This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Yahoo12123 (talk | contribs) at 00:03, 16 July 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:03, 16 July 2012 by Yahoo12123 (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)of Brittany|

| Hundred Years' War Lancastrian phase (1415–1453) | |

|---|---|

|

Background

Simultaneously, the Black Prince The final phase of warmaking that ] Henry V, who was finally given the opportunity. In 1414, Henry turned down an Armagnac offer to restore the Brétigny frontiers in return for his support. Instead, he demanded a return to the territorial status during the reign of Henry II. In August 1415, he landed with an army at Harfleur and took it, although the city resisted for longer than expected. This meant that by the time he came to marching farther, most of the campaign season was gone. Although tempted to march on Paris directly, he elected to make a raiding expedition across France toward English-occupied Calais. In a campaign reminiscent of Crécy, he found himself outmanoeuvred and low on supplies, and had to make a stand against a much larger French army at the Battle of Agincourt, north of the Somme. In spite of his disadvantages, his victory was near-total; the French defeat was catastrophic, with the loss of many of the Armagnac leaders. About 40% of the French nobility was lost at Agincourt.

Henry took much of Normandy, including Caen in 1417 and Rouen on January 19, 1419, making Normandy English for the first time in two centuries. He made formal alliance with the Duchy of Burgundy, who had taken Paris, after the assassination of Duke John the Fearless in 1419. In 1420, Henry met with the mad king Charles VI, who signed the Treaty of Troyes, by which Henry would marry Charles' daughter Catherine and Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France. The Dauphin, Charles VII, was declared illegitimate. Henry formally entered Paris later that year and the agreement was ratified by the Estates-General.

Henry's progress was now stopped by the arrival in France of a Scottish army of around 6,000 men. In 1421, a combined Franco-Scottish force led by John Stewart, Earl of Buchan crushed a larger English army at the Battle of Bauge, killing the English commander, Thomas, 1st Duke of Clarence, and killing or capturing most of the English leaders. The French were so grateful that Buchan was immediately promoted to the office of High Constable of France. Soon after the Battle of Bauge Henry V died at Meaux in 1422. Soon after that, Charles too had died. Henry's infant son, Henry VI, was immediately crowned king of England and France, but the Armagnacs remained loyal to Charles' son and the war continued in central France.

The English continued to attack France and in 1429 were besieging the important French city of Orleans. An attack on an English supply convoy led to the skirmish that is now known as Battle of the Herrings when John Fastolf circled his supply wagons (largely filled with herring) around his archers and repelled a few hundred attackers. Later that year, a French saviour appeared in the form of a peasant girl from Domremy named Joan of Arc.

French victory: 1429–1453

By 1424, the uncles of Henry VI had begun to quarrel over the infant's regency, and one, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, married Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, and invaded Holland to regain her former dominions, bringing him into direct conflict with Philip III, Duke of Burgundy.

By 1428, the English were ready to pursue the war again, laying siege to Orléans. Their force was insufficient to fully invest the city, but larger French forces remained passive. In 1429, Joan of Arc convinced the Dauphin to send her to the siege, saying she had received visions from God telling her to drive out the English. She raised the morale of the local troops and they attacked the English Redoubts, forcing the English to lift the siege. Inspired by Joan, the French took several English strong points on the Loire. Shortly afterwards, a French army, some 8000 strong, broke through English archers at Patay with 1500 heavy cavalry, defeating a 3000-strong army commanded by John Fastolf and John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury. This victory opened the way for the Dauphin to march to Reims for his coronation as Charles VII.

After Joan was captured by the Burgundians in 1430 and later sold to the English, tried by an ecclesiastic court, and executed, the French advance stalled in negotiations. But, in 1435, the Burgundians under Philip III switched sides, signing the Treaty of Arras and returning Paris to the King of France. Burgundy's allegiance remained fickle, but their focus on expanding their domains into the Low Countries left them little energy to intervene in France. The long truces that marked the war also gave Charles time to reorganise his army and government, replacing his feudal levies with a more modern professional army that could put its superior numbers to good use, and centralising the French state.

A repetition of Du Guesclin's battle avoidance strategy paid dividends and the French were able to recover town after town.

