This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tóraí (talk | contribs) at 09:05, 28 May 2012 (→Multilateral relations: rm confusing use of language). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:05, 28 May 2012 by Tóraí (talk | contribs) (→Multilateral relations: rm confusing use of language)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Ireland–United Kingdom relations" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| |

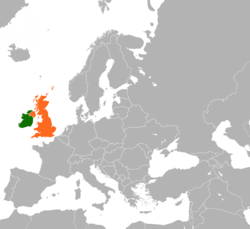

Ireland |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (May 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

British–Irish relations, or Anglo-Irish relations, refers to the relationship between the Government of Ireland (including the Government of the Irish Free State) and the Government of the United Kingdom since most of Ireland gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1922 as the Irish Free State.

Relations between the two states have been influenced heavily by issues arising from the independence of the Irish Free State and the government of Northern Ireland. These include the outbreak of political violence in Northern Ireland in 1968 and a desire for and resistance to the reunification of Ireland arising from the partition of Ireland in the 1920s. As well as these issues, the high level of trade between the two states, their comparable geographic location as islands off the coast of the European mainland, a long shared history and close cultural and linguistic links, as well as a shared land border, mean political developments in both states often closely follow each other or are tied in some way.

A Common Travel Area exists between the two states (including the dependencies of the UK in the region) and citizens of both state are accorded the same privileges in each other's jurisdiction (with minor exceptions). Two bodies, the British–Irish Council and the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly, co-ordinate political discussion between the two states (including devolved regions in the UK and the three dependencies of the UK in the region) on matters of mutual interest. Two further trans-national bodies relate specifically to relations between the British and Irish states with respect to Northern Ireland: the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and the North/South Ministerial Council.

Both sovereign states joined the European Union (then the European Communities) in 1973. However, the three dependencies of the UK in the region remain outside of the EU.

Background

Due to their proximity, there have been relations between the people inhabiting the islands of Ireland and Great Britain for as much as we know of their history. A Romano-Briton, Patricius, later known as Saint Patrick, brought Christianity Ireland and, following the fall of the Roman Empire, missionaries from Ireland re-introduced Christianity to Britain.

The expansion of Gaelic culture into what became known as Scotland (after the Latin Scoti, meaning Gaels) brought close political and familial ties between people in Ireland and people in Great Britain, lasting from the early Middle Ages to the 17th century, including a common Gaelic language spoken on both islands. The Norman invasion of Ireland, subsequent to the Norman conquest of England, added political ties between Ireland and England, including a common English language.

Over the course of the second millennium AD, the degree of influence and control the English exercised in Ireland fluctuated, while Irish influence in Scotland eventually collapsed. After initially covering over two thirds of the island of Ireland at the end of the 12th century, the area under English control reduced rapidly during the 14th century to the Pale, an area around the city of Dublin. However, the Tudor conquest, wars and programmes of colonisation of the 16th and 17th centuries brought Ireland securely under English control. However, this was at a cost of great resentment over land ownership and inequitable laws. This resulted in Gaelic ties between Scotland and Ireland withering dramatically over the course of the 17th century, including a divergence in the Gaelic language into two distinct languages.

Secret societies, both opposing and supporting British rule through violent means, developed in the 18th century and several open rebellions were staged, most notably the 1798 Rebellion. Although Ireland gained near-independence from Great Britain in 1782, the kingdoms of Ireland and the Great Britain (which was formed from the kingdoms of England and Scotland) were merged in 1801 to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Although many were content with being a part of the United Kingdom, both violent and constitutional campaigns for autonomy or independence from Britain throughout the 19th century led to the granting of autonomy to Ireland (and the "temporary" partition of the island) in 1914. However, the outbreak of World War I delayed its implementation. During the course of the war, a rebellion in 1916 and the government response to it led to demands for full independence. An election in 1918 returned almost 70% of seats to the pro-independence party Sinn Féin. The Sinn Féin candidates returned refused to take their seats in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, set up a parliament in Dublin, and declared the independence of Ireland from the United Kingdom. A war of independence followed that ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922, the establishment of the Irish Free State and an ensuing Irish Civil War.

