are formed with modifier-first, head-final order, i.e. the same way as in English birdsong vs. songbird.

The different parts of speech are marked by their own suffixes: all common nouns end in -o, all adjectives in -a, all derived adverbs in -e, and all verbs end in one of six tense and mood suffixes, such as present tense -as.

Plural nouns end in -oj (pronounced "oy"), whereas direct objects end in -on. Plural direct objects end in -ojn (pronounced to rhyme with "coin"). Adjectives agree with their nouns; their endings are plural -aj (pronounced "eye"), direct-object -an, and plural direct-object -ajn (pronounced to rhyme with "fine").

|

|

The six verb inflections are three tenses and three moods. They are present tense -as, future tense -os, past tense -is, infinitive mood -i, conditional mood -us, and jussive mood -u. Verbs are not marked for person or number. For instance: kanti - to sing; mi kantas - I sing; mi kantis - I sang; mi kantos - I will sing.

|

|

Word order is comparatively free: adjectives may precede or follow nouns, and subjects, verbs and objects (marked by the suffix -n) can occur in any order. However, the article la (the) and the demonstratives almost always come before the noun, and a preposition must come before it. Similarly, the negative ne (not) and conjunctions such as kaj (both, and) and ke (that) must precede the phrase or clause they introduce. In copular (A = B) clauses, word order is just as important as it is in English clauses like people are dogs vs. dogs are people.

Vocabulary

Main article: Esperanto vocabularyThe core vocabulary of Esperanto was defined by Lingvo internacia, published by Zamenhof in 1887. It comprised 900 roots, which could be expanded into the tens of thousands of words with prefixes, suffixes, and compounding. In 1894, Zamenhof published the first Esperanto dictionary, Universala Vortaro, with a larger set of roots. However, the rules of the language allowed speakers to borrow new roots as needed, recommending only that they look for the most international forms, and then derive related meanings from these.

Since then, many words have been borrowed, primarily but not solely from the Western European languages. Not all proposed borrowings catch on, but many do, especially technical and scientific terms. Terms for everyday use, on the other hand, are more likely to be derived from existing roots—for example komputilo (a computer) from komputi (to compute) plus the suffix -ilo (tool)—or to be covered by extending the meanings of existing words (for example muso (a mouse), now also means a computer input device, as in English). There are frequent debates among Esperanto speakers about whether a particular borrowing is justified or whether the need can be met by deriving from or extending the meaning of existing words.

In addition to the root words and the rules for combining them, a learner of Esperanto must learn some idiomatic compounds that are not entirely straightforward. For example, eldoni, literally "to give out", is used for "to publish" (a calque of words in several European languages with the same derivation), and vortaro, literally "a collection of words", means "a glossary" or "a dictionary". Such forms are modeled after usage in some European languages, and speakers of other languages may find them illogical. Fossilized derivations inherited from Esperanto's source languages may be similarly obscure, such as the opaque connection the root word centralo "power station" has with centro "center". Compounds with -um- are overtly arbitrary, and must be learned individually, as -um- has no defined meaning. It turns dekstren "to the right" into dekstrumen "clockwise", and komuna "common/shared" into komunumo "community", for example.

Nevertheless, there are not nearly as many truly idiomatic or slang words in Esperanto as in ethnic languages, as these tend to make international communication difficult, working against Esperanto's main goal.

In modern times, conscious attempts have been made by Esperantists to eliminate perceived sexism in the language. One example of this is Riism, which is one among several propositions to modify the language in a non-sexist manner.

Writing system

Main article: Esperanto orthographyEsperanto is written with a modified version of the Latin alphabet, including six letters with diacritics: ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ and ŭ (that is, c, g, h, j, s circumflex, and u breve). The alphabet does not include the letters q, w, x, y except in unassimilated foreign names.

The 28-letter alphabet is:

All letters are pronounced approximately as their lower-case equivalents in the IPA, with the exception of c and the accented letters:

| Letter | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| c | |

| ĉ | |

| ĝ | |

| ĥ | |

| ĵ | |

| ŝ | |

| ŭ (as aŭ, eŭ) |

Three ASCII-compatible writing conventions are in use. These substitute digraphs for the accented letters. The original "h-convention" (ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, u) is based on English 'ch' and 'sh', while a more recent "x-convention" (cx, gx, hx, jx, sx, ux) is useful for alphabetic word sorting on a computer (cx comes correctly after cu, sx after sv, etc.) as well as for simple conversion back into the standard orthography. Finally, the insertion of an apostrophe as the second glyph (c', s', etc.) is also common. See Esperanta klavaro, keyboard layout, Latin-3 and Unicode.