By 1449, the French had retaken Rouen, and in 1450 the Count of Clermont and Arthur de Richemont, Earl of Richmond, of the Montfort family (the future Arthur III, Duke of Brittany) caught an English army attempting to relieve Caen at the Battle of Formigny and defeated it, the English army having been attacked from the flank and rear by Richemont's force just as they were on the verge of beating Clermont's army. The French proceeded to capture Caen on July 6 and Bordeaux and Bayonne in 1451. The attempt by Talbot to retake Gascony, though initially welcomed by the locals, was crushed by Jean Bureau and his cannon at the Battle of Castillon in 1453 where Talbot had led a small Anglo-Gascon force in a frontal attack on an entrenched camp. This is considered the last battle of the Hundred Years' War.

Significance

The Hundred Years' War was a time of military evolution. Weapons, tactics, army structure, and the societal meaning of war all changed, partly in response to the demands of the war, partly through advancement in technology, and partly through lessons that warfare taught.

Before the Hundred Years' War, heavy cavalry was considered the most powerful unit in an army, but by the war's end, this belief had shifted. The heavy horse was increasingly negated by the use of the longbow (and, later, another long-distance weapon: firearms) and fixed defensive positions of men-at-arms — tactics which helped lead to English victories at Crécy and Agincourt. Learning from the Scots, the English began using lightly armoured mounted troops — later called dragoons — who would dismount in order to fight battles. By the end of the Hundred Years' War, this meant a fading of the expensively outfitted, highly trained heavy cavalry, and the eventual end of the armoured knight as a military force and the nobility as a political one.

The war also stimulated nationalistic sentiment. It devastated France as a land, but it also awakened French nationalism. The Hundred Years' War accelerated the process of transforming France from a feudal monarchy to a centralised state. The conflict became one of not just English and French kings but one between the English and French peoples. There were constant rumours in England that the French meant to invade and destroy the English language. National feeling that emerged out of such rumours unified both France and England further. The Hundred Years War basically confirmed the fall of the French language in England, which had served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce there from the time of the Norman conquest until 1362.

Timeline

Battles

Further information: List of Hundred Years' War battlesImportant figures

| King Edward III | 1327–1377 | Edward II's son |

| King Richard II | 1377–1399 | Edward III's grandson |

| King Henry IV | 1399–1413 | Edward III's grandson |

| King Henry V | 1413–1422 | Henry IV's son |

| King Henry VI | 1422–1461 | Henry V's son |

| Edward, the Black Prince | 1330–1376 | Edward III's son |

| John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster | 1340–1399 | Edward III's son |

| John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford | 1389–1435 | Henry IV's son |

| Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster | 1306–1361 | Knight |

| John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury | 1384–1453 | Knight |

| Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York | 1411–1460 | Knight |

| Sir John Fastolf | 1378?–1459 | Knight |

| King Philip VI | 1328–1350 | |

| King John II | 1350–1364 | Philip VI's son |

| King Charles V | 1364–1380 | John II's son |

| Louis I of Anjou | 1380–1382 | John II's son |

| King Charles VI | 1380–1422 | Charles V's son |

| King Charles VII | 1422–1461 | Charles VI's son |

| Joan of Arc | 1412–1431 | Commander |

| Jean de Dunois | 1403–1468 | Knight |

| Gilles de Rais | 1404–1440 | Knight |

| Bertrand du Guesclin | 1320–1380 | Knight |

| Jean Bureau | 13??–1463 | Knight |

| La Hire | 1390–1443 | Knight |

| Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy | 1363–1404 | Son of John II of France |

| John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy | 1404–1419 | Son of Philip the Bold |

| Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy | 1419–1467 | Son of John the Fearless |

Memory and impact

Lowe (1997) argues that opposition to the war helped to shape England's early modern political culture. Although anti-war and pro-peace spokesmen generally failed to influence outcomes at the time, they had a long-term impact. England showed decreasing enthusiasm for a conflict deemed not in the national interest, yielding only losses in return for the economic burdens it imposed. In comparing this English cost-benefit analysis with French attitudes, given that both countries suffered from weak leaders and undisciplined soldiers, Lowe notes that the French understood that warfare was necessary to expel the foreigners occupying their homeland. Furthermore French kings found alternative ways to finance the war - sales taxes, debasing the coinage - and were less dependent than the English on tax levies passed by national legislatures. English anti-war critics thus had more to work with than the French.