Post-independence

Immediate issues arising from Irish independence and partition of the island were the settlement of an agreed border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, and the amount of public debt of the United Kingdom for which the Irish Free State would assume responsibility. In response to the first of these issues a commission, the Boundary Commission, was set up involving representatives from the Government of the Irish Free State, the Government of Northern Ireland, and the Government of the United Kingdom which would chair the Commission.

Disagreements over the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty led the Irish government to a view that the Boundary Commission was only intended to award areas within the six counties of Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State. The British government's view was that the border was adjustable in either direction so long as the net balance would benefit the Free State. In the mean time, three years after independence, the Irish government had not yet contributed anything to paying the public debt of the United Kingdom. The report of the Commission was leaked by the press causing embarrassment to the Irish government and spurring protests from both nationalists and unionists in Northern Ireland. Eager to avoid conflict, and with other concerns on their mind, the three parties agreed to bury the report, with the agreement that the border would change little, the Irish government would be relieved of their obligation to servicing the UK's public debt and the Council of Ireland, a mechanism agreed to in the 1922 Treaty to re-unify Ireland by 1970, was abolished.

A further dispute arose in 1930 over the issue of the Irish government's refusal to reimburse the United Kingdom with "land annuities". These annuities were derived from government financed soft loans given to Irish tenant farmers before independence to allow them to buy out their farms from landlords (see Irish Land Acts). These loans were intended to redress the issue of landownership in Ireland arising from the wars of the 17th century. The refusal of the Irish government to pass on monies it collected from these loans to the British government led to a retaliatory and escalating trade war between the two states from 1932 until 1938, a period known as the Anglo-Irish Trade War or the Economic War.

While the UK was less affected by the Economic War, the Irish economy was virtually crippled and the resulting capital flight reduced much of the economy to a state of barter. Unemployment was extremely high and the effects of the Great Depression compounded the difficulties. The government urged people to support the confrontation with the UK as a national hardship to be shared by every citizen. Pressures, especially from agricultural producers in Ireland and exporters in the UK, led to an agreement between the two governments in 1938 resolving the dispute.

Under the terms of resulting Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, all duties imposed during the previous five years were lifted but Ireland was still entitled to impose tariffs on British imports to protect new Irish industries. Ireland was to pay a one-off £10 million sum to the United Kingdom (as opposed to annual repayments of £250,000 over 47 more years). Arguably the most significant outcome, however, was the return of so-called "Treaty Ports", three ports in Ireland maintained by the UK as sovereign bases under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The return of these ports facilitated Irish neutrality during World War II.

Ireland's sudden unilateral declaration of a republic by removing the remaining duties of the king in 1949 did not result in greatly strained relations. However, it drew a response from the UK government that meant the UK would not grant Northern Ireland to the Irish state without the consent of the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Ireland chose to formally leave the British Commonwealth at that time, although it had ceased to attend meetings since 1937.

World War II

Northern Ireland

From 1937 until 1998, the Constitution of Ireland made a territorial claim on Northern Ireland, which is internationally recognised as part of the United Kingdom. This was dropped as part of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which set in place a series of bodies.

Post-1998 (Good Friday Agreement)

For a long time, many Irish people had sought some sort of recognition from the British government for the immense loss of life in Ireland during the Famine caused by the policy of the then British government in increasing Irish food exports to Britain while many of the population starved to death or emigrated. When Tony Blair became the British prime minister, he apologised to the Irish people, in an effort to progress the British–Irish relationship to the next stage. The next stage would eventually lead to the Good Friday Agreement, bringing hopes of a lasting peace in Northern Ireland and the amelioration of British–Irish relations, with the setting up of the British–Irish Council and North/South Ministerial Council.

An estimated 24% or 14 million Britons claim Irish descent.

Meetings of the British Prime Minister and the Irish Taoiseach are generally referred to as Anglo-Irish Summits.

