This is an old revision of this page, as edited by İnfoCan (talk | contribs) at 00:01, 7 December 2010. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:01, 7 December 2010 by İnfoCan (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Hatt-i Humayun (Turkish: Hatt-ı Hümâyun), also known as Hatt-i Sharif (Turkish: Hatt-ı Şerif) is the diplomatics term for a handwritten note of an official nature by the Ottoman Sultan. The terms come from Hatt (Arabic: handwriting, command), Hümayun ("imperial") and Şerif (lofty, noble). These notes were written by the Sultan himself, although they could also be transcribed by a palace scribe. They were written usually in response to, and directly on, a document that was submitted to him by the Grand Vizier or another officer of the Sublime Porte. Thus, they could be approvals or denials on a letter of petition, acknowledgements of a report, grants of permission for a request, an annotation to a decree, etc. Other types of hatt-ı hümayuns were written from scratch, rather than as a response.

Hatt-ı Hümayun is also the commonly known name of the Reform Decree of 1856 that initiated the Tanzimat reform.

Types of hatt-ı hümayun

The hatt-ı humayun would usually be written to the Grand Vizier (Sadrazam), sometimes to his aid (the Kaymakam), or to another senior official such as the Kaptan-ı Derya or the Beylerbey of Rumeli. There were three types of hatt-ı hümayuns: 1) those addressed to a (government) position, 2) those "on the white" and 3) those on a document.

Hatt-ı hümayun to the rank

Most decrees (ferman) or titles of provilege (berat) were written by a scribe, but those written to a particular official and that were particularly important were preceded by the Sultan's handwritten note beside his seal (Tughra), emphasizing a particular part of his edict, urging or ordering it to be followed without fault. These were called Hatt-ı Hümayunla Müveşşeh Ferman (ferman decorated with a hatt-ı hümayun) or Unvanına Hatt-ı Hümayun (Hatt-ı hümayun to the position). There might be a clichéed phrase like "to be done as required" (mûcebince amel oluna) or "no one is to be interfered with to execute my command as required" ('emrim mûcebince amel oluna, kimseye müdahale etmeyeler'). Some edicts to the rank would start with a praise for the person(s) the edict was addressed to, in order to encourage or honor him. Rarely, there might be threats such as "if you need your head do it as required" (Başın gerek ise mûcebiyle amel oluna).

Hatt-ı hümayun on the white

"Hatt-ı hümayun on the white" ('beyaz üzerine hatt-ı hümâyun') were documents written from scratch (ex officio) rather than a notation on an existing document. They were so called because the edict was written on a clear page. They could be documents such as a command, an edict, an appointment letter or a letter to a foreign ruler.

There also exist hatt-ı hümayuns expressing the Sultan's opinions or even his feelings on certain matters. For example, after the succesful defense of Mosul against the forces of Nadir Shah, in 1743, the Sultan sent a hatt-ı hümayun to the governor Haj Husayn Pasha, which praised in verse the heroic expoits of the governor and the warriors of Mosul.

Hatt-ı hümayun on documents

In normal procedure, a document usually submitted by the Grand Vizier, or his aid the kaymakam (kâimmakam pasha), would summarize a situation and request the Sultan's will on the matter. Such documents were called telhis (summary) until the 19th century, and takrir (suggestion) later on. The Sultan's handwritten response (command or decision) would be called hatt-ı hümâyûn on telhis (or, on takrir). Other types of documents submitted to the Sultan were petitions (arzuhâl), sworn transcriptions of oral petitions (mahzar), reports from a higher to a lower office (şukka), religious reports by Qadis to higher offices (ilâm) and record books (tahrirat). These would be named hatt-ı hümâyûn on arz, etc. depending on the type of the document. The Sultan responded not only to documents submitted to him by his viziers but also to petitions (arzuhâl) submitted to him by the common people following the Friday prayer. Thus, hatt-ı hümayuns on documents were analogous to Papal rescripts and rescripts used in other imperial regimes.

In some cases the Grand Vizier would append his cover page on top of a proposal coming from a lower-level functionary (like a Defterdar or a Serasker), introducing it as, for example, "this is the proposal of the Defterdar". In such cases the Sultan would write his hatt-ı hümayun on the cover page. In other cases the Grand Vizier would summarize the matter directly in the margin of the document submitted by the lower functionary and the Sultan would write on the same page as well. Sometimes the Sultan would write his decision on a fresh piece of paper attached to the submitted document.

Examples

-

Command of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II to his Grand Vizier regarding maintaining dams in Istanbul to relieve the misery of his subjects during a drought.

Command of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II to his Grand Vizier regarding maintaining dams in Istanbul to relieve the misery of his subjects during a drought.

-

Response (ca. 1788) of Selim III on a memorandum regarding printing "İslâmbol" instead of "Kostantiniye" on new coins: "My Deputy Grand Vizier! My imperial decree has been that, if not contrary to current law, the word of Konstantiniye is not to be printed."

Response (ca. 1788) of Selim III on a memorandum regarding printing "İslâmbol" instead of "Kostantiniye" on new coins: "My Deputy Grand Vizier! My imperial decree has been that, if not contrary to current law, the word of Konstantiniye is not to be printed."

