This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Cwmhiraeth (talk | contribs) at 18:42, 28 August 2013 (Completely rewritten article). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:42, 28 August 2013 by Cwmhiraeth (talk | contribs) (Completely rewritten article)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Birth (disambiguation).Birth is the act or process of bearing or bringing forth offspring from the uterus. In mammals, the process is initiated by hormones which cause the walls of the uterus to contract, expelling the foetus at a developmental stage where it can feed and breathe. In some species the offspring is precocial and can move around almost immediately after birth but in others it is altricial and completely dependent on its parent. In marsupials, the foetus is born at a very immature stage after a short gestational period and develops further in its mother's pouch.

It is not only mammals that give birth. Some reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates carry their developing young inside them. Some of these are ovoviviparous, with the eggs being hatched inside the mother's body, and others are vivparous, with the embryo developing inside her body, as in mammals. Both eventually lead to a live birth.

Human birth

Main article: Childbirth

The mother's body is prepared for birth by hormones produced by the pituitary gland, the ovary and the placenta. The total gestation period is about 266 days and the process of giving birth starts with a series of involuntary contractions of the uterus. These get stronger and increase in frequency and the head of the baby (unless it is a breech birth) is pushed against the cervix. The cervix gradually dilates, a process that may take many hours, especially in a women bearing her first child. The sac in which the baby is enclosed also helps in the dilatation process but at some stage, the sac bursts and the amniotic fluid escapes. When the cervix is fully relaxed, further strong contractions of the uterus push the baby out through the vagina and the baby is born. Further contractions expel the placenta, usually within a few minutes.

Birth in other mammals

Humans are unusual among mammals in producing a single offspring at one time. Other mammals that do this include other primates, horses, some antelopes, giraffes, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, elephants, seals. whales, dolphins and porpoises although all may have twins or multiple births on occasions. In these large animals, the birth process is similar to that of a human though in most, the offspring is precocial. This means that it is born in a more advanced state than a human baby and is able to stand, walk and run (or swim in the case of an aquatic mammal) shortly after birth. In the case of whales, dolphins and porpoises, the single calf is normally born tail first which minimises the risk of drowning. The mother encourages the newborn calf to rise to the surface to breathe.

The birth of a calf to a cow is typical of a larger mammal. The animal seeks a quiet place away from the rest of the herd. The contractions of the uterus are not obvious externally but the cow may be restless and keep getting up and lying down. She may stand with her tail slightly raised and her back arched. The first external sign of the imminent birth is the protrusion of the water bag from the vulva. This is followed by first one front foot and rather later by two, which may disappear from view between batches of contractions. By this time the head of the calf is being pushed against the cervix and the ligaments connecting the bones of the pelvis are relaxed. When the cervix has opened sufficiently, further contractions push the calf's head through and the nose, followed by the whole head can be seen projecting externally beside the forelegs. The rest of the birth is usually quite quick and the body of the calf slithers out, wrapped in the amniotic membranes. The cow scrambles to its feet (if lying down at this stage), turns round and starts vigorously licking the calf. The calf takes its first few breaths and within minutes is struggling to rise to its feet. The placenta is usually expelled within a few hours and is often eaten by the normally herbivorous cow. The calf noses under the cow's belly searching for a teat and is soon feeding on the colostrum produced by the mammary glands in the udder.

Most smaller mammals have multiple births, producing litters of young which may number twelve or more. In these, each foetus is surrounded by its own placenta and amniotic membranes which separate from the wall of the uterus during labour and work their way towards the vulva. In the dog, the arrival of the first puppy is preceded by a bulging dark-coloured sac appearing at the vulva. After further contractions, this bag is expelled with the puppy inside. The bitch breaks the membrane, chews at the umbilical cord and usually eats the afterbirth. She licks the puppy vigorously which stimulates it to breath and it is soon looking for a teat. Meanwhile the next puppy wrapped in its sac is on its way. Each sac contains enough oxygen for the puppy to survive for about six minutes after which time it is likely to die if not yet breathing.

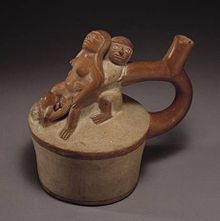

An infant marsupial is born in a very immature state. The gestation period is usually shorter than the intervals between oestrus periods. During gestation there is no placenta but the foetus is contained in a little yellow sac and feeds on a yolk. The first sign that a birth is imminent is the mother cleaning out her pouch. When it is born, the infant is pink, blind, furless and a few centimetres long. It has nostrils in order to breathe and forelegs to cling onto its mother's hairs but its hind legs are undeveloped. It crawls through its mother's fur and makes its way into the pouch. Here it fixes onto a teat which swells inside its mouth. It stays attached to the teat for several months until it is sufficiently developed to emerge.

Birth in other animals

The vast majority of invertebrates, most fish, reptiles and amphibians and all birds are oviparous, that is, they lay eggs with little or no embryonic development taking place within the mother. In aquatic organisms, fertilisation is nearly always external with sperm and eggs being liberated into the water. Millions of eggs may be produced with no further parental involvement, in the expectation that a small number may survive to become mature individuals. Terrestrial invertebrates may also produce large numbers of eggs, a few of which may avoid predation and carry on the species. Some fish, reptiles and amphibians have adopted a different strategy and invest their effort in producing a small number of young at a more advanced stage which are more likely to survive to adulthood. Birds care for their young in the nest and provide for their needs after hatching and it is perhaps unsurprising that internal development does not occur in birds, given their need to fly.

Ovoviviparity is a mode of reproduction in which embryos develop inside eggs that are retained within the mother's body until they are ready to hatch. Ovoviviparous animals are similar to viviparous species in that there is internal fertilization and the young are born in an advanced state, but differ in that there is no placental connection and the unborn young are nourished by egg yolk. The mother's body provides gas exchange (respiration), but that is largely necessary for oviparous animals as well. In many sharks the eggs hatch in the oviduct within the mother's body and the embryos are nourished by the egg's yolk and fluids secreted by glands in the walls of the oviduct. The Lamniforme sharks practice oophagy, where the first embryos to hatch consume the remaining eggs and sand tiger shark pups cannibalistically consume neighbouring embryos. The requiem sharks maintain a placental link to the developing young, this practice is known as viviparity. This is more analogous to mammalian gestation than to that of other fishes. In all these cases, the young are born alive and fully functional. The majority of caecilians are oviviviparous and give birth to already developed offspring. When the young have finished their yolk sacs they feed on nutrients secreted by cells lining the oviduct and even the cells themselves which they eat with specialist scraping teeth. The Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra) and several species of Tanzanian toad in the genus Nectophrynoides are oviviviparous, developing through the larval stage inside the mother's oviduct and eventually emerging as fully formed juveniles.

A more developed form of vivipary called placental viviparity is adopted by some species of scorpions and cockroaches, certain genera of sharks, snakes and velvet worms. In these, the developing embryo is nourished by some form of placental structure. Many species of skink are viviparous. Some are ovoviviparous but others such as members of the genera Tiliqua and Corucia, give birth to live young that develop internally, deriving their nourishment from a mammal-like placenta attached to the inside of the mother's uterus. In a recently described example, an African species, Trachylepis ivensi, has developed a purely reptilian placenta directly comparable in structure and function to a mammalian placenta.

References

- Birth, dictionary.com, Retrieved on June 10, 2010.

- ^ Dorit, R. L.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. pp. 526–527. ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- Mark Simmonds, Whales and Dolphins of the World, New Holland Publishers (2007), Ch. 1, p. 32 ISBN 1845378202.

- Crockett, Gary (2011). "Humpback Whale Calves". Humpback whales Australia. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- "Calving". Alberta: Agriculture and Rural Development. 2000-02-01. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- Dunn, T.J. "Whelping: New Puppies On The Way!". Puppy Center. Pet MD. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- "Reproduction and development". Thylacine Museum. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ^ Attenborough, David (1990). The Trials of Life. pp. 26–30. ISBN 9780002199124.

- "Birth and care of young". Animals: Sharks and rays. Busch Entertainment Corporation. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- Stebbins, Robert C.; Cohen, Nathan W. (1995). A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- Stebbins, Robert C.; Cohen, Nathan W. (1995). A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- Capinera, John L., Encyclopedia of entomology. Springer Reference, 2008, p. 3311.

- Costa, James T., The Other Insect Societies. Belknap Press, 2006, p. 151.

- Blackburn1, Daniel G.; Flemming, Alexander F. (2012). "Invasive implantation and intimate placental associations in a placentotrophic African lizard, Trachylepis ivensi (Scincidae)". Journal of Morphology. 273 (2): 137–159. doi:10.1002/jmor.11011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)