Queen Elizabeth II made a state visit to the Republic of Ireland on 17–20 May 2011. She was the first British monarch to visit the Republic. One hundred years earlier, as part of his accession tour, her grandfather, King George V, visited Ireland on 8–12 July 1911, when it was still part of the United Kingdom. The Queen's visit was welcomed by the Irish government political parties of Fine Gael and Labour, as well as by Fianna Fáil. Parties such as Sinn Féin, Éirígí, the Workers' Party, the Socialist Party, People Before Profit Alliance, the Socialist Workers Party and the Communist Party opposed the visit.

Co-operation

Intergovernmental bodies

The following is a summary of the intergovernmental bodies in between Ireland, the United Kingdom and its constituent countries, and the Crown dependencies. This list does not include bodies that exist solely in the United Kingdom.

| Organisation | Purpose | Members |

|---|---|---|

| British-Irish Council | A forum form multilateral cooperation on areas of joint interest | Ireland, United Kingdom, Scotland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Wales, Northern Ireland |

| British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly | Foster understanding between parliamentarians | Ireland, United Kingdom, Scotland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Wales, Northern Ireland |

| British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference | Bilateral cooperation, especially on non-devolved policy areas for Northern Ireland | Ireland, United Kingdom, Northern Ireland |

| North-South Ministerial Council | Whole-island cooperation for Ireland | Ireland, Northern Ireland |

| Ireland Wales Programme | Implements EU regional development projects | Ireland, Wales, European Union |

Multilateral relations

Aside from the two sovereign states of the United Kingdom and Ireland, the UK is additionally composed of four constituent parts: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Devolved administrations exist in three of these: Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Additionally, the British Crown has three dependencies: the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey.

The main institutional forum for multilateral relations in the UK, its constituent parts and dependencies in the region, and Ireland is the British–Irish Council. The British-Irish Council (BIC) is an international organisation established under the Belfast Agreement in 1998. Its membership comprises representatives from:

- the two sovereign governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom;

- the three devolved administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales

- the crown dependencies of Guernsey, the Isle of Man and Jersey.

The Council formally came into being on 2 December 1999. Its stated aim is to "promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands". The BIC has a standing secretariat, located in Edinburgh, Scotland, and meets in bi-annual summit session and regular ministerial meetings.

Some researchers have compared the British-Irish council to similar multilateral bodies amongst the Nordic countries: the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers.

In addition to the council, there is also the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA), a deliberative body consisting of members of legislative bodies in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the British crown dependencies. Its purpose is to foster common understanding between elected representatives from these jurisdictions.

The assembly consists of members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Oireachtas (the Irish parliament) as well as five representatives from the Scottish Parliament, five from the National Assembly for Wales, five from the Northern Ireland Assembly, and one each from the States of Jersey, the States of Guernsey and the Tynwald of the Isle of Man.

Bilateral relations

Numerous bilateral relations exist between the various countries in the archipelago, including between Ireland and the devolved governments of the United Kingdom. One important body is the North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) a body established under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland. The Council takes the form of meetings between ministers from both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and is responsible for twelve policy areas. Six of these areas are the responsibility of corresponding North/South Implementation Bodies.

The Republic of Ireland has also established bilateral relations with three countries of the Crown dependencies: the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey.

Ireland has also established bilateral relationships with Wales and Scotland. The Irish and Welsh government are collaborating on various economic development projects through the auspices of the Ireland Wales Programme, funded by the European Union.

Joint projects

A number of large-scale joint projects amongst the various countries in the Isles have been undertaken, often around infrastructure and energy. For example, the governments of Ireland, Scotland, and Northern Ireland are collaborating on the ISLES project, which will facilitate the development of offshore renewable energy sources, such as wind, wave and tidal energy, and renewable energy trade between Scotland, Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Through the auspices of the British-Irish council, Ministers from all countries have agreed to work on energy cooperation

Isle of Man and Ireland are also planning the development of renewable energy sources, including sharing costs for the development of a wind farm off the coast of the Isle of Man. Sources indicate a wider collaboration is also planned, with Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, and Ireland, to leverage the strong tidal currents around the Channel Islands.

An intergovernmental collaboration platform called the Irish Sea Region has also been set up, managed by the Dublin regional authority. The platform links the governments of Ireland, Isle of Man, the UK, and various local jurisdictions, in order to collaborate on planning for development of the Irish sea and bordering areas.

In 2004, a natural gas interconnection agreement was signed, linking Ireland with Scotland via the Isle of Man.

Common travel area

Various multilateral arrangements over the years have led to the development of the Common Travel Area, a passport-free zone that comprises the islands of Ireland, Great Britain, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The area's internal borders are subject to minimal or non-existent border controls and can normally be crossed by Irish and British citizens with only minimal identity documents,

Citizenship and citizens rights

Due to the close historical connections between the isles, a number of special citizenship and voting rules apply. For example, Irish citizens resident in the UK can vote and stand in any UK elections; UK citizens resident in Ireland can vote or stand in European and Local Elections, vote in parliamentary elections, but not vote or stand in Presidential elections or referendums.

Political movements

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2012) |

An important political movement in several countries in the Isles is British unionism, an ideology favoring the continued union of the United Kingdom. It is most prevalent in Scotland, England, and Northern Ireland. British unionism has close ties to British nationalism. Another movement is Loyalism, which manifests itself as loyalism to the British Crown.

The converse of unionism, Nationalism, is also an important factor for politics in the Isles. Nationalism can take the form of Welsh nationalism, Cornish_nationalism, English nationalism, Scottish nationalism, Ulster nationalism, or independence movements in the Isle of Man or Channel Islands.

Pan-Celticism is also a movement which is present in several of the countries which have a celtic heritage.

There are no major political parties that are present in all of the countries, but several Irish parties such as Sinn Fein and Fianna Fail have won elections in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and both of these parties have established offices in Britain in order to raise funds and win additional supporters.

Immigration and emigration

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2012) |

Irish migration to Great Britain is an important factor in the politics and labor markets of the Isles. Irish people have been the largest minority group in Britain for centuries, regularly migrating across the Irish Sea. From the earliest recorded history to the present, there has been a continuous movement of people between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain due to their proximity. This tide has ebbed and flowed in response to politics, economics and social conditions of both places. As of the 2011 census, there were 869,000 Irish-born residents in the United Kingdom.

Culture

Main article: British_Isles § CultureMany of the countries and regions of the isles, especially Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, Isle of Man, and Scotland share a common Celtic heritage, and all of these countries have branches of the Celtic league.

Some sports are organized on an All-Islands basis, such as rugby. The Triple Crown is an honour contested annually by the four national teams of the British Isles who compete within the larger Six Nations Championship: England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. If any one of those four teams wins all its games against the other three, they win the Triple Crown.

Academic perspectives

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (May 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The recent trend of using an archipelago perspective in scholarship of history, politics and identity in relations between Britain and Ireland was initiated by historian J. G. A. Pocock in the 1970s. He pressed his fellow historians to reconsider two issues linked to the future of British and Irish history. First, he urged historians of the Britain and Ireland to move away from histories of the Three Kingdoms (Scotland, Ireland, England) as separate entities, and he called for studies implementing a bringing-together or conflation of these national narratives into truly integrated enterprises. Pocock proposed the term Atlantic archipelago to avoid the contested British Isles. It has since become the commonplace preference of historians to treat British history in just this fashion (e.g. Hugh Kearney's The British Isles: A History of Four Nations or Norman Davies The Isles: A History).

In recent times, Richard Kearney has been an important scholar in this space, through his works for example on a "Postnationalist Archipelago". While Kearney's work has been noted by many as important for understanding of modern Irish politics and identity, some have also argued that his approach can be applied to the archipelago as a whole:

"Scholars and critics have noted the importance of Kearney's work on post-nationalism for Irish studies and politics. However, less attention has been paid to its implications for discussions and debates beyond the Irish Sea. In this context, Kearney's writings can be viewed as part of a broader intellectual landscape in which national identity, nationalism, and possibly postnationalism are at the center of political and intellectual discussions in the Isles. I say the Isles here, rather than simply Britain, because re-imagining the component parts of Britain, or more precisely the United Kingdom, entails reconfiguring the relationships in the entire archipelago."

Kearney's ideas and thinking were important in the lead-up to the Good Friday Agreement, and he was an early proponent of what eventually became the British-Irish Council.

The University of Exeter in the UK and the Moore Institute at the National University of Ireland, Galway started in October 2010 the Atlantic Archipelago Research Project, which purports to "take an interdisciplinary view on how Britain’s post-devolution state inflects the formation of post-split Welsh, Scottish and English identities in the context of Ireland’s own experience of partition and self-rule; Consider the significance of this island grouping to the understanding of a Europe that exists in a range of configurations; from large scale political union, to provinces, dependencies, and micro-nationalist regions (such as Cornwall), each with their contribution and presence; Reconsider relations across our island grouping in light of issues regarding the management and use of the environment."

References

- "One in four Britons claim Irish roots". BBC News. 16 March 2001. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "Queen to make first state visit to Irish Republic". BBC News. 4 March 2011.

- The royal family leaving Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) by carriage (1911) RTÉ Libraries and Archives. Retrieved: 2011-05-17.

- The Visit to Ireland Medal 1911 - 2011 The Royal Irish Constabulary Forum. Retrieved: 2011-05-17.

- How George V was received by the Irish in 1911 The Daily Telegraph 2011-11-10.

-

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - Jesse, Neal G., Williams, Kristen P.: Identity and institutions: conflict reduction in divided societies.Publisher: SUNY Press, 2005, page 107. ISBN 0-7914-6451-2

- "Scottish government website"

- Qvortrup, M and Hazell, R (1998). "The British-Irish Council: Nordic Lessons for the Council of the Isles" (Document). University College London.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "North-South Ministerial Council: 2010 Yeirlie Din" (PDF). Armagh: North/South Ministerial Council. 2010.

- "Ireland Wales Programme 2007 - 2013". Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- McWilliams, Patrick (18 May 2011). Irish-Scottish Links on Energy Study (ISLES) (PDF). All Energy 2011. Scottish Government. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Andrew Woodcock (20 June 2011). "'ALL-ISLANDS' ENERGY PLAN AGREED". Press Association National Newswire.

- "Isle of Man to share wind farm cost with Ireland?". Isleofman.com. 21 June 2011.

- "British Isles deal on channel Islands Renewable Energy". Indiainfoline News Service. 3 August 2011.

- "Irish Sea Region". Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Agreement relating to the Transmission of Natural Gas through a Second Pipeline between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland and through a Connection to the Isle of Man" (Document). 24 September 2004.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - "Common Travel Area between Ireland and the United Kingdom". Citizens Information Board. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- "Ministers 'must prepare for Jersey independence'". This is Jersey. 21st January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Political parties to build links with Irish in Britain". The Irish Post. 17 February 2012.

- Census home: Office for National Statistics

- Pocock, The Discovery of Islands, 77–93.

- Pocock, "British History: a Plea for a New Subject," 22–43 (1975); "The Field Enlarged: an Introduction," 47–57; and "The Politics of the New British History," 289–300, in The Discovery of Islands. See also "The Limits and Divisions of British History: in Search of the Unknown Subject," American Historical Review 87:2 (Apr. 1982), 311–36; "The New British History in Atlantic Perspective: an Antipodean Commentary," American Historical Review 104:2 (Apr. 1999), 490–500.

- Kearney, Richard (2006). "Chapter 1: Towards a Postnationalist Archipelago". Navigations: Collected Irish Essays, 1976-2006. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815631262.

- Peter Gratton, John Panteleimon Manoussakis, Richard Kearney (2007). Peter Gratton, John Panteleimon Manoussakis (ed.). Traversing the Imaginary: Richard Kearney and the Postmodern Challenge. Northwestern University studies in phenomenology & existential philosophy. Northwestern University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780810123786.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Atlantic Archipelagos Research Project (AARP)".

See also

- Anglo-Irish

- Irish community in Britain

- Politics in the British Isles

- Queen Elizabeth II's visit to the Republic of Ireland

| Africa |  | |

|---|---|---|

| Americas | ||

| Asia | ||

| Europe | ||

| Oceania | ||

| Former | ||

| Multilateral relations | ||

| Diplomatic missions | ||

| British Isles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||||||

| History (outline) |

| ||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||