-

Upon note that the Minbar to be sent to Medina requires 134 kantars of copper, Sultan responds on the top, in his own handwriting, "be it given."

Upon note that the Minbar to be sent to Medina requires 134 kantars of copper, Sultan responds on the top, in his own handwriting, "be it given."

-

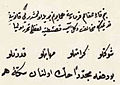

Note by Sultan Murad IV (in thick script on top) on the appointment document of Vizier Suleiman Pasha to the post of Beylerbey of Rumeli: "Be it done as required."

Note by Sultan Murad IV (in thick script on top) on the appointment document of Vizier Suleiman Pasha to the post of Beylerbey of Rumeli: "Be it done as required."

-

Response to the request for permission from the Maritime Ministry to start building 6 gunboats using this year's emergency funds, for the protection of the coasts, if the submitted drawings are approved. Sultan Abdulhamid II responds (on the left page) in his own handwriting, "modify drawing and resubmit it so the ship's bow resembles that of a cruiser"

Response to the request for permission from the Maritime Ministry to start building 6 gunboats using this year's emergency funds, for the protection of the coasts, if the submitted drawings are approved. Sultan Abdulhamid II responds (on the left page) in his own handwriting, "modify drawing and resubmit it so the ship's bow resembles that of a cruiser"

-

A personal correspondence between Ahmed III and his Grand Vizier. "My Vizier. Today where do you intend to go? How is my girl, the piece of my life? Make me happy with the health of your holy disposition. My body is in good health, thank be God. Those of my imperial family are in good health as well. Let me know when you know."

A personal correspondence between Ahmed III and his Grand Vizier. "My Vizier. Today where do you intend to go? How is my girl, the piece of my life? Make me happy with the health of your holy disposition. My body is in good health, thank be God. Those of my imperial family are in good health as well. Let me know when you know."

Language

The language of hatt-ı hümayuns on documents generally used relatively simple Turkish that is understandable even today and has changed little over the centuries. The Sultan would usually start with "It has become my knowledge" (Malumum oldu), and sometime start with an introduction on the topic, then give his opinion such as "this report's appearance and meaning has become my imperial knowledge.("... işbu takrîrin/telhîsin/şukkanın/kaimenin manzur ve me'azi ma'lum-ı hümayunum olmuşdur"). Some common phrases in hatt-ı hümayuns are "according to this report..." (işbu telhisin mûcebince), "the matter is clear" (cümlesi malumdur), "I permit" (izin verdim), "I give, according to the provided facts" (vech-i meşruh üzere verdim).

He would refer to his Grand Vizier as "My Vizier", or if his Grand Vizier was away at war, would refer to his locum tenens as "Ka'immakâm Paşa". Other officials would be referred to by their names, such as "You who are my Vizier of Rumeli, Mehmed Pasha" ("Sen ki Rumili vezîrim Mehmed Paşa'sın"). Notes without an address were meant for the Grand Vizier or the kâ'immakam.

History

Until the reign of Murad III, Viziers would present matters orally to the Sultan, who would then give his consent or denial, also orally. While hatt-ı hümayuns were very rare until then, they proliferated afterwards, especially during the reigns of Sultans such as Abdülhamid I, Selim III and Mahmud II, who wanted to increase their control and be informed of everything.

The earliest known hatt-ı hümayun is the one sent by Sultan Murad I to Evrenos Bey in 1386.

The early hatt-ı hümayuns were written in the calligraphic styles of tâlik, tâlik kırması (a varian of tâlik), nesih and riq’a. After Mahmud II, they were only written in riq’a.

Ahmed III and Mahmud II were skilled penmen and their hatt-ı hümayuns are notable for their long and elaborate annotations on official documents. In contrast, Sultans who accessed the throne at an early age, such as Murad V and Mehmed IV are known for their poor spelling and calligraphy.

After the Tanzimat, the government bureaucracy was streamlined. For most common communications, the imperial scribe (Serkâtib-i şehriyârî) began to record the will (irade) of the Sultan and thus the irâde (also called irâde-i seniyye, i.e., "supreme will", or irâde-i şâhâne, i.e., "glorious will" ) replaced the hatt-ı hümayun. The use of hatt-ı hümayuns on the white between the Sultan and the Grand Vizier continued on for matters of great importance.

The large number of documents that required the Sultan's decision through either a hatt-ı hümayun or an irade-i senniye indicate how centralized the Ottoman governemt was. Abdülhamid I has written himself in one of his hatt-ı hümayuns "I have no time that my pen leaves my hand, with God's resolve it does not leave my hand.

Archival

Hattı hümayuns sent to the Grand vizier were handled and recorded by the Âmedi Kalemi, ("office for incoming documents") of the Grand Vizier. The Âmedi Kalemi organized and recorded in all correspondence between the Grand Vizier and the Sultan, as well as correspondence with foreign rulers and Ottoman ambassadors. Other hatt-ı hümayuns not addressed to the Grand Vizier were stored in other document stores (called fon in the terminology of current Turkish archivists). Hatt-ı hümayuns began to be cataloged in 1883 and there are four historic catalogs of them:

Hatt-ı Hümâyûn Tasnifi is the catalog of the hatt-ı hümayuns belonging to the Amedi Kalemi. It consists of 31 volumes listing 62,312 documents, with their short summaries. This catalog lists documents from 1730 to 1839 but cover primarily those from the reigns of Selim III and Mahmud II within this period.

'Ali Emiri Tasnifi is chronological catalog on 181,239 documents is organized according to the periods of sovereignty of sltans, from the foundation of the Ottoman state to Abdülmecid period. Along with hatt-ı hümayuns, it includes documents on foreign relations.

İbnülemin Tasnifi is a catalog crated by a committee lead by historian İbnülemin Mahmud Kemal. It covers the years l290-l873. Along with 329 hatt-ı hümayuns, it lists documents of various other types on palace correspondence, private correspondance, appointments, timar and zeamet, vakıf, etc.

Muallim Cevdet Tasnifi catalogs 216,572 documents in 34 volumes are organized by topics that include local governments, provincial administration, vakıf and internal security.

Today all hatt-ı hümayuns have been recorded in a computerized database in the Ottoman Archives of the Turkish Prime Minister (Başbakanlık Osmalı Arşivleri, or BOA in short) in Istanbul, and their number is 95,134. Most hatt-ı hümayuns are stored at the BOA and in the Topkapı Museum Archive. The BOA contains 58,000 hatt-ı hümayuns.

During the creation of the State Archives in the 19th century, a separate storage area was created containing all hatt-ı hümayuns on the white and, in the process, handwritten notes of the Sultan were cut out of the documents for storage in the same place. This may have been intended as a sign of respect toward the Sultan, but it resulted in a terrible loss of information for historians in terms of what document each hatt-i hümayun was responding to. As a result, today the Ottoman Archives has a special section of "cut-out hatt-ı hümayuns". Another problem with the cataloging of hatt-ı hümayuns is that most of them are undated.

The Hatt-ı Hümâyun of 1856

Main article: Hatt-ı Hümayun

Although there exist thousands of Hatt-ı Hümayuns, the Hatt-ı Hümayun of 1856 (or Islâhat Fermânı) of 1856 is so well known as to be called simply "Hatt-ı Hümâyûn" in most history texts. The decree from Sultan Abdülmecid I promised equality in education, government appointments, and administration of justice to all, regardless of creed. In Düstur, the Ottoman official gazette, the text of this ferman is introduced as "a copy of the supreme ferman written to the Grand Vizier, perfected by decoration above with a hatt-ı hümayun.", so technically this edict was a hatt-i hümayun to the rank.

Another name used in some sources for the Reform Decree of 1856, is "The Rescript of Reform", This is a misnomer because a rescript is a document written in response to another document.

The Hatt-ı Hümayun of 1856 was an extension of another important edict of reform, the Hatt-i Sharif of Gülhane of 1839, and part of the Tanzimat reforms. That document is also generally referred to as the Hatt-i Sharif, although there are many other hatt-i sharifs.

References

- ^ Hüseyin Özdemir (2009). "Hatt-ı Humayın". Sızıntı (in Turkish) (365): 230. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|archive=(help); Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Bekir Koç (2000). "Hatt-ı Hümâyunların Diplomatik Özellikleri ve Padişahı bilgilendirme Sürecindeki Yerleri" (PDF). OTAM, Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi (in Turkish) (11): 305-313.

- Denis Sinor (1996). Uralic And Altaic Series, Volumes 1-150. Psychology Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780700703807.

- ^ Osman Köksal. "Osmanlı Hukukunda Bir Ceza Olarak Sürgün ve İki Osmanlı Sultanının Sürgünle İlgili Hattı-ı Hümayunları" (PDF) (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- Yücel Özkaya. "III. Selim'in İmparatorluk Hakkındaki Bazı Hatt-ı Hümayunları" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Text "language-Turkish" ignored (help) - ^ "Hatt-ı Hümâyun" (in Turkish).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accesdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Hüseyin Özdemir (2009). "Hatt-ı Humayın". Sızıntı. p. 230. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

Benim bir vaktim yokdur ki kalem elimden düşmez. Vallâhü'l-azîm elimden düşmez.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - Mehmet Seyitdanlıoğlu (2009). "19.Yüzyıl Türkiye Yönetim Tarihi kaynakları: Bir Bibliyografya Denemesi". 19.Yüzyıl Türkiye Yönetim Tarihi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- "Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi Rehberi" (PDF). T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- "Başbakanlık archives" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- "Hazine-i Evrakın Kurulması" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- "Islahata dair taraf-ı Vekâlet-i mutlakaya hitaben balası hatt-ı hümayun ile müveşşeh şerefsadır olan ferman-ı âlinin suretidir". Düstur (Istanbul: Matbaa-i Âmire) (in Turkish). 1856.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - See footnote 4 in: Edhem Eldem. "Ottoman Financial Integration with Europe: Foreign Loans, the Ottoman Bank and the Ottoman Public Debt" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- "Rescript of Reform – Islahat Fermanı (18 February 1856)". Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- "Ottoman Empire". Retrieved 2010-12-05.