This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 98.199.232.188 (talk) at 17:47, 22 August 2008 (→Scientific positions: corrections made to a special plea by Michio Kaku). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:47, 22 August 2008 by 98.199.232.188 (talk) (→Scientific positions: corrections made to a special plea by Michio Kaku)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (June 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (August 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The cosmological argument is an argument for the existence of God or a "First Cause". It is traditionally known as an "argument from universal causation", an "argument from first cause", the "causal argument", and also as an "uncaused cause" or "unmoved mover" argument. Whichever term employed, there are three basic variants of the argument, each with subtle yet important distinctions: the arguments from causation, in esse and in fieri, and the argument from contingency.

History of the argument

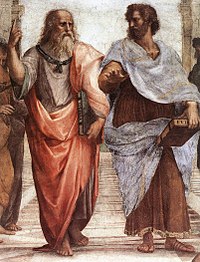

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) and Aristotle (c. 384–322 BCE) both posited first cause arguments, though each had certain notable caveats. Plato posited a basic argument in The Laws (Book X), in which he argued that motion in the world and the Cosmos was "imparted motion" that required some kind of "self-originated motion" to set it in motion and to maintain that motion. Plato also posited a "demiurge" of supreme wisdom and intelligence as the creator of the Cosmos in his work Timaeus. For Plato, the demiurge lacked the supernatural ability to create ex nihilo (out of nothing). It was only able to organize the ananke (necessity), the only other co-existent element or presence in Plato's cosmogony.

Aristotle also put forth the idea of a First Cause, often referred to as the "Prime Mover" or "Unmoved Mover" (Template:Polytonic or primus motor) in his work Metaphysics. For Aristotle too, as for Plato, the underlying essence of the Universe always was in existence and always would be (which in turn follows Parmenides' famous statement that "nothing can come from nothing"). Aristotle posited an underlying ousia (essence or substance) of which the Universe was composed, and it was this ousia that the Prime Mover organized and set into motion. The Prime Mover did not organize matter physically, but was instead a being who constantly thought about thinking itself, and who organized the Cosmos by making matter the object of "aspiration or desire". The Prime Mover was, to Aristotle, a "thinking on thinking", an eternal process of pure thought.

Centuries later, the Islamic philosopher Avicenna (c. 980-1037 CE) initiated a full-fledged inquiry into the question of being, in which he distinguished between essence (Mahiat) and existence (Wujud). He argued that the fact of existence could not be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves could not originate and interact with the movement of the Universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Thus, he reasoned that existence must be due to an agent cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. To do so, the cause must coexist with its effect and be an existing thing.

Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274 CE), probably the best-known theologian of Medieval Europe, adapted the argument he found in his reading of Aristotle and Avicenna to form one of the most influential versions of the cosmological argument. His conception of First Cause was the idea that the Universe must have been caused by something that was itself uncaused, which he asserted was God.

Many other philosophers and theologians have posited cosmological arguments both before and since Aquinas. The versions sampled in the following sections are representative of the most common derivations of the argument.

The argument

The cosmological argument could be stated as follows:

- Every finite and contingent being has a cause.

- Nothing finite and contingent can cause itself.

- A causal chain cannot be of infinite length.

- Therefore, a First Cause (or something that is not an effect) must exist.

According to the argument, the existence of the Universe requires an explanation, and the creation of the Universe by a First Cause, generally assumed to be God, is that explanation.

In light of the Big Bang theory, a stylized version of argument has emerged (sometimes called the Kalam cosmological argument, the following form of which was set forth by William Lane Craig):

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- The Universe began to exist.

- Therefore, the Universe had a cause.

A more detailed discussion of the argument

A basic explanation of the cosmological argument could be stated as follows:

- Consider some event in the Universe. No matter what event you choose, it will be the result of some cause, or, more likely, a very complex set of causes. Each of those causes is the result of some other set of causes, which are, in turn, the results of yet other causes. Thus, there is an enormous chain of events in the Universe, with the earlier events causing the latter. Either this chain has a beginning, or it does not.

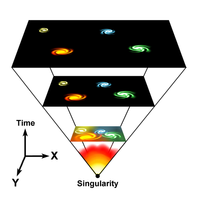

Currently, the theory of the cosmological history of the Universe most widely accepted by astronomers and astrophysicists today includes an apparent first event, the Big Bang, an expansion of all known matter and energy from an infinitely dense singularity at some finite time in the past. Although contemporary versions of the cosmological argument most typically assume that there was a beginning to the cosmic chain of physical or natural causes, the early formulations of the argument did not have the benefit of this degree of theoretical insight. The Big Bang theory, however, does not address the issue of the origin of the primordial singularity, so it does not address the issue of a First Cause in an absolute sense.

Plato's demiurge and Aristotle's Prime Mover each referred to a being who, they speculated, set in motion an already existing essence of the Cosmos. A millennium and a half later, Thomas Aquinas argued for an "Uncaused Cause" (ex motu), which he called God. To Aquinas, it remained logically possible that the Universe had already existed for an infinite amount of time and would continue to exist for an infinite amount of time. In his Summa Theologica, he argued that, even if the Universe had always existed (a notion he rejected on other grounds), there would still be the question of cause, or even of First Cause.

The argument from contingency

In the scholastic era, it was unknown whether the Universe had a beginning or whether it had always existed, at least in terms of that for which reason alone could account. As a matter of faith, the beginning of the world was believed by Christians. To account for both possibilities, Aquinas formulated the "argument from contingency", following Aristotle in claiming that there must be something to explain why the Universe exists. Since the Universe could, under different circumstances, conceivably not exist (contingency), its existence must have a cause - not merely another contingent thing, but something that exists by necessity (something that must exist in order for anything else to exist). In other words, even if the Universe has always existed, it still owes its existence to an Uncaused Cause, although Aquinas used the words "...and this we understand to be God."

Aquinas's argument from contingency is distinct from a first cause argument, since it assumes the possibility of a Universe that has no beginning in time. It is, rather, a form of argument from universal causation. Aquinas observed that, in nature, there were things with contingent existences. Since it is possible for such things not to exist, there must be some time at which these things did not in fact exist. Thus, according to Aquinas, there must have been a time when nothing existed. If this is so, there would exist nothing that could bring anything into existence. Contingent beings, therefore, are insufficient to account for the existence of contingent beings: there must exist a necessary being whose non-existence is an impossibility, and from which the existence of all contingent beings is derived.

The German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz made a similar argument with his principle of sufficient reason in 1714. "There can be found no fact that is true or existent, or any true proposition," he wrote, "without there being a sufficient reason for its being so and not otherwise, although we cannot know these reasons in most cases." He formulated the cosmological argument succinctly: "Why is there something rather than nothing? The sufficient reason is found in a substance which is a necessary being bearing the reason for its existence within itself."

Aristotelian philosopher Mortimer J. Adler devised a refined argument from contingency in his book How to Think About God:

- The existence of an effect requiring the concurrent existence and action of an efficient cause implies the existence and action of that cause.

- The Cosmos as a whole exists.

- The existence of the Cosmos as a whole is radically contingent (meaning that it needs an efficient cause of its continuing existence to preserve it in being, and prevent it from being annihilated, or reduced to nothing).

- If the Cosmos needs an efficient cause of its continuing existence, then that cause must be a supernatural being, supernatural in its action, and one the existence of which is uncaused, in other words, the Supreme Being, or God.

His premise for confirming all of these points was this:

The Universe as we know it today is not the only Universe that can ever exist in time. We can infer it from the fact that the arrangement and disarray, the order and disorder, of the present Cosmos might have been otherwise. That it might have been different from what it is. That which cannot be otherwise also cannot not exist; and conversely, what necessarily exists can not be otherwise than it is. Therefore, a Cosmos which can be otherwise is one that also cannot be; and conversely, a Cosmos that is capable of not existing at all is one that can be otherwise than it now is. Applying this insight to the fact that the existing Cosmos is merely one of a plurality of possible universes, we come to the conclusion that the Cosmos, radically contingent in existence, would not exist at all were its existence not caused. A merely possible Cosmos cannot be an uncaused Cosmos. A Cosmos that is radically contingent in existence, and needs a cause of that existence, needs a supernatural cause, one that exists and acts to exnihilate this merely possible Cosmos, thus preventing the realization of what is always possible for merely a possible Cosmos, namely, its absolute non-existence or reduction to nothingness.

Adler concludes that there exists a necessary being to preserve the Cosmos in existence. God must be there to sustain the Universe even if the Universe is eternal. Beginning by rejecting belief in a creating God, Adler finds evidence for a sustaining God. Thus, the existence of a sustaining God also becomes grounds for asserting the creating activity. The idea of a created Universe with a beginning an, most likely, an end now becomes more plausible than the idea of an eternal Universe. Adler believes that "to affirm that the world or Cosmos had an absolute beginning, that it was exnihilated at an initial instant, would be tantamount to affirming the existence of God, the world's exnihilator."

"In esse" and "in fieri"

The difference between the arguments from causation in fieri and in esse is a fairly important one. In fieri is generally translated as "becoming", while in esse is generally translated as "in existence". In fieri, the process of becoming, is similar to building a house. Once it is built, the builder walks away, and it stands on its own accord. (It may require occasional maintenance, but that is beyond the scope of the first cause argument.)

In esse (in existence) is more akin to the light from a candle or the liquid in a vessel. George Hayward Joyce, SJ, explained that "...where the light of the candle is dependent on the candle's continued existence, not only does a candle produce light in a room in the first instance, but its continued presence is necessary if the illumination is to continue. If it is removed, the light ceases. Again, a liquid receives its shape from the vessel in which it is contained; but were the pressure of the containing sides withdrawn, it would not retain its form for an instant." This form of the argument is far more difficult to separate from a purely first cause argument than is the example of the house's maintenance above, because here the First Cause is insufficient without the candle's or vessel's continued existence.

Thus, Aristotle's argument is in fieri, while Aquinas' argument is both in fieri and in esse (plus an additional argument from contingency). This distinction is an excellent example of the difference between a deistic view (Aristotle) and a theistic view (Aquinas). Leibnitz, who wrote more than two centuries before the Big Bang was taken for granted, was arguing in esse. As a general trend, the modern slants on the cosmological argument, including the Kalam argument, tend to lean very strongly towards an in fieri argument.

Objections and counterarguments

Existence of a First Cause

One possible objection to the argument was that it left open the question of why the First Cause was unique in that it did not require a cause. Proponents argue that the First Cause is exempt from having a cause, while opponents argue that it is not. The problem with arguing for the First Cause's exemption is that it begs the question of why the First Cause is indeed exempt. Attempts to resolve this problem often, though not necessarily, lead to ad hoc hypotheses and/or special pleading fallacies. However, the objection was illegitimate from the outset, because the Cosmological Argument does not attempt to show that the first cause is exempt from causation, but that any First Cause, by necessity, must be uncaused in order to be "first". The Cosmological Argument necessitates and proves a priori the existence of an Uncaused Cause. Therefore, if the Uncaused Cause is understood to be God, it is irrational to ask, "What causes God if He is the first cause?" Because the first cause, by definition, must have no cause. If this is understood, the argument is not a special plea.

Identity of a First Cause

Another objection is that even if one accepts the argument as a proof of a First Cause, it does not identify that First Cause with God. The argument does not ascribe to the First Cause some of the basic attributes commonly associated with, for instance, a theistic God, such as immanence or omnibenevolence. Rather, it simply argues that a First Cause must exist. Despite this, there exist theistic arguments that do extract such attributes.

Furthermore, if one chooses to accept God as the First Cause, God's continued interaction with the Universe is required. This is commonly known as the Contingency Argument, which proves that a thing is contingent upon some other thing with respect to its existence, and that this "other thing" is then contingent on something else. Based on the simutaneous nature of cause and effect, this is the foundation for the refutation of beliefs such as deism that accept that a God created the Universe, but then ceased to have any further interaction with it

Scientific positions

The argument for a Prime Mover is based on the scientific foundation of Newtonian physics and its earlier predecessors — the idea that a body at rest will remain at rest unless acted upon by an outside force. However, while Newton's ideas survive in physics today, since they conveniently and easily describe the movement of objects at the human (that is, not cosmic or atomic) level, they no longer represent the most accurate and truthful representations of the physical Universe. However, the Cosmological argument was designed solely for the purpose of explaining the cosmos from the human level, and thus is not affected by the above extrapolation.

Modern physics has many examples of bodies being moved without any moving body, apparently undermining the first premise of the Prime Mover argument: every object in motion must be moved by another object in motion. Physicist Michio Kaku directly addresses the cosmological argument in his book Hyperspace, claiming it might be dismissed by the law of conservation of energy and the laws governing molecular physics. He quotes one of many examples — "gas molecules may bounce against the walls of a container without requiring anything or anyone to get them moving." According to Kaku, these particles could move forever, without beginning or end. So, he supposes there is no need for a First Mover to explain the origins of motion. It does not provide an explanation for the reason those molecules exist in the first place, though. However, Boston University Professor, Peter Kreeft, argues that the Cosmological argument does not attempt to describe the microscopic universe. Thus, Michio Kaku's counter-arguments regarding the "laws governing molecular physics" are not applicable to the Cosmological Argument. Modern Quantum cosmology actually attempts to apply quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole, however it is rationally unsound to make extrapolations regarding the entire universe as a whole (an infinite knowledge wholly outside the range of human knowledge) in any sense, from data gathered inside of the finite range of human knowledge. Quantum mechanics likewise attempts to undermine the Argument from Contingency variant*. Quantum Determinism|indeterminancy implies that the principle of reason is simply incorrect; there is no reason for a quantum system to be in a particular quantum state, the choice of state is completely random. However, in the 1960 revised edition of Miracles, a book written by C.S. Lewis, a compelling case is made against the self-contradction of naturalism (and likewise of Quantum Physics), by which Lewis quotes J. B. S. Haldane in saying;

“ If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true ... and hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms. ” —J. B. S. Haldane, Possible Worlds, page 209

In this way, it is irrational, and scientifically unsound to cast aspersions on ones own ability to reason, and by extension, on ones ability to concieve such an idea as Quantum Mechanics in the first place. Furthermore, the very field of Quantum Mechanics has been subject to vicious criticism by many of the greatest minds and institutions in history such as Albert Einstein, and many Oxford University professors including C.S. Lewis and Alister McGrath. Consequently, opposing theories to quantum mechanics have come up such as continuum theories.

A variation of the Cosmological Argument, known as the Argument from Contingency, is not dependent on the consequential nature of causation however, by implying the simultaneousness of cause and effect, thus liberating the Cosmological argument of any constraints posed by the nature of time or sufficient reason. It does not seek to explain how a "thing in itself" (noumenon) is "because", but merely that it "is" in such a way as to be distinguishable from how it "seems" (phenomenon). Therefore it is not able to be refuted by any means available to the field of quantum mechanics. See Existentialism, Soren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Arguments in Islamic theology and philosophy

God as the First Cause

Main article: Kalam cosmological argumentAsh'ari theologians rejected cause and effect, in essence, but accepted it as something that facilitated humankind's investigation and comprehension of natural processes. These medieval scholars argued that Nature was composed of uniform atoms that were "recreated" at every instant by God. The laws of Nature were only the customary sequence of apparent causes (customs of God), the ultimate cause of each accident being God himself.

As argued by Avicenna, the Universe consists of a chain of actual beings, each giving existence to the one below it and responsible for the existence of the rest of the chain. Because an actual infinite is deemed impossible, this chain as a whole must terminate in a being that is wholly simple and one, whose essence is its very existence, and is therefore self-sufficient and not in need of something else to give it existence. Because its existence is not contingent on or necessitated by something else, but is necessary and eternal in itself, it satisfies the condition of being the necessitating cause of the entire chain that constitutes the eternal world of contingent existing things.

God as the Necessary Existent

The ontological form of the cosmological argument, which was put forward by Avicenna, is known as the contingency and necessity argument (Imakan wa Wujub).

Avicenna's proof for the existence of God, in the "Metaphysics" section of The Book of Healing, was the first ontological argument. This was the first attempt at using the method of a priori proof, which utilizes intuition and reason alone. Avicenna's proof is unique in that it can be classified as both a cosmological argument and an ontological argument. It is ontological insofar as "necessary existence" in intellect is the first basis for arguing for a Necessary Existent. The proof is also cosmological insofar as most of it is taken up with arguing that contingent existents cannot stand alone and must end in a Necessary Existent.

References

- "Cosmological Argument for the Existence of God", in Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1967), Vol. 2, p232 ff.

- "Cosmological Argument for the Existence of God", in Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1967), Vol. 2, p233 ff.

- ^ "Islam". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- Scott David Foutz, An Examination of Thomas Aquinas' Cosmological Arguments as found in the Five Ways, Quodlibet Online Journal of Christian Theology and Philosophy

- Craig, William L. "The Existence of God and the Beginning of the Universe." Truth Journal. Leadership University. 22 Jun. 2008 <http://www.leaderu.com/truth/3truth11.html>.

- Summa Theologiae, I : 2,3

- Aquinas was an ardent student of Aristotle's works, a significant number of which had only recently been translated into Latin by Ibn-Rushd, also known as Averroes.

- Summa Theologiae, I : 2,3

- Monadologie (1714). Nicholas Rescher, trans., 1991. The Monadology: An Edition for Students. Uni. of Pittsburg Press. Jonathan Bennett's translation. Latta's translation.

- Science in Christian Perspective

- Joyce, George Hayward (1922) Principles of Natural Theology. NY: Longmans Green.

- "deism." The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Answers.com 20 Jun. 2008. http://www.answers.com/topic/deism

- Robert G. Mourison (2002)

- Johnson (1984), pp. 161–171.

- Morewedge, P., "Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Malcolm and the Ontological Argument", Monist, 54: 234–49

- Mayer, Toby (2001), "Ibn Sina's 'Burhan Al-Siddiqin'", Journal of Islamic Studies, 12 (1), Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Oxford Journals, Oxford University Press: 18–39

See also

- Biblical cosmology

- Cosmogony

- Creation myth

- Dating Creation

- Determinism

- Infinitism

- Infinite regress

- Quinquae viae

- Temporal finitism

- Timeline of the Big Bang

- Unmoved mover

External links

- Bruce Reichenbach. "Cosmological Argument". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Articles on the cosmological argument by William Lane Craig

- Articles on the cosmological argument by Alexander Pruss

- Articles on the cosmological argument by Timothy O'Connor

- Articles on the atheistic cosmological argument by Quentin Smith and others

- A Reconstruction of the "Existential Argument" for the Existence of God by Stephen Pimentel

- A Scotistic Cosmological Argument Remixed by Josh Rasmussen

- A Cosmological Argument for a Self-Caused Universe by Quentin Smith