Esperanto has been a 'clear' language for Morse code communication since the 1920s, and codes exist for all accented Esperanto characters.

Useful phrases

Here are some useful Esperanto phrases, with IPA transcriptions:

- Hello: Saluton /sa.ˈlu.ton/

- What is your name?: Kiel vi nomiĝas? /ˈki.el vi no.ˈmi.ʤas/

- My name is...: Mi nomiĝas... /mi no.ˈmi.ʤas/

- How much?: Kiom? /ˈki.om/

- Here you are: Jen /jen/

- Do you speak Esperanto?: Ĉu vi parolas Esperanton? /ˈʧu vi pa.ˈro.las es.pe.ˈran.ton/

- I don't understand you: Mi ne komprenas vin [mi ˈne kom.ˈpre.nas vin/

- I like this one: Mi ŝatas tiun ĉi /mi ˈʃa.tas ˈti.un ˈʧi/ or Ĉi tiu plaĉas al mi /ʧi ˈti.u ˈpla.ʧas al ˈmi/

- Thank you: Dankon /ˈdan.kon/

- You're welcome: Ne dankinde /ˈne dan.ˈkin.de/

- Please: Bonvolu /bon.ˈvo.lu/

- Here's to your health: Je via sano /je ˈvi.a ˈsa.no/

- Bless you!/Gesundheit!: Sanon! /ˈsa.non/

- Congratulations!: Gratulon! /ɡra.ˈtu.lon/

- Okay: Bone /ˈbo.ne/ or Ĝuste /ˈʤus.te/

- It is a nice day: Estas bela tago /ˈes.tas ˈbe.la ˈta.ɡo/

- I love you: Mi amas vin /mi ˈa.mas vin/

- Goodbye: Ĝis (la) (revido) /ʤis (la) (re.ˈvi.do)/

- I would like a beer, please: Unu bieron, mi petas. /ˈu.nu bi.ˈe.ron mi ˈpe.tas/

- What is that?: Kio estas tio? /ˈki.o ˈes.tas ˈti.o/

- That is... : Tio estas... /ˈti.o ˈes.tas/

- How are you?: Kiel vi (fartas)? /ˈki.el vi ˈfar.tas/

- Good morning!: Bonan matenon! /ˈbo.nan ma.ˈte.non/

- Good evening!: Bonan vesperon! /ˈbo.nan ves.ˈpe.ron/

- Good night!: Bonan nokton! /ˈbo.nan ˈnok.ton/

Sample text

Supporters of Esperanto argue that it is easy to pronounce and has a pleasant, harmonious sound not unlike Italian. Critics, on the other hand, point to the East European features of the language as being harsh and difficult to pronounce, and argue that Esperanto has an artificial feel to it, without the flow of a natural tongue. Both supporters and critics agree however, that the feel or 'flavour' of the language is an important factor in its success or failure. The following short extract gives an idea of the character of Esperanto:

- (Note: pronunciation is as per the section above. The main point for English speakers to note is that the letter 'J' in Esperanto has the same sound as the letter 'Y' in English)

"En multaj lokoj de Ĉinio estis temploj de drako-reĝo. Dum trosekeco oni preĝis en la temploj, ke la drako-reĝo donu pluvon al la homa mondo. Tiam drako estis simbolo de la supernatura estaĵo. Kaj pli poste, ĝi fariĝis prapatro de la plej altaj regantoj kaj simbolis la absolutan aŭtoritaton de feŭda imperiestro. La imperiestro pretendis, ke li estas filo de la drako. Ĉiuj liaj vivbezonaĵoj portis la nomon drako kaj estis ornamitaj per diversaj drakofiguroj. Nun ĉie en Ĉinio videblas drako-ornamentaĵoj kaj cirkulas legendoj pri drakoj."

- English Translation:

"In many places in China there were temples of the dragon king. During times of drought, people prayed in the temples, that the dragon king would give rain to the human world. At that time the dragon was a symbol of the supernatural. And later on, it became the ancestor of the highest royalty and symbolised the absolute authority of the feudal emperor. The emperor pretended that he was the son of the dragon. All of his personal possessions carried the dragon name and were decorated with different dragon figures. Now everywhere in China dragon decorations can be seen and dragon legends circulate."