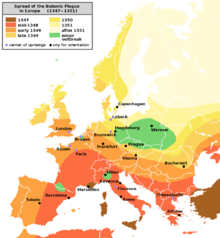

Bubonic Plague and warfare depleted the overall population of Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries. France, for example, had a population of about 17 million, which by the end of the Hundred Years War had declined by about one-half. Some regions were affected much more than others. Normandy lost three-quarters of its population during the war. In the Paris region, the population between 1328 and 1470 was reduced by at least two-thirds.

See also

- Timeline of the Hundred Years' War

- French military history

- British military history

- Anglo-French relations

- Medieval demography

- Second Hundred Years' War- this is the name given by some historians to the near-continuous series of conflicts between Britain and France from 1688–1815, beginning with the Glorious Revolution and ending with the Battle of Waterloo.

References

- ^ Peter Turchin (2003). "Historical dynamics: why states rise and fall". Princeton University Press. pp.179–180. ISBN 0-691-11669-5

- Preston, Richard (1991). Men in arms: a history of warfare and its interrelationships with Western society. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-033428-4.

- French as a mother-tongue in Medieval England

- Ben Lowe, Imagining Peace: A History of Early English Pacifist Ideas, 1340-1560 (1997)

- Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie (1987). "The French peasantry, 1450-1660". University of California Press. p.32. ISBN 0-520-05523-3

Bibliography

Primary sources

- The Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333-1381. Edited by V.H. Galbraith. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1927.

- Avesbury, Robert of. De gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi Tertii. Edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. London: Rolls Series, 1889.

- Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Eugene Deprez and Jules Viard. Paris: Honore Champion, 1977.

- Dene, William of. Historia Roffensis. British Library, London.

- French Chronicle of London. Edited by G.J. Aungier. Camden Series XXVIII, 1844.

- Froissart, Jean. Chronicles. Edited and translated by Geoffrey Brereton. London: Penguin Books, 1978.

- Gesta Henrici Quinti: The Deeds of Henry V. Translated by Frank Taylor and John S. Roshell. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1975.

- Grandes chroniques de France. Edited by Jules Viard. Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1920-53.

- Gray, Sir Thomas. Scalacronica. Edited and Translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell. Edinburgh: Maclehose, 1907.

- Le Baker, Geoffrey. Chronicles in English Historical Documents. Edited by David C Douglas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Le Bel, Jean. Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Jules Viard and Eugène Déprez. Paris: Société de l'historie de France, 1904.

- Register of Edward the Black prince, vol. 1. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1930.

- Rotuli Parliamentorum. Edited by J. Strachey et al., 6 vols. London: 1767-83.

- St. Omers Chronicle. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, MS 693, fos. 248-279v. (Edited and translated into English by Clifford J. Rogers)

- The Chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet. Translated by Thomas Johnes. London, 1840.

Anthologies of primary sources

- Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince. Edited and Translated by Richard Barber. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997.

- Original Letters Illustrative of English History. Edited by Sir Henry Ellis, Third Series Vol. 1. London: S&J Bentley, 1846.

- The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations. Edited by Anne Curry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000.

- The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Edited and Translated by Clifford J. Rogers. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

Secondary sources

- Allmand, Christopher, The Hundred Years War: England and France at War, c.1300-c.1450, Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-521-31923-4

- Arms, Armies and Fortifications in the Hundred Years War. Edited by Anne Curry and Michael Hughes. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

- Barber, Richard. Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine: A Biography of the Black Prince. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003.

- Barker, Juliet R. Agincourt: Henry V and the Battle that Made England. New York, NY: Little, Brown, and Co, 2006.

- Barnies, John. War in Medieval English Society: Social Values in the Hundred Years War 1337-99. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971.

- Bell, Adrian R., War and the Soldier in the Fourteenth Century, The Boydell Press, November 2004, ISBN 1-84383-103-1

- Braudel, Fernand, The Perspective of the World, Vol III of Civilization and Capitalism 1984 (in French 1979).

- Burne, Alfred Higgins. The Agincourt War: A Military History of the Latter Part of the Hundred Years’ War, from 1369 to 1453. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1976.

- Contamine, Philippe. La France au XIVe et XVe siècles Hommes, mentalities, guerre et paix. London: Variorum Reprints, 1981.

- Coss, Peter. The Knight in Medieval England 1000-1400. Dover, NH: Alan Sutton Publishing Inc., 1993.

- Crane, Susan. The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity During the Hundred Years War (2002) excerpt and text search

- Curry, Anne, The Hundred Years War, Macmillan Press, (2nd ed. 2003)

- Curry, Anne. Agincourt: A New History. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus, 2005.

- Duby, Georges. France in the Middle Ages 987-1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc. Translated by Juliet Vale. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1991.

- Dunnigan, James F., and Albert A. Nofi. Medieval Life & The Hundred Years War, Online Book.

- Favier, Jean. La Guerre de Cent Ans. Fayard, 1980.

- France in the Later Middle Ages 1200-1500. Edited by David Potter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Green, David. The Battle of Poitiers, 1356 (2002). ISBN 0-7524-1989-7.

- Inscribing the Hundred Years’ War in French and English Cultures. Edited by Denise N. Bakes. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000.

- Hoskins, Peter. In the Steps of the Black Prince, The Road to Poitiers, 1355-1356. Boydell&Brewer, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84383-611-7.

- Jones, Michael. Between France and England: Politics, Power and Society in Late Medieval Brittany. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2003.

- Keegan, John. The Face of Battle (1976), covers the battle of Agincourt, comparing it to modern battles

- Keen, M.H. The Laws of War in the Late Middle Ages. London: Routledge & Paul Kegan Ltd., 1965.

- Knecht, Robert J. The Valois: Kings of France 1328-1589. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

- Lewis, P.S. Essays in Later Medieval French History. London: The Hambledon Press, 1985.

- Lucas, Henry Stephen. The Low Countries and the Hundred Years’ War, 1326-1347. Philadelphia: Porcupine Press, 1976.

- Neillands, Robin, The Hundred Years War, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 978-0-415-26131-9

- Nicolle, David, and Angus McBride. French Armies of the Hundred Years War: 1328-1429 (2000) Men-At-Arms Series, 337 excerpt and text search

- Perroy, Edouard, The Hundred Years War, Capricorn Books, 1965.

- Reid, Peter. Medieval Warfare: Triumph and Domination in the Wars of the Middle Ages. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007.

- Rogers, Clifford J. "The Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years War," The Journal of Military History 57 (1993): 241-78. in Project Muse

- Rogers, Clifford J. War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327-1360. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000.

- Ross, Charles, The Wars of the Roses, Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Seward, Desmond, The Hundred Years War. The English in France 1337–1453, Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 0-14-028361-7 excerpt and text search.

- Society at War: The Experience of England and France During the Hundred Years War. Edited by C.T. Allmand. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1973.

- Soldiers, Nobles, and Gentlemen: Essays in Honour of Maurice Keen. Edited by Peter Coss and Christopher Tyerman. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009.

- Stone, John. "Technology, Society, and the Infantry Revolution of the Fourteenth Century," The Journal of Military History 68.2 (2004) 361-380 in Project Muse

- Sumption, Jonathan, The Hundred Years War I: Trial by Battle, University of Pennsylvania Press, September 1999, ISBN 0-8122-1655-5

- Sumption, Jonathan, The Hundred Years War II: Trial by Fire, University of Pennsylvania Press, October 2001, ISBN 0-8122-1801-9

- Sumption, Jonathan, The Hundred Years War III: Divided Houses, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-8122-4223-2

- The Age of Edward III. Edited by J.S. Bothwell. York: York Medieval Press, 2001.

- The Battle of Crecy 1346. Edited by Andrew Ayton and Sir Philip Preston. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007.

- The Hundred Years War. Edited by Kenneth Fowler. Macmillan, London 1971.

- Vale, Malcolm. The Angevin Legacy and the Hundred Years War, 1250-1340. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd., 1990.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew, and Donald J. Kagay, eds. The Hundred Years War: A Wider Focus (2005) online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Wagner, John A., Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, August 2006. ISBN 0-313-32736-X

- War, Government and Power in Late Medieval France. Edited by Christopher Allmand. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000.

- Waugh, Scott L. England in the Reign of Edward III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Wright, Nicholas. Knights and Peasants: The Hundred Years War in the French Countryside. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1998.