This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dume7 (talk | contribs) at 15:09, 27 May 2006 (→Mental breakdown and death (1889 - 1900)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:09, 27 May 2006 by Dume7 (talk | contribs) (→Mental breakdown and death (1889 - 1900))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche | |

|---|---|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy, Weimar Classicism; Precursor to Existentialism, Postmodernism, Poststructuralism, Psychoanalysis |

| Main interests | Aesthetics, Epistemology, Ethics, Ontology |

| Notable ideas | Apollonian-Dionysian Duality, Eternal Recurrence, Will to Power, Herd instinct, Overman, The Death of God, Master-Slave Morality |

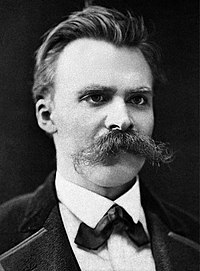

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (IPA:) (October 15, 1844 – August 25, 1900), a German philologist and philosopher, produced critiques of contemporary culture, religion, and philosophy centered around a basic question regarding the positive and negative attitudes toward life of various systems of morality. Beyond the unique themes dealt with in his works, Nietzsche's powerful style and subtle approach distinguish his writings. Although largely overlooked during his short yet astonishingly productive working life, which ended with a mental collapse at the age of 44, Nietzsche received recognition during the second half of the 20th century as a highly significant figure in modern philosophy.

Life

Youth (1844 - 1869)

Friedrich Nietzsche was born on October 15 1844, in the small town of Röcken, near Leipzig, in the then Prussian province of Saxony. His name comes from King Frederick William IV of Prussia, who celebrated his 49th birthday on the day of Nietzsche's birth. Nietzsche's parents were Carl Ludwig (1813-1849), a Lutheran pastor and former teacher, and Franziska (1826-1897). His sister, Elisabeth, was born in 1846, followed by his brother Ludwig Joseph in 1848. After the death of their father in 1849 and the young brother in 1850, the family moved to Naumburg, where they lived with his maternal grandmother and his father's two unmarried sisters under the (formal) guardianship of a local magistrate, Bernhard Dächsel. After the death of Nietzsche's grandmother in 1856 the family could afford their own house. During this time, the young Nietzsche attended a boys' school and later a private school, where he became friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from respected families. In 1854, he began to attend the Domgymnasium in Naumburg, but after he showed particular talents in music and language, the internationally recognized Schulpforta admitted him as a pupil, and there he continued his studies from 1858 to 1864. Here he became friends with Paul Deussen and Carl von Gersdorff. He also found time to work on poems and musical compositions. At Schulpforta, Nietzsche received an important introduction to literature, particularly in regard to the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and for the first time experienced a distance from his family life in a small-town Christian environment. During this period, the fatherless youth came under the influence of the once prominent poet Ernst Ortlepp, who—some modern biographers believe—probably felt attracted to the young Nietzsche.

After graduation, in 1864, Nietzsche commenced studies in theology and classical philology at the University of Bonn. For a short time he and Deussen became members of the Burschenschaft Frankonia. After one semester and to the anger of his mother, he stopped his studies in theology, and concentrated on philology, with Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl, whom he followed to the University of Leipzig the next year. There, he became close friends with fellow student Erwin Rohde. Nietzsche's first philological publications appeared soon after. In 1865, Nietzsche became acquainted with the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, and he read Friedrich Albert Lange's Geschichte des Materialismus in 1866. He found both of these encounters stimulating: they encouraged him to expand his horizons beyond philology and to continue his schooling. In 1867, Nietzsche committed to one year of voluntary service with the Prussian artillery division in Naumburg. However, a bad riding accident in March 1868 left him unfit for service. Consequently Nietzsche returned his attention to his studies, completing them and first meeting with Richard Wagner later that year.

Professor at Basel (1869- 1879)

Based on Ritschl's support, Nietzsche received an extraordinary offer to become professor of classical philology at the University of Basel before having completed his doctorate degree or certificate for teaching. During his philological work there he discovered that the ancient poetic meter related only to the length of syllables, different from the modern, accentuating meter. After moving to Basel, Nietzsche renounced his Prussian citizenship: for the rest of his life he remained officially stateless. Nevertheless, he served on the Prussian side during the Franco-Prussian War as a medical orderly. In his short time in the military he experienced much, and witnessed the traumatic effects of battle. He also contracted diphtheria and dysentery. On returning to Basel in 1870, Nietzsche observed the establishment of the German Empire and the following era of Otto von Bismarck as an outsider and with a degree of skepticism regarding its genuineness. At the University, he delivered his inaugural lecture, 'On Homer's Personality'. Also, Nietzsche met Franz Overbeck, a professor of theology, who remained his friend throughout his life. The historian Jacob Burckhardt, whose lectures Nietzsche frequently attended, became another very influential colleague.