The Esperanto speaker community

Geography and demography

Esperanto speakers are more numerous in Europe and East Asia than in the Americas, Africa, and Oceania, and more numerous in urban than in rural areas. Esperanto is particularly prevalent in the northern and eastern countries of Europe; in China, Korea, Japan, and Iran within Asia; in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico in the Americas; and in Togo and Madagascar in Africa.

An estimate of the number of Esperanto speakers was made by the late Sidney S. Culbert, a retired psychology professor of the University of Washington and a longtime Esperantist, who tracked down and tested Esperanto speakers in sample areas of dozens of countries over a period of twenty years. Culbert concluded that between one and two million people speak Esperanto at Foreign Service Level 3, "professionally proficient" (able to communicate moderately complex ideas without hesitation, and to follow speeches, radio broadcasts, etc.). Culbert's estimate was not made for Esperanto alone, but formed part of his listing of estimates for all languages of over 1 million speakers, published annually in the World Almanac and Book of Facts. Culbert's most detailed account of his methodology is found in a 1989 letter to David Wolff. Since Culbert never published detailed intermediate results for particular countries and regions, it is difficult to independently gauge the accuracy of his results.

In the Almanac, his estimates for numbers of language speakers were rounded to the nearest million, thus the number for Esperanto speakers is shown as 2 million. This latter figure appears in Ethnologue. Assuming that this figure is accurate, that means that about 0.03% of the world's population speaks the language. This falls short of Zamenhof's goal of a universal language, but it represents a level of popularity unmatched by any other constructed language. Ethnologue also states that there are 200 to 2000 native Esperanto speakers (denaskuloj), who have learned the language from birth from their Esperanto-speaking parents (this happens when Esperanto is the family language in an international family or sometimes in a family of devoted Esperantists).

Marcus Sikosek has challenged this figure of 1.6 million as exaggerated. Sikosek estimated that even if Esperanto speakers were evenly distributed, assuming one million Esperanto speakers worldwide would lead one to expect about 180 in the city of Cologne. Sikosek finds only 30 fluent speakers in that city, and similarly smaller than expected figures in several other places thought to have a larger-than-average concentration of Esperanto speakers. He also notes that there are a total of about 20,000 members of the various Esperanto organizations (other estimates are higher). Though there are undoubtedly many Esperanto speakers who are not members of any Esperanto organization, he thinks it unlikely that there are fifty times more speakers than organization members. Others think such a ratio between members of the organized Esperanto movement and speakers of the language is not unlikely.

The Finnish linguist Jouko Lindstedt, an expert on native-born Esperanto speakers, presented the following scheme to show the overall proportions of language capabilities within the Esperanto community:

- 1,000 have Esperanto as their native language

- 10,000 speak it fluently

- 100,000 can use it actively

- 1,000,000 understand a large amount passively

- 10,000,000 have studied it to some extent at some time.

In the absence of Dr. Culbert's detailed sampling data, or any other census data, it is impossible to state the number of speakers with certainty. Few observers, probably, would challenge the following statement from the website of the World Esperanto Association:

- Numbers of textbooks sold and membership of local societies put the number of people with some knowledge of the language in the hundreds of thousands and possibly millions.

Culture

Main articles: Esperanto culture, Esperanto literature, Esperanto film, and Esperanto musicEsperanto is often used to access an international culture, including a large corpus of original as well as translated literature. There are over 25,000 Esperanto books (originals and translations) as well as over a hundred regularly distributed Esperanto magazines. Many Esperanto speakers use the language for free travel throughout the world using the Pasporta Servo. Others like the idea of having pen pals in many countries around the world using services like the Esperanto Pen Pal Service. Every year, 1500-3000 Esperanto speakers meet for the World Congress of Esperanto (Universala Kongreso de Esperanto).

Historically most of the music published in Esperanto has been in various folk traditions; in recent decades more rock and other modern genres have appeared.

To some extent there are also shared traditions, like the Zamenhof Day, and shared behaviour patterns, like avoiding the usage of one's national language at Esperanto meetings unless there is good reason for its use.

Two full-length feature films have been produced with dialogue entirely in Esperanto, namely Angoroj in 1964 and Incubus starring William Shatner in 1965. Other amateur productions have been made, such as a dramatisation of the novel Gerda Malaperis (Gerda Has Disappeared). A number of "mainstream" films in national languages have used Esperanto in some way, such as Gattaca. In Charlie Chaplin's masterpiece The Great Dictator all of the signs in the Jewish Ghetto are in Esperanto.

Esperanto is frequently criticized for "having no culture". Proponents observe that Esperanto is culturally neutral by design, as it was intended to be a facilitator between cultures, not to be the carrier of any one culture. Thus it is considered a culture on its own. (See Esperanto as an international language.)

Science

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Nearly from the beginning Esperanto was used for scientific papers; the Fundamenta Krestomatio of 1903 contains a section El la vivo kaj sciencoj (from life and sciences). A few scientists, such as Maurice Fréchet, Helmar Frank and Reinhard Selten, have published part of their work in Esperanto. In articles on interlinguistics the use of Esperanto is common. It is not commonly used in Physics, Biology, or Chemistry.

Esperanto is the first language for teaching and administration of the International Academy of Sciences San Marino, which is sometimes called an "Esperanto University", although it does not teach the language, but in the language. It is not to be confused with the Akademio de Esperanto (Academy of Esperanto).

Goals of the Esperanto movement

Zamenhof's intention was to create an easy-to-learn language to foster international understanding. It was to serve as an international auxiliary language, that is, as a universal second language, not to replace ethnic languages. This goal was widely shared among Esperanto speakers in the early decades of the movement. Later, Esperanto speakers began to see the language and the culture that had grown up around it as ends in themselves, even if Esperanto is never adopted by the United Nations or other international organizations.

Those Esperanto speakers who want to see Esperanto adopted officially or on a large scale worldwide are commonly called finvenkistoj, from fina venko, meaning "final victory", or pracelistoj, from pracelo, meaning "original goal". Those who focus on the intrinsic value of the language are commonly called raŭmistoj, from Rauma, Finland, where a declaration on the near-term unlikelihood of the "fina venko" and the value of Esperanto culture was made at the International Youth Congress in 1980 (see Raumism). These categories are, however, not mutually exclusive. (See Finvenkismo)

The Prague Manifesto (1996) presents the views of the mainstream of the Esperanto movement and of its main organisation, the World Esperanto Association (UEA).

Symbols and flags

In 1893, C. Rjabinis and P. Deullin designed and manufactured a lapel pin for Esperantists to identify each other. The design was a circular pin with a white background and a five pointed green star. The theme of the design was the hope of the five continents being united by a common language.

The earliest flag, and the one most commonly used today, features a green five-pointed star against a white canton, upon a field of green. In 1905, delegates to the first conference of Esperantists at Boulogne-sur-Mer, unanimously approved a version, differing from the modern only by the superimposition of an "E" over the green star. Other variants include that for Christian Esperantists, with a white Christian cross superimposed upon the green star, and that for Leftists, with the color of the field changed from green to red.

In 1997, a second flag design was chosen in a contest by the UEA for the first centennial of the language. It featured a white background with two stylised curved "E"s facing each other. Dubbed the "jubilea simbolo" (jubilee symbol) , it attracted criticism from some Esperantists, who dubbed it the "melono" (melon) because of the design's elliptical shape. It is still in use, though to a lesser degree than the traditional symbol, known as the "verda stelo" (green star).

Esperanto and education

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Relatively few schools teach Esperanto officially outside of China, Hungary, and Bulgaria; the majority of Esperanto speakers continue to learn the language through self-directed study, online tutorials or correspondence courses. Several Esperanto paper correspondence courses were early on adapted to e-mail and taught by corps of volunteer instructors. In more recent years, teaching websites like lernu! have become popular. Various educators have estimated that Esperanto can be learned in anywhere from one quarter to one twentieth the amount of time required for other languages. Some argue, however, that this is only true for native speakers of Western European languages.

Claude Piron, a psychologist formerly at the University of Geneva and Chinese-English-Russian-Spanish translator for the United Nations, argued that Esperanto is far more "brain friendly" than many ethnic languages. "Esperanto relies entirely on innate reflexes differs from all other languages in that you can always trust your natural tendency to generalize patterns. The same neuropsychological law Jean Piaget generalizing assimilation — applies to word formation as well as to grammar."

Esperanto and language acquisition

Main article: Propaedeutic value of EsperantoSeveral research studies demonstrate that studying Esperanto before another foreign language speeds and improves learning the other language. This is presumably because learning subsequent foreign languages is easier than learning one's first, while the use of a grammatically simple and culturally flexible auxiliary language like Esperanto lessens the first-language learning hurdle. In one study, a group of European secondary school students studied Esperanto for one year, then French for three years, and ended up with a significantly better command of French than a control group, who studied French for all four years. Similar results were found when the second language was Japanese, or when the course of study was reduced to two years, of which six months was spent learning Esperanto.

Esperanto and religion

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Homaranismo

L. L. Zamenhof promoted a philosophy of his own called Homaranismo, but was concerned this could taint his earlier work in establishing Esperanto.

Oomoto

The Oomoto religion encourages the use of Esperanto among their followers and includes Zamenhof as one of its deified spirits.

Bahá'í

The Bahá'í Faith encourages the use of an auxiliary international language. While endorsing no specific language, some Bahá'ís see Esperanto as having great potential in this role.

Lidja Zamenhof, daughter of Esperanto's founder, became a Bahá'í.

Various volumes of the Bahá'í scriptures and other Baha'i books have been translated into Esperanto.

It should be noted that between 1979 and 1981 (the Bahá'í interest in Esperanto goes back over a century), the Islamic Republic of Iran through the mullahs had also encouraged the use of Esperanto.

Spiritism

Esperanto is also actively promoted, at least in Brazil, by followers of Spiritism. The Brazilian Spiritist Federation publishes Esperanto coursebooks, translations of Spiritism's basic books and encourages Spiritists to become Esperantists.

Bible translations

The first translation of the Bible into Esperanto was a translation of the Tanach or Old Testament done by L. L. Zamenhof. The translation was reviewed and compared with other languages' translations of the Bible by a group of British clergy and scholars before publishing it at the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1910. In 1926 this was published along with a New Testament translation, in an edition commonly called the "Londona Biblio". In the 1960s, Internacia Asocio de Bibliistoj kaj Orientalistoj tried to organize a new, ecumenical Esperanto Bible version. Since then, the Dutch Lutheran pastor Gerrit Berveling has translated the Deuterocanonical or apocryphal books in addition to new translations of the Gospels, some of the New Testament epistles, and some books of the Tanakh or Old Testament; these have been published in various separate booklets, or serialized in Dia Regno, but the Deuterocanonical books have appeared in recent editions of the Londona Biblio.

Christianity

- IKUE - Internacia Katolika Unuiĝo Esperantista - the International Union of Catholic Esperantists.

- Roman Catholic popes (including at least John Paul II and Benedict XVI) have occasionally used Esperanto in their multilingual urbi et orbi blessings.

- KELI - Kristana Esperantista Ligo Internacia - the International Christian Esperantists League. KELI was formed early in the history of Esperanto, and works in cooperation with IKUE

- An issue of "The Friend" describes the activities of the Quaker Esperanto Society.

- There are instances of Christian apologists and teachers who use Esperanto as a medium. Nigerian Pastor Bayo Afolaranmi's "Spirita nutraĵo" (spiritual food) Yahoo mailing list, for example, has hosted weekly messages since 2003.

- Chick Publications, publisher of Protestant fundamentalist themed evangelistic tracts, has published a number of comic book style tracts by Jack T. Chick translated into Esperanto, including "This Was Your Life!" ("Jen Via Tuto Vivo!")

Islam

Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran officially called on Muslims to learn Esperanto and praised the use of Esperanto as a medium for a better understanding among peoples of different religious backgrounds. He suggested Esperanto replace English as an International Lingua franca. Although Esperanto became popular in Iran well before his comment, it found its way to the seminaries of Qom following his verdict. An Esperanto translation of the holy Qur'an was shortly thereafter published by the state.

Nazism

In his work, Mein Kampf, Hitler mentioned Esperanto as an example of a language that could be used to achieve world dominance by an international Jewish Conspiracy. As a result, this led to the persecution of Esperantists during the Holocaust.

Criticism and modifications of Esperanto

Main articles: Esperanto as an international language and EsperantidoCommon criticisms of the language are that its vocabulary and grammar are too European; that its vocabulary, accented letters and grammar are not similar enough to major Western European languages (a critique addressed by Ido, Novial and Interlingua); that it is sexist; that it looks and sounds artificial; or that it has failed to meet the expectation - of at least its founder - that it would one day be seriously considered for use as a second language by all nations.

Though Esperanto itself has changed little since the publication of the Fundamento de Esperanto ("Foundation of Esperanto"), a number of reform projects have been proposed over the years, starting with Zamenhof's proposals in 1894 and Ido in 1907. Several later constructed languages, such as Fasile, were based on Esperanto.

In popular culture

Main article: Esperanto in popular cultureEsperanto has been used in a number of films and novels. Typically, this is done either to add the exoticness of a foreign language without representing any particular ethnicity, or to avoid going to the trouble of inventing a new language. The Charlie Chaplin film The Great Dictator (1940) showed shops designated in Esperanto, each with the general Esperanto suffix -ejo (meaning "place for..."), in order to convey the atmosphere of some 'foreign' East European country without reference to a particular East European language. The Canadian actor William Shatner learned Esperanto to a limited level so that he could star in the all-Esperanto B-movie horror film Incubus. In the British comedy Red Dwarf, Arnold Rimmer is seen attempting to learn Esperanto in a number of early episodes, including "Queeg". Esperanto can be overheard on the public address system in the US film "Gattaca."

See also

- Esperanto and Interlingua compared

- Esperanto as an international language

- Esperanto flag

- Esperantic Studies Foundation

- Monato (a monthly world news magazine)

References and notes

- Jouko Lindstedt (January 2006). "Native Esperanto as a Test Case for Natural Language" (pdf). University of Helsinki - Department of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - The Maneuver Enemy website

- Blank, Detlev (1985). Internationale Plansprachen. Eine Einführung ("International Planned Languages. An Introduction"). Akademie-Verlag. ISSN 0138-55 X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - Maire Mullarney Everyone's Own Language, p147, Nitobe Press, Channel Islands, 1999

- ^ Sikosek, Ziko M. Esperanto Sen Mitoj ("Esperanto without Myths"). Second edition. Antwerp: Flandra Esperanto-Ligo, 2003.

- Culbert, Sidney S. Three letters about his method for estimating the number of Esperanto speakers, scanned and HTMLized by David Wolff

- Lindstedt, Jouko. "Re: Kiom?" (posting). DENASK-L@helsinki.fi, 22 April 1996.

- Ziko van Dijk. Sed homoj kun homoj: Universalaj Kongresoj de Esperanto 1905–2005. Rotterdam: UEA, 2005.

- "Esperanto" by Mark Feeney. The Boston Globe, 12 May 1999

- "Kion Signifas Raŭmismo", by Giorgio Silfer.

- "Prague Manifesto" (English version). Universala Esperanto-Asocio, updated 2003-03-26.

- Piron, Claude: "The hidden perverse effect of the current system of international communication", published lecture notes

- Williams, N. (1965) 'A language teaching experiment', Canadian Modern Language Review 22.1: 26-28

- "The Baha'i Faith and Esperanto". Bahaa Esperanto-Ligo ( B.E.L. ). Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- "Esperanto - Have any governments opposed Esperanto?". Donald J. Harlow. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- "Uma só língua, uma só bandeira, um só pastor: Spiritism and Esperanto in Brazil by David Pardue" (PDF). University of Kansas Libraries. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- "La Sankta Biblio - "Londona text"". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- Eric Walker (May 27, 2005). "Esperanto Lives On". The Friend.

- Bayo Afolaranmi. "Spirita nutraĵo". Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- "Esperanto - Have any governments opposed Esperanto?". Donald J. Harlow. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- >"Esperanto in Iran (in Persian)". Porneniu. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- Adolph Hitler (1924). "Mein Kampf". Volume 1, Chapter XI. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

Further reading

- Emily van Someren. . Republication of the thesis 'The EU Language Regime, Lingual and Translational Problems'.

- Ludovikologia dokumentaro I Tokyo: Ludovikito, 1991. Facsimile reprints of the Unua Libro in Russian, Polish, French, German, English and Swedish, with the earliest Esperanto dictionaries for those languages.

- Fundamento de Esperanto. HTML reprint of 1905 Fundamento, from the Academy of Esperanto.

- Auld, William. La Fenomeno Esperanto ("The Esperanto Phenomenon"). Rotterdam: Universala Esperanto-Asocio, 1988.

- Butler, Montagu C. Step by Step in Esperanto. ELNA 1965/1991. ISBN 0-939785-01-3

- DeSoto, Clinton (1936). 200 Meters and Down. West Hartford, Connecticut, USA: American Radio Relay League, p. 92.

- Everson, Michael. Template:PDFlink. Evertype, 2001.

- Forster, Peter G. The Esperanto Movement. The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1982. ISBN 90-279-3399-5.

- Harlow, Don. The Esperanto Book. Self-published on the web (1995-96).

- Wells, John. Lingvistikaj aspektoj de Esperanto ("Linguistic aspects of Esperanto"). Second edition. Rotterdam: Universala Esperanto-Asocio, 1989.

- Zamenhof, Ludovic Lazarus, Dr. Esperanto's International Language: Introduction & Complete Grammar The original 1887 Unua Libro, English translation by Richard H. Geoghegan; HTML online version 2006. Print edition (2007) also available from ELNA or UEA.

External links

National Esperanto associations

- Ukrainia Ligo de Esperantista Junularo (Ukrainian Youth Association)

- Esperanto Association of Britain

- Junularo Esperantista Brita (British Youth Association)

- Canadian Esperanto Association

- New Zealand Esperanto Association

- Esperanto Association of Ireland

- Esperanto League for North America (USA)

- Australian Esperanto Association

- Melbourne Esperanto Association (Australia)

Information on Esperanto

- An Update on Esperanto by the World Esperanto Association

- Esperanto.net: information in many languages

- Esperanto: A Language for the Global Village by Sylvan Zaft

- A Key to the International Language compiled by R. Kent Jones and Christopher Zervic

- Blueprints for Babel: Esperanto - Commentary and grammatical summary of Esperanto and Riismo, with glossary and links

- "A Scottish Poet in Esperanto" by William Auld, Esperantist Nobel Prize nominee

- "Esperanto Studies: An Overview" by Humphrey Tonkin and Mark Fettes (1996)

- Articles on Esperanto and International communication (multilingual)

Esperanto courses and pronunciation

- Lernu.net – see also Lernu!

- Free Esperanto Course – E-mail correspondence course

- Kurso de Esperanto – Software and e-mail correspondence course (multilingual)

- Esperanto - Panorama

- Parolu, Esperanto pronunciation.

- Esperanto books at Project Gutenberg

Dictionaries

- Reta Vortaro, an Esperanto dictionary

- The Alternative Esperanto Dictionary, a dictionary of vulgarities and slang

- Esperanto Dictionary: from Webster's Dictionary

- Esperanto Wiktionary and Wiktionary:Category:Esperanto language

- jVortaro, an Esperanto dictionary written in Java

- Freelang Dictionary, a downloadable Esperanto-English dictionary

- , a downloadable Esperanto-English etymological dictionary by Andras Rajki

- Esperanto books at Project Gutenberg

Automatic translation from English and other languages

- Traduku: Online Machine Translator

- Esperantilo – Text editor with spell and grammar checking and machine translation from Esperanto to English, German and Polish

- From English to Esperanto

- Majstro Multlingva Tradukvortaro - A multilingual translation dictionary that uses Esperanto as a pivot language

- Logos

Input tools

- Esperanto Keyboard Layout – Esperanto IME.

- Melburno Notepad – Converts to Esperanto special characters - cx = ĉ, sx = ŝ etc.

- EK - Esperanta Klavaro (Esperanto Keyboard); type using x-convention and it will automatically convert special characters

- UniRed - A unicode plain text editor. Supports many charsets, has syntax coloring, search and replace via regular expressions. Able to run auxiliary programs, ISpell for example (for spellchecking). (project info: http://sourceforge.net/projects/unired)

News in Esperanto

- Libera Folio - Independent news site

- Raporto - Kie la mondo raportas al vi - news site

- Polish radio in Esperanto

- China Radio International

- TERRA-Esperanto expedition

- KLAKU social news site

Portals

- China Interreta Informa Centro - China's Official Gateway to News & Information in Esperanto

- Esperanto Pen Pal Service

- Google in Esperanto

- Ĝangalo - La mondo en Esperanto - The World in Esperanto (not updated at the moment)

- Startu.net

- -activities and resources for learning Esperanto.

Philosophy in Esperanto

- Enciklopedio Simpozio - All about philosophy in Esperanto

Entertainment

- Ĉi Tie Nun Podcast in Esperanto

- esPodkasto Rolfo's podcast

- Radio Verda Podcast of Arono and Karlina

International Esperanto organisations and institutions

Criticism

- Learn Not to Speak Esperanto by Justin B. Rye

- Esperanto - a critique by James Chandler

- "Why Esperanto is not my favourite Artificial Language"

- The irregularities of Esperanto from Mark Rosenfelder's Metaverse

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: