This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tonimicho (talk | contribs) at 10:50, 25 January 2014. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:50, 25 January 2014 by Tonimicho (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Todor Aleksandrov | |

|---|---|

| File:Alexandrov.jpgPortrait | |

| Born | (1881-03-04)March 4, 1881 Štip, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | August 31, 1924 Sugarevo, Bulgaria |

Todor Aleksandrov Poporushov also transliterated as Todor Alexandrov (Bulgarian:Тодор Александров) also spelt Alexandroff, (March 4, 1881 - August 31, 1924) was a Macedonian Bulgarian freedom fighter and member of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC) and later of the Central Committee of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO). In the Republic of Macedonia Todor Aleksandrov, who previously was dismissed as Bulgarophile, has been recently added to the country's historical heritage.

Biography

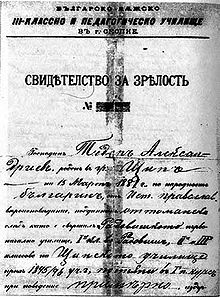

Aleksandrov was born in the Novo Selo suburb of Štip, present day Republic of Macedonia, to Aleksandar Poporushev and Marija Aleksandrova. In 1898, he finished the Bulgarian Pedagogical School in Skopje and became a Bulgarian teacher consecutively in the towns of Kocani, Kratovo, the village of Vinica, and Štip. He also attended the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki.

In 1903 Todor Aleksandrov distinguished himself as an extraordinary leader and organizer of the Kocani Revolutionary District. He was arrested by the Ottoman authorities on March 3, 1903 and sent to Skopje under enforced police escort during the same night. He was sentenced to five years of solitary confinement by the extraordinary court there. In April 1904, he was released after an amnesty. Soon afterwards, he was appointed a head teacher in the Second high-school in Štip. Aleksandrov, in co-operation with Todor Lazarov and Mishe Razvigorov, worked day and night to organize the Štip Revolutionary District. The results of his activities were detected by the Ottoman authorities and in November 1904 he was forbidden to teach. On January 10, 1905 Aleksandrov's house was surrounded by a numerous troops but he succeeded in breaking through the military cordoned and immediately joined the cheta (band) of Mishe Razvigorov where he became its secretary. Aleksandrov attended the First Congress of the Skopje Revolutionary Region as a delegate from the Štip district.

His deteriorating health lead him to become a teacher in Bulgaria — the Black Sea town of Burgas in 1906, but after learning about the death of Mishe Razvigorov, he abandoned his work as a teacher and returned to Macedonia at once. In November 1907, Aleksandrov was elected as a district vojvoda (commander) by the Third Congress of the Skopje Revolutionary District.

On August 2, 1909 the Ottomans made another attempt to arrest him but failed again. In the spring of 1910 he and his cheta traversed the Skopje region and organized the revolutionary activities. At the beginning of 1911, Todor Aleksandrov became a member of the Central Committee of the IMARO. In 1912, he became a vojvoda in the Kilkis and Thessaloniki districts where he carried out a number of sabotages against Ottoman targets, facilitating this way the Bulgarian cause in the First Balkan War. He supported the Bulgarian army. In 1913, he was at the head quarters of the Third brigade of the Macedonian Militia in the Bulgarian army. After 1913 he organized the IMARO resistance against other nationalities - Serbs and Greeks. On November 4, 1919 Aleksandrov was arrested by the government of Aleksandar Stamboliyski but he succeeded to escape nine days later. In the spring of 1920, Aleksandrov went with a cheta to Serbian Macedonia where he restored the revolutionary organization and attracted the world's attention to the unsolved Macedonian question. At the end of 1922, there was a bounty of 250,000 denars placed on him by the Serbian authorities in Belgrade.

In 1924 IMRO entered negotiations with the Comintern about collaboration between the communists and the creation of a united Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union, which saw a chance for using this well developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans and destabilize the Balkan monarchies. Alexandrov defended IMRO's independence and refused to concede on practically all points requested by the Communists. No agreement was reached besides a paper "Manifesto" (the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924), in which the objectives of the unified Macedonian liberation movement were presented: independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation and cooperation with the Soviet Union. Failing to secure Alexandrov's cooperation, the Comintern decided to discredit him and published the contents of the Manifesto on 28 July 1924 in the "Balkan Federation" newspaper. Todor Aleksandrov and Aleksandar Protogerov promptly denied through the Bulgarian press that they have ever signed any agreements, claiming that the May Manifesto was a communist forgery. Shortly after, Alexandrov was assassinated in unclear circumstances, when a member in his cheta shot him on August 31, 1924 in the Pirin Mountains. He was survived by a wife (Vangelia), son (Alexander) and daughter (Maria). Maria Aleksandrova (Koeva) was a strong proponent of her father's ideals and IMRO's charter.

View about the Macedonian Question

IMRO and Alexandrov himself aimed at an autonomous Macedonia, with its capital at Salonika and prevailing Macedonian Bulgarian element. He dreamed about transforming the Balkans into a federation through reconstruction of Yugoslavia into a federal state, in which Macedonia would enter as a member on equal rights with the other members. He took also into consideration the decomposition of Greece and the incorporation into the autonomous Macedonia of the Macedonian territory which was under the Greek dominion. The part of Macedonia which was in Bulgaria must also be incorporated into the autonomous Macedonia. His view does not indicate any doubt about the Bulgarian ethnic character of Macedonian Bulgarians then.

Monuments' controversies in the Republicof Macedonia

2008 monument controversy

A local association of Bulgarians in the Republic of Macedonia raised a monument of the revolutionary on February 2, 2008 in the city of Veles. After the local administration refused to provide a place for the bust it was raised in the yard of the local Bulgarian resident Dragi Karov. The following night Karov received a number of threats and the monument was twice thrown down by unknown individuals. Soon after, the monument was removed at the insistence of the local authorities, as an unlawful construction. This incident caused Bulgarian president Georgi Parvanov to call upon Republic of Macedonia to review the history of Alexandrov's deeds on his meeting with Branko Crvenkovski in the town of Sandanski.

2012 monument controversy

In June 2012, a new statue called “Macedonian Equestrian Revolutionary” was raised in Skopje. As a consequense an outcry among older of residents erupted almost immediately when they noted the anonymous rider’s similarity to the historical figure. The statue was reportedly commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, but even this was in question. The Ministry called the statue “the complete responsibility of the municipality of Kisela Voda (a part of greater Skopje).” The city government denied this. Attempts to reach a spokesperson at the Ministry of Culture for comment have thus been unsuccessful. Earlier the same month the opposition Social Democrats took to the streets to protest the changing of hundreds of street names, including a bridge that was to be named after Aleksandrov. Finally in October, a few months after the setting of the monument, on it appeared an board with the name of Todor Alexandrov.

Memorials

-

Monument of Alexandrov in Kyustendil, Bulgaria.

Monument of Alexandrov in Kyustendil, Bulgaria.

-

Monument of Alexandrov in Burgas, Bulgaria.

-

Monument of Alexandrov in Veles, Macedonia, demounted in 2008.

-

Bust of Todor Aleksandrov in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Bust of Todor Aleksandrov in Sofia, Bulgaria.

See also

- Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

- History of the Republic of Macedonia

- History of Bulgaria

References and notes

- "Уште робуваме на старите поделби", Разговор со д-р Зоран Тодоровски, директор на Државниот архив на Република Македониja (in Macedonian; in English: "We are still in servitude to the old divisions", interview with PhD Zoran Todorovski, Director of the State Archive of the Republic of Macedonia, published on , 27. 06. 2005. Трибуна: Дел од јавноста и некои Ваши колеги историчари Ве обвинуваат дека промовирате зборник за човек (Тодор Александров) кој се чувствувал како Бугарин. Кој наш револуционерен деец му противречел на Александров по тоа прашање? Тодоровски - Речиси никој. Уште робуваме на поделбата на леви и десни. Во етничка, во национална смисла сите биле со исти сознанија, со иста свест. In English: Tribune: Part of the public and some from your fellow historians accuse you of promotining a collection for man (Todor Alexandrov) who felt himself as Bulgarian. Are there some of our revolutionary activist who opposed him on that issue? Todorovski - Almost none. We are still in servitude to the old divisions of left and right. Ethnically, in a national sense, they were all with the same sentiments, with the same (Bulgarian) consciousness.

- Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Victor Roudometof, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 99.

- Crown of Thorns: The Reign of King Boris III of Bulgaria, 1918-1943, Stephane Groueff, Rowman & Littlefield, 1998, ISBN 1568331142,p. 118.

- Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 78.

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 140.

- The Times, (London), September 16, 1924, p. 9.

- …Мога да кажа пред безпристрастен арбитър, че никога не сме били и сега не сме оръдия на българските правителства и всякога сме били и трябва да бъдем "оръдия" на Независима България, на Българска Македония и на цялото българско племе…; в-к Македония, бр.№ 865, 31. 08. 1929, с. 5.

- ЦДА, ф. 1933, оп.2, а. е. 28, л. 68-73; Гергинов, Кр. Билярски, Ц. Непубликувани документи за дейността на ВМОРО, с. 214.; Непубликувани документи за дейността на ВМОРО, с. 205; Из архивното наследство…, с.231, 234, 237, 243, 247; Марков, Г. Камбаните бият сами…, с. 18-19.

- Sociétés politiques comparées 25 Mai, 2010; Tchavdar Marinov, Université de Sofia ‘St. Kliment Ohridski’; New Bulgarian University - Historiographical revisionism and rearticulation of memory in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, p.3, note #5.

- 28 Jun. 2012, Sinisa Jakov Marusic, Nameless Statue Causes Stir in Macedonia Balkan Insight.

- "News.bg — ВМРО откри паметник на Тодор Александров в Македония". news.ibox.bg. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- "News.bg — Македония и България са с обща история, обяви Първанов". news.ibox.bg. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- Hero or villain? New Skopje statue sparks controversy by Martin Laine, Digital Journal, Jun 29, 2012.

- Утрински вестик, 18.10.2012, „Војводата на коњ“ и официјално Тодор Александров.

External links

Categories:- 1881 births

- 1924 deaths

- People from Štip

- Members of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

- Bulgarian military personnel of World War I

- Bulgarian revolutionaries

- Macedonia under the Ottoman Empire

- Prisoners and detainees of the Ottoman Empire

- Bulgarian people imprisoned abroad

- Bulgarian people of the Balkan Wars

- Bulgarian Orthodox Christians

- Assassinated Bulgarian people

- Bulgarian educators

- Recipients of the Order of Military Merit (Bulgaria)

- Recipients of the Iron Cross, 2nd class

- Macedonian Bulgarians

- Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki alumni