Nietzsche had already met Richard Wagner in Leipzig in 1868, and (sometime later) Wagner's wife Cosima. Nietzsche admired both greatly, and during his time at Basel frequently visited Wagner's house in Tribschen. The Wagners brought Nietzsche into their closest circle, and enjoyed the attention he gave to the beginning of the Festival House in Bayreuth. In 1870, he gave Cosima Wagner the manuscript of 'The Genesis of the Tragic Idea' as a birthday gift. In 1872, Nietzsche published his first book, The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music. However, his classical philological colleagues, including Ritschl, expressed little enthusiasm for the work, in which Nietzsche forewent a precise philological method to employ a style of philosophical speculation. In a polemic, Philology of the Future, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff dampened the book's reception and increased its notoriety. In response, Rohde (by now a professor in Kiel) and Wagner came to Nietzsche's defense. Nietzsche remarked freely about the isolation he felt within the philological community and attempted unsuccessfully to attain a position in philosophy at Basel.

Between 1873 and 1876, Nietzsche published separately four long essays: David Strauss: the Confessor and the Writer, On the Use and Abuse of History for Life, Schopenhauer as Educator, and Richard Wagner in Bayreuth. (These four later appeared in a collected edition under the title, Untimely Meditations.) The four essays shared the orientation of a cultural critique, challenging the developing German culture along lines suggested by Schopenhauer and Wagner. Starting in 1873, Nietzsche also accumulated the notes later posthumously published as Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks. During this time, in the circle of the Wagners, Nietzsche met Malwida von Meysenbug and Hans von Bülow, and also began a friendship with Paul Rée, who after 1876 influenced him in dismissing the pessimism in his early writings. However, his disappointment with the Bayreuth Festival of 1876, where the banality of the shows and the baseness of the public repelled him, caused him to finally distance himself from Wagner.

With the publication of Human, All-Too-Human in 1878, a book of aphorisms on subjects ranging from metaphysics to morality and from religion to the sexes, Nietzsche's departure from the philosophy of Wagner and Schopenhauer became evident. Also, Nietzsche's friendship with Deussen and Rohde cooled. Nietzsche in this time attempted to find a wife—to no avail. In 1879, after a significant decline in health, Nietzsche had to resign his position at Basel. Since his childhood, various disruptive illnesses had plagued him—moments of shortsightedness practically to the degree of blindness, migraine headaches, and violent stomach attacks. A riding accident in 1868 and diseases in 1870 may have aggravated these persistent conditions, which continued to affect him through his years at Basel, forcing him to take longer and longer holidays until regular work became no longer practical.

Free philosopher (1879 - 1889)

Driven by his illness to find more compatible climates, Nietzsche traveled frequently, and lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria, near St. Moritz in Switzerland, and many winters in the Italian cities of Genoa, Rapallo, and Turin, and in the French city of Nice. He occasionally returned to Naumburg to visit his family, and especially during this time, he and his sister had repeated periods of conflict and reconciliation. He lived on his pension from Basel, but also received aid from friends. A past student of his, Peter Gast (born Heinrich Köselitz), became a sort of private secretary to Nietzsche. To the end of his life, Gast and Overbeck remained consistently faithful friends. Malwida von Meysenbug remained like a motherly patron even outside the Wagner circle. Soon Nietzsche made contact with the music critic Carl Fuchs. Nietzsche stood at the beginning of his most productive period. Beginning with Human, All-Too-Human in 1878, Nietzsche would publish one book (or major section of a book) each year until 1888, his last year of writing, during which he completed five. In 1879, Nietzsche published Mixed Opinions and Maxims, which followed the aphoristic form of Human, All-Too-Human. The following year, he published The Wanderer and His Shadow. Both were published as the second part of Human, All-Too-Human with the second edition of the latter.

In 1881 Nietzsche published Daybreak: Reflections on Moral Prejudices, and in 1882 the first part of The Gay Science. That year he also met Lou Salomé through Malwida von Meysenbug and Paul Rée. Nietzsche and Salomé spent the summer together in Tautenburg, often with Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth as chaperone. However, Nietzsche regarded Salomé less as an equal partner than as a gifted student. He fell in love with her and pursued her despite their mutual friend Rée. When he asked to marry her, Salomé refused. Nietzsche's relationship with Rée and Salomé broke up in the winter of 1882-83, partially due to intrigues led by his sister Elisabeth. (Lou Salomé eventually came to correspond with Sigmund Freud, introducing him to Nietzsche's thought.) In the face of renewed fits of illness, in near isolation after a falling out with his mother and sister regarding Salomé, and plagued by suicidal thoughts, he fled to Rapallo, where in only ten days he wrote the first part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

After severing philosophical ties to Schopenhauer and social ties to Wagner, Nietzsche had few remaining friends. Now, with the new style of Zarathustra, his work became even more alienating and his readers received it only to the degree prescribed by politeness. Nietzsche recognized this and maintained his solitude, even though he often complained about it. He gave up his short-lived plan to become a poet in public, and was troubled by concerns about his publications. His books were as good as unsold. In 1885, he printed only 40 copies of the fourth part of Zarathustra, and only a fraction of these were distributed among close friends.

In 1886, he printed Beyond Good and Evil at his own expense. With this book and the appearance in 1886 - 1887 of second editions of his earlier works (The Birth of Tragedy, Human, All-Too-Human, Daybreak, and The Gay Science), he saw his work completed for the time and hoped that soon a readership would develop. In fact, the interest in Nietzsche did arise at this time, if also rather slowly and hardly perceived by him. During these years Nietzsche met Meta von Salis, Carl Spitteler, and also Gottfried Keller. In 1886, his sister Elisabeth married the anti-Semite Bernhard Förster and traveled to Paraguay to found a "Germanic" colony, a plan to which Nietzsche responded with laughter. Through correspondence, Nietzsche's relationship with Elisabeth continued on the path of conflict and reconciliation, but she would not see him again in person until after his collapse. He continued to have frequent and painful attacks of illness, which made prolonged work impossible. In 1887, Nietzsche quickly wrote the polemic On the Genealogy of Morals. He also exchanged letters with Hippolyte Taine, and then also with Georg Brandes, who at the beginning of 1888 delivered in Copenhagen the first lectures on Nietzsche's philosophy.

In the same year, Nietzsche wrote five books, based on his voluminous notes for the long-planned work, The Will to Power. His health seemed to improve, and he spent the summer in high spirits. In the fall of 1888 his writings and letters began to reveal an overestimation of his status and 'fate'. He overestimated the increasing response to his writings, above all, for the recent polemic, The Case of Wagner. On his 44th birthday, after completing The Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist, he decided to write the autobiography Ecce Homo, which presents itself to his readers in order that they 'ear me! For I am such and such a person. Above all, do not mistake me for someone else.' (Preface, sec. 1, tr. Walter Kaufmann) In December, Nietzsche began correspondence with August Strindberg, and thought that, short of an international breakthrough, he would attempt to buy back his older writings from the publisher and have them translated into other European languages. Moreover, he planned the publication of the compilation Nietzsche Contra Wagner and of the poems Dionysian Dithyrambs.

On 3 January 1889, Nietzsche had a mental collapse. That day two Turinese policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of Turin. What actually happened remains unknown. The often-repeated (and apocryphal) tale states that Nietzsche saw a horse being whipped at the other end of the Piazza Carlo Alberto, ran to the horse, threw his arms up around the horse’s neck to protect it, and collapsed to the ground. In the following few days, he sent short writings to a number of friends, including Cosima Wagner and Jacob Burckhardt, which showed signs of a breakdown. To his former colleague Burckhardt he wrote: 'I have had Caiphas put in fetters. Also, last year I was crucified by the German doctors in a very drawn-out manner. Wilhelm, Bismarck, and all anti-Semites abolished.' (The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann)

Mental breakdown and death (1889 - 1900)

On January 6 1889, Burckhardt showed the letter he received from Nietzsche to Overbeck. The following day Overbeck received a similarly revealing letter, and decided Nietzsche must be brought back to Basel. Overbeck traveled to Turin and brought Nietzsche to a psychiatric clinic in Basel. By that time, Nietzsche appeared fully in the grip of insanity, and his mother Franziska decided to bring him to a clinic in Jena under the direction of Otto Binswanger. From November 1889 to February 1890, Julius Langbehn attempted to cure Nietzsche, claiming that the doctors' methods were ineffective to cure Nietzsche's condition. Langbehn assumed greater and greater control of Nietzsche until his secrecy discredited him. In March 1890, Franziska removed Nietzsche from the clinic, and in May 1890 to her home in Naumburg.During this process, Overbeck and Gast contemplated what to do with Nietzsche's unpublished works. In January 1889 they proceeded with the planned release of The Twilight of the Idols, by that time already printed and bound. In February, they ordered a 50-copy private edition of Nietzsche Contra Wagner, but the publisher C. G. Naumann secretly printed 100. Overbeck and Gast decided to withhold publishing Der Antichrist and Ecce Homo due to their more radical content. Nietzsche's reception and recognition enjoyed their first surge. In 1893, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth returned from Paraguay after the suicide of her husband. She read and studied Nietzsche's works, and piece by piece took control of them and of their publication. Overbeck was eventually dismissed, and Gast finally co-operated. After the death of Franziska in 1897 Nietzsche lived in Weimar, where Elisabeth cared for him and allowed people to visit her uncommunicative brother.

Speculation continues as to the cause of Nietzsche's breakdown. Commentators early and frequently diagnosed a syphilitic infection; however, some of Nietzsche's symptoms seem inconsistent with typical cases of syphilis. Some have diagnosed a form of brain cancer. Others suggest that Nietzsche experienced a mystical awakening, similar to ones studied by Meher Baba. While most commentators regard Nietzsche's breakdown as unrelated to his philosophy, some, including Georges Bataille and René Girard, argue that his breakdown must be considered as symptom of a psychological maladjustment brought on by his philosophy.

On August 25 1900 Nietzsche died after contracting pneumonia. At the wish of Elisabeth, he was buried beside his father at the church in Röcken. His friend, Gast, gave his funeral oration, proclaiming: "Holy be your name to all future generations!" (Note that Nietzsche had pointed out in Ecce Homo how he did not wish to be called "holy".)

The Will to Power was a posthumously published work compiled by Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche from notes he had written. She had married an anti-Semitic agitator, and her brother had opposed her marriage from the beginning because he did not share her husband's anti-Semitic views. Since his sister arranged the book, the general consensus holds that it does not reflect Nietzsche's intent. Indeed, Mazzino Montinari, the editor of Nietzsche's Nachlass, called it a forgery. It has been the source of accusations that Nietzsche shared views similar to those of the Nazis.

Key concepts

Prominent Nietzsche translator Walter Kaufmann expressed, in his preface to The Portable Nietzsche, that, although Nietzsche's ideas may often seem contradictory, a thorough understanding of Nietzsche's free-thinking nature may also yield an explanation of these paradoxes. In addition to this, perspectivism intimates a thesis regarding the seeming contradictions in Nietzsche's writings, suggesting that Nietzsche used multiple viewpoints in his work as a means of challenging his reader to consider various facets of an issue. If one accepts this thesis, the variety and number of perspectives serve as an affirmation of the richness of philosophy. The thesis does, however, not claim that Nietzsche himself regarded all ideas as equally valid. Nietzsche's disagreements with many other philosophers, such as Kant, Plato, and Spinoza, populate his texts. Whether one holds conflicting elements in his writings as intentional or not, his various ideas continue to have influence:

Nihilism and the death of God

Nietzsche saw nihilism as the outcome of repeated frustrations in the search for meaning. He diagnosed nihilism as a latent presence within the very foundations of European culture, and saw it as a necessary and approaching destiny. The religious worldview had already suffered a number of challenges from contrary perspectives grounded in philosophical skepticism, and in modern science's evolutionary and heliocentric theory. Nietzsche saw this intellectual condition as a new challenge to European culture, which had extended itself beyond a sort of point-of-no-return. Nietzsche conceptualizes this with the famous statement, 'God is dead', which is first seen in the beginning of Book III of The Gay Science (section 108), again prominently in section 125, and even more famously in his Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The statement adresses the impending crisis that Western culture faced in the wake of the irreparable disturbances to its traditional foundations (i.e, with the rise of nihilism). Nietzsche treats this phrase reverently, as more than a provocative declaration:

The greatest recent event—that “God is dead,” that the belief in the Christian god has become unbelievable—is already beginning to cast its first shadows over Europe. For the few at least, whose eyes—the suspicion in whose eyes is strong and subtle enough for this spectacle, some sun seems to have set and some ancient and profound trust has been turned into doubt; to them our old world must appear daily more like evening, more mistrustful, stranger, “older.” But in the main one may say: The event itself is far too great, too distant, too remote from the multitude's capacity for comprehension even for the tidings of it to be thought of as having arrived as yet. Much less may one suppose that many people know as yet what this event really means—and how much must collapse now that this faith has been undermined because it was built upon this faith, propped up by it, grown into it; for example, the whole of our European morality. This long plenitude and sequence of breakdown, destruction, ruin, and cataclysm that is now impending—who could guess enough of it today to be compelled to play the teacher and advance proclaimer of this monstrous logic of terror, the prophet of a gloom and an eclipse of the sun whose like has probably never yet occurred on earth?

— Nietzsche, Gay Science, Book V, sec. 343, trans. Walter Kaufmann

Amor fati and the eternal recurrence

Nietzsche encountered the idea in the works of Heinrich Heine, who speculated that there would one day be a person born with the same thought processes as himself, and that the same was true of every other person on the planet. Nietzsche expanded on this thought to form his theory, which he put forth in The Gay Science and developed in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In Nietzsche's reading of Schopenhauer, he came across the idea of eternal recurrence. Schopenhauer claimed that a person who unconditionally affirms life would do so even if everything that has happened were to happen again repeatedly. On a few occasions in his notebooks, Nietzsche discusses the possibility of the Eternal Recurrence as cosmological truth (see Arthur Danto, Nietzsche as Philosopher for a detailed analysis of these efforts), but in the works he prepared for publication, it is treated as the ultimate method of life affirmation. According to Nietzsche, it would require a sincere Amor Fati (Love of Fate), not simply to endure, but to wish for the eternal recurrence of all events exactly as they occurred---all of the pain and joy, the embarrassment and glory. Nietzsche calls the idea "horrifying and paralyzing", and he also characterises the burden of this idea as the "heaviest weight" imaginable (das schwerste Gewicht). The wish for the eternal return of all events would mark the ultimate affirmation of life:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.'

— Nietzsche, The Gay Science

According to a few interpreters, the eternal return is more than merely an intellectual concept or challenge, it resembles a koan, or a psychological device that occupies one's entire consciousness stimulating a transformation of consciousness known as metanoia.

Nehamas wrote in Nietzsche: Life as Literature that there are three ways of seeing the eternal recurrence. "(A) My life will recur in exactly identical fashion." This is a totally fatalistic approach to the idea. "(B) My life may recur in exactly identical fashion." This second view is a conditional assertion of cosmology, but fails to capture what Nietzsche refers to in GS, 341. Finally, "(C) If my life were to recur, then it could recur only in identical fashion." Nehemas shows that this interpretation is totally independent of physics and does not presuppose the truth of cosmology. Nehamas' interpretation is that if individuals constitute themselves through their actions the only way to maintain themselves as they are is to live in a reoccurrence of past actions (Nehamas 153).

Overman

Main article: ÜbermenschSome controversy exists over who or what Nietzsche considered the overman (in German, Übermensch). Not only is there some basis to think that Nietzsche was skeptical about individual identity and the notion of the subject, but whether there was a concrete example of the overman remains unclear. The interpretation of Nietzsche as the "Nazi Philosopher" has come to suggest the overman as a Hitler or even Mussolini but modern interpretations of Nietzsche, especially after the work of Walter Kaufmann, suggest that Nietzsche's vision of the overman is more in line with the concept of a Renaissance type of man, similar to such creative figures as Goethe or Da Vinci.

Master morality and slave morality

Main article: Master-Slave MoralityNietzsche argued that there were two types of morality, a master morality that springs actively from the 'noble man' and a slave morality that develops reactively within the weak man. These two moralities are not simple inversions of one another, they are two different value systems; master morality fits actions into a scale of 'good' or 'bad' whereas slave morality fits actions into a scale of 'good' or 'evil'.

Christianity as an institution and Jesus

In his book the Anti-Christ, Nietzsche fights against how Christianity has become an ideology set forth by institutions like churches, and how churches have failed to represent the life of Jesus. It is important, for Nietzsche, to distinguish between the religion of Christianity and the person of Jesus. Nietzsche attacked Christian religion as it was represented by churches and institutions for what he called its "transvaluation" of healthy instinctive values. Transvaluation is the process by which the meaning of a concept or ideology can be viewed from a "higher" context. He went beyond agnostic and atheistic thinkers of the Enlightenment, who felt that Christianity was simply untrue. He claimed that it may have been deliberately propagated as a subversive religion (a "psychological warfare weapon") within the Roman Empire by the Apostle Paul as a form of covert revenge for the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple during the Jewish War. Nietzsche contrasts the Christians with Jesus, whom he regarded as a unique individual, and argues he established his own moral evaluations. As such, Jesus represents a kind of step towards his ideation of the overman. Ultimately, however, Nietzsche claims that, unlike the overman, who embraces life, Jesus denied reality in favor of his "kingdom of God." Jesus's refusal to defend himself, and subsequent death, were logical consequences of this total disengagement. Nietzsche goes further to analyze the history of Christianity, finding it to be a progressively grosser distortion of the teachings of Jesus. He criticizes the early Christians for turning Jesus into a martyr and Jesus's life into the story of the redemption of mankind in order to dominate the masses and finds the Apostles to be cowardly, vulgar, and resentful. He argues that successive generations further misunderstood the life of Jesus, as the influence of Christianity grew. By the 19th century, Nietzsche concludes, Christianity had become so worldly as to be a parody of itself—a total inversion of a worldview which was, in the beginning, nihilistic, thus implying the "death of God".

Place in contemporary ethical theory

Nietzsche's work addresses ethics from several perspectives: meta-ethics, normative ethics, and descriptive ethics.

As far as meta-ethics is concerned, Nietzsche can perhaps most usefully be classified as a moral skeptic; that is, he claims that all ethical statements are false, because any kind of correspondence between ethical statements and "moral facts" is illusory. (This is part of a more general claim that there is no universally true fact, roughly because none of them more than "appear" to correspond to reality). Instead, ethical statements (like all statements) are mere "interpretations."

Sometimes, Nietzsche may seem to have very definite opinions on what is moral or immoral. Note, however, that Nietzsche's moral opinions may be explained without attributing to him the claim that they are "true". For Nietzsche, after all, we needn't disregard a statement merely because it is false. On the contrary, he often claims that falsehood is essential for "life." Interestingly enough, he mentions a 'dishonest lie,' discussing Wagner in The Case of Wagner, as opposed to an 'honest' one, saying further, to consult Plato with regards to the latter, which should give some idea of the layers of paradox in his work.

In the juncture between normative ethics and descriptive ethics, Nietzsche distinguishes between "master morality" and "slave morality." Although he recognises that not everyone holds either scheme in a clearly delineated fashion without some syncretism, he presents them in contrast to one another. Some of the contrasts in master vs. slave morality:

- "good" and "bad" interpretations vs. "good" and "evil" interpretations

- "aristocratic" vs. "part of the 'herd'"

- determines values independently of predetermined foundations (nature) vs. determines values on predetermined, unquestioned foundations (Christianity).

These ideas were elaborated in his book On the Genealogy of Morals in which he also introduced the key concept of ressentiment as the basis for the slave morality.

The revolt of the slave in morals begins in the very principle of ressentiment becoming creative and giving birth to values — a ressentiment experienced by creatures who, deprived as they are of the proper outlet of action are forced to find their compensation in an imaginary revenge. While every aristocratic morality springs from a triumphant affirmation of its own demands, the slave morality says 'no' from the very outset to what is 'outside itself,' 'different from itself,' and 'not itself'; and this 'no' is its creative deed.

— Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals

Nietzsche's primarily negative assessment of the ethical and moralistic teachings of the world's monotheistic religions followed from his earlier considerations of the questions of God and morality in the works The Gay Science and Thus Spoke Zarathustra. These considerations led Nietzsche to the idea of eternal recurrence and to the (in)famous phrase God is Dead. Nietzsche primarily meant that, for all practical purposes, his contemporaries lived as if God were dead, though they had not yet recognized it. Nietzsche believed this "death" had already started to undermine the foundations of morality and would lead to moral relativism and moral nihilism. As a response to the dangers of these trends he believed in re-evaluating the foundations of morality to better understand the origins and motives underlying them, so that individuals might decide for themselves whether to regard a moral value as born of an outdated or misguided cultural imposition or as something they wish to hold true.

Political views

While a political tone is easy to discern in Nietzsche's writings, his work does not in any sense propose or outline a 'political project'. The man who stated that 'The will to a system is a lack of integrity' was consistent in never devising or advocating a specific system of governance - just as, being an advocate of individual struggle and self-realization, he never concerned himself with mass movements or with the organization of groups and political parties. In this sense, Nietzsche could almost be called an anti-political thinker. Walter Kaufmann put forward the view that the powerful individualism expressed in his writings would be disastrous if introduced to the public realm of politics. Later writers, led by the French intellectual Left, have proposed ways of using Nietzschean theory in what has become known as the 'politics of difference' — particularly in formulating theories of political resistance and sexual and moral difference.

Owing largely to the writings of Kaufmann and others, the spectre of Nazism has now been almost entirely exorcised from his writings. Nietzsche often referred to the common people who participated in mass movements and shared a common mass psychology as "the rabble" or "the herd." He valued individualism above all else, and was particularly opposed to pity and altruism (one of the things that he seems to have detested the most about Christianity was its emphasis on pity and how this allegedly leads to the elevation of the weak-minded). While he had a dislike of the state in general, Nietzsche also spoke negatively of anarchists and made it clear that only certain individuals could attempt to break away from the herd mentality. This theme is common throughout Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It was also long thought that one central political theme running through much of Nietzsche's work was Social Darwinism ---- the idea that the strong have a natural right to dominate the weak, and that feelings such as compassion and mercy are burdens to be overcome. This, too, is based on a misrepresentation of his critiques of morality and politics: the 'genealogical method' is, in this sense, an appeal to the possibility of different moral values rather than a defence per se of what he describes as 'master-' or 'slave morality'. This has influenced a great variety of political movements in the century that has elapsed since Nietzsche's death, and, because all those movements claim Nietzsche as part of their intellectual legacy, it is often difficult to distinguish Nietzsche's own views from the views of those who claim to follow him.

Perhaps Nietzsche's greatest political legacy lies in his 20th century interpreters, among them Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze (and Félix Guattari), and Jacques Derrida. Foucault's later writings, for example, adopt Nietzsche's genealogical method to develop anti-foundationalist theories of power that divide and fragment rather than unite polities (as evinced in the liberal tradition of political theory). The systematic institutionalisation of criminal delinquency, sexual identity and practice, and the mentally ill (to name but a few) are examples used to demonstrate how knowledge or truth is inseparable from the state institutions that formulate notions of legitimacy from 'immoralities' such as homosexuality and the like (captured in the famous power/knowledge equation). Deleuze, arguably the foremost of Nietzsche's interpreters, used the much-maligned 'will to power' thesis in tandem with Marxian notions of commodity surplus and Freudian ideas of desire to articulate concepts such the rhizome and other 'outsides' to state power as traditionally conceived.

Views on women

Noted as a Nietzsche scholar and translator, Walter Kaufmann has gone so far as to call Nietzsche's remarks on women "second-rate". That Nietzsche also mocked men and manliness has not saved him from the charge of sexism. However, the women he associated with typically reported that he was more amiable and respectful than most educated men of the time. Much of Nietzsche's commentary on women (and men) should be read in light of his re-evaluation of morality and his desire for humanity to evolve and overcome the limitations of the individual. E.g., why push for women's involvement in politics when women can direct their energies toward something "more"? Moreover, some of his statements on women seem to prefigure the criticisms of post-feminism against prior versions of feminisms, particularly those that claim orthodox feminism does violence to women by positing and privileging the ideation of woman. In this connection to Nietzsche's commentaries, he was acquainted with Schopenhauer's work "On Women" and was probably influenced by it to some degree. As it would at first appear, some statements scattered throughout his works seem to attack women in a similar vein.

Nietzsche's view of women is based upon their role as potential mothers, and he places the creation of greater things as the central task of a rich and valuable life; it is an exultation of womanhood as maternity. This, and the distinction between the sexes as seen by Nietzsche emerges in the following aphorism:

When a woman has scholarly inclinations there is generally something wrong with her sexually. Sterility itself disposes one toward a certain masculinity of taste; for man is, if I may say so, “the barren animal.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche; trans. Walter Kaufmann, Beyond Good and Evil, sec. 144 (Epigrams and Interludes)'

This stands in contrast to the then (and still) prevailing view of Woman as the receptacle of male fertility (exemplified by Sigmund Freud's views on women). Nietzsche states here a continuation of his anti-nihilism and his belief that fruitfulness is meaning--because man has no natural avenue for a meaningful existence he sets himself into fruitful pursuits. Woman, however, is herself a source of fertility. That is to say, both are capable of doing their share of humanity's work, with their respective physiological conditions.

However, Nietzsche lacks clarity in expressing whether this image of woman is a product of nature or of nurture: While he sometimes suggests the former, he only explicitly discusses the attitudes, tendencies and values that are the latter. It may be misleading to generalise from Nietzsche's writings--he was not a systemic philosopher. The implication exists that woman can take a different path than the one he has laid out, even if it contradicts her 'nature'. Nietzsche certainly never reprimanded any woman for taking a non-maternal role—-in final reading he is not even a proscriptive philosopher, since his emphasis on the transvaluation of all values would not allow it. Peter J. Burgard's Nietzsche and the Feminine and Frances Nesbitt Oppel's Nietzsche on Gender: Beyond Man and Woman both read Nietzsche's statements on women as being yet another series of word-games amongst word-games, meant to challenge the reader and incite inspection of the concepts involved. French post-structural theorist Jacques Derrida made a similar argument in his Spurs. The following quotation on 'woman' (in reference to the German word for "truth", which has a feminine grammatical gender in German) also indicates this:

Supposing truth is a woman—what then? Are there not grounds for the suspicion that all philosophers, insofar as they were dogmatists, have been very inexpert about women? That the gruesome seriousness, the clumsy obtrusiveness with which they have usually approached truth so far have been awkward and very improper methods for winning a woman's heart? What is certain is that she has not allowed herself to be won—and today every kind of dogmatism is left standing dispirited and discouraged. If it is left standing at all!

— Friedrich Nietzsche; trans. Walter Kaufmann, Beyond Good and Evil, Preface'

Nietzsche's influence and reception

Nietzsche became popular among left-wing Germans in the 1890s, but a few decades later, during the First World War, many regarded him as one of the sources of right-wing German militarism. The Dreyfus Affair provides another example: the French anti-semitic Right labelled Jewish and Leftist intellectuals who defended Alfred Dreyfus as Nietzscheans. In 1894/1895 German conservatives wanted to ban Nietzsche's work, accusing it of subversion; while Nazi Germany used a highly selective version of Nietzsche to promote Nazi ideas on a revival of traditional German culture and national identity. Many Germans read Thus Spoke Zarathustra and gained exposure to Nietzsche's appeals for unlimited individualism and for the development of a personality.

During the interbellum, Nazis appropriated various fragments of Nietzsche's work, notably Alfred Baeumler in his reading of The Will to Power. During the period of Nazi rule German (and, after 1938, Austrian) schools and universities studied Nietzsche's work widely. The Nazis viewed Nietzsche as one of their "founding fathers". They incorporated much of his ideology and many of his thoughts about power into their own political philosophy. Although there exist few, if any, resemblances between Nietzsche and Nazism (see political views above), phrases like "the will to power" became common in Nazi society.The wide popularity of Nietzsche among Nazis stemmed partly from Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, a Nazi sympathizer who edited much of Nietzsche's works. However, Nietzsche disapproved of his sister's anti-Semitic views; in a letter to his sister, dated Christmas 1887, Nietzsche wrote:

You have committed one of the greatest stupidities – for yourself and for me! Your association with an anti-Semitic chief expresses a foreignness to my whole way of life which fills me again and again with ire or melancholy. … It is a matter of honour with me to be absolutely clean and unequivocal in relation to anti-Semitism, namely, opposed to it, as I am in my writings. I have recently been persecuted with letters and Anti-Semitic Correspondence Sheets. My disgust with this party (which would like the benefit of my name only too well) is as pronounced as possible.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Letter to His Sister, Christmas 1887

Furthermore, Mazzino Montinari, one of editors of Nietzsche's posthumous works in the 1960s, argued that Förster-Nietzsche had deliberately cut extracts, changed their order, and added false titles to the posthumous fragments, thus constituting the fake Will to power .

Since World War II Nietzsche has generally had more influence on the political left, particularly in France by way of post-structuralist thought (Gilles Deleuze and Pierre Klossowski wrote monographs to draw new attention to his work, and a 1972 conference at Cérisy-la-Salle ranks as the most important event in France for a generation's reception of Nietzsche). In his 1916 Egotism in German Philosophy, American philosopher George Santayana dismissed Nietzsche as a "prophet of Romanticism". The psychologist Carl Jung recognized Nietzsche's importance early on: he held a seminar on Nietzsche's Zarathustra in 1934. In 1936, Martin Heidegger lectured on the "Will to Power as a Work of Art", and would later publish four large volumes of lectures on Nietzsche. The German novelist Thomas Mann also showed Nietzsche's influence in his novels, especially his 1947 work Doktor Faustus.

In 1938, the German existentialist Karl Jaspers commented about the influence of Nietzsche:

The contemporary philosophical situation is determined by the fact that two philosophers, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, who did not count in their times and, for a long time, remained without influence in the history of philosophy, have continually grown in significance. Philosophers after Hegel have increasingly returned to face them, and they stand today unquestioned as the authentically great thinkers of their age. ... The effect of both is immeasurably great, even greater in general thinking than in technical philosophy ...

— Jaspers, Reason and Existenz

According to Ernest Jones, biographer and personal acquaintance of Sigmund Freud, Freud had frequently referred to Nietzsche as having "more penetrating knowledge of himself than any man who ever lived or was likely to live" (Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud). Nevertheless, Jones also reports that Freud emphatically denied that Nietzsche's writings influenced his psychological discoveries, since Freud had been uninterested in philosophic works as a medical student. He formed his opinion about Nietzsche later in life.

Nietzsche's appropriation by the Nazis, combined with the advent of analytic philosophy, insured that people in Great Britain and the United States almost completely ignored him until at least 1950. Analytic philosophers often charactized Nietzsche as a literary figure rather than as a philosopher. In 1950, the German-American philosopher Walter Kaufmann published Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, which, along with Kaufmann's accurate translations of Nietzsche's major works, began the gradual restoration among English-speaking philosophy departments of Nietzsche as an important nineteenth-century philosopher. Kaufmann was a strong advocate of Nietzsche, but even he had some criticism: "It is evident at once that Nietzsche is far superior to Kant and Hegel as a stylist; but it also seems that as a philosopher he represents a very sharp decline." (p 79)

Recognition of Nietzsche's contribution to literature continued substantially in the later 20th century, especially among French post-structuralist thinkers. Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Michel Foucault all owe a heavy debt to Nietzsche. Others influenced by Nietzsche include "Death of God" theologian Thomas Altizer, Jim Morrison, and novelists Nikos Kazantzakis, Mikhail Artsybashev, and Lu Xun. Literary critic Harold Bloom's theory of the "anxiety of influence" shows Nietzschean influence. Bloom calls Nietzsche "Emerson's belated rival".

Works

For a complete bibliography, see List of works by Friedrich Nietzsche

References

- Nietzsche by Richard Schacht (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983).

- Reading the New Nietzsche by David B. Allison (Rowman & Littlefield, 2001).

- Nietzsche: Life as Literature by Alexander Nehamas (Harvard University Press, 1985, ISBN 0674624351)

- Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist by Walter Kaufmann (Princeton University Press, 1974, ISBN 0691019835).

- Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy by Maudemarie Clark (Cambirdge University Press, 1990).

- Nietzsche on Morality by Brian Leiter (Routledge, 2002).

- Nietzsche's System by John Richardson (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Nietzsche's Philosophy of Science by Babette E. Babich (State University of New York Press, 1994).

- Nietzsche Humanist by Claude Pavur (Marquette University Press, 1998, ISBN 0874626145)

- Kierkegaard and Nietzsche by J. Kellenberger (St. Martin's Press Inc, 1997).

- Nietzsche in German politics and society, 1890-1918 by Richard Hinton Thomas (Manchester University Press, 1983).

- Nietzsche: Volumes One and Two by Martin Heidegger (HarperSanFrancisco, Harper edition, 1991, ISBN 0060638419).

- Nietzsche: Volumes Three and Four by Martin Heidegger (HarperSanFrancisco, 1991, ISBN 0060637943)

- Nietzsche: A Critical Life. by Ronald Hayman (Oxford University Press, 1980, ISBN 019520204X).

- Friedrich Nietzsche. Biographie. by Curt Paul Janz (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1993, ISBN 3423043830).

- To Nietzsche: Dionysus, I Love You! Ariadne by Claudia Crawford (State University of New York Press, 1994, ISBN 0791421503).

- Notes and Discussions: Nietzsche's Knowledge of Kierkegaard by Thomas H. Brobjer. Journal of the History of Philosophy - Volume 41, Number 2, April 2003, pp. 251-263

- Reason and Existenz by Karl Jaspers (Marquette University Press, 1996, ISBN 0874626110).

- Nietzsche, Godfather of Fascism? : On the Uses and Abuses of a Philosophy, Jacob Golomb & Walter S. Wistrich (eds.) (Princeton U P, 2002, ISBN 0691007101).

- The Essential Nietzsche by Paul Strathern (Ted Smart, 1996, London).

External links

Full texts of Nietzsche's works:

- Works by Friedrich Nietzsche at Project Gutenberg

- The Antichrist (English translation by H. L. Mencken)

- Der Antichrist (German text)

- Wiki Nietzsche (French and German)

Other links:

- Open Directory Project: Friedrich Nietzsche

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Friedrich Nietzsche

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy

- Nietzsche Chronicle (Detailed Chronology and Biography)

- Nietzsche and the Pillars of Unbelief

- The Nietzsche Circle

- Friedrich Nietzsche Society

- Nietzsche and Ortlepp

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: